Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a ubiquitous bacterium capable of twitching, swimming, and swarming motility. In this study, we present evidence that P. aeruginosa has two flagellar stators, conserved in all pseudomonads as well as some other gram-negative bacteria. Either stator is sufficient for swimming, but both are necessary for swarming motility under most of the conditions tested, suggesting that these two stators may have different roles in these two types of motility.

The opportunistic human pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a gram-negative rod that lives in a variety of soil and aqueous environments. This bacterium is capable of three different types of motility mediated by either its polar monotrichous flagellum or type IV pili (TFP) (for a review, see reference 19). Twitching motility is thought to be the result of the extension and retraction of the pilus filament, which propels the cell along a solid surface (22, 23, 41). P. aeruginosa is also able to swim in aqueous environments, propelled by its polar flagellum. In a semisolid environment (e.g., a hydrated gel or mucus), the cells are believed to switch from swimming to swarming motility (16, 20, 22). Swarming motility requires the flagellum as well as the production of rhamnolipid surfactants, which are thought to reduce friction between the cell and the surface over which it moves (31, 45). In contrast to other swarming organisms, there is no evidence that P. aeruginosa changes cell morphology and produces lateral flagella when swarming (31, 45).

The bacterial flagellum is powered by a transmembrane proton gradient (3, 36), or in some cases by a sodium ion gradient (24). The flagellar motor, studied extensively in the closely related enteric organisms Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, is responsible for translating the energy of the ion gradient into the physical rotation of the flagellum (33, 49, 50, 52). In E. coli, the flagellar motor can be divided in two substructures. The rotor is composed of the FliG, FliM, and FliN proteins and acts as a switch, determining the clockwise or counterclockwise rotation of the flagellum (15, 29). The second structure is the stator (the stationary component of the motor within which the rotor turns), which is composed of two integral membrane proteins, MotA and MotB, which form a complex with a ratio of four MotA to two MotB proteins (7, 32). Strains lacking MotA and/or MotB are capable of making a flagellum, but this organelle is unable to rotate (10, 12, 13). MotA has four transmembrane domains, whereas MotB has one transmembrane domain as well as a peptidoglycan-binding motif at its C terminus (9-11, 51). The MotAB complex is believed to conduct protons across the inner membrane and couples this proton transport to rotation of the motor (3, 33). Several stator complexes are associated with each motor, and each complex apparently can act independently to generate torque (4, 6).

Previously, Kato and colleagues reported that deletion of both PA1460 and PA1461, annotated as motA and motB, respectively, in the P. aeruginosa PA01 genome (47), resulted in no loss of swimming motility (28). Studies in P. aeruginosa 4020, a clinical isolate from a cystic fibrosis patient, identified the rpmA locus, named because it was identified as required for phagocytosis by macrophages (46). Simpson and Speert showed that the mutation in rpmA mapped to one of two putative copies of a motA homologue (PA4954); however, this mutation also had no effect on swimming motility (46). These data indicated that the role of the stator(s) in P. aeruginosa might be complicated and differ from that previously reported for E. coli (32).

Identification and sequence analysis of two putative flagellar stators in P. aeruginosa.

Little is known about the functioning of the flagellum in P. aeruginosa, despite its importance in pathogenesis and biofilm formation (26, 38, 43). The organization of the flagellar biosynthetic genes in E. coli and P. aeruginosa is very similar (5, 47), but analysis of the P. aeruginosa genome revealed two sets of genes with the potential to code for flagellar stators. The published genome of P. aeruginosa PA01 (www.pseudomonas.com) includes annotations for the predicted homologues of the E. coli motA and motB genes, designated PA4954 and PA4953, respectively. Interestingly, the P. aeruginosa PA4954 and PA4953 open reading frames are not in the same chromosomal context as the E. coli motAB genes, which are found adjacent to genes coding for the chemotaxis system in E. coli. A BLAST search (1) with the PA4954 and PA4953 sequences against the P. aeruginosa PA01 genome identified putative homologues of these two genes, PA1460 and PA1461, respectively. At the amino acid level, the PA4954 protein shares 24% identity and 43% similarity with PA1460 (Fig. 1A) and the PA4953 protein shares 26% identity and 39% similarity with PA1461 (Fig. 1B). The PA1460 and PA1461 open reading frames are located within a large cluster of che genes designated cluster I (PA1457 to -1465) (14, 27, 28, 37), with sequence similarity to chemotaxis genes of E. coli (5). A BLAST search of the genome of P. aeruginosa strain PA14 (GenBank accession numbers NZ_AABQ07000001 to NZ_AABQ07000005) showed that this strain also has two sets of genes with sequence similarity to MotAB, and their protein sequences as well as chromosomal organization are identical to P. aeruginosa PA01.

