Abstract

Purpose of review

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in the world today, and the death rate has remained virtually unchanged in the last twenty years (American Heart Association). This severe life threatening disease underscores a critical need for developing novel therapeutic strategies to effectively treat this devastating disease. Cell-based therapy represents an extremely promising approach. Generation of induced cardiomyocytes (iCMs) directly from fibroblasts offers an attractive novel strategy for in situ heart regeneration. Major challenges of iCM reprogramming include the low conversion rate and heterogeneity of the iCMs. This review will summarize the major advancements in improving the iCM reprogramming efficiency and iCM maturation.

Recent findings

Numerous studies have been published in the past 18 months to describe various strategies for achieving more efficient iCM reprogramming. These strategies are based on our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of cardiogenesis, which include transcriptional networks, signaling pathways, and epigenetic cell fate change.

Summary

Novel strategies for highly efficient iCM reprogramming will be required for applying iCM reprogramming to patients. Creative and combined methods based on our understanding of cardiogenesis will continue to contribute heavily in the advancement of iCM reprogramming. We are highly optimistic that iCM reprogramming based heart therapy will restore the pumping function of damaged patient hearts.

Keywords: Cardiac reprogramming, Cardiogenesis, Cardiac transcriptional networks, Cardiogenesis signaling pathways, Cardiac epigenetic landscape

Introduction

Heart disease is the leading cause of death around the world. After heart injury millions of Cardiomyocytes (CMs) are under irreversible necrosis and infarct area is replaced with fibroblast. Therefore, how to repair injured hearts by regenerative medicine remains as a big challenge. Recently, reprogramming fibroblasts into CM-like cells by introducing three transcription factors GATA4, MEF2C and TBX5 (GMT) has shown therapeutic potential. However, major challenges of iCM reprogramming include the low conversion rate and heterogeneity of the iCMs. To address these challenges, multiple strategies have been reported to improve this novel therapeutic approach. In this review, we summarize the major advancements in improving the iCM reprogramming efficiency and iCM maturation. We discuss the inherent relationship between the reprogramming strategies and our understanding of the basic molecular mechanisms of cardiogenesis. We believe creative and combined approaches based on our knowledge of cardiogenesis will continue to contribute heavily in the advancement of iCM reprogramming. We are highly optimistic that iCM reprogramming based heart therapy may restore the pumping function of damaged patient hearts.

1. Cardiogenesis

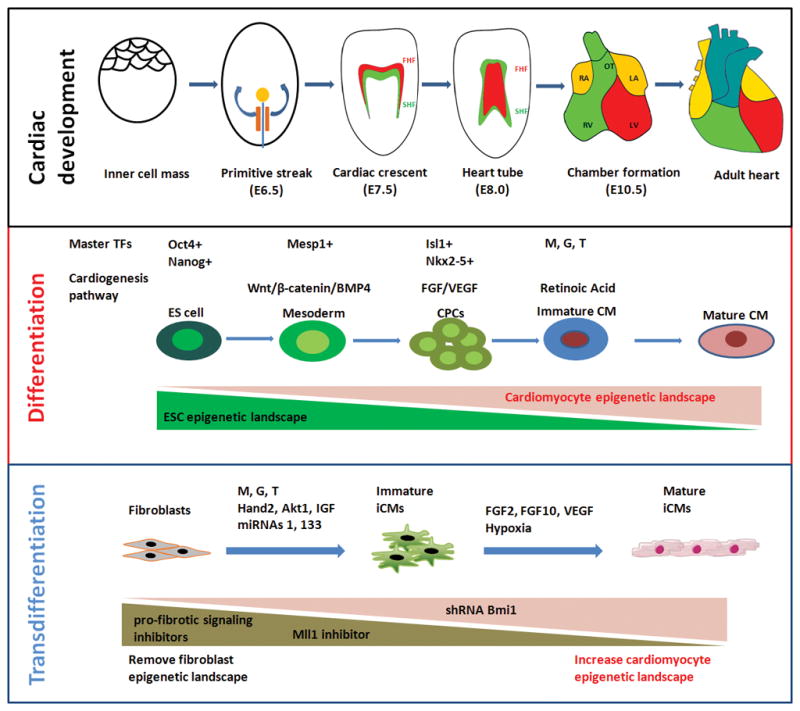

Heart is the first organ to develop during embryogenesis. In mammals, the inner cell mass differentiates into ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm layers after embryo implantation. During gastrulation, the Mesp1+ cells migrate out from the primitive streak to form lateral plate mesoderm and then cardiac crescent, which is composed of first and second heart fields [1]. During late heart tube and chamber formation, cells from the first heart field mainly contribute to left ventricle and part of atria, and cells from the second heart field contribute to right ventricle, outflow tract, and a large percentage of the atria [2] (Fig. 1A). In addition, cells from proepicardial organ and cardiac neural crest also contribute to the heart formation [3,4]. Cardiogenesis is a delicate and dynamic process of cell lineage proliferation and differentiation regulated by a unique set of transcriptional and epigenetic networks and signaling pathways (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

