Abstract

Spiroketals are structural motifs found in many biologically active natural products, which has stimulated considerable efforts toward their synthesis and interest in their use as drug lead compounds. Despite this, the use of spiroketals, and especially bisbenzanulated spiroketals, in a structure‐based drug discovery setting has not been convincingly demonstrated. Herein, we report the rational design of a bisbenzannulated spiroketal that potently binds to the retinoid X receptor (RXR) thereby inducing partial co‐activator recruitment. We solved the crystal structure of the spiroketal–hRXRα–TIF2 ternary complex, and identified a canonical allosteric mechanism as a possible explanation for the partial agonist behavior of our spiroketal. Our co‐crystal structure, the first of a designed spiroketal–protein complex, suggests that spiroketals can be designed to selectively target other nuclear receptor subtypes.

Keywords: drug design, drug discovery, natural products, spiro compounds, structure elucidation

Spiroketals are archetypal spirocyclic compounds,1 found abundantly in the CAS registry (Supporting Information), of which many are bioactive natural products.2, 3 Besides being attractive targets for total synthesis,4, 5, 6 spiroketal‐derived natural products have contributed to a renaissance of thinking towards intelligent library design, grounded in principles of diversity‐oriented synthesis (DOS)7 and biology‐oriented synthesis (BIOS).8, 9 Spiroketals are arguably well‐adapted to both philosophical approaches in being biologically relevant2, 3 while fulfilling the three criteria for molecular diversity set out by Schreiber and co‐workers—appendage, stereochemistry, skeletal diversity7—owing in particular to the conformational and configurational flexibility of these scaffold structures. A BIOS study on spiroketals performed by Waldmann and co‐workers10, 11, 12 clearly placed these structures within a hierarchical classification of bioactive scaffold structures, navigable with the help of cheminformatics tools such as Scaffold Hunter,15 and inspired the design of other spiroketal libraries for phenotypic screening.13, 14

Recently, 3D‐pharmacophore modelling was used to design spiroketal‐derived sugars, which showed inhibitory activity towards SGLT2.19 To the best of our knowledge, the co‐crystal structure of bistramide A bound to actin,20 and the bis‐spiroketals pinnatoxins A and G21 are to date the only examples of spiroketals bound to protein targets. Benzannulated spiroketals are a relevant subtype of spiroketals,3 which includes the antibiotic rubromycin family (Figure 1 A).22 Recent reports have revealed that these molecules function as telomerase inhibitors, with the [6,5]‐spiroketal ring system in this case playing an essential role in the rubromycin's pharmacophore.22 Despite the abundance of spiroketals and their highlighted potential as medicinal chemistry scaffolds, the structure‐based design and structural validation of spiroketals as medicinal chemistry scaffolds has not been clearly demonstrated.

Figure 1.

Design of a spiroketal as RXR ligand. a) Molecular structures of γ‐rubromycin, [6,6]‐bisbenzannulated spiroketal 1 and RXR full agonists, BMS 649 16 and LG100268. b) Top‐ranked pose of R‐1 generated by docking into the space occupied by BMS 649 in the hRXRα‐BMS 649 co‐crystal structure (PDB code: 1MVC)16 using the FlexX docking module in the LeadIT suite17 followed by HYDE scoring in SEESAR.18 R‐1 skeleton: C=pink, O=red; protein backbone: C=green, N=blue, O=red, S=yellow; dashed lines=H‐bonding interactions below 3.3 Å.

A reported crystal structure of a [6,6]‐bisbenzannulated spiroketal23 inspired us to consider these structures as nuclear receptor (NR) ligands, which we speculated would possess the correct size, shape, and hydrophobicity to target the L‐shaped ligand binding pocket (LBP) of the retinoid X receptor (RXR),24 a member of the superfamily of gene transcription factors. RXR plays a central role in hormone‐driven cell‐signaling events through its ability to heterodimerize with other type II nuclear receptors.25 RXR is a drug target for the treatment of cutaneous T‐cell lymphoma and is under investigation as a potential treatment for Alzheimer's Disease.26 Despite the fact that RXR ligands have been thoroughly investigated,27 only a very few RXR partial agonists with limited structural diversity have been characterized, and rules guiding the design of heterodimer‐specific RXR ligands are essentially non‐existent. In part as a response to these challenges, and in continuation of our group's recent efforts to identify selective RXR28 and other NR modulators,29 we report the first designed spiroketal protein modulator, as exemplified by RXR modulation.

