Abstract

Essential oils are one of the most notorious natural products used for medical purposes. Combined with their popular use in dermatology, their availability, and the development of antimicrobial resistance, commercial essential oils are often an option for therapy. At least 90 essential oils can be identified as being recommended for dermatological use, with at least 1500 combinations. This review explores the fundamental knowledge available on the antimicrobial properties against pathogens responsible for dermatological infections and compares the scientific evidence to what is recommended for use in common layman's literature. Also included is a review of combinations with other essential oils and antimicrobials. The minimum inhibitory concentration dilution method is the preferred means of determining antimicrobial activity. While dermatological skin pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus have been well studied, other pathogens such as Streptococcus pyogenes, Propionibacterium acnes, Haemophilus influenzae, and Brevibacterium species have been sorely neglected. Combination studies incorporating oil blends, as well as interactions with conventional antimicrobials, have shown that mostly synergy is reported. Very few viral studies of relevance to the skin have been made. Encouragement is made for further research into essential oil combinations with other essential oils, antimicrobials, and carrier oils.

1. Introduction

The skin is the body's largest mechanical barrier against the external environment and invasion by microorganisms. It is responsible for numerous functions such as heat regulation and protecting the underlying organs and tissue [1, 2]. The uppermost epidermal layer is covered by a protective keratinous surface which allows for the removal of microorganisms via sloughing off of keratinocytes and acidic sebaceous secretions. This produces a hostile environment for microorganisms. In addition to these defences, the skin also consists of natural microflora which offers additional protection by competitively inhibiting pathogenic bacterial growth by competing for nutrients and attachment sites and by producing metabolic products that inhibit microbial growth. The skin's natural microflora includes species of Corynebacterium, staphylococci, streptococci, Brevibacterium, and Candida as well as Propionibacterium [3–8].

In the event of skin trauma from injuries such as burns, skin thinning, ulcers, scratches, skin defects, trauma, or wounds, the skin's defence may be compromised, allowing for microbial invasion of the epidermis resulting in anything from mild to serious infections of the skin. Common skin infections caused by microorganisms include carbuncles, furuncles, cellulitis, impetigo, boils (Staphylococcus aureus), folliculitis (S. aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa), ringworm (Microsporum spp., Epidermophyton spp., and Trichophyton spp.), acne (P. acnes), and foot odour (Brevibacterium spp.) [3, 8–11]. Environmental exposure, for example, in hospitals where nosocomial infections are prominent and invasive procedures make the patient vulnerable, may also create an opportunity for microbial infection. For example, with the addition of intensive therapy and intravascular cannulae, S. epidermidis can enter the cannula and behave as a pathogen causing bloodborne infections. Noninfective skin diseases such as eczema can also result in pathogenic infections by damaging the skin, thus increasing the risk of secondary infection by herpes simplex virus and/or S. aureus [5, 8, 12].

Skin infections constitute one of the five most common reasons for people to seek medical intervention and are considered the most frequently encountered of all infections. At least six million people worldwide are affected by chronic wounds and up to 17% of clinical visits are a result of bacterial skin infections and these wounds are a frequent diagnosis for hospitalised patients. These are experienced daily and every doctor will probably diagnose at least one case per patient. Furthermore, skin diseases are a major cause of death and morbidity [8, 13, 14]. The healing rate of chronic wounds is affected by bacterial infections (such as S. aureus, E. coli, and P. aeruginosa), pain, inflammation, and blood flow, and thus infection and inflammation control may assist in accelerating healing [15–17].

Topical skin infections typically require topical treatment; however, due to the ability of microbes to evolve and due to the overuse and incorrect prescribing of the current available conventional antimicrobials, there has been emergence of resistance in common skin pathogens such as S. aureus resulting as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and other such strains. Treatment has therefore become a challenge and is often not successful [8, 18, 19]. In some regions of the world, infections are unresponsive to all known antibiotics [20]. This threat has become so severe that simple ulcers now require treatment with systemic antibiotics [21]. A simple cut on the finger or a simple removal of an appendix could result in death by infection. The World Health Organization (WHO) has warned that common infections may be left without a cure as we are headed for a future without antibiotics [22]. Therefore, one of the solutions available is to make use of one of the oldest forms of medicine, natural products, to treat skin infections and wounds [18, 23].

Complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) are used by 60–80% of developing countries as they are one of the most prevalent sources of medicine worldwide [24–27]. Essential oils are also one of the most popular natural products, with one of their main applications being for their use in dermatology [28–30]. In fact, of all CAMs, essential oils are the most popular choice for treating fungal skin infections [13, 31]. Their use in dermatology, in the nursing profession, and in hospitals has been growing with great popularity worldwide, especially in the United States and the United Kingdom [1, 27, 32–35]. Furthermore, the aromatherapeutic literature [1, 2, 26, 32, 36–43] identifies numerous essential oils for dermatological use, the majority of which are recommended for infections. This brought forth the question as to the efficacy of commercial essential oils against the pathogens responsible for infections. The aim of this review was to collect and summarise the in vivo, in vitro, and clinical findings of commercial essential oils that have been tested against infectious skin diseases and their pathogens and, in doing so, offer aromatherapists and dermatologists valuable information regarding the effectiveness of essential oils for dermatological infections.

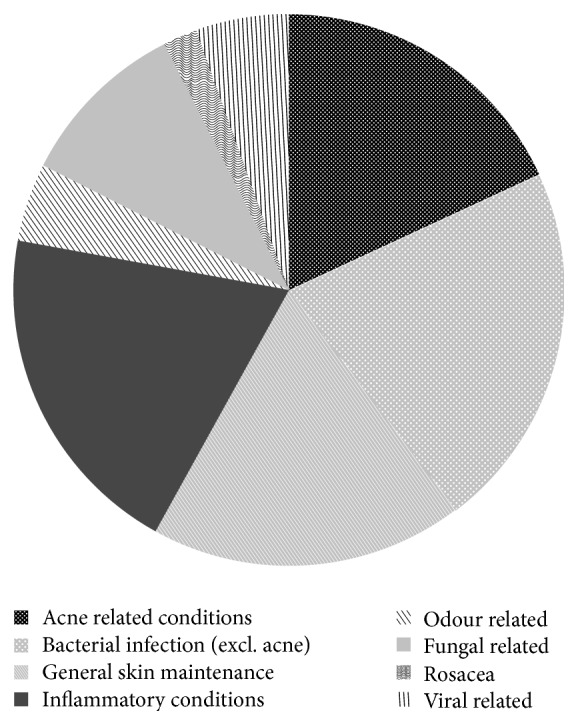

The readily available aromatherapeutic literature has reported over 90 (Table 1) commercial essential oils that may be used for treating dermatological conditions [1, 2, 26, 32, 36–43]. An overview of the skin related uses can be seen in Figure 1. Essential oils are mostly used for the treatment of infections caused by bacteria, fungi, or viruses (total 62%). This is followed by inflammatory skin conditions (20%) such as dermatitis, eczema, and lupus and then general skin maintenance (18%) such as wrinkles, scars, and scabs, which are the third most common use of essential oils. Other applications include anti-inflammatory and wound healing applications (Figure 1). Of the 98 essential oils recommended for dermatological use, 88 are endorsed for treating skin infections. Of these, 73 are used for bacterial infections, 49 specifically for acne, 34 for fungal infections, and 16 for viral infections.

Table 1.

Essential oils used in dermatology.

| Scientific name | Common name | Dermatological use | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abies balsamea | Balsam (Peru, Canadian) | Burns ∗, cracks, cuts, eczema, rashes, sores, and wounds | [32] |

|

| |||

| Abies balsamea | Fir | Skin tonic | [36] |

|

| |||

| Acacia dealbata | Mimosa | Antiseptic, general care, oily conditions, and nourisher | [2, 32] |

|

| |||

| Acacia farnesiana | Cassie | Dry or sensitive conditions | [32] |

|

| |||

| Achillea millefolium | Yarrow | Acne, burns, chapped skin, cuts, dermatitis, eczema, healing agent, infections, inflammation, oily conditions, pruritus, rashes, scars, toner, sores, ulcers, and wounds | [32, 36, 40, 42] |

|

| |||

| Allium sativum | Garlic | Acne, antiseptic, fungal infections (ringworm), lupus, septic wounds, and ulcers | [32, 36] |

|

| |||

| Amyris balsamifera | Amyris | Inflammation | [36] |

|

| |||

| Anethum graveolens | Dill | Wound healing encouragement | [36] |

|

| |||

| Angelica archangelica | Angelica | Congested and dull conditions, fungal infections, inflammation, psoriasis, and tonic | [32, 36] |

|

| |||

| Aniba rosaeodora | Rosewood | Acne, congested conditions, cuts, damaged skin, dermatitis, general care, greasy and oily conditions, inflammation, psoriasis, scars, regeneration, sores, wounds, and wrinkles | [2, 32, 36, 37, 39, 41, 42] |

|

| |||

| Anthemis nobilis | Roman chamomile | Abscesses, acne, allergies, antiseptic, blisters, boils, burns, cleanser, cuts, dermatitis, eczema, foot blisters, general care, herpes, inflammation, insect bites and stings, nappy rash, nourisher, problematic skin, pruritus, psoriasis, rashes, rosacea, sores, sunburn, ulcers, and wounds | [2, 26, 32, 36–43] |

|

| |||

| Apium graveolens | Celery | Reducing puffiness and redness | [36] |

|

| |||

| Artemisia dracunculus | Tarragon | Infectious wounds | [36] |

|

| |||

| Betula alba | Birch (white) | Congested conditions, dermatitis, eczema, psoriasis, and ulcers | [32, 36] |

|

| |||

| Boswellia carteri | Frankincense/olibanum | Abscesses, acne, aged or dry and damaged complexions, antiseptic, bacterial infections, blemishes, carbuncles, dermatitis, disinfectant, eczema, fungal and nail infections, general care, healing agent, inflammation, oily conditions, psoriasis, problematic conditions, regeneration or rejuvenation, scars, sores, toner, tonic, ulcers, wounds, and wrinkles | [1, 2, 32, 36–43] |

|

| |||

| Bursera glabrifolia | Linaloe (copal) | Acne, conditioning, cuts, dermatitis, sores, and wounds | [32, 40] |

|

| |||

| Calendula officinalis | Marigold | Athlete's foot, burns, cuts, diaper rash, eczema, fungal infections, inflammation, oily and greasy conditions, and wounds | [26, 32, 39] |