Cardiac development and iCM reprogramming. (A) Major developmental stages during cardiogenesis. FHF, first heart field (red); SHF, second heart field (green), LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium; LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle; OT, outflow tract. FHF cells mainly contribute to LV and part of atria, and SHF cells contribute to RV, OT, and a large percentage of the atria. (B) Cardiac differentiation and (C) cardiac reprogramming mediated by transcription and epigenetic factors, signaling pathways, and dynamic epigenetic landscape changes.

1.1 Cardiac transcriptional network

Cardiogenesis is regulated by a unique cardiac gene network as extensively studied in mice [5]. During development, a number of key cardiac specific genes are upregulated at the precise time windows to progressively initiate the cardiogenesis. Shortly after gastrulation, within the Mesp1+ mesoderm cells, the first cardiac specific TF Nkx2-5 starts to be expressed to initiate cardiogenesis [6]. Following that, GATA4 [7] starts to express at the cardiac crescent and synchronize with Nkx2-5 to further initiate MEF2C [8] expression around E7.5. Around E7.5, other cardiac specific transcription and epigenetic factors, such as Tbx5 [9] and BAF60c [10] also start to express. Importantly, these factors work synergistically and often serve as a co-activator to one another to coordinate cardiac gene expression program. It has been found that Nkx2-5 itself has very limited activating ability, but when cotransfected with GATA4 [7] or Hand2 [11], a synergized effect in cardiac gene activation is observed. Binding of HDAC and Hopx will change the function of GATA4 from promoting cell proliferation to inducing differentiation [12]. A functional physical interaction between TBX5 and MEF2C is also crucial for early heart development and these two factors work synergistically to activate the expression of α-cardiac myosin heavy chain (MYH6) [13]. Chromatin remodeling factor BAF60c regulates the interaction of Brg1 with transcription factors such as Tbx5, Nkx2.5, and Gata4 for cardiac gene expression [10]. Those key transcription and epigenetic factors form the core of a precisely regulated cardiac gene network and plays an essential role in early heart morphogenesis. Ablation of any of these genes leads to severe heart defects in mice and mutations in these genes often lead to congenital heart disease [14].

1.2 cardiogenesis signaling pathways

The development of heart is also tightly regulated by temporal and spatial developmental signals (Fig. 1B). Distinct signal pathways regulate different stage of cardiogenesis. For example, Wnt/beta-catenin [15] is important for the proliferation of cardiac progenitor cells whereas FGF signal is essential for the proliferation of CMs. The knowledge of developmental signals during heart development has greatly benefited the in vitro differentiation of cardiac cells from ESCs/iPSCs (PSCs). Specifically, addition of BMP4 and Wnt3a in PSC culture, which triggers the gastrulation in vivo, induces PSCs to form mesoderm. Another critical step for in vitro cardiac differentiation is the cardiac specification of mesoderm cells. Inhibition of Wnt signals by DDK1 or small molecules which mimics the developmental regulation, greatly increases the differentiation efficiency [16]. Other pathways, such as BMP, FGF, and Notch, can also regulate the cardiac differentiation efficiency by time dependent manner. After CM differentiation, one critical issue is to generate desired subtypes in the adult heart, such as ventricular, atrial, and pacemaker cells. Regulating of developmental signals can guide the CMs to further differentiated into certain subtypes. For example, it has been shown that inhibition of retinoic acid signal increases the ventricular population, whereas addition of retinoic acid increases the atrial populations[17]. A more detailed study of signaling pathways may help generate various cardiac subtypes via transdifferentiation method.

