Abstract

We have previously demonstrated that TGFβ Inducible Early Gene-1 (TIEG1), also known as KLF10, plays important roles in mediating skeletal development and homeostasis in mice. TIEG1 has also been identified in clinical studies as one of a handful of genes whose altered expression levels or allelic variations are associated with decreased bone mass and osteoporosis in humans. Here, we provide evidence for the first time that TIEG1 is involved in regulating the canonical Wnt signaling pathway in bone through multiple mechanisms of action. Decreased Wnt signaling in the absence of TIEG1 expression is shown to be in part due to impaired β-catenin nuclear localization resulting from alterations in the activity of AKT and GSK-3β. We also provide evidence that TIEG1 interacts with, and serves as a transcriptional co-activator for, Lef1 and β-catenin. Changes in Wnt signaling in the setting of altered TIEG1 expression and/or activity may in part explain the observed osteopenic phenotype of TIEG1 KO mice as well as the known links between TIEG1 expression levels/allelic variations and patients with osteoporosis.

INTRODUCTION

TGFβ Inducible Early Gene 1 (TIEG1) is a member of the Krüppel-like transcription factor family (KLF10) and was originally discovered in our laboratory as an early response gene in osteoblasts following TGFβ treatment (1). Since its discovery, we have demonstrated critical roles for TIEG1 in regulating a wide variety of cellular processes and molecular functions important for bone biology. These include modulation of the TGFβ, BMP, and estrogen signaling pathways (2–7) and regulation of osteoblast and osteoclast specific functions (8–11). Additionally, we have revealed roles for TIEG1 in regulating the expression and function of two different critical transcription factors in bone, Runx2 (12) and osterix (13). Finally, single nucleotide polymorphisms in the TIEG1 gene are associated with decreased volumetric bone mineral density at the femoral neck in men (14) and altered expression of TIEG1 has been observed in the bones of female osteoporotic patients (15). These laboratory and clinical studies implicate a central role for TIEG1 in maintaining normal skeletal homeostasis and bone health.

To better understand the functions of TIEG1 in vivo, we developed a TIEG1 knockout (KO) mouse model system (8). Examination of the skeleton of TIEG1 KO mice has revealed a female specific osteopenic phenotype characterized by decreased bone mineral density and content, in both trabecular and cortical compartments, compared to wild-type (WT) littermates (16,17). Mechanical testing of femurs isolated from TIEG1 KO mice indicated significant decreases in the strength of these long bones only in female animals (16,17). Further investigations aimed at better understanding the basis for the observed female-specific bone phenotype have revealed that TIEG1 expression is augmented by estradiol in bone cells (2), that the skeletal phenotype of female TIEG1 KO mice resembles that of an ovariectomized WT mouse (18) and that deletion of TIEG1 attenuates estrogen responsiveness throughout the mouse skeleton (18).

In previous studies, analyzing the global gene expression profiles of heart tissue isolated from TIEG1 KO mice, we identified alterations in multiple genes that participate in the Wnt signaling pathway (19). Other studies have also identified correlations between TIEG1 and Wnt pathway activity in other cell and tissue types (20–22) suggested that TIEG1 may play important roles in modulating this pathway. Canonical Wnt signaling occurs when a Wnt ligand interacts with a member of the Frizzled family of receptors and either LRP5 or LRP6. This interaction ultimately leads to inhibition of GSK3-mediated phosphorylation of β-catenin resulting in its stabilization and nuclear translocation. In the nucleus, β-catenin interacts with transcription factors, including members of the Tcf/Lef family, to regulate target gene expression. In the absence of a Wnt ligand signal, GSK3 phosphorylates β-catenin which targets it for proteasomal degradation leading to reduced levels of β-catenin in the nucleus and suppression of canonical Wnt signaling (23).

Since the early 2000s, the Wnt signaling pathway has gained significant interest in the field of bone biology following the observations that loss of function mutations in the LRP5 gene are associated with a low bone mass phenotype in humans (24). Subsequently, a single point mutation in the LRP5 gene was shown to result in an inherited high bone mass phenotype (25,26) due to enhanced Wnt signaling. These findings have been further validated in mouse models whereby deletion of the LRP5 gene leads to a decreased bone mass phenotype (27,28) while overexpression of a LRP5 variant carrying the same point mutation identified in families with high bone mass elicits a nearly identical phenotype in mice (29). Furthermore, conditional knockout of β-catenin in the osteoblasts or osteocytes of mice also results in a low bone mass phenotype while activation of β-catenin leads to dramatic increases in bone content (30–32). These seminal reports, in combination with a multitude of other studies over the past decade, have revealed essential roles for the Wnt signaling pathway and β-catenin function in mediating bone development, homeostasis and disease.

Given the essential functions of the Wnt pathway in regulating skeletal development and health, as well as our past studies indicating a link between TIEG1 expression and Wnt pathway activity, we sought to fully characterize the potential roles of TIEG1 in modulating Wnt signaling in bone. In this study, we have analyzed the expression levels of all 19 Wnt ligands, essential downstream mediators of the Wnt pathway, and a number of Wnt target genes in WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts during the course of differentiation. We also demonstrate that loss of TIEG1 expression results in suppression of Wnt pathway activity both in vitro and in vivo and provide evidence that TIEG1 enhances Wnt signaling by regulating β-catenin nuclear localization and by serving as a co-activator for Lef1 and β-catenin transcriptional activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal models

The generation and characterization of TIEG1 KO mice has been described previously (8). For this study, congenic C57BL/6 female WT and TIEG1 KO littermates were utilized (17). WT-TOPGAL and TIEG1 KO-TOPGAL mice were generated by crossing WT and TIEG1 KO animals with C57BL/6 TOPGAL expressing mice. TOPGAL mice contain a β-galactosidase transgene under the control of a Tcf/Lef/β-catenin inducible promoter allowing one to monitor the activity of the canonical Wnt pathway in vivo (33). This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The protocol was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (permit number: A9615).

Cell lines and culture conditions

Calvarial osteoblasts were isolated from 3-day-old neonatal WT and TIEG1 KO mouse pups as described previously (8,9). Briefly, neonates were euthanized using CO2, the calvarium were dissected out, cleaned of all tissue, rinsed in PBS and minced. Calvarium bone chips were subjected to 3 collagenase digestions and osteoblast cells isolated from the third digestion were plated in α-MEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gemini Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA, USA) and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and propagated in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Calvarial osteoblasts were differentiated in the same medium supplemented with 50 mg/l ascorbic acid and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate. Differentiation medium was changed every 3 days. All experiments utilizing calvarial osteoblasts were conducted within the first three passages and are representative of three independent WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblast cell lines. Mineralization assays were performed using Alizarin Red staining as previously described (8,12). U2OS cells were purchased from ATCC and were cultured in phenol red-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F12 medium (DMEM/F12) (ThermoFisher Scientific) containing 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic/antimycotic. For LiCl studies, cells were treated with a final concentration of 10 mM as previously described (34).

RNA isolation and real-time PCR

Calvarial osteoblasts were plated in triplicate at a density of ∼50% in 12-well plates and were allowed to proliferate until they reached 100% confluence (day 0) at which time osteoblast differentiation medium was added. On days 1, 6, 10, 14, 18, 21 and 26, total RNA was harvested from three independent WT and TIEG1 KO cell lines in triplicate using Trizol reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific). One μg of RNA was reverse transcribed using the iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and real-time PCR was performed in triplicate using a Bio-Rad iCycler and a PerfeCTa™ SYBR Green Fast Mix™ for iQ real-time PCR kit (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD) as specified by the manufacturer. Cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 30 s followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 3 s and 60°C for 30 s. Melt curves were generated to ensure amplification of a single PCR product. Quantitation of the PCR results was calculated based on the threshold cycle (Ct) following normalization to β-tubulin and averaged among genotypes. All PCR primers were designed using Primer3 software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/) and were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA). Primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Primer sets used in qRT-PCR and ChIP assays.

