Abstract

The reactivities of four evolutionarily divergent extradiol dioxygenases towards mono-, di-, and trichlorinated (triCl) 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyls (DHBs) were investigated: 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase (EC 1.13.11.39) from Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 (DHBDLB400), DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III from Rhodococcus globerulus P6, and 2,2′,3-trihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase from Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1 (THBDRW1). The specificity of each isozyme for particular DHBs differed by up to 3 orders of magnitude. Interestingly, the Kmapp values of each isozyme for the tested polychlorinated DHBs were invariably lower than those of monochlorinated DHBs. Moreover, each enzyme cleaved at least one of the tested chlorinated (Cl) DHBs better than it cleaved DHB (e.g., apparent specificity constants for 3′,5′-dichlorinated [diCl] DHB were 2 to 13.4 times higher than for DHB). These results are consistent with structural data and modeling studies which indicate that the substrate-binding pocket of the DHBDs is hydrophobic and can accommodate the Cl DHBs, particularly in the distal portion of the pocket. Although the activity of DHBDP6-III was generally lower than that of the other three enzymes, six of eight tested Cl DHBs were better substrates for DHBDP6-III than was DHB. Indeed, DHBDP6-III had the highest apparent specificity for 4,3′,5′-triCl DHB and cleaved this compound better than two of the other enzymes. Of the four enzymes, THBDRW1 had the highest specificity for 2′-Cl DHB and was at least five times more resistant to inactivation by 2′-Cl DHB, consistent with the similarity between the latter and 2,2′,3-trihydroxybiphenyl. Nonetheless, THBDRW1 had the lowest specificity for 2′,6′-diCl DHB and, like the other enzymes, was unable to cleave this critical PCB metabolite (kcatapp < 0.001 s−1).

The microbial degradation of aromatic compounds plays a critical role in the global carbon cycle. Many particularly persistent environmental pollutants are aromatic molecules, including the structurally diverse polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). A wide number of microorganisms are able to aerobically transform some of the 209 possible PCB congeners via the bph pathway, which degrades biphenyl to benzoate and 2-hydroxypenta-2,4-dienoate (1, 16). However, the enzymatic activities of this pathway are insufficient to degrade all congeners or mixtures thereof. In fact, the range of PCBs that is transformed by the bph pathway is highly dependent upon the bacterial strain: some strains are unable to transform PCBs containing more than three chlorines, whereas other strains, such as Burkholderia sp. strain LB400, transform up to hexachlorinated biphenyls (7, 22).

A critical step in improving the microbial catabolic activities for the degradation of PCBs is understanding the reactivities of the four enzymes of the bph pathway for PCB metabolites. This includes determining the enzymes' specificities for these metabolites. Considerable effort has been directed towards characterizing and engineering biphenyl dioxygenase, the first enzyme of the pathway (for recent examples see references 6, 15, and 32). The second enzyme of the pathway was proposed to have a very broad substrate specificity, in part because it catalyzes the dehydrogenation of 3,4-dihydro-3,4-dihydroxy-2,2′,5,5′-tetrachlorobiphenyl at a very low rate (5). However, a subsequent study showed that it limits the degradation of some PCBs (9). The fourth enzyme of the pathway has also been identified as an important determinant of PCB degradation, as it is competitively inhibited by some chlorinated (Cl) metabolites (29, 30).

2,3-Dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenase (DHBD; EC 1.13.11.39) is the third enzyme of the bph pathway. It utilizes a mononuclear nonheme iron(II) center to cleave 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl (DHB) in an extradiol fashion (Fig. 1). Early studies using whole cells indicated that this enzyme limits the degradation of certain PCB congeners by Alcaligenes sp. strain Y42 and Acinetobacter sp. strain P6 (now Rhodococcus globerulus P6) (17). DHBD also limited the degradation of some congeners by the bph pathway of Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 when this pathway was heterologously expressed in Escherichia coli (31). More recent studies using purified enzyme preparations demonstrated that DHBDLB400 from Burkholderia sp. strain LB400 cleaves Cl DHBs with lower specificity than that for unchlorinated DHB, is more susceptible to oxidative inactivation during cleavage of Cl DHBs, and is competitively inhibited by 2′,6′-dichloro-2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl (2′,6′-diCl DHB; Kic = 7 nM) (11). In contrast, DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III, two evolutionarily divergent isozymes from the PCB-degrading R. globerulus P6 (2, 3), had markedly different reactivities compared to that of DHBDLB400 (37). However, DHBDP6-I and DHBDP6-III shared the relative inability of DHBDLB400 to cleave 2′,6′-dichlorinated (diCl) DHB. A promising candidate to degrade ortho-chlorinated metabolites is 2,2′,3-trihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase from Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1 (THBDRW1), which cleaves a structural analog of 2′-Cl DHB in an extradiol fashion (Fig. 1) (20). McKay et al. (24) demonstrated that five DHBDs (the four mentioned above and DHBDP6-II) have different reactivities with Cl DHBs. However, the results of these studies are harder to interpret, as the authors used partially inactive enzyme preparations and did not take into account the effects of oxidative inactivation of the enzymes during catalytic turnover. Moreover, comparisons of the five DHBDs were performed using impure Cl DHBs at a single substrate concentration: steady-state parameters were determined for only the three P6 isozymes for three monochlorinated (monoCl) DHBs.

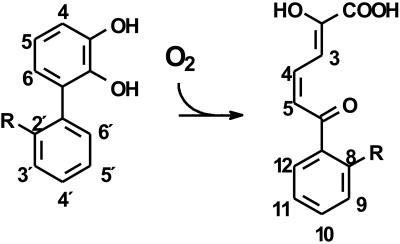

FIG. 1.

