Abstract

The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 is an important player in stress pathways exhibiting both tumor-suppressive and oncogenic functions. Thus, expression of p21 has to be tightly controlled, which is achieved by numerous mechanisms at the transcriptional, translational, and posttranslational level. Performing immunoprecipitation of bromouridine-labeled p21 mRNAs that had been incubated before with cytoplasmic extracts of untreated HCT116 colon carcinoma cells, we identified the DEAD-box RNA helicase DDX41 as a novel regulator of p21 expression. DDX41 specifically precipitates with the 3′UTR, but not with the 5′UTR, of p21 mRNA. Knockdown of DDX41 increases basal and γ irradiation-induced p21 protein levels without affecting p21 mRNA expression. Conversely, overexpression of DDX41 strongly inhibits expression of a FLAG-p21 and a luciferase construct, but only in the presence of the p21 3′UTR. Together, these data suggest that this helicase regulates p21 expression at the translational level independent of the transcriptional activity of p53. However, knockdown of DDX41 completely fails to increase p21 protein levels in p53-deficient HCT116 cells. Moreover, posttranslational up-regulation of p21 achieved in both p53+/+ and p53−/− HCT116 cells in response to pharmaceutical inhibition of the proteasome (by MG-132) or p90 ribosomal S6 kinases (by BI-D1870) is further increased by knockdown of DDX41 only in p53-proficient but not in p53-deficient cells. Although our data demonstrate that DDX41 suppresses p21 translation without disturbing the function of p53 to directly induce p21 mRNA expression, this process indirectly requires p53, perhaps in the form of another p53 target gene or as a still undefined posttranscriptional function of p53.

Keywords: apoptosis, p53, posttranscriptional regulation, RNA helicase, translation regulation, RNA immunoprecipitation, RNA-binding protein

Introduction

Progression through the cell cycle requires accurate regulation, as loss of cell cycle control promotes tumorigenesis and is one of the hallmarks of cancer (1). Key regulators of the cell cycle are a family of serine/threonine kinases named cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs),3 which are tightly controlled by several CDK inhibitors (2). One of the most studied CDK inhibitors is p21WAF1/CIP1, which was first discovered in 1993 as CDK-interacting protein (CIP1) and wild-type p53-activated factor 1 (WAF1) (3, 4). Given the importance of CDKs for proper cell cycle progression, their inhibition was found to greatly contribute to the tumor suppressor function of p21, particularly following DNA-damaging insults. However, it soon became evident that p21 can also function in an extremely opposite manner, exhibiting potent oncogenic activities that are mainly determined by its intracellular localization (5–7). Although nuclear p21 functions predominantly as a tumor suppressor by negatively regulating DNA replication and cell proliferation, cytoplasmic p21 acts in an oncogenic manner by facilitating cell proliferation, inhibiting apoptosis, and regulating migration. Thus, together with several reports demonstrating that overexpression of p21 was observed in a variety of human cancers correlating with poor patient prognosis (8), these findings clearly document that p21 is much “more than just a break to the cell cycle” (9).

Because of its versatile and opposing functions and because improper p21 levels surely entail detrimental consequences for an organism, p21 expression has to be tightly controlled. This is achieved by diverse mechanisms that act at the transcriptional, translational, and posttranslational level (10). For example, stability, accumulation, and localization of the p21 protein critically depend on posttranslational phosphorylations mediated by diverse protein kinases (11). At the transcriptional level, p21 is mainly regulated by the tumor suppressor p53, particularly following DNA damage. However, the p21 promoter also contains response elements for several other transcription factors that are able to regulate p21 expression in response to a variety of stimuli in a p53-independent manner (12, 13). Finally, p21 expression is also controlled posttranscriptionally at the mRNA level by numerous noncoding microRNAs and RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that preferentially, but not exclusively, target sequences in the 3′UTR of the p21 mRNA (14–16). Prominent examples for p21-regulating RBPs are members of the human embryonic lethal abnormal vision (Elav)-like protein family (e.g. HuD and HuR) that increase p21 protein expression by 3′UTR-dependent stabilization of the p21 mRNA (17, 18). Others, like the two heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins K (hnRNP-K) and D (hnRNP-D; also termed AU-rich element-binding factor 1 (AUF1)) as well as Musashi 1 (Msi1), decrease p21 expression by 3′UTR-dependent destabilization and translational repression of the p21 mRNA, respectively (18–20). On the other hand, as a transcriptional coactivator of p53, hnRNP-K is also able to increase p21 expression upon DNA damage independent of the 3′UTR (21). Thus, given their central role in posttranscriptional gene expression, particularly in that of genes such as p21, which regulate cell growth and apoptosis, it is not too surprising that alterations in the expression and function of RBPs have been reported to be associated with several human diseases, including cancer (22, 23).

Also, the DEAD-box protein DDX41, a member of a large family of helicases that, like other RBPs are also involved in all aspects of RNA biology, was recently implicated in the occurrence of hematological malignancies (24). Both inherited germ line and acquired somatic DDX41 mutations were identified in patients with myeloid neoplasms, causing altered pre-mRNA splicing and RNA processing (25, 26). Furthermore, modulation of DDX41 expression greatly affected the proliferation and colony-forming capabilities of human myeloid leukemia cell lines, suggesting a tumor suppressor role for DDX41 (26). Interestingly, Abstrakt, the Drosophila homolog of DDX41, was shown to be essential for survival at all stages throughout the entire life cycle of the fly because an Abstrakt mutant fly showed specific defects in cell polarity, cell division, and apoptosis (27, 28). As DDX41 was found in a yeast two-hybrid screen to associate with caspase-2,4 which we have recently demonstrated to be required for p21 translation (29), we aimed to investigate whether DDX41 is part of a caspase-2-dependent pathway regulating p21 expression.

Results

Identification of the DEAD-box helicase DDX41 as a novel repressor of p21 expression

