In this study, Liang et al. investigate the molecular mechanisms by which SUMO (small ubiquitin-like modifier) contributes to post-translational modifications. Their findings demonstrate how the opposing actions of a localized SUMO isopeptidase and a SUMO targeted ubiquitin ligase (STUbL), Slx5:Slx8, regulate rDNA silencing by controlling the abundance of a key rDNA silencing protein, Tof2.

Keywords: sumoylation, desumoylation, STUbL, monopolin, cohibin, rDNA silencing, RENT complex

Abstract

Post-translational modification by SUMO (small ubiquitin-like modifier) plays important but still poorly understood regulatory roles in eukaryotic cells, including as a signal for ubiquitination by SUMO targeted ubiquitin ligases (STUbLs). Here, we delineate the molecular mechanisms for SUMO-dependent control of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) silencing through the opposing actions of a STUbL (Slx5:Slx8) and a SUMO isopeptidase (Ulp2). We identify a conserved region in the Ulp2 C terminus that mediates its specificity for rDNA-associated proteins and show that this region binds directly to the rDNA-associated protein Csm1. Two crystal structures show that Csm1 interacts with Ulp2 and one of its substrates, the rDNA silencing protein Tof2, through adjacent conserved interfaces in its C-terminal domain. Disrupting Csm1's interaction with either Ulp2 or Tof2 dramatically reduces rDNA silencing and causes a marked drop in Tof2 abundance, suggesting that Ulp2 promotes rDNA silencing by opposing STUbL-mediated degradation of silencing proteins. Tof2 abundance is rescued by deletion of the STUbL SLX5 or disruption of its SUMO-interacting motifs, confirming that Tof2 is targeted for degradation in a SUMO- and STUbL-dependent manner. Overall, our results demonstrate how the opposing actions of a localized SUMO isopeptidase and a STUbL regulate rDNA silencing by controlling the abundance of a key rDNA silencing protein, Tof2.

Protein sumoylation regulates a variety of nuclear processes, including gene transcription, nuclear transport, and DNA metabolism, in eukaryotic cells (Johnson 2004; Gareau and Lima 2010). Similarly to ubiquitin, SUMO (small ubiquitin-like modifier) is attached to lysine residues of target proteins via an enzymatic cascade consisting of an E1-activating enzyme, an E2-conjugating enzyme, and one of several E3 ligases (Johnson and Gupta 2001; Zhao and Blobel 2005; Reindle et al. 2006; Albuquerque et al. 2013). Counteracting the sumoylation machinery are SUMO-specific isopeptidases, which cleave SUMO off its target proteins (Li and Hochstrasser 1999, 2000). Together, these enzymes maintain sumoylation homeostasis and responsiveness to a variety of environmental stimuli (Zhou et al. 2004; Cremona et al. 2012). While much has been learned about the identities of sumoylation and desumoylation enzymes as well as their substrates, relatively little is known about how their activities are controlled in different subcellular compartments and on specific substrates.

The identification of a family of SUMO targeted ubiquitin ligases (STUbLs) has demonstrated how sumoylation, particularly polysumoylation, can act as a protein degradation signal (Prudden et al. 2007; Sun et al. 2007), and several cases of such regulation have been reported (Mukhopadhyay et al. 2010; Nie and Boddy 2015). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the STUbL Slx5:Slx8 has been shown to preferentially target polysumoylated substrates in vitro, with this activity directed by at least four SUMO-interacting motifs (SIMs) in Slx5 (Xie et al. 2007, 2010). In vivo, Slx5:Slx8 has been shown to target several mutant or overexpressed proteins for degradation, including a temperature-sensitive mutant of Mot1 (Wang and Prelich 2009) and overexpressed Cse4 (Ohkuni et al. 2016). While these cases point to a role for sumoylation and STUbL activity in protein quality control and homeostasis in mutant situations, direct evidence for their regulation of a normally expressed wild-type protein in S. cerevisiae has so far been elusive.

One well-established function of sumoylation in S. cerevisiae is in the maintenance and regulation of the ribosomal DNA (rDNA) repeats, an array of ∼100–200 copies of a 9.1-kb unit coding for the 5S and 35S ribosomal RNAs (Fig. 1A; Schweizer et al. 1969; Rubin and Sulston 1973). The rDNA repeats are tightly regulated to minimize illegitimate recombination between repeats (which can result in copy number changes or generate extrachromosomal DNA circles) and to silence transcription by RNA polymerase II (Elion and Warner 1986). The Sir2 histone deacetylase and its binding partners, Net1 and Cdc14, make up a key rDNA silencing complex termed RENT (regulator of nucleolar silencing and telophase exit) (Shou et al. 1999; Straight et al. 1999). The RENT complex and Tof2, a paralog of Net1, are recruited to rDNA through Fob1, which specifically binds a “replication fork block” sequence in each rDNA repeat (Huang and Moazed 2003). Also associated with RENT is a complex (sometimes termed “cohibin”) comprising Csm1 and Lrs4, which is necessary for rDNA silencing and also mediates localization of the rDNA to the nuclear periphery (Huang et al. 2006; Mekhail et al. 2008). Both functions of the Csm1:Lrs4 complex depend on the direct binding of Csm1 to the RENT-associated Tof2 protein (Huang et al. 2006; Corbett et al. 2010). Thus, a complex network of protein–protein interactions plus the deacetylase activity of Sir2 all contribute to maintenance of rDNA copy number and rDNA silencing.

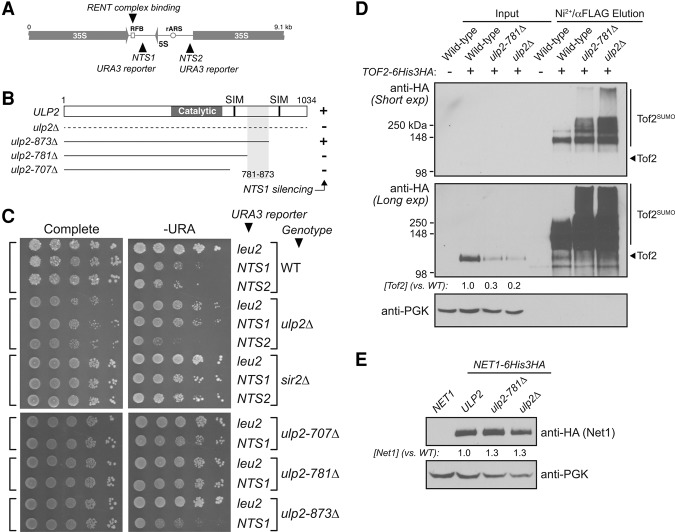

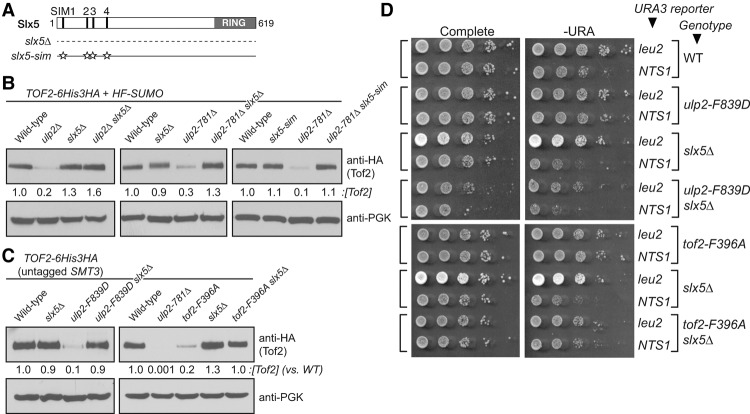

Figure 1.

The Ulp2 C-terminal domain is required for rDNA silencing and nucleolar protein desumoylation. (A) Schematic of a single rDNA repeat in S. cerevisiae. The locations of the 35S and 5S rRNA genes, the replication fork block (RFB) sequence, and the origin of replication (rARS) are shown. Insertion sites for the mURA3 reporter gene in nontranscribed sequences NTS1 and NTS2 are indicated. (B) Schematic of Ulp2 showing the catalytic domain (residues 456–674) and two predicted SIMs (IQII725–728 and VNLI931–934). Three C-terminal truncation mutants (ending at residues 707, 781, and 873) were tested for rDNA silencing (shown in C). The region critical for silencing at NTS1 (residues 781–873) is shaded gray. (C, top) The effect of ulp2Δ (NTS1-specific) and sir2Δ (NTS1 and NTS2) mutations on rDNA silencing. (Bottom) The effect of ulp2 C-terminal truncations on rDNA silencing at NTS1. See Supplemental Figure S1C for the effects on silencing at NTS2. (D) The ulp2Δ and ulp2-781Δ mutants cause both decreased abundance and increased sumoylation of Tof2. Tof2 abundance (input lanes only) was estimated from densitometry of original scanned film images, corrected against PGK loading controls, and then expressed as a ratio compared with wild-type levels. Equivalent analyses were performed for Figures 2 and 5–7. (E) Western blot showing Net1 abundance in ulp2Δ and ulp2-781Δ mutants.

Work from several laboratories, including our own, has indicated that the rDNA maintenance network described above is regulated by sumoylation and particularly through opposing activities of a SUMO isopeptidase, Ulp2, and the STUbL Slx5:Slx8. First, several key rDNA silencing proteins, including Net1, Cdc14, and Tof2, have been shown to be sumoylated (Reindle et al. 2006; Cremona et al. 2012; Albuquerque et al. 2013; Srikumar et al. 2013; de Albuquerque et al. 2016; Gillies et al. 2016). These proteins—plus distinct sets of proteins associated with centromeres and origins of DNA replication—show dramatically increased sumoylation in a ulp2Δ mutant, demonstrating that they are Ulp2 substrates (de Albuquerque et al. 2016). Ulp2 preferentially localizes to the nucleolus and interacts with Csm1, suggesting that Ulp2 specificity may be regulated at least in part by localization (Srikumar et al. 2013). Functionally, rDNA copy number is affected by mutants of either SUMO E3 ligases (Takahashi et al. 2008) or Ulp2 (Srikumar et al. 2013), demonstrating a direct role for sumoylation in rDNA maintenance. Finally, mutation of ulp2 causes a dramatic reduction in the levels of both Net1 and Tof2 associated with the rDNA as measured by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) (Gillies et al. 2016). A further mutation of slx5 rescues Net1/Tof2 rDNA association, suggesting that Ulp2's desumoylation activity stabilizes rDNA silencing complexes against Slx5-mediated degradation (Gillies et al. 2016). Importantly, however, effects on overall abundance of rDNA silencing proteins have not been demonstrated, leaving open the question of whether Ulp2 and Slx5:Slx8 act through protein stabilization/degradation or an alternate mechanism.