| Primer, 5΄ - 3΄ | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gene | Forward | Reverse |

| mWnt1 | CGCTTCCTCATGAACCTTCAC | TGGCGCATCTCAGAGAACAC |

| mWnt2 | TGGCTGAGTGGACTGCAGAGT | GTTGCAGTTCCAGCGATGCT |

| mWnt2b | CCAGACATCATGCGCTCAGTA | GGAACTGGTGCTGGCACTCT |

| mWnt3 | ACCGAGAGGGACCTGGTCTAC | TGGGTTGGGCTCACAAAAGT |

| mWnt3a | GAGACCCTGAGGCCACGTTAC | AGTAGACCAGGTCGCGTTCTG |

| mWnt4 | GTACCTGGCCAAGCTGTCATC | TTTCTCGCACGTCTCCTCTTC |

| mWnt5a | CCACGCTAAGGGTTCCTATGAG | ACGGCCTGCTTCATTGTTGT |

| mWnt5b | GCACCGTGGACAACACATCT | GGCAGTCTCTCGGCTACCTATC |

| mWnt6 | TTATGGATGCGCAGCACAAG | CTCGTTGTTGTGCAGTTGCA |

| mWnt7a | TGGACCACACTGCCACAGTT | GACGGCCTCGTTGTATTTGTC |

| mWnt7b | GCAGCTACCAGAAGCCTATGGA | TCGCAGTAGTTGGGCGACTT |

| mWnt8a | TCTGCCTGGTCAGTGAACAACT | TGGCGGTGTAGGTCAGATAGG |

| mWnt8b | TGCCCCGAGAGAGCTTTACA | CAAATGCTGTCTCCCGGTTAG |

| mWnt9a | CGTGGGTGTGAAGGTGATAAAG | ACACACCATGGCATTTGCAA |

| mWnt9b | GGGACCTGGTCTACATGGAAGA | GTGCCCGGAGAGTACTTGCT |

| mWnt10a | CGGAACAAAGTCCCCTACGA | CGAAAGCACTCTCTCGAAAACC |

| mWnt10b | ATGCGGATCCACAACAACAG | GCACTTCCGCTTCAGGTTTTC |

| mWnt11 | CTCCCCTGACTTCTGCATGAA | CTTGTTGCACTGCCTGTCTTG |

| mWnt16 | TCAGGAGTGCAGAAGCCAGTT | AAGTGGTAGTGGCGACCATACA |

| mDkk1 | TGCCTCCGATCATCAGACTGT | CTTGGACCAGAAGTGTCTTGCA |

| mSost | ACTTGTGCACGCTGCCTTCT | TGACCTCTGTGGCATCATTCC |

| mβ-catenin | GATGCAGCGACTAAGCAGGAA | GGAACCCAGAAGCTGCACTAGA |

| mLef1 | CTGGCAAGGTCAGCCTGTTTA | GTGTCGCCTGACAGTGAGGAT |

| mC-myc | CAGCTCGCCCAAATCCTGTA | CGAGTCCGAGGAAGGAGAGA |

| mCyclinD1 | AGAAGGAGATTGTGCCATCCA | CTCACAGACCTCCAGCATCCA |

| mCox2 | TGCAGAATTGAAAGCCCTCT | CCCCAAAGATAGCATCTGGA |

| mRunx2 | GCCGGGAATGATGAGAACTA | GGTGAAACTCTTGCCTCGTC |

| mβ-Tubulin | CTGCTCATCAGCAAGATCAGAG | GCATTATAGGGCTCCACCACAG |

| TOP FLASH ChIP | TCATGTCTGGATCCAAGCT | GCTGGAATTCGAGCTCCCA |

| Axin2 ChIP | TGCTTGCCACTGTTTGAAGTCAGC | GCCATGAACCCTTTTTGATCTTGC |

| Hdac4 ChIP | TGAAAGCACCGCTCATTCTCTGTG | GCTGCCTTAAACTTGGCATCAAAGG |

| Mmp20 ChIP | TTCCTTCTTAGTTTGCTTCACTGGAAA | CATGGTTGATTTCTTGGCTTCTGAC |

| Myc1 ChIP | TGAGAGGTGGAGAAAGAGATGTTCA | CCCCAGAGACACAAAAGGGAAGA |

| Runx2 ChIP | CGTAGTAGTACACAACGCCG | GTTTCGTGTCTGT CTTCCCC |

Transient transfection and luciferase assays

Calvarial osteoblasts or U2OS cells were plated at a density of 50% in 12-well plates in replicates of 6. As indicated, cells were transfected with 250 ng of the TOP FLASH reporter and/or various expression vectors (empty pcDNA4.0, Flag-tagged TIEG1, Flag-tagged Lef1, constitutively active β-catenin or Xpress-tagged TIEG1 domain expression constructs (35)) using Fugene-6 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) as specified by the manufacturer. Empty vector was added to transfections as necessary to normalize the total amount of DNA transfected across each condition. Twenty four hours following transfection, cells were lysed in passive lysis buffer (Promega, Madison, WI), lysates were quantitated for protein content and equal amounts of protein were used to measure luciferase activity using Luciferase Assay Reagent (Promega) and a Glomax-Dual luminometer (Promega).

β-Galactosidase (LacZ) staining of L5 vertebrae

Two-month-old WT- and TIEG1 KO-TOPGAL mice were sacrificed using CO2 and the L5 vertebrae were harvested from a total of 10 animals per genotype. The vertebrae were fixed, embedded, sectioned and stained for LacZ using standard protocols as previously described (36,37). Differences in LacZ staining between WT and KO mice were determined by LacZ positive cell counts as previously described (38,39), averaged among genotypes and normalized to TIEG1 KO counts.

Confocal microscopy and Duolink assays

Calvarial osteoblasts or U2OS cells were plated on coverslips at low confluence and allowed to adhere overnight. Cells were transfected as indicated or treated with LiCl for 24 h. Cells were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and washed twice with 1× PBS followed by permeabilization with 0.2% Triton-X in PBS for 30 min and blocked for an additional 30 min in heat-inactivated 5% FBS. Subsequently, cells were incubated with a polyclonal TIEG1 antibody produced by our laboratory (#992) and a monoclonal β-catenin antibody (clone 14/Beta-Catenin (RUO)) for 60 min. Cells were washed twice with PBS and stained with Texas Red- and FITC-conjugated secondary IgG Antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for an additional 60 minutes. DAPI was used as a counter stain and images were captured with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Quantitation of nuclear TIEG1 and β-catenin signals was performed using Image J software. The Duolink assay (DUO92101, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) employs the same protocol with the exception that following primary antibody incubation, coverslips are incubated with PLA probes (anti-rabbit and anti-mouse) for 1 h, ligated for 30 min and amplified for 100 min per the manufacturer's protocol. All steps were carried out at 37°C protected from light. Coverslips were mounted on slides with DAPI-containing mounting media and images were captured with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope.

Western blot and co-immunoprecipitation analyses

For western blotting, whole cell lysates were prepared by lysing cells in NETN buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 0.5% Nonidet P-40) and insoluble material was pelleted. Where indicated, nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared using a cell fractionation kit (Abcam) as specified by the manufacturer. Protein concentrations were determined using Bradford Reagent and 20 μg of total protein was separated using 7.5% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes, blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST for 1 h at room temperature and probed with primary antibodies in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies used were as follows: [total AKT: Cell Signaling, clone 9272 (1:1000); pAKT (S473): Cell Signaling, clone 9271 (1:1000); total GSK-3β (27C10): Cell Signaling, clone 9315 (1:1000); pGSK-3β (S21/9): clone 9331S (1:1000); total β-catenin: BD Biosciences, clone 14/Beta-Catenin (RUO) (1:1000); active β-catenin: Millipore, clone E87 (1:1000); C-MYC: Santa Cruz, SC-764, (1:200); COX2: Santa Cruz, SC-23984 (1:200); DKK1: Santa Cruz, SC-14949 (1:200); RUNX2: Santa Cruz, SC-10758 (1:200); αTubulin: Sigma, clone DM1A (1:100 000); Vinculin: Abcam ab129002 (1:2500); Lamin B: Abcam ab16048 (1:1000); GAPDH: Millipore MAB374 (1:4000) and Xpress: Thermo Fisher, clone R910-25]. Membranes were washed in TBST and incubated with secondary anti-rabbit or anti-mouse HRP conjugated antibodies (1:2000 in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBST) for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were again washed in TBST and visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) on a LI-COR Odyssey® Fc Imaging System.