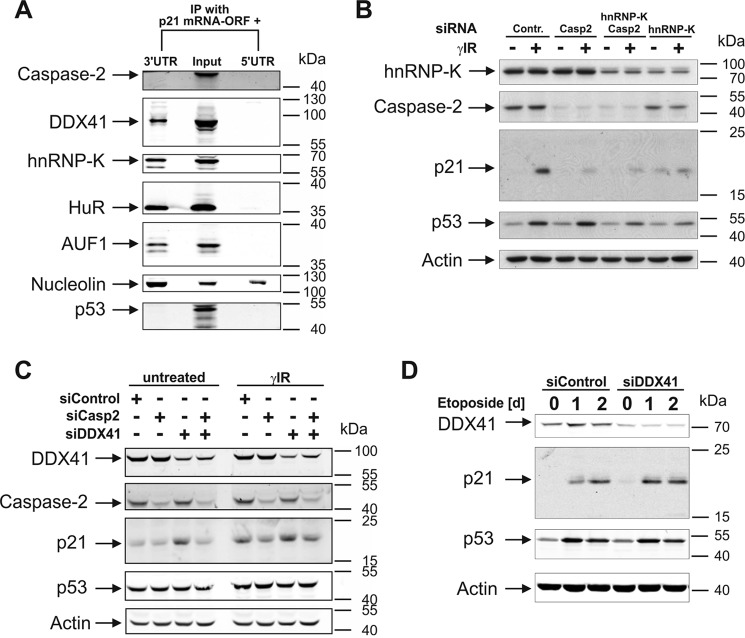

Recently, we demonstrated that caspase-2 is required for efficient p21 expression during DNA damage-induced stress responses (29). As caspase-2 neither affects transcriptional nor posttranslational events but, instead, requires the presence of the 3′UTR of the p21 mRNA, our results strongly indicate that caspase-2 positively regulates p21 expression at the translational level. To examine the underlying mechanism in more detail, we first asked whether caspase-2 regulates p21 expression by binding to the 3′UTR of the p21 mRNA. For this purpose, we incubated two bromouridine (BrU)-labeled p21 mRNA variants that, in addition to the ORF, contain either the entire 5′UTR or 3′UTR sequence with cytoplasmic extracts of untreated HCT116 colon carcinoma cells, followed by RNA immunoprecipitations using BrdU antibodies. Subsequent Western blot analyses validated this approach, as several RBPs, such as HuR, AUF1, and hnRNP-K, all known to specifically bind only to the 3′UTR of the p21 mRNA (18, 20), were accordingly detected in precipitates of the 3′UTR-containing p21 mRNA but completely absent in pulldowns of the p21 transcript that includes the 5′UTR (Fig. 1A). Nucleolin, in contrast, a highly abundant nuclear phosphoprotein that interacts with a number of mRNAs (30), was found to associate with both p21 transcripts. However, neither precipitate contained caspase-2. Also, p53, which was included because of its reported but controversially discussed RNA-binding capabilities (31), was not found. Thus, consistent with the fact that caspase-2 does not harbor an obvious RNA-binding domain, its incapability to bind to the p21 mRNA strongly indicates that caspase-2 regulates p21 translation indirectly, perhaps by association with RBPs or modulation of related pathways.

Figure 1.

DDX41 binds to the 3′UTR of the p21 mRNA, regulating its expression. A, Western blot analyses for the presence of the indicated proteins in immunoprecipitates of BrU-labeled p21 mRNAs that, in addition to the ORF, contained either the 5′UTR or the 3′UTR. Prior to immunoprecipitation (IP), the p21 mRNAs were incubated for 2 h with cytoplasmic extracts of untreated HCT116 wild-type cells. Cytoplasmic extract that was not subjected to RNA immunoprecipitation served as a control (Input). B–D, Western blot analyses for the status of the indicated proteins in HCT116 wild-type cells that were either left untransfected or transfected with the indicated siRNAs. Samples were probed 8 h after γIR (B and C) or on the indicated days following exposure to etoposide (D). Contr., control; Casp2, caspase-2. In A–D, the blots shown are representative results of two (A), three (B and D), and four (C) independent experiments. For densitometric and statistical analyses of the p21 and p53 blots shown in B–D, refer to supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

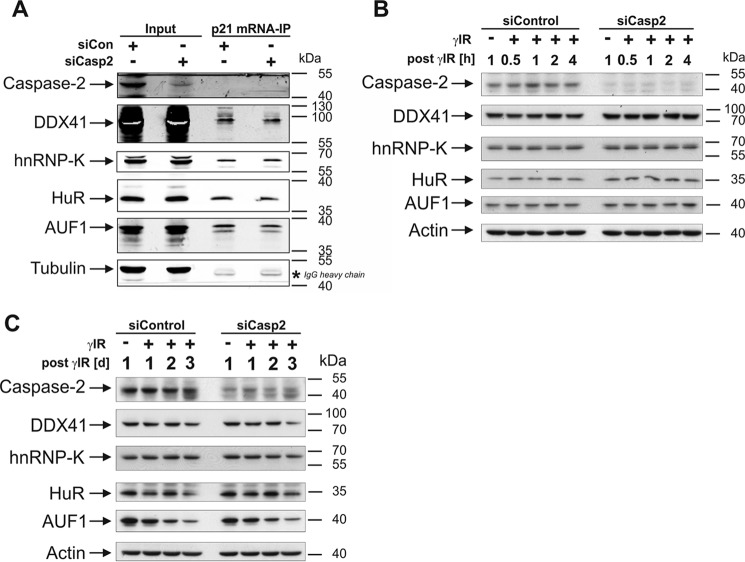

During our search to identify relevant RBPs that, together with caspase-2, regulate translation of p21, hnRNP-K and the DEAD-box helicase DDX41 were identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen as novel caspase-2-interacting RBPs.4 In contrast to hnRNP-K (20, 21), it was completely unknown whether DDX41 binds to and controls expression of the p21 mRNA. To this end, we probed the RNA precipitates with an anti-DDX41 antibody, resulting in the identification of this helicase as a novel p21 mRNA-interacting protein. DDX41 was exclusively precipitated with the 3′UTR construct but was undetectable when the 5′UTR-containing p21 transcript was used as bait (Fig. 1A). Together, these findings raised the possibility that hnRNP-K and/or DDX41 might be involved in the caspase-2-dependent translation of p21. To evaluate this hypothesis, we first analyzed basal and γ irradiation (γIR)-induced p21 protein levels in HCT116 wild-type cells following siRNA-mediated knockdown of either hnRNP-K or DDX41. We found that loss of hnRNP-K not only abrogated γIR-induced p21 expression but also greatly diminished p53 accumulation compared with the p53 levels obtained in irradiated cells transfected with the control siRNA (Fig. 1B and supplemental Fig. S1). On the contrary, knockdown of DDX41 in HCT116 cells led to elevated p21 protein levels independent of stress without up-regulating p53 expression (Fig. 1, C and D, and supplemental Figs. S2 and S3). Thus, it appears that DDX41 negatively regulates p21 expression independent of stress and p53 at the posttranscriptional level, whereas hnRNP-K most likely modulates this event in a transcriptional manner by controlling p53 levels as described previously (21). Therefore, these results suggest that only DDX41, but not hnRNP-K, may be involved in the translational regulation of p21 by caspase-2. However, neither DDX41 nor hnRNP-K knockdown rescued γIR-induced p21 expression in the absence of caspase-2, arguing against this possibility (Fig. 1, B and C, and supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). Consistently, the absence of caspase-2 neither affected binding of DDX41 or hnRNP-K (or any other RBP tested) to the p21 mRNA (Fig. 2A) nor their expression in untreated or irradiated HCT116 cells (Fig. 2, B and C). Thus, although we have clearly identified DDX41 as a novel inhibitor of p21 expression, it is highly unlikely that this DEAD-box helicase mediates this event in a caspase-2-controlled manner.

Figure 2.

DDX41 controls the expression of p21 independent of caspase-2. A, Western blot analyses for the presence of the indicated proteins in immunoprecipitates of the BrU-labeled 3′UTR-containing p21 mRNA. Before immunoprecipitation (IP), the p21 mRNA was incubated for 2 h with cytoplasmic extracts of HCT116 wild-type cells that were transfected with control or caspase-2 siRNA. Cytoplasmic extracts that were not subjected to RNA immunoprecipitation served as controls (Input). B and C, Western blot analyses for the status of the indicated proteins in extracts of HCT116 wild-type cells transfected with either control or caspase-2 siRNA. Samples were probed at the indicated times after γIR. The blots shown are representative results of five (A) and three (B and C) independent experiments.