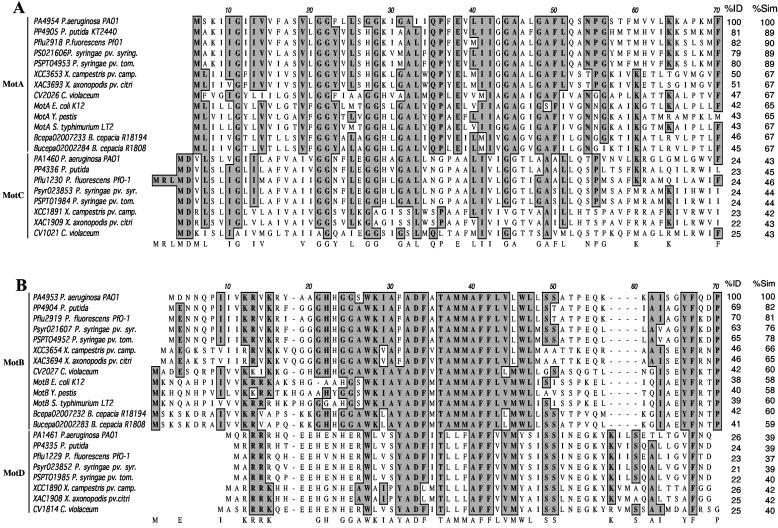

FIG. 1.

Protein sequence alignments of putative MotAB and MotCD stators. The bacterial species presented in these alignments are, in order, P. aeruginosa, Pseudomonas putida, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae, Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato, Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris, Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri, C. violaceum, E. coli, Y. pestis, S. enterica serovar Typhimurium, and B. cepacia strains R18194 and R1808. The proteins are identified by their locus tag or name. The percent identity (%ID) and percent similarity (%Sim) across the entire protein compared to P. aeruginosa MotA (PA4954) and MotB (PA4953) are also shown. (A) Alignment of the first 70 amino acids of the MotA and MotC homologues. (B) Alignment of the first 70 amino acids of the MotB and MotD homologues. Highlighted boxes indicate highly conserved residues.

The E. coli MotA protein has a higher percent identity to PA4954 (42%) than to PA1460 (24%). Similarly, the E. coli MotB protein has a higher percent identity to PA4953 (38%) than to PA1461 (27%). Based on their sequence identity and similarity to the well-characterized E. coli proteins, as well as the current PAO1 genome annotation, we propose to designate PA4954 and PA4953 as MotA and MotB and PA1460 and PA1461 as MotC and MotD, respectively.

A BLAST search with MotA and MotB against all bacterial genomes available to date (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sutils/genom_table.cgi) showed that the MotAB and MotCD proteins can be found in all sequenced pseudomonads (Fig. 1) as well as in some other gram-negative bacteria, such as the xanthomonads (members of the γ-subdivision of the proteobacteria, which includes the pseudomonads and E. coli) and Chromobacterium violaceum (a member of the β-subdivision of the proteobacteria). In contrast, only the motAB genes, but not the motCD genes, could be found in E. coli and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium (γ-subdivision). Yersinia pestis (γ-subdivision) and Burkholderia cepacia (β-subdivision) do not have an apparent homologue of the MotCD proteins but instead seem to have two copies of the motAB genes. The genetic arrangement of the motAB and motCD genes found in P. aeruginosa is also conserved in all other organisms containing these genes, except for C. violaceum, in which the motCD genes are not found adjacent to genes encoding the chemotaxis system. Interestingly, Desulfovibrio vulgaris has four stators, three of which have different degrees of similarity to MotAB and MotCD and one which has sequence similarity to the Na+-powered pomAB-encoded stator of Vibrio spp. (21). A search of the complete genome of Bacillus subtilis and related Bacillus spp. revealed two putative copies of stator proteins (34), both of which shared higher sequence similarity to MotCD than to MotAB (data not shown). Listeria monocytogenes and Clostridium spp. appear to be the only other sequenced gram-positive organisms that have at least two putative copies of stator proteins (data not shown).

A protein sequence alignment performed using the MacVector software (Accelrys Inc., San Diego, Calif.) showed that the residues known to be essential in the E. coli proteins MotA (including Arg90, Glu98, Pro173, and Pro222) and MotB (Asp32) (8, 33) are present in all putative homologues identified in this study (data not shown). Our analysis shows that two putative stator families can be identified in some gram-negative and gram-positive organisms; however, these data also suggest that there is no obvious relationship between the presence of the two stators and a specific bacterial group.

Construction of ΔmotAB, ΔmotCD, and ΔmotAB ΔmotCD mutants.