Reaction catalyzed by DHBD and related enzymes. In the aerobic catabolism of biphenyl, DHBD catalyzes a reaction in which R = H. In the aerobic catabolism of dibenzofuran, THBDRW1 catalyzes a reaction in which R = OH.

Herein we extend our studies of the extradiol cleavage of PCB metabolites by reporting the reactivities of highly active DHBDLB400, DHBDP6-I, DHBDP6-III, and THBDRW1 towards several highly pure diCl and trichlorinated (triCl) DHBs. Steady-state kinetic studies were conducted to determine the apparent specificities of the enzyme for each DHB. In addition, the suicide inhibition of these enzymes by each of the DHBs was studied. The results are discussed with respect to the reactivity of each enzyme as well as the potential use of protein and genetic engineering to improve the PCB-degrading capabilities of bacterial strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals.

DHB, 4-Cl, 5-Cl, 6-Cl, 2′-Cl, 3′-Cl, 4′-Cl, 5,3′-diCl DHB, 3′,5′-diCl DHB, 2′,6′-diCl DHB, and 4,3′5′-triCl DHB were synthesized according to standard procedures (25). Ferene S was from ICN Biomedicals Inc. (Costa Mesa, Calif.). All other chemicals were of analytical grade and used without further purification.

Strains, media, and growth.

E. coli strain DH5α was used for DNA propagation and was cultured at 37°C and 200 rpm in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth with the appropriate antibiotics. Pseudomonas putida KT2442 (21) transformed with pVLT31 (12) derivatives was used for overexpression and was cultured at 30°C and 250 rpm in LB broth with 20 μg of tetracycline/ml supplemented with phosphate buffer and mineral salts as previously described (35).

Construction of plasmids and overexpression.

DNA was manipulated using standard protocols (4). The gene encoding THBDRW1, dbfB, was amplified by PCR from the chromosomal DNA of Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1 and two oligonucleotides: 5′RW1 (5′-AGTTATCCATATGTCAGTAAAACAA-3′) (introduced NdeI site underlined) and 3′RW1 (5′-CGCGGATCCTTCGTCACTACG-3′ ) (introduced C.BamHI site underlined). The PCR was performed using the Pwo DNA polymerase (Roche Applied Sciences, Laval, Quebec, Canada) according to the manufacturer's instructions and an annealing temperature of 45°C. The resulting amplicon was digested with NdeI and BamHI and cloned in pT7-7 (33), yielding pT7-7dbfB. The cloned gene was sequenced on an ABI 373 Strech (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) sequencer by using Big-Dye terminators to confirm its authenticity. The gene was then subcloned as an XbaI fragment into the pVLT31 vector, yielding pAHD1. THBDRW1 was overexpressed in P. putida KT2442 freshly transformed with pAHD1 essentially as previously described for DHBDs (35, 37).

Protein purification.

Unless otherwise specified, all manipulations were performed under an inert atmosphere in an M. Braun Labmaster 100 glovebox (Newburyport, Mass.) maintained at 2 ppm of O2 or less. Buffers were prepared and made anaerobic as described previously (35, 37). All chromatography steps were performed on an ÄKTA Explorer (Amersham Biosciences, Baie d'Urfé, Quebec, Canada) configured to maintain an anaerobic atmosphere during purification, as previously described (35). DHBDLB400, DHBDP6-I, and DHBDP6-III enzymes were purified to apparent homogeneity according to published protocols (35, 37).

THBDRW1 was purified using a similar protocol. Briefly, cells from 4 liters of culture were harvested by centrifugation. The cell pellet (approximately 28 g) was resuspended in 36 ml of 50 mM phosphate, pH 7.5, containing 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, and 0.1 mg of DNase I/ml. The cells were disrupted by three successive passages through a French press (Spectronic Instruments Inc., Rochester, N.Y.) operated at a pressure of 20,000 lb/in2. The cell debris was removed by ultracentrifugation in gastight tubes at 37,000 rpm for 90 min in a T1250 rotor (DuPont Instruments, Wilmington, Del.). The clear supernatant was carefully decanted and filtered using a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter (Sartorius AG, Göttingen, Germany). This fluid was referred to as the raw extract.

The raw extract was brought to 20% saturation ammonium sulfate and divided into four equal portions (∼16 ml each). Each portion was loaded onto a Source15 Phenyl (Amersham Biosciences) hydrophobic interaction column (2 by 8 cm) previously equilibrated with 50 mM phosphate (pH 7.5)-2 mM dithiothreitol (buffer A) containing 0.85 M ammonium sulfate. Following the injection of THBDRW1, the column was rinsed with 2 column volumes of buffer A containing 0.85 M ammonium sulfate and 3 column volumes of buffer A containing 0.68 M ammonium sulfate. THBDRW1 activity was eluted using a linear gradient of 0.68 M to 0 M ammonium sulfate in buffer A (8 column volumes). Fractions of 8 ml were collected. Those containing enzyme activity were pooled and equilibrated with 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.5)-10% isopropanol-2 mM dithiothreitol (buffer C) by three rounds of dilution-concentration with a stirred cell concentrator equipped with a YM10 membrane (Amicon, Oakville, Ontario, Canada). The resulting preparation (∼10 ml) was divided into three parts, each of which was loaded onto an HR16/10 MonoQ anion-exchange column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) equilibrated with buffer C. THBDRW1 activity was eluted at a flow of 6 ml/min with a 15-column-volume linear gradient of 0 to 250 mM NaCl in buffer C. Fractions from the three runs containing activity were pooled, concentrated to 3 ml by ultrafiltration, and loaded onto a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200 column (Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated with buffer C containing 50 mM NaCl and 0.25 mM ferrous ammonium sulfate. The protein was eluted at a flow rate of 2.5 ml/min. Fractions (5 ml) exhibiting activities were combined, concentrated to 22 mg of protein/ml, and frozen as beads in liquid N2. Purified THBDRW1 was stored at −80°C for up to 6 months without any significant loss of activity.