For co-immunoprecipitation, U2OS cells were plated at a density of ∼50% in 100 mm tissue culture plates and transfected with 5 μg of a flag-tagged TIEG1 expression construct. Following 24 h of incubation, cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed in NETN buffer. Protein concentrations were determined and 500 μg of lysates were immunoprecipitated at 4°C overnight using 1 μg of either rabbit IgG or Flag antibody (clone M2, Sigma). Protein complexes were purified using protein G beads. Immunoprecipitated complexes, as well as 50 μg of whole cell extracts (WCEs), were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF and blocked in 5% milk overnight. Western blotting was performed using Lef1 (Cell Signaling; clone C12A5) and β-catenin primary antibodies.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays

U2OS cells were plated at a density of approximately 50% in 100 mm tissue culture plates and transfected in triplicate with 5 μg of both the TOP FLASH reporter construct and indicated flag-tagged expression constructs. Following incubation for 24 h, ChIP assays were performed as previously described (2). Immunoprecipitations were carried out using 1 μg of Flag antibody. Inputs were generated as above excluding the antibody immunoprecipitation. Semi-quantitative PCR and quantitative Real-Time PCR were conducted in triplicate on all samples and a representative data set is shown. Primers used in the PCR reactions were designed to amplify the Tcf/Lef enhancer region in the TOP FLASH reporter construct and are listed in Table 1. Quantitative PCR values were calculated based on the threshold cycle (Ct), normalized to input controls and compared to IgG immunoprecipitated samples. ChIP assays for canonical Wnt target genes were performed using U2OS cells that were transiently transfected with empty pcDNA4, Flag-tagged Lef1 or Flag-tagged TIEG1 expression vectors as described above. PCR primers surrounding previously identified Lef1/β-catenin enhancer elements in the Runx2, Myc1, Axin2, Hdac4 and Mmp20 genes (40,41) are listed in Table 1.

Statistics

For all real-time PCR, luciferase reporter construct assays, β-galactosidase staining and chromatin immunoprecipitation assays, a two-sided Student's t-test was utilized. P-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Data presented are mean of triplicate experiments ± standard error. Calculations were conducted using Excel.

RESULTS

TIEG1 modulates the expression of Wnt pathway genes in osteoblasts

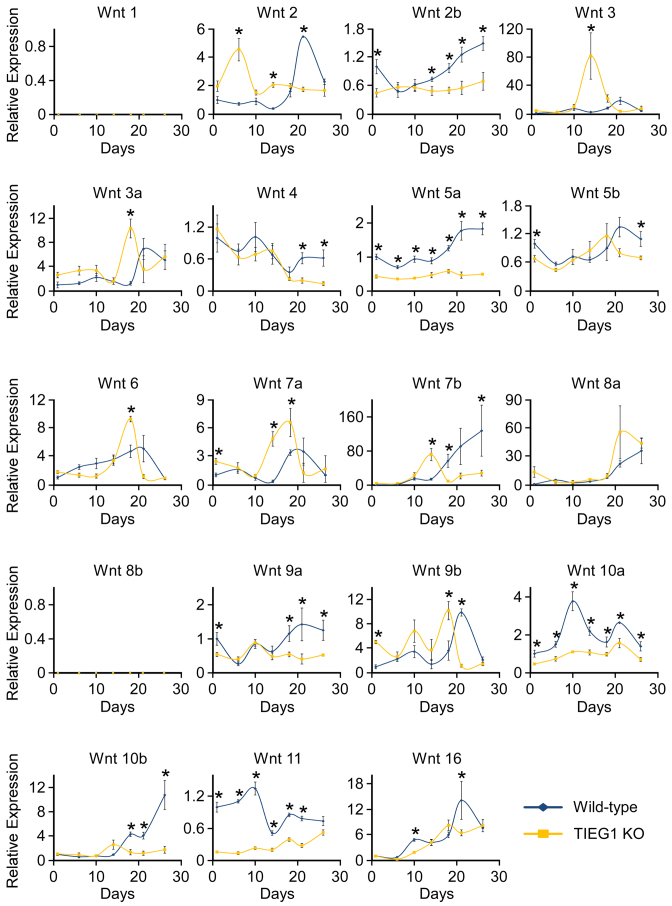

Previous studies from our laboratory and others have suggested that TIEG1 may be involved in modulating Wnt signaling (19–22). We therefore sought to characterize the expression levels of all Wnt ligands, antagonists of Wnt pathway activity, transcription factor mediators and well characterized target genes during the course of WT and TIEG1 KO osteoblast differentiation. Multiple gene expression patterns were observed for the Wnt ligands in both genotypes, and loss of TIEG1 expression was shown to impact both canonical and non-canonical Wnt ligands, as shown in Figure 1. In general, most Wnts trended to increase in expression during the course of differentiation in WT cells with the exception of Wnt 4 and Wnt 11 which trended towards decreased expression over time (Figure 1). Interestingly, the expression of Wnts 2, 6, 7a, 9b and 10a dropped during terminal osteoblast differentiation (Figure 1). A number of differences in the expression levels of Wnt ligands were also detected between WT and TIEG1 KO cells. Specifically, Wnts 2b, 5a, 10a and 11 exhibited significantly decreased expression at the majority of differentiation time points examined in TIEG1 KO cells compared to WT controls (Figure 1). Wnts 1 and 8b were not expressed at any time point analyzed in either WT or TIEG1 KO osteoblasts (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Expression of Wnt ligands in WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts. Three independent WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblast cell lines were differentiated in culture for indicated number of days. Total RNA was isolated and RT-PCR was performed for indicated Wnt ligands. * denotes significant differences (P < 0.05) between WT and TIEG1 KO cells at a given time point.

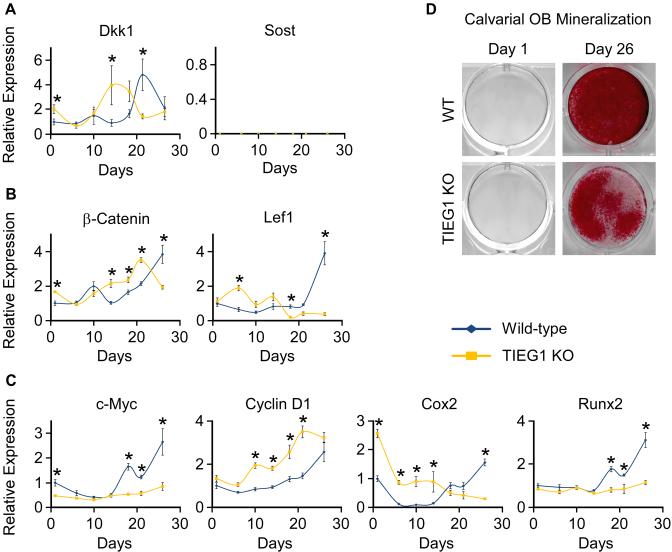

We next examined the expression of two potent secreted inhibitors of the Wnt pathway, Dkk1 and Sost. Dkk1 was more highly expressed in undifferentiated TIEG1 KO cells, but in general normalized its expression levels to that of WT cells during the course of differentiation (Figure 2A). Sost mRNA levels were undetectable in both WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts (Figure 2A). β-Catenin and Lef1, transcription factors responsible for mediating canonical Wnt signaling, displayed decreased expression in TIEG1 KO cells following terminal differentiation (Figure 2B). Finally, three out of four classic canonical Wnt target genes (c-Myc, Cox2 and Runx2) exhibited decreased expression in differentiated TIEG1 KO cells compared to WT controls (Figure 2C). Representative alizarin red stained images depicting mineralization of WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblast are shown in Figure 2D. These data demonstrate that loss of TIEG1 expression results in delayed osteoblast differentiation, effects that may result from alterations in canonical Wnt pathway activity.

Figure 2.

Expression of Wnt pathway modulators and target genes in WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts. Three independent WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblast cell lines were differentiated in culture for indicated number of days. Total RNA was isolated and RT-PCR was performed for inhibitors of Wnt signaling (A), transcriptional mediators of Wnt signaling (B) and Wnt target genes (C). (D) Representative images of alizarin red stained WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts prior to and following differentiation. * denotes significant differences (P < 0.05) between WT and TIEG1 KO cells at a given time point.

