Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this article was to systematically review the literature to identify the impact of primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) on specific health-related quality of life (HRQoL) domains.

Methods

A meta-analysis was performed, and the related articles were searched in Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, China Biology Medicine, and Web of Science databases and in reference lists of articles and systematic reviews. Score of the Short Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire was used as the outcome measurement, and mean differences (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated.

Results

Seven studies were included, comprising 521 patients with pSS and 9,916 healthy controls. The SF-36 questionnaire score of each domain (physical function, role physical [RP] function, emotional role function, vitality, mental health, social function, body pain, general health, physical component scale, mental component scale) was lower in patients with pSS than in healthy controls, especially the score in the dimension of RP function.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis showed that patients had lower pSS score in each dimension of the SF-36, mostly in the RP function. This demonstrated that targeted interventions should be carried out to improve the HRQoL of pSS patients.

Keywords: primary Sjögren’s syndrome, quality of life, SF-36, meta-analysis

Introduction

Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by a progressive lymphocytic infiltration of the exocrine glands. The salivary and lacrimal glands are most commonly affected, which would lead to the result that the eyes and mouth are in dry conditions. Extraglandular manifestations include arthritis, skin vasculitis, lymphoma, pulmonary disease, and renal disease.1 SS can be primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) or secondary Sjögren’s syndrome (sSS), the latter being associated with other autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. The prevalence of SS is estimated to be ~0.5%–1.0% among the general population, and it is considered as the second most common rheumatic disease.2,3

SS is associated with several psychological disorders, including depression and anxiety;4–6 suicide attempts;7 physical problems such as fatigue,8,9 working disability,10,11 and general discomfort; as well as lowered health-related quality of life (HRQoL).12,13 Because treatment for SS is symptom oriented, individualized management should be aimed at relieving symptoms and improving HRQoL.

HRQoL was defined as the “physical, psychological and social domains of health, seen as distinct areas that are influenced by a person’s experiences, beliefs, expectations and perceptions”.14 Since the last few decades, original studies15–17 and reviews18,19 have reported HRQoL in patients with SS. However, the relative degree of impairment in each domain differed among samples, and it was not obvious which domain of HRQoL was most negatively affected. In this study, our objective was to systematically review the effects of pSS on specific HRQoL aspect compared with the outcomes of healthy controls.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic literature search of Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, CNKI, CBM, and Web of Science databases for identification of articles published (until November 19, 2016) was performed using the terms (“quality of life” [MeSH] OR “health-related quality of life” OR “health status measurement” OR “subjective health status” OR “Quality of Life Questionnaire”) AND (“sjögren’s syndrome” [MeSH] OR “sicca syndrome”). No language restriction was imposed. A manual search was also performed on reference lists of included articles, reviews, editorials, and proceedings of international congresses. The data search and screening of titles, abstracts, and full-text articles were completed independently by two reviewers. Any discrepancy was solved by consultation with a third reviewer.

Eligibility of relevant studies

Studies that reported HRQoL in patients with pSS and healthy controls were considered suitable for our analysis. Studies were excluded if they assessed a single aspect because HRQoL is defined as a multidimensional concept that encompasses physical, emotional, and social aspects associated with a disease or its treatment. Studies that used other extraordinary questionnaires/instruments instead of Short Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire were also excluded. If the outcomes we needed were not reported in the study, the study authors were contacted to ask for additional information. The articles were excluded if additional information was not available. Studies were also rejected if they did not meet the inclusion criteria or if they reported duplicated or useless data.

Data extraction

Information from each study was extracted by two reviewers independently. General characteristics of studies (author, journal, year of publication, design, ethnicity, study size, and number of cases), characteristics of the SS and healthy control groups (selection criteria, age, and duration), methodology (HRQoL measurement method and study quality), and results (mean ± SD) were recorded when available and double checked. If necessary, the data set was completed through communication with the authors. Two reviewers assessed the quality of included studies using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analysis; the NOS depends on “selection, comparability, and exposure” of selected studies. A study can be awarded a maximum of one star for each numbered item within the selection and exposure categories. A maximum of two stars can be given for comparability.20