|

| |||

| Cananga odorata | Ylang-ylang | Acne, balancing sebum, dermatitis, eczema, general care, greasy and oily conditions, insect bites, and toner | [2, 32, 36–38, 40, 42, 43] |

|

| |||

| Canarium luzonicum | Elemi | Aged and dry complexions, bacterial infections, balancing sebum, cuts, fungal infections, inflammation, sores, ulcers, wounds, and wrinkles | [32, 36, 40] |

|

| |||

| Carum carvi | Caraway | Acne, boils, infected wounds, oily conditions, and pruritus | [36] |

|

| |||

| Cedrus atlantica | Cedar wood | Acne, antiseptic, ∗bromodosis, cellulite, cracked skin, dandruff, dermatitis, eczema, eruptions, fungal infections, general care, genital infections, greasy and oily conditions, inflammation, insect bites and stings, psoriasis, scabs, and ulcers | [1, 2, 32, 36–39, 41–43] |

|

| |||

| Cinnamomum camphora | Camphor (white) | Acne, burns, inflammation, oily conditions, spots, and ulcers | [32, 36, 42] |

|

| |||

| Cinnamomum zeylanicum | Cinnamon | Antiseptic, gum and tooth care, warts, and wasp stings | [32, 36, 37, 41, 42] |

|

| |||

| Cistus ladanifer | Rock rose/Cistus/labdanum | Aged complexion, bacterial infections, bedsores, blocked pores, eczema, oily conditions, sores, ulcers, varicose ulcers, wounds, and wrinkles | [2, 32, 40] |

|

| |||

| Citrus aurantifolia | Lime | Acne, bacterial infections, boils, cellulite, congested or greasy and oily conditions, cuts, insect bites, pruritus, tonic, sores, ulcers, warts, and wounds | [2, 32, 36, 40–43] |

|

| |||

| Citrus aurantium var. amara | Neroli | Acne, aged and dry complexions, antiseptic, broken capillaries, cuts, dermatitis, eczema, general care, healing agent, psoriasis, scars, stretch marks, toner, tonic, thread veins, wounds, and wrinkles | [2, 26, 32, 36–43] |

|

| |||

| Citrus aurantium var. amara | Petitgrain | Acne, antiseptic, bacterial infections, balancing sebum, blemishes, greasy and oily conditions, ∗∗ hyperhidrosis, pimples, pressure sores, sensitive complexions, toner, tonic, and wounds | [1, 2, 32, 36, 37, 39–42] |

|

| |||

| Citrus bergamia | Bergamot | Abscesses, acne, antiseptic, athlete's foot, bacterial infections, blisters, boils, cold sores, deodorant, dermatitis, eczema, fungal infections, greasy and oily conditions, healing agent, inflammation, insect bites, pruritus, psoriasis, shingles, ulcers, viral infections (chicken pox, herpes, and shingles), and wounds | [2, 26, 32, 36, 37, 40–43] |

|

| |||

| Citrus limon | Lemon | Abscesses, acne, antiseptic, athlete's foot, blisters, boils, cellulite, corns, cuts, grazes, greasy and oily conditions, insect bites, mouth ulcers, rosacea, sores,ulcers, viral infections (cold sores, herpes, verrucae,and warts), and wounds | [1, 2, 26, 32, 36, 37, 39, 41–43] |

|

| |||

| Citrus paradisi | Grapefruit | Acne, antiseptic, cellulite improvement, cleanser, combination and problematic skin, congested and oily conditions, stretch marks, and toner | [1, 2, 32, 36, 37, 39–43] |

|

| |||

| Citrus reticulata | Mandarin | Acne, cellulite, congested and oily conditions, general care, healing agent, scars, stretch marks, and toner | [1, 32, 36–38, 40, 43] |

|

| |||

| Citrus sinensis | Orange | Acne, blocked pores, congested and oily conditions, dermatitis, dry and dull complexions, problematic skin, ulcers, and wrinkles | [1, 32, 36–38, 40–43] |

|

| |||

| Citrus tangerina | Tangerine | Acne, chapped skin, inflammation, oily conditions, rashes, stretch marks, and toner | [36, 40, 42] |

|

| |||

| Commiphora myrrha | Myrrh | Acne, antiseptic, athlete's foot, bacterial infections, bedsores, boils, cracked skin, cuts, dermatitis, eczema, fungal infections (athlete's foot, ringworm), healing agent, inflammation, scars, sores, ulcers, weeping wounds, and wrinkles | [1, 2, 26, 32, 36–43] |

|

| |||

| Coriandrum sativum | Coriander | Used to prevent the growth of odour causing bacteria | [37] |

|

| |||

| Cupressus sempervirens | Cypress | Acne, blocked pores, bromodosis, cellulite, cellulitis, deodorant, hyperhidrosis, oily conditions, rashes, rosacea, and wounds | [1, 2, 32, 36–38, 40–43] |

|

| |||

| Curcuma longa | Turmeric | Cuts, sores, and wounds | [40] |

|

| |||

| Cymbopogon citratus | Lemongrass | Acne, athlete's foot, bacterial infections, blocked or open pores, cellulite, fungal infections, hyperhidrosis, oily conditions, and toner | [2, 32, 36, 37, 41, 42] |

|

| |||

| Cymbopogon martinii | Palmarosa | Acne, bacterial infections, balancing sebum, damaged and dry complexions, dermatitis, eczema, fungal infections, oily conditions, pressure sores, psoriasis, scars, toner, tonic, sores, wounds, and wrinkles | [2, 32, 36–42] |

|

| |||

| Cymbopogon nardus | Citronella | Bromodosis, hyperhidrosis, oily conditions, and softener | [32, 36, 42] |

|

| |||

| Daucus carota | Carrot seed | Aged and dry complexions, carbuncles, dermatitis, eczema, inflammation, oily conditions, pruritus, psoriasis, rashes, scarring, toner, ulcers, vitiligo, weeping sores, wounds, and wrinkles | [2, 32, 36, 40, 42] |

|

| |||

| Dryobalanops aromatica | Borneol (Borneo Camphor) | Cuts and sores | [32] |

|

| |||

| Eucalyptus globulus | Eucalyptus | Abscesses, antiseptic, athlete's foot, bacterial dermatitis, bacterial infections, blisters, boils, burns, chicken pox, cleanser, congested conditions, cuts, fungal infections, general infections, herpes (cold sores), inflammation, insect bites, shingles, sores, ulcers, and wounds | [1, 26, 32, 36–39, 41–43] |

|

| |||

| Syzygium aromaticum | Clove | Acne, antiseptic, athlete's foot, burns, cuts, cold sores, fungal infections, lupus, sores, septic ulcers, and wounds | [32, 36, 37, 41, 42] |

|

| |||

| Ferula galbaniflua | Galbanum | Abscesses, acne, blisters, boils, cuts, inflammation, scar tissue improvement, toner, and wounds | [32, 36] |

|

| |||

| Foeniculum dulce | Fennel | Aged and wrinkled complexions, bromodosis, cellulite, cellulitis, congested, greasy, and oily conditions, cleanser, and tonic | [1, 32, 36, 37, 40–43] |

|

| |||

| Guaiacum officinale | Guaiacwood | Firming or tightening the skin | [36] |

|

| |||

| Helichrysum italicum | Immortelle/everlasting/Helichrysum | Abscesses, acne, athlete's foot, bacterial infections, boils, blisters, cell regeneration, cuts, damaged skin conditions, dermatitis, eczema, fungal infections (ringworm), inflammation, psoriasis, rosacea, scars, sores, ulcers, and wounds | [2, 32, 36, 40, 41] |

|

| |||

| Humulus lupulus | Hops | Dermatitis, ulcers, rashes, and nourisher | [32] |

|

| |||

| Hyssopus officinalis | Hyssop | Cuts, dermatitis, eczema, healing agent, inflammation, scars, sores, and wounds | [32, 36, 41] |

|

| |||

| Jasminum officinale | Jasmine | Aged and dry complexions, general care, inflammation, revitalization, oily conditions, and psoriasis | [2, 26, 32, 36, 37, 40] |

|

| |||

| Juniperus virginiana | Juniper | Acne, antiseptic, blocked pores, cellulite, congested and oily conditions, deodorant, eczema, dermatitis, general care, general infections, psoriasis, toner, ulcers, weeping eczema, and wounds | [1, 2, 32, 36, 37, 39, 41–43] |

|

| |||

| Juniperus oxycedrus | Cade | Cuts, dermatitis, eczema, sores, and spots | [32] |

|

| |||

| Kunzea ericoides | Kānuka | Athlete's foot | [40] |

|

| |||

| Laurus nobilis | Bay | Acne, fungal infections, inflammation, oily conditions, pressure sores, and varicose ulcers | [32, 36, 41] |

|

| |||

| Lavandula angustifolia | Lavender | Abscesses, acne, antiseptic, bacterial infections, blisters, boils, burns, carbuncles, cellulite, congested and oily conditions, cuts, deodorant, dermatitis, eczema, foot blisters, fungal infections (athlete's foot, ringworm), general care, healing agent, inflammation, insect bites and stings, pressure sores, pruritus, psoriasis, rosacea, scalds, scarring, sores, sunburn, ulcers,viral infections (chicken pox, cold sores, shingles,and warts), and wounds | [2, 26, 32, 36–43] |

|

| |||

| Lavandula flagrans | Lavandin | Acne, abscesses, boils, blisters, congested conditions, cuts, eczema, healing agent, inflammation, insect bites and stings, pressure sores, scalds, sores, and wounds | [32, 36, 41] |

|

| |||

| Lavandula spica | Lavender spike | Abscesses, acne, bacterial infections, blisters, boils, burns, congested and oily conditions, cuts, dermatitis, eczema, inflammation, fungal infections (athlete's foot, ringworm), pressure sores, psoriasis, sores, ulcers, and wounds | [32, 36, 41] |

|

| |||

| Leptospermum scoparium | Manuka | Acne, cuts, fungal infections (athlete's foot, ringworm), ulcers, and wounds | [2, 40] |

|

| |||

| Verbena officinalis | Verbena | Congested conditions and nourisher | [36] |

|

| |||

| Liquidambar orientalis | Sweetgum | Cuts, ringworm, sores, and wounds | [32] |

|

| |||

| Litsea cubeba | May Chang | Acne, dermatitis, greasy and oily conditions, and hyperhidrosis | [32, 36] |