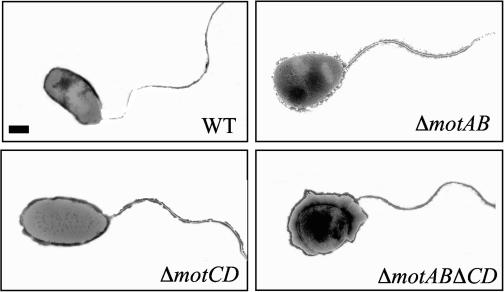

To explore the role of the two putative stators in P. aeruginosa motility, we constructed single and double deletion mutants in the strain PA14 (44). These constructs were obtained using the following protocol: primer pairs CT30-CT31 and CT32-CT33 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were used to amplify ∼1 kb directly upstream of the start codon of motC (PA1460) and downstream of the stop codon of motD (PA1461), respectively. Primers CT31 and CT32 introduced a common restriction site (HindIII) that facilitated ligation of these two fragments. The resulting ∼2-kb fragment was then amplified by PCR using CT30 and CT33, which introduced two restriction sites (BamHI and EcoRI) allowing the cloning of the fragment into pEX18-Gm digested with these same enzymes (25). The resulting plasmid, pEX18-motCD, was used to build a deletion of motCD (ΔmotCD) as previously described (25). The deletion of the genes coding for MotA and MotB was obtained following the same protocol outlined above, with the primer pairs CT25-CT26 and CT27-CT28. We obtained the double mutant of the putative stators by following the protocol described above, using the mutant ΔmotAB as recipient and the E. coli derivative containing pEX18-motCD as donor. The presence of each deletion was then checked by PCR using the following pairs: CT25-CT47 and CT26-CT46 for motAB and CT48-CT50 and CT30-CT49 for motCD. None of the mot mutants had a detectable growth defect (data not shown). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) showed that all mutants had a polar flagellum identical to that of the wild type (WT) (Fig. 2). The TEM samples were prepared from liquid cultures. A Formvar-coated copper grid (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Fort Washington, Pa.) was placed on the surface of 1 drop (5 μl) of the cell suspension for 3 min. The grid was then removed and stained for 3 min with a fresh solution of 1% phosphotungstic acid (pH 7.0). The negatively stained cells were visualized by TEM (JEM 100 CX TEM; JEOL USA, Peabody, Mass.).

FIG. 2.

Representative transmission electron micrograph of the WT, ΔmotAB, ΔmotCD, and ΔmotAB ΔmotCD mutants, showing the presence of the polar flagellum. Bar, 200 nM.

Characterization of the deletion mutants for flagellum-dependent swimming and swarming motility on semisolid agar medium.

The flagellum-dependent swimming motility of the WT and mutants was measured in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium solidified with 0.3% agar. Plates were inoculated with 5 μl of an overnight culture of each strain on the agar surface and then incubated at 30°C for 20 h. Table 1 presents quantitative data for each of the three mot mutants, the WT strain, and the flgK mutant (43), which lacks a flagellum. The single mutants (ΔmotAB and ΔmotCD) showed no defect in swimming compared to the WT strain, whereas the double mutant (ΔmotAB ΔmotCD) could not swim under our experimental conditions (Table 1). As expected, the flgK mutant was also defective for swimming motility. These data suggest that the motAB- and motCD-encoded proteins are functionally redundant for swimming motility under these experimental conditions.

TABLE 1.

Swimming and twitching motilitya

| Strain | Zone diam (mm)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Swimming | Twitching | |

| WT | 35.3 ± 2.0 | 19.6 ± 0.5 |

| ΔmotCD | 32.2 ± 1.7 | 16.2 ± 0.8 |

| ΔmotAB | 33.7 ± 1.5 | 17.4 ± 0.9 |

| ΔmotABΔmotCD | 5.7 ± 0.8 | 16.2 ± 1.3 |

| flgK::Tn5 | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 17.8 ± 0.4 |

Motility was determined by measuring the diameter (in millimeters) of the zone of expansion from the point of inoculation. The standard deviation was determined from five different experiments.

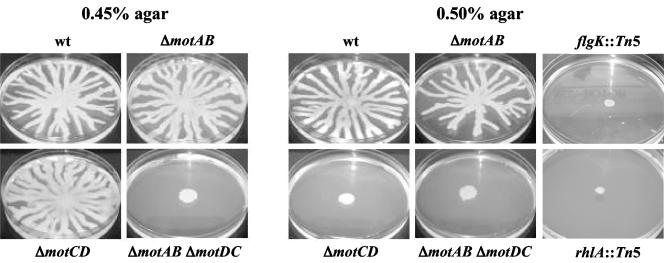

Recent studies showed that P. aeruginosa is able to swarm in semisolid environments (31, 45). P. aeruginosa strain PA14 forms a swarming pattern characterized by branches or tentacles spreading from the inoculation point, as shown in Fig. 3. Swarming behavior in this organism is dependent upon the flagellum and production of rhamnolipid surfactants (Fig. 3, right panels). The mot mutant strains produced equivalent amounts of rhamnolipid surfactants as the WT, as measured on cetyltrimethylammonium bromide medium by following a protocol modified from that of Köhler et al. (31), wherein 0.5% Casamino Acids was provided as the nitrogen source and trace minerals were omitted.