While the above data paint a compelling picture of Ulp2 and Slx5:Slx8 playing antagonistic roles in rDNA maintenance, key aspects of this picture remain unresolved. First, as Ulp2 remains largely uncharacterized beyond its catalytic domain, the molecular mechanisms of its nucleolar recruitment remain unknown. Furthermore, it is not known whether Ulp2's specificity for its other substrates at centromeres and DNA replication origins is mediated by a similar localization mechanism. Finally, as mentioned above, there remains no direct evidence that ulp2 or slx5 mutants affect the overall abundance of any rDNA silencing protein. Here, we resolve these questions by outlining in detail the molecular mechanisms of Ulp2 recruitment to rDNA and of the opposing actions of Ulp2 and Slx5–Slx8 at the rDNA. We show that ulp2 mutants are defective in rDNA silencing and that this activity is mediated by a conserved region in the previously uncharacterized Ulp2 C terminus that interacts with Csm1. A crystal structure of the Ulp2:Csm1 complex reveals that Ulp2 binds Csm1 equivalently to the monopolin complex subunit Mam1. A second crystal structure reveals that Csm1 can bind Ulp2 and Tof2 simultaneously, thereby mediating the juxtaposition of enzyme (Ulp2) and substrate (Tof2). Disruption of Ulp2–Csm1 binding causes a dramatic increase in polysumoylated Tof2 and a corresponding decrease in Tof2's overall abundance. The loss of Tof2 abundance is rescued by deletion of slx5 or disruption of its four SIMs, demonstrating a direct role for SUMO-directed ubiquitination and degradation by Slx5:Slx8. Together, these findings demonstrate that opposing actions of the SUMO isopeptidase Ulp2 and the STUbL Slx5:Slx8 control the stability of a key rDNA silencing protein, Tof2, via SUMO-dependent degradation.

Results

A conserved region in the Ulp2 C terminus is required for rDNA silencing and nucleolar protein desumoylation

Prior data showing that Ulp2 acts specifically on proteins associated with certain chromosomal loci, including the rDNA, strongly suggest that Ulp2 is recruited directly to these loci (de Albuquerque et al. 2016). To identify regions of Ulp2 important for rDNA localization, we progressively truncated its uncharacterized C-terminal region and examined effects on rDNA maintenance. While reduction of ULP2 expression was shown previously to cause an increase in rDNA copy number (Srikumar et al. 2013), we could not detect changes in rDNA copy number in a ulp2Δ strain (data not shown). We instead turned to an rDNA silencing assay, which measures the ability of cells with mURA3 reporter genes inserted at different loci, including the NTS1 and NTS2 intergenic spacers in the rDNA repeats (Fig. 1A), to grow on medium lacking uracil (Huang and Moazed 2003). As reported previously, deletion of the histone deacetylase Sir2 disrupts silencing of mURA3 reporter genes inserted at both NTS1 and NTS2 (Fig. 1C). In contrast, the ulp2Δ mutation causes a specific loss of silencing at NTS1 (Fig. 1C; Supplemental Fig. 1A–C). NTS1-specific loss of silencing is characteristic of mutants in RENT and RENT-associated proteins, including Fob1, Tof2, Csm1, and Lrs4, all of which associate specifically with NTS1 through Fob1–DNA binding (Huang and Moazed 2003; Huang et al. 2006). We next examined NTS1 silencing in constructs with the ULP2 C terminus progressively truncated at amino acids 873, 781, and 707 (Fig. 1B,C). We found that while silencing is maintained in the ulp2-873Δ strain, it is disrupted in both ulp2-781Δ and ulp2-707Δ (Fig. 1C). Thus, the region between amino acids 781 and 873 of Ulp2 promotes rDNA silencing at NTS1, potentially by mediating its colocalization with RENT and RENT-associated rDNA silencing proteins.

We showed previously that loss of Ulp2 causes a dramatic accumulation of polysumoylated Net1 (de Albuquerque et al. 2016); therefore, we next examined polysumoylation levels of its paralog, Tof2. Using a previously described strain (HF-SUMO) encoding a HIS6-3xFlag-SMT3 gene that allows purification of total sumoylated proteins with a two-step affinity purification procedure (Albuquerque et al. 2013), we found that both the ulp2Δ and ulp2-781Δ mutations cause a significant increase in polysumoylated Tof2 (Fig. 1D, Ni2+/αFlag elution). Both ulp2 mutations also caused a significant decrease in overall Tof2 abundance (Fig. 1D, input). This decrease in abundance suggests that Tof2 polysumoylation may target the protein for STUbL-mediated degradation and that Ulp2 maintains Tof2 abundance by suppressing its polysumoylation. In contrast, while Net1 polysumoylation also increases substantially in the ulp2Δ mutant (de Albuquerque et al. 2016), Net1's overall abundance is not significantly affected in this mutant (Fig. 1E).

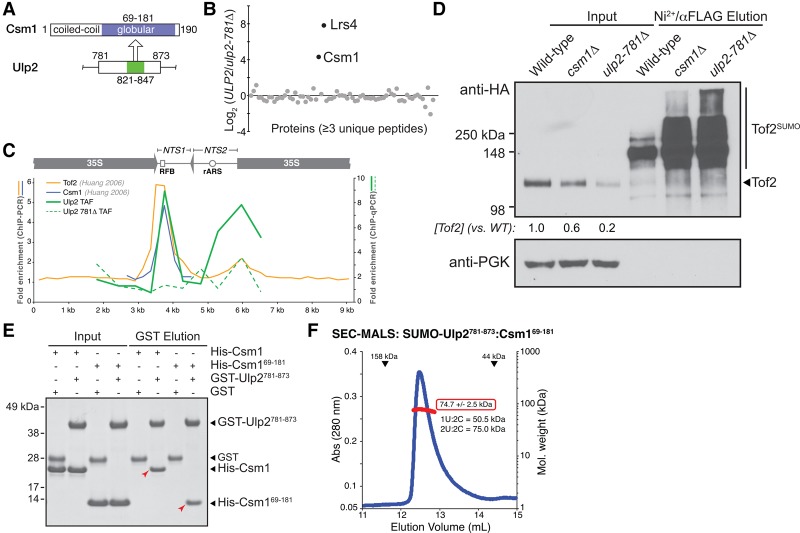

Ulp2781–873 binds the monopolin complex subunit Csm1

Ulp2 was shown recently to interact with Csm1 (Srikumar et al. 2013), which mediates NTS1-specific rDNA silencing through its association with Tof2 (Corbett et al. 2010). One explanation for our findings above is that the Ulp2 C terminus binds Csm1, mediating its recruitment to rDNA-localized RENT complexes (Fig. 2A). Using SILAC (stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture) and quantitative mass spectrometry (MS), we purified Ulp2 from ULP2-TAF (the TAF tag includes protein A, the TEV protease cleavage site, the Flag tag, and His6) (Chen et al. 2007) versus ulp2-781Δ-TAF cells and compared associated proteins between these two samples (Supplemental Fig. 2A). Out of 72 proteins with at least three identified peptides, Csm1 and its binding partner, Lrs4, were the only two that showed a significant decrease upon deletion of the Ulp2 C terminus (Fig. 2B; Supplemental Table 1), indicating that the Ulp2 C terminus mediates the interaction between Ulp2 and Csm1. We next tested whether Ulp2 colocalizes with Csm1 at rDNA using ChIP and quantitative PCR (qPCR). We detected a strong localization of Ulp2 to the previously established Tof2/Csm1/Lrs4-binding site at NTS1 (Huang et al. 2006) as well as a more disperse association with NTS2, and localization to both regions was strongly disrupted in the ulp2-781Δ mutant (Fig. 2C). Finally, we found that the csm1Δ mutation causes an increase in Tof2 polysumoylation and a reduction in its abundance (Fig. 2D), further supporting a direct role for Csm1 in Ulp2 recruitment to rDNA.

Figure 2.

Ulp2 binds the Csm1 C-terminal domain. (A) Schematic of the Ulp2-binding (residues 821–847; green) and Csm1-binding (residues 69–181; blue) regions. (B) Quantitative MS comparison of Ulp2-TAF-associated proteins (Chen et al. 2007) in ULP2-TAF versus ulp2-781Δ-TAF strains. Csm1 and Lrs4 are the only two proteins showing a strong enrichment in wild-type ULP2 cells compared with ulp2-781Δ cells. (C) ChIP-qPCR assay to detect the localization of Ulp2-TAF (solid green line) or Ulp2-781Δ-TAF (dashed green line) to rDNA repeats (average of triplicate samples shown, showing fold enrichment over untagged control). Localizations of Tof2 (orange) and Csm1 (blue) were measured previously by ChIP-PCR, reproduced here for comparison (Huang et al. 2006). (D) Western blot showing that the csm1Δ and ulp2-781Δ mutants have similar effects on Tof2 sumoylation and abundance. (E) GST pull-down assay showing a direct interaction between Csm1 (full-length or isolated C-terminal domain residues 69–181) and GST-Ulp2781–873. The Ulp2–Csm1 interaction is not affected by mutations to the conserved hydrophobic surface on Csm1 that has been implicated in binding Dsn1 and Tof2 (Supplemental Fig. S2A; Corbett et al. 2010). (F) Size exclusion chromatography/multiangle light scattering (SEC-MALS) analysis of SUMO-Ulp2781–873:Csm169–181. Elution volumes of 158- and 44-kDa standards are shown at the top. Calculated molecular weight (red box) indicates a stoichiometry of two Ulp2:two Csm1.

