Abstract

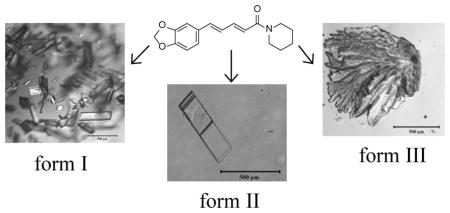

Polymer-induced heteronucleation (PIHn), a powerful crystalline polymorph discovery method, has revealed two novel polymorphs of the low solubility bioenhancer piperine. Both of these forms exhibit enhanced solubility when compared to the commercial polymorph, thereby potentially improving the efficacy of piperine as a bioenhancer. Structural comparison of the three forms reveals that π-π interactions are only present in the two newly discovered forms. Combined with the stability data this reveals that despite the extended conjugation present in the moleculesuch interactions are not preferred in thesolid state.

Keywords: p olymorphism, polymer-induced heteronucleation

Graphical Abstract

Hereinit is shown that piperine, a low solubility bioenhancer, is trimorphic. The twonovel forms discovered possess π-π interactions which are lacking in the commercial form despite the extended conjugation present in the molecule. Furthermore, both of these new forms exhibit enhanced solubility as compared to the commercially utilized polymorph.

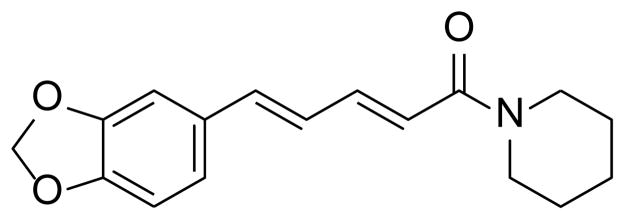

Piperine (1-[5-(1,3-benzodioxol-5-yl)-1-oxo-2,4-pentadienyl]piperidine) is a natural alkaloid that is produced via extraction from both long and black pepper (Figure 1).1,2 Piperine has been used in herbal medicine as an anti-inflammatory, anti-arthritic, and anti-depressant.1–5 Moreover, it has been reported to act as a bioenhancer2, a compound used in combination with a pharmaceutical in order to increase drug bioavailability, in combination with propranolol, theophylline, ciprofloxacin, and tetracycline.2,6–8 Recently, piperine was used as a bioenhancer with the antitubercular drug, rifampicin.2 Rifampicin inhibits transcription within mycobacterium smegmatis by binding to the σ-subunit of RNA polymerase.2 Piperine has been shown to have no effect on mycobacterium smegmatis growth, but when piperine was administered concurrently with rifampicin it was found to increase the binding ability of rifampicin to RNA polymerase.2 The combined therapy of the drug with piperine has enabled the therapeutic dose of rifampicin by 50%. This formulation has been successfully patented and undergone phase I, II, and III clinical trials.2

Figure 1.

Structure of piperine.

Despite its success as a bioenhancer, the aqueous solubility of piperine is only 40 mg/L, which limits its efficacy.1 However, solubility often depends on crystalline form and crystalline polymorphs can exhibit significant differences in solubility and hence, activity within the human body.9 Here the polymorphism of piperine is studied with polymer-induced heteronucleation (PIHn),10–14 a powerful crystalline polymorph discovery method, with the goal of discovering novel crystalline forms that have an enhanced solubility as compared to the known form. Previously, only one crystal form of piperine was known. Herein, it is shown that piperine is at least trimorphic and both new piperine forms exhibit an enhanced aqueous solubility as compared to thepreviously known polymorph.

