Abstract

The current study examined relational aggression as a potential mechanism that explains the association between off-time pubertal development and internalizing problems in youth. Youth gender was also examined as a moderator for the association between these variables. It was hypothesized that early pubertal maturation would be associated with higher levels of relationally aggressive behavior which, in turn, would be associated with elevated levels of internalizing problems. Parents of 372 children between the ages of 8 and 17 were recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Parents responded to demographic information about themselves, as well as information about their child’s pubertal timing, relationally aggressive behavior, and anxiety and depressive symptoms. Findings indicated that early pubertal timing was associated with higher levels of anxiety directly, and higher levels of both anxiety and depressive symptoms indirectly through higher levels of relational aggression. In all but one of the pathways examined, gender was not found to moderate the associations between the study variables of interest. This study is the first to examine relational aggression as a mechanism by which early pubertal timing leads to internalizing problems. The findings suggest that relational aggression could be a target for intervention among early developing youth who are at risk for internalizing problems.

Keywords: pubertal timing, relational aggression, internalizing problems, youth gender, peer stress

Introduction

Puberty is a period of change marked by “rapid and dramatic transformation across virtually all domains of life” including many physical changes such as increases in reproductive hormones (Mendle, 2014, p. 218). These shifts in hormones are typically associated with emotional distress and interact with ongoing neural maturation and prominent changes in social roles and relationships (Mendle, 2014). Although the timing of onset and the progression of pubertal development vary widely within the range of normal development, early physical maturation and accelerated pubertal changes in comparison to one’s peers confers risk for serious problems including internalizing psychopathology (e.g., Caspi, Lynam, Moffitt, & Silva, 1993; Ge, Conger, & Elder Jr., 2001). As these symptoms in youth continue to be a major public health problem (e.g., Kessler et al., 2012; Merikangas et al., 2010), identifying the process by which early pubertal development confers risk for internalizing problems is of substantial importance (e.g., Skoog & Stattin, 2014) and the focus of the current study.

According to the maturation disparity hypothesis (Ge & Natsuaki, 2009), early developing youth are at an increased risk for developing internalizing problems because their social and emotional levels of development lag behind their changes in physical maturation (Ge & Natsuaki, 2009). For example, early maturing youth who stand out among their peers may feel alienated and insecure, leading to difficulty maintaining friendships (Petersen et al., 1991). These individuals may consequently be forced to deal with certain environmental challenges (e.g. negative peer interactions) before they are emotionally or cognitively prepared to do so (Ge et al., 1996), leading to vulnerability to internalizing problems (Rudolph, Troop-Gordon, Lambert, & Natsuaki, 2014; Sontag, Graber, Brooks-Gunn, & Warren, 2008).

Alternatively, the gendered-deviation hypothesis (Sontag, Graber, & Clemans, 2011) contends that the most extreme timing groups within each gender are at greatest risk for symptoms of psychopathology. For girls, breast development is a more physically visible transition than pubertal development among boys (e.g., vocal tone changes, increases in muscle mass) and experiencing this prior to one’s peers may foster a sense of emotional distance (Ge et al., 2001). Therefore, because girls in general tend to experience more visible signs of maturation earlier than boys, early-maturing girls and late-maturing boys are seen as most “deviant” compared to their same age peers (Sontag et al., 2011).

To date, the most consistent findings in the relationship between off-time pubertal development and youth mental health problems are for girls (e.g., Deardorff et al., 2011; Ellis, 2004; Weingarden & Renshaw, 2012). In support of the gendered-deviation and maturation disparity hypotheses, early pubertal timing in girls is consistently associated with symptoms of depression (e.g., Ge et al., 2003; Mendle, Turkheimer & Emery, 2007), anxiety (e.g., Reardon, Leen-Feldner, & Hayward, 2009), and subclinical internalizing problems (e.g., Conley & Rudolph, 2009; Mendle et al., 2007; Smith & Powers, 2009). For boys, although initial work supported the gendered-deviation hypothesis (i.e., late maturing boys display more mental health problems) and suggested that early pubertal onset was potentially even advantageous (Jones & Mussen, 1958; Mussen & Jones, 1957), more recent research supports the maturation disparity hypothesis: Similar to girls, early pubertal maturation is associated with elevated anxiety and depressive symptoms (e.g., Mendle & Ferrero, 2012; Susman & Dorn, 2009). However, these findings for boys have been much less consistent than for girls with studies linking late maturation (Dorn, Susman, & Ponirakis, 2003), early maturation (Ge et al., 2003; Rudolph & Troop-Gordon, 2010), or both (Kaltiala-Heino, Kosunen, & Rimpela, 2003) with internalizing symptoms.