We next tested whether Ulp2 residues 781–873 mediate a direct physical interaction with Csm1. We found that purified GST-Ulp2781–873 robustly binds both full-length Csm1 and its globular C-terminal domain (residues 69–181) (Fig. 2E), which also binds Tof2 and the kinetochore protein Dsn1 (Corbett et al. 2010). Ulp2 binding is not affected by mutations in a conserved hydrophobic surface of Csm1 known to mediate binding to both Tof2 and Dsn1 (Corbett et al. 2010), indicating that a separate surface of Csm1 interacts with Ulp2 (Supplemental Fig. 2B). We finally coexpressed Ulp2781–873 with Csm169–181 and found that they form a stable complex with 2:2 stoichiometry (Fig. 2F).

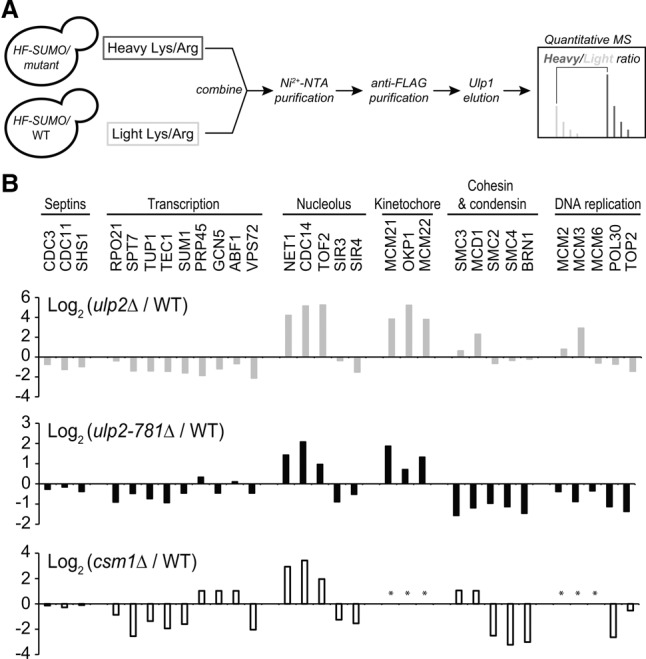

ulp2 and csm1 mutants affect sumoylation of nucleolar and kinetochore proteins

We previously used SILAC and quantitative MS (Fig. 3A) to show that ulp2 deletion causes a dramatic increase in sumoylation of proteins associated with three distinct chromosomal regions, including the rDNA, the centromere, and origins of DNA replication (Fig. 3B, top panel; de Albuquerque et al. 2016). To examine the role of the Ulp2 C-terminal domain in substrate targeting, we used the same analysis to examine global sumoylation levels in ulp2-781Δ and csm1Δ strains. These mutations affect a specific subset of previously identified Ulp2 substrates, including the nucleolar proteins Net1, Tof2, and Cdc14 (in both cases), and the inner kinetochore proteins Mcm21, Okp1, and Mcm22 (for ulp2-781Δ; data for these proteins in csm1Δ did not pass our quality threshold) (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Tables 2, 3). Notably, neither mutant caused an increase in sumoylation of previously identified Ulp2 substrates in the MCM complex, indicating that while Csm1 binding is required for Ulp2 activity on nucleolar and kinetochore substrates, specificity for DNA replication origin-associated proteins is controlled differently. Given our observed effects on both nucleolar and kinetochore proteins, it is interesting to note that Csm1:Lrs4 is known to localize to kinetochores in both mitotic anaphase (Brito et al. 2010) and meiotic prophase (Rabitsch et al. 2003) as part of the monopolin complex. Based on our biochemical and MS data, it seems likely that Csm1 mediates Ulp2 localization to not only the rDNA but kinetochores as well.

Figure 3.

The Ulp2 C-terminal domain and Csm1 contribute to desumoylation of nucleolar and kinetochore proteins. (A) Experimental scheme for SILAC-MS to quantify differential sumoylation in ulp2-781Δ versus wild-type using HIS6-3xFlag-SMT3 (HF-SUMO). (B) Quantitative MS analysis. (Top panel) ulp2Δ versus wild type (gray bars) (de Albuquerque et al. 2016). (Middle panel) ulp2-781Δ versus wild type (black bars). (Bottom panel) csm1Δ versus wild type (black-outlined bars). Positive log2 values indicate proteins whose sumoylation increases in the mutant. Shown is a subset of proteins previously shown by other studies to be sumoylated and/or to be Ulp2 substrates (see Supplemental Tables 2, 3 for a complete list of the modified proteins identified). The asterisk indicates protein not found with at least three unique peptides.

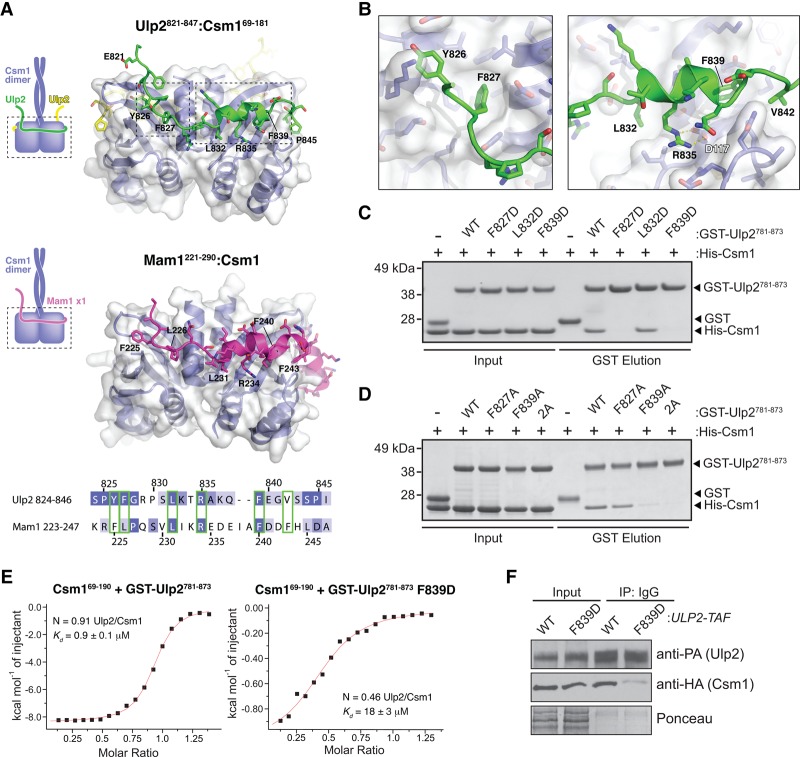

Ulp2781–873 contains a Csm1-binding region similar to Mam1

To identify and characterize the minimal region of Ulp2 necessary for Csm1 binding, we progressively truncated Ulp2 based on sequence conservation and tested for Csm1 binding by coexpression in Escherichia coli (Supplemental Fig. 2C). We next determined a 2.15 Å-resolution X-ray crystal structure of the minimal Ulp2 fragment, residues 821–847, in complex with Csm169–181 (Fig. 4A,B; Supplemental Table 4). In agreement with our biochemical data, the structure shows a Csm1 dimer bound to two copies of Ulp2, each of which wraps around one side of the Csm1 dimer and makes contacts with both Csm1 protomers (Fig. 4A, top panel). Ulp2 buries several conserved residues against Csm1, including Y826 and F827, which insert into a shallow hydrophobic pocket on one Csm1 protomer, and L832, R835, F839, and V842, which contact the dimer-related Csm1 protomer (Fig. 4B). As expected from our binding assays with Csm1 mutants, Ulp2 does not interact with the conserved hydrophobic surface on Csm1 that mediates Tof2/Dsn1 binding. Thus, simultaneous interaction of Csm1 with Ulp2 and Tof2 is likely possible.

Figure 4.

Structural basis for Ulp2 binding to Csm1. (A) The top panel shows the structure of Ulp2821–847 (green) bound to Csm169–181 (blue, white surface). The middle panel shows the structure of Mam1221–290 (magenta) bound to Csm169–181 (blue, white surface). The view is equivalent to the top panel. Shown is a rebuilt version of our original Csm1:Mam1 structure (Protein Data Bank ID 5KTB) with a register error fixed (see the Materials and Methods; Supplemental Fig. 3). The bottom panel is a structure-based sequence alignment of Ulp2 and Mam1, with equivalent Csm1-binding residues boxed in green. (B) Detail views of Ulp2 binding to Csm1 (locations indicated by dotted boxes in the top panel of A). (C,D) GST pull-down assays showing the effects of mutating Ulp2 residues F827, L832, and F839 on its interaction with Csm1. (E) Isothermal titration calorimetry showing binding between Csm169–190 and Ulp2781–873, wild-type versus ulp2-F839D mutant. Fit values for wild type: n = 0.91 ± 0.004; K = 1.07 × 106 ± 7.51 × 104 M−1; ΔH = −8613 ± 51.73 cal/mol; ΔS = −1.49 cal/mol/deg. Fit values for the F839D mutant: n = 0.46 ± 0.02; K = 5.58 × 104 ± 9.68 × 103 M−1; ΔH = −1078 ± 58.39 cal/mol; ΔS = 18.1 cal/mol/deg. (F) Coimmunoprecipitation of Csm1-HA by Ulp2 in ULP2-TAF and ulp2-F839D-TAF strains.

At meiotic kinetochores, Csm1 binds both the kinetochore protein Dsn1 and the monopolin complex subunit Mam1 through adjacent interfaces on its C-terminal globular domain (Corbett and Harrison 2012). Strikingly, the interaction of Ulp2821–847 with Csm1 closely resembles that of Mam1 (Fig. 4A, middle panel). While Mam1 forms a more extensive interface with Csm1 that includes a short C-terminal α helix packing against the Csm1 β sheet, the bulk of Mam1's interface with Csm1 overlays closely with that of Ulp2. A structure-based sequence alignment shows that Mam1 and Ulp2 share limited sequence homology in their Csm1-binding regions, especially in residues that make specific hydrophobic or salt bridge contacts with Csm1 (Fig. 4A, bottom panel). Thus, Csm1 uses a common surface to mediate functionally distinct interactions in the nucleolus (with Ulp2) and the meiotic kinetochore (with Mam1).