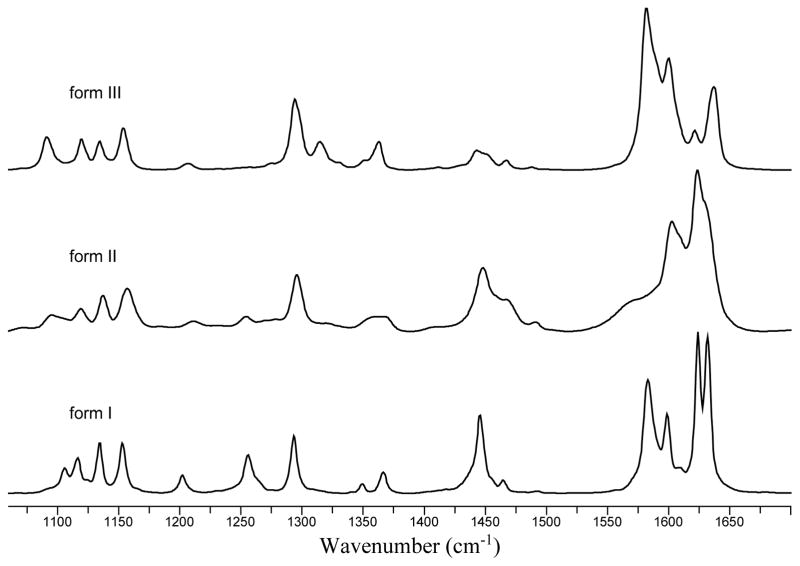

In order to explore the potential polymorphism of piperine, the compound was crystallized by solvent evaporation in the presence of polymer heteronucleants.10–12,15–21 Initial characterization of the piperine polymorphs was carried out by Raman spectroscopy. All of the forms were observed to have characteristic peaks in the 1100–1700 cm−1 region (Figure 2). Strong bands were observed for the aromatic ring vibrations (1583.1, 1591.6, and 1600.4 cm−1 for form I, II, and III respectively) and CH2 bending (1445.8, 1450.7, and 1442.8 cm−1 for form I, II, and III respectively). Additionally, there was significant peak shifting in the 1620–1640 cm−1 region, which can be attributed to the stretching of the amide carbonyl. This region is characterized by at least two peaks for all of the forms with the peak positions of forms II and III shifting towards higher frequencies relative to form I. The shifting of the amide carbonyl vibrational modes gives insight into the expected conformation of the two new forms of piperine as peak shifting can be attributed to local conformational effects and resonance via conjugation of the pentadiene chain. When the carbonyl group is in a planar conformation, electrons are readily donated, thereby shifting the peak observed for the stretching of the amide carbonyl to lower frequencies as observed in form I. It is also possible for this region of the molecule to experience distortions such as local bond rotation, which would hinder the electron donating ability of the nitrogen. In this case, the peaks corresponding to amide carbonyl stretching would shift towards higher energy. Therefore, the Raman data suggests that both forms II and III have increased rotation around either the O=C–N or O=C–C bond.

Figure 2.

Raman spectra of piperine polymorphs: forms I, II, and III.

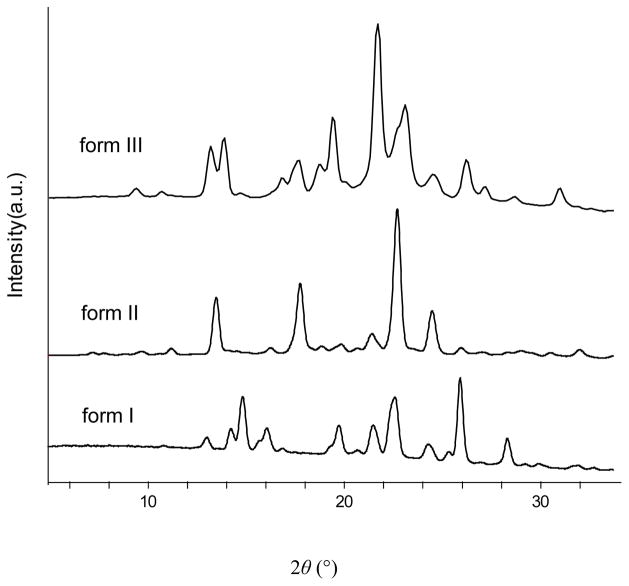

Crystalline samples of all the forms were also characterized by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) (Figure 3). Form I exhibits peaks at 2θ = 13.0°, 14.3°, 14.8°, 16.0°, 19.7°, and 20.7°, which corresponds with the reported literature powder pattern.22 Form II was found to possess peaks at 2θ =13.3°, 13.9°, 16.8°, 19.4°, and 21.7°. Form III was found to be distinct from both forms I and II by the presence of peaks at 2θ = 13.5°, 17.8°, 21.4°, and 22.7°. Thus it was confirmed that forms II and III areunique form s by their distinct powder patterns.

Figure 3.

Powder X-ray diffraction patterns for piperine forms I, II, and III.

