Abstract

Background

Little is known about marijuana advertising exposure among users in the U.S. We examined the prevalence of advertising exposure among young adult marijuana users through traditional and new media, and identified characteristics associated with seeking advertisements.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of 18–34 year-old past-month marijuana users in the U.S. using a pre-existing online panel (N=742). The survey queried about passively viewing and actively seeking marijuana advertisements in the past month, sources of advertisements, and marijuana use characteristics.

Results

Over half of participants were exposed to marijuana advertising in the past month (28% passively observed advertisements, 26% actively sought advertisements). Common sources for observing advertisements were digital media (i.e., social media, online, text/emails; 77%). Similarly, those actively seeking advertisements often used Internet search engines (65%) and social media (53%). Seeking advertisements was more common among those who used medically (41% medical only, 36% medical and recreational) than recreational users (18%), who used concentrates or edibles (44% and 43%) compared to those who did not (20% and 19%), and who used multiple times per day (33%) compared to those who did not (19%) (all p<0.01).

Conclusions

Exposure to marijuana advertising among users is common, especially via digital media, and is associated with medical use, heavier use, and use of novel products with higher THC concentrations (i.e., concentrates) or longer intoxication duration (i.e., edibles). As the U.S. marijuana policy landscape changes, it will be important to examine potential causal associations between advertising exposure and continuation or frequency/quantity of use.

Keywords: marijuana, advertising, internet, social media

1. Introduction

In recent years, the legalization of medical and/or recreational marijuana has rapidly spread across the U.S. Currently, over half of states in the U.S. allow the use of marijuana for medical purposes, and eight of these states have also legalized the recreational use of marijuana (Marijuana Policy Project, n.d.). More states are expected to follow suit given that the percentage of Americans who favor marijuana legalization is the highest it has ever been (Stebbins and Comen, 2016; Pew Research Center, 2014; Jones, 2015). As a result, the marijuana industry has become one of the fastest growing industries in the U.S., with the legal marijuana market projected to be over $7 billion in 2016 (ArcView Market Research, 2015; Sola, 2016).

As the legal marijuana industry continues to grow, so will the commercial advertising of these products. While some state regulatory agencies have implemented restrictions on marijuana advertising, these regulations vary across states. For instance, some states prohibit advertising via specific media; for example, Delaware and Oregon prohibit advertisements in specific print or broadcast media. External signage and/or outdoor advertisements are also restricted in some states (Colorado, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Washington). False or misleading advertisements are banned in certain states (Colorado, Connecticut, New York, and Washington). Specific regulations to limit minors’ exposure to advertisements are also addressed in some state policies. For example, Illinois and Washington ban billboards within 1,000 feet of schools/playgrounds, several states ban the use of imagery portraying people under the legal age of consumption (Connecticut, Massachusetts, New York, Washington), Colorado and Washington ban the use of cartoon characters, and Colorado bans advertising on print, radio, and television when more than 30% of the audience is under the legal age. Online marijuana advertisements are also regulated by some states. Colorado bans online ads when more than 30% of the audience is expected to be under 21 years old and prohibits pop-up ads. Montana prohibits advertising in any medium and specifically states that this includes electronic media. Notably, several states still have no advertising regulations of any type in place (e.g., Arizona, Michigan, Minnesota, New Mexico, Rhode Island, Vermont) (Leafly, n.d.).

While it is well known that advertisements influence youth and young adults’ attitudes about, initiation of, and continued or increased use of alcohol and tobacco use (Anderson et al., 2009; Choi et al., 2002; Davis et al., 2008; Evans et al., 1995; Gilpin et al., 2007; Gordon et al., 2010; Lovato et al., 2003; Smith and Foxcroft, 2009), few studies have examined exposure to marijuana advertising and/or the content of such advertisements. A study in Southern California reported that up to 30% of middle school age participants had seen a medical marijuana advertisement in the past 3 months (either in billboards, magazines, or via other sources), and there was a reciprocal cross-lagged association between this exposure and marijuana use or intentions to use in the future (D’Amico et al., 2015). Because online advertising is an increasingly important medium for advertising in the U.S. and can be used by the marijuana industry to advertise dispensaries and products (eMarketer, 2016a), we recently studied marijuana advertising practices on Weedmaps, an online directory of marijuana dispensaries (Bierut et al., 2016). Our findings indicated that many dispensaries advertised health claims of the benefits of using marijuana, some of which have not yet been scientifically substantiated. Of particular note in relation to youth, many dispensaries lacked website restrictions to verify a person’s age before entering the dispensary’s own website.

Similar to tobacco and alcohol advertisements, commercial advertisements for marijuana have the potential to influence marijuana perceptions and use. Furthermore, restrictions on marijuana advertising across states are inconsistent and sometimes nonexistent. Due to the dearth of studies examining marijuana advertising in the U.S., we have taken the first steps to explore the prevalence of exposure to marijuana advertisements among marijuana users across the country. Using an existing online panel of respondents, we surveyed young adult marijuana users across the U.S. about their exposures to marijuana advertisements. We aimed to determine the prevalence of marijuana users who recently viewed and sought marijuana advertisements and to determine the sources of these advertisements, including traditional media sources such as print media, radio, and television as well as new digital media sources, including online and social media platforms. We also identified demographic and marijuana use characteristics associated with viewing and seeking marijuana advertisements.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Participants

Between June and September of 2015, we conducted an online survey with members of SurveyMonkey® Audience, a proprietary panel of participants drawn from the over 30 million people who take SurveyMonkey surveys. To recruit for this voluntary online panel, SurveyMonkey asks people who complete SurveyMonkey surveys whether they would like to be a member of the online panel. In exchange for being on the panel and taking surveys, the participant receives donations to charities or sweepstakes entries. When registering for the Audience panel, SurveyMonkey collects and stores detailed background information for each Audience member. SurveyMonkey limits the number of surveys each panel member can take per week and uses non-cash incentives to help maintain panelists who would provide high quality responses. Recent reliability tests of the U.S. SurveyMonkey Audience, which involved surveying panelists with the same survey for one week in each of three consecutive months, found that 85% of questions regarding personal or demographic characteristics, credit/debit card ownership/use, and internet use did not significantly differ across the three survey administrations (Wronski and Liu, 2016). Furthermore, benchmarking surveys are run regularly so that SurveyMonkey can ensure that the demographic characteristics of their Audience members are similar to the U.S. population; however, the sample is not nationally representative so we used weighting techniques described below.