1.3 Changes of epigenetic landscape during cardiogenesis: from mesoderm to cardiomyocytes

In addition to the transcriptional factors and signaling pathways, epigenetic regulation also plays an essential role for the gene regulation during cardiac development. It has been shown that the chromatin structure undergoes progressive changes across genome during differentiation. During cardiac differentiation from ES cells, the pluripotent chromatin landscape is replaced gradually to the CM chromatin landscape (Fig. 1B). In particular, preactivation of chromatin pattern is observed at the promoters of genes associated with heart development in the early stage of differentiation [5,18]. For example, the bivalent histone modification is considered as a open chromatin structure for rapid gene activation [19]. During differentiation, the bivalent histone modification on cardiac genes emerges in mesoderm and cardiac progenitor cells, enables rapid activation of cardiac genes in response to development signals. The increase of chromatin accessibilities in the cardiac genes in mesoderm also contributes to the cardiac differentiation [20]. Major epigenetic factors contribute to these chromatin structural changes are subunit of the BAF complex Baf60c, histone methyltransferase Whsc1, and SmyD1, a SET domain-containing protein [16].

2. Cardiac reprogramming involves key processes in cardiogenesis as well as removal of fibrotic cell identity

2.1 Cardiac transcriptional networks in reprogramming

The initial discoveries in reprogramming to iPSCs, iCMs, and other lineage trans-differentiations show that all key factors required are transcription factors. Therefore, numerous efforts to improve iCM efficiency are focused on identifying extra transcription factors. Indeed, it has been shown that adding Hand2 to GMT combination increases reprogramming efficiency both in vitro and vivo [21–23]. Other factors, such as Nkx2-5 [24], Mesp1 [25], and MyoCD [26] can increase the reprogramming efficiency or improve iCM functions (Fig. 1C). Although multiple combinations have been applied for reprogramming, MEF2C, GATA4 and TBX5 seem to be irreplaceable.

A precise control of gene dosage is required for cardiogenesis and thus, could be required for direct reprogramming, as well. To test the potential effect of gene dosage, one study has taken advantage of the inherent feature of the polycistronic system and generated all possible combinations of G, M, T with identical 2A sequences in a single vector [27]. Their results show that higher protein level of Mef2c combined with lower levels of Gata4 and Tbx5 significantly enhanced reprogramming efficiency compared to separate G, M, T transduction. The optimized gene dosage system also shows 10-fold increase of the number of mature beating iCMs loci. Another interesting observation is that higher protein levels of Gata4 and Tbx5 with a lower level of Mef2c appear to increase the cardiac progenitor cell related gene expression (NppA, NppB) with no increase in the CM related genes expression. These data suggest that high Gata4 and Tbx5 with low Mef2c may induce a CPC like network but not CM network, which is consistent with the observation that GATA4 is more active in CPC stage than in CM stage. The optimized polycistronic vector system was further tested in vivo for iCM reprogramming efficiency after myocardial infarction [28]. As expected, improvement in heart function was observed compared with the traditional separate G, M, and T (G/M/T) delivery. All these studies indicate the important of proper gene dosage in transcriptional gene network for iCM reprogramming.

2.1 Cardiac epigenetic factor networks in reprogramming

In addition to transcription factors, various kind of epigenetic factors are screened and found to enhance reprogramming (Fig. 1C). Interestingly, it has been discovered that MicroRNAs alone can induce or increase cardiac reprogramming. It has been reported that a combination of cardiac specific miRNAs (miRNAs 1, 133, 208, and 499; miR combo) is capable of reprogramming fibroblasts to become cardiac myocyte–like cells both in vitro and in vivo [29,30]. Mechanistically, these miRNAs might induce early reprogramming factor like Nanog [31], as well as improve cardiac reprogramming by directly repressing Snai1 and silencing fibroblast signatures [32]. Indeed, by adding mir-1 and mir-133a to the MGT combination, a higher efficiency of reprogramming has been achieved [33]. It will be interesting to test whether combination of MGT with miRNAs could further improve heart function and cardiac reprogramming efficiency in vivo.

A number of chromatin modify factors that are involved in cardiogenesis can also regulate cardiac reprogramming. BAF60c, a cardiac specific subunit of ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling SWI/SNF complexes, can increase cardio-inducing effect of GATA4, TBX5, and MEF2C [25]. On the other hand, Bmi1, a component of the polycomb complex, plays a protective role in cardiac adult pathophysiology and regulates cardiac reprogramming [34]. When Bmi1 is knockdown, cardiac reprogramming efficiency increases. Our results show that inhibition of Mll1, a H3K4 methyltransferase, can also increase cardiac reprogramming efficiency [35].