To assess the potential of bisbenzannulated spiroketals to target RXR, we adopt a classical scaffold‐hopping approach30 commencing with the co‐crystal structure of commercial nanomolar‐potent RXR full agonist BMS 649 (otherwise known as SR11 237)31 bound to hRXRα (PDB code: 1MVC).16 We then replaced the rigid acetal linker present in BMS 649 with a [6‐6]‐bisbenzannulated spiroketal linker while retaining the key tetramethyl‐tetrahydronaphthyl‐ and carboxylic acid groups,32 to generate 1. We then modelled and docked both enantiomers of 1 into the space occupied by BMS 649 in the LBD of the hRXRα‐BMS 649 co‐crystal structure16 using the FlexX docking module in the LeadIT suite followed by evaluation using the scoring function HYDE in SEESAR (Figure 1). While all attempts at docking the S‐enantiomer in this PDB structure failed to generate poses, we succeeded in docking the R‐enantiomer, with the best pose shown in Figure 1 B. Although our docking studies did not take into account the thermodynamic preferences of the spiroketal ring system, interestingly, R‐1 adopts a diaxial ring conformation, which would be favored owing to bis‐anomeric stabilization. In this ring conformation favorable polar interactions are maintained between the carboxylic acid of R‐1, Arg316, and the backbone of Ala327.

To enable an expedient testing of our binding hypothesis, we elected for a racemic synthesis of (±)‐1, with a view to separating the enantiomeric spiroketals by chiral HPLC at a later stage. In reported syntheses of [6,5]‐33, 34 and [6,6]‐bisbenzannulated spiroketals,3 the spiroketal core is frequently formed under thermodynamically driven conditions through a dehydrative ring cyclisation. Our synthesis of (±)‐1 was based on work by Brimble and co‐workers on analogous [6,6]‐bisbenzannulated spiroketals23 and is described in Scheme 1. We reacted aldehyde 3 with the lithium acetylide of 2 to obtain alkynol 4 in a reasonable 58 % yield. After subsequent catalytic hydrogenation of 4, we performed a Dess–Martin oxidation on the resulting secondary alcohol 5 to generate the spirocyclization precursor, 6, which we treated with trimethylsilyl bromide to effect a one‐pot deprotection/cyclization, which produced the [6,6]‐bisbenzannulated spiroketal 7 in a yield of 64 %. The synthesis of (±)‐1 concluded with a straightforward base‐mediated hydrolysis of the methyl ester group. The resonance peak at δc 97.0 ppm in the 13C‐NMR spectra of 7 and (±)‐1 is diagnostic for the spirocarbon, while the 1H resonances corresponding to the two sets of diastereotopic protons H3, H3′, H4 and H4′ suggest that the spiroketal adopts a diaxial ring conformation (Supporting Information) similar to analogous structures.23

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: a) n‐BuLi, THF, −78 °C to RT; b) 10 % Pd/C, KHCO3, EtOAc, RT; c) Dess–Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2, RT; d) TMSBr, CH2Cl2, −30 °C to RT; e) NaOH, dioxane/MeOH, 40 °C. Characteristic 1H and 13C resonance peaks are summarized for 7 and (±)‐1.23

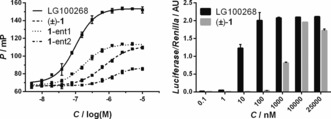

We profiled the RXRα‐activity of (±)‐1 alongside full agonist LG100268 (Figure 1 A)36 in a fluorescence‐based cofactor recruitment assay (Figure 2, left and Table 1). As expected,28 LG100268 induced potent recruitment of the D22 peptide37 with an EC50=0.10±0.01 μm. Intriguingly, (±)‐1 was also active, with an EC50=0.73±0.06 μm, and additionally exhibited a partial agonist behavior, as judged by the levelling off of polarization at 53 % of the maximum response induced by LG100268. We tested (±)‐1 against two other LXXLL‐derived peptides (Table 1), ribosome display peptide Pro2235 and the naturally occurring peptide TIF2,38 and observed similar EC50 values but different % efficacies. One of the separated enantiomers, 1‐ent1, was found to approach the potency of LG100268 in the same FP assay (Figure 2, left and Table 1). Furthermore, 1‐ent1 displayed seven‐fold higher potency and two‐fold higher % efficacy than the other enantiomer, 1‐ent2. The isolated enantiomers did not evidently epimerize under the acidic separation conditions (Supporting Information) nor was any significant change in EC50 value observed for either 1‐ent1 or 1‐ent2 in the same FP assay over a 24 h period (Supporting Information) as evidence of the stability of these compounds under the aqueous assay conditions. Our findings are consistent with those from studies on similar benzannulated spiroketals39 and the fact that analogous natural products are isolated as single enantiomers.40

Figure 2.