The target sample size for our survey was approximately 3,000 SurveyMonkey Audience members who were marijuana users (i.e., had reported use in the past 6 months), lived in the U.S., and were young adults between the ages of 18 and 35 years (this roughly parallels young adults as defined by the U.S. Census Buruea: 18 to 34 years). Because marijuana use history is not included in an Audience member’s profile, SurveyMonkey could only target the age and residency eligibility requirements; thus, SurveyMonkey invited 18–35 year olds residing in the U.S. to take our survey. Eligibility items in the survey were then used to allow those who had used marijuana in the past 6 months and were among our age group of interest to take the survey. Two methods were used to recruit participants for our survey. SurveyMonkey sent a total of 101,822 email invitations to Audience members and “routed” 19,499 potential participants to our survey. “Routing” potential participants involves collecting basic demographic information for people who visit the SurveyMonkey website, clicking on a button indicating they would like to take a survey, and then sending that person to the applicable survey. Those invited to take the survey were not provided information on the topic of the survey until they clicked to enter the survey where they were then informed that the survey was about medical and recreational marijuana. To reach our desired sample size, a total of 21,156 people responded to the invitations (via email or “router” method); 3,176 of these met our eligibility criteria and had usable data. Although SurveyMonkey Audience recruitment uses techniques to limit low quality respondents, we included trap questions to make sure participants were reading questions thoroughly and not rushing (i.e., “Select B as your answer choice.”, “What does 2+2 equal?”); a small number of participants (69/3245; 2%) were removed because they failed these trap questions. When taking our online survey, each participant read and agreed to the informed consent document online before beginning the survey. These methods were reviewed and approved by the Washington University Institutional Review Board.

Three different survey forms were used in order to collect data on a myriad of marijuana-related items while also limiting the length of the survey to minimize participant burden. The current study centers on exposure to marijuana advertisements which was only queried on one of the three survey forms. This form had 1,006 participants, but we restricted our analysis to only those who used marijuana in the past month (to hone in on current, past month marijuana users) and were 18–34 years old which resulted in a sample size of 742. Because SurveyMonkey Audience is not nationally representative, we applied weights to our survey data so that marginal totals of our survey matched that of past-month marijuana users in the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) on age, gender, and race/ethnicity. The NSDUH is sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and is conducted annually to provide national U.S. data on substance use and mental health (United States Department of Health and Human Services et al., 2014). Thirty-five year olds were excluded from our sample because the age groups used in the NSDUH that parallel our age group of interest have a cut-off at 34 years. Weights were applied using a raking technique with the SAS rake and trim macro (AbtAssociates, n.d.). The weights were then normalized so that the sum of the weights equaled the sample size of our survey data.

2.2 Survey measures

Survey measures for domains of interest pertinent to this study are described below.

2.2.1 Exposure to marijuana advertising

To measure overall exposure to marijuana advertising, participants were asked three parallel questions about the frequency with which they saw/heard marijuana advertising: “During the past 30 days, how many times you have you SEEN or HEARD information about ... 1) advertisements/promotions, coupons or discounts for a dispensary or for buying marijuana (e.g., bud strains, marijuana concentrates, etc.) , 2) advertisements/promotions, coupons or discounts for buying tools or devices to use marijuana (e.g., bongs, rigs, vape pens), and 3) marijuana product or dispensary reviews or recommendations.” Responses for each item included “not in the past 30 days”, “1–2 times”, “3–5 times”, “6–10 times”, or “more than 10 times.” Participants were also asked to identify where they saw the above advertisements/promotions or reviews during the last 30 days. The responses included specific traditional media sources such as television, radio, print media (magazines/newspapers), or in dispensaries. New digital media sources included Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube or other video sharing sites, blogging sites like Tumblr or Pinterest, other social network sites, and online but not on social media. Participants were also given the option to write in other relevant sources that were not listed.

Next, to identify how often participants specifically sought advertisements/reviews, participants were asked “During the past 30 days, how many times have you LOOKED FOR or TRIED TO FIND information about ...” The topics provided and responses were identical to those of the parallel question described above. Participants were also asked to identify the sources where they searched for the above information, which included print media, marijuana dispensary, newsletters/membership information from dispensary, and new media sources including Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube or other video sharing sites, blogging sites like Tumblr or Pinterest, other social network sites, Weedmaps (an online directory of marijuana dispensaries), internet search engines, and online news sources. Participants were also given the option to write in other relevant sources that were not listed.

2.2.2 Marijuana use patterns

Participants were asked whether they used marijuana for medical reasons, recreationally, or for both medical and recreational reasons. Participants were also queried about their use of marijuana in the past 30 days via three separate questions that assessed the number of days the participant used 1) marijuana in its plant or bud form (e.g., smoked out of a joint, blunt, bong or bowl), 2) marijuana concentrates/extracts (concentrated forms of marijuana with high levels of THC that are heated and the resulting vapors are inhaled), and 3) marijuana edibles. We queried about different types of marijuana due to the differing concentrations of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and differing effects. Marijuana concentrates are known to have extremely high THC concentrations ranging from 40 to 80%, much higher than traditional high-grade marijuana (about 20% THC) (Drug Enforcement Administration [DEA], 2014). Ingesting marijuana in edibles typically results in longer duration of intoxication than when smoked (Perez-Reyes et al., 1973). Finally, participants were asked how many times they use marijuana per day on a typical day when they used, as well as how often they are “high” for 6 or more hours.