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

The scores on questionnaires used to evaluate HRQoL in SS patients and controls in each study were extracted as mean differences (MD) ± SD. MD and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for scores in each study eligible for the meta-analysis and combined by using fixed- or random-effects model according to DerSimonian and Laird.21 Heterogeneity was assessed through Q and I2 statistics for each comparison, and potential sources of heterogeneity were discussed where appropriate.22 A P-value of <0.10 was considered as statistically significant, and I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were defined as low, moderate, and high estimates, respectively. To assess the extent of publication bias, a funnel plot was used. The meta-analysis was conducted using Stata 12.0. This meta-analysis had been registered on the systematic review database of PROSPERO, with the registration number CRD42016043437.

Results

Studies included in the meta-analysis

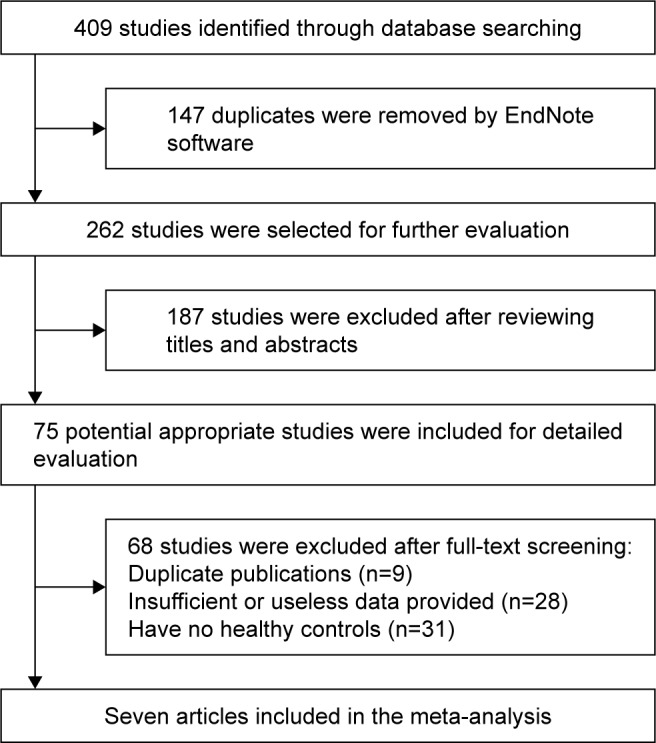

As shown in Figure 1, the search strategy identified 409 studies. Eventually, a total of seven published studies, comprising 521 patients with SS and 9,916 healthy controls, that used the same questionnaire, SF-36, were included in our study. Of the seven published studies, one was conducted in Spain, one in USA, one in Holland, one in Turkey, one in Brazil, and two in France. The characteristics of the included studies are briefly described in Table 1. Overall, there was a mean Newcastle–Ottawa scale score of 7.57 out of 9 (range, 7–9), which indicated that these studies in our meta-analysis had good quality generally.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study | Meijer et al12 | Champey et al13 | Belenguer et al23 | Rajagopalan et al24 | Koçer et al25 | Milin et al26 | Dassouki et al27 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2009 | 2006 | 2005 | 2005 | 2016 | 2016 | 2016 |

| Country | Holland | France | Spain | USA | Turkey | France | Brazil |

| Study type | Case–control study | Case–control study | Case–control study | Case–control study | Case–control study | Case–control study | Case–control study |

| Patients | Primary SS, secondary SS | Primary SS | Primary SS | Primary SS | Primary SS | Primary SS | Primary SS |

| Case (n) | 154 | 109 | 110 | 32 | 32 | 55 | 29 |

| Female (n) | 143 | 102 | 105 | 29 | 32 | 50 | 29 |

| Control | Age-, sex-matched general Dutch population | Age-matched healthy women | General healthy population | Age-, sex-matched healthy controls | Age-, sex-, and education-matched healthy women | Age-, sex-matched healthy controls | Age-, sex-, BMI-, physical activity-matched healthy women |

