Abstract

Background

Treatment of older adults with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) using standard, intensive chemotherapy has been associated with poor outcomes. Effective, less toxic therapies are needed to achieve and maintain durable remissions.

Methods

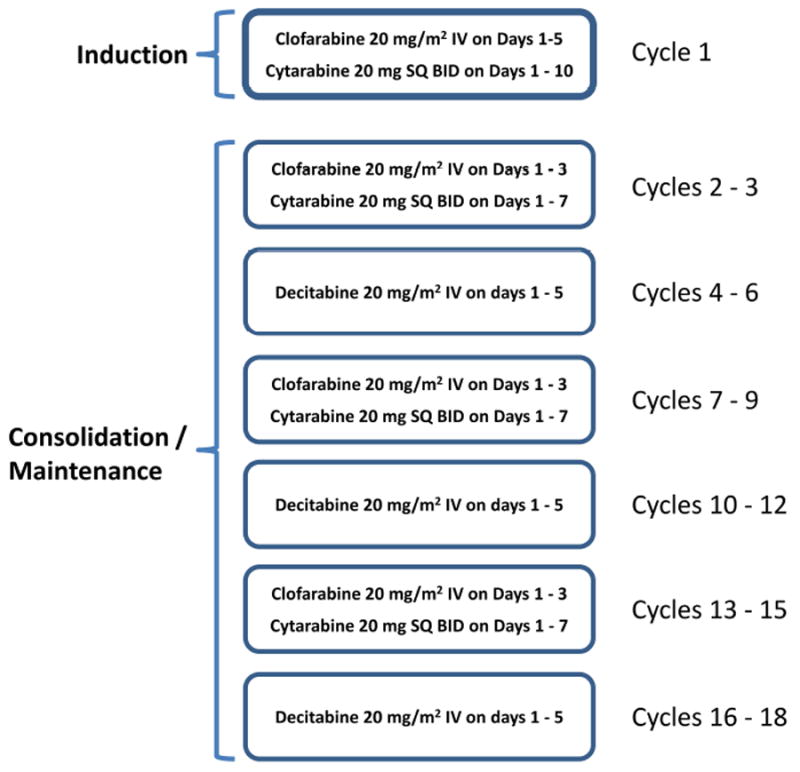

One-hundred eighteen patients with a median age of 68 years (range, 60-81) and newly diagnosed AML were treated with a regimen of clofarabine and low-dose cytarabine (LDAC) alternating with decitabine (DAC). Induction consisted of clofarabine 20mg/m2 IV on days 1-5 combined with LDAC 20 mg subcutaneously (SQ) twice daily on days 1-10. Responding patients were then treated with a prolonged consolidation / maintenance regimen consisting of cycles of clofarabine + LDAC alternating with cycles of DAC.

Results

The overall response rate was 68%. The complete remission (CR) rate was 60% overall, 71% in patients with a diploid karyotype and 50% in those with an adverse karyotype. The median overall survival (OS) was 11.1 months among all patients and 18.5 months in those achieving a CR/CR with incomplete platelet recovery (CRp). The median relapse-free survival (RFS) for patients achieving a CR/CRp was 14.1 months. By multivariate analysis, only adverse cytogenetics and WBC ≥10 predicted for worse OS. The regimen was well tolerated, with 4- and 8-week mortality rates of 3% and 7%, respectively. The most common non-hematologic adverse events were nausea, elevated liver enzymes, and rash.

Conclusion

The lower-intensity, prolonged-therapy program of clofarabine and LDAC alternating with DAC is well tolerated and highly effective in older patients with AML.

Keywords: Elderly AML, maintenance, low intensity

INTRODUCTION

Although intensive chemotherapy with anthracyclines and higher doses of cytarabine (araC) are considered standard treatment for most younger patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a significant proportion of patients over age 60 years may not benefit from this approach.1, 2 Along with higher rates of comorbidities and organ dysfunction in older patients, AML in this population is associated with adverse features, lower rates of complete remission (CR), shorter durations of CR, and higher early mortality. Since most patients with AML are > 60 years, developing safer, effective regimens is a priority.

Clofarabine is a purine nucleoside analogue that is approved for the treatment of relapsed or refractory pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia after at least 2 prior regimens, but has demonstrated activity in AML. An initial phase I dose-escalation study of single-agent clofarabine determined the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) in leukemia to be 40 mg/m2 × 5 days with hepatotoxicity being the dose-limiting toxicity.3 Subsequent studies have shown lower doses to be safe and effective in patients with AML.4, 5 Based on further studies confirming the activity of clofarabine in AML, and the finding of synergy in combination with araC, clofarabine was successfully combined with varying doses of araC in relapsed and previously untreated patients.6-9 In a randomized study of clofarabine with or without low-dose araC (LDAC) in older (≥ 60 years) patients with newly diagnosed AML, we previously demonstrated a favorable safety profile and an improved CR rate (63% vs. 31%, p=0.025) for the combination.7 However, there was no significant difference in overall survival (OS).