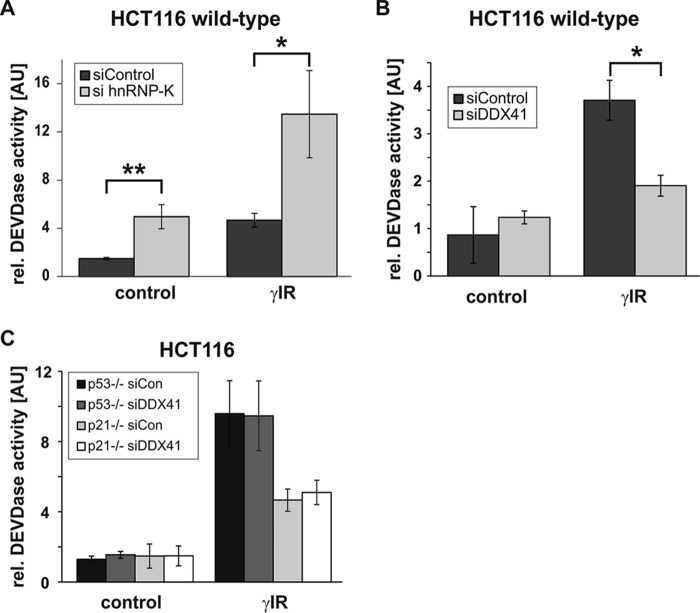

Knockdown of DDX41 inhibits caspase-3-like DEVDase activity in a p21-dependent manner

We thus aimed to further identify the mechanism by which DDX41 inhibits expression of p21. In this context, it is necessary to mention that wild-type HCT116 cells (p53+/+) do not (or only barely) undergo apoptosis following exposure to γIR (32). Although this treatment induces some caspase-3-like DEVDase activity in a small fraction of these cells, the majority is driven into a premature senescence program because of the p53-dependent induction of p21. In contrast, the two isogenic HCT116 cell lines (p53−/−; p21−/−) that are unable to up-regulate p21 protein expression succumb to apoptosis upon γIR exposure. Interestingly, knockdown of hnRNP-K sensitized HCT116 wild-type cells to γIR-induced apoptosis, as evidenced by morphological criteria (supplemental Fig. S4) and greatly enhanced caspase-3-like DEVDase activities (Fig. 3A). As this knockdown also resulted in inhibition of p21 expression (Fig. 1B and supplemental Fig. S1A), these data suggest that hnRNP-K deficiency causes apoptosis by down-regulating the antiapoptotic p21 protein. However, the hnRNP-K siRNA alone also induced these events in non-irradiated cells (Fig. 3A and supplemental Fig. S4) without affecting the low background levels of p53 and p21 (Fig. 1B and supplemental Fig. S1). Thus, it is clear that loss of hnRNP-K kills the cells independent of these stress sensors. In contrast, knockdown of DDX41 further protected HCT116 wild-type cells from γIR-induced apoptosis in a p21-dependent manner. This is because the up-regulation of p21 observed in these cells in response to the DDX41 siRNA (Fig. 1C and supplemental Fig. S2) strongly inhibited the low background DEVDase activities that are induced in these cells by γIR (Fig. 3B). On the other hand, knockdown of DDX41 did not affect γIR-induced DEVDase activities in p53- and p21-deficient HCT116 cells (Fig. 3C), which, because of the lack of p21, succumb to apoptosis upon γIR exposure. Therefore, our findings clearly demonstrate that inhibition of the low DEVDase activity, which can even be detected in irradiated wild-type HCT116 cells, is indeed due to increased p21 expression in response to DDX41 knockdown and is not caused by an unspecific off-target effect of the DDX41 siRNA.

Figure 3.

Knockdown of DDX41 inhibits DEVDase activity in a p21-dependent manner. A–C, fluorometric determination of caspase-3-like DEVDase activities in HCT116 cells that were transfected with the indicated siRNAs before they were exposed to γIR. Cells were analyzed 2 days after γIR. The arbitrary units (AU) shown are the mean of three (B) and four (A and C) independent experiments ± S.D. Note the different y axis scales. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

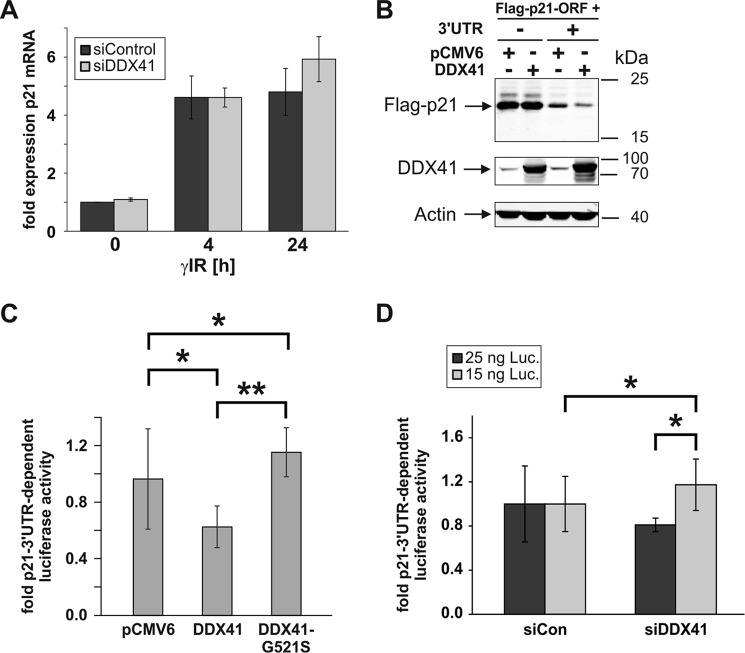

DDX41 negatively regulates p21 expression at the translational level

So far, we have shown that the DEAD-box helicase DDX41 specifically binds to the 3′UTR of the p21 mRNA, inhibiting its expression without affecting p53 levels. Together, these findings imply that DDX41 mediates this process, most likely in a p53-independent manner, at the posttranscriptional level. To verify this assumption, we compared basal and γIR-induced p21 mRNA levels in the presence and absence of DDX41. Indeed, we found that both basal and irradiation-induced p21 mRNA levels remained almost unaltered following knockdown of DDX41 (Fig. 4A), suggesting that this DEAD-box helicase inhibits p21 expression at the translational level. To further confirm this possibility, HCT116 wild-type cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged p21 cDNA constructs that, in addition to the coding region, either contained or lacked the entire 1.5-kb 3′UTR of the p21 mRNA. Of note, because of the presence of various regulatory elements within the 3′UTR, the FLAG-p21 construct containing this untranslated region is less well expressed than the construct consisting of only the ORF (29). Consistent with our previous result (Fig. 1C and supplemental Fig. S2), overexpression of DDX41 significantly inhibited expression of the FLAG-p21 construct, but only in the presence of the 3′UTR (Fig. 4B and supplemental Fig. S5). We also performed reporter gene assays comparing the effect of DDX41 on CMV-driven luciferase activities of vectors that either contained or lacked the p21 3′UTR downstream of the luciferase gene. In agreement with the experiment described above, exogenously transfected DDX41 significantly compromised luciferase expression in the presence of the p21 3′UTR (Fig. 4C and supplemental Fig. S6). Conversely, luciferase activities increased in a p21 3′UTR-dependent manner following knockdown of DDX41 (Fig. 4D). Although significant, the -fold 3′UTR-dependent induction of luciferase activity was rather weak. A possible explanation for this may be an overload of luciferase expression that could only be enhanced by the DDX41 knockdown when much lower amounts of the luciferase expression plasmids were used (15 ng) than in the DDX41 overexpression study (100 ng, Fig. 4C). These data provide strong evidence that DDX41 requires the 3′UTR of the p21 mRNA to inhibit its expression at the translational level.

Figure 4.