| Age (years), mean | 54.6 | 55.4 | 56.06 | 58.25 | 45.19 | 56.1 | 53.5 |

| Duration (years), mean | 9 | 10.6 | N/A | N/A | 2.77 | 7.4 | N/A |

| Diagnostic criteria | 2002 AECG criteria for pSS | 2002 AECG criteria for pSS | 1993 European Classification 2002 AECG criteria for pSS | ICD-9-CM or San Diego criteria | 2002 AECG criteria for pSS | 2002 AECG criteria for pSS; 2012 ACR | 2002 AECG criteria for pSS |

| Questionnaires | SF-36 | SF-36, SCL-90-R | SF-36 | SF-36, EQ-5D, DEQ, IDEEL | SF-36, HAD, BDI, EQ-5D | SF-36, HAD, MFI | SF-36, FACIT-F, MADRS |

| SF-36 scores (SS/control), mean ±SD | |||||||

| 1 PF | 62.0±25.1/74.8±25.8 | 56.0±27.6/82.1±20.3 | 65.2±27.6/84.7±24.0 | 69.46±4.10/82.28±3.60 | 73.28±19.99/81.05±19.97 | 59.90±28.50/66.90±23.80 | 75.00±18.80/85.00±8.80 |

| 2 RP | 44.0±42.7/70.3±36.3 | 30.1±39.0/81.8±31.2 | 50.0±45.7/83.2±35.2 | 41.73±6.34/81.59±5.56 | 57.81±43.27/93.42±11.31 | 35.80±42.30/50.60±39.90 | 100.0±75.00/100.0±0.00 |

| 3 RE | 71.5±41.5/79.7±34.4 | 44.7±40.7/80.5±33.1 | 73.6±42.6/88.6±30.1 | 74.94±5.78/89.70±5.05 | 59.34±32.50/85.95±25.64 | 44.70±42.30/61.60±40.90 | 100.0±66.70/100.0±50.0 |

| 4 VT | 46.0±20.4/63.8±21.0 | 38.0±19.0/58.5±18.0 | 46.9±26.5/66.9±22.1 | 44.92±3.43/66.40±3.01 | 32.19±19.63/50.53±17.15 | 34.80±17.90/40.30±17.40 | 62.50±47.50/65.00±27.5 |

| 5 MH | 70.6±18.9/73.3±19.0 | 51.1±20.0/65.5±17.3 | 53.8±23.7/73.3±20.1 | 76.37±2.58/83.59±2.26 | 36.00±18.00/40.42±13.46 | 51.60±26.30/57.40±17.70 | 64.00±36.00/80.00±30.0 |

| 6 SF | 64.5±26.6/81.3±25.6 | 50.7±25.3/79.0±22.6 | 72.7±26.1/90.1±20.0 | 67.23±3.55/91.31±3.11 | 66.02±34.23/81.58±20.57 | 51.90±26.30/59.00±19.00 | 87.50±50.00/100.0±25.0 |

| 7 BP | 68.0±23.0/68.7±25.6 | 41.8±23.9/69.1±24.0 | 55.3±29.0/79.0±27.9 | 57.62±4.09/78.08±3.59 | 53.44±20.26/73.16±20.56 | 42.60±22.60/42.50±19.70 | 11.00±11.00/22.00±27.5 |

| 8 GH | 41.9±18.4/65.7±21.5 | 33.2±19.2/67.1±18.7 | 43.4±16.7/68.3±22.3 | 47.42±3.57/77.93±3.13 | 47.53±23.14/74.76±12.82 | 40.40±16.60/43.20±18.20 | 65.00±28.80/80.00±20.0 |

| 9 PCS | 53.3±23.6/73.0±24.6 | N/A | N/A | 37.07±1.83/48.97±1.60 | N/A | 34.80±14.90/39.9±13.70 | N/A |

| 10 MCS | 64.0±21.2/74.5±21.1 | N/A | N/A | 49.70±1.53/55.07±1.33 | N/A | 33.90±13.40/36.80±12.10 | N/A |

| Total | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Design of study | Cross-sectional | Cross-sectional | Cross-sectional | Cross-sectional | Cross-sectional | Cross-sectional | Cross-sectional |

| NOS score | 8 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 7 |

Abbreviations: SS, Sjögren’s syndrome; BMI, body mass index; N/A, not available; AECG, American-European Consensus Group; pSS, primary Sjögren’s syndrome; SF-36, Short Form 36; SCL-90-R, Symptom Checklist-90-Revised; EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 Dimension; DEQ, Dry Eye Questionnaire; IDEEL, Impact of Dry Eye on Everyday Life scales; PF, physical function; RP, role physical; RE, role emotional; VT, vitality; MH, mental health; SF, social function; BP, body pain; GH, general health; PCS, physical component summary; MCS, mental component summary; NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa scale; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; ACR, American College of Rheumatology; HAD, The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; BDI, Back Depression Inventory; MFI, Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue questionnaire; MADRS, Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale.

