The diagnostic differentiation of limb dystonia and parkinsonism in young adults represents a challenge for physicians because both Segawa’s disease (DYT5a), the classic form of dopa-responsive dystonia (DRD), and young-onset Parkinson’s disease (PD) share similar clinical presentations and, initially, both respond excellently to levodopa. In the early stage, clinical observations are often insufficient for differentiation, and, therefore, physicians increasingly rely on diagnostic strategies that incorporate clinical, genetic, biochemical, and brain imaging tests. However, one single test is insufficient. For example, the presence of a GCH1 mutation alone does not confirm a diagnosis of DRD because DRD is a syndrome that encompasses an array of clinically and genetically heterogeneous disorders and is not exclusive to Segawa’s disease [1]. Moreover, recent evidence suggests that rare mutations in GCH1 can also lead to a PD phenotype that is associated with abnormal presynaptic dopaminergic imaging [2]. In this case report, we emphasize the need for well-planned diagnostic and management strategies in this patient group.

A previously healthy 35-year-old woman was referred to our movement disorders clinic for a diagnostic confirmation of DRD following a one-year history of abnormal posture of the left foot. Her symptoms developed gradually and she denied the presence of diurnal fluctuations. Although her symptoms responded well to levodopa (50 mg three times daily), upon examination, a mild degree of left foot dystonic inversion remained during a fast walk that was associated with mild left finger bradykinesia. MRI of her brain and cervical spinal cord were unremarkable. Despite her positive response to levodopa, she reported increased left foot dystonia when tired and before her next levodopa dose. Her 73-year-old mother and 60-year-old uncle had undiagnosed gait difficulties and her grandfather was diagnosed with parkinsonism at the age of 80.

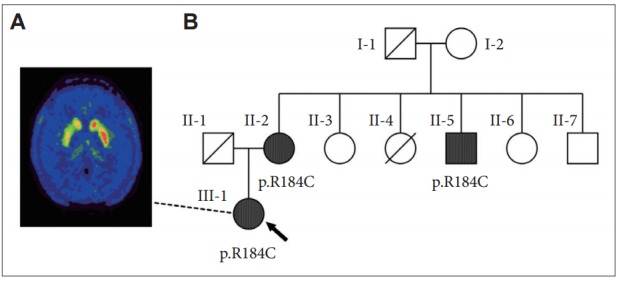

In clinical practice, the diagnosis of DRD is similar to that of Segawa’s disease (DYT5a), implying a non-degenerative biochemical defect in dopamine synthesis as a result of a deficiency in GTP cyclohydrolase 1, which is encoded by the GCH1 gene [3]. In this disorder, patients are expected to experience sustained improvement with low-dose levodopa without further motor complications. Our patient responded well to levodopa, but continued to display mild foot dystonia. This may be due to diurnal fluctuation, a feature observed in 50% of Segawa’s patients. The onset of this symptom after levodopa therapy, along with a mild decline in therapeutic response, suggested that an alternative diagnosis may be in order. Next generation sequencing was performed and revealed a pathogenic heterozygous variant of the GCH1 gene (c.550C>T; p.R184C) without evidence of other mutations responsible for other familial causes of parkinsonism, including PARK2, PARK7, PINK1, SNCA, LRRK2, ATP13A2, ATXN2, ATXN3, and TPB. The 18F-dihydroxyphenylalanine positron emission tomography ([18F]DOPA-PET) of the patient’s brain revealed decreased [18F]DOPA uptake in the right putamen with more preservation in the caudate (Figure 1A). CSF studies for biopterin and neopterin were not performed.

Figure 1.

Patientʼs [18F]DOPA-PET imaging and her pedigree. A: [18F]DOPAPET of our patient (III-1) showing decreased [18F]DOPA uptake in the right caudate and putamen, indicating a degenerative etiology. B: Pedigree showing two additional individuals with the same pathogenic heterozygous GCH1 variant (R184C): the patient (arrow), her 73-year-old mother (II-2) who complained of slowing gait beginning one year ago, and her 60-year-old uncle (II-5) who has a history of alcoholism and has had ataxia for two years. Individual II-4 died from perinatal pneumonia. Diagnosed with Parkinsonism at 80 years old, her grandfather (I-1) had received levodopa for two years before dying of aspiration pneumonia. None of the family members had dystonia. [18F]DOPA-PET: 18F-dihydroxyphenylalanine positron emission tomography.