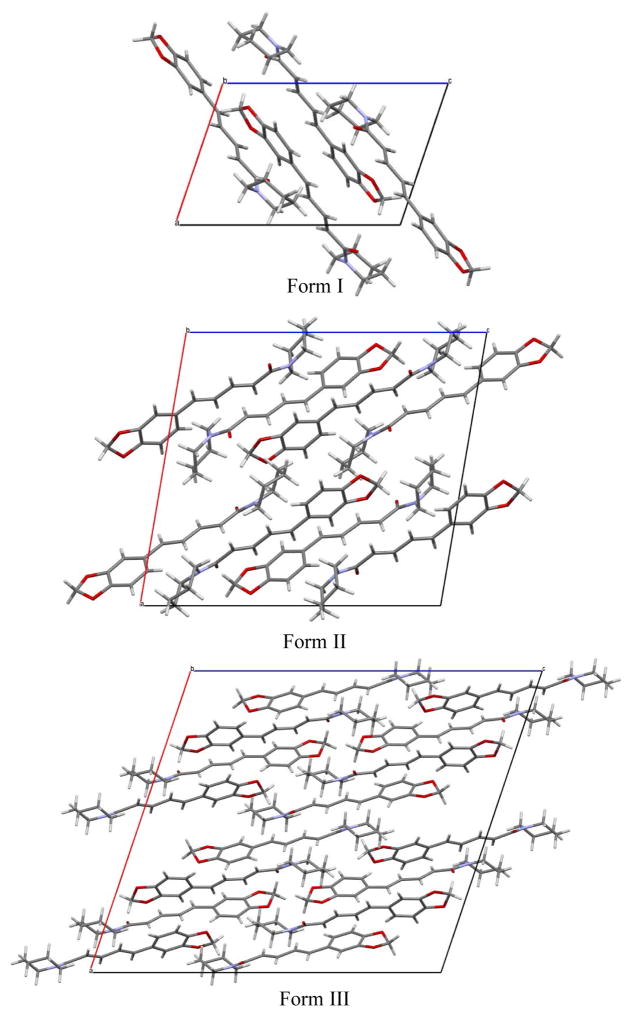

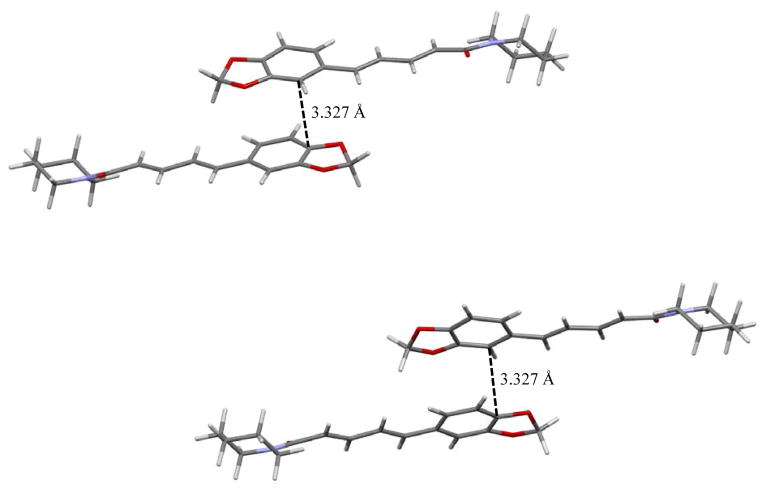

When initially examining the known crystal structure of piperine it was found that it was completely devoid of any π-π interactions despite the extended conjugation present in the molecule.22 It was hypothesized that if alternative arrangements of piperine could be found, they would possess π-π interactions. Single crystal X-ray analysis of form II revealed a monoclinic unit cell in the space group P21/n with the following unit cell parameters: a = 16.6510(2) Å, b = 9.5153(7) Å, c = 18.0362(1) Å, β = 99.587(7)° (see Figure 4, Table 1). The asymmetric unit consists of two symmetry independent molecules with a total of eight molecules within the unit cell. Unlike form I, form II does exhibit π-π interactions with the close contacts at a distance of 3.110 Å and 3.303 Å for each of the molecules in the asymmetric unit (Figure 5). Single crystal X-ray analysis of form III revealed a monoclinic unit cell in the space group C2/c with the following unit cell parameters: a = 23.3983(4) Å, b = 10.0341(2) Å, c = 25.8291(18) Å, β = 108.545(8)° (see Table 1, Figure 4). The asymmetric unit consists of two crystallographically independent molecules with a total of sixteen molecules within the unit cell. In form III the piperidine rings adopt a chair conformation, similar to what is observed in forms I and II. Form III also exhibits π–π interactions with the π–π contacts between the two symmetry independent molecules at a distance of 3.327 Å (Figure 6). Thus, both novel forms exhibit π-π interactions as would be expected in a molecule with extended conjugation.