Despite mixed findings in regard to gender differences for direct effects of pubertal timing, a majority of theoretical models (see Ge & Natsuaki, 2009, for a review) delineating the process by which off-time pubertal development confers risk for internalizing psychopathology involve social stress mechanisms for both genders. In particular, some researchers have argued that biological and social changes related to puberty (e.g. growing interest in attracting attention from opposite sex peers) may cause increases specifically in social forms of aggression (Murray-Close et al., 2016). The use of relational aggression, defined as behaviors purposely intended to hurt or manipulate others using relationships as the method of harm (e.g., spreading gossip, socially excluding peers, and using the “silent treatment”) (Crick & Grotpeter, 1995), may increase in early developing youth in response to peer stress (e.g., peer victimization, conflict within close friendships, peer pressure) or in the context of competition for mates (Archer, 2006; Kistner et al., 2010). Supporting this, researchers have found that early pubertal timing is related to increased use of relational aggression both in general (Hemphill et al., 2010; Susman et al., 2007) and in the context of peer stress (Sontag et al., 2011).

Furthermore, engagement in relational aggression has well-established associations with an increased risk for maladjustment (e.g., peer rejection, loneliness) leading to internalizing psychopathology (e.g., Crick, 1996; Murray-Close et al., 2016). Given that problems with peer relationships have been found to be associated with internalizing problems (Laursen, Bukowski, Aunola, & Nurmi, 2007), theorists have suggested that internalizing problems may result from increased use of relational aggression due to these behaviors interfering with the establishment of positive peer relationships (e.g., Kamper & Ostrov, 2013; Murray-Close, Ostrov & Crick, 2007). There has been some evidence suggesting that the association between relational aggression and depressive symptoms is stronger for girls than for boys (Murray-Close et al., 2016). For instance, Crick et al. (1997) reported that relational aggression was associated with depressed affect for girls, but not boys, during early childhood.

The Current Study and Hypotheses

When children physically develop earlier than their peers, it may cause problems within their social interactions (e.g., relational aggression), which in turn leads to increases in internalizing problems. Despite the evidence indicating that early pubertal development is related to relational aggression (Hemphill et al., 2010; Sontag et al., 2011; Susman et al., 2007) and that relational aggression is related to internalizing problems (Crick, 1996; see Murray-Close et al., 2016, for a review), no studies to date have examined relational aggression as a mechanism by which off-time pubertal development confers risk for internalizing problems. Given this gap and the continuing need to identify mechanisms and specificity for effects (i.e., gender differences), the current study examined relational aggression as a potential mechanism that explains the association between off-time pubertal development and internalizing problems. Figure 1 displays the conceptual model tested.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

In the present study it was hypothesized that early pubertal maturation would be associated with higher levels of relationally aggressive behavior, which, in turn, would be associated with elevated levels of internalizing problems. Given the mixed evidence in regard to gender differences, competing hypotheses were considered in regard to the role of gender. Based on the maturation disparity hypothesis, both early maturing girls and boys would exhibit increased levels of relational aggression and, in turn, higher levels of internalizing problems. Based on the gendered-deviation hypothesis, early pubertal timing among girls and late pubertal timing among boys would be associated with higher levels of relational aggression which, in turn, would be associated with elevated levels of internalizing problems. Further, given mixed evidence for gender differences in regard to the association between relational aggression and internalizing problems (Murray-Close et al., 2016), youth gender was also examined as a moderator for this association. The current study examined both depressive and anxiety symptoms as key indicators of broadband internalizing problems. Findings from the current study aim to provide an understanding as to why some youth may be at risk for developing internalizing problems and to consider the prevention and intervention implications.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited online through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) as part of a larger study on the assessment of parenting (N = 564). MTurk is currently the dominant crowdsourcing application used in the social sciences (Chandler, Mueller, & Paolacci, 2014) and previous research has convincingly demonstrated that data gathered via crowdsourcing methods are as reliable as those obtained through more traditional methods (e.g., Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011; Casler, Bickel, & Hackett, 2013).