2.2 Cardiogenesis signaling pathways in reprogramming

During Cardiogenesis, signaling pathways play an important role. The well-established CMs differentiation protocol from ESCs or iPSCs, requires dynamic signaling activation at different stages. For example, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) 2, FGF10, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) are highly expressed in both developing heart and adult heart and believed to be essential components of the cardiac niches, suggesting that in vivo cardiac niche could enhance reprogramming efficiency [36]. A number of studies have investigated whether cardiac reprogramming can be guided by signaling pathways (Fig. 1C). Beside the early report that VEGF enhances the in vivo cardiac cellular reprogramming efficacy [37], one study shows that a combination of FGF2, FGF10 and VEGF promotes cardiac reprogramming under defined serum-free conditions (FFV medium) and increases spontaneously beating iCMs by 100-fold [38]. Applying the reprogramming medium at later stage of reprogramming (two weeks after transduction) appears most efficient. Moreover, by using FFV medium, functional CMs can be induced by only Mef2c and Tbx5 without Gata4. Interestingly, the exactly medium have been used in the later stage for the differentiation protocol from ESCs or iPSCs to CMs [39]. These two processes might share the same mechanism by facilitate further differentiation of either CPCs or immature CMs into mature CMs.

Recent studies show that certain general expression genes and pathways also could increase the reprogramming efficiency. In one such study, 192 protein kinases are screened and it is observed that constitutively activated Akt/protein kinase B dramatically accelerates and amplifies this process [40]. More importantly, approximately 50% of reprogrammed mouse embryo fibroblasts displayed spontaneous beating after 3 week induction by Akt plus GHMT. Furthermore, addition of Akt1 to GHMT evokes a more mature cardiac phenotype for iCMs. They further reveal that the enhancing effect of Akt is through activation of mTOR and repression of FoxO. Furthermore, IGF1 can also increase reprogramming efficiency through activating Akt pathway.

Another important difference between developing heart and adult heart is that developing heart is in a hypoxia environment. It has been reported that hypoxic pretreatment of newborn mouse dermal fibroblasts for 6 h can improve the efficiency of iCM reprogramming [41]. Especially, a two-fold increase in cardiac troponin I (cTnI) expression and cTnt has been observed. Since myocardial infarction induced heart injury also results in a hypoxic environment in the infarct zone, infarcted heart might facilitate cardiac reprogramming, which is consistent with a better iCM efficiency observed in vivo [21].

2.3 Removal of fibroblast identity and dynamic epigenetic landscape changes during reprogramming

Although cardiac differentiation and cardiac reprogramming may share a similar gene network and regulated by cardiac signaling pathways, these two processes require distinct epigenetic regulation mechanisms (Fig. 1, B&C). A report studying epigenetic dynamics along the reprogramming process shows that H3K27me3 reduces and H3K4me3 increases at cardiac promoters as early as day 3. In contrast, H3K27me3 at loci encoding fibroblast marker genes does not increase until day 10 and H3K4me3 progressively decreases along the reprogramming process [42]. These results imply that reprogramming efficiency can be improved by two strategies. The first strategy is to rapidly remove repressor signature at cardiac promoters and the second strategy is to remove active signature at the fibro gene promoters (Fig. 1C).

Removal of repressor signature at cardiac promoters is exemplified by a Bmi1 knockdown study. By shRNA screen, it has been discovered that shRNA knockdown of Bmi1, a polycomb complex component, significantly enhances induction of beating iCMs from neonatal and adult mouse fibroblasts [34]. Reduced Bmi1 expression corresponds with increased levels of the active histone mark H3K4me3 and reduced levels of repressive H2AK199ub at cardiogenic loci. It appears that shRNA knockdown of Bmi1 also renders GATA4 dispensable. In addition, inhibitors of EZH2 methyltransferase and G9a histone methyltransferase also improve reprogramming efficiency by removing repressor signature at cardiac promoters [43].

The strategy that removing activate signature at the fibrotic gene promoters to improve iCM efficiency has been supported by a recent study as well [33]. By targeting pro-fibrotic signaling using transforming growth factor-β or Rho-associated kinase pathway inhibitor, the efficiency of converting embryonic fibroblasts into functional CM-like cells increases up to 60% [33]. Spontaneously contracting cardiomyocytes emerge in less than 2 weeks, as opposed to 4 weeks with GHMT alone. Although, change of histone marks in fibrotic gene promoter was not tested directly, the pro-fibrotic signaling network has been attenuated by the inhibitor.

