Abstract

Purpose

To study the magnitude of chronic diseases among patients suffering from Dry Eye Syndrome (DES) and compare them with published findings in the literature.

Methods

Patients diagnosed in 2016 suffering from DES based on presenting symptoms and findings of ocular examination were included in this study. The demographic information included age and gender. Chronic diseases among them were identified through case records, assessment and ongoing medications.

Results

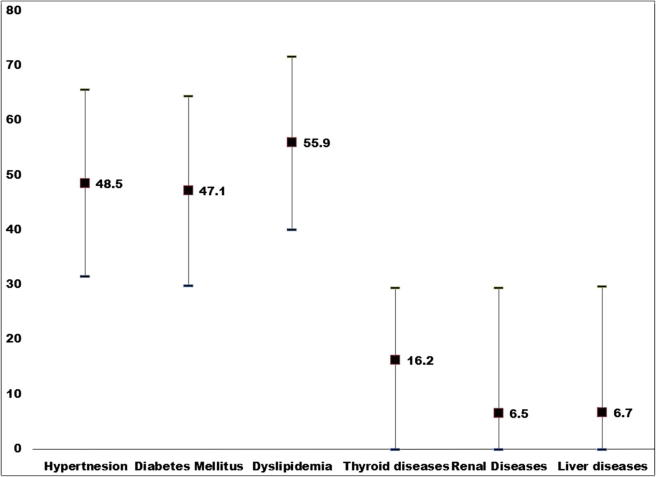

This case series had 62 patients (58% males) of DES. The mean age was 60.2 ± 16.6 years. The prevalence of hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes among them was 48.5% (95% confidence interval (CI) 31.5–65.5), 55.9% (95% CI 40.1–71.7) and 47.1% (95% CI 29.8–64.4) respectively. The rate of thyroid diseases (16.2%), renal diseases (6.5%), and liver diseases (6.7%) was not significant in this series.

Conclusions

This series in central Saudi Arabia suggests that the magnitude of chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, obesity and dyslipidemia seems to be higher in patients with DES compared to the population.

Keywords: DES, Diabetes, Hypertension, Chronic diseases

Introduction

Dry eye syndrome is also known as Kerato-Conjunctivitis Sicca is characterized by tear deficiency resulting in damage to cornea and conjunctiva in inter palpebral area reflected mainly as ocular discomfort.1, 2 It has been associated with systemic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension.3, 4 In addition, more stress is emphasized on climatic changes in modern urban life and its negative effect on DES.5

The magnitude and risk factors of DES in global population have been studied.6 A study on DES was also conducted in Saudi Arabia. However, it was in the coastal town of Jeddah.7 The climate in central Saudi Arabia is different from Jeddah, a coastal city. In the central area, the humidity is less than 20% throughout the year and temperature remains high during day time. Thus, eye diseases related to sunlight are likely to be high.8 The population staying indoor with temperature maintained by air conditioners faces negative effects of such artificial environment on tear film.9

The magnitude and association of DES among diabetic population were studied in central Saudi Arabia.10 But to the best of our knowledge, no study about chronic diseases among DES is conducted in central Saudi Arabia.

We present the profile of chronic diseases among patients with Dry eye syndrome (DES) examined at a tertiary institute of central Saudi Arabia.

Methods and materials

This case series type of study was approved by the ethical and research board of the institute. The study was conducted at King Abdulaziz Medical City (KAMC) and National Guard Comprehensive Specialized Clinics (NGCSC) in Riyadh in 2016.

Research investigators were the field staff. They were involved in both assessment and management. The participants were recruited from the tertiary level of health institution in central Saudi Arabia.

The DES was defined as the presence of patient related outcomes (PRO) symptoms such as grittiness, redness, foreign body sensations, hotness and sand-like sensations.9 The diagnosis could be confirmed by typical signs observed using slit lamp bio-microscopy (Topcon, USA) and fluorescein staining of the tear film.2, 11

The information of chronic systemic diseases included physical measurements, history of ailment diagnosed and ongoing treatment for ailment.12 Diabetes was defined as HbA1c of more than 6.5. In a patient who was already taking a medication to control blood sugar, he/she was defined as diabetic despite good blood sugar levels. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure more than 140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure more than 85 mmHg. If patient was already having hypertension and taking medication to reduce hypertension, their lower pressure was ignored. In young patients, systolic blood pressure of more than 120 was considered as high BP. The other metabolic syndromes were defined as per another study in Saudi Arabia.13 The obesity was grouped as per World Health Organization recommended classification.14 The levels of lipids were further used to classify the dyslipidemia in our series based on the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists.15

The data were collected on pretested data collection forms. Then it was transferred into spreadsheet of Microsoft XL®. Then it was shifted to the Spreadsheet of Statistical Package for Social Studies (SPSS 23) (IMB, NY, USA). Univariate analysis using parametric method was carried out. For qualitative variables, we calculated frequencies, percentage proportions. For quantitative variable, we firstly studied distribution and when found normal, we calculated the mean and standard deviation. To estimate the prevalence of chronic diseases among patients with DES, we presented the findings with 95% confidence interval.

Results

Our series had 62 patients of bilateral DES. Their mean age was 60.2 ± 16.6 years. Male comprised of 58% of the participants.

The magnitude of different chronic metabolic diseases among participants of DES is given in Table 1 and Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Profile of patients with Dry Eye Syndrome.

| Quantitative variables | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Mean | 60.2 | |

| Standard deviation | 16.6 | ||

| Body Mass Index (kg/M2) | Mean | 29.2 | |

| Standard deviation | 5.9 | ||

| Qualitative variable | Number | Percentage | |

| Gender | Male | 36 | 58.1 |

| Female | 26 | 41.9 | |

| Age group | 20 to 39 | 7 | 11.3 |

| 40 to 59 | 22 | 35.5 | |

| 60 and more | 33 | 53.2 | |

| Obesity* | Thin | 0 | 0.0 |

| Normal | 15 | 24.2 | |

| Pre-obese | 24 | 38.7 | |

| Obese I | 11 | 17.7 | |

| Obese II | 9 | 14.5 | |

| Obese III | 3 | 4.8 | |

Classification of Obesity as recommended by WHO.14

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of chronic metabolic diseases among patients with Dry Eye Syndrome (DES). X axis denotes different chronic metabolic diseases. Y axis denotes percentage proportions of the prevalence rate. ■ Prevalence rate with lower and higher values of 95% confidence interval.

The prevalence of these chronic diseases in Saudi Arabia or other gulf countries among adult population as given in published articles is given in Table 2 for comparison. Chronic metabolic diseases included diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia and obesity among patients with Dry Eye Syndrome (DES) compared to the rate among adult Saudi population.

Table 2.

Comparison of prevalence of chronic metabolic diseases among adult Saudi population to the patients with Dry Eye Syndrome (DES) of the present study.

| Authors | Area | Year | Prevalence rate | Rate in our study | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | Meo SA16 | KSA | 2015 | 32.8 | 47.1 | 29.8–64.4 |

| Behijri SM et al.17 | Jeddah | 2016 | 18.3 | |||

| AlQuwaidhi HA et al.18 | KSA | 2011 | 29.2 | |||

| Hypertension | Al Nozha MM et al.19 | KSA | 2007 | 26.1 | 48.5 | 31.5–65.6 |

| Al-Dhagri NM et al.20 | Central KSA | 2011 | 32.6 | |||

| Dyslipidemia | Al-Dhagri NM et al.21 | Central KSA | 2010 | 34% | 55.9 | 40.1–71.7 |

| Obesity | 40 | 37% | 18.1 – 55.9 | |||

| Thyroid diseases | Akbar DH et al.22 | Jeddah KSA | 2006 | Diabetic: 26 | 16.2 | <0.0–29.5 |

| Nondiabetic: 2 | ||||||

| Renal diseases | Alsuwaida AO et al.23 | Riyadh, KSA | 2010 | 5.7 | 6.5 | <0.0–29.5 |

| Liver diseases | Al-Hamoudi W et al.24 | Riyadh, KSA | 2012 | Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD); 16.6 | 6.7 | <0.0–29.7 |

| Al-Faleh F et al.25 | Riyadh, KSA | 2008 | Hepatitis A: 18.6 | |||

We studied the association of diabetes to DES using binominal regression analysis and added in this model variables such as age, gender and BMI. We noted that age (P = 0.01), BMI (P = 0.02) and gender (P = 0.06) were significant confounders.

Discussion

In this series, we noted significantly higher prevalence of chronic metabolic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia and obesity among patients with Dry Eye Syndrome (DES) compared to the rate among adult Saudi population that was published in the literature.

The prevalence of DES in central Saudi Arabia as such is very high26 and the prevalence of metabolic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia and obesity among Saudi adults is also very high.27, 28, 29, 30 Therefore, higher rates of chronic diseases among patients with DES noted in the present study could be a chance of observation. Further studies with larger sample and with comparison group of patients without DES will confirm the findings of our study.

Cicatricle trachoma has been noted to be associated with high prevalence of DES.31, 32 Saudi Arabia was a trachoma endemic country in the past and it is likely that older population with healed trachoma and sequel could also suffer from DES.33

A number of systemic medications are known to exacerbate the symptoms of DES.2 ACE inhibitors used in treatment of hypertension can cause DES.34 Thus, care should be taken in cases of DES to avoid such medication while treating hypertension.

With high prevalence of both DES and chronic metabolic diseases in central Saudi Arabia, it is recommended that inquiry should be periodically made about symptoms of DES in all cases of chronic metabolic syndrome. Patients with DES should be investigated for such metabolic diseases.

DES is common in people having artificial environment (air-conditioned).9 These people are also more likely to have sedentary lifestyle resulting in obesity and other related diseases such as hypertension and diabetes. This could also explain high prevalence of both DES and chronic metabolic syndrome.

The study being a case series type and with a small sample, the interpretation of the subgroup outcomes should be done with caution. The absence of comparison group of patient without DES was a limitation of the study to interpret the association with confidence. The present study could therefore be a pilot and the evidence found in this study could stimulate researchers in Saudi Arabia to further undertake research with better study design and adequate sample size to further study these associations noted among DES and chronic metabolic eye diseases.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank KAMC & NGCSC and their staff for the assistance provided in patients’ assessment and care. We also appreciate the effort of the health information system staff in ensuring data collection and making case records of the past available. In addition, we express our appreciation to the College of Medicine in King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences for their notable support.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Saudi Ophthalmological Society, King Saud University.

References

- 1.Javadi M., Feizi S. Dry eye syndrome. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2011;6(3):192–198. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Ophthalmology. Dry Eye Syndrome PPP – 2013. <https://www.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/dry-eye-syndrome-ppp—2013> [last accessed on 31 Dec 2016].

- 3.Tang Y.L., Cheng Y.L., Ren Y.P., Yu X.N., Shentu X.C. Metabolic syndrome risk factors and dry eye syndrome: a meta-analysis. Int J Ophthalmol. 2016;9(7):1038–1045. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2016.07.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang X., Zhao L., Deng S., Sun X., Wang N. Dry eye syndrome in patients with diabetes mellitus: prevalence, etiology, and clinical characteristics. J Ophthalmol. 2016:2016. doi: 10.1155/2016/8201053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolkoff P. Ocular discomfort by environmental and personal risk factors altering the precorneal tear film. Toxicol Lett. 2010;199(3):203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bukhari A. Etiology of tearing in patients seen in an oculoplastic clinic in Saudi Arabia. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2013;20(3):198–200. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.114790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oriowo O.M. Profile of central corneal thickness in diabetics with and without dry eye in a Saudi population. Optometry. 2009;80(8):442–446. doi: 10.1016/j.optm.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson G.J. The environment and the eye. Eye. 2004;18(12):1235–1250. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iyer J.V., Lee S.Y., Tong L. The dry eye disease activity log study. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:589875. doi: 10.1100/2012/589875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abetz L., Rajagopalan K., Mertzanis P. Impact of Dry Eye on Everyday Life (IDEEL) Study Group. Development and validation of the impact of dry eye on everyday life (IDEEL) questionnaire, a patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measure for the assessment of the burden of dry eye on patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:111. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uchino Y., Uchino M., Dogru M. Changes in dry eye diagnostic status following implementation of revised Japanese dry eye diagnostic criteria. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2012;56:8–13. doi: 10.1007/s10384-011-0099-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alberti KGMM., Zimmet PZ. for the WHO Consultation: Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications Part 1 Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus, provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539–553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Nozha M., Al-Khadra A., Arafah M.R. Metabolic syndrome in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2005;26(12):1918–1925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. BMI Classification in Global Database for Body Mass Index. Last accessed on 31st December 2016. <http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html>.

- 15.Mechanick J.I., Youdim A., Jones D.B. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient—2013 update: cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Obesity. 2013;21(S1):S1–S27. doi: 10.1002/oby.20461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meo S.A. Prevalence and future prediction of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a systematic review of published studies. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66(6):722–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Quwaidhi A.J., Pearce M.S., Sobngwi E., Critchley J.A., O'Flaherty M. Comparison of type 2 diabetes prevalence estimates in Saudi Arabia from a validated Markov model against the International Diabetes Federation and other modelling studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(3):496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2013.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bahijri S.M., Jambi H.A., Al Raddadi R.M., Ferns G., Tuomilehto J. The prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes in the adult population of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia—a community-based survey. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152559. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Nozha M.M., Abdullah M., Arafah M.R., Khalil M.Z., Khan N.B., Al-Mazrou Y.Y. Hypertension in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2007;28(1):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Daghri N.M., Al-Attas O.S., Alokail M.S. Diabetes mellitus type 2 and other chronic non-communicable diseases in the central region, Saudi Arabia (Riyadh cohort 2): a decade of an epidemic. BMC Med. 2011;9:76. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Daghri N.M., Al-Attas O.S., Alokail M.S., Alkharfy K.M., Sabico S.L., Chrousos G.P. Decreasing prevalence of the full metabolic syndrome but a persistently high prevalence of dyslipidemia among adult Arabs. PLoS One. 2010 Aug 13;5(8):e12159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akbar D.H., Ahmed M.M., Al-Mughales J. Thyroid dysfunction and thyroid autoimmunity in Saudi type 2 diabetics. Acta Diabetol. 2006;43(1):14–18. doi: 10.1007/s00592-006-0204-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alsuwaida A.O., Farag Y.M., Al Sayyari A.A., Mousa D., Alhejaili F., Al-Harbi A., Housawi A., Mittal B.V., Singh A.K. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (SEEK-Saudi investigators) - a pilot study. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2010;21(6):1066–1072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-hamoudi W., El-Sabbah M., Ali S. Epidemiological, clinical, and biochemical characteristics of Saudi patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a hospital-based study. Ann Saudi Med. 2012;32(3):288–292. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2012.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al Faleh F., Al Shehri S., Al Ansari S., Al Jeffri M., Al Mazrou Y., Shaffi A. Changing patterns of hepatitis A prevalence within the Saudi population over the last 18 years. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14(48):7371–7375. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.7371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bukhari A., Ajlan R., Alsaggaf H. Prevalence of dry eye in the normal population in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Orbit. 2009;28(6):392–397. doi: 10.3109/01676830903074095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw J.E., Sicree R.A., Zimmet P.Z. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clinic Pract. 2010;87(1):4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saeed AA., Al Hamdan NA. Isolated diastolic hypertension among adults in Saudi Arabia prevalence risk factors predictors and treatment - results of a national survey. Balkan Med J. 2016;33(1):52–57. doi: 10.5152/balkanmedj.2015.153022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al Othaimeen AI., Al Nozha M., Osman AK. Obesity an emerging problem in Saudi Arabia. Analysis of data from the National Nutrition Survey. EMHJ. 2007;13(2):441–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basulaiman M., El Bcheraoui C., Tuffaha M. Hypercholesterolemia and its associated risk factors-Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2013. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24(11):801–808. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucena A., Akaishi P.M., Rodrigues Mde L., Cruz A.A. Upper eyelid entropion and dry eye in cicatricial trachoma without trichiasis. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2012;75(6):420–422. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27492012000600010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tabbara K.F., Bobb A.A. Lacrimal system complications in trachoma. Ophthalmology. 1980;87(4):298–301. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(80)35234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tabbara KF. Trachoma a review. J Chemother (Florence Italy) 2001;13:18–22. doi: 10.1080/1120009x.2001.11782323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalkan Akcay E., Akcay M., Can GD., Aslan N., Uysal BS., Ceran BB. The effect of antihypertensive therapy on dry eye disease. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2015;34(2):117–123. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2014.912660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]