Handling of dioxygenase samples.

Aliquots of DHBD were thawed immediately prior to use and were exchanged into 20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazinepropanesulfonic acid (HEPPS)-80 mM NaCl (I = 0.1)-2 mM dithiothreitol (pH 8.0) by gel filtration chromatography (35). Samples of DHBD were further diluted using the same buffer supplemented with 0.1 mg of bovine serum albumin/ml.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis was performed in a Bio-Rad MiniProtean II apparatus, and gels were stained with Coomassie blue according to established procedures (4). Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method (8). Iron concentrations were determined colorimetrically using Ferene S (18).

Kinetic measurements and analysis of steady-state data.

Enzymatic activity was routinely measured by monitoring the formation of 2-hydroxy-6-oxo-6-phenylhexa-2,4-dienoic acid (HOPDA) on a Varian Cary 3 instrument equipped with a thermojacketed cuvette holder. One unit of enzymatic activity was defined as the quantity of enzyme required to produce 1 μmol of HOPDA per min. The amount of enzyme used in each assay was adjusted so that the progress curve was linear for at least 1 min. Initial velocities were determined from a least-squares analysis of the linear portion of the progress curves by using the kinetics module of the Cary software. To determine the Km for O2 of THBDRW1, KmO2, progress curves were obtained using a Clark-type O2 electrode essentially as described previously (35).

All experiments were performed using potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 (I = 0.1 M) at 25.0 ± 0.1°C (∼290 μM dissolved O2). The standard activity assay was performed using 100 μM DHB. Concentrations of active DHBD in the assay were defined by the iron content of the injected purified enzyme solution and were used in calculating specificity and catalytic and inactivation constants. Steady-state rate equations (either the Michaelis-Menten equation or an equation describing a mechanism in which substrate inhibition occurs (see equation 2) (35) were fitted to data by using the least squares and dynamic weighting options of the LEONORA program (10).

Kinetics of inactivation.

Partition ratios for all substrates were determined using the spectrophotometric assay described above and saturating substrate concentrations (i.e., the concentration of DHB exceeded Kmapp by at least 15-fold). The amount of enzyme added to the reaction cuvette was such that the enzyme was completely inactivated before 15% of either the catecholic substrate or O2 was consumed in the reaction mixture. The partition ratio was calculated by dividing the amount of product formed by the amount of active DHBD added to the assay. The progress curves from these same reactions were also used to evaluate the apparent rate constant of inactivation during catalytic turnover in air-saturated buffer, j3app (equation 1) (36). Under the assay conditions, the concentration of free enzyme, [E], is negligible and the partition ratio is equal to the ratio of the catalytic constant kcatapp to the inactivation constant j3app (i.e., Σji = j3).

|

(1) |

For 2′,6′-diCl DHB, j3app was evaluated from the rate constant of saturation js by using equation 2. The latter was determined from progress curves obtained spectrophotometrically at 391 nm from reactions performed at saturating substrate concentrations [S] (100 to 200 μM) by using equation 3.

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

In equation 2, Kmapp is the apparent Km of 2′,6′-diCl DHB in air-saturated buffer. In equation 3, Pi and P∞ are the concentrations of product at the start and end of the assay, respectively, and Pt is the concentration of product formed at time t.

Structural modeling.

The structure of THDBRW1 was modeled using MODELLER 6v2 (28) and the crystallographic coordinates of DHBDLB400 bound to 2′,6′-diCl DHB (Protein Data Bank identifier 1LKD). The amino acid sequences of THBDRW1 and DHBDLB400 were aligned using T-COFFEE (26). The fitting and minimization routines of MODELLER were performed using the default parameters.

RESULTS

Dioxygenase purification.

THBDRW1 was purified anaerobically to >98% apparent homogeneity as judged by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (data not shown). Relevant details of the purification are summarized in Table 1. Over 100 mg of enzyme was obtained from 4 liters of cell culture. Purified THBDRW1 contained greater than 95% of its complement of iron, had a specific activity for DHB of 108 U/mg, and is consistent with the apparent kcat in air-saturated buffer. A previously reported preparation of THBDRW1 had a higher specific activity (454 U/mg [20]) but is inconsistent with the reported Vmax value, which is 4 orders of magnitude lower than the one reported in the present study. Preparations of the three DHBDs were of published quality (35, 37).

TABLE 1.

Purification details of THBDRW1 expressed in P. putida KT2442

| Purification step | Total protein (mg) | Total activitya (U) | Sp act (U/mg) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude extract | 2,647 | 70,270 | 26.6 | 100 |

| Source15 phenyl | 251 | 20,490 | 81.6 | 29 |

| Superdex 200 | 111 | 12,020 | 108.2 | 17 |

Activity units are defined in Materials and Methods.

Physical properties of HOPDAs.

Solutions of the freshly prepared HOPDAs, produced from the DHBD-catalyzed cleavage of the corresponding DHBs in 100 mM phosphate, pH 7.0 (25°C), had the characteristic yellow color of the enolate anion. Accordingly, the absorption spectra of these solutions had wavelengths of maximal absorbance between 392 and 438 nm. The extinction coefficients at the corresponding wavelength for each HOPDA are given in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Molar extinction coefficients of HOPDAs

| DHB | Corresponding HOPDA | Wavelength (nm) | Extinction coefficient (M−1 cm−1)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| DHB | HOPDA | 433 | 11,300 |

| 2′-Cl DHB | 8-Cl HOPDA | 392 | 28,100 |

| 3′-Cl DHB | 9-Cl HOPDA | 436 | 17,500 |

| 4-Cl DHB | 3-Cl HOPDA | 392 | 17,300 |

| 5-Cl DHB | 4-Cl HOPDA | 410 | 20,000 |

| 3′,5′-DiCl DHB | 9,11-DiCl HOPDA | 438 | 19,600 |

| 5,3′-DiCl DHB | 4,9-DiCl HOPDA | 414 | 20,900 |

| 2′,6′-DiCl DHB | 8,12-DiCl HOPDA | 392 | 36,500 |

| 4,3′,5′-TriCl DHB | 3,9,11-TriCl HOPDA | 438 | 24,200 |

Molar extinction coefficients determined in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 25°C, with freshly generated HOPDAs.