|

| |||

| Melaleuca alternifolia | Tea tree | Abrasions, abscesses, acne, antiseptic, bacterial infections, blemishes, blisters, boils, burns, carbuncles, cuts, dandruff, fungal infections (athlete's foot, nails, ringworm, and tinea), inflammation, insect bites, oily conditions, rashes, sores, spots, sunburn, ulcers, viral infections (cold sores, chicken pox, herpes, shingles,and warts), and wounds | [1, 2, 26, 32, 36–43] |

|

| |||

| Melaleuca cajuputi | Cajuput | Acne, insect bites, oily conditions, psoriasis, and spots | [32, 36, 42] |

|

| |||

| Melaleuca viridiflora | Niaouli/Gomenol | Abscesses, acne, antiseptic, bacterial infections, blisters, boils, burns, chicken pox, congested and oily conditions, cuts, eruptions, healing agent, insect bites, psoriasis, sores, ulcers, and wounds | [2, 32, 36, 39–42] |

|

| |||

| Melissa officinalis | Melissa/lemon balm | Allergic reactions, cold sores, eczema, fungal infections, inflammation, insect stings, ulcers, and wounds | [1, 26, 32, 36, 41, 42] |

|

| |||

| Mentha piperita | Peppermint | Acne, antiseptic, blackheads, chicken pox, congested and greasy conditions, dermatitis, inflammation, pruritus, ringworm, scabies, softener, toner, and sunburn | [1, 2, 32, 36, 37, 41–43] |

|

| |||

| Mentha spicata | Spearmint | Acne, congested conditions, dermatitis, pruritus, scabs, and sores | [32, 36, 39, 42] |

|

| |||

| Myristica fragrans | Nutmeg | Hair conditioner | [36] |

|

| |||

| Myrocarpus fastigiatus | Cabreuva | Cuts, scars, and wounds | [32] |

|

| |||

| Myrtus communis | Myrtle | Acne, antiseptic, blemishes, blocked pores, bruises, congested and oily conditions, and psoriasis | [2, 32, 36, 40] |

|

| |||

| Nardostachys jatamansi | Spikenard | Eczema, inflammation, psoriasis, and sores | [32, 40] |

|

| |||

| Ocimum basilicum | Basil | Acne, antiseptic, congested conditions, insect bites, and wasp stings | [1, 36, 37, 39, 40, 42] |

|

| |||

| Origanum majorana | Marjoram | Bruises and fungal infections | [32, 36] |

|

| |||

| Origanum vulgare | Oregano | Athlete's foot, bacterial infections, cuts, eczema, fungal infections, psoriasis, warts, and wounds | [36, 41] |

|

| |||

| Pelargonium odoratissimum | Geranium | Acne, aged and dry complexions, bacterial infections, balancing sebum, burns, cellulite, chicken pox, congested and oily conditions, cracked skin, cuts, dermatitis, deodorant, eczema, fungal infections (athlete's foot, ringworm), general care, healing agent, herpes, impetigo, inflammation, measles, psoriasis, rosacea, shingles, problematic skin, sores, ulcers, and wounds | [2, 26, 32, 36–43] |

|

| |||

| Pelargonium roseum | Rose geranium | Aging and dry or wrinkled skin | [40] |

|

| |||

| Petroselinum sativum | Parsley | Bruises, scalp conditioning, and wounds | [36] |

|

| |||

| Pimpinella anisum | Anise | Infectious diseases | [36] |

|

| |||

| Pinus sylvestris | Pine | Antiseptic, bromodosis, congested conditions, cuts, eczema, hyperhidrosis, pruritus, psoriasis, and sores | [32, 36, 37, 41–43] |

|

| |||

| Piper nigrum | Black pepper | Bruises and fungal infections | [36, 42] |

|

| |||

| Pistacia lentiscus | Mastic | Abscesses, blisters, boils, cuts, ringworm, and wounds | [32] |

|

| |||

| Pistacia palaestina | Terebinth | Abscesses, blisters, boils, cuts, infectious wounds, ringworm, and sores | [32, 36] |

|

| |||

| Pogostemon patchouli | Patchouli | Abscesses, acne, chapped or damaged and cracked skin, dermatitis, cold sores, eczema, fungal infections (athlete's foot), general care, healing agent, impetigo, inflammation, oily conditions, pruritus, scalp disorders, scars, sores, tonic, stretch marks, and wounds | [1, 2, 32, 36–43] |

|

| |||

| Rosa damascena | Rose otto | Aging and dry conditions, bacterial infections, eczema, inflammation, toner, tonic, and wounds | [2, 38–41] |

|

| |||

| Rosa gallica | Rose | Broken capillaries, cuts, dry and aging conditions, burns, eczema, healing agent, inflammation, pruritus, psoriasis, scars, toner, tonic, stretch marks, sunburn, thread veins, and wrinkles | [26, 32, 36–38, 42, 43] |

|

| |||

| Rosmarinus officinalis | Rosemary | Acne, bacterial infections, balancing sebum, cellulite, congested and oily conditions, dandruff, dermatitis, dry scalp, eczema, general care, and rosacea | [1, 32, 36, 37, 39, 41, 42] |

|

| |||

| Salvia lavandulifolia | Spanish sage | Acne, antiseptic, bacterial infections, cellulite, cold sores, cuts, dermatitis, deodorant, hyperhidrosis, oily conditions, psoriasis, sores, and ulcers | [32, 36, 37, 41] |

|

| |||

| Salvia sclarea | Clary sage | Abscesses, acne, balancing sebum, blisters, boils, cell regeneration, dandruff, dermatitis, greasy and oily conditions, hyperhidrosis of the feet, inflammation, ulcers, and wrinkles | [1, 2, 32, 36, 40, 42] |

|

| |||

| Santalum album | Sandalwood | Acne, antiseptic, bacterial infections, boils, burns, chapped or damaged and dry conditions, eczema, fungal infections, general care, greasy and oily conditions, inflammation, pruritus, sunburn, and wounds | [1, 2, 26, 32, 36–39, 41–43] |

|

| |||

| Santolina chamaecyparissus | Santolina | Inflammation, pruritus, ringworm, scabs, verrucae, and warts | [36] |

|

| |||

| Styrax benzoin | Benzoin | Cracks, cuts, dermatitis, eczema, healing, inflammation, injured and irritated conditions, pruritus, sores, and wounds | [1, 2, 32, 36, 40, 42] |

|

| |||

| Tagetes minuta | Tagetes | Bacterial infections, fungal infections, inflammation, and viral infections (verrucae and warts) | [32, 36, 42] |

|

| |||

| Thymus vulgaris | Thyme | Abscesses, acne, antiseptic, blisters, burns, carbuncles, cellulitis, cuts, deodorant, dermatitis, eczema, fungal infections, oily conditions, sores, and wounds | [1, 32, 36, 37, 41, 42] |

|

| |||

| Tilia europaea | Linden Blossom | Blemishes, burns, freckles, softener, tonic, and wrinkles | [36] |

|

| |||

| Vetiveria zizanioides | Vetiver | Acne, antiseptic, balancing sebum, cuts, eczema, malnourished and aging skin, oily conditions, weeping sores, and wounds | [1, 2, 32, 36, 37, 41, 42] |

|

| |||

| Viola odorata | Violet | Acne, bruises, congested and oily conditions, eczema, inflammation, infections, ulcers, and wounds | [2, 32, 36, 40] |

|

| |||

| Zingiber officinale | Ginger | Bruises, carbuncles, and sores | [36] |

∗Conditions involved in dermatological infections are shown in italics.

∗∗A medical condition that causes excessive sweating.

Figure 1.

Summary of categorised dermatological conditions in which essential oils are used.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Searching Strategy/Selection of Papers

The aim of the comparative review was to identify the acclaimed dermatological commercial essential oils according to the aromatherapeutic literature and then compare and analyse the available published literature. This will serve as a guideline in selecting appropriate essential oils in treating dermatological infections. The analysed papers were selected from three different electronic databases: PubMed, ScienceDirect, and Scopus, accessed during the period 2014–2016. The filters used included either “essential oils”, “volatile oils”, or “aromatherapy” or the scientific or common name for each individual essential oil listed in Table 1 and the additional filters “antimicrobial”, “antibacterial”, “skin”, “infection”, “dermatology”, “acne”, “combinations”, “fungal infections”, “dermatophytes”, “Brevibacteria”, “odour”, “antiviral”, “wounds”, “dermatitis”, “allergy”, “toxicity”, “sentitisation”, or “phototoxicity”.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

In order to effectively understand the possible implications and potential of essential oils, the inclusion criteria were broad, especially with this being the first review to collate this amount of scientific evidence with the aromatherapeutic literature. Inclusion criteria included the following:

Type of in vitro studies for bacterial and fungal pathogens by means of the microdilution assay, macrodilution assay, or the agar dilution assay

In vivo studies

Antiviral studies

Case reports

Animal studies

All clinical trials

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Papers or pieces of information were excluded for the following reasons:

Lack of accessibility to the publication

If the incorrect in vitro technique (diffusion assays) was employed

Indigenous essential oils with no relevance to commercial oils

If they were in a language not understood by the authors of the review

Pathogens studied not relevant to skin disease

2.4. Data Analysis

The two authors (Ané Orchard and Sandy van Vuuren) conducted their own data extraction independently, after which critical analysis was applied. Information was extrapolated and recorded and comments were made. Observations were made and new recommendations were made as to future studies.