For the current study, 372 parents of children between the ages of 8 and 17 (M = 12.2, SD = 2.94, 46.8% girls) were included in analyses (i.e., children between 3 and 7 were excluded). Parents were on average 38.9 years old (SD = 7.8) with 61% being mothers. Participants were predominately White (78.5%) with an additional 10.5% who identified as Black, 5.7% as Latino, 3.5% as Asian, and 1.1% as American Indian, Alaska Native, or other Pacific Islander. Parents’ education level ranged from obtaining a H.S. degree or GED (12.4%), attending some college (30.9%), earning a college degree (39.8%), to attending at least some graduate school (16.9%). Reported family income ranged from under $50,000 a year to over $100,000 a year with 22.6% making less than $30,000 per year, 15.6% making between $30,000 and $40,000, 11% making between $40,000 and $50,000, 9.9% making between $50,000 and $60,000, 27.1% making between $60,000 and $100,000, and 13.7% making at least $100,000. Parent marital status was organized into three categories with 17.3% reporting being single (not living with a romantic partner), 66.5% being married, and 16.2% being in a cohabiting relationship (living with a romantic partner but not married).

Procedure

All procedures for the study were approved by a university Institutional Review Board (IRB). Parents were consented online before beginning the survey in accordance with the approved IRB procedures. Parents were compensated $4.00 for participation. For families with more than one child in the target age group, one child was randomly selected through a computer algorithm while parents were taking the survey and the measures were asked in reference to that specific child. Throughout the survey, there were ten attention check items placed to ensure accuracy. These questions asked participants to enter a specific response such as “Please select the Almost Never response option” that changed throughout the survey appearing in random order within other survey items. Participants (N = 2) were not included in the study (i.e., their data removed from the dataset) if they had more than one incorrect response to these ten check items to ensure that responses were not random or automated.

Measures

Demographic information

Parents responded to demographic questions about themselves (e.g., parental age, education), their families (e.g., household composition), and the target child’s demographic information (e.g., gender, age, weight and height).

Pubertal timing

Pubertal timing was evaluated by parent report of the child’s pubertal timing relative to those of their same-sex peers. The specific item read: “Compared to your child’s same-sex peers (age-mate peers), when would you say your child began to experience changes due to puberty, including changes in physical development?” This question was measured from 1 (“much earlier than most of his/her peers”) to 5 (“much later than most of his/her peers”). This item is adapted from the pubertal timing item on the Pubertal Development Scale (PDS), which is the most widely used measure of self and parent reported pubertal development (Dorn, 2006; Dorn, Dahl, & Woodward, 2006; Petersen, Crockett, Richards, & Boxer, 1988). This assessment of pubertal timing was transformed into three categories (−1 = early, 0 = on-time, +1 = late).

Relational aggression

The Children’s Social Behavior Scale-Parent Report was used to assess children’s relational aggression (Crick, 1996). This instrument consists of three subscales: relational aggression, physical aggression, and prosocial behavior. Parents rate on a 5-point scale how true each item is for their child. For the current study, only the relational aggression subscale was used. The relational aggression subscale includes five items assessing relationally aggressive behaviors (e.g., “When angry at another kid, my child tries to get other children to stop hanging around with or stop liking the kid.”). Favorable psychometric properties of this instrument have been demonstrated in prior research (e.g., Crick, 1996). In the current study, the reliability of the relational aggression subscale was adequate (α = .78).

Anxiety and depressive symptoms

The Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale Parent report (RCADS-P) – short version (Chorpita & Ebesutani, 2014) was used to assess youth anxiety and depressive symptoms. The RCADS-P is a parent report questionnaire used to assess youth depressive and anxiety symptoms consistent with DSM–IV (APA, 1994) nosology. Strong support for the validity and reliability of the RCADS scale scores has been demonstrated in both clinical (e.g., Chorpita, Moffit, & Gray, 2005) and nonclinical (e.g., Chorpita, Yim, Moffit, Umemoto, & Francis, 2000; Ebesutani et al., 2012) samples. For the parent report version, parents are asked to indicate how often each item applies to their child on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = often, 3 = always). In the current study, the reliability of the anxiety (α = .86) and depression (α = .85) subscales was excellent.