To validate our structural findings, we performed a pull-down assay with GST-Ulp2781–873 containing mutations in key hydrophobic residues that interact with Csm1: F827, L832, and F839. While mutation of L832 had no detectable effect, mutation of either F827 or F839 to a negatively charged residue (aspartate) completely disrupted Ulp2 binding to Csm1 (Fig. 4C). Single mutations of these residues to alanine showed a more subtle effect, but mutation of both phenylalanine residues to alanine (2A mutant; F827A/F839A) also completely disrupted binding (Fig. 4D). Using isothermal titration calorimetry, we found that Ulp2781–873 binds Csm1 with a Kd of 0.9 µM and a stoichiometry of approximately one Ulp2 per Csm1 (two Ulp2s per Csm1 dimer). By comparison, the ulp2-F839D mutation causes a 20-fold weakening of the binding affinity of Ulp2781–873 for Csm1 (18 µM) (Fig. 4E). In agreement with these data, we found that the ulp2-F839D mutation strongly reduces the amount of Csm1 associated with Ulp2 in cells when both Csm1 and Ulp2 are expressed at their endogenous levels (Fig. 4F).

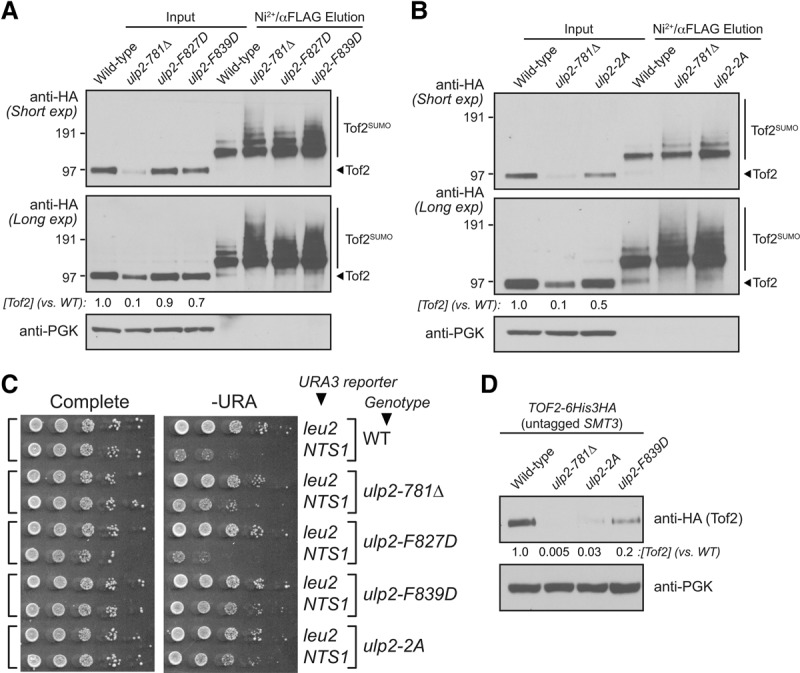

Ulp2–Csm1 binding is required for Tof2 stabilization and rDNA silencing

To verify the biological significance of the Ulp2–Csm1 interface that we identified, we next tested the effects of mutating Ulp2 residues F827 and F839 on Tof2 abundance and sumoylation and on rDNA silencing at NTS1. We tested three Ulp2 mutants that disrupted Csm1 binding in vitro: F827D, F839D, and F827A/F839A (2A). All three point mutants showed a strong increase in Tof2 sumoylation similar to the ulp2-781Δ mutation (Fig. 5A,B). The three mutants had a much more variable effect on Tof2 abundance, with ulp2-F839D and ulp2-2A both showing a modest reduction in Tof2 levels, and ulp2-F827D showing little effect. None of the three point mutants showed as dramatic a reduction in Tof2 levels as in ulp2-781Δ, likely because the point mutants weaken but do not completely eliminate Csm1 binding (Fig. 5A,B). Our observations that overall Tof2 abundance shows more variation than Tof2 sumoylation levels in different mutants is likely due to the turnover of sumoylated Tof2 by desumoylation and/or degradation (see below). We next found that both ulp2-F839D and ulp2-2A caused a silencing defect at NTS1, while the ulp2-F827D mutant did not, in overall agreement with our data on Tof2 abundance (Fig. 5C). The observation of strong silencing defects in ulp2-F839D and ulp2-2A, which showed only modest reductions in Tof2 abundance, were initially puzzling. We found previously that protein polysumoylation (i.e., SUMO chain formation on substrates) is partially compromised in the HF-SUMO strain (de Albuquerque et al. 2016), suggesting that if polysumoylation is necessary for Tof2 degradation, the HF-SUMO strain background might suppress this effect. We therefore examined Tof2 abundance in cells with untagged wild-type SMT3 and found that, in this background, both ulp2-2A and ulp2-F839D cause a much more dramatic reduction in Tof2 abundance (Fig. 5D). These data suggest that polysumoylation of Tof2 is likely critical for its instability in ulp2 mutants. Together, these results confirm that Ulp2 binding to Csm1 is necessary to desumoylate and stabilize Tof2, thereby maintaining robust rDNA silencing.

Figure 5.

Ulp2–Csm1 binding is required for rDNA silencing and maintenance of Tof2 abundance. (A,B) Western blot of Tof2 after purifying for sumoylated protein in wild-type and ulp2 mutants defective in Csm1 binding: ulp2-781Δ, ulp2-F827D, ulp2-F839D, and ulp2-2A(F827,839A). (C) The effect of ulp2 mutants defective in Csm1 binding as in A on rDNA silencing at the NTS1 locus. (D) Western blot of Tof2 abundance in cells with wild-type SMT3 and various ulp2 mutants.

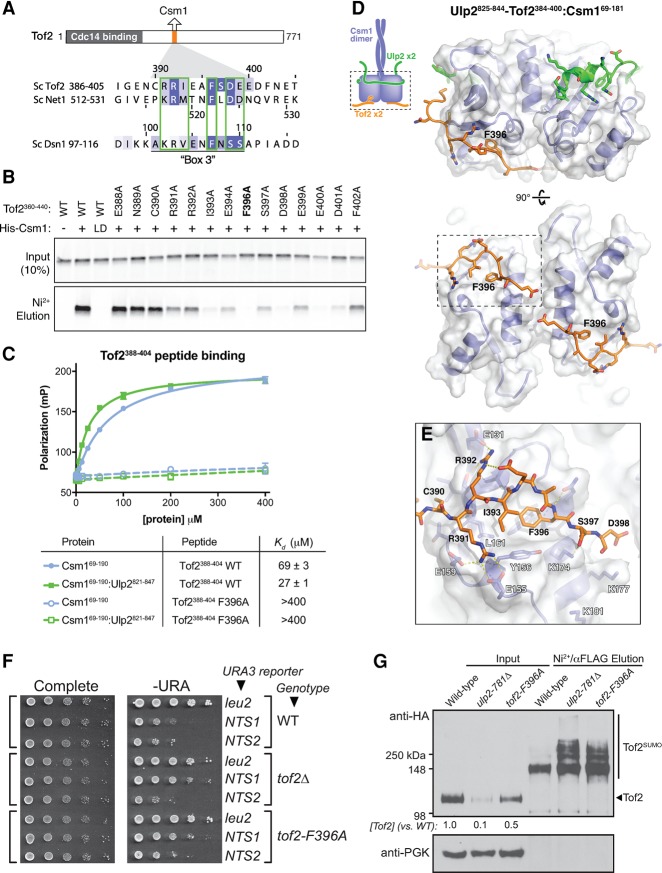

A conserved motif in Tof2 mediates Csm1 binding and is required for rDNA silencing

We showed previously that Csm1 binds Tof2 through a conserved hydrophobic surface on its C-terminal globular domain but did not identify the region of Tof2 responsible for this interaction (Corbett et al. 2010). Using pull-down assays with in vitro translated Tof2 fragments, we identified a short motif between residues 390 and 400, conserved in fungal Tof2 and Net1 proteins, that is sufficient for Csm1 binding and whose binding is disrupted by the Csm1 conserved patch mutant L161D (Fig. 6A,B; Supplemental Fig. 4). This motif contains two conserved basic residues (R391/R392 in Tof2) followed by two hydrophobic residues (I393 and F396) and then two to four acidic residues (D398–D401). While mutation of either R391 or R392 to alanine had little effect on Csm1 binding, alanine mutations of either conserved hydrophobic residue (I393A and F396A) or most of the acidic residues (D398A, E400A, and D401A) strongly affected binding in a pull-down assay (Fig. 6B). We found that the equivalent region of Net1 (residues ∼516–526) also binds Csm1, albeit considerably more weakly than Tof2, and that this interaction is disrupted by mutation of Net1 residues R518, M519, F522, or D524 (Supplemental Fig. 5A). We next used a fluorescence polarization assay to more quantitatively test binding of Csm1 to a synthetic Tof2388–404 peptide and a second peptide containing the F396A mutation (this mutation had the most severe effect on Csm1 binding in our pull-down assays) (see the “high-exposure” panel in Supplemental Fig. 5A). We found that both Csm169–190 and the Ulp2821–847:Csm169–190 complex bound to the wild-type Tof2388–404 peptide, but neither detectably bound the peptide containing the F396A mutation (Fig. 6C). These data indicate that Tof2 and Ulp2 can simultaneously bind to Csm1.

Figure 6.