Biochemical and cellular evaluation of (±)‐1. Left: Fluorescence polarization assay data showing that full agonist LG100268 induces binding of the fluorescently labelled D22 peptide in a concentration‐dependent manner, while (±)‐1, 1‐ent1, and 1‐ent2 (separable by chiral HPLC) each exhibit a partial agonist behavior. Right: Cellular activities of LG100268 and (±)‐1 measured in a mammalian two‐hybrid luciferase assay. Error bars denote s.d. (n=3).

Table 1.

Summary of FP and cellular M2H data.

| Compound | Fluorescence Polarization | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide[a] | EC50 (±) [μm] | %eff | |

| LG100268 | D22[b] | 0.10 (0.01) | 100 |

| TIF2[c] | 0.48 (0.02) | 100 | |

| Pro22[c] | 0.25 (0.01) | 100 | |

| (±)‐1 | D22[b] | 0.73 (0.06) | 53 |

| TIF2[c] | 0.47 (0.06) | 28 | |

| Pro22[c] | 0.43 (0.01) | 59 | |

| 1‐ent1 | D22[b] | 0.17 (0.02) | 54 |

| 1‐ent2 | D22[b] | 1.20 (0.33) | 26 |

To evaluate 1 under more biologically relevant conditions, we compared (±)‐1 and LG100268 in a mammalian two‐hybrid (M2H) luciferase assay (Figure 2, right). As expected,28 LG100268 produced a full and potent concentration‐dependent response (Figure 2, right). (±)‐1 was also active under the assay conditions, though less potent than LG100268, and the partial response less emphatic than that observed in the FP assay. The difference in % efficacy observed for (±)‐1 in both the in vitro FP and cellular M2H assays might be explained by differences in protein concentration between the two assay formats. Nevertheless, we could conclude that (±)‐1 is cell permeable and active toward gene transcription similarly to an established RXR full agonist.

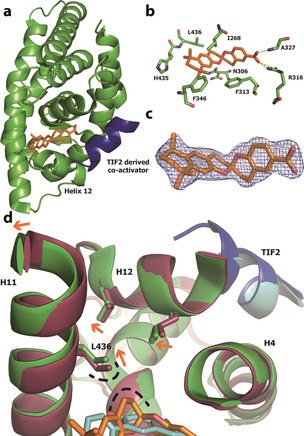

To provide a structural explanation for the observed RXR activity, we co‐crystallized (±)‐1 with the hRXRα LBD‐TIF2 peptide complex and solved the structure to a resolution of 2.17 Å (Figure 3). Globally, the protein adopts a canonical,41 agonistic, folded state with the helix co‐activator bound to the AF2 (Figure 3 A). Closer inspection of the RXR LBP revealed clear electron density indicative of a single spiroketal molecule. On closer inspection, the R‐enantiomer, with the spiroketal ring system in a bis‐anomeric diaxial conformation, fitted best in the electron density (Figure 3 C and Supporting Information). The carboxylate group of R‐1 engages in a canonical polar interaction with the side chain of Arg316 and hydrogen bonds with the protein backbone at residue Ala327 (Figure 3 B). Interestingly, despite our inability to generate docking poses for S‐1 in our initial model (Figure 1), we were able to dock S‐1 into the space created by R‐1 in the LBP of our hRXRα‐R‐1 co‐crystal structure (Supporting Information). The contrast between this success and the docking studies highlights an imperfection of molecular docking on account of the dynamic behavior of protein folding and the need for caution when interpreting docking results. Nevertheless, in contrast to R‐1, our best docking pose for S‐1 placed the spiroketal ring system in a thermodynamically less‐favorable axial–equatorial conformation. Therefore, we logically assign 1‐ent1 to be R‐1 and 1‐ent2 to be S‐1, and tentatively speculate that the weaker activity observed for S‐1 in the FP assay may result from a protein‐induced fit of the spiroketal to the RXR LBP via the postulated axial–equatorial conformation.