2.2.3 Demographic characteristics

Age, race, state of residence, education (i.e., highest level of school completed), and employment status were collected in our survey. Region of the country (four regions as defined by the U.S. Census) and legal status of marijuana were determined based on state of residence. Gender was provided for each participant by SurveyMonkey, as this data was readily available in each participant’s Audience profile.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the demographic and marijuana use characteristics of the sample and the prevalence and sources of exposure to advertising for marijuana and marijuana-related products. Bivariate associations between exposure to marijuana-related advertising with demographic characteristics and marijuana use characteristics were assessed using Rao-Scott Chi Square tests. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted with SAS for Windows version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) using survey procedures to apply the survey weights.

3. Results

3.1 Participant demographic and marijuana use characteristics

Table 1 provides the demographic and marijuana use characteristics of our study participants. Over 60% of current marijuana users were male and White, and the median age was 23 years (range 18–34). About ¾ had at least some college education, nearly ¾ were employed, and nearly 1/3 lived in the Western U.S. Over 60% lived in a state where either medical or recreational marijuana use was legal.

Table 1.

Demographic and marijuana use characteristics of current marijuana users (Total N=742 unless otherwise noted)

| Demographic characteristic | Weighted n (column %) | Marijuana use characteristic | Weighted n (column %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Reason(s) for using marijuana | ||

| Male | 460 (62) | Recreational reasons only | 424 (57) |

| Female | 282 (38) | Medical reasons only | 111 (15) |

| Age | Both medical and recreational | 207 (28) | |

| 18–19 years | 112 (15) | Use of plant-based marijuana in past 30 days (n=740) | |

| 20–21 years | 122 (16) | ||

| 22–23 years | 114 (15) | 0 days | 32 (4) |

| 24–25 years | 91 (12) | 1–2 days | 242 (33) |

| 26–29 year | 153 (21) | 3–5 days | 94 (13) |

| 30–34 years | 150 (20) | 6–9 days | 60 (8) |

| Race | 10–19 days | 89 (12) | |

| White | 468 (63) | 20–29 days | 97 (13) |

| Black | 116 (16) | 30 days | 125 (17) |

| Hispanic | 109 (15) | Use of marijuana concentrates in past 30 days (n=713) | |

| Other | 49 (7) | ||

| Education | 0 days | 506 (71) | |

| ≤ High school | 184 (25) | 1–2 days | 115 (16) |

| Some college | 326 (44) | 3–5 days | 32 (5) |

| ≥ Bachelor’s degree | 232 (31) | 6–9 days | 17 (2) |

| Employment (n=735) | 10–19 days | 12 (2) | |

| Employed | 533 (73) | 20–29 days | 9 (1) |

| Unemployed | 51 (7) | 30 days | 23 (3) |

| Other (e.g., student, homemaker) | 151 (21) | Use of marijuana edibles in past 30 days (n=718) | |

| U.S. Census region (n=726) | |||

| Northeast | 149 (20) | 0 days | 492 (68) |

| Midwest | 148 (20) | 1–2 days | 153 (21) |

| South | 202 (28) | 3–5 days | 36 (5) |

| West | 228 (31) | 6–9 days | 16 (2) |

| Legal status of marijuana in state (n=726) | 10–19 days | 6 (1) | |

| Both recreational and medical | 87 (12) | 20–29 days | 1 (>1) |

| Only medical use | 354 (49) | 30 days | 13 (2) |

| Use is not legal | 285 (39) | Number of marijuana sessions on a typical day when use | |

| 1 time | 339 (46) | ||

| 2–3 times | 288 (39) | ||

| 4–5 times | 61 (8) | ||

| ≥6 times | 53 (7) | ||

| Frequency “high” for 6 or more hours (n=741) | |||

| Never | 361 (49) | ||

| Once a month | 164 (22) | ||

| 2–4 times per month | 103 (14) | ||

| 5–12 times per month | 47 (6) | ||

| ≥12 times per month | 66 (9) |

Over half used marijuana for recreational reasons only, while 28% used for both medical and recreational reasons and 15% used for medical reasons only. Over 95% had used plant-based marijuana products in the past 30 days, while 29% and 32% used marijuana concentrates and edibles, respectively. Over half used marijuana more than once on a typical day when they used, and about half were high for 6 or more hours at a time at least once per month.