A conserved motif in Tof2 and Net1 binds the conserved hydrophobic surface of Csm1. (A) Schematic of the Cdc14-binding (residues 1–270) (Waples et al. 2009) and Csm1-binding (residues 390–400) (see Supplemental Fig. S5) regions of Tof2 and the sequence of the Csm1-binding region from Tof2 aligned with equivalent regions in Net1 and Dsn1. (B) Pull-down assay showing the effects of Tof2 point mutations on Tof2–Csm1 binding. Binding is disrupted by the Csm1 L161D mutation (LD), implicating the Csm1 conserved hydrophobic surface in Tof2 interaction. We observed similar results with the equivalent region of Net1, including the disruption of binding by the Csm1 L161D mutation (Supplemental Fig. 5A). (C) Fluorescence polarization assay measuring binding of Csm169–190 (blue) or Ulp2821–847:Csm169–190 (green) to a fluorescently labeled Tof2388–404 peptide (Tof2 wild type; solid lines) or the same peptide with an F396A mutation (Tof2 F396A; dashed lines). See Supplemental Figure 5B for binding of Ulp2825–844–Tof2384–400:Csm169–190 to these peptides. (D) Side and bottom views of the Csm169–181:Ulp2825–844–Tof2384–400 structure, with Csm1 in blue, Ulp2 in green, and Tof2 in orange. (E) Close-up view of Tof2's interaction with the Csm1 conserved hydrophobic surface. (F) The effect of Csm1 and Tof2 point mutations on rDNA silencing. (G) The effect of Csm1 and Tof2 point mutations on Tof2 sumoylation and abundance following purification of total sumoylated proteins for Western blot analysis as indicated.

We attempted to cocrystallize the conserved Tof2 motif with Csm1 to understand the structural basis of their interaction. After failing to obtain crystals of the complex with a Tof2 peptide (data not shown), we designed a series of constructs fusing the Csm1-binding regions of Ulp2 and Tof2 with different length linkers. The best-behaved fusion construct included Ulp2 residues 825–844 fused directly to Tof2 residues 384–400 (Ulp2825–844–Tof2384–400), which formed a stable 2:2 complex with Csm1 when coexpressed in E. coli. Importantly, the purified Ulp2825–844–Tof2384–400:Csm169–190 complex did not bind the Tof2388–404 peptide (Supplemental Fig. 5B), supporting the idea that the Tof2 region of this fusion construct occupies its native binding site on Csm1.

We obtained crystals of the Ulp2825–844–Tof2384–400:Csm169–181 complex and determined its structure to a resolution of 1.3 Å (Supplemental Table 4). In this structure, Ulp2825–844 binds Csm1 as described above (Fig. 6D), except that Y826 and F827 interact with a crystallographic symmetry-related Csm1 dimer instead of the same dimer as in the Ulp2821–847:Csm169–181 structure (Supplemental Fig. 6C,D). The residues near the Ulp2–Tof2 fusion junction are disordered, but Tof2 residues 389–398 are clearly visible, bound to the Csm1 conserved hydrophobic surface (Fig. 6D,E). Tof2 C390 docks into a small hydrophobic patch on Csm1, while Tof2 R391 and R392 form hydrogen-bonding interactions with several conserved acidic residues in Csm1. The Tof2 hydrophobic residues I393 and F396 dock into the previously identified bowl-shaped hydrophobic surface on Csm1, with F396 in particular deeply nestled among several hydrophobic Csm1 residues. Finally, Tof2 residues S397 and D398 appear to interact electrostatically with several lysine residues in Csm1, including K174 and K177. While not visible in our structure, the negatively charged C terminus of the Tof2 motif (residues 398–401; DEED) may also interact electrostatically with positively charged residues in Csm1's disordered C-terminal region (residues 181–190; KKREKKDETE). Overall, the structure reveals high specificity in the Tof2–Csm1 interaction, incorporating both polar and hydrophobic interactions. Comparison of the Tof2 motif with Dsn1, which we previously found binds the same Csm1 surface, reveals a similar sequence in one segment of its Csm1-binding region, termed “box 3” (Fig. 6A; Sarkar et al. 2013). Dsn1 box 3 contains two positively charged residues (K102 and R103) followed by two hydrophobic residues: V104 and the highly conserved F107. In place of Tof2's acidic residues at the C terminus of the motif, Dsn1 contains two conserved serine residues (S109/S110), hinting that phosphorylation of these residues could modulate the Dsn1–Csm1 interaction by introducing negative charges that could interact with Csm1's positively charged C terminus. Overall, our structural data on Csm1's interactions with both Ulp2 and Tof2 and their parallels with Mam1 and Dsn1, respectively, reveals that Csm1 uses a common set of protein–protein interfaces to nucleate assembly of functionally divergent protein complexes in the nucleolus and at meiotic kinetochores.

Given its effect on Csm1 binding in vitro, we next examined the effects of the tof2-F396A mutation on rDNA silencing and Tof2 abundance/polysumoylation. The tof2Δ mutant was shown previously to disrupt silencing at NTS1 (Huang et al. 2006), and we observed a similar loss of silencing in the tof2-F396A mutant (Fig. 6F). This effect is equivalent to that of the csm1-L161D mutant, which disrupts binding to both Tof2 and Dsn1 (Supplemental Fig. 1D; Corbett et al. 2010). The tof2-F396A mutant also causes elevated Tof2 sumoylation and a significant loss of abundance at least equivalent to the effect of ulp2-F839D in this strain (Fig. 6G). We also found that, as expected, the tof2-F396A and ulp2-F839D mutations are epistatic, with the double mutant showing silencing at NTS1 similar to either single mutant (Supplemental Fig. 7A). Together, these findings confirm that binding of Ulp2 and Tof2 to distinct surfaces on Csm1 facilitates Ulp2-mediated Tof2 desumoylation and stabilization.

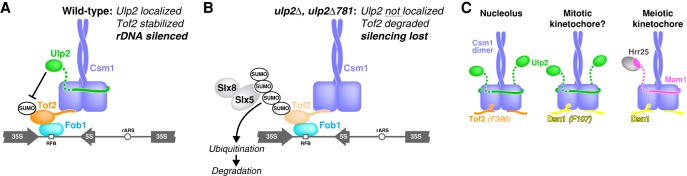

Slx5 and its SIMs are required for the reduction of Tof2 abundance

Our finding that increased Tof2 sumoylation is accompanied by a marked loss in protein abundance suggests that sumoylation may induce Tof2 degradation through the action of a STUbL. To address this, we examined whether Slx5 (Fig. 7A) plays a role in regulating Tof2 abundance. We first examined Tof2 abundance in ulp2, slx5Δ, and ulp2 slx5Δ double-mutant cells and found that while the slx5Δ mutant alone has little effect on Tof2 abundance, it strongly suppresses the loss of Tof2 abundance caused by ulp2Δ and ulp2-781Δ (Fig. 7B). We also tested more specifically the role of the Slx5 SIMs (Xie et al. 2010), which recognize SUMO-conjugated substrates (Song et al. 2004). We found that disruption of Slx5's four SIMs (slx5-sim) strongly suppresses the loss of Tof2 abundance seen in ulp2-781Δ, indicating that specific recognition of sumoylated Tof2 by Slx5 is required for its loss of abundance (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

The roles of Slx5 in rDNA silencing and the control of Tof2 abundance. (A) Schematic of Slx5 showing SIMs 1–5 and the C-terminal RING domain. In the slx5-sim mutant, SIMs 1–4 are disrupted (SIM #1: VILI24–27 → VAAA; SIM #2: ITII93–96 → ATAA; SIM #3: VDLD116–119 → AAAD; SIM #4: LTIV155–158 → ATAA) (Xie et al. 2010). (B) slx5Δ and slx5-sim rescue the loss of Tof2 abundance caused by ulp2Δ and ulp2-781Δ mutations in strains with HF-SUMO. (C) slx5Δ rescues the loss of Tof2 abundance in ulp2-F839D and tof2-F396A mutants in strains with untagged wild-type SMT3. (D) slx5Δ rescues the loss of rDNA silencing at NTS1 in ulp2-F839D and tof2-F396A mutants.

We next examined whether slx5Δ could suppress the effects on Tof2 abundance and rDNA silencing caused by ulp2-F839D and tof2-F396A mutants. It was reported previously that the slx5Δ mutant alone affects rDNA silencing at NTS1 (Darst et al. 2008), but we found no such defect in our slx5Δ single mutant (this difference may be due to a lack of the 2-µm plasmid in our strains) (Fig. 7D; see the Materials and Methods). When we combined slx5Δ with either ulp2-F839D or tof2-F396A, we observed a strong suppression of Tof2 abundance loss in both strains (Fig. 7C) as well as restoration of NTS1 silencing to the ulp2-F839D mutant (Fig. 7D). Interestingly, slx5Δ did not fully restore NTS1 silencing in the tof2-F396A mutant (Fig. 7D). Since localization of Csm1 and its associated proteins is still defective in the tof2-F396A slx5Δ double mutant, Tof2 stabilization alone appears insufficient to rescue rDNA silencing. Together, these findings demonstrate that the Slx5:Slx8 STUbL mediates the degradation of polysumoylated Tof2 and that Ulp2 desumoylates Tof2 to stabilize it against this degradation.

Discussion

Protein sumoylation plays important roles in a wide range of cellular pathways, yet the molecular basis for substrate specificity in sumoylation and desumoylation enzymes is not well understood. We showed previously that of the two known SUMO isopeptidases in S. cerevisiae, Ulp1 is responsible for most desumoylation, while Ulp2 shows strong specificity for proteins associated with the rDNA, centromeres, and origins of DNA replication (de Albuquerque et al. 2016). Here, we identify a region in Ulp2's previously uncharacterized C terminus that interacts with Csm1, thereby mediating its specificity for rDNA-associated—and likely also centromere-associated—proteins. We show that Ulp2 plays an important role in rDNA silencing by desumoylating the RENT-associated Tof2 protein, thereby stabilizing it against ubiquitination by the STUbL Slx5:Slx8 and subsequent degradation.