Main results and sensitivity analysis

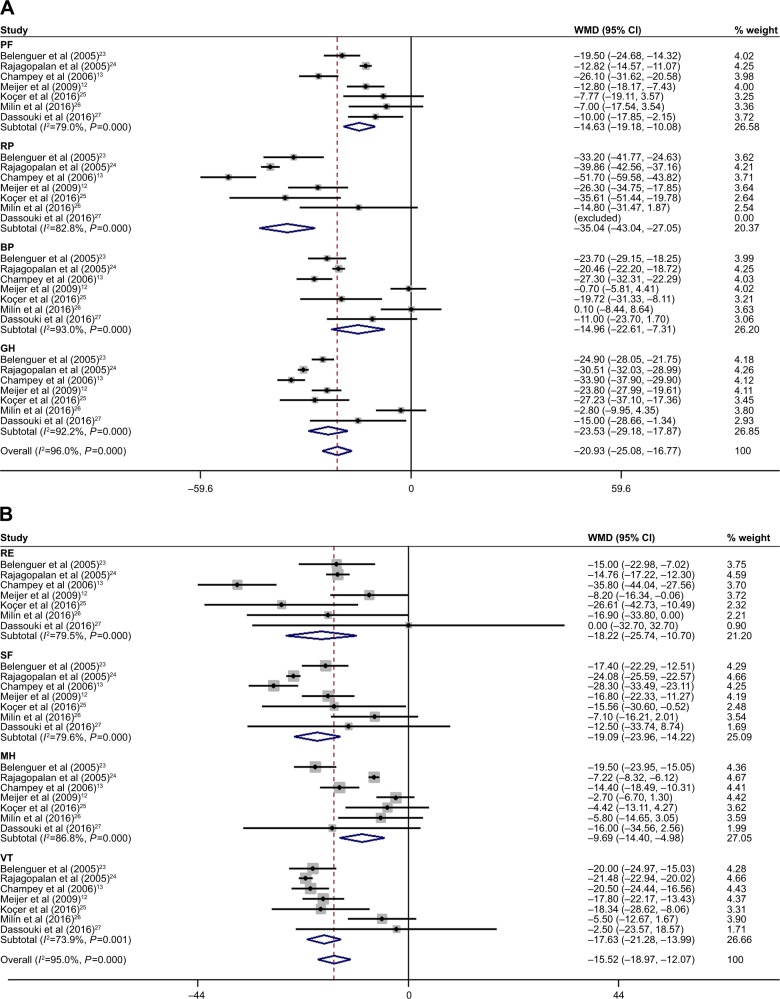

As shown in Figure 2, seven studies were included in the meta-analysis for physical function (PF), role-physical (RP) function, role-emotional (RE) function, vitality (VT), mental health (MH), social function (SF), body pain (BP), and general health (GH) of HRQoL dimensions with pSS. They were all significantly lower in every aspect, with an overall MD of −14.63 for PF (95% CI: −19.18, −10.08), −35.04 for RP (95% CI: −43.04, −27.05), −18.22 for RE (95% CI: −25.74, −10.70), −17.63 for VT (95% CI: −21.28, −13.99), −9.69 for MH (95% CI: −14.40, −4.98), −19.09 for SF (95% CI: −23.96, −14.22), −14.96 for BP (95% CI: −22.61, −7.31), and −23.53 for GH (95% CI: −29.18, −17.87). Because of the heterogeneity among aspects, they were determined using the random-effect method. Sensitivity analysis was performed in each domain of the HRQoL to assess the stability of the meta-analysis. When any single study was deleted, the corresponding pooled MD were changed slightly (data not shown), with the statistically similar results indicating a good stability of our meta-analysis.