Figure 3.

X‐ray co‐crystallography data. a) Ribbon representation of the X‐ray co‐crystal structure of R‐1 (orange stick) bound to the ligand‐binding pocket (LBP) of hRXRα (green ribbon) with the TIF2 co‐activator‐derived peptide (blue ribbon) PDB code: 5LYQ. b) Enlarged view of the hRXRα LBP with the amino acid side chains labelled and represented as sticks. c) Superimposition of R‐1 and final 2F o−F c electron density map (contoured at 1σ). d) Superimposition of the LBP region of hRXRα bound to R‐1 (protein in green, ligand in orange, PDB code: 5LYQ) and a documented full agonist (protein in red, ligand in cyan, PDB code: 40C7).28 The TIF2 peptide corresponding to PDB code 40C7 is shown in cyan. Participating helices/residues/atoms are labelled. Orange arrows indicate movement in protein conformation from an agonistic (red) to the folded state induced by R‐1 (green). The loop region connecting helix 11 (H11) to H12‐443GDTPID448 is hidden for clarity.

In search of a plausible structural basis for the RXR activity of our spiroketals, we superimposed the co‐crystal structure of hRXRα–R‐1–TIF2 with a previously published crystal structure of hRXRα–TIF2 bound to a potent full agonist (Figure 3 D).28 Compared to the full agonist, the binding of R‐1 results in a circa 1 Å displacement of the side chain of Leu436 in H11 and the C‐terminal region of H11, which would perturb H12 binding, and potentially destabilize coactivator peptide binding as a possible cause of the partial agonist effect observed in the FP data. A similar sequence of side‐chain displacements has been cited by Nahoum et al. to explain the partial agonist behavior of structurally different biaryl RXR ligands reported,42 thus hinting at a general mechanism for RXR partial agonism.

In conclusion, we report the structure‐based design, synthesis, and biochemical as well as structural evaluation of a bisbenzannulated spiroketal as a potent modulator of the RXRα gene transcription factor. Our work includes a rare co‐crystal structure of a spiroketal,20, 21 which is to the best of our knowledge the first of a benzannulated spiroketal bound to a protein target. We believe that the apparent RXR partial agonist behavior of our spiroketal contributes to establishing partial agonism43 as a concept for RXR.42, 44 Furthermore, the high structural homology of the LBP across the NR superfamily,41 combined with the structural versatility of spiroketals, suggests that spiroketals can be designed to selectively target other NR subtypes as forerunner to the designed modulation of other protein targets.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

We thank Joost van Dongen for assistance with the chiral column chromatography and performing MS measurements. Funding was granted by the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture, Science (Gravity program 024.001.035), ECHO grant 711011017, ECHO‐STIP grant 717.014.004 and CRC 1093.

M. Scheepstra, S. A. Andrei, M. Y. Unver, A. K. H. Hirsch, S. Leysen, C. Ottmann, L. Brunsveld, L.-G. Milroy, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 5480.

Contributor Information

Prof. Dr. Luc Brunsveld, Email: l.brunsveld@tue.nl

Dr. Lech‐Gustav Milroy, Email: l.milroy@tue.nl

References

- 1. Zheng Y., Tice C. M., Singh S. B., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 3673–3682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Perron F., Albizati K. F., Chem. Rev. 1989, 89, 1617–1661. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sperry J., Wilson Z. E., Rathwell D. C. K., Brimble M. A., Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010, 27, 1117–1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yoneda N., Fukata Y., Asano K., Matsubara S., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 15497–15500; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 15717–15720. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Butler B. B., Manda J. N., Aponick A., Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 1902–1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Farrell M., Melillo B., Smith A. B., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 232–235; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 240–243. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burke M. D., Schreiber S. L., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 46–58; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2004, 116, 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wilk W., Zimmermann T. J., Kaiser M., Waldmann H., Biol. Chem. 2010, 391, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wetzel S., Bon R. S., Kumar K., Waldmann H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 10800–10826; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 10990–11018. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barun O., Sommer S., Waldmann H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 3195–3199; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2004, 116, 3258–3261. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barun O., Kumar K., Sommer S., Langerak A., Mayer T. U., Müller O., Waldmann H., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 4773–4788. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sommer S., Kühn M., Waldmann H., Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008, 350, 1736–1750. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zinzalla G., Milroy L.-G., Ley S. V., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006, 4, 1977–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Milroy L.-G., Zinzalla G., Loiseau F., Qian Z., Prencipe G., Pepper C., Fegan C., Ley S. V., ChemMedChem 2008, 3, 1922–1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wetzel S., Klein K., Renner S., Rauh D., Oprea T. I., Mutzel P., Waldmann H., Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5, 581–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Egea P. F., Mitschler A., Moras D., Mol. Endocrinol. 2002, 16, 987–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.BioSolveIT GmbH, Sankt Augustin. http://www.biosolveit.de, LeadIT, version 2. 1. 3.