FIG. 3.

(Left) Swarming motility of the WT strain as well as the single mutants ΔmotAB and ΔmotCD and the double mutant ΔmotAB ΔmotCD on plates containing 0.45% agar. (Right) The swarming phenotype of these same strains plus the nonflagellated flgK and non-rhamnolipid-producing rhlA mutants was assessed on 0.5% agar. See Table 2 for quantitative data.

We tested swarming motility of the mutants by inoculating 5 μl of an overnight, LB-grown culture onto a swarming plate followed by incubation at 37°C for 20 h. The protocol used for the swarming plates was modified from that of Köhler et al. (31) as follows: M8 medium was supplemented with 0.2% glucose, 1 mM MgSO4, and 0.5% Casamino Acids. Swarming motility is traditionally observed in plates containing 0.4 to 2% agar, depending upon the organism (20). Swarming motility plates were prepared the same day of their use and, after solidification of agar, were dried for 5 min under sterile air and inoculated. Here, various agar concentrations between 0.4 and 0.8% were tested, and these data are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 3.

TABLE 2.

Swarming motilitya

| Strain | Maximal expansion (mean ± SD) in agar concn of:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.45% | 0.5% | 0.6% | 0.7% | 0.8% | |

| WT | 42.4 ± 2.5 | 45.0 ± 2.5 | 29.5 ± 2.3 | 8.5 ± 1.7 | 8 ± 1.4 |

| ΔmotCD | 43.2 ± 2.9 | 6.3 ± 0.6 | 7.3 ± 0.6 | 5.7 ± 1.2 | 5.3 ± 0.6 |

| ΔmotAB | 41.3 ± 2.5 | 42.9 ± 2.2 | 21.9 ± 4.3 | 7.5 ± 0.7 | 5.5 ± 0.7 |

| ΔmotABΔmotCD | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 7.7 ± 1.2 | 6.3 ± 0.6 | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 5.5 ± 0.7 |

| flgK::Tn5 | 6.7 ± 0.6 | 6.3 ± 0.6 | 6.7 ± 0.6 | 5.5 ± 0.7 | 5.5 ± 0.7 |

| pilB::Tn5 | 42.4 ± 3.1 | 45.8 ± 3.2 | 25.7 ± 3.5 | NT | NT |

Shown is the maximal swarming expansion in M8 medium with different agar concentrations. For the swarming-positive strains, values were determined by measuring (in millimeters) 10 of the longest tentacles per plate (from three plates). For the swarming-negative strains, values were determined by measuring the radius (in millimeters) of the growth at the inoculation point (from three plates). NT, not tested.

The ΔmotAB mutant is able to swarm as well as the WT in agar concentrations up to 0.7%. P. aeruginosa PA14 does not swarm in medium containing greater than 0.7% agar, and swarming is decreased at these high concentrations even for the WT. In contrast, the ΔmotCD mutant can swarm to a degree comparable to that of the WT in a relatively low agar concentration (0.45%), but not at higher concentrations tested (above or equal to 0.5%). The double mutant ΔmotAB ΔmotCD is not able to swarm under any of the conditions tested. As expected, the flgK mutant, which lacks the flagellum, and a rhamnolipid mutant are unable to swarm. These data indicate that the MotAB and MotCD proteins are not completely functionally redundant for swarming motility.

In some organisms swarming motility is associated with cell elongation and the elaboration of lateral flagella (16, 39). Phase-contrast images acquired with OpenLab software were used to determine the length of the cells, and only a small difference was seen for the WT cells at the center of the swarm (2.77 ± 0.62 μm [mean ± standard deviation]; n = 96) versus the edge of the swarm (3.47 ± 0.64 μm; n = 116). Furthermore, the sizes of the cells in the center and edge of the swarm were determined to be similar to those of the WT for the ΔmotAB (center, 2.75 ± 0.57 μm, n = 145; edge, 3.28 ± 0.59 μm, n = 140), ΔmotCD (center, 2.56 ± 0.59 μm, n = 175; edge, 3.39 ± 0.68 μm, n = 146) and ΔmotAB ΔmotCD (center, 2.76 ± 0.57 μm, n = 164; edge, 3.37 ± 0.56 μm, n = 134) strains. This difference in cell length between cells at the edge and the center of the swarm was similar to that observed for cells grown planktonically in M8 medium when measured in stationary phase (2.45 ± 0.43 μm, n = 138) versus exponential phase (3.48 ± 0.66 μm, n = 139), suggesting that the smaller cells at the center of the swarm were nutrient limited. Similar results regarding the size of the cells were observed by TEM (data not shown), and no lateral flagella were observed for P. aeruginosa PA14, as reported previously for strain P. aeruginosa PA01 (31, 45). Finally, no Na+-stimulated motility was observed with 1% tryptone medium (data not shown), as described previously (30) and as has been shown for organisms with Na+-powered stators (2, 18, 40, 42), suggesting that motility in P. aeruginosa PA14 is not powered by this ion.