The Csm1:Lrs4 complex leads a double life. As the “cohibin” complex, these proteins participate in rDNA copy number maintenance and silencing in association with the RENT complex, but, during meiotic prophase, they take on a second role as part of the monopolin complex to regulate kinetochore–microtubule attachments (Huang and Moazed 2003; Huang et al. 2006; Mekhail et al. 2008; Brito et al. 2010; Corbett et al. 2010). Our structural and biochemical data now show how Csm1 recruits Ulp2 to the rDNA and also reveal that Csm1 uses a common set of protein–protein interfaces to nucleate functionally distinct protein complexes in these two different contexts (Fig. 8C). Ulp2 and the meiosis-specific monopolin subunit Mam1 bind Csm1 in a strikingly similar manner, and Tof2 binding to the conserved hydrophobic surface on Csm1 is likely similar to that of the kinetochore protein Dsn1. While Csm1:Lrs4 is now known to bind Ulp2/Tof2 at the rDNA and Mam1/Dsn1 at meiotic kinetochores, there may also be some overlap between these roles. Csm1:Lrs4 localizes to kinetochores in mitotic anaphase, where it contributes to the fidelity of chromosome segregation in an unknown manner (Brito et al. 2010). Our MS data show an increase in sumoylation of the inner kinetochore proteins Mcm21, Okp1, and Mcm22 in mutants where Ulp2–Csm1 binding is disrupted (Fig. 3B), suggesting that Csm1 may recruit Ulp2 to kinetochores in mitotic cells (Fig. 8C). Interestingly, depletion of SENP6, the human ortholog of Ulp2, was shown to cause degradation of the inner kinetochore protein CENP-I (Mukhopadhyay et al. 2010). CENP-I is the human ortholog of yeast Ctf3 and a member of the so-called constitutive centromere-associated network (CCAN), which in yeast also includes the Ulp2 substrates Mcm21, Okp1, and Mcm22 (Westermann et al. 2007). How Ulp2 localization and desumoylation of inner kinetochore CCAN proteins might contribute to chromosome segregation fidelity in mitosis and potentially also in meiosis will be an intriguing avenue for future research.

Figure 8.

Control of rDNA silencing complexes by sumoylation/desumoylation. (A) Model for Ulp2's contribution to rDNA silencing. In the nucleolus, Ulp2 (green) desumoylates Tof2 to inhibit its Slx5-mediated degradation, thereby maintaining RENT complex stability and rDNA silencing. (B) In the absence of Ulp2 localization, Tof2 is extensively sumoylated and targeted for degradation by Slx5:Slx8, compromising RENT complex stability and rDNA silencing. (C) Csm1 nucleates distinct complexes in different contexts. (Left) In the nucleolus, Csm1 binds Tof2 via the conserved hydrophobic surface patch and Ulp2 on the “sides” of the dimer. (Right) At the meiotic kinetochore, the same Csm1 surfaces mediate binding of Dsn1 and Mam1, respectively. (Middle) Our MS data (Fig. 2B) suggest that when Csm1:Lrs4 localizes to kinetochores in mitotic anaphase, it may recruit Ulp2 to desumoylate kinetochore proteins.

A well-known function of Ulp2 is to prevent accumulation of polysumoylation of its substrates (Bylebyl et al. 2003). Considering Slx5's ability to bind poly-SUMO chains via its multiple SIMs (Xie et al. 2007, 2010), one might expect that Ulp2 substrates could be preferentially targeted by Slx5, especially in cells lacking Ulp2, where these proteins become highly polysumoylated. However, our prior analysis of Net1 and MCM subunits in the ulp2Δ mutant did not reveal any evidence that Ulp2 controls these proteins’ overall abundance (de Albuquerque et al. 2016). While these findings initially cast doubt on the functional link between polysumoylation and STUbL-mediated degradation, we now show that Tof2 undergoes SUMO- and Slx5- dependent degradation that is suppressed by Ulp2. These data provide a mechanistic explanation for the recent finding that deletion of ULP2 causes loss of Tof2 from rDNA and that localization is rescued by further deletion of SLX5 (Gillies et al. 2016). We speculate that a similar antagonism between desumoylation and STUbL-mediated degradation might also regulate the abundance of other Ulp2 substrates, including those at the inner kinetochore and at DNA replication origins.

A remaining question is the apparent specificity of Slx5:Slx8 for Tof2 versus Net1. Prior work has suggested that Slx5:Slx8, preferentially ubiquitinates proteins conjugated with SUMO chains in vitro (Mullen and Brill 2008). Our finding that the HF-SUMO strain, in which SUMO chain formation is partially compromised (de Albuquerque et al. 2016), shows weaker Tof2 abundance losses in mutant strains compared with a wild-type background supports this idea. We further found that the smt3-allR mutation, which eliminates any branched SUMO chain formation, although linear SUMO chains could still form (Bylebyl et al. 2003), rescues rDNA silencing at NTS1 in the ulp2-F839D mutant (Supplemental Fig. 7B), suggesting a role for poly-SUMO chains in this process. In addition to poly-SUMO chain formation, a second factor governing Slx5 recognition may be the overall number of SUMO-modified lysine residues in the substrate protein. We identified 10 modified lysine residues in Tof2 versus only two for Net1 (Supplemental Tables 5, 6; Wohlschlegel et al. 2006; Albuquerque et al. 2015), raising the possibility that multiple poly-SUMO chains on Tof2 could further contribute to its specific recognition by Slx5. While these findings are in general agreement with the known function of Slx5 in targeting sumoylated substrates, further investigation into the in vivo determinants for substrate recognition by Slx5:Slx8, particularly the relative contributions of SUMO chain formation and the number and precise locations of sumoylated lysine residues on its substrate, should provide important insights into how this STUbL enzyme functions.

Taken together, the findings presented here reveal a key role for Csm1 in dictating the substrate specificity of Ulp2 through direct binding and recruitment to its substrates. Ulp2 in turn plays an important role in rDNA silencing by desumoylating Tof2 and preventing its Slx5-mediated degradation, demonstrating how opposing actions of a SUMO isopeptidase and a STUbL can maintain protein homeostasis. The specific recruitment of Ulp2 to other chromosomal loci, including kinetochores (possibly through Csm1) and DNA replication origins (through a currently unknown mechanism), likely plays a similar role in regulating the stability of key protein complexes at these loci.

Materials and methods

Construction of plasmids and yeast strains

Yeast strain construction was performed using standard methods. Yeast strains used here had their 2-µm circles removed where noted and were generated similar to a previous study (Chen et al. 2005).

Protein expression and purification

The Ulp2 C-terminal domain Ulp2781–873 was cloned into a pET3a-derived vector containing an N-terminal His6-GST tag and expressed in E. coli Rosetta2 DE3 pLysS cells (EMD Millipore). Ulp2 point mutations were cloned by PCR mutagenesis. The recombinant Ulp2 C-terminal domain (full-length and point mutants) was purified using glutathione affinity sepharose resin (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) followed by cation exchange (HiTrap SP HP, GE Healthcare Life Sciences) chromatography before pooling fractions and concentrating. We expressed Csm1 as described previously (Corbett et al. 2010). Briefly, we cloned full-length S. cerevisiae Csm1 (or the 69–190 or 69–181 truncations) into a pET3a-derived vector containing an N-terminal His6 tag and expressed the protein in E. coli Rosetta2 DE3 pLysS cells (EMD Millipore) for 16 h at 20°C in 2× YT medium by induction with 0.25 mM IPTG. We purified Csm1 using Ni2+ affinity (Qiagen Ni-NTA Superflow), anion exchange (HiTrap Q HP, GE Life Sciences), and size exclusion (Superdex 200, GE Life Sciences) chromatography; concentrated the protein; and snap-froze aliquots for biochemical assays. For Ulp2:Csm1 complexes (and Ulp2–Tof2 fusion:Csm1 complexes), we generated a coexpression vector with Ulp2 fragments fused to a TEV protease-cleavable N-terminal His6-SUMO-tagged and untagged Csm169–181 (for crystallography) or Csm169–190 (for Tof2-binding assays). The complexes were purified with Ni2+ affinity chromatography followed by tag cleavage with TEV protease and removal of tags and uncleaved protein with Ni2+ resin and then passed over a Superdex 200 size exclusion column in a final buffer of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 300 mM NaCl. The protein was concentrated and stored at 4°C for crystal trays.

ChIP-qPCR

For analysis of Ulp2 localization to rDNA, ChIP was carried out as described previously (Nelson et al. 2006). Yeast cultures (50 mL for each immunoprecipitation) were grown to an OD600 of 0.8 and cross-linked for 1 h in 1% formaldehyde. qPCR was performed using SYBR Green 2× master mix on a Roche LightCycler 480. The input was diluted 1:100, and immunoprecipitated samples were diluted 1:5 in water. The fold enrichment was calculated as an average of triplicate experiments. Genomic DNA was prepared from HZY4162 cells to make serial dilutions in order to calculate relative amounts of DNA per primer pair using a standard curve. Fold enrichment values were calculated as described previously [rDNA(immunoprecipitate)/CUP1(immunoprecipitate)]/[rDNA(input)/CUP1(input)] (Huang and Moazed 2003) and normalized to the untagged reactions. Primer pairs used were as described previously (Huang et al. 2006): #7 (ATCCGGAGATGGGGTCTTAT/CTGACCAAGGCCCTCACTAC); #9 (CTAGCGAAACCACAGCCAAG/AATGTCTTCAACCCGGATCA), #11 (TGGCAGTCAAGCGTTCATAG/CAGCCGCAAAAACCAATTAT), #13 (TTTGCGTGGGGATAAATCAT/CATGTTTTTACCCGGATCAT), #15 (AGGGCTTTCACAAAGCTTCC/TCCCCACTGTTCACTGTTCA), #17 (GGAAAGCGGGAAGGAATAAG/CGATTCAGAAAAATTCGCACT), #19 (GAGGTGTTATGGGTGGAGGA/GCCACCATCCATTTGTCTTT), #21 (AGAGGAAAAGGTGCGGAAAT/TTTCTGCCTTTTTCGGTGAC), #23 (GGGAGGTACTTCATGCGAAA/AAGATGCCCACGATGAGACT), and #25 (GGCAGCAGAGAGACCTGAAA/GAGCCATTCGCAGTTTCACT).