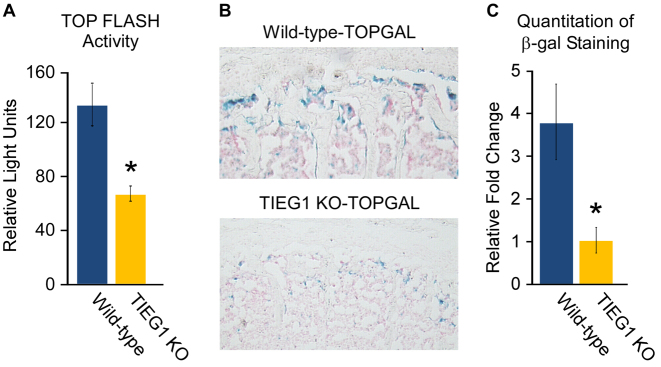

Loss of TIEG1 expression reduces canonical Wnt pathway activity in vitro and in vivo

In order to further address the role of TIEG1 in mediating Wnt signaling, we analyzed the activity of a TOP FLASH luciferase reporter construct in WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts. The TOP FLASH reporter contains multiple copies of Tcf/Lef binding sites and is used to assess the transcriptional activity of Tcf, Lef and β-catenin in cells. As shown in Figure 3A, the activity of this reporter construct was significantly diminished in TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts. We next crossed our WT and TIEG1 KO mice with the TOPGAL transgenic mouse model which expresses the β-galactosidase gene under the control of a Tcf/Lef and β-catenin inducible promoter. β-galactosidase (LacZ) staining (blue) of the L5 vertebrae isolated from 3-month-old WT-TOPGAL and TIEG1 KO-TOPGAL mice (Figure 3B) revealed significant decreases in canonical Wnt pathway activity in TIEG1 deficient animals (Figure 3C). These data further confirm a role for TIEG1 in mediating canonical Wnt pathway activity in osteoblast cells in vitro and within the mouse skeleton in vivo and formed the basis for the focus of this manuscript of the mechanisms by which TIEG1 modulates canonical Wnt pathway activity.

Figure 3.

Wnt pathway activity in calvarial osteoblasts and bones of TIEG1 KO mice. (A) TOP FLASH reporter construct activity in WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblast cells. (B) LacZ staining in sections of L5 vertebrae isolated from WT-TOPGAL and TIEG1 KO-TOPGAL mice. Blue staining represents cells with active Wnt signaling. (C) Graph depicting quantitation of LacZ staining in 10 WT-TOPGAL and 10 TIEG1 KO-TOPGAL mice. * denotes significance at P < 0.05 relative to WT controls.

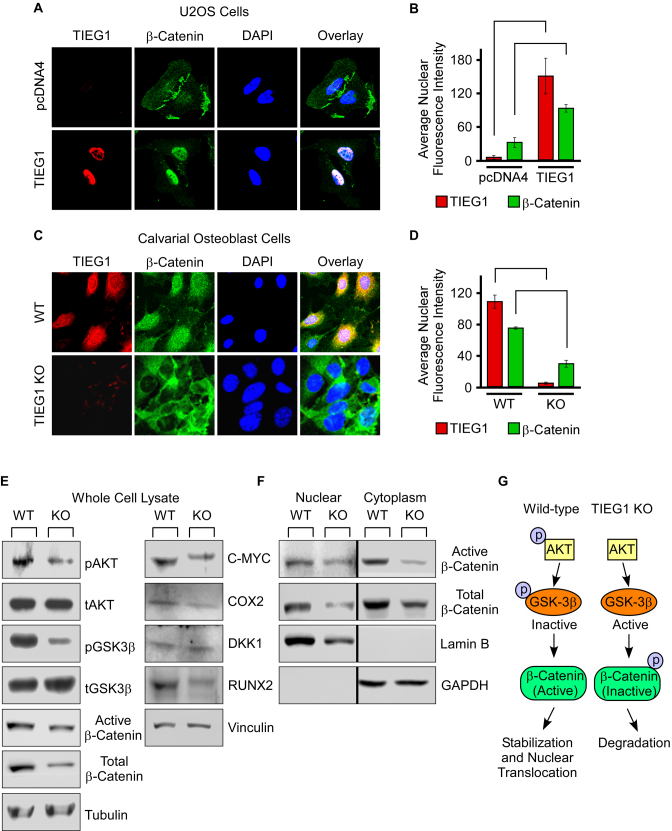

TIEG1 expression enhances β-catenin nuclear localization

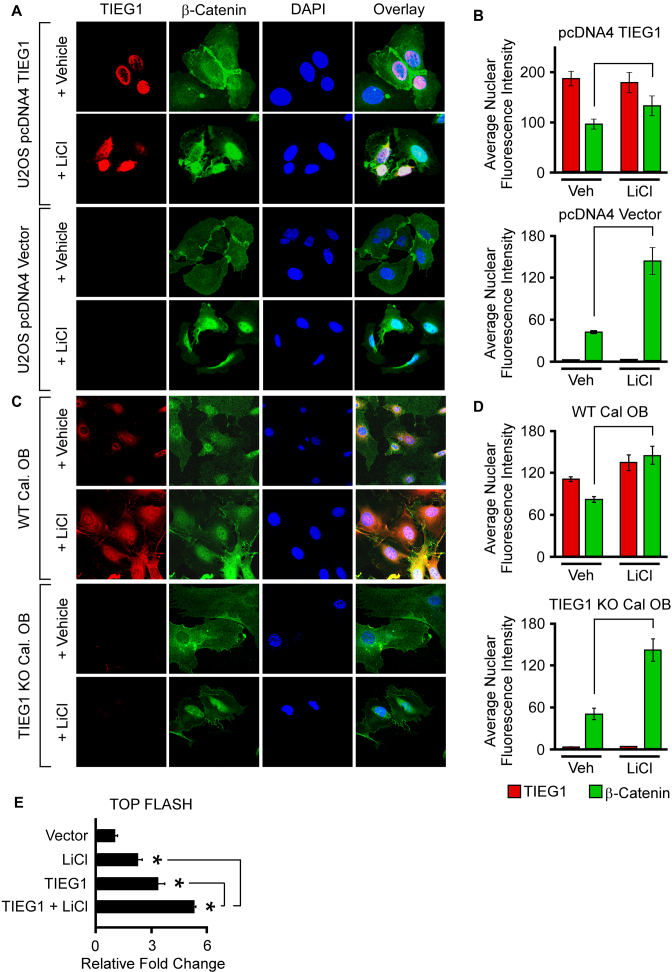

Based on the observation that TIEG1 KO-TOPGAL mice display decreased β-galactosidase activity in the L5 vertebrae, we speculated that loss of TIEG1 expression may impact β-catenin expression or sub-cellular localization. To address this possibility, we transiently expressed TIEG1 in U2OS osteosarcoma cells and examined the impact of TIEG1 expression on β-catenin protein levels and nuclear localization via confocal microscopy. As shown in Figure 4A and B, the expression of TIEG1 in U2OS cells lead to significant increases in the translocation of β-catenin from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. These results were confirmed in WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts as shown in Figure 4C and D. As can be appreciated visually, β-catenin exhibited both cytoplasmic and nuclear localization in WT cells but was primarily restricted to the cytoplasm in TIEG1 KO cells (Figure 4C). Quantification of confocal images demonstrated that there was significantly less β-catenin localized to the nucleus in TIEG1 KO osteoblasts compared to WT controls (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Impact of TIEG1 on β-catenin nuclear translocation. (A) U2OS cells were transfected with an empty vector (pcDNA4) or a TIEG1 expression vector and over-expressed TIEG1 protein (red) and endogenous β-catenin protein (green) were detected by immunofluorescence. DAPI staining (blue) indicates nuclei. (B) Quantitation of nuclear TIEG1 and β-catenin protein in U2OS cells transfected with an empty vector or TIEG1 expression construct. (C) Sub-cellular localization of endogenous TIEG1 (red) and β-catenin (green) in WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts. (D) Quantitation of nuclear TIEG1 and β-catenin protein in WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts. Western blots depicting expression levels of indicated proteins in whole cell lysates (E) or nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts (F) obtained from WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblast cells. (G) Model depicting impact of TIEG1 on AKT/GSK-3β signaling and nuclear localization of β-catenin.

We have previously determined that phosphorylation of AKT is suppressed in TIEG1 KO bone marrow stromal cells (data not shown). Since pAKT is known to phosphorylate, and thereby inhibit, GSK-3β (42), and since inhibition of GSK-3β enhances nuclear localization of β-catenin, we sought to determine if this signal transduction pathway was suppressed in TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts relative to WT controls. As shown in Figure 4E, TIEG1 KO cells displayed decreased levels of phospho-AKT and phospho-GSK-3β compared to WT cells. These changes were associated with decreased levels of both active and total β-catenin in TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts (Figure 4E). Given these findings, we next examined the protein expression levels of a number of canonical Wnt target genes in whole cell lysates of WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts. As shown in the right panel of Figure 4E, loss of TIEG1 expression resulted in decreased protein levels of C-MYC, COX2 and RUNX2. There was a trend towards slight increases in DKK1, an inhibitor of Wnt signaling, in TIEG1 KO osteoblasts (Figure 4E). Tubulin and Vinculin are shown as protein loading controls. Given the results of confocal microscopy in which decreased nuclear localization of β-catenin was observed in TIEG1 KO cells, we also examined the protein expression levels of active and total β-catenin in nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts. The protein levels of both active and total β-catenin were decreased in both nuclear and cytoplasmic lysates of TIEG1 KO cells relative to WT controls (Figure 4F). Lamin B and GAPDH were used as nuclear and cytoplasmic loading controls respectively (Figure 4F). These data demonstrate that loss of TIEG1 expression decreases Akt signaling resulting in decreased phosphorylation, and therefore activation, of GSK-3β leading to decreased nuclear localization of active β-catenin as depicted in the model shown in Figure 4G.