Measuring motility in liquid medium.

We assessed swimming motility microscopically at room temperature, as described elsewhere (8), in 3 and 15% Ficoll (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, Mo.). Approximately 50 cells were measured for each strain at each Ficoll concentration. Swimming speed was calculated in micrometers per second from time-lapse images captured on a Leica DM IRB inverted microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a charge-coupled device digital camera and a 63× PL Flotar objective lens and using a G4 Macintosh computer with the OpenLab software package (Improvision, Coventry, England). These data are summarized in Fig. 4.

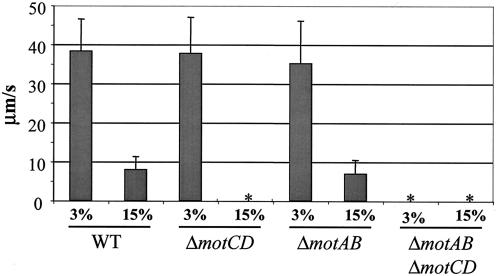

FIG. 4.

Swimming motility of the WT and mot mutants was measured microscopically at 3 and 15% Ficoll in M63 minimal medium supplemented with 0.2% glucose. Swimming speed was measured in micrometers per second and was determined from the analysis of ∼50 cells per strain per condition. An asterisk indicates that a strain was nonmotile under the conditions tested.

At 3% Ficoll, a relatively low-viscosity solution, the WT swam at 38.3 ± 8.2 μm/s, a speed indistinguishable from that of the ΔmotAB (35.2 ± 10.9 μm/s) and ΔmotCD (37.8 ± 9.2 μm/s) mutants. At 15% Ficoll, a relatively high-viscosity solution, the WT moved at a speed of 7.93 ± 3.3 μm/s, a speed slightly faster than that of the ΔmotAB mutant (6.93 ± 3.5 μm/s) but within the experimental error. The ΔmotCD mutant was completely nonmotile under these conditions. As expected, the ΔmotAB ΔmotCD mutant was nonmotile under all conditions tested.

Complementation analysis.

We performed complementation analysis of the ΔmotAB ΔmotCD mutant. The motAB and motCD genes were cloned under the control of the Plac promoter in vector pMMB66EH (17). Primer pair CT57 and CT64 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were used to amplify the motAB genes. The motCD genes were amplified with the CT61 and CT63 primers. The PCR fragments were cloned in pMMB66EH using the enzymes HindIII and EcoRI (introduced by primers CT57 and CT61 and primers CT64 and CT63, respectively), resulting in the plasmids pMMB66EH-motAB and pMMB66EH-motCD. These plasmids, as well as the pMMB66EH vector, were introduced into the ΔmotAB ΔmotCD double mutant by conjugation, and the resulting strains were tested for swarming motility. The ΔmotAB ΔmotCD/pMMB66EH-motCD strain swarmed (31.8 ± 2.5 mm) to a degree comparable to that of the WT (42.2 ± 4.2 mm) on 0.5% agar supplemented with 0.25 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to induce the Plac promoter. No complementation was observed in the absence of IPTG. The pMMB66EH-motCD plasmid also partially complemented the swimming defect of the ΔmotAB ΔmotCD mutant (data not shown). As expected, the ΔmotAB ΔmotCD mutant and the ΔmotAB ΔmotCD mutant carrying the pMMB66EH vector did not swarm or swim.

The ΔmotAB ΔmotCD/pMMB66EH-motAB strain (which is functionally a ΔmotCD mutant) did not swarm on 0.5% agar (as expected) or 0.45% agar. However, the swarming motility of a ΔmotAB strain (which is capable of swarming [37.2 ± 4.8 mm]) is completely inhibited by the introduction of the pMMB66EH-motAB plasmid with or without added IPTG (6.0 ± 0.0 mm). Introduction of the pMMB66EH vector had no effect on swarming of the ΔmotAB strain (31.3 ± 3.0 mm). These data suggest that introduction of the MotAB stator in multicopy can inhibit swarming. Previous studies in E. coli also suggested that stator function is sensitive to copy number (48).

The MotAB and MotCD proteins are not required for twitching motility in P. aeruginosa PA14.