Data Analyses

Preliminary analyses consisted of descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between all study variables. In order to investigate the indirect effect of pubertal timing on youth anxiety and depressive symptoms through relational aggression, multiple linear regression analyses were conducted in SPSS 22 using the computational tool PROCESS (Hayes, 2013). To test the significance of the indirect effect, PROCESS was utilized to calculate a standardized indirect effect parameter and biased-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals. Confidence intervals that do not contain zero are interpreted as a significant indirect effect. Additionally, Preacher and Kelley’s (2011) kappa-squared mediation effect size was calculated using PROCESS. Finally, as is depicted in Figure 1, the moderating effect of youth gender on the three pathways in the model was examined using PROCESS. If significant interactions emerged, figures were created that illustrated the form of the interaction by depicting the regression lines of the association between predictor (i.e., pubertal timing or relational aggression) and outcome (i.e., relational aggression or internalizing problems) separately for boys and girls (Hayes, 2013).

Results

Preliminary analyses

Missing data across all main study variables was 1% and missing completely at random, Little’s MCAR p >.10. Thus, listwise deletion was used for all analyses. Of the current sample, 19.5% of youth experienced pubertal timing that was a little or much earlier than most of their peers (rating of −1), 67.8% of youth experienced pubertal timing at about the same time as their peers (rating of 0), and the remaining 12.7% of youth experienced pubertal timing that was a little or much later than their peers (rating of +1). The mean age of youth was similar across early (M = 12.1, SD = 2.9), on-time (M = 12.2, SD = 3), and late (M = 12.6, SD = 2.7) pubertal timing groups. This distribution is generally consistent with previous work that has assigned categories of early/on time/late pubertal timing to samples (Brooks-Gunn & Warren, 1989; Ge, Conger, & Elder, 2001; Smith & Powers, 2009). Pubertal timing did not significantly differ by youth body mass index-for-age-and-gender percentile, F (2, 365) = .22, p > .10. Thus, youth age and BMI were not considered further as covariates.

Means, standard deviations, ranges, and bivariate correlations for all study variables are included in Table 1. Youth gender was significantly related to anxiety symptoms such that parents reported higher levels of girls’ than boys’ anxiety. Additionally, youth gender was also related to pubertal timing such that girls were more likely to experience early pubertal development. Pubertal timing was significantly related to relational aggression, anxiety, and depression such that early developers had higher levels of all three variables. Lastly, relational aggression, anxiety, and depressive symptoms were all positively related.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among primary variables.

| M (S.D.) | Range | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Youth gender | -- | 0 – 1 | −.13* | −.01 | −.12* | −.003 |

| 2. Pubertal Timing | -- | −1 – 1 | -- | −.16** | −.18** | −.01 |

| 3. Relational aggression | 8.14 (3) | 5 – 18 | -- | .35** | .41** | |

| 4. Anxiety | 4.33 (4.7) | 0 – 32 | -- | .71** | ||

| 5. Depression | 2.75 (3.5) | 0 – 17 | -- |

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01

Primary analyses

First, an indirect effect model was estimated with anxiety symptoms as the outcome variable. Additionally, the moderating effect of youth gender on associations in the anxiety model was tested. Second, an indirect effect model was estimated with depressive symptoms as the outcome variable followed by the inclusion of the moderating effect of youth gender.

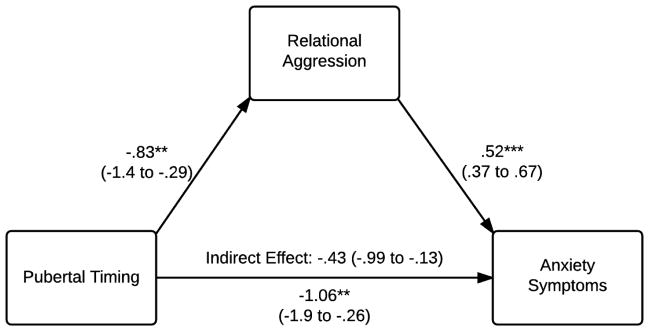

In regard to the anxiety model (See figure 2), pubertal timing was negatively related to relational aggression, b = −.83, CI [−1.4 to −.29], R2 = .16, p < .01, such that early pubertal timing was associated with higher levels of relational aggression. Both pubertal timing, b = −1.06, CI [−1.9 to −.26], p < .01, and relational aggression, b = .52, CI [.37 to .67], p < .001, were significantly related to youth anxiety symptoms, R2 = .38, such that early pubertal timing and higher levels of relational aggression were associated with higher levels of anxiety symptoms. The indirect effect of pubertal timing on youth anxiety symptoms through relational aggression was significant, b = −.43, CI [−.99 to −.13], k2 = .05, CI [.02 to .11]. Youth gender did not further qualify any of the associations in the anxiety model, all interaction ps > .10.