Our lab also attempts to identify small molecules that could potentiate the reprogramming ability towards cardiac fate by removing inhibitory roadblocks. We have screened 47 cardiac development related epigenetic and transcription factors and identified an unexpected role of H3K4 methyltransferase Mll1 in inhibiting iCM reprogramming. We have also applied small molecules to target Mll1 activity and observed an improved efficiency in converting embryonic fibroblasts and cardiac fibroblasts into functional CM-like cells. We further reveal that these inhibitors not only inhibit fibroblast genes, but also directly suppress the expression of Mll1 target genes Ebf1 involved in adipocyte differentiation. Our preliminary results imply that in addition to inhibiting fibroblast gene signature, inhibiting other non-cardiac lineage gene signature can also increase the reprogramming efficiency [35].

3. Chemical iCM reprogramming and induced cardiac progenitor cell reprogramming

In addition to the MGT based cardiac reprogramming discussed above, a number of other strategies of cardiac reprogramming have been reported. Pure chemical induced reprogramming is an attractive strategy and has been reported in iPSC reprogramming [44]. Using a very similar small molecule combination to iPSC reprogramming (CRFVPTZ (C, CHIR99021; R, RepSox; F, Forskolin; V, VPA; P, Parnate; T, TTNPB; and Z, DZnep)) with cardiac differentiation medium, beating CMs appear to be induced from mouse fibroblasts [45]. Further studies show the chemical induced iCMs pass through a cardiac progenitor stage instead of a pluripotent stage. More recently, another group reports the successful reprogramming of human fibroblasts into CMs with 9 small molecules (CHIR99021, A83-01, BIX01294, AS8351, SC1, Y27632, OAC2, SU16F and JNJ10198409) [46]. Again, the generated iCMs pass through embryonic progenitor cell stage. Interestingly, both combinations contain two common types of inhibitors, GSK3 inhibitor (CHIR99021) and TGFβ inhibitors (A83-01 and RepSox). TGFβ inhibitors are able to increase GHMT induced cardiac reprogramming [33]. More importantly, CHIR99021 activates wnt3a pathway and promotes cardiac mesoderm lineage commitment during differentiation.

Other cardiac cells have been the targets for reprogramming besides cardiomyocytes. It has been shown that human fibroblast can be reprogrammed into cardiac progenitor cell with Mesp1 and ETS2 [47]. Recently, a report shows that a combination of cardiac factors (Mesp1, Tbx5, Gata4, Nkx2-5 and Baf60c) and signaling molecules (LIF and Bio) can reprogram adult mouse fibroblasts into expandable induced cardiac progenitor cells (iCPCs) [48]. Interestingly, the combination is very similar to CM reprogramming combination except without Mef2C. Using iPSC reprogramming factors to convert fibroblasts into CPCs have been reported as well [49].

4. Conclusion

In summary, cardiac reprogramming is a promising strategy for heart therapy and significant progress has been made in the past two years to increase the efficiency and function of iCMs. In the near future, we anticipate continued progress in basic mechanistic studies to provide new directions for reprogramming. Applying cutting-edge technologies, such as single-cell based genome-wide gene expression and chromatin assays and Cas9 based genome editing technology, will push the field forward. We are particularly intrigued by the discoveries in epigenetic field that removing epigenetic barriers can greatly increase the reprogramming efficiency and iCM maturation. More potent reprogramming factors, including TFs, epigenetic factors and lncRNAs will be identified and an optimized combination will produce mature and functional iCMs with high efficiency. We also expect that with the identification of signaling and small molecules in promoting iCM reprogramming, a much efficient reprogramming culture medium can be developed. It will precisely control cardiac reprogramming at different stages with different conditions. To translate the iCM strategy into clinical studies, a shifted focus on human cell reprogramming and novel approaches for in vivo studies should be considered. Although the virus based gene introduction strategy has some advantages for long-term stable gene expression, the disadvantage of virus integration is a big concern for potential tumorigenesis. Alternative non-Integrated strategies, such as mRNA or protein mediated reprogramming should be thoroughly investigated.

Key points.

Cardiac reprogramming involves key processes in cardiogenesis as well as removal of fibrotic cell identity.

Highly efficient cardiac reprogramming requires activation of key integrated cardiac transcriptional networks.

Functional cardiac reprogramming also requires the reactivation of core cardiogenesis signaling pathways.

Removal of fibrotic cell identity, a unique epigenetic event in reprogramming, is crucial for cardiac reprogramming.