Protein interaction assays

For quantitative MS analysis of Ulp2-associated proteins in wild-type and ulp2-781Δ cells, a C-terminal TAF (Chen et al. 2007) tag was integrated in the endogenous ULP2 locus. ULP2-TAF cells were grown in SILAC heavy-labeled Lys/Arg medium, and ulp2-781Δ cells were grown in SILAC light-labeled Lys/Arg medium. Cells were harvested, washed with TBSN (50 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.2% NP-40), and resuspended in 0.25 vol of cell pellet with TBSN buffer (protease inhibitors: 2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 200 µM benzamidine, 0.5 µg/mL leupeptin, 1 µg/mL pepstatin A) before being frozen drop-wise in liquid nitrogen. Cells (3 g per sample) were ground using a SPEX SamplePrep 6875D freezer/mill and then thawed in 0.25 vol of 4× glycerol mix buffer (40% glycerol, 100 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 0.4% NP-40) and 4× concentration of protease inhibitors. Lysate was cleared by ultrahigh-speed centrifugation, and protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay. Both Ulp2-TAF and Ulp2-781Δ-TAF were purified separately using a two-step purification. Briefly, equal amounts (∼60 mg) of cell lysate were incubated with anti-Flag M2 resin for 2 h at 4°C. After washing with TBSN buffer, Ulp2 and associated proteins were eluted with 0.2 mg/mL 3x-Flag peptide in TBSN buffer. Eluted samples were then bound to IgG sepharose resins for 2 h at 4°C, washed with TBSN buffer, and finally eluted by a buffer containing 8 M urea and 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). Eluents were combined and processed for quantitative MS analysis. For coimmunoprecipitation experiments, similar methods were used to prepare cell lysate, except that IgG sepharose resins were used to purify Ulp2-TAF, which was eluted by 1% SDS buffer, and the associated Csm1 was detected using anti-HA antibody.

To analyze the interaction between Ulp2 and Csm1 by pull-down, either GST-Ulp2781–873 or GST alone was incubated with 10 µg of bait protein (His6-Csm1 or His6-Csm69–181) in 40 µL of binding buffer (20 mM HEPES at pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% NP-40) for 90 min at 4°C. Ten percent of the purification was removed to be analyzed as input, and the remaining fraction was bound to glutathione sepharose beads for 2 h at 4°C. The beads were washed three times with 0.5 mL of binding buffer, eluted with 25 µL of elution buffer (25 mM glutathione in 2× LDS sample buffer), and boiled. The eluted proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie staining.

For in vitro translation of Tof2 and Net1 fragments in rabbit reticulocyte lysate, expression constructs were cloned into a pET3a-derived vector containing a Kozak sequence (CCGCCACC) and an N-terminal maltose-binding protein (MBP tag), and point mutants were generated by PCR mutagenesis. Purified plasmid DNA (Qiagen Miniprep kit) was added to a coupled transcription/translation kit (TNT T7, Promega) in the presence of 35S-methionine. For pull-down assays, 10 µL of transcribed protein mix was incubated with 10 µg of bait protein (His6-Csm1, His6-Csm1-L161D, or His6-SUMO-Ulp2821:847:Csm169–190) in 50 µL of buffer (20 mM HEPES at pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% NP-40) for 90 min at 4°C, 15 µL of Ni-NTA beads was added, and the mixture was incubated a further 45 min. Beads were washed three times with 0.5 mL of buffer, eluted with 25 µL of elution buffer (2× SDS-PAGE loading dye plus 250 mM imidazole), and boiled. Samples were run on SDS-PAGE, dried, and scanned with a phosphorimager.

For fluorescence polarization assays, N-terminal FITC-labeled peptides (β-alanine linkage) were synthesized (Tufts University Core Facility) and resuspended in binding buffer (20 mM HEPES at pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% NP-40). Fifty-microliter reactions containing 10 nM peptide plus 200 nM to 400 µM Csm169–190 or Ulp2821–847:Csm169–190 (concentration expressed in terms of Csm1 monomer concentration) were incubated for 30 min at room temperature, and fluorescence polarization was read in 384-well plates using a TECAN Infinite M1000 Pro fluorescence plate reader. All binding curves were done in triplicate. Binding data were analyzed with Graphpad Prism version 7 using a single-site-binding model. The peptides used were Tof2 wild type (residues 388–404 with C390A and F402A mutations to increase peptide solubility) fluorescein-ENARRIEAFSDEEDANE and Tof2 F396A (as Tof2 wild type with F396A mutation) fluorescein-ENARRIEAASDEEDANE.

Isothermal titration calorimetry was performed at the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute Protein Analysis Core Facility. Assays were performed in buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 270 mM NaCl, and 1 mM DTT using an ITC200 calorimeter from Microcal. Nineteen 2.0-µL aliquots of solution containing 700 µM His6-GST-Ulp2781–873 were injected into the cell containing 200 µL of 102 µM (monomer concentration) His6-Csm169–190 at 23°C. For Ulp2 F839D, 1.68 mM His6-GST-Ulp2781–873 F839D was added to 266 µM Csm1. Data were analyzed using Origin software provided by Microcal.

Analysis of Tof2 sumoylation and sumoylation sites on Net1 and Tof2

Total sumoylated proteins were purified from an HF-SMT3 strain (His6-3xFlag-SMT3) containing HA-tagged TOF2 using Ni-NTA (Qiagen) followed by anti-Flag affinity resin as described previously (de Albuquerque et al. 2016). Tof2 and the slower-migrating Tof2–SUMO conjugates were detected by anti-HA Western blot. To detect the abundance of Tof2 in whole-cell lysate, equal amounts of cell lysate were used, and anti-PGK antibody was used to confirm equal loading. To identify sumoylation sites, we used a similar method described previously (Albuquerque et al. 2015) to identify lysines modified with a diglycine remnant (K-ε-GG) in a strain with HF-smt3-I96R ulp2Δ. After the initial Ni-NTA/anti-Flag purification, sumoylated proteins were eluted using 6 M urea, 100 mM sodium carbonate, and 0.2% NP-40 and neutralized by HCl. Eluate was rebound by fresh Ni-NTA resins and washed, and sumoylated proteins were digested by trypsin in PBS buffer containing 0.2% NP-40 for MS analysis.

Gene silencing assay

Silencing assays were performed similarly to as described (Huang and Moazed 2003; Huang et al. 2006). Yeast strains (Supplemental Table 7) were grown overnight in YPD and then normalized to an equal density. Tenfold serial dilutions were plated on CSM complete and CSM−URA plates for rDNA silencing, CSM−TRP for HMR locus silencing, and CSM 5-FOA for telomere silencing strains. Plates were incubated for at least 3 d at 30°C before imaging.

Quantitative MS analysis of intracellular sumoylation

The quantitative MS analysis used to measure changes in sumoylated protein abundance between two strains was described previously (Albuquerque et al. 2013). Each mutant strain was grown in synthetic medium containing either light or heavy stable isotope-labeled lysine and arginine. Cell pellets of the two yeast strains to be compared were combined and used to purify sumoylated proteins under denaturing conditions for quantitative MS analysis. MS data were searched using Sequest on a Sorcerer 2 (Sage-N) system and quantified using Xpress (Trans-Proteomic Pipeline version 4.3). Complete lists of sumoylated proteins and their abundance changes are in Supplemental Tables 2 (ulp2-781Δ) and 3 (csm1Δ). Each sumoylated protein was quantified based on the median of the abundance ratios of at least three unique peptides per protein. A minimal ion intensity of 1.0 × 10−3 was used to calculate abundance ratios when corresponding peptides were below the detection limit.

Crystallography

We obtained crystals of Ulp2821–847:Csm169–181 by mixing 15 mg/mL protein 1:1 in a crystallization buffer containing 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) and 20% PEG 3350 in hanging drop format. We added 25% glycerol for cryoprotection, flash-froze crystals in liquid nitrogen, and collected diffraction data on Beamline 14-1 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource. We integrated and scaled all data sets with HKL2000 (Otwinowski and Minor 1997) and converted to structure factors with Truncate (Winn et al. 2011). We determined the structure by molecular replacement in Phaser (McCoy et al. 2007) using a previous structure of Csm1 (Protein Data Bank ID 3N4S) (Corbett et al. 2010). We manually built Ulp2 residues 821–845 into difference density maps in COOT (Emsley et al. 2010), guided by the structure of Mam1221–290:Csm1 (Protein Data Bank ID 4EMC). We refined the model in phenix.refine (Afonine et al. 2012) using positional, individual B-factor, and TLS refinement (statistics in Supplemental Table 4).

We obtained crystals of the Ulp2825–844–Tof2384–400:Csm169–181 complex by mixing 15 mg/mL protein 1:1 in a crystallization buffer containing 0.2 M ammonium acetate, 0.1 M HEPES (pH 7.5), and 25% PEG 3350. We added 25% glycerol for cryoprotection, flash-froze crystals in liquid nitrogen, and collected diffraction data on Beamline 24ID-E at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory. Data were processed using the RAPD pipeline (https://github.com/RAPD/RAPD; Frank Murphy), which uses XDS (Kabsch 2010) for data indexing and reduction, Aimless (Evans and Murshudov 2013) for scaling, and Truncate (Winn et al. 2011) for conversion to structure factors. We determined the structure by molecular replacement, rebuilt it, and refined it as above (statistics in Supplemental Table 4).

By comparison of the final Ulp2821–847:Csm169–181 complex structure with our previous 3.05 Å-resolution structure of Mam1221–290:Csm1 (Protein Data Bank ID 4EMC) (Corbett and Harrison 2012), we identified a register error in the N-terminal region of the Mam1 model due to a missing residue around residue 239. After rebuilding and rerefinement, the Mam1221–290:Csm1 structure shows a significantly lower Rfree value than the original structure (24.1% vs. 26.0%), and a structure-based sequence alignment of the Csm1-binding regions of Mam1 and Ulp2 shows a strong similarity between pairs of Csm1-binding residues (Fig. 4A). The updated structure of Mam1221–290:Csm1 has been deposited at the Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics Protein Data Bank under accession number 5KTB (superseding 4EMC).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staffs of Beamline 14-1 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (SSRL) and Beamline 24ID-E at the Advanced Photon Source for assistance with diffraction data collection, Andrey Bobkov for assistance with isothermal titration calorimetry, and members of the Zhou and Corbett laboratories for helpful discussions and comments. We thank Mark Hochstrasser for slx5-sim plasmid, and Danesh Moazed and Lorraine Pillus for yeast strains. Use of the SSRL, Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC) National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under contract number DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and the National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393). This work is based on research conducted at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team beamlines, which are funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences from the National Institutes of Health (P41 GM103403). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a DOE Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under contract number DE-AC02-06CH11357. This work was supported by the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research (to H.Z. and K.D.C.), National Cancer Institute training grant T32 CA009523 (to J.L.), and National Institutes of Health (R01-GM116897 to H.Z., and R01-GM104141 to K.D.C.). H.Z., K.D.C., J.L., and N.S. designed the project and formulated experiments. J.L. performed yeast genetics experiments with the help of C.R.C., J.L. and C.P.A. performed MS analysis, N.S. and J.L. performed biochemical assays with purified proteins with the assistance of C.R.C., and N.S. determined crystal structures. H.Z. and K.D.C. wrote the paper with input from all other authors.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available for this article.