DDX41 requires its helicase activity to regulate p21 expression at the translational level. A, quantitative real-time PCR for the determination of p21 mRNA expression levels in HCT116 wild-type cells that were either transfected with the control or the DDX41 siRNA before they were exposed to γIR. Total RNA was isolated 0, 4, and 24 h after γIR and analyzed with transcript-specific probes from Life Technologies. The data shown are the mean of three independent experiments ± S.D. B, Western blot analyses showing the influence of overexpression of DDX41 in HCT116 wild-type cells on the expression of FLAG-p21 constructs consisting of the p21 ORF with or without the 3′UTR. The blots shown are representative results of three independent experiments. For densitometric and statistical analyses of FLAG-p21 expression, refer to supplemental Fig. S5. C and D, determination of luciferase activities in HCT116 wild-type cells transfected with luciferase (Luc) expression constructs containing or lacking the p21–3′UTR together with an empty vector or vectors encoding wild-type DDX41 or the DDX41-G521S mutant (C) or together with the control or the DDX41 siRNA (D). Note that 100 ng of luciferase expression plasmids was used for DDX41 overexpression analysis (C) but only 15 and 25 ng for the DDX41 siRNA experiment (D). Depicted are the mean p21–3′UTR-dependent -fold changes in luciferase activities ± S.D. The data shown in C were derived from four (DDX41-G521S mutant) and seven independent experiments (empty vector and wild-type DDX41), whereas values from five independent experiments are shown in D. For expression control of wild-type DDX41 and the DDX41-G521S mutant, refer to supplemental Fig. S6. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

Undoubtedly, helicase activity is crucial for several functions of DEAD-box proteins (33). To assess whether the helicase activity of DDX41 is also fundamental for its p21-suppressive function, we generated a DDX41 mutant (G521S) containing a point mutation in the highly conserved motif VI (HRIGR), which is absolutely essential for ATP hydrolysis and, thus, helicase activity of DEAD-box proteins (34). We have also chosen this particular mutation because the corresponding Drosophila Abstrakt mutant (G517S) showed complete loss of function compared with the wild-type protein (35). Comparing luciferase activities in response to either the mutant or the wild-type DDX41 protein, we found that the G521S mutant completely lost the ability to suppress luciferase expression in a p21 3′UTR-dependent manner (Fig. 4C and supplemental Fig. S6), implying a crucial role for the HRIGR motif in this process.

DDX41-regulated p21 translation requires a p53-dependent posttranscriptional event

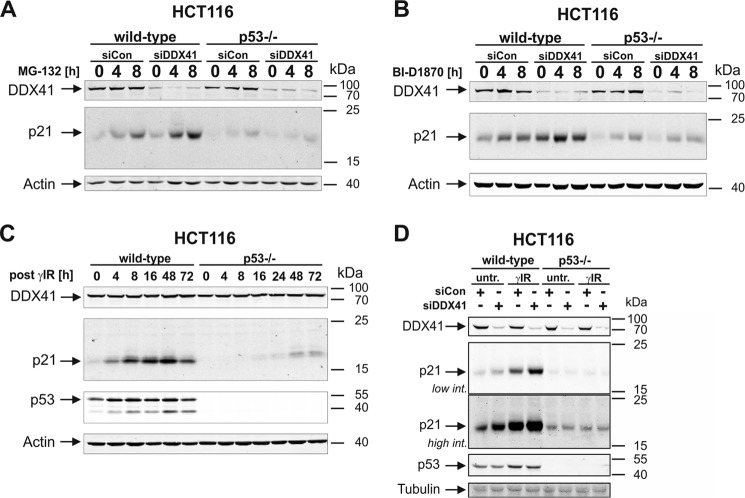

To corroborate these findings and to further exclude a posttranslational effect, we assessed the influence of DDX41 knockdown on the posttranslational control of p21 expression. For this purpose, we exposed HCT116 cells to the proteasomal inhibitor MG-132 or to BI-D1870, a small-molecule inhibitor of p90 ribosomal S6 kinases (RSKs) (36), which we have recently shown to induce rapid accumulation of the short-lived p21 protein in a p53- and transcription-independent manner (37). Here we found that accumulation of the p21 protein that was induced in HCT116 wild-type cells in response to both compounds could be even further increased following depletion of DDX41 (Fig. 5, A and B, and supplemental Fig. S7). These results provide additional evidence that this DEAD-box helicase inhibits p21 expression at the translational level and not by promoting proteasomal degradation of the protein. Remarkably, although so far our data clearly demonstrate that DDX41 controls p21 expression independent of the transcriptional activity of p53 (Figs. 1, C and D, and 4), loss of DDX41 completely failed to increase MG-132- or BI-D1870-induced p21 accumulation in p53-deficient HCT116 cells (Fig. 5, A and B, and supplemental Fig. S7), implying a role of p53 in this process. To explore this discrepancy, we analyzed the effect of p53 on the expression and function of DDX41. Consistent with our finding that DDX41 protein levels remained unaltered following exposure of HCT116 wild-type cells to γIR (Fig. 2, B and C), they were also uncompromised by the lack of p53 (Fig. 5C). However, in contrast to its effect on p21 expression in HCT116 wild-type cells (Figs. 1, C and D, and 4), knockdown of DDX41 in p53-deficient HCT116 cells completely failed to increase basal or irradiation-induced endogenous p21 protein levels (Fig. 5D). Together, these data not only verify DDX41 as a novel translational repressor of p21 expression but also suggest that this process requires a function of p53 that is unrelated to its role as a direct transcriptional p21 inducer.

Figure 5.

DDX41-regulated p21 expression requires a p53-dependent posttranscriptional event. A and B, Western blot analyses for the status of the indicated proteins in extracts of wild-type and p53-deficient HCT116 cells that were exposed for the indicated times to MG-132 (A) or BI-D1870 (B) after they were transfected with the control or the DDX41 siRNA. For densitometric and statistical analyses of p21 expression, refer to supplemental Fig. S7. C, Western blot analyses for the status of the indicated proteins in extracts of wild-type and p53-deficient HCT116 cells that were analyzed at the indicated times after γIR. D, Western blot analyses for the status of the indicated proteins in extracts of untreated (untr) and irradiated wild-type and p53-deficient HCT116 cells that were transfected before with either control or DDX41 siRNA. Samples were probed 8 h after γIR. All blots shown are representative results of at least three independent experiments. Low/high int., lower/higher scanning intensity.

Discussion

DEAD-box proteins represent the largest family of RNA helicases, which regulate all aspects of RNA biology, from synthesis in the nucleus to availability and degradation in the cytoplasm. Thus, these enzymes have numerous opportunities to shape and fine-tune gene expression at multiple levels (33, 38). Mechanistically, DEAD-box RNA helicases do not act solely by unwinding RNA duplexes. They also promote duplex formation, displace proteins from RNA, and function as assembly platforms for larger ribonucleoprotein complexes. Such a remarkable range of biological activities enables them to be involved in diverse processes such as virus replication, innate immune responses toward viral and bacterial metabolites, and developmental processes (24, 38). Furthermore, as several DEAD-box proteins, including DDX41, have been linked to cellular proliferation and neoplastic transformation, they are also considered important players in cancer development and progression (26, 39).

Besides functioning as an intracellular DNA sensor (40) and a putative tumor suppressor (26), little information is available about specific targets of the DEAD-box protein DDX41. Thus, to our knowledge, this is the first report identifying DDX41 as a novel repressor of p21 expression. Other DEAD-box proteins were also recently demonstrated to control expression of this CDK inhibitor. However, in contrast to DDX41, which binds to the 3′UTR of the p21 mRNA and thus directly inhibits p21 translation both under basal and stress conditions, DDX3 (also known as DDX3X) and DDX5 (also known as p68) were shown to transcriptionally up-regulate p21 indirectly in a p53-dependent manner (41, 42).