Acknowledgments

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by NIH Grant HL109054, an Inaugural Grant from the Frankel Cardiovascular Research Center of Univeristy of Michigan, and a Pilot Grant from the Joint Institute of University of Michigan Health System and Peking University Health Science Center to Z. Wang.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

- 1.Saga Y, Miyagawa-Tomita S, Takagi A, Kitajima S, Miyazaki J, et al. MesP1 is expressed in the heart precursor cells and required for the formation of a single heart tube. Development. 1999;126:3437–3447. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.15.3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lescroart F, Chabab S, Lin X, Rulands S, Paulissen C, et al. Early lineage restriction in temporally distinct populations of Mesp1 progenitors during mammalian heart development. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:829–840. doi: 10.1038/ncb3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tandon P, Miteva YV, Kuchenbrod LM, Cristea IM, Conlon FL. Tcf21 regulates the specification and maturation of proepicardial cells. Development. 2013;140:2409–2421. doi: 10.1242/dev.093385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farrell M, Waldo K, Li YX, Kirby ML. A novel role for cardiac neural crest in heart development. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1999;9:214–220. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(00)00023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wamstad JA, Alexander JM, Truty RM, Shrikumar A, Li F, et al. Dynamic and coordinated epigenetic regulation of developmental transitions in the cardiac lineage. Cell. 2012;151:206–220. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akazawa H, Komuro I. Cardiac transcription factor Csx/Nkx2-5: Its role in cardiac development and diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;107:252–268. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee Y, Shioi T, Kasahara H, Jobe SM, Wiese RJ, et al. The cardiac tissue-restricted homeobox protein Csx/Nkx2.5 physically associates with the zinc finger protein GATA4 and cooperatively activates atrial natriuretic factor gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3120–3129. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vincentz JW, Barnes RM, Firulli BA, Conway SJ, Firulli AB. Cooperative interaction of Nkx2.5 and Mef2c transcription factors during heart development. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:3809–3819. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeuchi JK, Ohgi M, Koshiba-Takeuchi K, Shiratori H, Sakaki I, et al. Tbx5 specifies the left/right ventricles and ventricular septum position during cardiogenesis. Development. 2003;130:5953–5964. doi: 10.1242/dev.00797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lei I, Liu L, Sham MH, Wang Z. SWI/SNF in cardiac progenitor cell differentiation. J Cell Biochem. 2013;114:2437–2445. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thattaliyath BD, Firulli BA, Firulli AB. The basic-helix-loop-helix transcription factor HAND2 directly regulates transcription of the atrial naturetic peptide gene. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:1335–1344. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trivedi CM, Zhu W, Wang Q, Jia C, Kee HJ, et al. Hopx and Hdac2 interact to modulate Gata4 acetylation and embryonic cardiac myocyte proliferation. Dev Cell. 2010;19:450–459. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosh TK, Song FF, Packham EA, Buxton S, Robinson TE, et al. Physical interaction between TBX5 and MEF2C is required for early heart development. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2205–2218. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01923-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Payne RM, Johnson MC, Grant JW, Strauss AW. Toward a molecular understanding of congenital heart disease. Circulation. 1995;91:494–504. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.2.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gessert S, Kuhl M. The multiple phases and faces of wnt signaling during cardiac differentiation and development. Circ Res. 2010;107:186–199. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.221531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burridge PW, Sharma A, Wu JC. Genetic and Epigenetic Regulation of Human Cardiac Reprogramming and Differentiation in Regenerative Medicine. Annu Rev Genet. 2015;49:461–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-112414-054911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Q, Jiang J, Han P, Yuan Q, Zhang J, et al. Direct differentiation of atrial and ventricular myocytes from human embryonic stem cells by alternating retinoid signals. Cell Res. 2011;21:579–587. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paige SL, Thomas S, Stoick-Cooper CL, Wang H, Maves L, et al. A temporal chromatin signature in human embryonic stem cells identifies regulators of cardiac development. Cell. 2012;151:221–232. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LeGouy E, Thompson EM, Muchardt C, Renard JP. Differential preimplantation regulation of two mouse homologues of the yeast SWI2 protein. Dev Dyn. 1998;212:38–48. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199805)212:1<38::AID-AJA4>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stergachis AB, Neph S, Reynolds A, Humbert R, Miller B, et al. Developmental fate and cellular maturity encoded in human regulatory DNA landscapes. Cell. 2013;154:888–903. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qian L, Huang Y, Spencer CI, Foley A, Vedantham V, et al. In vivo reprogramming of murine cardiac fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes. Nature. 2012;485:593–598. doi: 10.1038/nature11044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song K, Nam YJ, Luo X, Qi X, Tan W, et al. Heart repair by reprogramming non-myocytes with cardiac transcription factors. Nature. 2012;485:599–604. doi: 10.1038/nature11139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ieda M, Fu JD, Delgado-Olguin P, Vedantham V, Hayashi Y, et al. Direct reprogramming of fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by defined factors. Cell. 2010;142:375–386. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Addis RC, Ifkovits JL, Pinto F, Kellam LD, Esteso P, et al. Optimization of direct fibroblast reprogramming to cardiomyocytes using calcium activity as a functional measure of success. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;60:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christoforou N, Chellappan M, Adler AF, Kirkton RD, Wu T, et al. Transcription factors MYOCD, SRF, Mesp1 and SMARCD3 enhance the cardio-inducing effect of GATA4, TBX5, and MEF2C during direct cellular reprogramming. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fu JD, Stone NR, Liu L, Spencer CI, Qian L, et al. Direct reprogramming of human fibroblasts toward a cardiomyocyte-like state. Stem Cell Reports. 2013;1:235–247. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27▪▪.Wang L, Liu Z, Yin C, Asfour H, Chen O, et al. Stoichiometry of Gata4, Mef2c, and Tbx5 influences the efficiency and quality of induced cardiac myocyte reprogramming. Circ Res. 2015;116:237–244. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305547. This study shows that a higher protein level of Mef2c with lower levels of Gata4 and Tbx5 significantly enhanced reprogramming efficiency in culture. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28▪▪.Ma H, Wang L, Yin C, Liu J, Qian L. In vivo cardiac reprogramming using an optimal single polycistronic construct. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;108:217–219. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv223. This study shows that a higher protein level of Mef2c with lower levels of Gata4 and Tbx5 significantly enhanced reprogramming efficiency in vivo. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29▪.Jayawardena TM, Finch EA, Zhang L, Zhang H, Hodgkinson CP, et al. MicroRNA induced cardiac reprogramming in vivo: evidence for mature cardiac myocytes and improved cardiac function. Circ Res. 2015;116:418–424. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304510. This study further demonstrates that microRNAs can induce mature cardiomyocyte-like cells in vivo and suggests miRNA-mediated reprogramming as a therapeutic approach can be used to restore heart function after heart injury. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jayawardena TM, Egemnazarov B, Finch EA, Zhang L, Payne JA, et al. MicroRNA-mediated in vitro and in vivo direct reprogramming of cardiac fibroblasts to cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2012;110:1465–1473. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.269035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31▪.Wang X, Hodgkinson CP, Lu K, Payne AJ, Pratt RE, et al. Selenium Augments microRNA Directed Reprogramming of Fibroblasts to Cardiomyocytes via Nanog. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23017. doi: 10.1038/srep23017. In this research article, the authors show that the microRNA directed Reprogramming can be significantly enhanced by a reprogramming medium that can reactivate pluripotency markers Nanog, Oct4, Sox2, and Klf4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32▪.Muraoka N, Yamakawa H, Miyamoto K, Sadahiro T, Umei T, et al. MiR-133 promotes cardiac reprogramming by directly repressing Snai1 and silencing fibroblast signatures. EMBO J. 2014;33:1565–1581. doi: 10.15252/embj.201387605. This study reveals that miR-133/Snai1 mediated inhibitioin of fibroblast signatures significantly increases cardiac reprogramming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33▪▪.Zhao Y, Londono P, Cao Y, Sharpe EJ, Proenza C, et al. High-efficiency reprogramming of fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes requires suppression of pro-fibrotic signalling. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8243. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9243. This work shows that pro-fibrotic signalling effectively inhibits cardiac reprogramming and supression of pro-fibrotic signalling dramatically enhances the efficiency and kinetics of cardiac reprogramming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34▪▪.Zhou Y, Wang L, Vaseghi HR, Liu Z, Lu R, et al. Bmi1 Is a Key Epigenetic Barrier to Direct Cardiac Reprogramming. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:382–395. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.02.003. This research shows that shRNA knockdown of Bmi1 significantly enhances induction of beating iCMs from neonatal and adult mouse fibroblasts. Furthermore, knockdown Bmi1 can redender GATA4 despensable for reprogramming. Thus, this study identifies Bmi1 as a critical epigenetic barrier to iCM production. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35▪▪.Liu Liu I, Hacer Karatas, Li Yangbing, Wang Li, Gnatovskiy Leonid, Dou Yali, Wang Shaomeng, Qian Li, Wang Zhong. Targeting Mll1 H3K4 methyltransferase activity to guide cardiac lineage specific reprogramming of fibroblasts. 2016 doi: 10.1038/celldisc.2016.36. submitted Our results imply that in addition to inhibiting fibroblast gene signature, inhibiting other non-cardiac lineage gene signature can also increase the reprogramming efficiency. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palazzolo G, Quattrocelli M, Toelen J, Dominici R, Anastasia L, et al. Cardiac Niche Influences the Direct Reprogramming of Canine Fibroblasts into Cardiomyocyte-Like Cells. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:4969430. doi: 10.1155/2016/4969430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathison M, Gersch RP, Nasser A, Lilo S, Korman M, et al. In vivo cardiac cellular reprogramming efficacy is enhanced by angiogenic preconditioning of the infarcted myocardium with vascular endothelial growth factor. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1:e005652. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.005652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38▪▪.Yamakawa H, Muraoka N, Miyamoto K, Sadahiro T, Isomi M, et al. Fibroblast Growth Factors and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Promote Cardiac Reprogramming under Defined Conditions. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;5:1128–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.10.019. In this research article, the author show the combination of FGF2, FGF10, and VEGF promotes cardiac reprogramming under defined serum-free conditions. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kattman SJ, Witty AD, Gagliardi M, Dubois NC, Niapour M, et al. Stage-specific optimization of activin/nodal and BMP signaling promotes cardiac differentiation of mouse and human pluripotent stem cell lines. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:228–240. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40▪▪.Zhou H, Dickson ME, Kim MS, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Akt1/protein kinase B enhances transcriptional reprogramming of fibroblasts to functional cardiomyocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:11864–11869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516237112. In this study, the authors show that the constitutively activated Akt/protein kinase B dramatically accelerates and amplifies cardiac reprogramming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Shi S, Liu H, Meng L. Hypoxia Enhances Direct Reprogramming of Mouse Fibroblasts to Cardiomyocyte-Like Cells. Cell Reprogram. 2016;18:1–7. doi: 10.1089/cell.2015.0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42▪▪.Liu Z, Chen O, Zheng M, Wang L, Zhou Y, et al. Re-patterning of H3K27me3, H3K4me3 and DNA methylation during fibroblast conversion into induced cardiomyocytes. Stem Cell Res. 2016;16:507–518. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2016.02.037. This study shows the epigenetic dynamics reflected by H3K27me3, H3K4me3 and DNA methylation changes during iCM reprogramming and suggests early rapid activation of the cardiac program and later progressive suppression of fibroblast fate at both epigenetic and transcriptional levels. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirai H, Kikyo N. Inhibitors of suppressive histone modification promote direct reprogramming of fibroblasts to cardiomyocyte-like cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;102:188–190. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvu023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hou P, Li Y, Zhang X, Liu C, Guan J, et al. Pluripotent stem cells induced from mouse somatic cells by small-molecule compounds. Science. 2013;341:651–654. doi: 10.1126/science.1239278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45▪.Fu Y, Huang C, Xu X, Gu H, Ye Y, et al. Direct reprogramming of mouse fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes with chemical cocktails. Cell Res. 2015;25:1013–1024. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.99. In this research article, the authors report that cardiomyocyte like cells can be derived from fibroblasts with a chemical cocktail containing CHIR99021, RepSox, Forskolin, VPA, Parnate, and TTNPB. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46▪.Cao N, Huang Y, Zheng J, Spencer CI, Zhang Y, et al. Conversion of human fibroblasts into functional cardiomyocytes by small molecules. Science. 2016;352:1216–1220. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1502. This article reports the reprogramming of human fibroblasts into cardiomyocytes with a cardiac progenitor cell transition stage using nine chemical compounds (CHIR99021, A83-01, BIX01294, AS8351, SC1, Y27632, OAC2, SU16F and JNJ10198409) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Islas JF, Liu Y, Weng KC, Robertson MJ, Zhang S, et al. Transcription factors ETS2 and MESP1 transdifferentiate human dermal fibroblasts into cardiac progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:13016–13021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120299109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48▪▪.Lalit PA, Salick MR, Nelson DO, Squirrell JM, Shafer CM, et al. Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Proliferative Induced Cardiac Progenitor Cells by Defined Factors. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:354–367. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.12.001. This paper reports the reprogramming of fibroblasts into cardiac progenitor cells by 5 cardiac factors (Mesp1, Tbx5, Gata4, Nkx2-5 and Baf60c) in the presence of canonical Wnt and JAK/STAT signaling. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y, Cao N, Huang Y, Spencer CI, Fu JD, et al. Expandable Cardiovascular Progenitor Cells Reprogrammed from Fibroblasts. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18:368–381. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]