This lack of OS benefit despite reducing early mortality and achieving higher rates of CR highlights the importance of maintaining remissions with prolonged, lower-intensity therapy, particularly in patients who are not candidates for allogeneic stem cell transplantation. To build on our prior experience with clofarabine + LDAC and to improve postremisson consolidation strategy, a prolonged, alternating combination of clofarabine + LDAC alternating with decitabine was developed. In our initial experience of 59 patients ≥ 60 years treated with this regimen, we observed a CR rate of 58% and improved median relapse-free survival (RFS) of 14.1 months compared to historical controls.10 Here we report on the final results of this phase II trial with mature follow-up.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Eligibility Criteria

This open-label, prospective phase II study (Protocol 2007-0039) was approved by the Institutional Review Board of MD Anderson Cancer Center, and all patients provided written informed consent according to institutional guidelines. The study was conducted in concordance with the declaration of Helsinki.

Patients ≥ 60 years of age and ECOG performance status ≤ 2, with previously untreated AML (non-M3) and high-risk (≥ 10% marrow blasts or ≥ IPSS intermediate-2 risk) myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) were eligible for enrollment. Other eligibility criteria included adequate hepatic (serum bilirubin ≤ 1.5 × upper limit of normal [ULN]; ALT and/or AST ≤ 2.5 × ULN) and renal (creatinine ≤ 1.5 mg/dL) functions, and the ability to sign informed consent. Pregnant patients and those with an ejection fraction < 40% were excluded. Patients with prior exposure to clofarabine or decitabine were also not eligible.

Treatment plan

The treatment plan consisted of a rotating schedule of 3 cycles of clofarabine + LDAC (cycle A) alternating with 3 cycles of decitabine (cycle B) for up to 18 cycles as previously described (Figure 1).10 A treatment cycle was defined as a minimum of 28 days. Induction therapy (cycle 1) consisted of clofarabine 20 mg/m2 intravenously (IV) over 1 – 2 hours on Days 1 to 5 and cytarabine 20 mg subcutaneously (SQ) twice daily (BID) on days 1 – 10. On the days of combination treatment (ie. days 1-5 in induction and days 1-3 of consolidation cycle A) cytarabine was administered 3 – 6 hours following the start of the clofarabine infusions to take advantage of their pharmacodynamic interaction. Patients could receive up to 2 cycles of induction chemotherapy if complete remission (CR) was not achieved after cycle 1. Patients achieving a remission could then move onto consolidation therapy, which consisted of clofarabine 20 mg/m2 IV over 1 – 2 hours on Days 1 to 3 and cytarabine 20 mg SQ BID on days 1 – 7 (cycle A), alternating with decitabine 20 mg/m2 IV on days 1 – 5 (cycle B) as described above. Patients could receive up to a total of 17 consolidation cycles, which could be given every 4 to 7 weeks depending on adequate blood count recovery (absolute neutrophil count [ANC] ≥ 1 × 109/L and platelet count ≥ 50 × 109/L) and resolution of non-hematologic toxicities to ≤ grade 1. Dose interruptions and dose modifications were implemented for grade 3 or higher non-hematologic toxicity and missed doses were not made up.

Figure 1.

Overall study schema describing induction, followed by alternating consolidation cycles.

Supportive care was continued in all patients per institutional guidelines. Myeloid growth factors (G-CSF or GM-CSF) were permitted, if in the best interest of the patient. Prophylactic broad spectrum antibiotics were permitted, and all patients received levofloxacin, fluconazole, and valacyclovir (or their equivalent) while on study. When possible, use of nephrotoxic and hepatotoxic agents were strongly discouraged and to be avoided during the clofarabine administration during all cycles.

Response Criteria

A CR was defined as normalization of peripheral blood and bone marrow (BM) with < 5% blasts, a peripheral absolute neutrophil count (ANC) ≥ 1 × 109/L, and a platelet count ≥ 100 × 109/L. A partial response (PR) was defined as the same blood count recovery as CR with a decrease in BM blasts of at least 50% and not more than 6-25% of abnormal cells in the BM. CRp was defined the same as CR, but without recovery of platelet count ≥ 100 × 109/L.

Statistical Analysis

The primary objective of this phase 2 trial was to determine RFS and overall survival (OS). Relapse-free survival (RFS) was defined as the interval from the time of first response (CR or CRp) until the date of relapse or death, whichever occurred first. CR or CRp patients who were alive and relapse-free were censored at the off-study date. Overall survival (OS) was measured from the time of initiation on study until death. Interim stopping boundaries were developed for monitoring efficacy and safety.