3. Results

3.1. Description of Studies

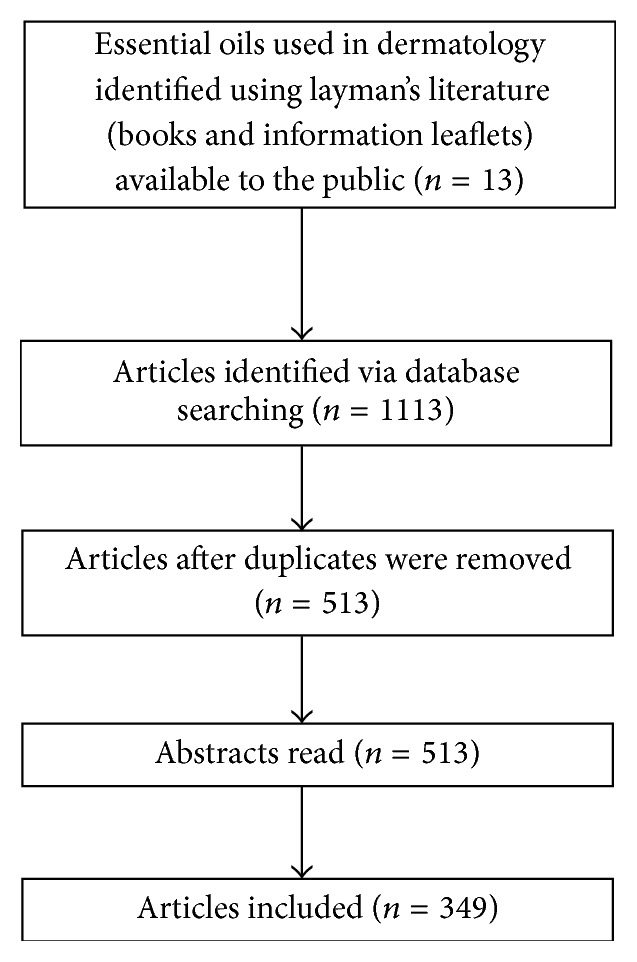

After the initial database search, 1113 reports were screened. Duplicates were removed, which brought the article count down to 513, after which the abstracts were then read and additional reports removed based on not meeting the inclusion criteria. A final number of 349 articles were read and reviewed. Of these, 143 were in vitro bacterial and fungal studies (individual oil and 45 combinations), two in vivo studies, 15 antiviral studies, 19 clinical trials, and 32 toxicity studies. The process that was followed is summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of the review approach.

3.2. Experimental Approaches

3.2.1. Chemical Analysis

Essential oils are complex organic (carbon containing) chemical entities, which are generally made up of hundreds of organic chemical compounds in combination that are responsible for the essential oil's many characteristic properties. These characteristics may include medicinal properties, such as anti-inflammatory, healing, or antimicrobial activities, but may also be responsible for negative qualities such as photosensitivity and toxicity [37].

Even with the high quality grade that is strived for in the commercial sector of essential oil production, it must be noted that it is still possible for essential oil quality to display discrepancies, changes in composition, or degradation. The essential oil composition may even vary between the same species [1, 44]. This may be due to a host of different factors such as the environment or location that the plants are grown in, the harvest season, which part of the plant was used, the process of extracting the essential oil, light or oxygen exposure, the storage of the oil, and the temperature the oil was exposed to [45–51].

Gas chromatography in combination with mass spectrometry (GCMS) is the preferred technique for analysis of essential oils [52]. This is a qualitative and quantitative chemical analysis method which allows for the assurance of the essential oil quality through the identification of individual compounds that make up an essential oil [1, 45, 53]. It has clearly been demonstrated that there is a strong correlation between the chemical composition and antimicrobial activity [51, 54, 55]. Understanding the chemistry of essential oils is essential for monitoring essential oil composition, which then further allows for a better understanding of the biological properties of essential oils. It is recommended to always include the chemical composition in antimicrobial studies [56].

3.3. Antimicrobial Investigations

Several methods exist that may be employed for antimicrobial analysis, with two of the most popular methods being the diffusion and the dilution methods [56–59].

3.3.1. Diffusion Method

There are two types of diffusion assays. Due to the ease of application, the disc diffusion method is one of the most commonly used methods [60]. This is done by applying a known concentration of essential oil onto a sterile filter paper disc. This is then placed onto agar which has previously been inoculated with the microorganism to be tested, or it is spread on the surface. If necessary, the essential oil may also be dissolved in an appropriate solvent. The other diffusion method is the agar diffusion method, where, instead of discs being placed, wells are made in the agar into which the essential oil is instilled. After incubation, antimicrobial activity is then interpreted from the zone of inhibition (measured in millimetres) using the following criteria: weak activity (inhibition zone ≤ 12 mm), moderate activity (12 mm < inhibition zone < 20 mm), and strong activity (inhibition zone ≤ 20 mm) [24, 60–62].

Although this used to be a popular method, it is more suitable to antibiotics rather than essential oils as it does not account for the volatile nature of the essential oils. Essential oils also diffuse poorly through an aqueous medium as they are hydrophobic. Thus, the results are less reliable as they are influenced by the ability of the essential oil to diffuse through the agar medium, resulting in variable results, false negatives, or a reduction in antimicrobial activity [24, 63]. The results have been found to vary significantly when tested this way and are also influenced by other factors such as disc size, amount of compound applied to the disc, type of agar, and the volume of agar [57, 59, 64–68]. It has thus been recommended that results are only considered where the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) or cidal concentration values have been established [65].

3.3.2. Dilution Methods

The dilution assays are reliable, widely accepted, and promising methods for determining an organism's susceptibility to inhibitors. The microdilution method is considered the “gold standard” [64, 68–70]. This is a quantitative method that makes it possible to calculate the MIC and allows one to understand the potency of the essential oil [68, 71]. With one of the most problematic characteristics of essential oils being their volatility, the microdilution technique allows for an opportunity to work around this problem as it allows for less evaporation due to the essential oil being mixed into the broth [67].

This microdilution method makes use of a 96-well microtitre plate under aseptic conditions where the essential oils (diluted in a solvent to a known concentration) are serially diluted. Results are usually read visually with the aid of an indicator dye. The microdilution results can also be interpreted by reading the optical density [72, 73]; however, the shortcoming of this method is that the coloured nature of some oils may interfere with accurate turbidimetric readings [74].

Activity is often classified differently according to the quantitative method followed. van Vuuren [56] recommended 2.00 mg/mL and less for essential oils to be considered as noteworthy, Agarwal et al. [75] regarded 1.00% and less, and Hadad et al. [76] recommended ≤250.00 μg/mL. On considering the collection of data and frequency of certain MIC values, this review recommends MIC values of ≤1.00 mg/mL as noteworthy.

The macrodilution method employs a similar method to that of the microdilution method, except that, instead of a 96-well microtitre plate being used, multiple individual test tubes are used. Although the results are still comparable, this is a time-consuming and a tedious method, whereas the 96-well microtitre plate allows for multiple samples to be tested per plate, allowing for speed, and it makes use of smaller volumes which adds to the ease of its application [77, 78]. The agar dilution method is where the essential oil is serially diluted, using a solvent, into a known amount of sterile molten agar in bottles or tubes and mixed with the aid of a solvent. The inoculum is then added and then the agar is poured into plates for each dilution and then incubated. The absence of growth after incubation is taken as the MIC [79–81].

3.3.3. The Time-Kill Method

The time-kill (or death kinetic) method is a labour intensive assay used to determine the relationship between the concentration of the antimicrobial and the bactericidal activity [82]. It allows for the presentation of a direct relationship in exposure of the pathogen to the antimicrobial and allows for the monitoring of a cidal effect over time [74]. The selected pathogen is exposed to the antimicrobial agent at selected time intervals and aliquots are then sampled and serially diluted. These dilutions are then plated out onto agar and incubated at the required incubation conditions for the pathogen. After incubation, the colony forming units (CFU) are counted. These results are interpreted from a logarithmic plot of the amount of remaining viable cells against time [74, 82, 83]. This is a time-consuming method; however, it is very useful for deriving real-time exposure data.

3.4. Summary of Methods

The variation in essential oil test methods makes it difficult to directly compare results [24, 58]. Numerous studies were found to employ the use of a diffusion method due to its acclaimed “ease” and “time saving” ability of the application. Researchers tend to use this as a screening tool whereby results displaying interesting outcomes are further tested using the microdilution method [84–87]. The shortcoming of this method is that firstly, due to the discussed factors affecting the diffusion methods, certain essential oils demonstrate no inhibition against the pathogen, and thus further studies with the oils are overlooked. Secondly, the active oils are then investigated further using the microdilution method. Therefore, the researchers have now doubled the amount of time required to interpret the quantitative data. Thirdly, the method may be believed to be a faster method if one considers the application; however, if one considers the preparation of the agar plates and their risk of contamination as well as the overall process of this method, there is very little saving of time and effort.

It is recommended to follow the correct guidelines as set out by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute M38-A (CLSI) protocol [88] and the standard method proposed by the Antifungal Susceptibility Testing Subcommittee of the European Committee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing (AFST-EUCAST) [89] for testing with bacteria and filamentous fungi.

Other factors that may affect results and thus make it difficult to compare published pharmacological results of essential oils are where data is not given on the chemical composition, the microbial strain number, temperature and length of incubation, inoculum size, and the solvent used. The use of appropriate solvents helps address the factor of poor solubility of essential oils. Examples include Tween, acetone, dimethylformamide (DMF), dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), and ethanol. Tween, ethanol, and DMSO have, however, been shown to enhance antimicrobial activity of essential oils [24, 53, 90]. Soković et al. [91] tested antimicrobial activity with ethanol as the solvent and Tween. When the essential oils were diluted with Tween, it resulted in a greater antifungal activity; however, Tween itself does not display its own antimicrobial activity [92]. Eloff [93] identified acetone as the most favourable solvent for natural product antimicrobial studies.

The inoculum is a representative of the microorganisms present at the site of infection [94]. When comparing different articles, the bacterial inoculum load ranges from 5 × 102 to 5 × 108 CFU/mL. The antibacterial activity is affected by inoculum size [62, 95–99]. If this concentration is too weak, the effect of the essential oils strengthens; however, this does not allow for a good representation of the essential oil's activity. If the inoculum is too dense, the effect of the essential oil weakens and the inoculum becomes more prone to cross contamination [100]. Future studies should aim to keep the inoculum size at the recommended 5 × 106 CFU/mL [99].

4. Pathogenesis of Wounds and Skin Infections and the Use of Essential Oils

The pathogenesis of the different infections that are frequently encountered in wounds and skin infections is presented in Table 2. A more in-depth analysis of essential oils and their use against these dermatological pathogens follows.

Table 2.