Steady-state kinetic analyses.

All four enzymes were able to cleave the investigated Cl DHBs at some rate. However, each enzyme had distinct substrate specificities for DHBs (kAapp in Table 3). Indeed, across the range of enzymes, the specificity for a particular DHB differed by up to 3 orders of magnitude. Nevertheless, each enzyme was able to utilize at least one of the Cl DHBs as a better substrate than unchlorinated DHB. Inspection of the data did not reveal a consistent way to predict the reactivity of the diCl and triCl DHBs from those of the mono-Cl DHBs. For example, the reactivities of DHBDP6-I, DHBDP6-III, and THBDRW1 with 3′-Cl DHB correlated well with their reactivities for 3′,5′-diCl DHB (i.e., the effect of the chloro substituents on the steady-state kinetic parameters appeared to be additive). However, this was not the case for DHBDLB400. This isozyme cleaved 3′,5′-diCl DHB 7.7 times more specifically than DHB while 3′-Cl DHB was a poorer substrate than DHB. Similarly, addition of a 4-Cl substituent had a larger impact on the suitability of DHB as a substrate for DHBDLB400 than on 3′,5′-diCl DHB. One striking feature of the data is that the Kmapp of the enzymes for diCl and triCl DHBs was almost always significantly lower than that for DHB or monoCl DHBs. This was true regardless of the suitability of the diCl or triCl DHB as a substrate.

TABLE 3.

Apparent steady-state kinetic parameters and inactivation parameters of DHBDLB400, DHBDP6-I, DHBDP6-III, and THBDRW1 for Cl DHBsa

| Enzyme | Substrate | KmAapp (μM) | kiAapp (mM) | kcatapp (s−1) | kAapp (106 M−1 s−1) | Partition ratio | j3app (10−3 s−1) | j3app/KmAapp (103 M−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DHBDLB400 | DHBd | 6.9 (0.7) | 3.6 (0.9) | 270 (6) | 39 (3) | 113,400 (600) | 2.4 (0.1) | 0.35 (0.05) |

| 2′-Cl DHBd | 6.4 (0.5) | 2.3 (0.4) | 4.9 (0.1) | 0.76 (0.06) | 1,660 (300) | 2.9 (0.6) | 0.45 (0.13) | |

| 3′-Cl DHBd | 58 (5) | 0.40 (0.05) | 305 (20) | 5.3 (0.2) | 42,000 (14,000) | 7.3 (2.9) | 0.13 (0.06) | |

| 4-Cl DHBd | 16.4 (1.8) | 3.5 (1.1) | 60.6 (2.2) | 3.7 (0.3) | 14,200 (760) | 4.3 (0.4) | 0.26 (0.05) | |

| 3′,5′-DiCl DHB | 0.62 (0.07) | 0.100 (0.035) | 184 (6) | 300 (25) | 59,200 (500) | 2.0 (0.36) | 3.2 (0.9) | |

| 2′,6′-DiCl DHBd | 0.007 (0.001) | —b | 0.036 (0.001) | 5.1 (0.9) | 49.5 (1.6) | 0.69 (0.01) | 99 (16) | |

| 4,3′,5′-TriCl DHB | 1.1 (0.27) | — | 5.5 (0.3) | 5.1 (0.4) | 670 (90) | 7.6 (0.6) | 7.0 (2.3) | |

| DHBDP6-I | DHBd | 5.8 (1.0) | 2.2 (0.7) | 78 (3) | 13.3 (1.9) | 31,100 (3,300) | 2.5 (0.4) | 0.43 (0.14) |

| 2′-Cl DHBd | 0.22 (0.06) | — | 2.00 (0.04) | 9 (2) | 1,650 (80) | 1.2 (0.1) | 5.5 (2.0) | |

| 3′-Cl DHBd | 1.9 (0.3) | 1.5 (0.3) | 27.0 (0.8) | 14.2 (1.8) | 2,290 (190) | 11.8 (1.3) | 6.2 (1.7) | |

| 4-Cl DHBd | 22.0 (2.6) | 2.6 (0.7) | 110 (5) | 4.9 (0.4) | 27,800 (200) | 3.9 (0.2) | 0.18 (0.03) | |

| 5-Cl DHBd | 5.3 (0.6) | — | 7.2 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.1) | 660 (35) | 11.0 (0.8) | 2.1 (0.4) | |

| 3′,5′-DiCl DHB | 0.20 (0.02) | — | 36.0 (0.8) | 180 (18) | 8,330 (1,100) | 4.1 (0.2) | 20.5 (3.1) | |

| 5,3′-DiCl DHB | 0.37 (0.03) | — | 4.9 (0.07) | 13.3 (0.9) | 2,620 (20) | 1.8 (0.2) | 4.9 (0.9) | |

| 2′,6′-DiCl DHBd | 0.145 (0.014) | — | 0.088 (0.004) | 0.61 (0.09) | 49.9 (1.2) | 1.7 (0.1) | 11.7 (1.6) | |

| 4,3′,5′-triC1 DHB | 0.46 (0.046) | 29.9 (3.5) | 25.2 (0.8) | 54.5 (4) | 6,150 (150) | 4.1 (0.4) | 8.9 (1.8) | |