Patient characteristics were summarized using frequency (percentage) for categorical variables and median (range) for continuous variables. Fisher exact test was used to assess the differences in categorical variables between patients in various subgroups. Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare continuous variables. OS and RFS were estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier. Log-rank test was used to compare OS or RFS between subgroups of patients. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were fit to assess the association between OS or RFS and patient prognostic factors. Safety data was summarized by category, severity and frequency. All statistical analyses were performed using Statistica, SAS, and Splus.12

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

A total of 118 patients aged ≥ 60 years, with newly diagnosed AML were treated on the protocol, with a median follow-up of 41.4 months. The patients’ baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Their median age was 68 years (range, 60-81), and 46 patients (39%) were 70 years of age or older. Over half the patients (54%) had an antecedent hematologic disorder (AHD) prior to their diagnosis of AML and 15 patients (13%) received therapy for their AHD prior to enrolling on the current trial. Thirty-six patients (31%) had received prior chemotherapy or radiation for a previous (non-myeloid) malignancy and were considered to have therapy-related AML (t-AML). Pretreatment karyotype evaluation revealed 45 patients (38%) with a normal or diploid karyotype, 42 (36%) patients with abnormalities of chromosomes 5 and/or 7, and 25 (21%) with other abnormalities. Thirty-eight patients (32%) had a complex karyotype, defined has have 3 or more chromosomal abnormalities. Overall 41% of patients were categorized as having and adverse-risk karyotype. Seven patients (7%) had pretreatment FLT3 mutations, and 11 patients (12%) had NPM1 mutations.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | All Patients |

|---|---|

| (N = 118) | |

| Median age, years (range) | 68 (60 - 81) |

| Age ≥ 70 years, N (%) | 46 (39) |

| Female sex, N (%) | 43 (36) |

| ECOG Performance Status 2, N (%) | 15 (13) |

| Patients with Prior AHD, N (%) | 64 (54) |

| Patients Prior Rx for AHD, N (%) | 15 (13) |

| Patients with Prior Chemo/XRT, N (%) | 36 (31) |

| Cytogenetics | |

| Diploid | 45 (38) |

| -5/5q- and/or -7/7q- | 42 (36) |

| Other | 25 (21) |

| Complex karyotype (≥ 3 abnl) | 38 (32) |

| Insufficient metaphases / Not done | 6 (5) |

| FLT3 Positive, N (%) | 7/101 (7) |

| NPM1 Positive, N (%) | 11/91 (12) |

| Median WBC [× 109/L] (range) | 2.7 (0.4 - 186.5) |

| Median Hb [g/L] (range) | 9.3 (6.7 - 13.5) |

| Median Platelets [× 109/L] (range) | 45 (6 - 416) |

| % PB Blasts, median (range) | 9 (0 - 98) |

| % Marrow Blasts, median (range) | 37 (4 - 95) |

N: number of patients; AHD: antecedent hematologic disorder; Rx: therapy; Chemo: chemotherapy; XRT: radiotherapy; abnl: abnormalities; WBC: white blood cell; PB: peripheral blood; Hb: hemoglobin;

Efficacy

A summary of responses overall and by patient subgroups are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Patients received a median of 3 cycles of therapy (range 1-19). Among the 118 evaluable patients, 71 (60%) achieved CR, 8 (7%) achieved CRp, and 1 (1%) patient had a PR, for a CR/CRp rate of 67% and an overall response rate (ORR, CR+CRp+PR) of 68%. Patients needed a median of 1 cycle to achieve a response (range, 1-6). When analyzed by subgroup, patients between the ages of 60 and 69 years had a similar rate of CR compared to those aged 70 years or older. However, patients with diploid karyotype had a higher rate of CR (71%), compared to those with adverse karyotype (50%) (p=0.05), those with prior AHD (55%)(p=0.11), and particularly those treated for a prior AHD (33%)(p=0.01). Sixteen patients (14%) proceeded to stem cell transplant (SCT).

Table 2.

Outcomes (N = 118)

| Response / Outcome | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| CR | 71 | 60 |

| CRp | 8 | 7 |

| PR | 1 | 1 |

| ORR (CR + CRp + PR) | 80 | 68 |

| Early death (≤ 4 weeks) | 4 | 3 |

| Median No. of cycles given (range) | 3 (1 - 19) | |

| Median No. of cycles to response [CR, CRp] (range) | 1 (1 - 6) | |

N: number of patients; CR: complete remission; CRp: CR with incomplete platelet recovery; PR: partial remission; ORR: overall response rate, equals CR+CRp+PR; No: number;

Table 3.