As we demonstrate here that expression of p21, which functions in several cancer cell lines, including HCT116 cells, in an antiapoptotic manner (32), is negatively controlled by DDX41, our data support an oncogenic role of this DEAD-box protein. Although being contradictory to the abovementioned study claiming a tumor suppressor function for DDX41 in human myeloid leukemia cells (26), our view is consistent with data from a genome-scale RNA-mediated interference screen in HeLa cells demonstrating reduced cell numbers following knockdown of DDX41 (43). Although neither study examined p21 protein levels upon DDX41 modulation, such opposing functions are apparently not uncommon among DEAD-box proteins. For instance, with the transcriptional induction of p21, DDX5 exhibits tumor suppressor activity (44), but the additional up-regulation of pro-proliferative genes such as cyclin D1 and c-Myc, as well as genes required for DNA replication, implies potent oncogenic functions (45). Furthermore, depending on the cancer type, DEAD-box proteins differentially affect expression and function of an individual target. Although DDX3 was shown to transcriptionally activate the p21 promoter in lung cancer cells and in hepatocellular carcinoma, supporting its tumor suppressor role (42), no correlation was found between DDX3 and p21 expression in aggressive breast cancer cells (46). Likewise, DDX5 and DDX17, two highly related DEAD-box helicases with partially redundant functions, are able to enhance the transcriptional activity of NFAT5, which regulates a variety of signaling pathways involved in cell growth and development (47). On the other hand, they also modulate alternative splicing of NFAT5, reducing its expression level (47). Thus, depending on the cancer type, treatment modalities, and various co-factors, several DEAD-box proteins possess both oncogenic and tumor suppressor functions.

We have shown that the increase in p21 protein expression upon loss of DDX41 proceeds without affecting basal and γIR-induced p21 mRNA levels. Moreover, knockdown and overexpression of DDX41 were found to modulate the expression of a FLAG-p21 or a luciferase reporter gene construct only in the presence of the p21 3′UTR but not in its absence. Together, our data strongly indicate that DDX41 controls p21 at the translational level. Although some RNA helicases might not have exactly the same molecular functions in different species, overexpression of Abstrakt, the Drosophila homolog of DDX41, was found to reduce cellular expression of the sorting protein nexin 2 (SNX2) without altering its steady-state mRNA levels (48). Unfortunately, the authors did not analyze possible posttranslational mechanisms. This would have been very interesting, particularly in view of the fact that Abstrakt and SNX2 were found to interact with each other. Also expression of Inscuteable (Insc), a protein involved in the coordination of cell polarity and spindle orientation in Drosophila, was reported to be controlled by Abstrakt at the posttranscriptional level (28). By physically interacting with the Insc mRNA, Abstrakt was shown to be required for maintaining Insc protein levels while leaving Insc mRNA levels unchanged. Interestingly, with the up- and down-regulation of Insc and SNX2, respectively, Abstrakt regulates protein expression in an opposing manner. This feature also appears to be quite common among DEAD-box RNA helicases, as DDX3 and DDX6 are also known to either repress or enhance translation in a substrate-dependent manner (38). In addition, certain DEAD-box proteins can also affect splicing both in a positive and negative manner (49). Despite these and our findings clearly documenting translational regulation of gene expression by DDX41/Abstrakt, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that DDX41 regulates p21 expression by alternative means, perhaps by controlling transport or storage of the p21 mRNA, thereby modulating its accessibility to active ribosome complexes (38).

Curiously, although p53 protein and p21 mRNA levels remained unaltered during DDX41 knockdown, strongly implying that the resulting increase in p21 protein expression is not caused by direct p53-dependent transcriptional activation of the p21 promoter, modulation of p21 expression by DDX41 could be only achieved in the presence of p53. Even the posttranslational up-regulation of p21, which can be observed in both p53+/+ and p53−/− HCT116 cell lines in response to pharmaceutical inhibitors of the proteasome (MG-132) or p90 ribosomal S6 kinases (BI-D1870), was further increased by knockdown of DDX41 in p53-proficient but not in p53-deficient cells. Thus, it appears that DDX41 requires p53 somewhere at the posttranscriptional level to inhibit expression of p21. Although such a scenario appears odd at first glance, particularly in view of the fact that p53 functions mainly as a transcription factor, several well known p53 target genes are regulated by this tumor suppressor at the translational level (50). This can be achieved by p53 in distinct ways, for instance by directly interacting with target mRNAs (31). In agreement with such a function, cytoplasmic p53 protein was found to be associated with the polysomal fraction (51). However, our finding that p53 was undetectable in p21 mRNA precipitates strongly argues against this possibility.

In addition, by transactivating numerous microRNAs and RBPs that target mRNAs either individually or in combination with each other, p53 proves to be extremely versatile in fine-tuning gene expression at the posttranscriptional level (52, 53). Possible candidates for a role in DDX41-mediated p21 suppression are, for instance, miR-22, poly(C)-binding protein 4 (PCBP4), ribosomal protein S27-like (RPS27L), and the two RNA-binding motif proteins 24 and 38, as all of them are known p53 targets regulating p21 expression (54–58). However, with the exception of RPS27L, which controls p21 expression via a still undefined mechanism, the remaining molecules mainly modulate the stability of the p21 mRNA, a process that, according to our data, is probably not involved in the translational suppression of p21 by DDX41. In addition, to our knowledge, there are no data available linking miR-22 or any of these RBPs to DDX41 on either a functional or physically interactive level. On the other hand, although certain p21-regulating RBPs such as PCBP2, hnRNP-K, and AUF1 were recently shown to interact with DDX41 (26), they do not represent p53 target genes. Therefore, further efforts are required to identify the p53-dependent factors involved in the observed DDX41-mediated suppression of p21 translation.

Together, these observations are not only consistent with a posttranscriptional role for p53 in the DDX41-mediated suppression of p21 translation, they may even help to explain the aforementioned contradictory roles (oncogenic versus tumor-suppressive) of DDX41 observed in our study and a previous one (26). In contrast to our cellular system, in which we used HCT116 cells expressing the p53 wild-type protein, Polprasert and colleagues studied the effects of DDX41 solely in the p53-null cell lines K562 and U937 (26). In addition, the DDX41 lesions they identified in patients with myeloid neoplasms coincided with several other mutations, among which p53 was found to be the most frequently mutated gene. Thus, it would now be very interesting to examine whether DDX41 would still function in a similar tumor-suppressive manner if these experiments were conducted in p53 wild-type cells.

In summary, we have identified DDX41 as a novel p21 mRNA-binding protein that negatively controls the expression of this CDK inhibitor at the translational level. However, the posttranscriptional role of p53 in this process remains elusive, as it is completely unknown whether DDX41 requires a p53-controlled miRNA or RBP (or both) or whether this DEAD-box helicase relies on another, still undefined function of p53.