| DHBDP6-III | DHBd | 17.0 (1.9) | — | 17.0 (0.6) | 1.0 (0.1) | 900 (60) | 19.0 (2.0) | 1.1 (0.2) |

| 2′-Cl DHBd | 10.0 (1.0) | — | 5.3 (0.1) | 0.50 (0.04) | 1,990 (160) | 2.7 (0.3) | 0.25 (0.05) | |

| 3′-Cl DHBd | 10.0 (0.7) | — | 14.2 (0.3) | 1.40 (0.08) | 870 (70) | 16.3 (1.7) | 1.6 (0.3) | |

| 4-Cl DHBd | 1.8 (0.2) | — | 4.0 (0.1) | 2.2 (0.2) | 260 (40) | 15.5 (3.0) | 8.6 (2.6) | |

| 5-Cl DHBd | 4.3 (0.6) | — | 6.6 (0.3) | 1.5 (0.2) | 100 (20) | 68.0 (17.1) | 15.8 (6.2) | |

| 3′,5′-DiCl DHB | 3.5 (0.5) | — | 6.9 (0.2) | 2.0 (0.2) | 560 (60) | 11.3 (0.6) | 3.2 (0.6) | |

| 5,3′-DiCl DHB | 1.8 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.4) | 3.6 (0.1) | 2.0 (0.2) | 330 (40) | 9.4 (0.3) | 5.2 (0.7) | |

| 2′,6′-DiCl DHBd | 3.9 (0.4) | — | 0.069 (0.002) | 0.017 (0.001) | 15.0 (0.3) | 5.4 (0.2) | 1.4 (0.1) | |

| 4,3′,5′-TriCl DHB | 0.070 (0.009) | — | 1.9 (0.05) | 28 (3) | 750 (150) | 2.5 (0.5) | 36 (12) | |

| THBDRW1 | DHB | 2.80 (0.35) | —*c | 97.5 (2.6) | 35.0 (7.5) | 59,300 (1,800) | 2.30 (0.01) | 0.80 (0.06) |

| 2′-Cl DHB | 0.11 (0.01) | — | 3.1 (0.1) | 29.0 (3.5) | 9,200 (300) | 0.310 (0.001) | 3.1 (0.4) | |

| 3′-Cl DHB | 0.56 (0.06) | — | 30.5 (0.9) | 55.0 (7.5) | 8,800 (1,100) | 5.00 (0.05) | 8.9 (1.8) | |

| 4-Cl DHB | 5.6 (0.8) | — | 2.9 (0.1) | 0.52 (0.09) | 6,800 (240) | 0.670 (0.001) | 0.11 (0.02) | |

| 5-Cl DHB | 0.17 (0.01) | — | 5.0 (0.1) | 30.0 (2.4) | 5,500 (150) | 1.33 (0.01) | 7.8 (0.9) | |

| 3′,5′-DiCl DHB | 0.120 (0.003) | — | 17.5 (0.1) | 150 (5) | 960 (60) | 18 (1) | 160 (13) | |

| 5,3′-DiCl DHB | 0.046 (0.016) | — | 3.7 (0.7) | 80 (30) | 710 (200) | 5.2 (0.5) | 110 (40) | |

| 2′,6′-DiCl DHB | 0.150 (0.006) | — | 0.00090 (0.00002) | 0.006 (0.002) | 9.4 (0.2) | 0.120 (0.004) | 2.4 (0.2) | |

| 4,3′,5′-TriCl DHB | 0.13 (0.02) | — | 0.190 (0.005) | 1.5 (0.2) | 74 (3) | 2.60 (0.03) | 20 (3) |

The values in parentheses represent standard errors.

—, no inhibition was observed.

—*, KiA estimated at 1 mM.

Data taken from reference 37.

The suitability of Cl DHBs as substrates for the dioxygenases can also be evaluated from the partition ratios. The latter is a measure of the average number of DHB molecules cleaved per enzyme molecule prior to oxidative inactivation of the latter. In principle, an enzyme should have a higher partition ratio for substrates that it has evolved to transform. As with the specificity constants, no consistent trend is immediately evident in the partition ratios or susceptibility to inactivation (j3app/KmAapp): each enzyme had a distinct pattern of susceptibility to inactivation by the different DHBs. However, the partition ratios of three of the enzymes (DHBDLB400, DHBDP6-I, and THBDRW1) were highest for DHB.

Although DHBDP6-III generally cleaved DHBs more slowly than the other three enzymes, this enzyme seemed best suited to the degradation of PCBs. More particularly, this enzyme showed a greater specificity for most of the tested Cl DHBs than for unchlorinated DHB. Most strikingly, the apparent specificity of DHBDP6-III for 4,3′5′-triCl DHB was 28 times higher than that for DHB. Similarly, the partition coefficients of the enzyme for many Cl DHBs was comparable to that for DHB.