Response by Patient Subgroup (N = 118)

| Characteristic | N | No. CR (%) | No. CRp (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 60 - 69 years | 72 | 44 (61) | 4 (6) |

| ≥ 70 years | 46 | 27 (59) | 4 (5) |

| Karyotype | |||

| Diploid | 45 | 32 (71) | 4 (9) |

| -5/5q- and/or -7/7q- | 42 | 21 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Complex | 38 | 19 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Prior AHD | 64 | 35 (55) | 6 (9) |

| Pts. Treated for Prior AHD | 15 | 5 (33) | 2 (13) |

N: number of patients (Pts); No.: Number of responding patients; CR: complete remission; CRp: CR without platelet recovery; Diploid: normal diploid karyotype; complex: complex karyotype, defined as > 2 chromosomal abnormalities; AHD: antecedent hematologic disorder.

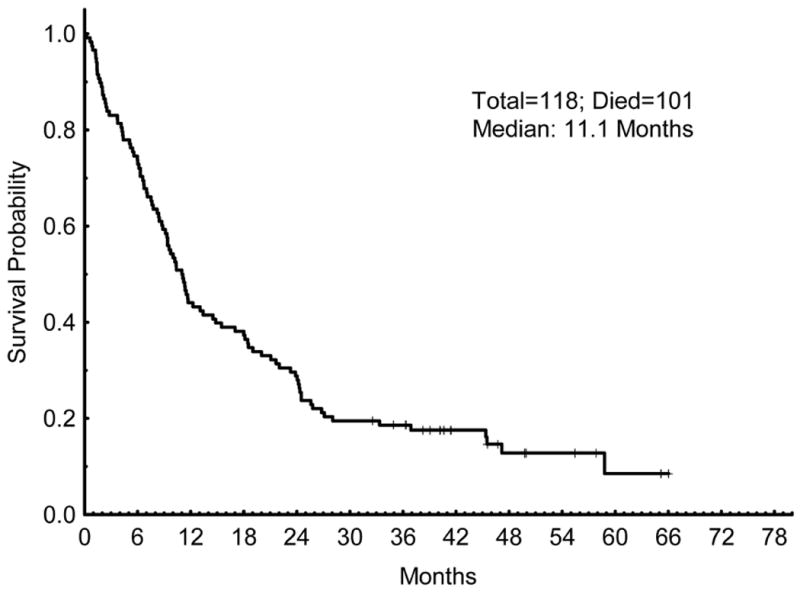

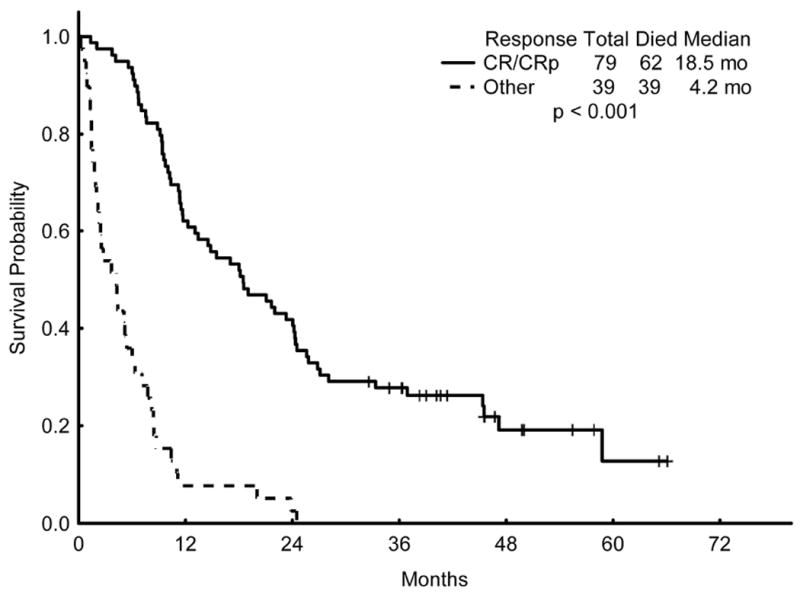

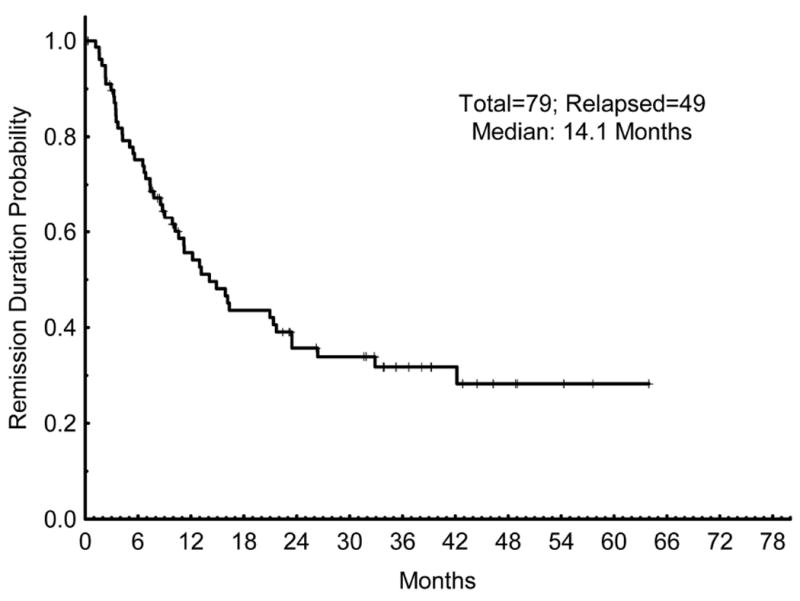

The median overall survival for all patients was 11.1 months (Figure 2). The median OS for responding patients (CR/CRp) was 18.5 months, compared to 4.2 months for patients not achieving a CR/CRp (p < 0.001) (Figure 3). The median relapse-free survival (RFS) for all patients achieving a CR/CRp was 14.1 months (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Overall Survival (OS). OS for all patients that were treated on the trial.

Figure 3.

Overall Survival (OS) of patients who achieved a complete remission (CR) or CR with incomplete platelet recovery (CRp) compared to the OS of those who did not achieve CR/CRp.

Figure 4.

Remission duration (CRd). CRd for all patients who achieved a response (CR or CRp).

We performed a multivariate analysis to determine whether specific baseline characteristics predicted for OS. A univariate analysis for OS was first conducted to determine which pretreatment characteristics met the threshold of significance to be entered into the multivariable model (Table 4). We included all factors with a p-value ≤ 0.1 from the univariate analysis into the multivariate model, including performance status (p=0.03), history of therapy for prior AHD (p=0.04), t-AML (p=0.007), cytogenetics [diploid vs. adverse] (p <0.0001), and WBC count (p=0.1). By multivariate analysis, the only 2 factors that significantly predicted for inferior OS were WBC ≥ 10 (p=0.02) and adverse karyotype (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate analysis for Overall Survival