Pathogens responsible for infectious skin diseases.

| Skin disease | Anatomical structure affected by infection | Responsible pathogens | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial infections | |||

| Abscesses | Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Staphylococcus aureus; methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) | [101] |

| Acne | Sebum glands | Propionibacterium acnes; S. epidermidis | [8, 102] |

| Actinomycosis | Skin and subcutaneous tissue | Actinomyces israelii | [5] |

| Boils/carbuncles and furuncles | Hair follicles | S. aureus | [8] |

| Bromodosis (foot odour) | Epidermis/cutaneous | Brevibacterium spp.; P. acnes | [6, 103] |

| Cellulitis | Subcutaneous fat | β-Hemolyticstreptococci; S. aureus; MRSA | [7, 8, 101] |

| Ecthyma | Cutaneous | S. aureus; Streptococcus pyogenes | [7] |

| Erysipelas | Dermis, intradermal | S. pyogenes | [8] |

| Erythrasma | Epidermis | Corynebacterium minutissimum | [5] |

| Folliculitis | Hair follicles | S. aureus; MRSA | [8, 101] |

| Impetigo | Epidermis | S. pyogenes; S. aureus | [8, 104, 105] |

| Periorbital cellulitis | Subcutaneous fat | Haemophilus influenzae | [106] |

| Surgical wounds | Skin, fascia, and subcutaneous tissue | Escherichia coli; Enterococcus spp.; Pseudomonas aeruginosa; S. aureus | [8] |

|

| |||

| Necrotizing infections | |||

| Necrotizing fasciitis | Skin, fascia, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle | S. pyogenes; anaerobic pathogens | [5, 8, 107] |

| Gas forming infections | Skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle | Gram-negative and various anaerobes | [5] |

| Gas gangrene | Skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle | Clostridium spp. (C. perfringens, C. septicum, C. tertium, C. oedematiens, and C. histolyticum) | [5, 8, 107] |

|

| |||

| Fungal infections | |||

| Candidal infections (intertrigo, balanitis, nappy rash, angular cheilitis, and paronychia) | Superficial skin | Candida albicans | [7] |

| Eumycetoma | Subcutaneous infection | Madurella mycetomatis | [108] |

| Dermatophytosis (tinea pedis/athlete's foot, tinea cruris, tinea capitis, tinea corporis, tinea manuum, and tinea unguium/onychomycosis) | Keratin layer, epidermis | Dermatophytes (Microsporum, Epidermophyton, and Trichophyton spp.) | [8] |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | Subcutaneous infection | Malasseziafurfur | [109] |

| Tinea/pityriasis versicolor | Superficial skin | M. furfur | [7, 110] |

|

| |||

| Viral infections | |||

| Herpes simplex | Mucocutaneous epidermidis | Herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1, orofacial disease; HSV type 2, genital infection | [7] |

| Chicken pox | Mucocutaneous epidermidis | Varicella zoster | |

| Molluscum contagiosum | Prickle cells of epidermidis | Poxvirus | |

| Shingles | Mucocutaneous epidermidis | Herpes zoster | |

|

| |||

| Warts and verrucae | Epidermis | Human papillomavirus | [5, 7] |

4.1. Gram-Positive Bacteria

The Gram-positive bacterial cell wall is comprised of a 90–95% peptidoglycan layer that allows for easy penetration of lipophilic molecules into the cells. This thick lipophilic cell wall also results in essential oils making direct contact with the phospholipid bilayer of the cell membrane which allows for a physiological response to occur on the cell wall and in the cytoplasm [183, 184].

4.1.1. Staphylococcus aureus

Staphylococcus aureus is a common Gram-positive bacterium that can cause anything from local skin infections to fatal deep tissue infections. The pathogen is also found colonising acne and burn wounds [185–187]. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) is one of the most well-known and widespread “superbugs” and is resistant to numerous antibiotics [158]. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus strains can be found to colonise the skin and wounds of over 63%–90% of patients and have been especially infamous as being the dreaded scourge of hospitals for several years [22, 188–190]. Staphylococcus aureus has developed resistance against erythromycin, quinolones, mupirocin, tetracycline, and vancomycin [190–192].

Table 3 shows some of the antimicrobial in vitro studies undertaken on commercial essential oils and additional subtypes against this most notorious infectious agent of wounds. Of the 98 available commercial essential oils documented from the aromatherapeutic literature for use for dermatological infections, only 54 oils have been tested against S. aureus and even fewer against the resistant S. aureus strain. This is troubling, especially if one considers the regularity of S. aureus resistance. It should be recommended that resistant S. aureus strains always be included with every study.

Table 3.

Essential oil studies against S. aureus.

| Essential oila | Methodb | Species strainc | Solventd | Resulte | Main componentsf | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abies balsamea (fir/balsam) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 3.00 mg/mL | β-Pinene (31.00%), bornyl acetate (14.90%), δ-3-carene (14.20%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Abies holophylla (Manchurian fir) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | 5% DMSO | 21.80 mg/mL | Bicyclo[2.2.1]heptan-2-ol (28.05%), δ-3-carene (13.85%), α-pinene (11.68%), camphene (10.41%) | [111] |

| S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | >21.80 mg/mL | |||||

| Abies koreana (Korean fir) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | 5% DMSO | 21.80 mg/mL | Bornyl ester (41.79%), camphene (15.31%), α-pinene (11.19%) | |

| S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | >21.80 mg/mL | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Achillea millefolium (yarrow) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | Tween 80 | 72.00 mg/mL | Eucalyptol (24.60%), camphor (16.70%), α-terpineol (10.20%) | [112] |

|

| ||||||

| Achillea setacea (bristly yarrow) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | Tween 80 | 4.50 mg/mL | Sabinene (10.80%), eucalyptol (18.50%) | [113] |

|

| ||||||

| Angelica archangelica (angelica), root | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 1.75 mg/mL | α-Phellandrene (18.50%), α-pinene (13.70%), β-phellandrene (12.60%), δ-3-carene (12.1%) | [99] |

| Angelica archangelica (angelica), seed | 2.00 mg/mL | β-Phellandrene (59.20%) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Anthemis aciphylla var. discoidea (chamomile), flowers | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | DMSO | 1.00 mg/mL | α-Pinene (39.00%), terpinen-4-ol (32.10%) | [114] |

| Anthemis aciphylla var. discoidea (chamomile), aerial parts | 0.50 mg/mL | α-Pinene (49.40%), terpinen-4-ol (21.80%) | ||||

| Anthemis aciphylla var. discoidea (chamomile), leaves | Terpinen-4-ol (24.30%) | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Anthemis nobilis (chamomile) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 16.00 mg/mL | 2-Methylbutyl-2-methyl propanoic acid (31.50%), limonene (18.30%), 3-methylpentyl-2-butenoic acid (16.70%), isobutyl isobutyrate (10.00%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Artemisia dracunculus (tarragon) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 3.00 mg/mL | Estragole (82.60%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Backhousia citriodora (lemon myrtle) | ADM | S. aureus (NCTC 4163) | Tween 20 | 0.05% v/v | Geranial (51.40%), neral (40.90%) | [115] |

| MRSA (clinical isolate) | 0.20% v/v | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Boswellia carteri (frankincense) (9 samples) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 12600) | Acetone | 5.00–16.00 mg/mL | α-Pinene (4.80–40.40%), myrcene (1.60–52.40%), limonene (1.90–20.40%), α-thujene (0.30–52.40%), p-cymene (2.70–16.90%), β-pinene (0.30–13.10%) | [116] |

| Boswellia frereana (frankincense) (3 samples) | 4.00–12.00 mg/mL | α-Pinene (2.00–64.70%), α-thujene (0.00–33.10%), p-cymene (5.40–16.90%) | ||||

| Boswellia neglecta (frankincense) | 6.00 mg/mL | NCR | [117] | |||

| α-Pinene (43.40%), β-pinene (13.10%) | [116] | |||||

| Boswellia papyrifera (frankincense) | 1.50 mg/mL | NCR | [117] | |||

| Boswellia rivae (frankincense) | 2.50 mg/mL | |||||

| Boswellia sacra (frankincense) (2 samples) | 4.00–8.00 mg/mL | α-Pinene (18.30–28.00%), α-thujene (3.90–11.20%), limonene (11.20–13.10%) | [116] | |||

| Boswellia spp. (frankincense) (4 samples) | 6.00–9.30 mg/mL | α-Pinene (18.80–24.20%), limonene (11.70–19.00%) | ||||

| Boswellia thurifera (frankincense) | 10.00 mg/mL | α-Pinene (28.0%), limonene (14.6%) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Cananga odorata (ylang-ylang) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | Bicyclosesquiphellandrene (19.50%), β-farnesene (13.90%) | [99] |

| Cananga odorata (ylang-ylang), heads | 4.00 mg/mL | Benzyl acetate (31.90%), linalool (27.00%), methyl benzoate (10.40%) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Canarium luzonicum (elemi) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 3.00 mg/mL | Limonene (41.90%), elemol (21.60%), α-phellandrene (11.40%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Carum carvi (caraway) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | Limonene (27.60%), carvone (67.50%) | [99] |

| S. aureus | DMSO | ≤1.00 μg/mL | DL-limonene (53.35%), β-selinene (11.08%), β-elemene (10.09%) | [118] | ||

|

| ||||||

| Caryophyllus aromaticus (clove) | ADM90 | S. aureus (ATCC 25923, 16 MRSA and 15 MSSA clinical isolates) | Tween 80 | 2.70 mg/mL | Eugenol (75.85%), eugenol acetate (16.38%) | [119] |

|

| ||||||

| Cinnamomum Cassia (cinnamon) | MIC | S. aureus | DMSO | ≤1.00 μg/mL | trans-Caryophyllene (17.18%), eugenol (14.67%), | [118] |

| Linalool L (14.52%), trans-cinnamyl acetate (13.85%), cymol (11.79%), cinnamaldehyde (11.25%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Cinnamomum zeylanicum (cinnamon) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | Eugenol (80.00%) | [99] |

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | n.m. | 0.02 mg/mL | NCR | [85] | |

| ADM | 10% DMSO | 3.20 mg/mL | [80] | |||

| ADM90 | S. aureus (ATCC 25923, 16 MRSA and 15 MSSA clinical isolates) | Tween 80 | 0.25 mg/mL | Cinnamaldehyde (86.31%) | [119] | |

|

| ||||||

| Citrus aurantifolia (lime) | ADM | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | 10% DMSO | 12.80 mg/mL | Cinnamaldehyde (52.42%) | [80] |

|

| ||||||

| Citrus aurantium (bitter orange), flowers | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | 50% DMSO | 0.31 mg/mL | Limonene (27.50%), E-nerolidol (17.50%), α-terpineol (14.00%) | [120] |

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6536) | 0.63 mg/mL | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Citrus aurantium (petitgrain) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6536) | Acetone | 4.00 mg/mL | Linalyl acetate (54.90%), linalool (21.10%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Citrus bergamia (bergamot) | MAC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | n.m. | 1.25 μL/mL | Bergamol (16.10%), linalool (14.02%), D-limonene (13.76%) | [62] |

|

| ||||||

| Citrus grandis (grapefruit) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 3.00 mg/mL | Limonene (74.80%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Citrus medica limonum (lemon) | ADM | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | 10% DMSO | >12.80 mg/mL | NCR | [80] |