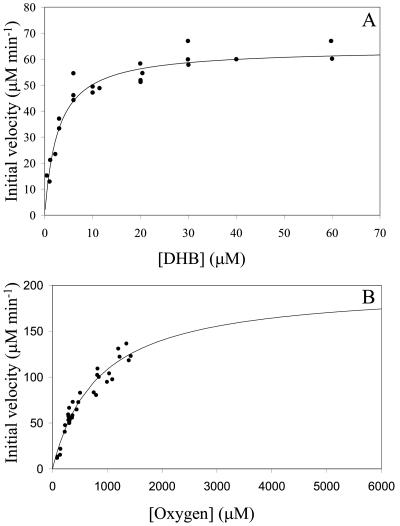

THBDRW1 had a good specificity for 2′-Cl DHB and had a relatively high partition coefficient in the presence of this substrate. This is consistent with the enzyme's physiological role in the degradation of dibenzofuran. Moreover, the specificity constant of THBDRW1 for several Cl DHBs was either very similar to or higher than that of unchlorinated DHB (3′,5′-diCl DHB > 3′-Cl DHB > DHB ∼ 2′-Cl DHB). It was therefore somewhat surprising that, among the tested enzymes, THBDRW1 cleaved 2′,6′-diCl DHB the least efficiently and had the lowest partition coefficient in the presence of this compound. Interestingly, no substrate inhibition was observed with any Cl DHBs even at a concentration of 3,300 times Kmapp in the case of 2′-Cl DHB. Some substrate inhibition was observed in the presence of DHB, as reported by Happe et al. (20), but the KiA could not be reliably evaluated from the present data (Fig. 2A). Finally, the enzyme's KmO2 in the presence of DHB was 0.8 ± 0.1 mM (Fig. 2B), which is comparable to those reported for DHBDLB400 (1.2 ± 0.2 mM) and DHBDP6-I (0.25 ± 0.02 mM).

FIG. 2.

Steady-state cleavage of DHB by THBDRW1. (A) Dependence of initial velocity on the concentration of DHB in air-saturated buffer. The line represents a best fit of the Michaelis-Menten equation to the data. The fitted parameters are Kmapp = 2.8 ± 0.4 μM and V = 64 ± 2 μM/min. (B) Dependence of initial velocity on the concentration of O2 with 100 μM DHB. The line represents a best fit of the Michaelis-Menten equation to the data. The fitted parameters are KmO2app = 830 ± 100 μM and V = 200 ± 20 μM/min. All experiments were performed using air-saturated 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, at 25°C. Initial velocities obtained on different days were normalized according to the amount of enzyme used in the assay.

DISCUSSION

The data presented in this study expand on the published reactivities of DHBDLB400, DHBDP6-I, and DHBDP6-III for monoCl DHBs and 2′,6′-diCl DHB (37) and provide insight into the reactivity of THBDRW1, whose physiological substrate, 2,2′,3-THB, is structurally similar to 2′,6′-diCl DHB, a recalcitrant PCB metabolite. The four studied enzymes possessed markedly different reactivities towards PCB metabolites. Nevertheless, the data clearly indicate that each enzyme has a greater substrate specificity for at least one Cl DHB than for unchlorinated DHB. As the data set is not exhaustive, it is likely that these enzymes cleave other polychlorinated DHBs with greater specificity as well. In most cases, chloro substituents had similar effects on the kinetic parameters of the different enzymes for DHB. Nevertheless, the effect of multiple chloro substituents on the reactivity could not be easily predicted from the reactivity of the corresponding monoCl DHBs. For example, the apparent specificity of DHBDP6-III for 4,3′,5′-triCl DHB was over 12 times higher than any for the corresponding monoCl and diCl DHBs, and its Km was 25 to 50 times lower.

Overall, the present data agree reasonably well with steady-state kinetic parameters and relative activities reported by McKay et al. (24). Both studies evaluated the steady-state kinetic parameters of DHBDP6-I and -III for DHB and 2′- and 3′-Cl DHB. The main differences are in the kcatapp, kAapp, and partition coefficients of DHBDP6-I: in the present study they are up to an order of magnitude higher than previously reported. These effects are presumably due to the low iron content, as reported by the authors, of the enzyme used previously. McKay et al. also reported relative activities of five enzymes at 100 μM concentrations of various DHBs, by normalizing the data to the rate of cleavage of unchlorinated DHB. Accordingly, we calculated relative activities at 100 μM DHB using the steady-state parameters reported in Table 3. For the 15 combinations of enzyme and Cl DHB studied by both groups, the relative activities agreed to within a factor of 3. Considering that McKay et al. isolated Cl DHBs from culture supernatants containing up to 20% unwanted Cl DHBs, this is a surprising degree of agreement. Nevertheless, the true measure of an enzyme's ability to utilize different substrates is the specificity constant (14). In this respect, the relative activities determined at 100 μM substrate do not agree well with relative specificities (kAapp for each Cl DHB normalized to kAapp for DHB), differing by over 2 orders of magnitude in some cases. The correspondence between relative activity and specificity is particularly poor for substrates with low Kms, such as 3′,5′-diCl DHB. Related to this, despite investigating the relative activities of five enzymes for each of 17 DHBs, McKay et al. did not identify a single Cl DHB that is a better substrate for a given enzyme than DHB.

The physiological roles of the single-domain DHBDs in R. globerulus P6, DHBDP6-II and DHBDP6-III, remain unclear. Based on the higher specificity of these enzymes for some Cl DHBs than for unchlorinated DHB, it has been suggested that they may have been recruited by R. globerulus P6 to improve its PCB degradation (24, 37). However, the present results demonstrate that relatively high specificity constants for Cl DHBs are not unique to the single-domain DHBDs. Moreover, the activities of the latter enzymes are relatively low compared to those of the two-domain enzymes. Finally, conditions under which DHBDP6-III is expressed in R. globerulus P6 have yet to be identified (24). It is possible that the primary physiological role of DHBDP6-II and -III is not biphenyl catabolism or PCB transformation. Rhodococcal strains in particular appear to contain large numbers of DHBD-type enzymes, with seven or more reported in each of strains TA421 (23), RHA1 (27), and K37 (34). Although the genes encoding these enzymes have been annotated as bphC genes, recent Northern hybridization analyses in K37 (34) and DNA microarray studies in RHA1 indicate that most of them are not involved in biphenyl degradation (E. R. Gonçalves, H. Hara, D. S. Aeschliman, M. Fukuda, L. D. Eltis, and W. W. Mohn, unpublished data).