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Parameter | p-value | Characteristic | p-value |

| Age (y) | 60 - 69 | 0.976 | ||

| ≥ 70 | ||||

| ECOG PS | 0 - 1 | 0.027 | ECOG PS | 0.068 |

| 2 | ||||

| Prior AHD | No vs. Yes | 0.379 | ||

| Rx. for prior AHD | No vs. Yes | 0.037 | Rx. for prior AHD | 0.202 |

| Therapy-related AML | No vs. Yes | 0.007 | Therapy-related AML | 0.383 |

| Cytogenetics | Diploid vs. Adverse | < 0.0001 | Cytogenetics (Diploid vs. Adverse) | <0.001 |

| Diploid vs. -5/-7 | < 0.0001 | |||

| Not complex vs. Complex | < 0.0001 | |||

| WBC [× 109/L] | 0 - 9 | 0.099 | WBC [× 109/L] | 0.024 |

| ≥ 10 | ||||

| BM Blast (%) | 20 - 29 | 0.507 | ||

| ≥ 30 | ||||

| LDH (IU/L) | < 1000 | 0.39 | ||

| ≥ 1000 | ||||

y: years; PS: performance status; AHD: antecedent hematologic disorder; Rx.: therapy; AML: acute myeloid leukemia; WBC: white blood cell count; BM: bone marrow; LDG: lactate dehydrogenase; IU: international units; L: liter.

Safety and Tolerability

All patients who received any therapy were eligible for toxicity evaluation. Given the patient-population enrolled and treatment regimen, myelosuppression occurred in all patients. Non-hematologic, possibly-related adverse events are outlined by frequency and grade in Table 5. The regimen was well tolerated in this older population with a 4-week mortality rate of only 3%. Most patients received the first cycle (induction) as an inpatient in a negative air-pressure laminar flow room on the leukemia floor. Grade 3 and 4 infections were common in this population. Febrile neutropenia occurred in 61% of patients and grade 3 or 4 infection was documented in 41%. Other than these, the most common non-hematologic toxicities were nausea (81%), elevated liver transaminases (64%), rash (56%), elevated bilirubin (47%), nonspecific pain (32%), diarrhea (19%), and elevated creatinine (13%). The most common grade 3 or 4 non hematologic toxicities were elevated transaminases (11%), elevated bilirubin (5%), elevated creatinine (3%), and rash (2%). Elevations in liver function tests (AST/ALT, bilirubin) were mostly transient and responded to interruptions or delays in therapy

Table 5.