3.2 Exposure to and sources of marijuana advertisements

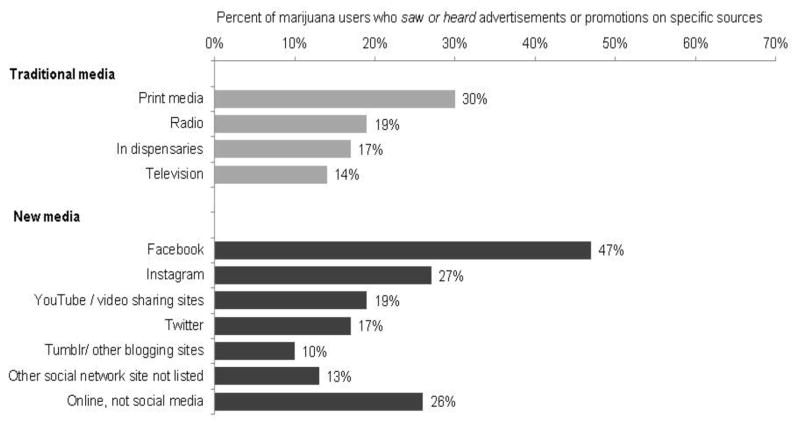

The prevalence of seeing or hearing specific types of marijuana advertisements in the past 30 days is shown in Table 2 (left-most column of n and percents). Overall, 48% of marijuana users saw or heard marijuana advertisements in the past 30 days, and this differed significantly by the legal status of marijuana in the state in which the person resided. Sixty-six percent of participants in states where recreational use was legal reported seeing or hearing advertisements, compared to 47% in states where medical use was legal and 46% in states where use was not legal (Rao-Scott Χ2 (df=2)=8.1, p=0.017). Seeing or hearing advertisements for tools or devices for using marijuana was most common (about 40%), but 28% saw or heard advertisements for dispensaries or marijuana itself and 28% saw or heard marijuana reviews/recommendations. The sources of these advertisements are shown in Figure 1. Among those who saw or heard advertisements in the past 30 days, the most common source of advertisements was social media (67%), with Facebook and Instagram being the most common platforms (47% and 27% respectively), followed by print media (30%) and online sources other than social media (26%). Common responses to “other” sources included public signage or billboards (5%) and text/email messages (1%). Among those who saw or heard advertisements, observing advertisements on new digital media including social media, online, or text/emails (77%) was more common than observing ads via traditional media including print, television, radio, and dispensaries (55%).

Table 2.

Exposure to marijuana advertising among current marijuana users

| Type of advertising information exposed to in the past 30 days | Saw or heard the information Weighted n (column %) | Looked for or tried to find the information Weighted n (column %) |

|---|---|---|

| Advertisement/promotion, coupons or discounts for buying tools or devices to use marijuana (e.g., bongs, rigs, vape pens) | N=741 | N=740 |

| Not in the past 30 days | 443 (60) | 610 (82) |

| 1–2 times | 167 (22) | 81 (11) |

| 3–5 times | 75 (10) | 34 (5) |

| ≥6 times | 57 (8) | 15 (2) |

| Advertisement/promotion, coupons or discounts for a dispensary or for buying marijuana (e.g., bud strains, concentrates etc.) | N=740 | N=740 |

| Not in the past 30 days | 534 (72) | 623 (84) |

| 1–2 times | 113 (15) | 73 (10) |

| 3–5 times | 53 (7) | 32 (4) |

| ≥6 times | 40 (6) | 13 (2) |

| Marijuana product or dispensary reviews or recommendations | N=732 | N=740 |

| Not in the past 30 days | 530 (72) | 595 (80) |

| 1–2 times | 118 (16) | 96 (13) |

| 3–5 times | 51 (7) | 28 (4) |

| ≥6 times | 33 (5) | 20 (3) |

Figure 1.

Sources of seeing or hearing advertisements among marijuana users that observed such advertisements in the past 30 days (weighted N=332; 24 did not respond to this item)

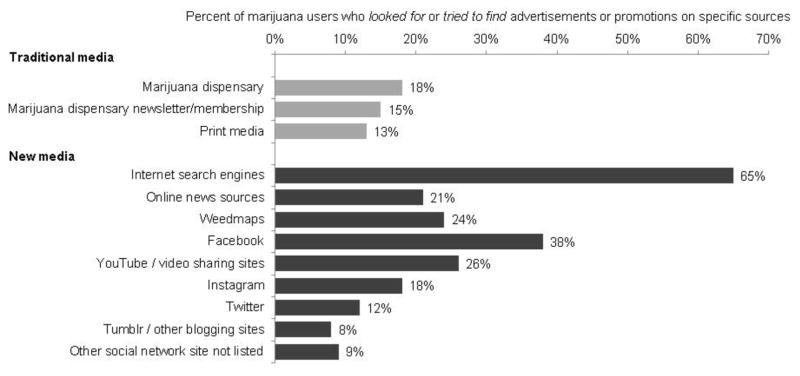

The prevalence of seeking marijuana advertisements in the past 30 days is also shown in Table 2 (right-most column). Overall, 26% sought marijuana advertisements in the past 30 days, and this did not differ significantly by legal status of marijuana in the state (recreational states 31%, medical states 25%, states where use was not legal 27%; Rao-Scott Χ2 (df=2)=0.7, p=0.698). Approximately 16% to 20% saw each type of advertisement (i.e., for dispensaries or buying marijuana, for tools/devices to use marijuana, and reviews/recommendations). Sources for seeking marijuana advertisements in the past 30 days are shown in Figure 2. The most used sources for seeking advertisements were Internet search engines (65%) and social media sources (53%), the most common of which was Facebook (38%) followed by YouTube or other video sharing sites (26%). Another popular source for seeking advertisements was Weedmaps (24%), an online directory where users can find information including menu items and product specials for nearby dispensaries. A similar online directory, Leafly, was written in by participants as an “other” source for seeking advertisements (4%).

Figure 2.

Sources for looking for or trying to find advertisements among marijuana users that sought such advertisements in the past 30 days (weighted N=177; 18 did not respond to this item)

3.3 Levels of advertising exposure and correlates

When categorizing marijuana users into three categories of exposure to marijuana advertisements, 45% of users had no exposure (i.e., had not observed or sought marijuana advertisements), 28% had merely observed advertisements but did not actively seek them, and 26% had actively sought marijuana advertisements in the past 30 days. Significant results from bivariate comparisons between demographic and marijuana use characteristics with level of advertising exposure are shown in Table 3. Among demographic characteristics, only gender was significantly associated with level of advertising exposure, as males were more likely to seek advertisements (31%) than females (19%). Although seeing or hearing advertisements was significantly associated with legal status of marijuana in the participant’s state of residence (as reported above), when categorizing data into three levels of advertising exposure (no exposure, passive exposure, actively seeking) the association did not reach statistical significance (Rao-Scott Χ2 (df=2)=7.4, p=0.117).