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 3.00 mg/mL | [99] | ||

|

| ||||||

| Citrus sinensis (orange) | ADM | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | 10% DMSO | >12.80 mg/mL | NCR | [80] |

| MAC | S. aureus (ATCC 9144) | 0.1% ethanol | 0.94 mg/L | [121] | ||

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 4.00 mg/mL | Limonene (93.20%) | [99] | |

|

| ||||||

| Commiphora guidotti (myrrh) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 12600) | Acetone | 1.50 mg/mL | (E)-β-Ocimene (52.60%), α-santalene (11.10%), (E)-bisabolene (16.00%) | [117] |

|

| ||||||

| Commiphora myrrha (myrrh) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 12600) | Acetone | 1.30 mg/mL | Furanogermacrene (15.90%), furanoeudesma-1,3-diene (44.30%) | [117] |

| S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | 2.00 mg/mL | Furanoeudesma-1,3-diene (57.70%), lindestrene (16.30%) | [117] | |||

|

| ||||||

| Coriandrum sativum (coriander), seed | MIC | S. aureus (7 clinical isolates) | 0.5% DMSO with Tween 80 | 0.16 mg/mL | NCR | [122] |

|

| ||||||

| Cupressus arizonica (smooth cypress), branches | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | 10% DMSO | 1.50 μg/mL | α-Pinene (58.60%), δ-3-carene (15.60%) | [123] |

| Cupressus arizonica (smooth cypress),female cones | 2.95 μg/mL | α-Pinene (60.50%), δ-3-carene (15.30%) | ||||

| Cupressus arizonica (smooth cypress), leaves | 0.98 μg/mL | α-Pinene (20.00%), umbellulone (18.40%) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Cupressus sempervirens (cypress) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 12.00 mg/mL | α-Pinene (41.20%), δ-3-carene (23.70%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Cymbopogon giganteus (lemongrass) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 9144) | 0.5% ethanol | 2.10 mg/mL | Limonene (42.00%), trans-p-mentha-1(7),8-dien-2-ol (14.20%), cis-p-mentha-1(7),8-dien-2-ol (12.00%) | [124] |

|

| ||||||

| Cymbopogon citratus (lemongrass) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 9144) | 0.5% ethanol | 2.50 mg/mL | Geranial (48.10%), neral (34.60%), myrcene (11.00%) | [124] |

| S. aureus | DMSO | ≤1.00 μg/mL | Geranial (47.34%), β-myrcene (16.53%), Z-citral (8.36%) | [118] | ||

| MAC | S. aureus (MTCC 96) | Sodium taurocholate | 0.80–0.27 μL/mL | Citral (72.80%) | [125, 126] | |

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 1.67 mg/mL | Geranial (44.80%) | [99] | |

|

| ||||||

| Cymbopogon martinii (palmarosa) | MAC | S. aureus (MTCC 96) | Sodium taurocholate | 0.80 μL/mL | Geraniol (61.6%) | [125, 126] |

|

| ||||||

| Cymbopogon nardus (citronella) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 4.00 mg/mL | Citronellal (38.30%), geraniol (20.70%), citronellol (18.80%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Daucus carota (carrot seed) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | Carotol (44.40%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Eucalyptus camaldulensis (eucalyptus) | MAC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | Acetone | 3.90 μg/mL | 1,8-Cineol (54.37%), α-pinene (13.24%) | [127] |

| S. aureus (clinical isolate) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Eucalyptus globulus (eucalyptus) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | Tween 80 | 10.00 mg/mL | 1,8-Cineol (81.93%) | [128] |

| MRSA (ATCC 10442) | ||||||

| MRSA (MRSA USA 300) | ||||||

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 43387) | DMSO | 0.20% v/v | NCR | [129] | |

| MAC | S. aureus (MTCC 96) | Sodium taurocholate | 0.41 μL/mL | Cineole (23.20%) | [125, 126] | |

| ADM | MRSA (ATCC 33592) | Tween 20 | 85.60 μg/mL | Eucalyptol (47.20%), (+)-spathulenol (18.10%) | [81] | |

| S. aureus (ATCC 25922) | 51.36 μg/mL | |||||

| MRSA (14 clinical isolates) | 8.56–85.60 μg/mL | |||||

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 4.00 mg/mL | 1,8-Cineole (58.00%), α-terpineol (13.20%) | [99] | |

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | NCR | [130] | |

| MRSA (ATCC 33592) | 0.75 mg/mL | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Eucalyptus radiata (eucalyptus) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | 1,8-Cineole (65.7% ± 9.5), α-terpineol (12.8% ± 4.4) | [130] |

| MRSA (ATCC 33592) | 1.00–2.00 mg/mL | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Eucalyptus camaldulensis (eucalyptus) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | Acetone | 0.50 mg/mL | NCR | [130] |

| MRSA (ATCC 33592) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Eucalyptus citriodora (eucalyptus) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | Acetone | 1.00 mg/mL | NCR | [130] |

| MRSA (ATCC 33592) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Eucalyptus smithii (eucalyptus) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | NCR | [130] |

| MRSA (ATCC 33592) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Eucalyptus dives (eucalyptus) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | NCR | [130] |

| MRSA (ATCC 33592) | 1.00 mg/mL | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Eucalyptus intertexta (eucalyptus) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 29737) | 10% DSMO | 7.80 μg/mL | NCR | [131] |

|

| ||||||

| Eucalyptus largiflorens (eucalyptus) | MAC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | n.m. | 7.80 μg/mL | 1,8-Cineol (70.32%), α-pinene (15.46%) | [127] |

| S. aureus (clinical isolate) | ||||||

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 29737) | 10% DSMO | 250.00 μg/mL | NCR | [131] | |

|

| ||||||

| Eucalyptus melliodora (eucalyptus) | MAC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | n.m. | 3.90 μg/mL | 1,8-Cineol (67.65%), α-pinene (18.58%) | [127] |

| S. aureus (clinical isolate) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Eucalyptus polycarpa (eucalyptus) | MAC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | n.m. | 1.95 μg/mL | 1,8-Cineol (50.12%) | [127] |

| S. aureus (clinical isolate) | 3.90 μg/mL | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Foeniculum dulce (fennel) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | E-Anethole (79.10%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Foeniculum vulgare (fennel) | MAC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | DMSO | >10.00 mg/mL | trans-Anethole (68.53%), estragole (10.42%) | [132] |

| Foeniculum vulgare (fennel) (6 samples) | MIC | S. aureus | ≤1.00 μg/mL | trans-Anethole (33.3%), DL-limonene (19.66%), carvone (12.03%) | [118] | |

| S. aureus (ATCC 28213) | 125.00–500.00 μg/mL | Fenchone (16.90–34.70%), estragole (2.50–66.00%), trans-anethole (7.90–77.70%) | [133] | |||

|

| ||||||

| Foeniculum vulgare Mill. ssp. vulgare (fennel), Aurelio | MAC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | Tween 20 | 50.00–100.00 μg/mL | Limonene (16.50–21.50%), (E)-anethole (59.80–66.00%) | [134] |

| Foeniculum vulgare Mill. ssp. vulgare (fennel), Spartaco | Limonene (0.20–17.70%), (E)-anethole (66.30–90.40%) | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Geranium dissectum (geranium) | MIC | S. aureus | DMSO | ≤1.00 μg/mL | β-Citronellol (25.45%), geraniol (13.83%) | [118] |

|

| ||||||

| Hyssopus officinalis (hyssop) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 3.00 mg/mL | Isopinocamphone (48.70%), pinocamphone (15.50%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Juniperi aetheroleum (juniper) | MAC80 | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | n.m. | 40.00% v/v | α-Pinene (29.17%), β-pinene (17.84%), sabinene (13.55%) | [135] |

| MAC80 | S. aureus (MFBF) | 15.00% v/v | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Juniperus communis (juniper), berry | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | n.m. | 10.00 mg/mL | NCR | [85] |

| MIC | MRSA (15 clinical isolates) | Ethanol | >2.00% v/v | [136] | ||

|

| ||||||

| Juniperus excelsa (juniper), berries, Dojran | ADM | S. aureus (ATCC 29213) | 50% DSMO | >50.00% | α-Pinene (70.81%) | [87] |

| Juniperus excelsa (juniper), leaves, Dojran | 125.00% | α-Pinene (33.83%) | ||||

| Juniperus excelsa (juniper), leaves, Ohrid | 125.00% | Sabinene (29.49%) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Juniperus officinalis (juniper), berry | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 29213) | Tween 80 | 10.00 mg/mL | α-Pinene (39.76%) | [128] |

| Juniperus officinalis (juniper), berry | MRSA (clinical isolates) | 20.00 mg/mL | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Juniperus virginiana (juniper) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | Thujopsene (29.80%), cedrol (14.90%), α-cedrene (12.40%) | [99] |

| Juniperus virginiana (juniper), berries | 3.00 mg/mL | α-Pinene (20.50%), myrcene (13.70%), bicyclosesquiphellandrene (10.70%) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Kunzea ericoides (Kānuka) | MAC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Tween 80 | 0.25% v/v | α-Pinene (61.60%) | [137] |

| MRSA (clinical isolate) | 0.20% v/v | |||||

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 12600) | Acetone | 8.00 mg/mL | α-Pinene (26.2–46.7%), p-cymene (5.8–19.1%) | [138] | |

|

| ||||||

| Laurus nobilis (bay) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 0.83 mg/mL | Eugenol (57.20%), myrcene (14.30%), carvacrol (12.70%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Lavandula angustifolia (lavender) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | Linalyl acetate (36.70%), linalool (31.40%), terpinen-4-ol (14.90%) | [99] |

| S. aureus (NCTC 6571) | 10% DSMO | 310.00 μg/mL | Linalool (25.10%), linalyl acetate (22.50%) | [139] | ||

| S. aureus (NCTC 1803) | 320.40 μg/mL | |||||

| MRSA (15 clinical isolates) | Ethanol | 0.50% v/v | NCR | [136] | ||

| S. aureus (ATCC 12600) | Acetone | 8.60 mg/mL | Linalool (30.80%), linalyl acetate (31.30%) | [140] | ||

| S. aureus (clinical strain and ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | Linalyl acetate (36.7%), linalool (31.4%), terpinen-4-ol (14.9%) | [99] | ||

| MRSA (clinical strain and 43300) | ||||||

| Methicillin-gentamicin-resistant S. aureus (MGRSA) (ATCC 33592) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Lavandula dentata (French lavender) | MIC | S. aureus (BNI 18) | 5% DMSO | 1.53 mg/mL | Camphor (12.40%) | [141] |