In light of these observed defects in β-catenin nuclear localization in the absence of TIEG1 expression, we next sought to determine if forced nuclear localization of β-catenin with lithium chloride (LiCl) could restore Wnt pathway activity. Lithium chloride is a known inhibitor of GSK-3β and therefore functions as an activator of Wnt signaling by stabilizing β-catenin and enhancing β-catenin nuclear translocation (43). As previously shown, over-expression of TIEG1 in U2OS cells was associated with increased levels of nuclear β-catenin protein and LiCl treatment resulted in significant increases in nuclear localization of β-catenin (Figure 5A and B). The effects of LiCl were more dramatic in non-TIEG1 transfected cells due to the decreased basal levels of nuclear β-catenin in the absence of TIEG1 expression (Figure 5A and B). The effects of LiCl on β-catenin nuclear localization were also examined in WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts. As with the results obtained in U2OS cells, LiCl treatment resulted in significant increases in nuclear localization of β-catenin in both WT and TIEG1 KO cells (Figure 5C and D). In spite of the fact that β-catenin was localized to the nucleus in U2OS cells following LiCl treatment, expression of TIEG1 further increased the activity of the TOP FLASH reporter construct beyond that of LiCl treatment alone (Figure 5E). These results provide evidence that TIEG1 not only modulates β-catenin nuclear localization, but may also function to further enhance the transcriptional effects of β-catenin once in the nucleus.

Figure 5.

Effect of LiCl on β-catenin nuclear localization and activation of the TOP FLASH reporter in the presence and absence of TIEG1 expression. (A) U2OS cells were transfected with an empty vector (pcDNA4) or a TIEG1 expression vector and subsequently treated with vehicle control or LiCl for 24 h. Over-expressed TIEG1 protein (red) and endogenous β-catenin protein (green) were detected by immunofluorescence. DAPI staining (blue) indicates nuclei. (B) Quantitation of nuclear TIEG1 and β-catenin protein in U2OS cells transfected with an empty vector or TIEG1 expression construct. (C) Confocal microscopy images depicting endogenous levels of TIEG1 protein (red) and β-catenin protein (green) in WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts. (D) Quantitation of nuclear TIEG1 and β-catenin protein in WT and TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts. (E) TOP FLASH reporter activity in U2OS cells that were co-transfected with empty vector (pcDNA4) or a TIEG1 expression vector and treated with or without LiCl as indicated. * denotes significance at P < 0.05 relative to empty vector controls.

TIEG1 serves as a co-activator for Lef1 and β-catenin

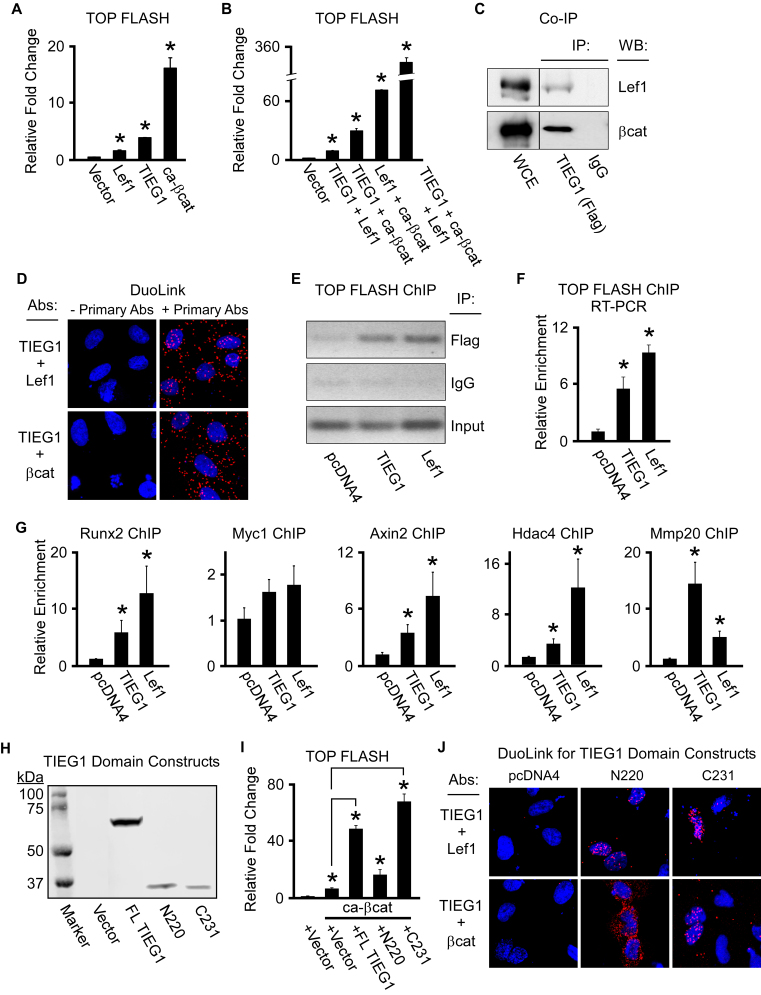

Given the above findings, we next determined the effects of TIEG1 on Lef1 and β-catenin mediated activation of the TOP FLASH reporter construct. As expected, co-transfection of either Lef1 or a constitutively active form of β-catenin (ca-β-catenin) with the TOP FLASH reporter construct into U2OS cells resulted in induction of luciferase activity (Figure 6A). Transfection of TIEG1 with the TOP FLASH reporter also resulted in induction of luciferase activity to levels greater than that of Lef1, but less than that of ca-β-catenin (Figure 6A). Co-transfection of TIEG1 with either Lef1 or ca-β-catenin resulted in further induction of the TOP FLASH reporter construct. These results were magnified when all three transcription factors were expressed together (Figure 6B). Since TIEG1 was able to serve as a co-activator for Lef1 and ca-β-catenin, we next determined if TIEG1 could interact with either of these factors. As shown in Figure 6C, co-immunoprecipitation assays revealed that TIEG1 associates with both Lef1 and ca-β-catenin in U2OS cells. Additionally, we employed a Duolink proximity assay to confirm these findings in live cells. As indicated by fluorescent red spots, TIEG1 was shown to associate with both Lef1 and β-catenin (Figure 6D). Furthermore, transient ChIP assays revealed that TIEG1, like Lef1, is enriched on Tcf/Lef enhancer elements encoded within the TOP FLASH reporter construct (Figure 6E and F). TIEG1 was also shown to associate with Tcf/Lef enhancer elements encoded within known canonical Wnt target genes such as Runx2, Myc1, Axin2, Hdac4 and Mmp20 (Figure 6G).

Figure 6.

TIEG1 interacts with and serves as a co-activator for Lef1 and β-catenin. (A and B) TOP FLASH reporter construct activity in U2OS cells transfected with empty vector or TIEG1, Lef1 and constitutively active β-catenin (ca-β-cat) expression vectors as indicated. (C) Co-immunoprecipitation assay in U2OS cells co-transfected with a flag-tagged TIEG1 expression construct and a Lef1 or β-catenin expression construct. Non-immunoprecipitated whole cell extracts (WCE) are shown as a loading control. (D) Duolink assays depicting interaction of TIEG1 with Lef1 and β-catenin (red fluorescent spots) in transiently transfected U2OS cells. Assays in which the primary antibodies targeting TIEG1, Lef1 and β-catenin were excluded are shown as negative controls. (E and F) Transient chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays in U2OS cells indicating TIEG1 and Lef1 association with Tcf/Lef elements in the TOP FLASH reporter construct by both semi-quantitative (E) and real-time PCR (F). (G). ChIP assays in U2OS cells transfected with TIEG1 or Lef1 expression vectors demonstrating enrichment of TIEG1 and Lef1 on known Tcf/Lef enhancer elements encoded within endogenous canonical Wnt target genes. All ChIP data were normalized using input samples. (H) Western blot indicating protein expression levels of full-length (FL) TIEG1 or N-terminal (N220) and C-terminal (C231) domains of TIEG1 following transfection into U2OS cells. (I) TOP FLASH reporter construct activity in U2OS cells transfected with a constitutively active β-catenin expression vector (ca-βcat) and indicated TIEG1 expression vectors. * denotes significance at P < 0.05 relative to empty vector controls. (J). Duolink assays depicting interaction of the N- and C-terminal domains of TIEG1 with Lef1 and β-catenin (red fluorescent spots) in transiently transfected U2OS cells. Empty vector (pcDNA4) transfected cells are shown as negative controls.