Table 3.

Significant bivariate associations between level of marijuana advertising exposure and participant characteristicsa

| Participant characteristic | Level of exposure to marijuana advertising | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No exposure | Saw or heard ads only | Looked for or tried to find ads | |||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | Weighted n (row %) | 192 (42) | 124 (27) | 141 (31) | 0.009 |

| Female | 141 (50) | 86 (31) | 53 (19) | ||

| Reason for using marijuana | |||||

| Medical | Weighted n (row %) | 42 (38) | 23 (21) | 45 (41) | <0.001 |

| Recreational | 212 (50) | 135 (32) | 75 (18) | ||

| Both | 80 (39) | 52 (25) | 75 (36) | ||

| Used concentrates in past 30 days | |||||

| Yes | Weighted n (row %) | 63 (30) | 53 (26) | 91 (44) | <0.001 |

| No | 257 (51) | 144 (29) | 101 (20) | ||

| Used edibles in past 30 days | |||||

| Yes | Weighted n (row %) | 76 (34) | 53 (24) | 97 (43) | <0.001 |

| No | 245 (50) | 150 (31) | 93 (19) | ||

| When use marijuana, use ≥2 times per day | |||||

| Yes | Weighted n (row %) | 168 (42) | 101 (25) | 130 (33) | 0.004 |

| No | 166 (49) | 108 (32) | 65 (19) | ||

| High for ≥ 6 more hours at least once per month | |||||

| Yes | Weighted n (row %) | 142 (38) | 100 (26) | 136 (36) | <0.001 |

| No | 191 (53) | 109 (30) | 58 (16) | ||

There were no significant associations between level of marijuana advertising exposure and age, race, education, employment, legal status of marijuana in the state, and use of plant-based marijuana products.

Several marijuana use characteristics were associated with level of advertising exposure (Table 3). Seeking advertisements was more common among those who used marijuana for medical reasons (41%) or for both medical and recreational reasons (36%) than those who used for recreational reasons only (18%). Those who had used concentrates or edibles in the past 30 days were also more likely to seek ads (44% and 43%, respectively) than those who had not used concentrates or edibles (20% and 19%, respectively) in the past 30 days. Finally, seeking marijuana advertisements was more common among those who used marijuana multiple times per day (33%) or were high for 6 or more hours at least once per month (36%) compared to users who did not have multiple marijuana sessions in a day (19%) or were not high for 6 or more hours (16%).

Of note, those who used marijuana for only medical reasons or for both medical and recreational reasons appeared more likely to use concentrates (55% and 37%, respectively) than those who used for recreational reasons only (19%) (Rao-Scott Χ2 (df=2)=38.9, p<0.001). Similarly, 50% of those who used for only medical reasons used edibles versus 28% among those who used only recreationally and 29% among those who used for both reasons (Rao-Scott Χ2 (df=2)=13.6, p=0.001). Those who used for only medical purposes and those who used for both medical and recreational reasons were also more likely to use multiple times per day (73% and 77%, respectively) or to have been high for 6 or more hours per month (56% and 68%, respectively) than those who only used recreationally (38% and 42%) (Rao-Scott Χ2 (df=2)=81.0, p<0.001; Rao-Scott Χ2 (df=2)=25.6, p<0.001). Reason for medical use was not significantly associated with legal status of marijuana in the state (Rao-Scott Χ2 (df=4)=1.3, p=0.867). However, using multiple times per day was more common in states where marijuana was not legal (61%) compared to recreational (47%) or medical states (46%) (Rao-Scott Χ2 (df=2)=16.0, p<0.001).

4. Discussion

This survey was the first of its kind to explore the prevalence and sources of exposure to marijuana advertising among current young adult marijuana users in the U.S. In this study, marijuana advertisements were relatively commonly observed among marijuana users, with nearly half reporting that they had seen or heard such advertisements in the past 30 day, and approximately a quarter of users actively seeking such advertisements. As expected, seeing or hearing marijuana advertisements was more common in states where recreational use was legal than in states where only medical use was legal or use was not legal. Furthermore, our study highlighted the prevalence of observing marijuana advertisements online or on social media, which was more common than viewing advertisements on traditional media sources such as print, radio, and television. Finally, viewing or seeking advertisements was more common among medical users, those who used novel products such as edibles and concentrates, and heavier users. The implications of each of these findings are discussed below.

The fact that many marijuana users viewed or looked for advertisements online or on social media is not surprising. In general, digital advertising spending has been the most rapidly growing area of media spending in recent years and is expected to surpass that of television advertising in 2017 (Bagchi et al., 2015; eMarketer, 2016a). Although a few states address restrictions to marijuana marketing via digital sources (e.g., no more than 30% of the online audience can be underage), most do not, and there are difficulties in regulating digital advertising. Although Facebook, the most popular social media site, prohibits advertising of illegal drugs and has even shut down some marijuana dispensary Facebook pages (Breen, 2016; Duggan, 2015; eMarketer, 2016b; Facebook, 2016), this platform was still the most common source of exposure to marijuana advertising on a social media site in our study. It is possible that participants did not distinguish commercial marijuana promotions from more “organic” marijuana promotions (i.e., references to marijuana from friends etc.). Nevertheless, regulation of online advertising for other substances and preventing underage access has been found to be challenging. Despite banning tobacco advertising on its platform, cigarette brand fan pages were easily found on Facebook (Liang et al., 2015). Furthermore, specific brands of e-cigarettes have been found to advertise on websites with an audience of up to 35% youth (Richardson et al., 2014), and underage Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube users can easily access and interact with alcohol industry content on these platforms (Barry, Bates, et al., 2015; Barry, Johnson, et al., 2015).