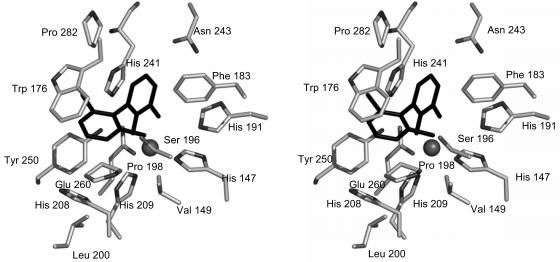

The relatively low Kmapp values of the enzymes for polychlorinated DHBs compared to the monoCl DHBs or even the nonchlorinated DHB suggest that the substrate-binding pockets of these enzymes can readily accommodate the chloro substituents. The structure of a DHBDLB400:DHB binary complex revealed that the substrate-binding pocket of this enzyme is lined with hydrophobic residues (19). With the exception of the catalytic residues, Phe187, Asn243, and Pro280 line the proximal part of the pocket around the hydroxylated ring of DHB, and Val148, Met175, Ala200, Phe202, and His209 line the distal part of the pocket around the nonhydroxylated ring. Structural modeling and sequence alignments (13) suggest that the respective substrate-binding pockets of the other enzymes are lined with similar types of residues. For example, a model of the THBDRW1:2′,6′-diCl DHB binary complex indicates that Phe183, Asn243, and Pro282 line the proximal part of the pocket and Val149, Met176, Ser196, Pro198, and His208 line the distal part of the pocket (Fig. 3). In the crystallographic and modeled structures, the ring carbons of the bound substrate are relatively unencumbered: no residue approaches to within 3.25 Å of C-4, C-5, and C-6 of the bound DHB in the DHBDLB400:DHB complex. C-3′, C-4′, and C-5′ of the distal ring are even less sterically hindered, being oriented towards the opening of the active site. Overall, the architecture of the substrate-binding pocket of DHBDs and the sequence data are consistent with the kinetic data.

FIG. 3.

Stereo view of the modeled active site of THBDRW1 bound to 2′,6′-diCl DHB. The residues lining the substrate pocket and the bound DHB are represented in gray and black, respectively. The ligands of the ferrous iron (shown as a sphere) are His147, His209, and Glu260. The conserved catalytic residues are His191, His241, and Tyr250.

The failure of four evolutionarily divergent DHBDs to significantly cleave 2′,6′-diCl DHB (37) suggests that such an activity is rare in nature and may be inherent in the binding of this compound to the active-site iron. In all DHBD:DHB structures determined to date, the distal ring is twisted with respect to the proximal ring. In the structures of the 2′-Cl DHB and 2′,6′-diCl DHB complexes of DHBDLB400, a chloro substituent is positioned such that it abuts the dioxygen-binding pocket and may hinder proposed attack of an iron-superoxo species at C-2 (11). Nevertheless, it might be possible to develop 2′,6′-diCl DHB cleavage activity by using in vitro evolution. A critical parameter in the success of in vitro evolution is the enzyme(s) selected as parent(s). THBDRW1 and DHBDP6-I might be good starting points due to their relatively low inactivation constant (j3app) and high kcatapp with 2′6′-diCl DHB, respectively. Alternatively, DHBDP6-III might be a better candidate, as it appears to be poorly evolved for DHBs. In particular, this enzyme possesses a relatively low, broad specificity for Cl DHBs and relatively high Km for 2′,6′-diCl DHB. Interestingly, we have recently observed that DoxG, an extradiol enzyme involved in naphthalene catabolism and having a poor specificity for DHB, cleaves 2′,6′-diCl DHB more efficiently than any of the enzymes in the present study (P. D. Fortin and L. D. Eltis, unpublished data).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an Operating and Strategic grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). P.D.F. was the recipient of FCAR and NSERC postgraduate scholarships.

We thank Jeffrey T. Bolin for critically reading the manuscript, Frédéric Vaillancourt for helpful discussions, and Michela Bertero for valuable assistance with the structural modeling. We thank Victor Snieckus and Frank Reifenrath for the synthesis of Cl DHBs and Marvin Hsiao for assistance with some of the experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abramowicz, D. A. 1990. Aerobic and anaerobic biodegradation of PCBs: a review. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 10:241-251. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asturias, J. A., L. D. Eltis, M. Prucha, and K. N. Timmis. 1994. Analysis of three 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenases found in Rhodococcus globerulus P6. J. Biol. Chem. 269:7807-7815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asturias, J. A., and K. N. Timmis. 1993. Three different 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl-1,2-dioxygenase genes in the gram-positive polychlorobiphenyl-degrading bacterium Rhodococcus globerulus P6. J. Bacteriol. 175:4631-4640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl. 2000. Current protocols in molecular biology. J. Wiley & Sons Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 5.Barriault, D., M. Vedadi, J. Powlowski, and M. Sylvestre. 1999. cis-2,3-Dihydro-2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dehydrogenase and cis-1,2-dihydro-1,2-dihydroxynaphthalene dehydrogenase catalyze dehydrogenation of the same range of substrates. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 260:181-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barriault, D., M. M. Plante, and M. Sylvestre. 2002. Family shuffling of a targeted bphA region to engineer biphenyl dioxygenase. J. Bacteriol. 184:3794-3800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bopp, L. H. 1986. Degradation of highly chlorinated PCBs by Pseudomonas strain LB400. J. Ind. Microbiol. 1:23-29. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruhlmann, F., and W. Chen. 1999. Transformation of polychlorinated biphenyls by a novel BphA variant through the meta-cleavage pathway. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 179:203-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cornish-Bowden, A. 1995. Analysis of enzyme kinetic data. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y.