Possibly Related Non-Hematologic Toxicities (N = 118)

| Toxicity | All grades | Grade 3/4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Nausea | 95 | 81 | 0 | 0 |

| Elevated AST/ALT | 75 | 64 | 13 | 11 |

| Febrile neutropenia | 72 | 61 | 72 | 61 |

| Rash/desquamation | 66 | 56 | 2 | 2 |

| Elevated Bilirubin | 56 | 47 | 6 | 5 |

| Infection-other | 48 | 41 | 48 | 41 |

| Pain | 38 | 32 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 22 | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| Elevated Creatinine | 15 | 13 | 3 | 3 |

| Rash: hand-foot syndrome | 13 | 11 | 1 | 1 |

| Constipation | 7 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Pruritus | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Mucositis / stomatitis | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Neuropathy | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Elevated Amylase/Lipase | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Allergic Reaction | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cardiac Arrhythmia-Other | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Coagulation-Other | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Edema: larynx | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Edema: trunk/general | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Flushing | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Insomnia | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Altered mental status | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Muscle weakness | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Syncope | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Patients came off of therapy for the following reasons: 34% came off due to refractory disease/ inadequate response, 27% came off for relapse, 14% of patients went to allogeneic SCT, 12% completed all therapy and/or changed to a different therapy, 8% came of due to patient or physician choice, 3% came off for infection or toxicity, and 1% each came off study due to development of extramedullary disease, death in CR, and prolonged myelosuppression.

DISCUSSION

Most patients with AML are older than 60 years of age. The challenge in treating AML in older adults is offering highly effective therapy, that has low rates of toxicity, and which translates improved remission rates into improved survival. Due to lower expected rates of complete remission and higher likelihood of increased toxicity, older patients with AML may not benefit from intensive chemotherapy. We previously evaluated the outcomes of AML patients >65 years1 and > 70 years2 treated with intensive chemotherapy at MD Anderson Cancer Center. In this population, we reported a CR rate of 45% and median OS of 4.6 months. The rates of induction mortality at 4-weeks and 8-weeks were 26% and 36%, respectively. With the exception of fit older patients with favorable karyotype and preserved organ function, we concluded that most older patients with AML would not benefit from intensive chemotherapy approaches.

The current study with clofarabine and LDAC alternating with decitabine offers a lower-intensity approach that demonstrates a CR/CRp rate 67% with 4-week and 8-week mortality rates 3% and 7%, respectively in a cohort of patients with a median age of 68 years and several adverse risk factors. Over half the patients had prior AHD, 31% had t-AML, and 32% had a complex karyotype. This therapy translated into a median OS of 11.1 months in the whole cohort, 18.5 months in responding patients, and a RFS of 14.1 months. The significance of these data can be examined in the context of other lower intensity treatment approaches for older patients with newly diagnosed AML.

Hypomethylating agents such as 5-azacytidine (5-AZA) and decitabine (DAC) which were developed for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes are regularly applied as lower intensity therapy in older patients with AML. The activity of 5-AZA was observed in a post-hoc subset analysis of a randomized phase III trial of 5-AZA vs. conventional care treatment (CC) in patients with high-risk MDS.11 In the subset of 113 patients (median age 70) with 20-30% blasts, classified as AML by the WHO, 5-AZA resulted in a response rate of 18% and significant improvement in median OS compared with CC (24.5 vs. 16 months, p=0.001).11 Subsequent single-arm studies of 5-AZA have confirmed its activity in older patients with AML.12-14 In patients with median ages ranging from 72 to 74 years, these studies have reported response rates of 33% to 50% and median OS of 3 to 9.4 months.12-14 Notably, none have reproduced the OS observed in the MDS study. This important difference is likely related to differences in patient characteristics and in particular the lower median bone marrow (BM) blast percentage in those patients on the MDS trial (20-30%). Indeed, the median BM blast percentage of patients in these trials ranged from 33% to 42%. The AML-001 trial was designed to address this question of the efficacy of 5-AZA in older patients with AML and BM blasts ≥ 30%. Dombret et. al. recently presented preliminary results from this phase III study.15 Similar to the MDS trial, 488 patients (median age 75 years) with AML and BM blasts ≥ 30% were randomized to either 5-AZA or CC. The ORR was 28% for 5-AZA vs. 25% for CC, leading to trend towards improved median OS for patients treated with 5-AZA (10.4 vs. 6.5 months, p=0.08).15 Patients on the current of study of clofarabine and LDAC had median BM blasts of 37%, with 77 (65%) patients having BM blast ≥ 30%, with outcomes comparing favorably to this data.