Experimental procedures

Cell lines, reagents, and antibodies

HCT116 wild-type colon carcinoma cells and their checkpoint-deficient isogenic counterparts (p53−/− and p21−/−) were maintained in McCoy's 5A medium (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Biowest SAS, Nuaille, France), 10 mm glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin (Biochrom GmbH, Berlin, Germany). The cell lines were authenticated by DNA fingerprinting (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany) and are routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination. The fluorogenic caspase-3 substrate N-acetyl-DEVD-aminomethylcoumarin was from Biomol (Hamburg, Germany). MG-132 and BI-D1870 were purchased from Biozol (Eching, Germany) and from Hilary McLauchlan (Dundee, Scotland), respectively. From BD Biosciences we purchased the monoclonal p21 antibody (clone SX118, 556430), whereas the monoclonal p53 antibody (Ab6, OP43) was from Calbiochem (Bad Soden, Germany). The polyclonal rabbit nucleolin antibody (22758) was from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). The polyclonal rabbit hnRNP-K (R332, 4675) and HuR (07-468) antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA) and from Merck Millipore (Darmstadt, Germany), respectively. The rat caspase-2 mAb (clone 11B4, ALX-804-356) was from Enzo Life Sciences GmbH (Lörrach, Germany). From Sigma-Aldrich (Deisenhofen, Germany), we obtained the monoclonal β-actin (AC-74, A5316) and tubulin (T6199) antibodies, the polyclonal DDX41 (HPA017911), FLAG (F7425), and hnRNP-D (AUF1, HPA004911) antibodies, the topoisomerase II inhibitor etoposide, as well as the protease inhibitors PMSF, aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin. Infrared fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies were from Li-Cor Biosciences (Lincoln, NE).

Treatment of cells

Cells were exposed routinely to 20 Gy γIR (at 175 kV and 15 mA) using a Gulmay RS225 X-ray system from X-Strahl (Camberley, UK) or treated with etoposide (50 μm), MG-132 (10 μm), or BI-D1870 (10 μm) for the indicated times.

Preparation of cell extracts, Western blotting, and fluorometric determination of caspase-3-like DEVDase activity

For Western blotting and fluorometric determination of caspase-3-like DEVDase activities, total cell extracts were prepared in lysis buffer containing 1% Nonidet P-40, 50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 1 μm DTT, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Protein concentrations were determined with the Bio-Rad protein assay. 30 μg of protein per sample was separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and electroblotted to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Schwalbach, Germany). Following primary antibody incubation, proteins were visualized by infrared fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies using the Li-Cor Odyssey imaging system. Caspase-3-like DEVDase activities were assessed using 50 μg of extract per sample as described previously (32) and are presented as arbitrary units.

p21 mRNA immunoprecipitation

To analyze binding of RBPs to the p21 mRNA, BrU-labeled p21 mRNAs that, in addition to the ORF, contained the 5′UTR or 3′UTR were generated with the mMESSAGE mMACHINE® T7 transcription kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using corresponding pcDNA4 templates (29) according to the protocol of the manufacturer. The employed ratio of bromouridine triphosphate to standard UTP was 1:3. The quality of the generated mRNAs was verified by optical density measurements and RNA-agarose gel electrophoresis. Immunoprecipitations of the BrU-labeled p21 mRNAs were carried out at 4 °C with the RiboTrap kit according to the protocol of the manufacturer (MBL, Woburn, MA) as follows. Untreated HCT116 wild-type cells were harvested from four 15-cm dishes (in total, ∼1 × 108 cells), and cytoplasmic extracts were generated in 1200 μl of cytoplasmic extraction buffer (supplemented with the protease inhibitors leupeptin, aprotinin, and PMSF; 200 units/ml RNase inhibitor RNAseOUT; and 1.5 μm DTT). Extracts were precleared with protein G-Sepharose beads for 1 h. In the meantime, the BrU-labeled p21 mRNAs were coupled to anti-BrdU antibody-conjugated protein G-Sepharose beads. Subsequently, these p21 mRNA antibody-coupled beads (50 pmol p21 mRNA/sample) were incubated for 2 h with the precleared cytoplasmic extracts. Nonspecific binding proteins were removed by washing the samples four times with the provided washing buffers 1 or 2 supplemented with 1.5 μm DTT. Elution of the p21 mRNAs and its associated RBPs was achieved by using 50 μl of elution buffer (BrdU in PBS). The presence of RBPs in the precipitates was analyzed by Western blotting. Each immunoprecipitate was used for two to four Western blot analyses.

Transfection of siRNAs and plasmids

ON-TARGET Plus SMARTpool siRNAs were purchased from Dharmacon RNA Technologies (Lafayette, CO). Knockdown was performed in 6-well plates according to the instructions of the manufacturer using 4 μl/well Dharmafect 1 as the transfection reagent together with 200 nmol siRNAs/well. Twenty-four to seventy-two hours after transfection, cells were divided equally to receive either no treatment or exposure to γIR, etoposide, MG-132, or BI-D1870. At the indicated time points following treatment, cells were harvested and directly analyzed by Western blotting and by fluorometric caspase substrate assay for successful knockdown of the target protein and DEVDase activity, respectively. The pCMV6-DDX41 plasmid was from OriGene Technologies (Rockville, MD), and the generation of the FLAG-p21 constructs (with or without the 3′UTR) was described previously (29). For the simultaneous transfection of plasmids in 6-well plates, Dharmafect DUO transfection reagent (4 μl/well) was used according to the protocol of the manufacturer. Briefly, HCT116 cells seeded in 6-well plates were transfected with 1 μg of FLAG-p21 expression plasmids together with either 1 μg of empty pCMV6 vector or the DDX41-expressing construct. Twenty-four hours after plasmid transfection, the cells were harvested and analyzed by Western blotting.

Real-time PCR

To determine the influence of DDX41 on the expression of p21 mRNA, cells were transfected with DDX41 or control siRNA in 6-well plates. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were either left untreated or exposed to γIR. Total RNA was isolated with the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and reverse-transcribed with a high-capacity cDNA kit (Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific). TaqMan gene expression probes for human p21 and GAPDH mRNAs (Life Technologies) were employed to analyze their relative expression levels using the 7300 real-time PCR system (Life Technologies). GAPDH mRNA served as an endogenous normalization control for every sample. The -fold induction of the p21 mRNA was calculated via the 2Δ(ΔCt) method, normalizing all samples to the level of the analyzed mRNA in control siRNA-transfected HCT116 wild-type cells.

DDX41 helicase mutagenesis

The helicase-inactive DDX41-G521S mutant was generated using the Q5 site-directed mutagenesis kit (New England Biolabs, Frankfurt am Main, Germany) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Briefly, 10 ng of pCMV6-DDX41 was used as the template, together with the forward primer DDX41-G521S-fw (5′-GTA CAC CGG ATT AGC CGC ACC GG-3′) and the reverse primer DDX41-G521S-rev (5′-ATA GTT CTC AAT CTC CTC TGG CA-3′) to generate the pCMV6-DDX41-G521S construct. The bold and underlined A indicates the point mutation. Successful mutagenesis was verified by sequencing.

Luciferase assay

To determine the direct effect of DDX41 on the expression of luciferase constructs containing or lacking the p21 3′UTR, reporter gene assays were employed. Therefore, HCT116 wild-type cells were transfected in 12-well plates with 100 ng of pcDNA-LUC or pcDNA-LUC-p21–3′UTR plasmids (15). In addition to these plasmids encoding firefly luciferase, 750 ng of either an empty vector (pCMV6), a wild-type DDX41-expressing construct (pCMV6-DDX41), or the helicase-inactive DDX41 mutant (pCMV6-DDX41-G521S) was added to the transfection mixture. For normalization purposes, 5 ng of a plasmid encoding Renilla luciferase (pGL4.74, Promega, Madison, WI) was added to each transfection mixture. For the combination experiments with siRNAs and luciferase expression constructs, HCT116 cells seeded in 6-well plates were first transfected with siRNAs using Dharmafect I (4 μl/well) transfection reagent. Twenty-four hours after siRNA transfection, the cells were trypsinized, divided equally into several wells of a 12-well plate, and transfected after an additional 24 h with varying (25 and 15 ng/well) amounts of the two abovementioned firefly luciferase expression constructs in addition to 5 ng of the Renilla luciferase plasmid used for normalization. The Dual-Luciferase reporter system (Promega) was used in both experimental setups according to the protocol of the manufacturer. Cells were lysed 24 h after transfection in 250 μl of passive lysis buffer (PLB), and luciferase activities were determined successively in a Centro LB 960 microplate luminometer (Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany). The obtained firefly luciferase activities were normalized to the Renilla luciferase activities to eliminate experimental variance because of varying transfection efficiencies.