Figure 2.

The direct and indirect effects between pubertal timing, relational aggression, and anxiety symptoms.

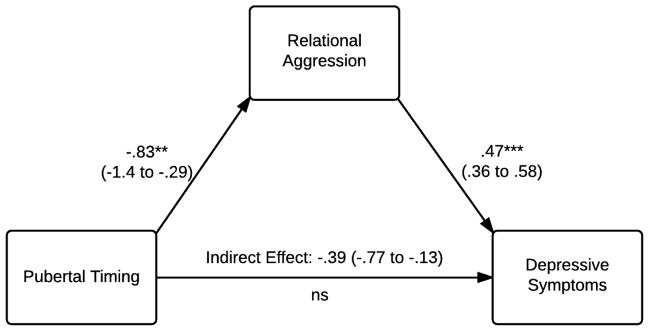

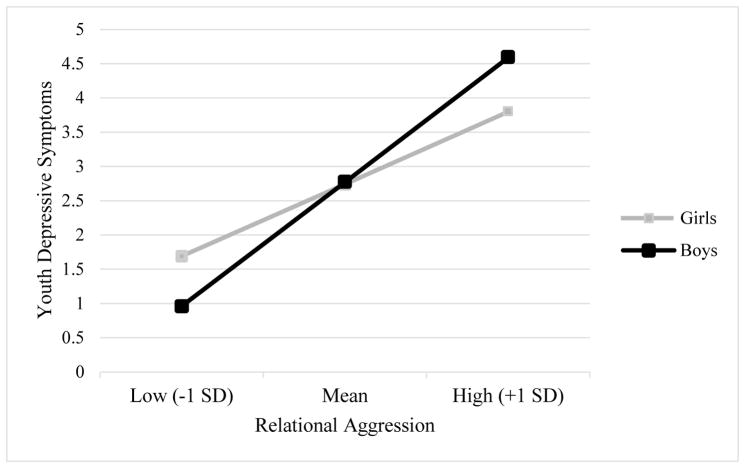

In regard to the depression model (See figure 3), pubertal timing was negatively related to relational aggression, b = −.83, CI [−1.4 to −.29], R2 = .16, p < .01, such that early pubertal timing was associated with higher levels of relational aggression. Relational aggression, b = .47, CI [.36 to .58], p < .001, but not pubertal timing, b = −.18, CI [−.77 to .40], p > .10, was significantly related to youth depressive symptoms, R2 = .41, such that higher levels of relational aggression were associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. The indirect effect of pubertal timing on youth depressive symptoms through relational aggression was significant, b = −.39, CI [−.77 to −.13], k2 = .07, CI [.02 to .13]. Youth gender did not further qualify the association between pubertal timing and relational aggression or youth depressive symptoms, ps > .10. The association between relational aggression and youth depressive symptoms was moderated by youth gender, b = .26, CI [.04 to .48], ΔR2 = .01, p < .05. Follow-up simple slope analyses indicated that higher levels of relational aggression are associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms for both boys, b = .60, CI [.45 to .76], p < .001, and girls, b = .35, CI [.20 to .50], p < .001, but the slope was more significant for boys (see Figure 2).

Figure 3.

The direct and indirect effects between pubertal timing, relational aggression, and depressive symptoms.

Discussion

The goal of the present study was to examine relational aggression as a mechanism by which off-time pubertal development confers risk for anxiety and depressive symptoms. It was hypothesized that early pubertal maturation would be associated with higher levels of relationally aggressive behavior which, in turn, would be associated with elevated levels of internalizing problems. Congruent with study hypotheses and the maturation disparity hypothesis (Ge & Natsuaki, 2009), findings indicated that early pubertal timing was associated with higher levels of anxiety directly and higher levels of both anxiety and depressive symptoms indirectly through higher levels of relational aggression. Further, with one exception (the link between relational aggression and depressive symptoms), results indicated that gender did not moderate the associations between the study variables of interest: Pubertal timing, relational aggression, and internalizing problems.