DAC has been similarly studied in several single-arm studies. In patients with median ages of 72 to 74 years, and median BM blasts of 50% to 56%, DAC was associated with ORR’s of 25% to 26% and median OS of 5.5 to 7.7 months.16, 17 DAC was also studied in a phase III randomized trial compared to treatment choice (TC) in 485 older patients (median age 73 years) with AML and a median BM blast count of 46%.18 In this trial DAC produced a response rate of 17.8% vs. 7.8% for TC, translating into an improved OS of 7.7 vs. 5 months (p=0.037).18 In an effort to further improve response rates several groups have studied a 10-day schedule of DAC instead of the 5-day regimen. Blum et. al. reported an ORR of 64% and a median OS of 55 weeks in 53 patients with a median age of 74 years, of whom 25% had prior AHD, 11% had t-AML, and 30% had complex karyotype.19 The 4- and 8-week mortality rates were 2% and 15%, respectively.19 Ritchie et. al. used a 10-day schedule of DAC in 52 patients with a median age of 74 years and reported a CR rate of 40% with a median OS of 10.6 months overall and 16 months in responders.20

One of the major goals of our lower intensity approach in a population of patients who were not ideal candidates for allogeneic SCT was to reduce the risk of relapse. The prolonged consolidation / maintenance therapy was designed with alternating cycles of different chemotherapy drugs to try and address this challenge. First, we hypothesized that alternating 3 cycles of clofarabine/LDAC with 3 cycles of DAC would reduce the development of resistance and thereby prolong the duration of remission. Second, we recognized the differences in intensity and side-effect profile between cycle A and cycle B. In order to deliver up to 18 months of chemotherapy, the alternating cycles would mitigate cumulative toxicities and preserve longer-term tolerance of the regimen. Indeed, this alternating program achieved a median RFS of 14.1 months, with a median follow-up of 41.4 months, and compares very favorably to data from previous trials of hypomethylating agents in this setting.

Although we can examine the response rates, survival, and CR durations across trials and even try to match patient characteristics to compare similar groups, one of the major limitations of our study is that it is a single-arm phase II without a comparator arm. While an earlier report of this trial compared outcomes to historical controls, a randomized trial in older patients with AML comparing the current regimen with a ‘standard’ lower intensity approach would be needed to confirm the advantage of this regimen. The large cohort size and long follow-up allowed us to examine the impact of baseline patient characteristics on OS. Advanced performance status, treatment for prior AHD, the diagnosis of t-AML, adverse karyotype, and elevated WBC count were significant negative prognostic factors in the univariate analysis. But only adverse cytogenetics, and WBC ≥ 10 were significant in the multivariate analysis, with performance status having marginal significance.

The regimen was well tolerated. As would be expected, all patients experienced myelosuppression. In some patients, prolonged myelosuppression with repeated cycles was managed with dose delays and dose-reductions. Despite antimicrobial prophylaxis, febrile neutropenia and documented infections in the setting of neutropenia were common, occurring in 61% and 41%, respectively. However, these patients were treated with broad spectrum IV antibiotics and growth factors when appropriate, leading to a low rate of death due to infection. Elevations in liver transaminases and bilirubin were also commonly seen, particularly during the clofarabine-based cycles. However, the elevations were usually transient, temporally related to drug infusion, and not clinically significant. Care was taken to avoid the concomitant use of hepatotoxic medications such as antifungal azoles during clofarabine therapy and serum chemistries were monitored closely to document improvement. Rash, including hand-foot syndrome occurred in over two-thirds of patients at varying levels of severity and was also related to clofarabine. Supportive care, including topical moisturizing ointments and low-dose topical steroids were used regularly preventatively and in response to worsening rash. These measures kept the skin toxicity self-limiting, except for the rare cases which required therapy delay or dose-reduction. The lower intensity approach of this regimen is exemplified by the low early death rate at 4- and 8-weeks of 3% and 7%, respectively despite a CR rate of 60%, a 2-year OS rate of 29%, and a 2-year RFS rate of 36%. For comparison, a higher intensity, high-dose daunorubicin-based approach demonstrated a CR rate of 64%, comparable rates of 2-year OS and 2-year DFS of 31% and 30%, respectively but at the cost of a 30-day mortality rate of 11%.21

In conclusion, the combination of clofarabine and LDAC alternating with DAC implemented in a prolonged consolidation / maintenance program is well tolerated and highly effective in older patients with AML. Further studies expanding on this strategy and prospectively comparing it to existing higher and lower intensity therapies in older adults are needed.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by research funding from Genzyme, Inc., Eisai, Inc., and in part by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson’s Cancer Center support grant CA016672.