Figure 2.

Dimensions analysis of HRQoL in pSS: (A) PCS and (B) MCS.

Note: Weights are from random-effects analysis.

Abbreviations: HRQoL, health-related quality of life; pSS, primary Sjögren’s syndrome; PCS, physical component scale; MCS, mental component scale; WMD, weighted mean difference; CI, confidence interval; PF, physical function; RP, role physical; BP, body pain; GH, general health; RE, role emotional; SF, social function; MH, mental health; VT, vitality.

Dimensions analysis of total SS

PF

Seven studies12,13,23–27 made comparisons between the PF dimension in pSS patients and controls. Patients with pSS had significantly lower values (MD, −14.63; 95% CI: −19.18, −10.08; P<0.00001), with heterogeneity among studies (P<0.0001) and I2=79% (Figure 2).

RP function

Seven studies12,13,23–27 made comparisons between RP function dimension in pSS patients and controls. Patients with pSS had significantly lower values (MD, −35.04; 95% CI: −43.04, −27.05; P<0.00001), with heterogeneity among studies (P<0.0001) and I2=83% (Figure 2).

RE function

Seven studies12,13,23–27 made comparisons between the RE function dimension in pSS patients and controls. Patients with SS had significantly lower values (MD, −18.22; 95% CI: −25.74, −10.70; P<0.0001), with heterogeneity among studies (P<0.0001) and I2=80% (Figure 2).

VT

Seven studies12,13,23–27 made comparisons between the VT dimension in pSS patients and controls. Patients with pSS had significantly lower values (MD, −17.63; 95% CI: −21.28, −13.99; P<0.00001), with heterogeneity among studies (P=0.0008) and I2=74% (Figure 2).

MH

Seven studies12,13,23–27 made comparisons between the MH function dimension in pSS patients and controls. Patients with pSS had significantly lower values (MD, −9.69; 95% CI: −14.40, −4.98; P<0.00001), with heterogeneity among studies (P<0.0001) and I2=87% (Figure 2).

SF

Seven studies12,13,23–27 made comparisons between the SF dimension in pSS patients and controls. Patients with pSS had significantly lower values (MD, −19.09; 95% CI: −23.96, −14.22; P<0.00001), with heterogeneity among studies (P<0.0001) and I2=80% (Figure 2).

BP

Seven studies12,13,23–27 made comparisons between the BP dimension in pSS patients and controls. Patients with SS had significantly lower values (MD, −14.96; 95% CI: −22.61, −7.31; P<0.00001), but there was significance among study heterogeneity (P<0.0001) and I2=93% (Figure 2).

GH

Seven studies12,13,23–27 made comparisons between the GH dimension in pSS patients and controls. Patients with pSS had significantly lower values (MD, −23.53; 95% CI: −29.18, −17.87; P<0.00001), with heterogeneity among studies (P<0.0001) and I2=92% (Figure 2).

Physical component summary (PCS)

Three studies12,24,26 made comparisons between the PCS in pSS patients and controls. Patients with pSS had significantly lower values (MD, −12.34; 95% CI: −18.42, −6.26; P<0.0001), with heterogeneity among studies (P=0.0008) and I2=86%. The combined weight of PCS was −20.93 (95% CI: −25.08, −16.77; Figure 2A).

Mental component summary (MCS)

Three studies12,24,26 made comparisons between the MCS in pSS patients and controls. Patients with pSS had significantly lower values (MD, −6.18; 95% CI: −9.58, −2.78; P=0.0004), with heterogeneity among studies (P=0.05) and I2=66%. The combined weight of MCS was −15.52 (95% CI: −18.97, −12.07; Figure 2B).

Discussion

SS is a chronic autoimmune disease that is associated with psychological disorders, physical problems, and general discomfort.6–8 Therefore, it would lead to working disability and lowered HRQoL.11,12 The present meta-analysis has demonstrated that patients with SS have lower HRQoL than people without the disorder. It showed that pSS patients scored lower in each dimension of SF-36, particularly in the RP function. Our meta-analysis included only studies with healthy controls because our objective was to compare patients with SS with non-SS healthy population.