Prior research has argued that the biological and social changes that occur during puberty may cause increases in social forms of aggression (Murray-Close et al., 2016), such as relational aggression. This may particularly be the case for early developing youth as they are forced to deal with peer challenges before they are prepared to do so (Ge et al., 1996). These youth may engage in relational aggression in the face of these challenges. In turn, engaging in relationally aggressive behaviors may be a risk factor for developing anxiety and depression because these behaviors interfere with the establishment of positive peer relationships (Kamper & Ostrov, 2013). Congruent with earlier research, early pubertal timing in the current study was associated with relational aggression (Hemphill et al., 2010; Sontag et al., 2011) and, in turn, relational aggression was associated with internalizing problems (Crick, 1996; see Murray-Close et al., 2016, for a review). Furthermore, the indirect effect through relational aggression was significant for both anxiety and depressive symptoms.

The current study is the first to demonstrate that relational aggression is one link between early pubertal timing and internalizing problems. Identifying relational aggression as a mechanism by which early pubertal timing is associated with internalizing problems is important in that it suggests a potential target for prevention and intervention programs for these youth. Future research should examine if interventions that specifically target relationally aggressive conduct (See Leff, Waasdorp, & Crick, 2010, for a review) are effective in preventing youth with early pubertal onset from developing internalizing problems. Teaching these youth to deal with peer challenges through the use of adaptive interpersonal skills (e.g., interpreting the intentions of others and generating alternative behaviors to enact) rather than gossip, peer exclusion, or the “silent treatment” may lead to better psychological outcomes. It is important to note that, for anxious symptoms, there was both a direct and indirect link between early pubertal timing and internalizing problems, suggesting that there are other mechanisms besides relational aggression. Future research should explore other potential mechanisms in order to identify additional mechanisms that can be targeted in psychological intervention.

Given the mixed evidence in the literature for gender differences, competing hypotheses (i.e., maturation disparity vs. gendered-deviation) were considered in regard to the role of gender. Our findings support the maturation disparity hypothesis: Both early maturing girls and boys exhibited higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms, operating at least partially through higher levels of relational aggression. In regard to the one exception, gender moderated the association between relational aggression and internalizing problems. Explication of the interaction indicated that higher levels of relational aggression were related to higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms for both boys and girls, but the slope for depressive symptoms was more significant for boys than girls. Therefore, although the results indicate that gender moderates the association between relational aggression and depressive symptoms, the interaction does not appear to be particularly informative.

Limitations

There are several limitations of the current study that should be mentioned. First, as we have noted, the data are cross-sectional, raising questions about the direction of effects and temporal precedence that are better addressed by longitudinal designs. Caution should be used when interpreting causal pathways in the current model, and future research examining similar questions should utilize longitudinal designs. Second, due to the crowdsourcing methodology, all variables in the model were from a single reporter. As this raises the issue of shared method variance, the use of multiple reporters on constructs of interest could strengthen confidence of findings in future work. Further, as the reporter was a parent, youth report on any or all of the constructs may have resulted in different findings.

Despite these limitations, the current study also has notable strengths. First, this is the first study to test and demonstrate that relational aggression is one mechanism for explaining the link between pubertal timing and depression and anxiety. Second, the current study utilized Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to recruit the sample. Although MTurk as utilized in this study was restricted to a single reporter, it does allow the recruitment of a relatively large national sample and yields data that are reliable (e.g., Casler et al., 2013).

In sum, findings indicated that early pubertal timing was indirectly associated with both anxiety and depressive symptoms through relational aggression. Understanding the mechanisms by which early pubertal timing leads to internalizing problems can identify treatment components for an at-risk group of youth: Girls, as well as boys, with early pubertal onset. Replication of the current findings with longitudinal designs, as well as with both youth and parent report, will increase confidence in the conclusions that can be reached.

Figure 4.