Footnotes

AUTHORSHIP

TMK, SF, FR and HK coordinated the study and performed the research. TMK, SF, XH, XW, MB, JF, and SP collected, analyzed, and interpreted the data. TMK, SF, FR, EJ, GGM, GB, AF, MK, JB, JC, and HK contributed patients for the study. TMK, SF, FR and HK wrote the manuscript with input from EJ, GGM, GB, AF, MK, JB, XH, XW, SP, MB, and JC. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: SF has received research funding from Genzyme, Inc. and Eisai, Inc.

References

- 1.Kantarjian H, O’Brien S, Cortes J, et al. Results of intensive chemotherapy in 998 patients age 65 years or older with acute myeloid leukemia or high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome: predictive prognostic models for outcome. Cancer. 2006;106(5):1090–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kantarjian H, Ravandi F, O’Brien S, et al. Intensive chemotherapy does not benefit most older patients (age 70 years or older) with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2010;116(22):4422–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kantarjian HM, Gandhi V, Kozuch P, et al. Phase I clinical and pharmacology study of clofarabine in patients with solid and hematologic cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(6):1167–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faderl S, Garcia-Manero G, Jabbour E, et al. A randomized study of 2 dose levels of intravenous clofarabine in the treatment of patients with higher-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer. 2012;118(3):722–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kantarjian HM, Erba HP, Claxton D, et al. Phase II study of clofarabine monotherapy in previously untreated older adults with acute myeloid leukemia and unfavorable prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(4):549–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.3130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faderl S, Gandhi V, O’Brien S, et al. Results of a phase 1-2 study of clofarabine in combination with cytarabine (ara-C) in relapsed and refractory acute leukemias. Blood. 2005;105(3):940–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Faderl S, Ravandi F, Huang X, et al. A randomized study of clofarabine versus clofarabine plus low-dose cytarabine as front-line therapy for patients aged 60 years and older with acute myeloid leukemia and high-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2008;112(5):1638–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-124602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faderl S, Verstovsek S, Cortes J, et al. Clofarabine and cytarabine combination as induction therapy for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in patients 50 years of age or older. Blood. 2006;108(1):45–51. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faderl S, Wetzler M, Rizzieri D, et al. Clofarabine plus cytarabine compared with cytarabine alone in older patients with relapsed or refractory acute myelogenous leukemia: results from the CLASSIC I Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(20):2492–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.9743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faderl S, Ravandi F, Huang X, et al. Clofarabine plus low-dose cytarabine followed by clofarabine plus low-dose cytarabine alternating with decitabine in acute myeloid leukemia frontline therapy for older patients. Cancer. 2012;118(18):4471–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fenaux P, Mufti GJ, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, et al. Azacitidine prolongs overall survival compared with conventional care regimens in elderly patients with low bone marrow blast count acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(4):562–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.8329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Ali HK, Jaekel N, Junghanss C, et al. Azacitidine in patients with acute myeloid leukemia medically unfit for or resistant to chemotherapy: a multicenter phase I/II study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53(1):110–7. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.606382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maurillo L, Venditti A, Spagnoli A, et al. Azacitidine for the treatment of patients with acute myeloid leukemia: report of 82 patients enrolled in an Italian Compassionate Program. Cancer. 2012;118(4):1014–22. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thepot S, Itzykson R, Seegers V, et al. Azacitidine in untreated acute myeloid leukemia: a report on 149 patients. Am J Hematol. 2014;89(4):410–6. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dombret H. Results of a Phase 3, Multicenter, Randomized, Open-Label Study of Azacytidine Versus Conventional Care Regimens in Olders Patients with Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia. EHA Annual Meeting Abstracts: LB-6212. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cashen AF, Schiller GJ, O’Donnell MR, DiPersio JF. Multicenter, phase II study of decitabine for the first-line treatment of older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(4):556–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lubbert M, Ruter BH, Claus R, et al. A multicenter phase II trial of decitabine as first-line treatment for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia judged unfit for induction chemotherapy. Haematologica. 2012;97(3):393–401. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.048231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kantarjian HM, Thomas XG, Dmoszynska A, et al. Multicenter, randomized, open-label, phase III trial of decitabine versus patient choice, with physician advice, of either supportive care or low-dose cytarabine for the treatment of older patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):2670–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.9429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blum W, Garzon R, Klisovic RB, et al. Clinical response and miR-29b predictive significance in older AML patients treated with a 10-day schedule of decitabine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(16):7473–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002650107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ritchie EK, Feldman EJ, Christos PJ, et al. Decitabine in patients with newly diagnosed and relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2013;54(9):2003–7. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.762093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowenberg B, Ossenkoppele GJ, van Putten W, et al. High-dose daunorubicin in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(13):1235–48. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]