HRQoL assessments play an important role in measuring chronic disease28 and may assist in clinical decision-making regarding choice of treatment and policy decisions. Generic instruments are designed to gage HRQoL over a broad spectrum of diseases and thus may not be sensitive enough to measure HRQoL in specific illnesses.29 Disease-specific instruments could more directly solve the specific problems of SS (eg, dryness, chronic pain, and physical and mental fatigue) in those who are significantly affected with SS, which would not be determined by a generic questionnaire (ie, SF-36). On the contrary, since there is no disease-specific HRQoL index, the most widely used tool in SS has been the SF-36.30

SS is a heterogeneous disorder, and several factors may contribute to the impairment of the HRQoL in SS, including the current disease activity, the accumulated damage, and disease-specific issues such as dryness, chronic pain, and physical and mental fatigue.31 Of course, other factors, such as depression, unemployment with disability compensation, and probably a number of different life events, not specifically linked to the disease process, may considerably impact the HRQoL as well.31 Stewart et al32 illustrated that mean SF-36 scores were significantly below group norms for all eight health dimensions and scores generally were lowest for physical measures and the ability to fulfill social and REs. In the study by Meijer et al,12 employment was lower and disability compensation rates were higher in pSS patients compared with the general population. Indeed, Dassouki et al27 had reported that pSS patients showed reduced aerobic capacity, body muscle strength, and PF; higher fatigue levels; and poorer HRQoL when compared with healthy peers matched by physical activity levels. Moreover, the physical dimension was more affected than the psychological dimension as measured with SF-36, which confirmed that pSS has a large impact on HRQoL, employment, and disability. Furthermore, Rostron et al33 found that the “role limitation – physical” was the poorest area of health, with a mean score of 31 on the SF-36 questionnaire, which had the greatest negative impact on HRQoL in pSS women. Our systematic review confirmed these conclusions and extended our evidence based on the meta-analysis.

There are some limitations in the study that should be considered. We could not perform subgroup stratification analysis of pSS and sSS to identify the distinction between them because of the limited information. Furthermore, the high statistical heterogeneity of the dimensions may represent substantial or considerable heterogeneity in the included studies, which might decrease the generalizability of the results. These dimension outcomes should be explored in future studies. Finally, the current meta-analysis was based mainly on cross-sectional data and the number of articles was relatively small. Future well-designed studies with larger sample sizes may be required to be carried out.

Conclusion

On the whole, our meta-analysis demonstrated that pSS has a significant negative impact on HRQoL, especially on the RP function domain. pSS affects patients both psychologically and physically according to the SF-36, which suggests that targeted interventions should be carried out to improve HRQoL of pSS patients. Future well-designed and well-conducted studies with larger sample sizes may be required to be carried out in different countries and ethnicities.