Densitometric and statistical analyses

Densitometric analyses were performed using Odyssey V3.0 or ImageJ analysis software. For statistical analyses, paired Student's t test was performed (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.005).

Author contributions

R. U. J. and D. S. conceptualized and planned the project and interpreted the data. R. U. J., D. S., and W. B. drafted and wrote the paper. D. P. designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments shown in Figs. 1; 2A; 3, B and C; and 4A with assistance from D. S. A. R. performed and analyzed the experiments shown in Fig. 2, B and C, as well as the mutagenesis studies. C. R. performed and analyzed the experiments shown in Fig. 5C. D. S. performed and analyzed the experiments shown in Figs. 3A; 4, B–D (together with A. R. and C. R.); and 5, A, B, and D, with technical assistance from C. D. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final form of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Disselhoff for excellent technical assistance and Bert Vogelstein for providing the HCT116 wild-type cell line together with the checkpoint-deficient isogenic counterparts (p53−/− and p21−/−). We also thank X. He for providing the luciferase cDNA constructs containing or lacking the p21 3′UTR.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants JA 1060/3-1 and JA 1060/5-1 (to R. U. J.) and SO 881/5-1 (to D. S.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S7.

C. Brancolini (University of Udine, Italy), personal communication.

- CDK

- cyclin-dependent kinase

- RBP

- RNA-binding protein

- hnRNP

- heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein

- BrU

- bromouridine

- γIR

- γ irradiation

- RSK

- ribosomal S6 kinase.