GCH1 mutations are not exclusive to Segawa’s disease, and specific variants have been identified in patients with the PD phenotype, suggesting a degenerative etiology. Indeed, variant R184C was reported to cause DRD in a 25-year-old Ashkenazic female whose family had the PD phenotype, although no additional clinical details were available [4]. Another report identified variant R184H, the same codon as our patient, in a 39-year-old woman with a similar clinical presentation and abnormal [18F]DOPA-PET imaging [5]. Regarding our patient, two members of her family with gait instability were later found to harbor the same mutation (Figure 1B). Therefore, it is likely that our patient has familial PD due to a pathogenic GCH1 mutation.

Establishing levodopa responsiveness in this clinical setting may suffice for a clinical conclusion of DRD, but physicians should not be satisfied with this syndromic diagnosis. DRD is a syndrome with an etiology that can be either biochemical or degenerative [1]. Early identification of the root cause is important because the long-term management differs between the two etiologies. The patient’s age at onset may aid in differentiation because biochemical defects commonly become evident in childhood, but degenerative causes are more commonly evident in adulthood. If parkinsonian features are observed, particularly in adult-onset cases, functional imaging to determine the presence of nigrostriatal denervation may be necessary [6]. Physicians should also check for specific GCH1 variants because some variants are associated with a risk of PD at a reported odds ratio of 7.5 [2]. If a degenerative cause is likely, physicians should exercise careful consideration when recommending levodopa in this patient group because these patients are at a high risk of developing motor and non-motor fluctuations, similar to young-onset PD patients.

As shown in our case study, conducting further investigations is essential to achieving a definite diagnosis in patients with a clinical syndromic diagnosis of DRD. Certain clinical red flags, such as adult-onset, parkinsonian features, and non-sustained response to levodopa should prompt physicians to proceed with genetic, biochemical and functional dopaminergic imaging or refer such a case to specialist centers. Although they were not performed in our case, CSF studies for homovanillic acid, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, biopterin and neopterin, as well as a blood test for phenylalanine, may be tools that can help characterize different forms of enzymatic deficiencies with identical clinical presentations [1]. Further studies are needed to determine the genotype-phenotype associations and the long-term natural history of these disorders.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Dr. Objoon Trachoo, Division of Genetics, Department of Medicine, Ramathibodi Hospital for genetic analysis and Dr. Supatporn Tepmongkol, Division of Nuclear Medicine, Department of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University for the interpretation of [18F]DOPA PET imaging.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wijemanne S, Jankovic J. Dopa-responsive dystonia--clinical and genetic heterogeneity. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:414–424. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mencacci NE, Isaias IU, Reich MM, Ganos C, Plagnol V, Polke JM, et al. Parkinson’s disease in GTP cyclohydrolase 1 mutation carriers. Brain. 2014;137(Pt 9):2480–2492. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bandmann O, Valente EM, Holmans P, Surtees RA, Walters JH, Wevers RA, et al. Dopa-responsive dystonia: a clinical and molecular genetic study. Ann Neurol. 1998;44:649–656. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hagenah J, Saunders-Pullman R, Hedrich K, Kabakci K, Habermann K, Wiegers K, et al. High mutation rate in dopa-responsive dystonia: detection with comprehensive GCHI screening. Neurology. 2005;64:908–911. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000152839.50258.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kikuchi A, Takeda A, Fujihara K, Kimpara T, Shiga Y, Tanji H, et al. Arg(184)His mutant GTP cyclohydrolase I, causing recessive hyperphenylalaninemia, is responsible for doparesponsive dystonia with parkinsonism: a case report. Mov Disord. 2004;19:590–593. doi: 10.1002/mds.10712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trender-Gerhard I, Sweeney MG, Schwingenschuh P, Mir P, Edwards MJ, Gerhard A, et al. Autosomal-dominant GTPCH1-deficient DRD: clinical characteristics and long-term outcome of 34 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:839–845. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.155861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]