The form of the interaction between relational aggression and depressive symptoms for boys and girls.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by the Child and Adolescent Psychology Training and Research, Inc (CAPTR). The second author is supported NICHD grant F31HD082858 and the third author is supported by NIMH grant R01MH100377. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent he official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declares no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding: This study was funded by the Child and Adolescent Psychology Training and Research, Inc (CAPTR). The second author is supported NICHD grant F31HD082858 and the third author is supported by NIMH grant R01MH100377. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent he official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Contributor Information

Hayley Pomerantz, University of Vermont, Burlington VT.

Justin Parent, University of Vermont, Burlington VT.

Rex Forehand, University of Vermont, Burlington VT.

Nicole Lafko Breslend, University of Vermont, Burlington VT.

Jeffrey P. Winer, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst MA

References

- Archer J. Testosterone and human aggression: an evaluation of the challenge hypothesis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2006;30(3):319–345. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6(1):3–5. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casler K, Bickel L, Hackett E. Separate but equal? A comparison of participants and data gathered via Amazon’s MTurk, social media, and face-to-face behavioral testing. Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29(6):2156–2160. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2013.05.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Lynam D, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. Unraveling girls’ delinquency: Biological, dispositional, and contextual contributions to adolescent misbehavior. Developmental Psychology. 1993;29(1):19–30. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.29.1.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler J, Mueller P, Paolacci G. Nonnaïveté among Amazon Mechanical Turk workers: Consequences and solutions for behavioral researchers. Behavior Research Methods. 2014;46(1):112–130. doi: 10.3758/s13428-013-0365-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Ebesutani C. Revised children’s anxiety and depression scale user’s guide. University of California; Los Angeles: 2014. Unpublished Users Guide. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Moffitt CE, Gray J. Psychometric properties of the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale in a clinical sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43(3):309–322. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Yim L, Moffitt C, Umemoto LA, Francis SE. Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: a revised child anxiety and depression scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38(8):835–855. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley CS, Rudolph KD. The emerging sex difference in adolescent depression: Interacting contributions of puberty and peer stress. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21(2):593–620. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR. The role of overt aggression, relational aggression, and prosocial behavior in the prediction of children’s future social adjustment. Child Development. 1996;67(5):2317–2327. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Casas JF, Mosher M. Relational and overt aggression in preschool. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33(4):579–588. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.33.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development. 1995;66(3):710–722. doi: 10.2307/1131945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff J, Ekwaru JP, Kushi LH, Ellis BJ, Greenspan LC, Mirabedi A, … Hiatt RA. Father absence, body mass index, and pubertal timing in girls: Differential effects by family income and ethnicity. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;48(5):441–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn LD. Measuring puberty. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39(5):625–626. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn LD, Dahl RE, Woodward HR, Biro F. Defining the boundaries of early adolescence: A user’s guide to assessing pubertal status and pubertal timing in research with adolescents. Applied Developmental Science. 2006;10(1):30–56. doi: 10.1207/s1532480xads1001_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn LD, Susman EJ, Ponirakis A. Pubertal timing and adolescent adjustment and behavior: Conclusions vary by rater. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2003;32(3):157–167. doi: 10.1023/A:1022590818839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ebesutani C, Reise SP, Chorpita BF, Ale C, Regan J, Young J, … Weisz JR. The Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale-Short Version: Scale reduction via exploratory bifactor modeling of the broad anxiety factor. Psychological Assessment. 2012;24(4):833–845. doi: 10.1037/a0027283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ. Timing of pubertal maturation in girls: An integrated life history approach. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(6):920–958. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH. Coming of age too early: Pubertal influences on girls’ vulnerability to psychological distress. Child Development. 1996;67(6):3386–3400. doi: 10.2307/1131784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH., Jr Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37(3):404–417. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.37.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Kim IJ, Brody GH, Conger RD, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, Cutrona CE. It’s about timing and change: Pubertal transition effects on symptoms of major depression among African American youths. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(3):430–439. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Natsuaki MN. In search of explanations for early pubertal timing effects on developmental psychopathology: Pubertal timing and psychopathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18(6):327–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01661.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hemphill SA, Kotevski A, Herrenkohl TI, Toumbourou JW, Carlin JB, Catalano RF, Patton GC. Pubertal stage and the prevalence of violence and social/relational aggression. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):e298–e305. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MC, Mussen PH. Self-conceptions, motivations, and interpersonal attitudes of early- and late-maturing girls. Child Development. 1958;29:491–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1958.tb04906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltiala-Heino R, Kosunen E, Rimpelä M. Pubertal timing, sexual behaviour and self-reported depression in middle adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 2003;26(5):531–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-1971(03)00053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamper KE, Ostrov JM. Relational aggression in middle childhood predicting adolescent social-psychological adjustment: The role of friendship quality. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42(6):855–862. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.844595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Georgiades K, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Merikangas KR. Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(4):372–380. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistner J, Counts-Allan C, Dunkel S, Drew CH, David-Ferdon C, Lopez C. Sex differences in relational and overt aggression in the late elementary school years. Aggressive Behavior. 2010;36(5):282–291. doi: 10.1002/ab.20350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Bukowski WM, Aunola K, Nurmi J. Friendship moderates prospective associations between social isolation and adjustment problems in young children. Child Development. 2007;78(4):1395–1404. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff SS, Waasdorp TE, Crick NR. A review of existing relational aggression programs: Strengths, limitations, and future directions. School Psychology Review. 2010;39(4):508–535. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J. Why puberty matters for psychopathology. Child Development Perspectives. 2014;8(4):218–222. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J, Ferrero J. Detrimental psychological outcomes associated with pubertal timing in adolescent boys. Developmental Review. 2012;32(1):49–66. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J, Turkheimer E, Emery RE. Detrimental psychological outcomes associated with early pubertal timing in adolescent girls. Developmental Review. 2007;27(2):151–171. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Brody D, Fisher PW, Bourdon K, Koretz DS. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001–2004 NHANES. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):75–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray-Close D, Nelson DA, Ostrov JM, Casas JF, Crick NR. Relational aggression: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In: Cohen D, Cicchetti D, editors. Developmental psychopathology, Genes and environment. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2016. pp. 660–723. [Google Scholar]