| Lavandula officinalis (lavender) | MIC | S. aureus | DMSO | ≤1.00 μg/mL | δ-3-Carene (17.14%), α-fenchene (16.79%), diethyl phthalate (13.84%) | [118] |

| Lavandula stoechas (French lavender) | MIC | S. aureus (STCC 976) | Tween 80 | 2.00 μL/mL | 10s,11s-Himachala-3(12),4-diene (23.62%), cubenol (16.19%) | [142] |

|

| ||||||

| Lavandula stoechas (French lavender), flower | MIC | MRSA (clinical isolate) | 20% DMSO | 31.25 μg/mL | α-Fenchone (39.20%) | [47] |

| Lavandula stoechas (French lavender), leaf | 125.00 μg/mL | α-Fenchone (41.90%), 1,8-cineole (15.60%), camphor (12.10%) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Leptospermum scoparium (manuka) | MAC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Tween 80 | 0.10% v/v | (−)-(E)-Calamenene (14.50%), leptospermone (17.60%) | [137] |

| MRSA (clinical isolate) | 0.05% v/v | |||||

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 12600) | Acetone | 4.00 mg/mL | Eudesma-4(14),11-diene (6.2–14.5%), α-selinene (5.90–13.5%), (E)-methyl cinnamate (9.2–19.5%) | [138] | |

|

| ||||||

| Litsea cubeba (May Chang) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 1.50 mg/mL | Geranial (45.60%), nerol (31.20%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Matricaria chamomilla (German chamomile) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 1.50 mg/mL | Bisabolene oxide A (46.90%), β-farnesene (19.20%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Matricaria recutita (German chamomile) | ADM90 | S. aureus (ATCC 25923, 16 MRSA and 15 MSSA clinical isolates) | Tween 80 | 26.50 mg/mL | Chamazulene (31.48%), α-bisabolol (15.71%), bisabolol oxide (15.71%) | [119] |

|

| ||||||

| Matricaria songarica (chamomile) | MIC | S. aureus (CCTCC AB91093) | Tween 80 | 50.00 μg/mL | E-β-Farnesene (10.58%), bisabolol oxide A (10.46%) | [143] |

|

| ||||||

| Melaleuca alternifolia (tea tree) | ADM | S. aureus (NCIM 2079) | Tween 80 | 1.00% | NCR | [79] |

| S. aureus (clinical isolate) | ||||||

| MAC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Tween 80 | 0.25% v/v | α-Terpinene (11.40%), γ-terpinene (22.50%), terpinen-4-ol (35.20%) | [137] | |

| MRSA (clinical isolate) | 0.35% v/v | |||||

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 29213) | None used | 0.50% (v/v) | Terpinen-4-ol (40.00%), δ-terpinen (13.00%), p-cymene (13.00%) | [97] | |

| MRSA (98 clinical isolates) | n.m. | 512.00–2048.00 mg/L | NCR | [144] | ||

| S. aureus (NCIB 6571) | 1.00% v/v | [145] | ||||

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci (9 clinical isolates) | Polyoxyl 35 castor oil | 0.63–2.50% v/v | Terpinen-4-ol (>35.00%) | [146] | ||

| MRSA (10 clinical isolates) | 0.30–0.63% v/v | |||||

| 0.30% v/v | ||||||

| MRSA (15 clinical isolates) | Ethanol | 0.25% v/v | NCR | [136] | ||

| S. aureus (ATCC 12600) | Acetone | 8.60 mg/mL | Terpinen-4-ol (38.60%), γ-terpinene (21.60%) | [140] | ||

| MIC90 | S. aureus (NCTC 6571) | Tween 80 | 0.25% v/v | Terpinen-4-ol (35.70%) | [147] | |

| S. aureus (105 clinical isolates) | 0.12–0.50% v/v | |||||

| MIC | MRSA (60 clinical isolates, 29 mupirocin-resistant) | 0.25% | [148] | |||

| MIC | S. aureus (NCTC 8325) | n.m. | 0.50% (v/v) | Terpinen-4-ol (39.80%), γ-terpinene (17.80%) | [149] | |

| 0.25% (v/v) | [150] | |||||

| MIC90 | MRSA (100 clinical isolates) | Tween 80 | 0.16–0.32% | NCR | [151] | |

| MIC | S. aureus (69 clinical isolates) | Tween 80 | 0.12–0.50% v/v | Terpinen-4-ol (35.70%) | [152] | |

| ADM | S. aureus (NCTC 4163) | Tween 20 | 0.20% v/v | Terpinen-4-ol (42.80%), γ-terpinene (18.20%) | [115] | |

| MRSA (clinical isolate) | 0.30% v/v | |||||

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 8.00 mg/mL | Terpinen-4-ol (49.30%), γ-terpinene (16.90%) | [99] | |

| MAC | S. aureus (2 clinical isolates) | n.m. | 0.10–0.20% | Eucalyptol (70.08%) | [153] | |

| S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | 0.20% | |||||

| S. aureus (NCTC 9518) | 0.63–1.25% v/v | α-Pinene (11.95%), α-terpinene (14.63%), terpinen-4-ol (29.50%), p-cymene (17.74%) | [154] | |||

| α-Pinene (24.87%), α-terpinene (12.47%), terpinen-4-ol (28.59%) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Melaleuca cajuputi (cajuput) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | Tween 80 | 2.50 mg/mL | 1,8-Cineol (67.60%) | [128] |

| MRSA (ATCC 10442) | 5.00 mg/mL | |||||

| MRSA (clinical isolate) | 2.50 mg/mL | |||||

| MAC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | 0.20% v/v | 1,8-Cineole (55.50%) | [137] | ||

| MRSA (clinical isolate) | 0.30% v/v | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Melaleuca quinquenervia (niaouli) | MAC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Tween 80 | 0.20% v/v | 1,8-Cineole (61.20%) | [137] |

| MRSA (clinical isolate) | 0.30% v/v | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Melaleuca viridiflora (niaouli) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | 1,8-Cineole (45.90%), α-terpinene (21.00%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Melissa officinalis (lemon balm) | MIC | S. aureus (NCTC 6571) | 10% DSMO | 300.60 μg/mL | 1,8-Cineol (27.40%), α-thujone (16.30%), β-thujone (11.20%), borneol (10.40%) | [139] |

| MIC | S. aureus (NCTC 1803) | 330.30 μg/mL | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Mentha piperita (peppermint) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 12600) | Acetone | 11.90 mg/mL | Menthone (18.20%), menthol (42.90%) | [140] |

| S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | Tween 80 | 0.60 mg/mL | 1,8-Cineol (12.06%), menthone (22.24%), menthol (47.29%) | [128] | ||

| MRSA (ATCC 10442) | ||||||

| MRSA (clinical isolate) | ||||||

| S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | DMSO | 0.63–2.50 mg/mL | Menthol (27.50–42.30%), menthone (18.40–27.90%) | [155] | ||

| S. aureus | ≤1.00 μg/mL | Menthone (40.82%), carvone (24.16%) | [118] | |||

| MRSA (15 clinical isolates) | Ethanol | 0.50% v/v | NCR | [136] | ||

| S. aureus (ATCC 43387) | DMSO | 0.20% v/v | [129] | |||

| MAC | S. aureus (MTCC 96) | Sodium taurocholate | 1.66 μL/mL | Menthol (36.40%) | [125, 126] | |

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 9144) | 0.5% ethanol | 8.30 mg/mL | Menthol (39.30%), menthone (25.20%) | [156] | |

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 4.00 mg/mL | Menthol (47.50%), menthone (18.60%) | [99] | |

|

| ||||||

| Myrtus communis (myrtle) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | Myrtenyl acetate (28.20%), 1,8-cineole (25.60%), α-pinene (12.50%) | [99] |

| ADM | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Tween 20 | 2.80 mg/mL | NCR | [157] | |

| S. aureus (ATCC 29213) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Ocimum basilicum (basil) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 9144) | 0.5% ethanol | 2.50 mg/mL | Linalool (57.00%), eugenol (19.20%) | [156] |

| MAC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | n.m. | 1.25 μL/mL | Eugenol (62.60%), caryophyllene (21.51%) | [62] | |

| Tween 80 | 0.07 × 10−2% v/v | Linalool (54.95%), methyl chavicol (11.98%) | [158] | |||

| S. aureus (3 clinical strains) | Tween 80 | ((0.15–0.30) × 10)−2 % v/v | Linalool (54.95%), methyl chavicol (11.98%) | [158] | ||

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 1.50 mg/mL | Linalool (54.10%) | [99] | |

| MIC90 | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | n.m. | 45.00 μg/mL | Methyl chavicol (46.90%), geranial (19.10%), neral (15.15%) | [159] | |

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Tween 80 | 0.68–11.74 μg/mL | Linalool (30.30–58.60%) | [160] | |

|

| ||||||

| Origanum acutidens (Turkey oregano) | MIC | S. aureus (clinical isolate) | 10% DMSO | 125.00 μg/mL | Carvacrol (72.00%) | [161] |

| S. aureus (ATCC2913) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Origanum majorana (marjoram) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 43387) | DMSO | 0.05% v/v | NCR | [129] |

| S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | 1,8-Cineole (46.00%), linalool (26.10%) | [99] | ||

|

| ||||||

| Origanum microphyllum (oregano) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | Tween 80 | 6.21 mg/mL | Terpin-4-ol (24.86%), γ-terpinene (13.83%), linalool (10.81%) | [162] |

|

| ||||||

| Origanum scabrum (oregano) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | Tween 80 | 0.35 mg/mL | carvacrol (74.86%) | [162] |

|

| ||||||

| Origanum vulgare (oregano) | ADM | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | 1% DMSO | 0.13% v/v | p-Cymene (14.60%), γ-terpinene (11.70%), thymol (24.70%), carvacrol (14.00%) | [163] |

| S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | ||||||

| S. aureus (ATCC 43300) | ||||||

| MRSA (22 isolates) | 0.06–0.13% v/v | |||||

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | n.m. | 575.00 mg/L | NCR | [164] | |

| MAC | 0.63.00 μL/mL | Carvacrol (30.17%), p-cymene (15.20%), γ-terpinen (12.44%) | [62] | |||