Although we cannot speak to how many underage youth are exposed to marijuana advertising based on our study, the prevalence of young adult users who see such advertisements online and on social media sites where youth are known to spend a lot of time (Common Sense, 2015) highlights the need for increased monitoring as well as research into better methods to regulate online advertising. Restrictions on advertisements via traditional media also cannot be ignored, as users in our study were also exposed to advertisements via sources like print media, radio, and dispensaries. For these venues, states can learn from the research on comprehensive marketing restrictions adopted for the tobacco industry which have helped to prevent youth initiation and tobacco consumption (Gilpin et al., 2004; Henriksen, 2012; Saffer and Chaloupka, 2000).

Another important finding from our study was that seeking marijuana advertisements was more common among medical marijuana users, users of novel products (i.e., marijuana concentrates, edibles) that are more potent and/or result in longer intoxication duration (DEA, 2014; Perez-Reyes et al., 1973), and those who used multiple times per day or spent several hours high per month. Notably, these measures were somewhat confounded as medical use was associated with heavier use and use of concentrates or edibles. Prior studies have also reported that medical marijuana users tend to use more frequently than non-medical marijuana users (Boyd et al., 2015; Roy-Byrne et al., 2015; Woodruff and Shillington, 2016). Because medical users use more regularly than recreational users and would be consistently purchasing products to treat their medical conditions, such users might accordingly be seeking information about products and discounts/deals from nearby dispensaries. Access to medical dispensaries might also facilitate the transition to use a variety of marijuana products, including those with higher THC levels which have been associated with cannabis-induced psychosis (Murray et al., 2016; Pierre et al., 2016). Nonetheless, while we cannot delineate causal relationships from this cross-sectional study, prior longitudinal studies of tobacco and alcohol have shown that exposure to substance use advertising promotes the initiation and the continuation of using these substances (Anderson et al., 2009; Lovato et al., 2003). In addition, D’Amico et. al’s (2015) longitudinal study of middle school students found cross-lagged reciprocal associations between medical marijuana advertising exposure and current marijuana use (i.e., initial advertising exposure was associated with higher likelihood of marijuana use one year later, and initial marijuana use was associated with higher likelihood of advertising exposure one year later). Additional longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether exposure to marijuana advertising leads to initiation of use among non-users of differing age groups, leads to increased frequency or quantity of use among experimental users, or the exploration of higher-potency marijuana products among both medical and non-medical users.

Notably, there were few differences in advertising exposure by demographic characteristic of the participant. Men were more likely to seek advertisements than women, and, as noted earlier, participants living in states where recreational use is legal were more likely to view or hear marijuana advertisements. This is likely due to the large number of marijuana dispensaries in such states (e.g., October 2016, Oregon had over 420 marijuana dispensaries, Colorado had over 500 dispensaries with a license for medical sales and 450 with a license for recreational sales, and Washington had nearly 500 dispensaries with a recreational license and nearly 400 with a medical license) (Colorado Department of Revenue, 2015; Oregon Health Authority, 2016; Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board, 2016). However, we did not find significant differences in level of advertising exposure by other demographic characteristics (age, race, education, employment status). Although advertising of other substances, like alcohol and tobacco, has been known to target racial/ethnic minority groups or low socioeconomic groups (Barbeau et al., 2004; Moore et al., 1996), our study did not suggest this was the case with marijuana advertising. Related, geospatial studies of marijuana dispensaries and socioeconomic indicators in Los Angeles and Denver found no association between density of dispensaries and the percentage of Black residents, high poverty or concentrated disadvantage (Boggess et al., 2014; Thomas and Freisthler, 2016). Yet, the Los Angeles study did find that dispensary density was associated with greater percentage of Hispanic residents (Thomas and Freisthler, 2016). In any case, marijuana advertising research is still in its infancy and the possibility of targeted advertising to subgroups should be examined in future studies.

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of our study. Our study is based on self-reported survey data, and participants might have been hesitant to respond honestly or might not accurately recall the advertisements they observed or the venues on which they saw them. While our survey was not administered to a nationally representative sample, we did weight participants to match the distribution of marijuana users on basic demographic characteristics from a large national survey. Our survey was cross-sectional in nature and causal associations cannot be inferred from significant associations. We did not include all potential sources of advertisements, which could have limited the reporting of some specific locations (e.g., billboards). In our line of questioning, we did not specifically define the advertisements as commercial or coming from a marijuana business. Participants might have included other noncommercial marijuana promotions and reviews from online friends on social media in their response (instead of distinguishing such conversations from commercial advertisements), which could lead to an overestimation of exposure to advertising. Finally, our survey of marijuana use behaviors targeted young adults, as young adults have the greatest prevalence of marijuana use (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, 2016). While our study is among the largest to examine marijuana advertising exposure among young adult marijuana users, we did not include non-users or youth in our study; thus we cannot report on the prevalence of exposure to marijuana advertising among these groups. Longitudinally assessing such groups would be necessary to determine effects of advertising exposure on initiation of marijuana use behaviors.

5.0 Conclusions

This study is the first to quantify the level of exposure to and sources of marijuana advertising among current young adult marijuana users. There was a high prevalence of exposure to such advertisements, as over half of the participants had been exposed to marijuana advertising in some way. Furthermore, advertising on new media sources such as online or on social media was more common than traditional media sources like print or radio. Those who sought marijuana advertisements were more likely to be medical users, to use heavily, and use novel marijuana forms that are more potent or have greater intoxication duration. As more states legalize both medical and recreational marijuana consumption, it will be important to monitor who is exposed to advertisements, including youth and non-users, where advertisements are being seen, and the content of such advertisements in order to provide recommendations for necessary restrictions. It will also be crucial to examine the potential causal associations between exposure to such advertisements and patterns of marijuana use.

Highlights.

Surveyed 18–34 year old past month marijuana users living in the U.S. (N=742).