- 18.BioSolveIT GmbH, Sankt Augustin. http://www.biosolveit.de, SeeSar, version 5.3.

- 19. Ohtake Y., Sato T., Kobayashi T., Nishimoto M., Taka N., Takano K., Yamamoto K., Ohmori M., Yamaguchi M., Takami K., et al., J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 7828–7840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rizvi S. A., Tereshko V., Kossiakoff A. A., Kozmin S. A., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 3882–3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bourne Y., Sulzenbacher G., Radić Z., Aráoz R., Reynaud M., Benoit E., Zakarian A., Servent D., Molgó J., Taylor P., et al., Structure 2015, 23, 1106–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brasholz M., Sörgel S., Azap C., Reißig H.-U., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 3801–3814. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Brimble M. A., Flowers C. L., Trzoss M., Tsang K. Y., Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 5883–5896. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Barnard J. H., Collings J. C., Whiting A., Przyborski S. A., Marder T. B., Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 11430–11442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Evans R. M., Mangelsdorf D. J., Cell. 2014, 157, 255–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chiang K., Koo E. H., Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 54, 381–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dominguez M., Alvarez S., de Lera A. R., Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2017, 17, 631–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Scheepstra M., Nieto L., Hirsch A. K. H., Fuchs S., Leysen S., Lam C. V., in het Panhuis L., van Boeckel C. A. A., Wienk H., Boelens R., et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 6443–6448; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 6561–6566. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Scheepstra M., Leysen S., van Almen G. C., Miller J. R., Piesvaux J., Kutilek V., van Eenennaam H., Zhang H., Barr K., Nagpal S., et al., Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Schneider G., Drug Discovery Today Technol. 2013, 10, e453–e460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dawson M. I., Jong L., Hobbs P. D., Cameron J. F., Chao W., Pfahl M., Lee M.-O., Shroot B., Pfahl M., J. Med. Chem. 1995, 38, 3368–3383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sussman F., de Lera A. R., J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 6212–6219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. McLeod M. C., Brimble M. A., Rathwell D. C. K., Wilson Z. E., Yuen T.-Y., Pure Appl. Chem. 2011, 84, 1379–1390. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wilsdorf M., Reissig H.-U., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 4332–4336; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 4420–4424. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fuchs S., Nguyen H. D., Phan T. T. P., Burton M. F., Nieto L., de Vries-van Leeuwen I. J., Schmidt A., Goodarzifard M., Agten S. M., Rose R., et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 4364–4371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Love J. D., Gooch J. T., Benko S., Li C., Nagy L., Chatterjee V. K. K., Evans R. M., Schwabe J. W. R., J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 11385–11391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stafslien D. K., Vedvik K. L., De Rosier T., Ozers M. S., Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2007, 264, 82–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Voegel J. J., Heine M. J., Zechel C., Chambon P., Gronemeyer H., EMBO J. 1996, 15, 3667–3675. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Aitken H. R. M., Furkert D. P., Hubert J. G., Wood J. M., Brimble M. A., Org. Biomol. Chem. 2013, 11, 5147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Atkinson D. J., Brimble M. A., Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 811–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Huang P., Chandra V., Rastinejad F., Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2010, 72, 247–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nahoum V., Perez E., Germain P., Rodriguez-Barrios F., Manzo F., Kammerer S., Lemaire G., Hirsch O., Royer C. A., Gronemeyer H., et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 17323–17328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Burris T. P., Solt L. A., Wang Y., Crumbley C., Banerjee S., Griffett K., Lundasen T., Hughes T., Kojetin D. J., Pharmacol. Rev. 2013, 65, 710–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ohsawa F., Yamada S., Yakushiji N., Shinozaki R., Nakayama M., Kawata K., Hagaya M., Kobayashi T., Kohara K., Furusawa Y., et al., J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 1865–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary