Abstract

Stroke remains the leading cause of death and disability worldwide. This fact highlights the need to search for potential drug targets that can reduce stroke-related brain damage. We showed recently that a glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) inhibitor attenuates tissue plasminogen activator-induced hemorrhagic transformation after permanent focal cerebral ischemia. Here, we examined whether GSK-3β inhibition mitigates early ischemia-reperfusion stroke injury and investigated its potential mechanism of action. We used the rat middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model to mimic transient cerebral ischemia. At 3.5 h after MCAO, cerebral blood flow was restored, and rats were administered DMSO (vehicle, 1% in saline) or GSK-3β inhibitor TWS119 (30 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection. Animals were sacrificed 24 h after MCAO. TWS119 treatment reduced neurologic deficits, brain edema, infarct volume, and blood-brain barrier permeability compared with those in the vehicle group. TWS119 treatment also increased the protein expression of β-catenin and zonula occludens-1 but decreased β-catenin phosphorylation while suppressing the expression of GSK-3β. These results indicate that GSK-3β inhibition protects the blood-brain barrier and attenuates early ischemia-reperfusion stroke injury. This protection may be related to early activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

Keywords: blood-brain barrier, ischemic stroke, Wnt/β-catenin signaling, TWS119

Introduction

Stroke is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide. Thus, identifying potential new drug targets is critical to developing therapies that will reduce stroke-related brain damage. It is known that early disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) contributes to acute cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury1 In recent years, new strategies, such as delayed inhibition of VEGF signaling2, and new drug candidates, such as a novel analog of ginkgolide B (XQ-1H)3 a novel adhesion molecule CEACAM14, orosomucoid5, and lavandula officinalis ethanolic extract6, have been tested for their potential to protect the BBB in ischemic stroke models. Because the results from these studies have been promising, increasing attention is turning toward the identification of potential drug targets to protect the BBB after ischemic stroke.

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is involved in development of the BBB7, and its dysfunction could lead to BBB breakdown in Alzheimer's disease8. Furthermore, activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling enhances neurogenesis and improves neurologic function after focal ischemic injury9. However, the role of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in BBB breakdown and its effects on stroke outcomes are unknown.

Studies have shown that the serine-threonine kinase glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) is involved in the phosphorylation and degradation of β-catenin10, the key molecule of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway11. Therefore, inhibition of GSK-3β may increase the level of β-catenin and further activate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. TWS119, a 4,6-disubstituted pyrrolo-pyrimidine, is a potent inhibitor of GSK-3β12. We have recently shown that TWS119 attenuates tissue plasminogen activator (tPA)-induced hemorrhagic transformation after permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO)13.

In the present study, we used a rat model of transient MCAO to mimic the clinical scenario of acute ischemic stroke, and administered TWS119 to activate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. We hypothesized that GSK-3β inhibition would protect the BBB and reduce early ischemia-reperfusion stroke injury.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All protocols used in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Wuhan University. Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 250-280 g were purchased from Wuhan University Center for Animal Experiments and housed under standard conditions with a 12:12 h light/dark cycle. Food and water were provided to all animals ad libitum. The operators were blinded to the treatment status of the animals in all experiments.

MCAO Model

Focal cerebral ischemia was produced by endovascular occlusion of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) as described previously14-16 Briefly, rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection with pentobarbital sodium (Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Osaka, Japan). Body temperature was maintained at 36.5°C to 37.5°C throughout surgery. After a midline neck incision, the left common carotid artery (CCA) was isolated under a microscope and ligated with a 4-0 silk suture (Ethicon, Issy-Les-Moulineaux, France). The external and internal carotid arteries were temporarily ligated with a 4-0 silk suture. An arteriotomy was performed proximal to the bifurcation of the CCA. A silicone-coated nylon monofilament (40 mm long, 0.26 mm diameter, Beijing Sunbio Biotech, China) was introduced through the arteriotomy and advanced into the internal carotid artery up to a distance of 18-20 mm to occlude the origin of the MCA. At 3.5 hours after this procedure, the rats were reanesthetized, the nylon monofilament was withdrawn to restore MCA blood flow, and TWS119 (30 mg/kg in 1% dimethy sulfoxide, Selleck, Houston, TX, USA)17, 18 or an equal volume of vehicle (DMSO) was administered. After surgery, the rats were returned to their home cages with free access to food and water. A third group of sham control rats underwent the same surgical procedure but the monofilament was not inserted and they were administered only DMSO.

Neurologic Deficit Score

An investigator blinded to the experimental groups performed a neurologic examination of the rats at 24 h after MCAO using a modified version of the scoring system developed by Longa 19: 0, no deficits; 1, difficulty in fully extending the contralateral forelimb; 2, unable to extend the contralateral forelimb; 3, mild circling to the contralateral side; 4, severe circling; 5, falling to the contralateral side. The higher the neurologic deficit score, the more severe the impairment of motor motion.

Brain Water Content

Brain water content was measured with the standard wet-dry ratio method20. Rats were anesthetized and killed by decapitation at 24 h after MCAO. The brains were quickly removed and placed on a dry surface. A 4-mm-thick section of the frontal pole was dissected free before the brain was cut by a brain slicer (Beijing Sunny Instruments Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) and divided into the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres. The two hemisphere slices were packaged in preweighed aluminum foil and immediately weighed on an electronic balance to obtain the wet weight. The hemispheres were then dried for 24 h in an oven at 100°C and reweighed to obtain the dry weight. Brain water content was calculated as a percentage with the following formula: (wet weight - dry weight)/wet weight × 100% 21

Brain Infarct Volume

Infarct volume after MCAO was determined by 2, 3, 5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC, Sigma, Santa Clara, CA) at 24 h after MCAO. Animals were euthanized, and the brains were quickly collected. Brain tissue was sliced into seven coronal sections (2-mm thick) and stained with a 2% solution of TTC at 37°C for 20 min, followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde. TTC stains normal tissue red, but the infarct area remains a pale gray color. TTC-stained sections were photographed, and Image-J image-processing software was used to calculate the infarct volume. The ratio of infarct volume = infarct area of the ipsilateral hemisphere/total area of the ipsilateral hemisphere × 100%22.

Evaluation of BBB Permeability

Evans blue (EB) dye (2%, 3 ml/kg, Sigma) was administered intravenously 3 h before the brain was collected. After being perfused with saline, each hemisphere was weighed and homogenized in 4 ml of 50% trichloroacetic acid solution. The homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000×g for 30 min, and the supernatants were collected and diluted with ethanol (1:3). EB content was determined on a spectrophotometer (Epoch™&Take3™, Biotek, USA) at 620 nm and calculated from a standard curve of EB. EB extravasation was expressed as EB extravasation index (EBI): the ratio of absorbance intensity in the ischemic hemisphere to that in the nonischemic hemisphere23.

Western Blotting

Based on our established protocol24, 25, the total protein were prepared using Cytoplasmic and Nuclear Protein Extraction Kit (Feremants, Shanghai, China) and equal amounts of total protein were separated by Tris-glycine SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk and then incubated with the following primary antibodies overnight at 4°C: (1) rabbit polyclonal anti-GAPDH antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA); (2) rabbit polyclonal anti-β-catenin antibody (1:5000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA); (3) rabbit polyclonal anti-phosphorylated β-catenin (Ser 552) antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA); (4) mouse polyclonal anti-GSK-3β antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology); (5) rabbit polyclonal anti-zonula accludens-1 (ZO-1) antibody (1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA). After incubation with the secondary antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology) for 2 h, membranes were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (10 min each), and the relative density of bands was analyzed on an Odyssey infrared scanner (LICOR Bioscience, Lincoln, NE, USA).

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SD. SPSS for Windows 16.0 software package was used to analyze the data. Differences among groups were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc tests. Student's t-test was used to compare the difference between two groups. Differences were considered significant at P values less than 0.05.

Results

Mortality Rates

Mortality was 0% (0/24) in the sham group, 12.5% (3/24) in the vehicle group, and 4.2% (1/24) in the TWS119 group. Mortality rate was not significantly different among the three groups (P > 0.05).

GSK-3β Inhibition by TWS119 Improved Neurologic Function, Cerebral Edema, and Infarction Volume After Transient MCAO

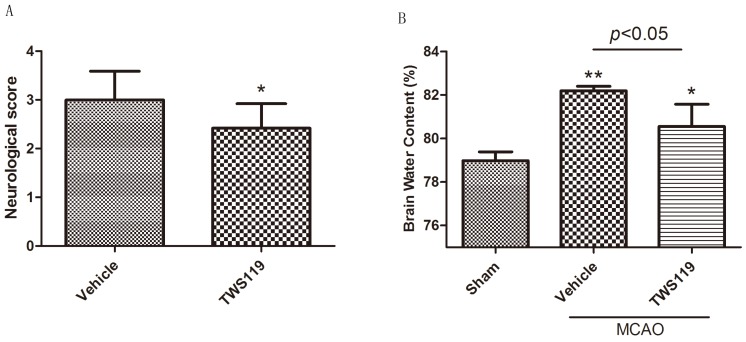

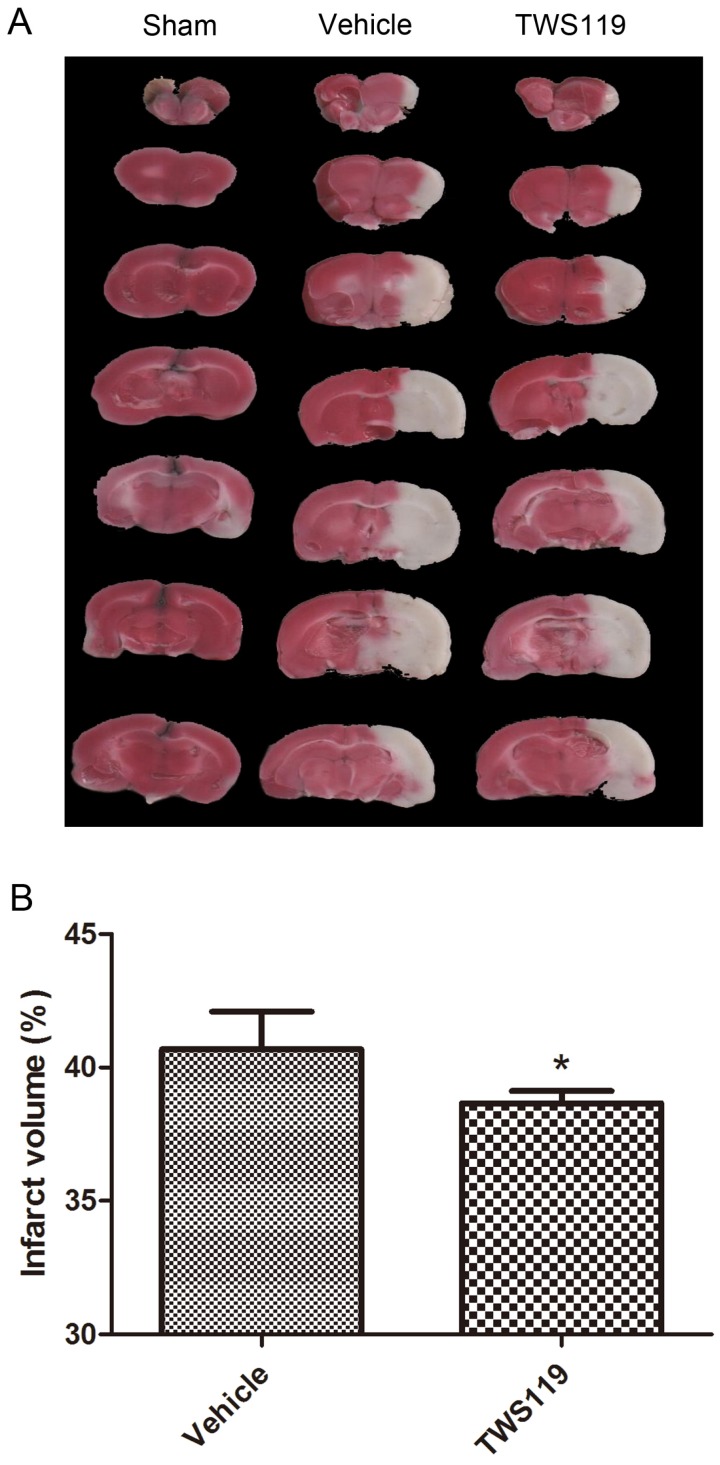

Neurologic deficit, brain water content, and infarct volume were evaluated 24 h after MCAO. TWS119 significantly reduced the neurologic deficit scores compared with those in the vehicle group (n=24 rats/group, P < 0.05; Fig. 1.A). No neurologic deficit was observed in the sham group (data not shown). Similarly, brain water content was lower and infarct volume was smaller in the TWS119-treated group than in the vehicle-treated group (n=6 rats/group, both P<0.05; Figs. 1.B and 2), suggesting that GSK-3β inhibition attenuates brain edema and infarct volume after transient MCAO. The sham group exhibited no cerebral edema or infarction.

Figure 1.

A. Neurologic deficit score at 24 h after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). Rats were treated with vehicle or TWS119 (n=24 rats/group). The data are expressed as means ± SD. *P<0.05 vs. vehicle group. B. Brain water content at 24 h after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). The data are expressed as means ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. sham group.

GSK-3β Inhibition by TWS119 Decreased BBB Permeability After Transient MCAO

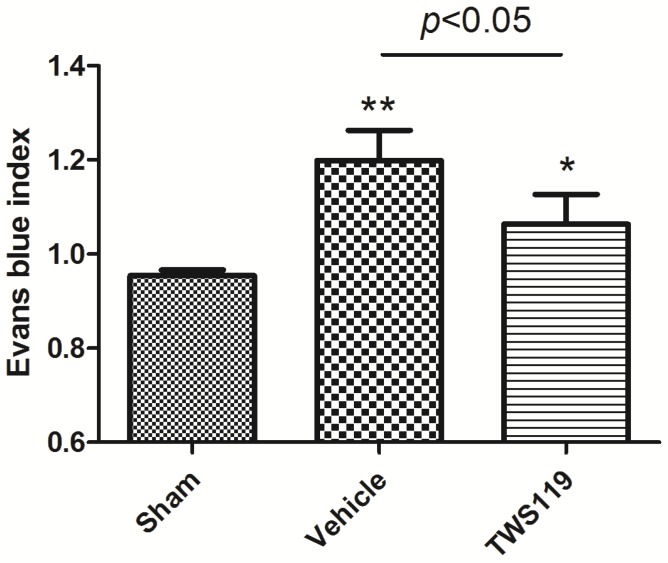

In our study, EB dye leakage was concentrated mainly in the regions of ischemic hemisphere, and BBB leakage was shown with the EBI. We found that EBI of the TWS119-treated group was significantly lower than that of the vehicle-treated group (n=6 rats/group, P<0.05; Fig. 3), indicating that GSK-3β inhibition protects the BBB after transient MCAO.

Figure 3.

Blood-brain barrier permeability as measured by Evans blue leakage at 24 h after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). Rats were treated with vehicle or TWS119 (n=6 rats/group). The Evans blue index (ratio of absorbance intensity in the ischemic hemisphere to that in the nonischemic hemisphere) was used to evaluate blood-brain barrier permeability. The results are expressed as means ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. sham group.

GSK-3β Inhibition by TWS119 Activated the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway and Increased the Expression of ZO-1 After Transient MCAO

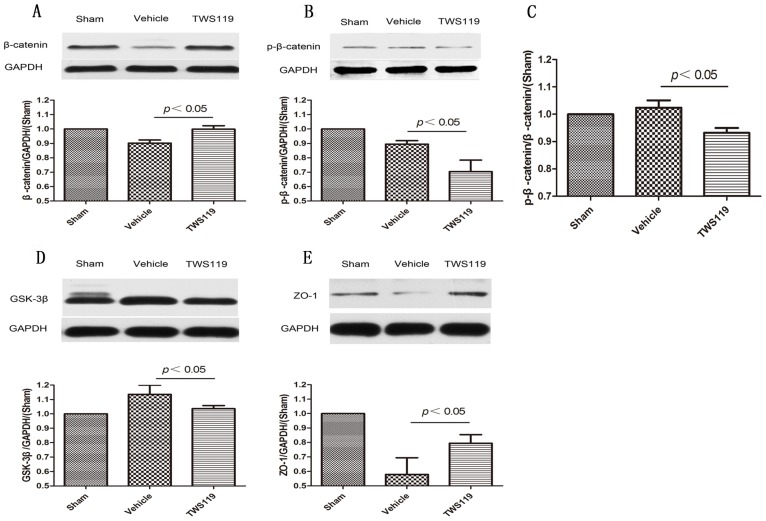

Western blot quantification showed that the total protein expression of β-catenin was upregulated, whereas phosphorylated β-catenin (p-β-catenin) and GSK-3β expression were downregulated in the TWS119-treated group compared with that in the vehicle-treated group (n=6 rats/group, P<0.05; Fig. 4). And the ratio of p-β-catenin to the total β-catenin was reduced significantly after TWS119 treatment(n=6 rats/group, P<0.05; Fig. 4). Additionally, the expression of ZO-1 was significantly higher in the TWS119-treated group than in the vehicle-treated group (n=6 rats/group, P<0.05; Fig. 4). These data indicate that GSK-3β inhibition by TWS119 might activate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which is associated with increased ZO-1 expression and attenuated BBB disruption.

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis of proteins in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and tight junctions of the blood-brain barrier 24 h after transient MCAO (n=6 rats/group). Representative Western blots and densitometric analysis of (A) total β-catenin, (B) phosphorylated β-catenin, (C) The ratio of p-β-catenin to the total β-catenin, (D) GSK-3β and (E) zonula accludens-1 (ZO-1). GAPDH was used as a loading control. The expression of β-catenin and ZO-1 increased in the TWS119-treated group compared to that in the vehicle-treated group. TWS119 treatment reduced the expression of phosphorylated β-catenin and GSK-3β. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments. The results are expressed as means ± SD.

Discussion

In this study, GSK-3β inhibition by TWS119 reduced neurologic deficit score, brain edema, infarct volume, and BBB disruption. This protection was associated with an early activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and an increase in ZO-1 expression. Together, these findings suggest that GSK-3β inhibition by TWS119 attenuates early ischemia-reperfusion injury and protects the BBB.

Ischemic stroke remains a significant health problem worldwide26. Previous studies have shown that thioredoxin27, anfibatide28, and inhibition of CD36-mediated inflammation29 mitigate ischemic stroke injury. Recently, Luo et al.30 demonstrated that interleukin-33 ameliorates ischemic brain injury by promoting Th2 response and suppressing Th17 response. Nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase 1 is another molecule that has exhibited potential neuroprotective effects in vitro and in vivo models of cerebral ischemia31. We have recently shown that GSK-3β inhibitor TWS119 with reported dose and treatment regimen17 attenuates tPA-induced hemorrhagic transformation after permanent focal cerebral ischemia18. Here, we showed that TWS119 reduced early ischemia-reperfusion injury and protected the BBB.

Although many efforts have been made to attenuate ischemic stroke injury, there is no effective therapy that can be used clinically to protect the BBB. The BBB is a key factor that affects acute stroke outcome12 and should be targeted for protection. The European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS)-3 has shown that rtPA alteplase has a safe therapeutic window of 3-4.5 h after the onset of stroke symptoms32. Therefore, in our study, we administered TWS119 at 3.5 h after MCAO and found that it reduced the permeability of the BBB. This finding suggests that TWS119 has a protective effect on the BBB after ischemic stroke, and GSK-3β could be a potential target for brain protection, which was consistent with other studies33, 34.

Previous studies have demonstrated the role of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in the brain's vascular development and BBB formation35. Dickkopf-1, a negative modulator of the Wnt pathway, is involved in the development of ischemic neuronal death36. Growing evidence indicates that Wnt signaling protects the BBB in several brain diseases37. However, the relationship between Wnt/β-catenin signaling and BBB integrity in acute ischemic stroke is still unclear.

To elucidate the underlying mechanisms of action of TWS119, we examined the expression of key proteins in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway as well as tight junction protein ZO-1 at 24 h after MCAO. While suppressing the expression of GSK-3β, TWS119 inhibited phosphorylation of β-catenin and increased its total protein expression38. β-catenin is a key component for activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway39, and phosphorylation at Ser552 has been shown to induce beta-catenin accumulation in the nucleus and increases its transcriptional activity. However, other studies found that the Ser-552 phosphorylation site did not seem important for modulation of β-catenin transcriptional activity40, 41. In our study, we found that β-catenin was upregulated, whereas GSK-3β and p-β-catenin were downregulated in the TWS119-treated group compared with levels in the vehicle-treated group, indicating that TWS119 may activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway by inhibiting GSK-3β expression, reducing p-β-catenin, and enhancing β-catenin expression. The tight junction protein ZO-1 participates in the maintenance of BBB integrity and is the major transmembranal protein of tight junctions in the BBB42. ZO-1 controls angiogenesis and barrier formation43. However, whether Wnt/β-catenin signaling can regulate ZO-1 expression after BBB disruption in ischemic stroke is unknown. Our results showed that in the TWS119-treated group, a reduction in BBB permeability was associated with activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling and upregulation of ZO-1 expression. The sequence of the signaling may need additional research in both in vitro and in vivo models of the BBB.

In summary, our study showed that GSK-3β inhibition with TWS119 protected the BBB and attenuated early ischemia-reperfusion stroke injury. This protection may be related to an early activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and an increase in ZO-1 expression. Thus, the activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling has potential to protect the BBB after ischemic stroke. However, the specific mechanism needs additional research.

Figure 2.

Infarct volume at 24 h after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO). Rats were treated with vehicle or TWS119 (n=6 rats/group). A. Representative TTC-stained, 2-mm coronal brain sections. B. Quantification of the infarct volume in groups that underwent MCAO and treatment with vehicle or TWS119. Infarct volume was calculated as a percentage as follows: infarct area of the ipsilateral hemisphere/total area of the ipsilateral hemisphere × 100%. No infarction was detected in the sham group. The results are expressed as means ± SD. *P<0.05 vs. vehicle group.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81171112, 81371272 to M.C.L., 81372683 to Q.X.C.) and grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01NS078026, R01AT007317 to J. W.).

References

- 1.Takeuchi S, Nagatani K, Otani N, Nawashiro H, Sugawara T, Wada K. et al. Hydrogen improves neurological function through attenuation of blood-brain barrier disruption in spontaneously hypertensive stroke-prone rats. BMC Neurosci. 2015;16:22. doi: 10.1186/s12868-015-0165-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reeson P, Tennant KA, Gerrow K, Wang J, Weiser Novak S, Thompson K. et al. Delayed inhibition of VEGF signaling after stroke attenuates blood-brain barrier breakdown and improves functional recovery in a comorbidity-dependent manner. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2015;35:5128–43. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2810-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang W, Sha L, Kodithuwakku ND, Wei J, Zhang R, Han D. et al. Attenuated Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction by XQ-1H Following Ischemic Stroke in Hyperlipidemic Rats. Molecular neurobiology. 2015;52:162–75. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8851-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiner GM, Ducruet AF. CEACAM1: a novel adhesion molecule that regulates the secretion of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in neutrophils and protects the blood-brain barrier after ischemic stroke. Neurosurgery. 2014;75:N21–2. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000454762.22249.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu L, Jiang Y, Zhu J, Wen Z, Xu X, Xu X. et al. Orosomucoid1: Involved in vascular endothelial growth factor-induced blood-brain barrier leakage after ischemic stroke in mouse. Brain research bulletin. 2014;109:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabiei Z, Rafieian-Kopaei M. Neuroprotective effect of pretreatment with Lavandula officinalis ethanolic extract on blood-brain barrier permeability in a rat stroke model. Asian Pacific journal of tropical medicine. 2014;7:S421–6. doi: 10.1016/S1995-7645(14)60269-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liebner S, Corada M, Bangsow T, Babbage J, Taddei A, Czupalla CJ. et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling controls development of the blood-brain barrier. The Journal of cell biology. 2008;183:409–17. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu L, Wan W, Xia S, Kalionis B, Li Y. Dysfunctional Wnt/beta-catenin signaling contributes to blood-brain barrier breakdown in Alzheimer's disease. Neurochemistry international. 2014;75:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shruster A, Ben-Zur T, Melamed E, Offen D. Wnt signaling enhances neurogenesis and improves neurological function after focal ischemic injury. PloS one. 2012;7:e40843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding S, Wu TY, Brinker A, Peters EC, Hur W, Gray NS. et al. Synthetic small molecules that control stem cell fate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:7632–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0732087100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y, Zheng L, Liu J, Zhou Z, Lv X, Zhang J. et al. [Activation of Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in NK cells by glycogen synthase kinase-3beta inhibitor TWS119 promotes the expression of CD62L] Xi bao yu fen zi mian yi xue za zhi = Chinese journal of cellular and molecular immunology. 2015;31:44–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang W, Li M, Chen Q, Wang J. Hemorrhagic Transformation after Tissue Plasminogen Activator Reperfusion Therapy for Ischemic Stroke: Mechanisms, Models, and Biomarkers. Molecular neurobiology. 2015;52:1572–9. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8952-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang W, Li M, Wang Y, Li Q, Deng G, Wan J. et al. GSK-3beta inhibitor TWS119 attenuates rtPA-induced hemorrhagic transformation and activates the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway after acute ischemic stroke in rats. Molecular neurobiology. 2016;53:7028–36. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9607-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zan L, Zhang X, Xi Y, Wu H, Song Y, Teng G. et al. Src regulates angiogenic factors and vascular permeability after focal cerebral ischemia-reperfusion. Neuroscience. 2014;262:118–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.12.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Xu XL, Zhao D, Pan LN, Huang CW, Guo LJ. et al. TLR3 ligand Poly IC Attenuates Reactive Astrogliosis and Improves Recovery of Rats after Focal Cerebral Ischemia. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics. 2015;21:905–13. doi: 10.1111/cns.12469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang M, Hong X, Chang CF, Li Q, Ma B, Zhang H, Simultaneous detection and separation of hyperacute intracerebral hemorrhage and cerebral ischemia using amide proton transfer MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine; 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gattinoni L, Zhong XS, Palmer DC, Ji Y, Hinrichs CS, Yu Z. et al. Wnt signaling arrests effector T cell differentiation and generates CD8+ memory stem cells. Nat Med. 2009;15:808–13. doi: 10.1038/nm.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang W, Li M, Wang Y, Li Q, Deng G, Wan J, GSK-3beta inhibitor TWS119 attenuates rtPA-induced hemorrhagic transformation and activates the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway after acute ischemic stroke in rats. Molecular neurobiology; 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Yu L, Jiang C, Chen M, Ou C, Wang J. Bone marrow mononuclear cells exert long-term neuroprotection in a rat model of ischemic stroke by promoting arteriogenesis and angiogenesis. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2013;34:56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zan L, Wu H, Jiang J, Zhao S, Song Y, Teng G. et al. Temporal profile of Src, SSeCKS, and angiogenic factors after focal cerebral ischemia: correlations with angiogenesis and cerebral edema. Neurochemistry international. 2011;58:872–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao X, Wu T, Chang CF, Wu H, Han X, Li Q. et al. Toxic role of prostaglandin E2 receptor EP1 after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2015;46:293–310. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J, Liu X, Lu H, Jiang C, Cui X, Yu L. et al. CXCR4(+)CD45(-) BMMNC subpopulation is superior to unfractionated BMMNCs for protection after ischemic stroke in mice. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2015;45:98–108. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang W, Davis CM, Edin ML, Lee CR, Zeldin DC, Alkayed NJ. Role of endothelial soluble epoxide hydrolase in cerebrovascular function and ischemic injury. PloS one. 2013;8:e61244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Yu L, Jiang C, Fu X, Liu X, Wang M. et al. Cerebral ischemia increases bone marrow CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in mice via signals from sympathetic nervous system. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2015;43:172–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu H, Wu T, Hua W, Dong X, Gao Y, Zhao X. et al. PGE2 receptor agonist misoprostol protects brain against intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Neurobiology of aging. 2015;36:1439–50. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borlongan CV. The blood brain barrier in stroke. Curr Pharm Des. 2012;18:3613–4. doi: 10.2174/138161212802002751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang B, Tian S, Wang J, Han F, Zhao L, Wang R. et al. Intraperitoneal administration of thioredoxin decreases brain damage from ischemic stroke. Brain research. 2015;1615:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li TT, Fan ML, Hou SX, Li XY, Barry DM, Jin H. et al. A novel snake venom-derived GPIb antagonist, anfibatide, protects mice from acute experimental ischaemic stroke and reperfusion injury. British journal of pharmacology. 2015;172:3904–16. doi: 10.1111/bph.13178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim EH, Tolhurst AT, Szeto HH, Cho SH. Targeting CD36-mediated inflammation reduces acute brain injury in transient, but not permanent, ischemic stroke. CNS neuroscience & therapeutics. 2015;21:385–91. doi: 10.1111/cns.12326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo Y, Zhou Y, Xiao W, Liang Z, Dai J, Weng X. et al. Interleukin-33 ameliorates ischemic brain injury in experimental stroke through promoting Th2 response and suppressing Th17 response. Brain research. 2015;1597:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang J, Wang P, Wei J, Bao C, Han D. Nicotinamide Mononucleotide Adenylyltransferase 1 Protects Neural Cells Against Ischemic Injury in Primary Cultured Neuronal Cells and Mouse Brain with Ischemic Stroke Through AMP-Activated Protein Kinase Activation. Neurochemical research. 2015;40:1102–10. doi: 10.1007/s11064-015-1569-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Davalos A, Guidetti D. et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. The New England journal of medicine. 2008;359:1317–29. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ajmone-Cat MA, D'Urso MC, di Blasio G, Brignone MS, De Simone R, Minghetti L. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 is part of the molecular machinery regulating the adaptive response to LPS stimulation in microglial cells. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2016;55:225–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin CF, Tsai CC, Huang WC, Wang YC, Tseng PC, Tsai TT. et al. Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3beta and Caspase-2 Mediate Ceramide- and Etoposide-Induced Apoptosis by Regulating the Lysosomal-Mitochondrial Axis. PloS one. 2016;11:e0145460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Artus C, Glacial F, Ganeshamoorthy K, Ziegler N, Godet M, Guilbert T. et al. The Wnt/planar cell polarity signaling pathway contributes to the integrity of tight junctions in brain endothelial cells. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:433–40. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reis M, Liebner S. Wnt signaling in the vasculature. Experimental cell research. 2013;319:1317–23. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polakis P. Formation of the blood-brain barrier: Wnt signaling seals the deal. The Journal of cell biology. 2008;183:371–3. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200810040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou J, Chen Y, Cao C, Chen X, Gao W, Zhang L. Inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta up-regulates beta-catenin and promotes chondrogenesis. Cell and tissue banking. 2015;16:135–42. doi: 10.1007/s10561-014-9449-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ji XK, Xie YK, Zhong JQ, Xu QG, Zeng QQ, Wang Y. et al. GSK-3beta suppresses the proliferation of rat hepatic oval cells through modulating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Acta pharmacologica Sinica. 2015;36:334–42. doi: 10.1038/aps.2014.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taurin S, Sandbo N, Qin Y, Browning D, Dulin NO. Phosphorylation of beta-catenin by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:9971–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508778200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y, Zhu J, Liu Y, Chen X, Lei S, Li L. et al. Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3beta Influences Injury Following Cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion in Rats. International journal of biological sciences. 2016;12:518–31. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.13918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ha TS, Park HY, Seong SB, Ahn HY. Puromycin aminonucleoside increases podocyte permeability by modulating ZO-1 in an oxidative stress-dependent manner. Experimental cell research. 2016;340:139–49. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tornavaca O, Chia M, Dufton N, Almagro LO, Conway DE, Randi AM. et al. ZO-1 controls endothelial adherens junctions, cell-cell tension, angiogenesis, and barrier formation. The Journal of cell biology. 2015;208:821–38. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201404140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]