Figure 4.

Crystal packing diagrams of piperine polymorphs form I, II, and III as viewed down the b-axis.

Table 1.

Crystallographic parameters of piperine forms I, II, and III.

| Form I22 | Form II | Form III | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crystal System | Monoclinic | Monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| Space Group | P21/n | P21/n | C2/c |

| a (Å)= | 8.743(2) | 16.6510(16) | 23.3983(4) |

| b (Å)= | 13.364(3) | 9.5153(7) | 10.0341(2) |

| c (Å)= | 13.147(3) | 18.0362(13) | 25.8291(18) |

| α (°)= | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| β (°)= | 108.66(1) | 99.587(7) | 108.545(8) |

| γ (°) = | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| Volume (Å2) | 1455.36 | 2817.7(4) | 5749.3(4) |

| Z | 4 | 8 | 16 |

| Z′ | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Final R indices (obs data) | 0.056 | 0.0398 | 0.054 |

| Temperature | 283–303 K | 95(2) K | 85(1) K |

Figure 5.

Interactions present in form II showing π stacking close contacts.

Figure 6.

Interactions present in form III showing π stacking close contacts.

To assess the effect of the structural differences on the energies of the polymorphs, the relative free energies were established experimentally for each of the novel forms. The optical absorbance of the piperine polymorphs in water was monitored in situ over time to determine the intrinsic dissolution rate. It is well established that metastable forms exhibit higher solubilities than the thermodynamically stable form.9,23 Accordingly, the intrinsic dissolution rate (IDR) of form I was found to be 0.012 mg/min.cm2, whereas forms II and III were found to exhibit intrinsic dissolution rates of 0.017 mg/min.cm2 and 0.032 mg/min.cm2, respectively (see Supporting Information). Thus, form I was found to be the most thermodynamically stable form within a stability window of 0.56 kcal/mol and form III has a dramatically enhanced solubility compared to the currently administered form(see Supporting Information).

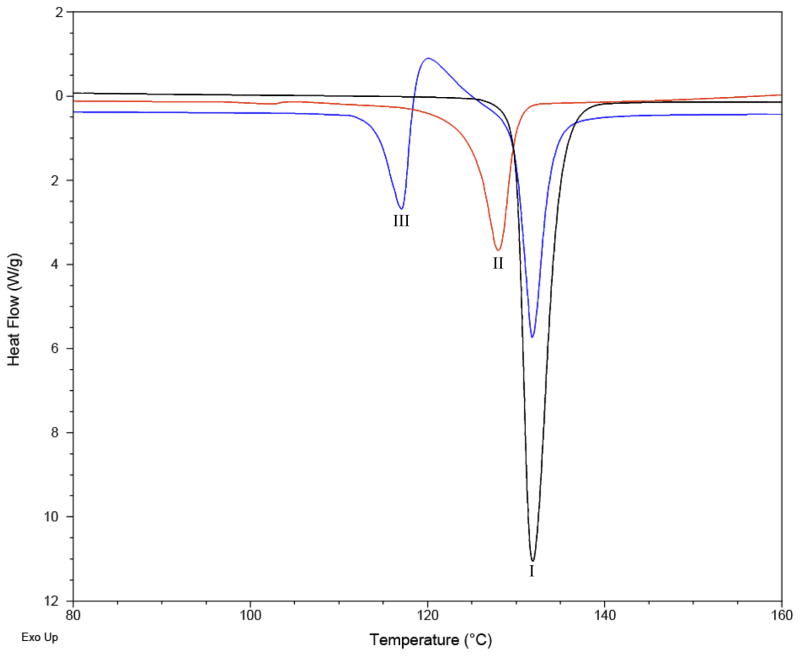

The thermodynamic relationship between polymorphs can be described as enantiotropic or monotropic. If polymorphs are enantiotropically related then the phase transition from one form to another is reversible and the enthalpy change corresponding to this transition is endothermic on heating.23,24 For monotropically related polymorphs, the phase transition from one polymorph to another is irreversible, meaning that only one form is stable at all temperatures and the transformation from a metastable form to the stable form is generally exothermic on heating.23 Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), an analytical technique which can measure the enthalpy associated with events such as melting, can be used to determine if polymorphs are enantiotropes or monotropes. If the higher melting form has the lower melting enthalpy then the forms are enantiotropically related; if the higher melting form has the higher melting enthalpy then the forms are monotropically related. 23,25 Form I was found to melt at 132.49 °C, whereas form II melts at 127.97 °C and form III melts at 116.48 °C; thus form I is the highest melting form. The melting enthalpy of form I (7.5 kcal/mol) is higher than that of form II (6.0 kcal/mol) and form III (5.9 kcal/mol), thus both of the metastable forms are monotropically related to form I (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

DSC scans of piperine forms I, II, and III.