We tested the single and double mot mutants for twitching motility in order to determine whether the deletion mutations had an effect on the function of the TFP. To measure twitching motility, we used thin LB plates prepared with 1.5% agar, as reported previously (43). The twitching zone was measured as the diameter (in millimeters) of the expansion of the cells from the inoculation point at the plastic-agar interface after incubation for 16 h at 37°C and then for 24 h at 25°C. The results presented in Table 1 show that no defect in twitching motility could be observed for any of the strains.

We also showed that the TFP are not necessary for swarming in P. aeruginosa PA14 (Table 2). In addition to testing the pilB mutant (43), we showed that mutations in pilA (38 ± 4.0 mm), pilY1 (28.4 ± 2.2 mm), pilO (35.3 ± 5.9 mm), and pilU (39.8 ± 4.1 mm) have no effect on swarming motility on 0.5% agar in M8 medium. Similar results were obtained in LB medium and Difco medium supplemented with 0.5% glucose (data not shown). These independently isolated TFP mutations map to four different gene clusters coding for TFP proteins. Therefore, we can conclude that TFP are not required for swarming motility in P. aeruginosa PA14. These data are in accordance with those of Rashid and Kornberg (45), but in contradiction to the results of Köhler et al. (31). The reason for the phenotypic difference in the Köhler et al. report is unclear (31).

Conclusions.

In this study we identified two putative sets of stator proteins in P. aeruginosa by sequence analysis which are conserved among several gram-negative bacteria, including all sequenced pseudomonads. One pair of proteins was designated MotAB (PA4954-4953) based on the current annotation of the P. aeruginosa PAO1 genome and on the sequence similarity of the P. aeruginosa PA4954-4953 proteins to the well-characterized E. coli stator proteins MotAB, including the conservation of key residues essential for stator function. The second putative stator was designated MotCD (PA1460-1461) based on its lower degree of sequence similarity to MotAB. The phenotypic analysis of the deletion mutants demonstrated that the MotAB and MotCD proteins are functionally redundant for swimming, as well as for swarming in relatively low agar concentrations. However, under higher agar concentrations, the ΔmotCD mutant is unable to swarm. The double mutant lacking both motAB and motBC can neither swim nor swarm under any conditions tested, but still makes a flagellum. The plate-based motility assay results were confirmed by measuring swimming speed microscopically. Based on their sequence similarity to the E. coli MotAB proteins and their role in flagellum-mediated motility, we conclude that the MotAB and MotBC proteins are stators that play a role in flagellar motor function for both swimming and swarming motility.