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81471603, 81172841, and 81401124), Social Science and Technology Innovation and Demonstration Foundation of Nantong City (MS22015003), Preventive Medicine Projects from Bureau of Jiangsu Province (Y2012083), and “Top Six Types of Talents” Financial Assistance of Jiangsu Province (10.WSN016).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Mavragani CP, Moutsopoulos HM. The geoepidemiology of Sjögren’s syndrome. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9(5):A305–A310. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mavragani CP, Moutsopoulos NM, Moutsopoulos HM. The management of Sjögren’s syndrome. Nat Clin Prac Rheumatol. 2006;2(5):252–261. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tzioufas A, Vlachoyiannopoulos P. Sjogren’s syndrome: an update on clinical, basic and diagnostic therapeutic aspects. J Autoimmun. 2012;39(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lendrem D, Mitchell S, McMeekin P, et al. Health-related utility values of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome and its predictors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(7):1362–1368. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inal V, Kitapcioglu G, Karabulut G, Keser G, Kabasakal Y. Evaluation of quality of life in relation to anxiety and depression in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Mod Rheumatol. 2010;20(6):588–597. doi: 10.1007/s10165-010-0329-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mandl T, Hammar O, Theander E, Wollmer P, Ohlsson B. Autonomic nervous dysfunction development in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a follow-up study. Rheumatology. 2010;49(6):1101–1106. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ampelas J, Wattiaux M, Van Amerongen A. Psychiatric manifestations of lupus erythematosus systemic and Sjogren’s syndrome. Encephale. 2000;27(6):588–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mengshoel AM, Norheim KB, Omdal R. Primary Sjogren’s syndrome: fatigue is an ever-present, fluctuating, and uncontrollable lack of energy. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66(8):1227–1232. doi: 10.1002/acr.22263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Leeuwen N, Bossema ER, Knoop H, et al. Psychological profiles in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome related to fatigue: a cluster analysis. Rheumatology. 2015;54(5):776–783. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keu387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Westhoff G, Dörner T, Zink A. Fatigue and depression predict physician visits and work disability in women with primary Sjögren’s syndrome: results from a cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51(2):262–269. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiang Y-J, Dai S-M. Prevalence of rheumatic diseases and disability in China. Rheumatol Int. 2009;29(5):481–490. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0809-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meijer JM, Meiners PM, Slater JJH, et al. Health-related quality of life, employment and disability in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Rheumatology. 2009;48(9):1077–1082. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Champey J, Corruble E, Gottenberg JE, et al. Quality of life and psychological status in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome and sicca symptoms without autoimmune features. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55(3):451–457. doi: 10.1002/art.21990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Testa MA, Simonson DC. Assessment of quality-of-life outcomes. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(13):835–840. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603283341306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palm Ø, Garen T, Enger TB, et al. Clinical pulmonary involvement in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: prevalence, quality of life and mortality – a retrospective study based on registry data. Rheumatology. 2013;52(1):173–179. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamel UF, Maddison P, Whitaker R. Impact of primary Sjögren’s syndrome on smell and taste: effect on quality of life. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(12):1512–1514. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho HJ, Yoo JJ, Yun CY, et al. The EULAR Sjögren’s syndrome patient reported index as an independent determinant of health-related quality of life in primary Sjögren’s syndrome patients: in comparison with non-Sjögren’s sicca patients. Rheumatology. 2013;52(12):2208–2217. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bayetto K, Logan RM. Sjogren’s syndrome: a review of aetiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Aust Dent J. 2010;55(suppl 1):39–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernández-Molina G, Sánchez-Hernández T. Clinimetric methods in Sjören’s syndrome. Paper presented at: seminars in arthritis and rheumatism; WB Saunders. 2013;42(6):627–639. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. Ottawa, ON: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 21.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belenguer R, Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, et al. Influence of clinical and immunological parameters on the health-related quality of life of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23(3):351–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rajagopalan K, Abetz L, Mertzanis P, et al. Comparing the discriminative validity of two generic and one disease-specific health-related quality of life measures in a sample of patients with dry eye. Value Health. 2005;8(2):168–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.03074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koçer B, Tezcan ME, Batur HZ, et al. Cognition, depression, fatigue, and quality of life in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: correlations. Brain Behav. 2016;6(12):1–11. doi: 10.1002/brb3.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milin M, Cornec D, Chastaing M, et al. Sicca symptoms are associated with similar fatigue, anxiety, depression, and quality-of-life impairments in patients with and without primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Joint Bone Spine. 2016;83(6):681–685. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dassouki T, Benatti FB, Pinto AJ, et al. Objectively measured physical activity and its influence on physical capacity and clinical parameters in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Lupus. 2016;0:1–8. doi: 10.1177/0961203316674819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(8):622–629. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-8-199304150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenkinson C. Assessment and Evaluation of Health and Medical Care: A Methods Text. London: McGraw-Hill Education (UK); 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seror R, Bootsma H, Bowman SJ, et al. Outcome measures for primary Sjögren’s syndrome. J Autoimmun. 2012;39(1):97–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Segal B, Bowman SJ, Fox PC, et al. Primary Sjögren’s syndrome: health experiences and predictors of health quality among patients in the United States. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:46. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stewart CM, Berg KM, Cha S, Reeves WH. Salivary dysfunction and quality of life in Sjögren syndrome: a critical oral-systemic connection. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139(3):291–299. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rostron J, Rogers S, Longman L, Kancy S, Field EA. Health-related quality of life in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome and xerostomia: a comparative study. Gerodontology. 2002;19(1):53–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2002.00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]