To determine the domain of TIEG1 that is responsible for serving as a co-activator for β-catenin, we analyzed the impact of full-length TIEG1, the N-terminus of TIEG1 (the first 220 amino acids (N220)) and the C-terminus of TIEG1 (the last 231 amino acids (C231)) on TOP FLASH reporter activity. The N-terminus of TIEG1 encodes several SH3 domains which are known to interact with co-factors to enhance or repress TIEG1 transcriptional activity. The C-terminal domain encodes three C2H2 type zinc fingers which are necessary for DNA binding and which also play roles in mediating co-factor interactions. The protein expression levels between the N- and C-terminal TIEG1 domain constructs were nearly identical to one another when transfected into U2OS cells (Figure 6H). As shown in Figure 6I, the C-terminal domain of TIEG1 is essential for co-activation of the TOP FLASH reporter construct as little to no activity was observed with the N-terminal construct. Interestingly, both the N- and C-terminal domains of TIEG1 were shown to interact with Lef1 and β-catenin using Duolink assays (Figure 6J). The C-terminal TIEG1 expression construct primarily interacted with Lef1 and β-catenin in the nucleus (Figure 6J). However, the N-terminal domain of TIEG1 only interacted with β-catenin in the cytoplasm likely explaining why the N-terminus does not function to co-activate β-catenin transcriptional activity in a TOP FLASH reporter assay (Figure 6I). These data demonstrate that TIEG1 might be part of a transcriptional complex with Lef1 and β-catenin and is capable of magnifying the transcriptional activation of Tcf/Lef enhancer elements in osteoblast cells.

DISCUSSION

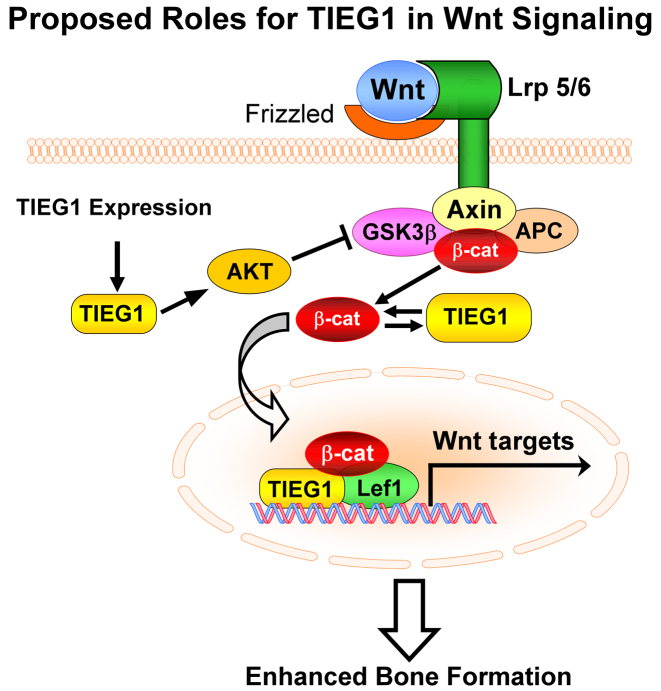

In the present study, we have demonstrated that loss of TIEG1 expression in osteoblasts results in altered expression of multiple Wnt ligands, a number of different activators/inhibitors of the signaling pathway and well characterized downstream canonical target genes. We have also shown that β-catenin-mediated signaling is significantly suppressed in TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblast cells in vitro and in the skeletons of TIEG1 KO mice in vivo. Furthermore, we have established that TIEG1 expression levels are associated with increased nuclear localization of β-catenin, an effect that is mediated in part by TIEG1's ability to stabilize β-catenin protein through activation of AKT and inhibition of GSK-3β. In addition to modulating β-catenin nuclear localization, we also reveal that TIEG1 interacts with Lef1 and β-catenin on Tcf/Lef enhancer elements resulting in enhancement of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway in osteoblasts. A model summarizing these findings is depicted in Figure 7. Taken together, these results demonstrate that TIEG1 functions through dual mechanisms to promote Wnt signaling; one, through enhancing β-catenin nuclear localization and two, through serving as part of a co-activator complex with Lef1 and β-catenin to increase transcription of target genes.

Figure 7.

Model depicting the mechanisms by which TIEG1 modulates canonical Wnt pathway activity in osteoblasts.

Cytoplasmic β-catenin protein is a core component of the Wnt signaling pathway (44). In the absence of a Wnt ligand signal, β-catenin is routinely targeted for proteasomal degradation by GSK-3β mediated phosphorylation (23,45). Activation of the Wnt signaling pathway occurs when a Wnt ligand interacts with LRP5 or LRP6 and a member of the frizzled receptor family of 7-transmembrane proteins (23). This interaction triggers a series of events that ultimately results in stabilization and nuclear localization of β-catenin protein through inhibition of GSK-3β kinase activity (23,45). Our data indicate that deletion of TIEG1 in osteoblasts results in altered expression levels of a number of different Wnts, including canonical and non-canonical Wnts, both in proliferating osteoblasts and during the course of differentiation. We also observed changes in the expression levels of Dkk1, an inhibitor of the Wnt pathway, as well as the downstream mediators, Lef1 and β-catenin, in TIEG1 KO cells. However, there was no clear cut expression pattern changes in these genes as some were more highly expressed in TIEG1 KO cells while others were more lowly expressed suggesting that these alterations are unlikely to completely explain the observed inhibition of Wnt signaling in the absence of TIEG1 expression.

Since nuclear localization and activation of β-catenin is an essential component of the canonical Wnt pathway, we assessed the impact of TIEG1 on mediating this process. Strikingly, TIEG1 KO calvarial osteoblasts contain very low levels of nuclear β-catenin protein compared to WT controls and expression of TIEG1 in U2OS osteosarcoma cells resulted in substantial β-catenin nuclear localization. Further, loss of TIEG1 expression in mice was shown to significantly inhibit canonical Wnt pathway activity in the skeleton. For these reasons, we choose to focus our studies on the roles of TIEG1 in modulating canonical Wnt pathway activity. In multiple cell types, AKT is known to phosphorylate, and thereby inhibit, GSK-3β, resulting in stabilization and nuclear localization of β-catenin (46–51). Our data indicate that loss of TIEG1 expression in osteoblasts results in suppression of AKT signaling and enhancement of GSK-3β activity. Alterations in this signaling cascade ultimately result in decreased levels of β-catenin within the nucleus of osteoblasts. As expected, these effects are associated with decreased protein levels of Wnt target genes such as C-MYC, COX2 and RUNX2 in TIEG1 KO osteoblasts.

Pharmacologic inhibition of GSK-3β using lithium chloride is known to increase β-catenin nuclear localization and enhance Wnt signaling in vitro and in vivo (52,53). We therefore determined if lithium chloride could restore β-catenin nuclear localization and Wnt pathway activity in the absence of TIEG1 expression. Our data demonstrate that lithium chloride induces significant increases in β-catenin nuclear translocation in the absence of TIEG1 expression in both U2OS and calvarial osteoblast cells. As expected, lithium chloride treatment increased Wnt pathway activation as indicated by induction of the TOP FLASH reporter construct. These effects were similar to that of TIEG1 expression which resulted in significant increases in reporter activity. However, expression of TIEG1 and co-treatment with lithium chloride further enhanced TOP FLASH activity to levels greater than that of either TIEG1 or lithium chloride alone. These results suggest that TIEG1 has additional functions within the cell nucleus to enhance Wnt pathway activity that extend beyond its role in modulating β-catenin nuclear localization.

Once in the nucleus, β-catenin interacts with DNA bound members of the Tcf/Lef family of transcription factors to enhance target gene expression (54,55). Given our data demonstrating reduced Wnt pathway activity in TIEG1 KO mouse bones and osteoblasts, as well as our observations that TIEG1 enhances Wnt pathway activity even in the presence of lithium chloride treatment, we next assessed the ability of TIEG1 to serve as a co-activator for Lef1 and β-catenin. Our studies revealed that overexpression of TIEG1 alone in osteoblast cells results in significant induction of the TOP FLASH reporter construct and elicits synergistic effects when co-expressed with Lef1 and/or β-catenin. We also demonstrated that TIEG1 interacts with both Lef1 and β-catenin proteins suggesting that it associates with these factors as part of a larger transcriptional complex on Tcf/Lef enhancer elements encoded within classic canonical Wnt target genes. Through the use of TIEG1 domain expression constructs, we provide evidence that the C-terminal domain of TIEG1 is responsible for this transactivation function. The involvement of TIEG1's C-terminus in regulating Tcf/Lef enhancer element activity is not surprising since this region contains the zinc-finger DNA binding domain (1,5) and has previously been shown to be necessary for its transactivation potential (56).