The fact that the motCD mutant, but not the motAB mutant, has a phenotype with respect to swarming suggests that these two stators may have different roles in swarming motility. In a series of elegant studies in E. coli, a mot mutant strain could be complemented by the inducible expression of the MotAB proteins, suggesting that the stators could be the last component assembled into the flagellar machinery (4, 6, 32). Furthermore, the motAB genes in Salmonella are part of the so-called late flagellar genes (35), consistent with the idea that MotAB are incorporated into the flagellum late in biosynthesis. Therefore, although the exact timing of Mot protein insertion is not known, it is possible that P. aeruginosa assembles its flagellar motor de novo and/or reconfigures it with either MotAB stators or MotCD stators (or a mixture of both) depending upon its particular needs. Future studies will address expression and stability of the Mot proteins to better understand how and when the stators are utilized in swimming and swarming motility by P. aeruginosa.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Louisa Howard from the Rippell Electron Microscopy facility at Dartmouth College for her help with the TEM, as well as Shannon Hinsa and Robert Shanks for fruitful discussions. Our thanks also to L. Tisa for helpful suggestions.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (5-KO8-EY-13977-Z to M.E.Z. and R01 A151360-01 and P20 RR018787 to G.A.O.) and the Pew Charitable Trusts. G.A.O. is a Pew Scholar in the Biomedical Sciences.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://jb.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asai, Y., T. Yakushi, I. Kawagishi, and M. Homma. 2003. Ion-coupling determinants of Na+-driven and H+-driven flagellar motors. J. Mol. Biol. 327:453-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blair, D. F. 2003. Flagellar movement driven by proton translocation. FEBS Lett. 545:86-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blair, D. F., and H. C. Berg. 1988. Restoration of torque in defective flagellar motors. Science 242:1678-1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blattner, F. R., G. Plunkett III, C. A. Bloch, N. T. Perna, V. Burland, M. Riley, J. Collado-Vides, J. D. Glasner, C. K. Rode, G. F. Mayhew, J. Gregor, N. W. Davis, H. A. Kirkpratick, M. A. Goeden, D. J. Rose, B. Mau, and Y. Shao. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Block, S. M., and H. C. Berg. 1984. Successive incorporation of force-generating units in the bacterial rotary motor. Nature 309:470-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun, T. F., and D. F. Blair. 2001. Targeted disulfide cross-linking of the MotB protein of Escherichia coli: evidence for two H+ channels in the stator complex. Biochemistry 40:13051-13059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun, T. F., S. Poulson, J. B. Gully, J. C. Empey, S. Van Way, A. Putnam, and D. F. Blair. 1999. Function of proline residues of MotA in torque generation by the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 181:3542-3551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chun, S. Y., and J. S. Parkinson. 1988. Bacterial motility: membrane topology of the Escherichia coli MotB protein. Science 239:276-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dean, G. E., R. M. Macnab, J. Stader, P. Matsumura, and C. Burks. 1984. Gene sequence and predicted amino acid sequence of the MotA protein, a membrane-associated protein required for flagellar rotation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 159:991-999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Mot, R., and J. Vanderleyden. 1994. The C-terminal sequence conservation between OmpA-related outer membrane proteins and MotB suggests a common function in both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, possibly in the interaction of these domains with peptidoglycan. Mol. Microbiol. 12:333-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Enomoto, M. 1966. Genetic studies of paralyzed mutant in Salmonella. I. Genetic fine structure of the mot loci in Salmonella typhimurium. Genetics 54:715-726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Enomoto, M. 1966. Genetic studies of paralyzed mutant in Salmonella. II. Mapping of three mot loci by linkage analysis. Genetics 54:1069-1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrandez, A., A. C. Hawkins, D. T. Summerfield, and C. S. Harwood. 2002. Cluster II che genes from Pseudomonas aeruginosa are required for an optimal chemotactic response. J. Bacteriol. 184:4374-4383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francis, N. R., G. E. Sosinsky, D. Thomas, and D. J. DeRosier. 1994. Isolation, characterization and structure of bacterial flagellar motors containing the switch complex. J. Mol. Biol. 235:1261-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fraser, G. M., and C. Hughes. 1999. Swarming motility. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2:630-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furste, J. P., W. Pansegrau, R. Frank, H. Blocker, P. Scholz, M. Bagdasarian, and E. Lanka. 1986. Molecular cloning of the plasmid RP4 primase region in a multi-host-range tacP expression vector. Gene 48:119-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gosink, K. K., and C. C. Hase. 2000. Requirements for conversion of the Na+-driven flagellar motor of Vibrio cholerae to the H+-driven motor of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 182:4234-4240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harshey, R. M. 2003. Bacterial motility on a surface: many ways to a common goal. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57:249-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harshey, R. M. 1994. Bees aren't the only ones: swarming in gram-negative bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 13:389-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heidelberg, J. F., R. Seshadri, S. A. Haveman, C. L. Hemme, I. T. Paulsen, J. F. Kolonay, J. A. Eisen, N. Ward, B. Methe, L. M. Brinkac, S. C. Daugherty, R. T. Deboy, R. J. Dodson, A. S. Durkin, R. Madupu, W. C. Nelson, S. A. Sullivan, D. Fouts, D. H. Haft, J. Selengut, J. D. Peterson, T. M. Davidsen, N. Zafar, L. Zhou, D. Radune, G. Dimitrov, M. Hance, K. Tran, H. Khouri, J. Gill, T. R. Utterback, T. V. Feldblyum, J. D. Wall, G. Voordouw, and C. M. Fraser. 2004. The genome sequence of the anaerobic, sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. Nat. Biotechnol. 22:554-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henrichsen, J. 1972. Bacterial surface translocation: a survey and a classification. Microbiol. Rev. 36:478-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Henrichsen, J. 1983. Twitching motility. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 37:81-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirota, N., and Y. Imae. 1983. Na+-driven flagellar motors of an alkalophilic Bacillus strain YN-1. J. Biol. Chem. 258:10577-10581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoang, T. T., R. R. Karkhoff-Schweizer, A. J. Kutchma, and H. P. Schweizer. 1998. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene 212:77-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hogan, D. A., and R. Kolter. 2002. Pseudomonas-Candida interactions: an ecological role for virulence factors. Science 296:2229-2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hong, C. S., M. Shitashiro, A. Kuroda, T. Ikeda, N. Takiguchi, H. Ohtake, and J. Kato. 2004. Chemotaxis proteins and transducers for aerotaxis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 231:247-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato, J., T. Nakamura, A. Kuroda, and H. Ohtake. 1999. Cloning and characterization of chemotaxis genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 63:155-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan, I. H., T. S. Reese, and S. Khan. 1992. The cytoplasmic component of the bacterial flagellar motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:5956-5960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kiiyukia, C., H. Kawakami, and H. Hashimoto. 1993. Effect of sodium chloride, pH and organic nutrients on the motility of Vibrio cholerae non-01. Microbios 73:249-255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Köhler, T., L. K. Curty, F. Barja, C. van Delden, and J. C. Pechere. 2000. Swarming of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is dependent on cell-to-cell signaling and requires flagella and pili. J. Bacteriol. 182:5990-5996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kojima, S., and D. F. Blair. 2004. The bacterial flagellar motor: structure and function of a complex molecular machine. Int. Rev. Cytol. 233:93-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kojima, S., and D. F. Blair. 2001. Conformational change in the stator of the bacterial flagellar motor. Biochemistry 40:13041-13050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kunst, F., N. Ogasawara, I. Moszer, A. M. Albertini, G. Alloni, V. Azevedo, M. G. Bertero, P. Bessieres, A. Bolotin, S. Borchert, R. Borriss, L. Boursier, A. Brans, M. Braun, S. C. Brignell, S. Bron, S. Brouillet, C. V. Bruschi, B. Caldwell, V. Capuano, N. M. Carter, S. K. Choi, J. J. Codani, I. F. Connerton, A. Danchin, et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Nature 390:249-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kutsukake, K., Y. Ohya, and T. Iino. 1990. Transcriptional analysis of the flagellar regulon of Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 172:741-747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larsen, S. H., J. Adler, J. J. Gargus, and R. W. Hogg. 1974. Chemomechanical coupling without ATP: the source of energy for motility and chemotaxis in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 71:1239-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Masduki, A., J. Nakamura, T. Ohga, R. Umezaki, J. Kato, and H. Ohtake. 1995. Isolation and characterization of chemotaxis mutants and genes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 177:948-952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matz, C., T. Bergfeld, S. A. Rice, and S. Kjelleberg. 2004. Microcolonies, quorum sensing and cytotoxicity determine the survival of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms exposed to protozoan grazing. Environ. Microbiol. 6:218-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCarter, L. L. 2004. Dual flagellar systems enable motility under different circumstances. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 7:18-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCarter, L. L. 1994. MotY, a component of the sodium-type flagellar motor. J. Bacteriol. 176:4219-4225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Merz, A. J., M. So, and M. P. Sheetz. 2000. Pilus retraction powers bacterial twitching motility. Nature 407:98-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okabe, M., T. Yakushi, M. Kojima, and M. Homma. 2002. MotX and MotY, specific components of the sodium-driven flagellar motor, colocalize to the outer membrane in Vibrio alginolyticus. Mol. Microbiol. 46:125-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'Toole, G. A., and R. Kolter. 1998. Flagellar and twitching motility are necessary for Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Mol. Microbiol. 30:295-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rahme, L. G., E. J. Stevens, S. F. Wolfort, J. Shao, R. G. Tompkins, and F. M. Ausubel. 1995. Common virulence factors for bacterial pathogenicity in plants and animals. Science 268:1899-1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rashid, M. H., and A. Kornberg. 2000. Inorganic polyphosphate is needed for swimming, swarming, and twitching motilities of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:4885-4890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simpson, D. A., and D. P. Speert. 2000. RpmA is required for nonopsonic phagocytosis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 68:2493-2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stover, C. K., X. Q. Pham, A. L. Erwin, S. D. Mizoguchi, P. Warrener, M. J. Hickey, F. S. Brinkman, W. O. Hufnagle, D. J. Kowalik, M. Lagrou, R. L. Garber, L. Goltry, E. Tolentino, S. Westbrock-Wadman, Y. Yuan, L. L. Brody, S. N. Coulter, K. R. Folger, A. Kas, K. Larbig, R. Lim, K. Smith, D. Spencer, G. K. Wong, Z. Wu, and I. T. Paulsen. 2000. Complete genome sequence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA01, an opportunistic pathogen. Nature 406:959-964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Way, S. M., E. R. Hosking, T. F. Braun, and M. D. Manson. 2000. Mot protein assembly into the bacterial flagellum: a model based on mutational analysis of the motB gene. J. Mol. Biol. 297:7-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamaguchi, S., H. Fujita, A. Ishihara, S. Aizawa, and R. M. Macnab. 1986. Subdivision of flagellar genes of Salmonella typhimurium into regions responsible for assembly, rotation, and switching. J. Bacteriol. 166:187-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou, J., and D. F. Blair. 1997. Residues of the cytoplasmic domain of MotA essential for torque generation in the bacterial flagellar motor. J. Mol. Biol. 273:428-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou, J., R. T. Fazzio, and D. F. Blair. 1995. Membrane topology of the MotA protein of Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 251:237-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhou, J., L. L. Sharp, H. L. Tang, S. A. Lloyd, S. Billings, T. F. Braun, and D. F. Blair. 1998. Function of protonatable residues in the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli: a critical role for Asp32 of MotB. J. Bacteriol. 180:2729-2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.