References

- 1. Hanahan D., and Weinberg R. A. (2011) Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Malumbres M., and Barbacid M. (2009) Cell cycle, CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 153–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. el-Deiry W. S., Tokino T., Velculescu V. E., Levy D. B., Parsons R., Trent J. M., Lin D., Mercer W. E., Kinzler K. W., and Vogelstein B. (1993) WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 75, 817–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xiong Y., Hannon G. J., Zhang H., Casso D., Kobayashi R., and Beach D. (1993) p21 is a universal inhibitor of cyclin kinases. Nature 366, 701–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jänicke R. U., Sohn D., Essmann F., and Schulze-Osthoff K. (2007) The multiple battles fought by anti-apoptotic p21. Cell Cycle 6, 407–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Warfel N. A., and El-Deiry W. S. (2013) p21WAF1 and tumourigenesis: 20 years after. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 25, 52–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weiss R. H. (2003) p21Waf1/Cip1 as a therapeutic target in breast and other cancers. Cancer Cell 4, 425–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abbas T., and Dutta A. (2009) p21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 400–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dotto G. P. (2000) p21(WAF1/Cip1): more than a break to the cell cycle? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1471, M43–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jung Y. S., Qian Y., and Chen X. (2010) Examination of the expanding pathways for the regulation of p21 expression and activity. Cell Signal. 22, 1003–1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Child E. S., and Mann D. J. (2006) The intricacies of p21 phosphorylation: protein/protein interactions, subcellular localization and stability. Cell Cycle 5, 1313–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gartel A. L., and Tyner A. L. (1999) Transcriptional regulation of the p21((WAF1/CIP1)) gene. Exp. Cell Res. 246, 280–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sohn D., Peters D., Piekorz R. P., Budach W., and Jänicke R. U. (2016) miR-30e controls DNA damage-induced stress responses by modulating expression of the CDK inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1 and caspase-3. Oncotarget 7, 15915–15929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Borgdorff V., Lleonart M. E., Bishop C. L., Fessart D., Bergin A. H., Overhoff M. G., and Beach D. H. (2010) Multiple microRNAs rescue from Ras-induced senescence by inhibiting p21(Waf1/Cip1). Oncogene 29, 2262–2271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu S., Huang S., Ding J., Zhao Y., Liang L., Liu T., Zhan R., and He X. (2010) Multiple microRNAs modulate p21Cip1/Waf1 expression by directly targeting its 3′ untranslated region. Oncogene 29, 2302–2308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang J., and Chen X. (2008) Posttranscriptional regulation of p53 and its targets by RNA-binding proteins. Curr. Mol. Med. 8, 845–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang W., Furneaux H., Cheng H., Caldwell M. C., Hutter D., Liu Y., Holbrook N., and Gorospe M. (2000) HuR regulates p21 mRNA stabilization by UV light. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 760–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lal A., Mazan-Mamczarz K., Kawai T., Yang X., Martindale J. L., and Gorospe M. (2004) Concurrent versus individual binding of HuR and AUF1 to common labile target mRNAs. EMBO J. 23, 3092–3102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Battelli C., Nikopoulos G. N., Mitchell J. G., and Verdi J. M. (2006) The RNA-binding protein Musashi-1 regulates neural development through the translational repression of p21WAF-1. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 31, 85–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yano M., Okano H. J., and Okano H. (2005) Involvement of Hu and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K in neuronal differentiation through p21 mRNA post-transcriptional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 12690–12699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moumen A., Masterson P., O'Connor M. J., and Jackson S. P. (2005) hnRNP K: an HDM2 target and transcriptional coactivator of p53 in response to DNA damage. Cell 123, 1065–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kechavarzi B., and Janga S. C. (2014) Dissecting the expression landscape of RNA-binding proteins in human cancers. Genome Biol. 15, R14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kim M. Y., Hur J., and Jeong S. (2009) Emerging roles of RNA and RNA-binding protein network in cancer cells. BMB Rep. 42, 125–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jiang Y., Zhu Y., Liu Z. J., and Ouyang S. (2017) The emerging roles of the DDX41 protein in immunity and diseases. Protein Cell 8, 83–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lewinsohn M., Brown A. L., Weinel L. M., Phung C., Rafidi G., Lee M. K., Schreiber A. W., Feng J., Babic M., Chong C. E., Lee Y., Yong A., Suthers G. K., Poplawski N., Altree M., et al. (2016) Novel germ line DDX41 mutations define families with a lower age of MDS/AML onset and lymphoid malignancies. Blood 127, 1017–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Polprasert C., Schulze I., Sekeres M. A., Makishima H., Przychodzen B., Hosono N., Singh J., Padgett R. A., Gu X., Phillips J. G., Clemente M., Parker Y., Lindner D., Dienes B., Jankowsky E., et al. (2015) Inherited and somatic defects in DDX41 in myeloid neoplasms. Cancer Cell 27, 658–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Irion U., and Leptin M. (1999) Developmental and cell biological functions of the Drosophila DEAD-box protein abstrakt. Curr. Biol. 9, 1373–1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Irion U., Leptin M., Siller K., Fuerstenberg S., Cai Y., Doe C. Q., Chia W., and Yang X. (2004) Abstrakt, a DEAD box protein, regulates Insc levels and asymmetric division of neural and mesodermal progenitors. Curr. Biol. 14, 138–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sohn D., Budach W., and Jänicke R. U. (2011) Caspase-2 is required for DNA damage-induced expression of the CDK inhibitor p21(WAF1/CIP1). Cell Death Differ. 18, 1664–1674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Scott D. D., and Oeffinger M. (2016) Nucleolin and nucleophosmin: nucleolar proteins with multiple functions in DNA repair. Biochem. Cell Biol. 94, 419–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Riley K. J., and Maher L. J. 3rd. (2007) p53 RNA interactions: new clues in an old mystery. RNA 13, 1825–1833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sohn D., Essmann F., Schulze-Osthoff K., and Jänicke R. U. (2006) p21 blocks irradiation-induced apoptosis downstream of mitochondria by inhibition of cyclin-dependent kinase-mediated caspase-9 activation. Cancer Res. 66, 11254–11262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Linder P., and Fuller-Pace F. V. (2013) Looking back on the birth of DEAD-box RNA helicases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1829, 750–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pause A., Méthot N., and Sonenberg N. (1993) The HRIGRXXR region of the DEAD box RNA helicase eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4A is required for RNA binding and ATP hydrolysis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 6789–6798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schmucker D., Vorbrüggen G., Yeghiayan P., Fan H. Q., Jäckle H., and Gaul U. (2000) The Drosophila gene abstrakt, required for visual system development, encodes a putative RNA helicase of the DEAD box protein family. Mech. Dev. 91, 189–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sapkota G. P., Cummings L., Newell F. S., Armstrong C., Bain J., Frodin M., Grauert M., Hoffmann M., Schnapp G., Steegmaier M., Cohen P., and Alessi D. R. (2007) BI-D1870 is a specific inhibitor of the p90 RSK (ribosomal S6 kinase) isoforms in vitro and in vivo. Biochem. J. 401, 29–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Neise D., Sohn D., Stefanski A., Goto H., Inagaki M., Wesselborg S., Budach W., Stühler K., and Jänicke R. U. (2013) The p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) inhibitor BI-D1870 prevents γ irradiation-induced apoptosis and mediates senescence via RSK- and p53-independent accumulation of p21WAF1/CIP1. Cell Death Dis. 4, e859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bourgeois C. F., Mortreux F., and Auboeuf D. (2016) The multiple functions of RNA helicases as drivers and regulators of gene expression. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 426–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Abdelhaleem M. (2004) Over-expression of RNA helicases in cancer. Anticancer Res. 24, 3951–3953 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhang Z., Yuan B., Bao M., Lu N., Kim T., and Liu Y. J. (2011) The helicase DDX41 senses intracellular DNA mediated by the adaptor STING in dendritic cells. Nat. Immunol. 12, 959–965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bates G. J., Nicol S. M., Wilson B. J., Jacobs A. M., Bourdon J. C., Wardrop J., Gregory D. J., Lane D. P., Perkins N. D., and Fuller-Pace F. V. (2005) The DEAD box protein p68: a novel transcriptional coactivator of the p53 tumour suppressor. EMBO J. 24, 543–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chao C. H., Chen C. M., Cheng P. L., Shih J. W., Tsou A. P., and Lee Y. H. (2006) DDX3, a DEAD box RNA helicase with tumor growth-suppressive property and transcriptional regulation activity of the p21waf1/cip1 promoter, is a candidate tumor suppressor. Cancer Res. 66, 6579–6588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kittler R., Pelletier L., Heninger A. K., Slabicki M., Theis M., Miroslaw L., Poser I., Lawo S., Grabner H., Kozak K., Wagner J., Surendranath V., Richter C., Bowen W., Jackson A. L., et al. (2007) Genome-scale RNAi profiling of cell division in human tissue culture cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 1401–1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nicol S. M., Bray S. E., Black H. D., Lorimore S. A., Wright E. G., Lane D. P., Meek D. W., Coates P. J., and Fuller-Pace F. V. (2013) The RNA helicase p68 (DDX5) is selectively required for the induction of p53-dependent p21 expression and cell-cycle arrest after DNA damage. Oncogene 32, 3461–3469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yang L., Lin C., Zhao S., Wang H., and Liu Z. R. (2007) Phosphorylation of p68 RNA helicase plays a role in platelet-derived growth factor-induced cell proliferation by up-regulating cyclin D1 and c-Myc expression. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 16811–16819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Botlagunta M., Vesuna F., Mironchik Y., Raman A., Lisok A., Winnard P. Jr, Mukadam S., Van Diest P., Chen J. H., Farabaugh P., Patel A. H., and Raman V. (2008) Oncogenic role of DDX3 in breast cancer biogenesis. Oncogene 27, 3912–3922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Germann S., Gratadou L., Zonta E., Dardenne E., Gaudineau B., Fougère M., Samaan S., Dutertre M., Jauliac S., and Auboeuf D. (2012) Dual role of the ddx5/ddx17 RNA helicases in the control of the pro-migratory NFAT5 transcription factor. Oncogene 31, 4536–4549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Abdul-Ghani M., Hartman K. L., and Ngsee J. K. (2005) Abstrakt interacts with and regulates the expression of sorting nexin-2. J. Cell. Physiol. 204, 210–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dardenne E., Polay Espinoza M., Fattet L., Germann S., Lambert M. P., Neil H., Zonta E., Mortada H., Gratadou L., Deygas M., Chakrama F. Z., Samaan S., Desmet F. O., Tranchevent L. C., Dutertre M., et al. (2014) RNA helicases DDX5 and DDX17 dynamically orchestrate transcription, miRNA, and splicing programs in cell differentiation. Cell Rep. 7, 1900–1913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Marcel V., Catez F., and Diaz J. J. (2015) p53, a translational regulator: contribution to its tumour-suppressor activity. Oncogene 34, 5513–5523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fontoura B. M., Atienza C. A., Sorokina E. A., Morimoto T., and Carroll R. B. (1997) Cytoplasmic p53 polypeptide is associated with ribosomes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 3146–3154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hermeking H. (2012) MicroRNAs in the p53 network: micromanagement of tumour suppression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 613–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zaccara S., Tebaldi T., Pederiva C., Ciribilli Y., Bisio A., and Inga A. (2014) p53-directed translational control can shape and expand the universe of p53 target genes. Cell Death Differ. 21, 1522–1534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tsuchiya N., Izumiya M., Ogata-Kawata H., Okamoto K., Fujiwara Y., Nakai M., Okabe A., Schetter A. J., Bowman E. D., Midorikawa Y., Sugiyama Y., Aburatani H., Harris C. C., and Nakagama H. (2011) Tumor suppressor miR-22 determines p53-dependent cellular fate through post-transcriptional regulation of p21. Cancer Res. 71, 4628–4639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Scoumanne A., Cho S. J., Zhang J., and Chen X. (2011) The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 is regulated by RNA-binding protein PCBP4 via mRNA stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, 213–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Li J., Tan J., Zhuang L., Banerjee B., Yang X., Chau J. F., Lee P. L., Hande M. P., Li B., and Yu Q. (2007) Ribosomal protein S27-like, a p53-inducible modulator of cell fate in response to genotoxic stress. Cancer Res. 67, 11317–11326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jiang Y., Zhang M., Qian Y., Xu E., Zhang J., and Chen X. (2014) Rbm24, an RNA-binding protein and a target of p53, regulates p21 expression via mRNA stability. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 3164–3175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Shu L., Yan W., and Chen X. (2006) RNPC1, an RNA-binding protein and a target of the p53 family, is required for maintaining the stability of the basal and stress-induced p21 transcript. Genes Dev. 20, 2961–2972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.