Article published online ahead of print. Article and publication date are is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.296145.117.

References

- Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Mustyakimov M, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, Zwart PH, Adams PD. 2012. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 68: 352–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque CP, Wang G, Lee NS, Kolodner RD, Putnam CD, Zhou H. 2013. Distinct SUMO ligases cooperate with Esc2 and Slx5 to suppress duplication-mediated genome rearrangements. PLoS Genet 9: e1003670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque CP, Yeung E, Ma S, Fu T, Corbett KD, Zhou H. 2015. A chemical and enzymatic approach to study site-specific sumoylation. PLoS One 10: e0143810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito IL, Monje-Casas F, Amon A. 2010. The Lrs4–Csm1 monopolin complex associates with kinetochores during anaphase and is required for accurate chromosome segregation. Cell Cycle 9: 3611–3618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylebyl GR, Belichenko I, Johnson ES. 2003. The SUMO isopeptidase Ulp2 prevents accumulation of SUMO chains in yeast. J Biol Chem 278: 44113–44120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XL, Reindle A, Johnson ES. 2005. Misregulation of 2 microm circle copy number in a SUMO pathway mutant. Mol Cell Biol 25: 4311–4320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SH, Smolka MB, Zhou H. 2007. Mechanism of Dun1 activation by Rad53 phosphorylation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 282: 986–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett KD, Harrison SC. 2012. Molecular architecture of the yeast monopolin complex. Cell Rep 1: 583–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett KD, Yip CK, Ee LS, Walz T, Amon A, Harrison SC. 2010. The monopolin complex crosslinks kinetochore components to regulate chromosome-microtubule attachments. Cell 142: 556–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremona CA, Sarangi P, Yang Y, Hang LE, Rahman S, Zhao X. 2012. Extensive DNA damage-induced sumoylation contributes to replication and repair and acts in addition to the mec1 checkpoint. Mol Cell 45: 422–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darst RP, Garcia SN, Koch MR, Pillus L. 2008. Slx5 promotes transcriptional silencing and is required for robust growth in the absence of Sir2. Mol Cell Biol 28: 1361–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Albuquerque CP, Liang J, Gaut NJ, Zhou H. 2016. Molecular circuitry of the SUMO (small ubiquitin-like modifier) pathway in controlling sumoylation homeostasis and suppressing genome rearrangements. J Biol Chem 291: 8825–8835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elion EA, Warner JR. 1986. An RNA polymerase I enhancer in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol 6: 2089–2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. 2010. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66: 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans PR, Murshudov GN. 2013. How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 69: 1204–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gareau JR, Lima CD. 2010. The SUMO pathway: emerging mechanisms that shape specificity, conjugation and recognition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 11: 861–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies J, Hickey CM, Su D, Wu Z, Peng J, Hochstrasser M. 2016. SUMO pathway modulation of regulatory protein binding at the ribosomal DNA locus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 202: 1377–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Moazed D. 2003. Association of the RENT complex with nontranscribed and coding regions of rDNA and a regional requirement for the replication fork block protein Fob1 in rDNA silencing. Genes Dev 17: 2162–2176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Brito IL, Villen J, Gygi SP, Amon A, Moazed D. 2006. Inhibition of homologous recombination by a cohesin-associated clamp complex recruited to the rDNA recombination enhancer. Genes Dev 20: 2887–2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ES. 2004. Protein modification by SUMO. Annu Rev Biochem 73: 355–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ES, Gupta AA. 2001. An E3-like factor that promotes SUMO conjugation to the yeast septins. Cell 106: 735–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. 2010. Xds. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66: 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SJ, Hochstrasser M. 1999. A new protease required for cell-cycle progression in yeast. Nature 398: 246–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SJ, Hochstrasser M. 2000. The yeast ULP2 (SMT4) gene encodes a novel protease specific for the ubiquitin-like Smt3 protein. Mol Cell Biol 20: 2367–2377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. 2007. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Crystallogr 40: 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekhail K, Seebacher J, Gygi SP, Moazed D. 2008. Role for perinuclear chromosome tethering in maintenance of genome stability. Nature 456: 667–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay D, Arnaoutov A, Dasso M. 2010. The SUMO protease SENP6 is essential for inner kinetochore assembly. J Cell Biol 188: 681–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen JR, Brill SJ. 2008. Activation of the Slx5–Slx8 ubiquitin ligase by poly-small ubiquitin-like modifier conjugates. J Biol Chem 283: 19912–19921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JD, Denisenko O, Bomsztyk K. 2006. Protocol for the fast chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) method. Nat Protoc 1: 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie M, Boddy MN. 2015. Pli1(PIAS1) SUMO ligase protected by the nuclear pore-associated SUMO protease Ulp1SENP1/2. J Biol Chem 290: 22678–22685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkuni K, Takahashi Y, Fulp A, Lawrimore J, Au WC, Pasupala N, Levy-Myers R, Warren J, Strunnikov A, Baker RE, et al. 2016. SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase (STUbL) Slx5 regulates proteolysis of centromeric histone H3 variant Cse4 and prevents its mislocalization to euchromatin. Mol Biol Cell 27: 1500–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. 1997. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol 276: 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prudden J, Pebernard S, Raffa G, Slavin DA, Perry JJ, Tainer JA, McGowan CH, Boddy MN. 2007. SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligases in genome stability. EMBO J 26: 4089–4101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabitsch KP, Petronczki M, Javerzat JP, Genier S, Chwalla B, Schleiffer A, Tanaka TU, Nasmyth K. 2003. Kinetochore recruitment of two nucleolar proteins is required for homolog segregation in meiosis I. Dev Cell 4: 535–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reindle A, Belichenko I, Bylebyl GR, Chen XL, Gandhi N, Johnson ES. 2006. Multiple domains in Siz SUMO ligases contribute to substrate selectivity. J Cell Sci 119: 4749–4757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin GM, Sulston JE. 1973. Physical linkage of the 5 S cistrons to the 18 S and 28 S ribosomal RNA cistrons in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Mol Biol 79: 521–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Shenoy RT, Dalgaard JZ, Newnham L, Hoffmann E, Millar JB, Arumugam P. 2013. Monopolin subunit Csm1 associates with MIND complex to establish monopolar attachment of sister kinetochores at meiosis I. PLoS Genet 9: e1003610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer E, MacKechnie C, Halvorson HO. 1969. The redundancy of ribosomal and transfer RNA genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Mol Biol 40: 261–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shou W, Seol JH, Shevchenko A, Baskerville C, Moazed D, Chen ZW, Jang J, Shevchenko A, Charbonneau H, Deshaies RJ. 1999. Exit from mitosis is triggered by Tem1-dependent release of the protein phosphatase Cdc14 from nucleolar RENT complex. Cell 97: 233–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Durrin LK, Wilkinson TA, Krontiris TG, Chen Y. 2004. Identification of a SUMO-binding motif that recognizes SUMO-modified proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci 101: 14373–14378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikumar T, Lewicki MC, Raught B. 2013. A global S. cerevisiae small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) system interactome. Mol Syst Biol 9: 668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straight AF, Shou W, Dowd GJ, Turck CW, Deshaies RJ, Johnson AD, Moazed D. 1999. Net1, a Sir2-associated nucleolar protein required for rDNA silencing and nucleolar integrity. Cell 97: 245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Leverson JD, Hunter T. 2007. Conserved function of RNF4 family proteins in eukaryotes: targeting a ubiquitin ligase to SUMOylated proteins. EMBO J 26: 4102–4112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Dulev S, Liu X, Hiller NJ, Zhao X, Strunnikov A. 2008. Cooperation of sumoylated chromosomal proteins in rDNA maintenance. PLoS Genet 4: e1000215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Prelich G. 2009. Quality control of a transcriptional regulator by SUMO-targeted degradation. Mol Cell Biol 29: 1694–1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waples WG, Chahwan C, Ciechonska M, Lavoie BD. 2009. Putting the brake on FEAR: Tof2 promotes the biphasic release of Cdc14 phosphatase during mitotic exit. Mol Biol Cell 20: 245–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann S, Drubin DG, Barnes G. 2007. Structures and functions of yeast kinetochore complexes. Annu Rev Biochem 76: 563–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AG, McCoy A, et al. 2011. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67: 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlschlegel JA, Johnson ES, Reed SI, Yates JR III. 2006. Improved identification of SUMO attachment sites using C-terminal SUMO mutants and tailored protease digestion strategies. J Proteome Res 5: 761–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Kerscher O, Kroetz MB, McConchie HF, Sung P, Hochstrasser M. 2007. The yeast Hex3.Slx8 heterodimer is a ubiquitin ligase stimulated by substrate sumoylation. J Biol Chem 282: 34176–34184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Rubenstein EM, Matt T, Hochstrasser M. 2010. SUMO-independent in vivo activity of a SUMO-targeted ubiquitin ligase toward a short-lived transcription factor. Genes Dev 24: 893–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Blobel G. 2005. A SUMO ligase is part of a nuclear multiprotein complex that affects DNA repair and chromosomal organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 4777–4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Ryan JJ, Zhou H. 2004. Global analyses of sumoylated proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Induction of protein sumoylation by cellular stresses. J Biol Chem 279: 32262–32268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.