In summary, the present data are the first to report on a role for TIEG1 in modulating the Wnt signaling pathway in bone. Our studies demonstrate that deletion of TIEG1 is associated with alterations in the expression levels of multiple Wnt ligands and downstream mediators of the pathway resulting in suppression of canonical Wnt signaling in osteoblast cells and throughout the mouse skeleton. TIEG1 is shown to enhance Wnt signaling through at least two different mechanisms; one by suppressing GSK-3β activity and inducing β-catenin nuclear localization, and two by serving as a co-activator for Lef1 and β-catenin transcriptional activity (Figure 7). Given the importance of Wnt signaling for skeletal development and bone homeostasis, and the present data linking a role for TIEG1 in mediating this pathway, it is likely that alterations in Wnt signaling contribute to the observed osteopenic phenotype of TIEG1 KO mice. Based on these observations, it is of interest to determine if therapeutic interventions which enhance Wnt signaling will reverse the well characterized bone defects of TIEG1 KO mice. Furthermore, it is possible that such therapies would also be relevant for the treatment of osteoporosis in individuals with TIEG1 polymorphisms or altered TIEG1 expression levels as has been previously reported (14,15).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The overall study was conceived and designed by M. Subramaniam and J.R. Hawse; M. Cicek, K.S. Pitel, E.S. Bruinsma, M.H. Nelson Holte and S.G. Withers performed the experiments and analyzed the data; N.M. Rajamannan, F.J. Secreto and K. Venuprasad provided essential reagents, technical details and experimental guidance; M. Subramaniam and J.R. Hawse wrote the paper.