Piperine is at minimum trimorphic. The two novel crystal forms were found to possess π-π interactions, which are lacking in form I despite the extended conjugation in the molecule. Piperine forms II and III have enhanced solubility relative to the commercial form, allowing them to potentially enhance theefficacy of piperine as a bioenhancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant Number RO1 GM106180.

Thanks are extended to Dr. Jeff W. Kampf for single crystal X-ray analysis and funding from NSF grant CHE-0840456for X-ray instrumentation.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Synthesis of polymer libraries, preparation of piperine polymorphs, optical images of all crystalline forms, Raman spectroscopy, powder X-ray diffraction, single crystal X-ray diffraction, differential scanning calorimetry analysis of the piperine polymorphs, and free energy relationships among the piperine polymorphs. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Meghwal M, Goswami TK. Phytother Res. 2013;27:1121. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atal CK, Zutshi U, Rao PG. J Ethnopharmacol. 1981;4:229. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(81)90037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Panahi Y, Badeli R, Karami GR, Sahebkar A. Phytother Res. 2015;29:17. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenshields AL, Doucette CD, Sutton KM, Madera L, Annan H, Yaffe PB, Knickle AF, Dong ZM, Hoskin DW. Cancer Lett. 2015;357:129. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xia Y, Khoi PN, Yoon HJ, Lian S, Joo YE, Chay KO, Kim KK, Jung YD. Mol Cell Biochem. 2015;398:147. doi: 10.1007/s11010-014-2214-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mao QQ, Huang Z, Zhong XM, Xian YF, Ip SP. Behav Brain Res. 2014;261:140. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bano G, Raina RK, Zutshi U, Bedi KL, Johri RK, Sharma SC. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;41:615. doi: 10.1007/BF00314996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mujumdar AM, Dhuley JN, Deshmukh VK, Raman PH, Thorat SL, Naik SR. Indian J Exp Biol. 1990;28:486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernstein J. Polymorphism in Molecular Crystals. Oxford University Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price CP, Grzesiak AL, Matzger AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5512. doi: 10.1021/ja042561m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lopez-Mejias V, Kampf JW, Matzger AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:4554. doi: 10.1021/ja806289a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez-Mejias V, Kampf JW, Matzger AJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:9872. doi: 10.1021/ja302601f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez-Mejias V, Knight JL, Brooks CL, Matzger AJ. Langmuir. 2011;27:7575. doi: 10.1021/la200689a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McClelland AA, Lopez-Mejias V, Matzger AJ, Chen Z. Langmuir. 2011;27:2162. doi: 10.1021/la105067x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curcio E, López-Mejías V, Di Profio G, Fontananova E, Drioli E, Trout BL, Myerson AS. Cryst Growth Des. 2013;14:678. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Profio G, Fontananova E, Curcio E, Drioli E. Cryst Growth Des. 2012;12:3749. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Profio GD, Polino M, Nicoletta FP, Belviso BD, Caliandro R, Fontananova E, Filpo GD, Curcio E, Drioli E. Advanced Functional Materials. 2014;24:1582. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sudha C, Nandhini R, Srinivasan K. Cryst Growth Des. 2014;14:705. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen JH, Shao M, Xiao K, He ZR, Li DW, Lokitz BS, Hensley DK, Kilbey SM, Anthony JE, Keum JK, Rondinone AJ, Lee WY, Hong SY, Bao ZA. Chem Mat. 2013;25:4378. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raina SA, Alonzo DE, Zhang GGZ, Gao Y, Taylor LS. Mol Pharm. 2014;11:3565. doi: 10.1021/mp500333v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Araya-Sibaja AMA, Fandaruff C, Campos CEM, Soldi V, Cardoso SG, Cuffini SL. Scanning. 2013;35:213. doi: 10.1002/sca.21045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grynpas M, Lindley PF. Acta Crystallogr Sect B-Struct Commun. 1975;31:2663. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burger A, Ramberger R. Mikrochim Acta. 1979;2:259. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burger A, Koller KT, Schiermeier WM. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 1996;43:142. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giron D. J Therm Anal. 2001;64:37. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.