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 43387) | DMSO | 0.10% v/v | NCR | [129] | |

| ADM | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Tween 20 | 0.70 mg/mL | [157] | ||

| S. aureus (ATCC 29213) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Origanum vulgare subsp. hirtum (Greek oregano) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | 10% DMSO + Tween 80 | 170.70 μg/mL | Linalool (96.31%) | [165] |

| Origanum vulgare subsp. vulgare (oregano) | 106.70 μg/mL | Thymol (58.31%), carvacrol (16.11%), p-cymene (13.45%) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Pelargonium graveolens (geranium) | ADM | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | 10% DMSO | >12.80 mg/mL | NCR | [80] |

| S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Tween 20 | 0.72 mg/mL | [157] | |||

| S. aureus (ATCC 29213) | ||||||

| MIC | S. aureus (strains isolated from skin lesions) | Ethanol | 0.25–1.50 mL/mL | Citronellol (26.70%), geraniol (13.40%) | [166] | |

| S. aureus (strains isolated postoperatively) | 0.50–2.25 mL/mL | |||||

| MRSA and MSSA (clinical strains) | 1.00 mL/mL | |||||

| S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 1.50 mg/mL | Citronellol (34.20%), geraniol (15.70%) | [99] | ||

|

| ||||||

| Perovskia abrotanoides (Russian sage) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | 10% DMSO | 8.00 μL/mL | Camphor (23.00%), 1,8-cineole (22.00%), α-pinene (12.00%) | [167] |

|

| ||||||

| Pimpinella anisum (anise) | MIC | S. aureus | DMSO | 125.00 μg/mL | NCR | [168] |

| ≤1.00 μg/mL | Anethole (64.82%) | [118] | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Pinus sylvestris (pine) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 4.00 mg/mL | Bornyl acetate (42.30%), camphene (11.80%), α-pinene (11.00%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Piper nigrum (black pepper) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | β-Caryophyllene (33.80%), limonene (16.40%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Pogostemon cablin (patchouli) | MIC | S. aureus (NCTC 6571) | 10% DSMO | 395.20 μg/mL | α-Guaiene (13.80%), α-bulnesene (17.10%), patchouli alcohol (22.70%) | [139] |

| S. aureus (NCTC 1803) | 520.00 μg/mL | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Pogostemon patchouli (patchouli) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 1.50 mg/mL | Patchouli alcohol (37.30%), α-bulnesene (14.60%), α-guaiene (12.50%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Rosmarinus officinalis (rosemary) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Tween 80 | 0.13% v/v | 1,8-Cineole (27.23%), α-pinene (19.43%), camphor (14.26%), camphene (11.52%) | [169] |

| S. aureus (NCTC 6571) | 10% DSMO | 305.30 μg/mL | 1,8-Cineol (29.2%), (+)-camphor (17.2%) | [139] | ||

| S. aureus (NCTC 1803) | 310.40 μg/mL | |||||

| MRSA (clinical isolate) | Tween 80 | 0.03% v/v | 1,8-Cineole (26.54%), α-pinene (20.14%), camphene (11.38%), camphor (12.88%) | [170] | ||

| S. aureus (MTCC 96) | n.m. | >11.00 mg/mL | NCR | [171] | ||

| S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Hexane | 1.88–7.50 mg/mL | 1,8-Cineole (10.56–11.91%), camphor (16.57–16.89%), verbenone (17.43–23.79%) | [172] | ||

| ADM | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | 10% DMSO | >12.80 mg/mL | NCR | [80] | |

| S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Tween 20 | 5.60 mg/mL | [157] | |||

| S. aureus (ATCC 29213) | ||||||

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 12600) | Acetone | 6.20 mg/mL | 1,8-Cineole (41.40%), α-pinene (13.30%), camphor (12.40%) | [140] | |

| S. aureus (ATCC 43387) | DMSO | 0.20% v/v | NCR | [129] | ||

| S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 4.00 mg/mL | 1,8-Cineole (48.00%) | [99] | ||

| ADM90 | S. aureus (ATCC 25923, 16 MRSA and 15 MSSA clinical isolates) | Tween 80 | 8.60 mg/mL | Camphor (27.51%), limonene (21.01%), myrcene (11.19%), α-pinene (10.37%) | [119] | |

|

| ||||||

| Salvia bracteata (sage) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | 50.00 μg/mL | Caryophyllene oxide (16.60%) | [173] | |

| Salvia eremophila (sage) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 29737) | 10% DMSO | 8.00 μg/mL | Borneol (21.83%), α-pinene (18.80%), bornyl acetate (18.68%) | [174] |

| Salvia nilotica (sage) | ADM | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | n.m. | 5.40 mg/mL | trans-Caryophyllene (10.90%) | [175] |

|

| ||||||

| Salvia officinalis (sage) | MIC | S. aureus (NCTC 6571) | 10% DSMO | 302.40 μg/mL | 1,8-Cineol (27.40%), α-thujone (16.30%), β-thujone (11.20%), borneol (10.40%) | [139] |

| S. aureus (NCTC 1803) | 324.30 μg/mL | |||||

| S. aureus (ATCC 43387) | DMSO | 0.20% v/v | NCR | [129] | ||

| ADM | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Tween 20 | 11.20 mg/mL | NCR | [157] | |

| S. aureus (ATCC 29213) | 5.60 mg/mL | |||||

| S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | n.m. | 7.50 mg/mL | [176] | |||

|

| ||||||

| Salvia ringens (sage) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | n.m. | NI | α-Pinene (12.85%), 1,8-cineole (46.42%) | [177] |

| Salvia rosifolia (sage) (3 samples) | MRSA | 20% DMSO | 125.00–1000.00 μg/mL | α-Pinene (15.70–34.80%), 1,8-cineole (16.60–25.10%), β-pinene (6.70–13.50%) | [178] | |

| Salvia rubifolia (sage) | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | Tween 20 | 50.00 μg/mL | γ-Muurolene (11.80%) | [173] | |

|

| ||||||

| Salvia sclarea (clary sage) | MIC | S. aureus (11 MRSA and 16 MSSA) | Ethanol | 3.75–5.25 | Linalyl acetate (57.90%), linalool (12.40%) | [179] |

| S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | Linalyl acetate (72.90%), linalool (11.90%) | [99] | ||

|

| ||||||

| Santalum album (sandalwood) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 0.25 mg/mL | α-Santalol (32.10%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Styrax benzoin (benzoin) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 2.00 mg/mL | cinnamyl alcohol (44.80%), benzene propanol (21.70%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Syzygium aromaticum (clove) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Tween 80 | 0.13% v/v | Eugenol (68.52%), β-caryophyllene (19.00%), 2-methoxy-4-[2-propenyl]phenol acetate (10.15%) | [169] |

| S. aureus | DMSO | ≤1.00 μg/mL | Eugenol (84.07%), isoeugenol (10.39%) | [118] | ||

| ADM | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | 10% DMSO | >6.40 mg/mL | NCR | [80] | |

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 1.50 mg/mL | Eugenol (82.20%), eugenol acetate (13.20%) | [99] | |

|

| ||||||

| Tagetes minuta (Mexican marigold) | MIC90 | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | n.m. | 67.00 μg/mL | Dihydrotagetone (33.90%), E-ocimene (19.90%), tagetone (16.10%) | [159] |

| Tagetes patula (French marigold) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 4.00 mg/mL | (E)-β-Ocimene (41.30%), E-tagetone (11.20%), verbenone (10.90%) | [99] |

|

| ||||||

| Thymbra spicata (thyme) | MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 29213) | Tween 80 | 2.25 mg/mL | Carvacrol (60.39%), γ-terpinene (12.95%) | [180] |

| Thymus capitatus (thyme) | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | 900.00 μg/mL | p-Cymene (26.40%), thymol (29.30%), carvacrol (10.80%) | [181] | ||

| Thymus capitatus (thyme), commercial | α-Pinene (25.20%), linalool (10.30%), thymol (46.10%) | |||||

| Thymus herba-barona (thyme), Gennargentu | 225.00 μg/mL | Thymol (46.90%), carvacrol (20.60%) | ||||

| Thymus herba-barona (thyme), Limbara | 900.00 μg/mL | p-Cymene (27.60%), thymol (50.30%) | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Thymus hyemalis (thyme) (thymol, thymol/linalool, carvacrol chemotypes) | MAC | S. aureus (CECT 239) | 95% ethanol | <0.20–0.50 μL/mL | p-Cymene (16.00–19.80%), linalool (2.10–16.60%), thymol (2.90–43.00%), carvacrol (0.30–40.10%) | [61] |

|

| ||||||

| Thymus numidicus | ADM | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | n.m. | 0.23 mg/mL | NCR | [176] |

| Thymus serpyllum (thyme) | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Tween 20 | 0.28 mg/mL | [157] | ||

| S. aureus (ATCC 29213) | 0.70 mg/mL | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Thymus vulgaris (thyme) | MIC | S. aureus | DMSO | 31.20 μg/mL | NCR | [168] |

| S. aureus (NCTC 6571) | 10% DSMO | 160.50 μg/mL | p-Cymene (17.90%), thymol (52.40%) | [139] | ||

| S. aureus (NCTC 1803) | 210.00 μg/mL | |||||

| S. aureus (ATCC 25923) | n.m. | 0.40 mg/mL | NCR | [85] | ||

| ADM | S. aureus (ATCC 433000) | Ethanol | 0.25 μL/mL | Thymol (38.1%), p-cymene (29.10%) | [182] | |

| S. aureus (2 multidrug-resistant clinical strains from hands) | 0.50 μL/mL | Thymol (38.1%), p-cymene (29.10%) | [182] | |||

| S. aureus (6 multidrug-resistant clinical strains from wounds) | 0.50–1.00 μL/mL | |||||

| S. aureus (4 multidrug-resistant clinical strains from ulcers) | 0.50–0.75 μL/mL | |||||

| S. aureus (multidrug-resistant clinical strain from abscesses) | 0.25 μL/mL | |||||

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 12600) | Acetone | 1.30 mg/mL | Thymol (47.20%), p-cymene (22.10%) | [140] | |

| MRSA (15 clinical isolates) | Ethanol | 0.50% v/v | NCR | [136] | ||

| ADM | MRSA (ATCC 33592) | Tween 20 | 18.50 μg/mL | Thymol (48.1%), p-cymene (15.60%), γ-terpinene (15.40%) | [81] | |

| S. aureus (ATCC 25922) | ||||||

| MRSA (14 clinical isolates) | 18.50–37.00 μg/mL | |||||

| MIC | S. aureus (ATCC 6538) | Acetone | 3.33 mg/mL | p-Cymene (39.90%), thymol (20.70%) | [99] | |

|

| ||||||