The authors would like to thank Dr Thomas C. Spelsberg for his excellent career mentorship, support, and helpful suggestions. We would also like to acknowledge Drs. Sundeep Khosla and David Monroe for providing us with the TOP FLASH luciferase reporter construct and Dr Jennifer Westendorf for the Lef1 and ca-β-catenin expression constructs.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health [R01 DE14036 to J.R.H. and M.S. and ARRA award 3RO1 HL 085591-02S10 to NMR]; Mayo Foundation. The open access publication charge for this paper has been waived by Oxford University Press - NAR.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Subramaniam M., Harris S.A., Oursler M.J., Rasmussen K., Riggs B.L., Spelsberg T.C.. Identification of a novel TGF-beta-regulated gene encoding a putative zinc finger protein in human osteoblasts. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995; 23:4907–4912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hawse J.R., Subramaniam M., Monroe D.G., Hemmingsen A.H., Ingle J.N., Khosla S., Oursler M.J., Spelsberg T.C.. Estrogen receptor beta isoform-specific induction of transforming growth factor beta-inducible early gene-1 in human osteoblast cells: an essential role for the activation function 1 domain. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008; 22:1579–1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hefferan T.E., Reinholz G.G., Rickard D.J., Johnsen S.A., Waters K.M., Subramaniam M., Spelsberg T.C.. Overexpression of a nuclear protein, TIEG, mimics transforming growth factor-beta action in human osteoblast cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2000; 275:20255–20259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hefferan T.E., Subramaniam M., Khosla S., Riggs B.L., Spelsberg T.C.. Cytokine-specific induction of the TGF-beta inducible early gene (TIEG): regulation by specific members of the TGF-beta family. J. Cell Biochem. 2000; 78:380–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Johnsen S.A., Subramaniam M., Janknecht R., Spelsberg T.C.. TGFbeta inducible early gene enhances TGFbeta/Smad-dependent transcriptional responses. Oncogene. 2002a; 21:5783–5790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Johnsen S.A., Subramaniam M., Katagiri T., Janknecht R., Spelsberg T.C.. Transcriptional regulation of Smad2 is required for enhancement of TGFbeta/Smad signaling by TGFbeta inducible early gene. J. Cell Biochem. 2002b; 87:233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnsen S.A., Subramaniam M., Monroe D.G., Janknecht R., Spelsberg T.C.. Modulation of transforming growth factor beta (TGFbeta)/Smad transcriptional responses through targeted degradation of TGFbeta-inducible early gene-1 by human seven in absentia homologue. J. Biol. Chem. 2002c; 277:30754–30759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Subramaniam M., Gorny G., Johnsen S.A., Monroe D.G., Evans G.L., Fraser D.G., Rickard D.J., Rasmussen K., van Deursen J.M., Turner R.T. et al. . TIEG1 null mouse-derived osteoblasts are defective in mineralization and in support of osteoclast differentiation in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005; 25:1191–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Subramaniam M., Hawse J.R., Bruinsma E.S., Grygo S.B., Cicek M., Oursler M.J., Spelsberg T.C.. TGFbeta inducible early gene-1 directly binds to, and represses, the OPG promoter in osteoblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010; 392:72–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Subramaniam M., Hawse J.R., Rajamannan N.M., Ingle J.N., Spelsberg T.C.. Functional role of KLF10 in multiple disease processes. BioFactors (Oxford, England). 2010; 36:8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cicek M., Vrabel A., Sturchio C., Pederson L., Hawse J.R., Subramaniam M., Spelsberg T.C., Oursler M.J.. TGF-β inducible early gene 1 regulates osteoclast differentiation and survival by mediating the NFATc1, AKT, and MEK/ERK signaling pathways. PLoS One. 2011; 6:e17522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hawse J.R., Cicek M., Grygo S.B., Bruinsma E.S., Rajamannan N.M., van Wijnen A.J., Lian J.B., Stein G.S., Oursler M.J., Subramaniam M. et al. . TIEG1/KLF10 modulates Runx2 expression and activity in osteoblasts. PLoS One. 2011; 6:e19429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Subramaniam M., Pitel K.S., Withers S.G., Drissi H., Hawse J.R.. TIEG1 enhances Osterix expression and mediates its induction by TGFbeta and BMP2 in osteoblasts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2016; 470:528–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yerges L.M., Klei L., Cauley J.A., Roeder K., Kammerer C.M., Ensrud K.E., Nestlerode C.S., Lewis C., Lang T.F., Barrett-Connor E. et al. . Candidate gene analysis of femoral neck trabecular and cortical volumetric bone mineral density in older men. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010; 25:330–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hopwood B., Tsykin A., Findlay D.M., Fazzalari N.L.. Gene expression profile of the bone microenvironment in human fragility fracture bone. Bone. 2009; 44:87–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bensamoun S.F., Hawse J.R., Subramaniam M., Ilharreborde B., Bassillais A., Benhamou C.L., Fraser D.G., Oursler M.J., Amadio P.C., An K.N. et al. . TGFbeta inducible early gene-1 knockout mice display defects in bone strength and microarchitecture. Bone. 2006; 39:1244–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hawse J.R., Iwaniec U.T., Bensamoun S.F., Monroe D.G., Peters K.D., Ilharreborde B., Rajamannan N.M., Oursler M.J., Turner R.T., Spelsberg T.C. et al. . TIEG-null mice display an osteopenic gender-specific phenotype. Bone. 2008; 42:1025–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hawse J.R., Pitel K.S., Cicek M., Philbrick K.A., Gingery A., Peters K.D., Syed F.A., Ingle J.N., Suman V.J., Iwaniec U.T. et al. . TGFbeta inducible early gene-1 plays an important role in mediating estrogen signaling in the skeleton. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2014; 29:1206–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rajamannan N.M., Subramaniam M., Abraham T.P., Vasile V.C., Ackerman M.J., Monroe D.G., Chew T.L., Spelsberg T.C.. TGFbeta inducible early gene-1 (TIEG1) and cardiac hypertrophy: discovery and characterization of a novel signaling pathway. J. Cell Biochem. 2007; 100:315–325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rodriguez I. Drosophila TIEG is a modulator of different signalling pathways involved in wing patterning and cell proliferation. PLoS One. 2011; 6:e18418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Killick R., Ribe E.M., Al-Shawi R., Malik B., Hooper C., Fernandes C., Dobson R., Nolan P.M., Lourdusamy A., Furney S. et al. . Clusterin regulates beta-amyloid toxicity via Dickkopf-1-driven induction of the wnt-PCP-JNK pathway. Mol. Psychiatry. 2014; 19:88–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moriguchi M., Yamada M., Miake Y., Yanagisawa T.. Transforming growth factor beta inducible apoptotic cascade in epithelial cells during rat molar tooth eruptions. Anat. Sci. Int. 2010; 85:92–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Clevers H., Nusse R.. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012; 149:1192–1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gong Y., Slee R.B., Fukai N., Rawadi G., Roman-Roman S., Reginato A.M., Wang H., Cundy T., Glorieux F.H., Lev D. et al. . LDL receptor-related protein 5 (LRP5) affects bone accrual and eye development. Cell. 2001; 107:513–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boyden L.M., Mao J.H., Belsky J., Mitzner L., Farhi A., Mitnick M.A., Wu D.Q., Insogna K., Lifton R.P.. High bone density due to a mutation in LDL-receptor-related protein 5. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002; 346:1513–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Little R.D., Carulli J.P., Del Mastro R.G., Dupuis J., Osborne M., Folz C., Manning S.P., Swain P.M., Zhao S.C., Eustace B. et al. . A mutation in the LDL receptor-related protein 5 gene results in the autosomal dominant high-bone-mass trait. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002; 70:11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kato M., Patel M.S., Levasseur R., Lobov I., Chang B.H., Glass D.A. 2nd, Hartmann C., Li L., Hwang T.H., Brayton C.F. et al. . Cbfa1-independent decrease in osteoblast proliferation, osteopenia, and persistent embryonic eye vascularization in mice deficient in Lrp5, a Wnt coreceptor. J. Cell. Biol. 2002; 157:303–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Holmen S.L., Giambernardi T.A., Zylstra C.R., Buckner-Berghuis B.D., Resau J.H., Hess J.F., Glatt V., Bouxsein M.L., Ai M., Warman M.L. et al. . Decreased BMD and limb deformities in mice carrying mutations in both Lrp5 and Lrp6. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2004; 19:2033–2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Akhter M.P., Wells D.J., Short S.J., Cullen D.M., Johnson M.L., Haynatzki G.R., Babij P., Allen K.M., Yaworsky P.J., Bex F. et al. . Bone biomechanical properties in LRP5 mutant mice. Bone. 2004; 35:162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Glass D.A. 2nd, Bialek P., Ahn J.D., Starbuck M., Patel M.S., Clevers H., Taketo M.M., Long F., McMahon A.P., Lang R.A. et al. . Canonical Wnt signaling in differentiated osteoblasts controls osteoclast differentiation. Dev. Cell. 2005; 8:751–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Holmen S.L., Zylstra C.R., Mukherjee A., Sigler R.E., Faugere M.C., Bouxsein M.L., Deng L., Clemens T.L., Williams B.O.. Essential role of beta-catenin in postnatal bone acquisition. J. Biol. Chem. 2005; 280:21162–21168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kramer I., Halleux C., Keller H., Pegurri M., Gooi J.H., Weber P.B., Feng J.Q., Bonewald L.F., Kneissel M.. Osteocyte Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is required for normal bone homeostasis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010; 30:3071–3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. DasGupta R., Fuchs E.. Multiple roles for activated LEF/TCF transcription complexes during hair follicle development and differentiation. Development. 1999; 126:4557–4568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Edwards C.M., Edwards J.R., Lwin S.T., Esparza J., Oyajobi B.O., McCluskey B., Munoz S., Grubbs B., Mundy G.R.. Increasing Wnt signaling in the bone marrow microenvironment inhibits the development of myeloma bone disease and reduces tumor burden in bone in vivo. Blood. 2008; 111:2833–2842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peng D.J., Zeng M., Muromoto R., Matsuda T., Shimoda K., Subramaniam M., Spelsberg T.C., Wei W.Z., Venuprasad K.. Noncanonical K27-linked polyubiquitination of TIEG1 regulates Foxp3 expression and tumor growth. J. Immunol. 2011; 186:5638–5647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hens J.R., Wilson K.M., Dann P., Chen X., Horowitz M.C., Wysolmerski J.J.. TOPGAL mice show that the canonical Wnt signaling pathway is active during bone development and growth and is activated by mechanical loading in vitro. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2005; 20:1103–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Shao J.S., Cheng S.L., Pingsterhaus J.M., Charlton-Kachigian N., Loewy A.P., Towler D.A.. Msx2 promotes cardiovascular calcification by activating paracrine Wnt signals. J. Clin. Invest. 2005; 115:1210–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cheng S.L., Shao J.S., Cai J., Sierra O.L., Towler D.A.. Msx2 exerts bone anabolism via canonical Wnt signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2008; 283:20505–20522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang K., Barragan-Adjemian C., Ye L., Kotha S., Dallas M., Lu Y., Zhao S., Harris M., Harris S.E., Feng J.Q. et al. . E11/gp38 selective expression in osteocytes: regulation by mechanical strain and role in dendrite elongation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006; 26:4539–4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bottomly D., Kyler S.L., McWeeney S.K., Yochum G.S.. Identification of {beta}-catenin binding regions in colon cancer cells using ChIP-Seq. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010; 38:5735–5745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Han N., Zheng Y., Li R., Li X., Zhou M., Niu Y., Zhang Q.. beta-catenin enhances odontoblastic differentiation of dental pulp cells through activation of Runx2. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e88890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Brazil D.P., Yang Z.Z., Hemmings B.A.. Advances in protein kinase B signalling: AKTion on multiple fronts. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004; 29:233–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Armstrong V.J., Muzylak M., Sunters A., Zaman G., Saxon L.K., Price J.S., Lanyon L.E.. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is a component of osteoblastic bone cell early responses to load-bearing and requires estrogen receptor alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 2007; 282:20715–20727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gordon M.D., Nusse R.. Wnt signaling: multiple pathways, multiple receptors, and multiple transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem. 2006; 281:22429–22433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Moon R.T., Kohn A.D., De Ferrari G.V., Kaykas A.. WNT and beta-catenin signalling: diseases and therapies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004; 5:691–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rubinfeld B., Albert I., Porfiri E., Fiol C., Munemitsu S., Polakis P.. Binding of GSK3beta to the APC-beta-catenin complex and regulation of complex assembly. Science. 1996; 272:1023–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fukumoto S., Hsieh C.M., Maemura K., Layne M.D., Yet S.F., Lee K.H., Matsui T., Rosenzweig A., Taylor W.G., Rubin J.S. et al. . Akt participation in the Wnt signaling pathway through Dishevelled. J. Biol. Chem. 2001; 276:17479–17483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wandosell F., Varea O., Arevalo M.A., Garcia-Segura L.M.. Oestradiol regulates beta-catenin-mediated transcription in neurones. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2012; 24:191–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bhukhai K., Suksen K., Bhummaphan N., Janjorn K., Thongon N., Tantikanlayaporn D., Piyachaturawat P., Suksamrarn A., Chairoungdua A.. A phytoestrogen diarylheptanoid mediates estrogen receptor/Akt/glycogen synthase kinase 3beta protein-dependent activation of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2012; 287:36168–36178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Xia X., Batra N., Shi Q., Bonewald L.F., Sprague E., Jiang J.X.. Prostaglandin promotion of osteocyte gap junction function through transcriptional regulation of connexin 43 by glycogen synthase kinase 3/beta-catenin signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010; 30:206–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hajduch E., Heyes R.R., Watt P.W., Hundal H.S.. Lactate transport in rat adipocytes: identification of monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) and its modulation during streptozotocin-induced diabetes. FEBS Lett. 2000; 479:89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hedgepeth C.M., Conrad L.J., Zhang J., Huang H.C., Lee V.M., Klein P.S.. Activation of the Wnt signaling pathway: a molecular mechanism for lithium action. Dev. Biol. 1997; 185:82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Klein P.S., Melton D.A.. A molecular mechanism for the effect of lithium on development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996; 93:8455–8459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Behrens J., von Kries J.P., Kuhl M., Bruhn L., Wedlich D., Grosschedl R., Birchmeier W.. Functional interaction of beta-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature. 1996; 382:638–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Molenaar M., van de Wetering M., Oosterwegel M., Peterson-Maduro J., Godsave S., Korinek V., Roose J., Destree O., Clevers H.. XTcf-3 transcription factor mediates beta-catenin-induced axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell. 1996; 86:391–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Alemu E.A., Sjottem E., Outzen H., Larsen K.B., Holm T., Bjorkoy G., Johansen T.. Transforming growth factor-beta-inducible early response gene 1 is a novel substrate for atypical protein kinase Cs. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011; 68:1953–1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]