- Murray-Close D, Ostrov JM, Crick NR. A short-term longitudinal study of growth of relational aggression during middle childhood: Associations with gender, friendship intimacy, and internalizing problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19(1):187–203. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussen PH, Jones MC. Self-conceptions, motivations, and interpersonal attitudes of late- and early-maturing boys. Child Development. 1957;28:243–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1957.tb05980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrov JM, Massetti GM, Stauffacher K, Godleski SA, Hart KC, Karch KM, … Ries EE. An intervention for relational and physical aggression in early childhood: A preliminary study. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2009;24:15–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2008.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1988;17(2):117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Sarigiani PA, Kennedy RE. Adolescent depression: Why more girls? Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20(2):247–271. doi: 10.1007/BF01537611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Kelley K. Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychological Methods. 2011;16(2):93–115. doi: 10.1037/a0022658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon LE, Leen-Feldner EW, Hayward C. A critical review of the empirical literature on the relation between anxiety and puberty. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29(1):1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KD, Troop-Gordon W, Lambert SF, Natsuaki MN. Long-term consequences of pubertal timing for youth depression: Identifying personal and contextual pathways of risk. Development and Psychopathology. 2014;26(4):1423–1444. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414001126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skoog T, Stattin H. Why and under what contextual conditions do early-maturing girls develop problem behaviors? Child Development Perspectives. 2014;8(3):158–162. doi: 10.1111/cdep.12076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AE, Powers SI. Off-time pubertal timing predicts physiological reactivity to postpuberty interpersonal stress. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19(3):441–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontag LM, Graber JA, Brooks-Gunn J, Warren MP. Coping with social stress: implications for psychopathology in young adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36(8):1159–1174. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9239-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sontag LM, Graber JA, Clemans KH. The role of peer stress and pubertal timing on symptoms of psychopathology during early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40(10):1371–1382. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9620-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susman EJ, Dockray S, Schiefelbein VL, Herwehe S, Heaton JA, Dorn LD. Morningness/eveningness, morning-to-afternoon cortisol ratio, and antisocial behavior problems during puberty. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43(4):811–822. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susman EJ, Dorn LD. Puberty: Its role in development. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology, vol 1: Individual bases of adolescent development. 3. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. pp. 116–151. [Google Scholar]

- Weingarden H, Renshaw KD. Early and late perceived pubertal timing as risk factors for anxiety disorders in adult women. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012;46(11):1524–1529. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]