- 11.Dai, S., F. H. Vaillancourt, H. Maaroufi, N. M. Drouin, D. B. Neau, V. Snieckus, J. T. Bolin, and L. D. Eltis. 2002. Identification and analysis of a bottleneck in PCB biodegradation. Nat. Struct. Biol. 9:934-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Lorenzo, V., L. D. Eltis, B. Kessler, and K. N. Timmis. 1993. Analysis of Pseudomonas gene products using lacIq/Ptrp-lac plasmids and transposons that confer conditional phenotypes. Gene 123:17-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eltis, L. D., and J. T. Bolin. 1996. Evolutionary relationships among extradiol dioxygenases. J. Bacteriol. 178:5930-5937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fersht, A. R. 1985. Enzyme structure and mechanism. W. H. Freeman & Co., New York, N.Y.

- 15.Furukawa, K., H. Suenaga, and M. Goto. 2004. Biphenyl dioxygenases: functional versatilities and directed evolution. J. Bacteriol. 186:5189-5196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furukawa, K. 2000. Biochemical and genetic bases of microbial degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs). J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 46:283-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Furukawa, K., N. Tomizuka, and A. Kamibayashi. 1979. Effect of chlorine substitution on the bacterial metabolism of various polychlorinated biphenyls. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 38:301-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haigler, B. E., and D. T. Gibson. 1990. Purification and properties of NADH-ferredoxinNAP reductase, a component of naphthalene dioxygenase from Pseudomonas sp. strain NCIB 9816. J. Bacteriol. 172:457-464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han, S., L. D. Eltis, K. N. Timmis, S. W. Muchmore, and J. T. Bolin. 1995. Crystal structure of the biphenyl-cleaving extradiol dioxygenase from a PCB-degrading pseudomonad. Science 270:976-980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Happe, B., L. D. Eltis, H. Poth, R. Hedderich, and K. N. Timmis. 1993. Characterization of 2,2′,3-trihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase, an extradiol dioxygenase from the dibenzofuran- and dibenzo-p-dioxin-degrading bacterium Sphingomonas sp. strain RW1. J. Bacteriol. 175:7313-7320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herrero, M., V. de Lorenzo, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:6557-6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohler, H.-P. E., D. Kohler-Staub, and D. D. Focht. 1988. Cometabolism of polychlorinated biphenyls: enhanced transformation of Aroclor 1254 by growing bacterial cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:1940-1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maeda, M., S. Y. Chung, E. Song, and T. Kudo. 1995. Multiple genes encoding 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenase in the gram-positive polychlorinated biphenyl-degrading bacterium Rhodococcus erythropolis TA421, isolated from a termite ecosystem. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:549-555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McKay, D. B., M. Prucha, W. Reineke, K. N. Timmis, and D. H. Pieper. 2003. Substrate specificity and expression of three 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenases from Rhodococcus globerulus strain P6. J. Bacteriol. 185:2944-2951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nerdinger, S., C. Kendall, R. Marchhart, P. Riebel, M. R. Johnson, C.-F. Yin, L. D. Eltis, and V. Snieckus. 1999. Directed ortho-metalation and Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling connections: regiospecific synthesis of all isomeric chlorodihydroxybiphenyls for microbial degradation studies of PCBs. Chem. Commun. 1999:2259-2260. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Notredame, C., D. Higgins, and J. Heringa. 2000. T-Coffee: A novel method for multiple sequence alignments. J. Mol. Biol. 302:205-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakai, M., E. Masai, H. Asami, K. Sugiyama, K. Kimbara, and M. Fukuda. 2002. Diversity of 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase genes in a strong PCB degrader, Rhodococcus sp. strain RHA1. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 93:421-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sali, A., and T. L. Blundell. 1993. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234:779-815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seah, S. Y. K., G. Labbé, S. R. Kaschabek, F. Reifenrath, W. Reineke, and L. D. Eltis. 2001. Comparative specificities of two evolutionarily divergent hydrolases involved in microbial degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls. J. Bacteriol. 183:1511-1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seah, S. Y. K., G. Labbé, S. Nerdinger, M. R. Johnson, V. Snieckus, and L. D. Eltis. 2000. Identification of a serine hydrolase as a key determinant in the microbial degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls. J. Biol. Chem. 275:15701-15708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seeger, M., K. N. Timmis, and B. Hofer. 1995. Conversion of chlorobiphenyls into phenylhexadienoates and benzoates by the enzymes of the upper pathway for polychlorobiphenyl degradation encoded by the bph locus of Pseudomonas sp. strain LB400. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:2654-2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suenaga, H., T. Watanabe, M. Sato, Ngadiman, and K. Furukawa. 2002. Alteration of regiospecificity in biphenyl dioxygenase by active-site engineering. J. Bacteriol. 184:3682-3688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tabor, S., and C. C. Richardson. 1985. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:1074-1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taguchi, K., M. Motoyama, and T. Kudo. 2004. Multiplicity of 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl dioxygenase genes in the Gram-positive polychlorinated biphenyl degrading bacterium Rhodococcus rhodochrous K37. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 68:787-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaillancourt, F. H., S. Han, P. D. Fortin, J. T. Bolin, and L. D. Eltis. 1998. Molecular basis for the stabilization and inhibition of 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenase by t-butanol. J. Biol. Chem. 273:34887-34895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaillancourt, F. H., G. Labbé, N. M. Drouin, P. D. Fortin, and L. D. Eltis. 2002. The mechanism-based inactivation of 2,3-dihydroxybiphenyl 1,2-dioxygenase by catecholic substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 277:2019-2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vaillancourt, F. H., M. A. Haro, N. M. Drouin, Z. Karim, H. Maaroufi, and L. D. Eltis. 2003. Characterization of extradiol dioxygenases from a polychlorinated biphenyl-degrading strain that possess higher specificities for chlorinated metabolites. J. Bacteriol. 185:1253-1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]