Over half of participants were exposed to marijuana advertising in the past month.

Advertisements were commonly viewed on digital media (i.e. online, social media).

Exposure to marijuana advertising was associated with heavier, more potent use.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

One of the authors, Dr. Bierut, is listed as an inventor on Issued U.S. Patent 8, 080, 371, “Markers for Addiction,” covering the use of certain SNPs in determining the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of addiction. All other authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributors

Ms. Krauss led the acquisition of the data, analyses, interpretation of results and manuscript writing. Ms. Sowles assisted with the study design, acquisition of the data and critically revised the manuscript. Miss Sehi participated in data analysis, interpretation of results, and drafting the manuscript. Dr. Spitznagel participated in data analysis and interpretation of results. Dr. Berg and Dr. Bierut contributed to interpretation of results and critical revisions to the manuscript. Dr. Cavazos-Rehg provided mentoring on all aspects of the project, including the study design, acquisition of the data, analyses, interpretation of results, and revisions to the manuscript. All authors approved of the final manuscript before submission.

Role of Funding Source

The funders had no involvement in the study design; the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abt Associates. [accessed 09.01.16];Raking Survey Data (a.k.a. Sample Balancing) 2016 http://abtassociates.com/Expertise/Surveys-and-Data-Collection/Raking-Survey-Data-(a-k-a--Sample-Balancing).aspx.

- Anderson P, de Bruijn A, Angus K, Gordon R, Hastings G. Impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44:229–243. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agn115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ArcView Market Research. [accessed 10.17.16];Executive Summary: The State Of Legal Marijuana Markets. 2015 https://static1.squarespace.com/static/526ec118e4b06297128d29a9/t/56f21ed59f7266ee27800d7b/1458708198877/Executive+Summary+-+The+State+of+Legal+Marijuana+Markets+-+4th+Edition.pdf.

- Bagchi M, Murdoch S, Scanlan J. [accessed 09.01.16];The state of global media spending. 2015 http://www.mckinsey.com/industries/media-and-entertainment/our-insights/the-state-of-global-media-spending.

- Barbeau EM, Leavy-Sperounis A, Balbach ED. Smoking, social class, and gender: What can public health learn from the tobacco industry about disparities in smoking? Tob Control. 2004;13:115–120. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006098. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tc.2003.006098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry AE, Bates AM, Olusanya O, Vinal CE, Martin E, Peoples JE, Jackson ZA, Billinger SA, Yusuf A, Cauley DA, Montano JR. Alcohol marketing on Twitter and Instagram: Evidence of directly advertising to youth/adolescents. Alcohol Alcohol. 2015;51:1–6. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agv128. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agv128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry AE, Johnson E, Rabre A, Darville G, Donovan KM, Efunbumi O. Underage access to online alcohol marketing content: A YouTube case study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2015;50:89–94. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agu078. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agu078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierut T, Krauss MJ, Sowles SJ, Cavazos-Rehg PA. Exploring marijuana advertising on Weedmaps, a popular online directory. Prev Sci. 2016:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0702-z. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0702-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Boggess LN, Perez DM, Cope K, Root C, Stretesky PB. Do medical marijuana centers behave like locally undesirable land uses? Implications for the geography of health and environmental justice Urban Geogr. 2014;35:315–336. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2014.881018. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CJ, Veliz PT, McCabe SE. Adolescents’ use of medical marijuana: A secondary analysis of monitoring the future data. J Adolesc Health. 2015;57:241–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen M. [accessed 09.01.16];Why Is Facebook Taking Down Marijuana Dispensary Pages? 2016 http://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/why-facebook-taking-down-marijuana-dispensary-pages-n514976.

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Key Substance Use And Mental Health Indicators In The United States: Results From The 2015 National Survey On Drug Use And Health. 2016 (HHS Publication No. SMA 16-4984, NSDUH Series H-51). https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/NSDUH-FFR1-2015/NSDUH-FFR1-2015.pdf.

- Choi WS, Ahluwalia JS, Harris KJ, Okuyemi K. Progression to established smoking: The influence of tobacco marketing. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:228–233. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00420-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00420-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colorado Department of Revenue. [accessed 09.01.16];MED Licensed Facilities. 2015 https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/enforcement/med-licensed-facilities.

- Common Sense. The Common Sense Census: Media Use By Tweens And Teens. Common Sense Media Inc; 2015. [accessed 10.17.16]. http://static1.1.sqspcdn.com/static/f/1083077/26645197/1446492628567/CSM_TeenTween_MediaCensus_FinalWebVersion_1.pdf?token=DyqCzLrJhC4AG9hClTczCD9uJyE%3D. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico EJ, Miles JNV, Tucker JS. Gateway to curiosity: Medical marijuana ads and intention and use during middle school. Psychol Addict Behav. 2015;29:613–619. doi: 10.1037/adb0000094. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/adb0000094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K, Gilpin E, Loken B, Viswanath K, Wakefield M. Themes And Targets Of Tobacco Advertising And Promotion. Tobacco Control Monograph Series 19: The Role of the Media in Promoting and Reducing Use. 2008:141–178. [Google Scholar]

- Drug Enforcement Administration (Demand Reduction Section) What You Should Know About Marijuana Concentrates. United States Department of Justice; 2014. [accessed 01.03.17]. https://www.dea.gov/pr/multimedia-library/publications/marijuana-concentrates.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Duggan M. [accessed 03.22.16];Mobile Messaging And Social Media. 2015 http://www.pewinternet.org/files/2015/08/Social-Media-Update-2015-FINAL2.pdf.

- eMarketer. [accessed 09.01.16];Digital Ad Spending To Surpass TV Next Year. 2016a http://www.emarketer.com/Article/Digital-Ad-Spending-Surpass-TV-Next-Year/1013671.

- eMarketer. [accessed 09.01.16];Facebook Remains The Largest Social Network In Most Major Markets. 2016b http://www.emarketer.com/Article/Facebook-Remains-Largest-Social-Network-Most-Major-Markets/1013798.

- Evans N, Farkas A, Gilpin E, Berry C, Pierce JP. Influence of tobacco marketing and exposure to smokers on adolescent susceptibility to smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1538–1545. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.20.1538. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jnci/87.20.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facebook. [accessed 09.01.16];Advertising Policies. 2016 https://www.facebook.com/policies/ads/

- Gilpin E, Distefan J, Pierce J. Population receptivity to tobacco advertising/promotions and exposure to anti-tobacco media: Effect of Master Settlement Agreement in California: 1992–2002. Health Promot Pract. 2004;5:91S–98S. doi: 10.1177/1524839904264601. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1524839904264601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin EA, White MM, Messer K, Pierce JP. Receptivity to tobacco advertising and promotions among young adolescents as a predictor of established smoking in young adulthood. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1489–1495. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.070359. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.070359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon R, MacKintosh AM, Moodie C. The impact of alcohol marketing on youth drinking behaviour: A two-stage cohort study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:470–480. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agq047. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agq047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen L. Comprehensive tobacco marketing restrictions: promotion, packaging, price and place. Tob Control. 2012;21:147–153. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050416. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones J. [accessed 08.31.16];In U.S., 58% Back Legal Marijuana Use. 2015 http://www.gallup.com/poll/186260/back-legal-marijuana.aspx?g_source=marijuana%20legalization&g_medium=search&g_campaign=tiles.

- Leafly. [accessed 08.31.16];State-By-State Guide To Cannabis Advertising Regulations. 2016 https://www.leafly.com/news/industry/state-by-state-guide-to-cannabis-advertising-regulations/

- Liang Y, Zheng X, Zeng DD, Zhou X, Leischow SJ, Chung W. Exploring how the tobacco industry presents and promotes itself in social media. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e24. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3665. http://dx.doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovato C, Linn G, Stead LF, Best A. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003:1–26. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003439. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd003439. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Marijuana Policy Project, 2017 Marijuana Policy Project. [Accessed 03.16.2017];State Policy, 2017. https://www.mpp.org/states/

- Moore DJ, Williams JD, Qualls WJ. Target marketing of tobacco and alcohol-related products to ethnic minority groups in the United States. Ethn Dis. 1996;6:83–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray RM, Quigley H, Quattrone D, Englund A, Di Forti M. Traditional marijuana, high-potency cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids: Increasing risk for psychosis. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:195–204. doi: 10.1002/wps.20341. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/wps.20341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oregon Health Authority. [accessed 10.14.16];Medical Marijuana Dispensary Directory. 2016 http://public.health.oregon.gov/DiseasesConditions/ChronicDisease/MedicalMarijuanaProgram/Pages/dispensary-directory.aspx.

- Perez-Reyes M, Lipton MA, Timmons MC, Wall ME, Brine DR, Davis KH. Pharmacology of orally administered 9-tetrahydrocannabinol. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1973;4:48–55. doi: 10.1002/cpt197314148. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cpt197314148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. [accessed 08.31.16];America’s new drug policy landscape. 2014 http://www.people-press.org/2014/04/02/americas-new-drug-policy-landscape/

- Pierre JM, Gandal M, Son M. Cannabis-induced psychosis associated with high potency “wax dabs”. Schizophrenia Res. 2016;172:211–212. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.01.056. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2016.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A, Ganz O, Vallone D. Tobacco on the web: Surveillance and characterisation of online tobacco and e-cigarette advertising. Tob Control. 2014:1–7. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051246. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051246. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Roy-Byrne P, Maynard C, Bumgardner K, Krupski A, Dunn C, West II, Donovan D, Atkins DC, Ries R. Are medical marijuana users different from recreational users? The view from primary care. Am J Addict. 2015;24:599–606. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12270. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffer H, Chaloupka F. The effect of tobacco advertising bans on tobacco consumption. J Health Econ. 2000;19:1117–1137. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(00)00054-0. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-6296(00)00054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LA, Foxcroft DR. The effect of alcohol advertising, marketing and portrayal on drinking behaviour in young people: Systematic review of prospective cohort studies. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sola K. [accessed 08.31.16];Legal U.S. Marijuana Market Will Grow To $7.1 Billion In 2016: Report. 2016 http://www.forbes.com/sites/katiesola/2016/04/19/legal-u-s-marijuana-market-will-grow-to-7-1-billion-in-2016-report/print/

- Stebbins S, Comen E. [accessed 08.31.16];The Next 14 States To Legalize Marijuana. 2016 http://247wallst.com/special-report/2016/08/19/14-next-states-to-legalize-pot/

- Thomas C, Freisthler B. Examining the locations of medical marijuana dispensaries in Los Angeles. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2016;35:334–337. doi: 10.1111/dar.12325. http://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2014 ICPSR36361-v1 http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36361.v1.

- Washington State Liquor and Cannabis Board. [accessed 10.14.16];Frequently Requested Lists. 2016 http://lcb.wa.gov/records/frequently-requested-lists.

- Woodruff SI, Shillington AM. Sociodemographic and drug use severity differences between medical marijuana users and non-medical users visiting the emergency department. Am J Addict. 2016;25:385–391. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12401. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ajad.12401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wronski L, Liu M. Calibrating cross-national panel surveys. International Conference on Survey Methods in Multinational, Multiregional and Multicultural Contexts (3MC); Chicago, IL. July 25–29, 2016; 2016. https://www.csdiworkshop.org/images/2016_3MC_Presentations/Wronski_Calibrating-Cross-National-Panel-Surveys.pdf. [Google Scholar]