Abstract

Filamin-mediated linkages between transmembrane receptors (TR) and the actin cytoskeleton are crucial for regulating many cytoskeleton-dependent cellular processes such as cell shape change and migration. A major TR binding site in the immunoglobulin repeat 21 (Ig21) of filamin is masked by the adjacent repeat Ig20, resulting in autoinhibition. The TR binding to this site triggers the relief of Ig20 and protein kinase A (PKA)-mediated phosphorylation of Ser-2152, thereby dynamically regulating the TR-actin linkages. A P2204L mutation in Ig20 reportedly cause frontometaphyseal dysplasia, a skeletal disorder with unknown pathogenesis. We show here that the P2204L mutation impairs a hydrophobic core of Ig20, generating a conformationally fluctuating molten globule-like state. Consequently, unlike in WT filamin, where PKA-mediated Ser-2152 phosphorylation is ligand-dependent, the P2204L mutant is readily accessible to PKA, promoting ligand-independent phosphorylation on Ser-2152. Strong TR peptide ligands from platelet GP1bα and G-protein-coupled receptor MAS effectively bound Ig21 by displacing Ig20 from autoinhibited WT filamin, but surprisingly, the capacity of these ligands to bind the P2204L mutant was much reduced despite the mutation-induced destabilization of the Ig20 structure that supposedly weakens the autoinhibition. Thermodynamic analysis indicated that compared with WT filamin, the conformationally fluctuating state of the Ig20 mutant makes Ig21 enthalpically favorable to bind ligand but with substantial entropic penalty, resulting in total higher free energy and reduced ligand affinity. Overall, our results reveal an unusual structural and thermodynamic basis for the P2204L-induced dysfunction of filamin and frontometaphyseal dysplasia disease.

Keywords: filamin, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), protein folding, protein phosphorylation, thermodynamics

Introduction

Discovered four decades ago, filamin is widely known as an actin cross-linking protein (1, 2). In mammals, there are three paralogous isoforms, A, B, and C, which all have an actin-binding calponin homology domain at their N terminus, followed by 24 immunoglobulin (Ig)2 repeats, each of ≈95 amino acids. The 24th repeat links the 280-kDa monomers of filamin into a 560-kDa functional dimer. Two hinge regions susceptible to calpain cleavage are present between Ig repeats 15–16 and 23–24. The only major sequence variation among mammalian filamins is the presence of an 82-amino acid insert of unknown functional significance in filamin C at Ig20. Although filamins A and B are near ubiquitously expressed, filamin C expression is restricted to skeletal muscle (1, 2). Mouse knockout of all three filamin isoforms is lethal, but the developmental deficiencies are distinct, indicating a significant degree of specialization in function (3). In addition to their roles in actin assembly, the filamin isoforms have been shown to bind to >90 different proteins, indicating that filamin is a multifaceted protein involved in diverse biological processes (1). Cytoplasmic portions of many transmembrane proteins seem to be prime targets for filamin binding, mediating the physical linkage of these proteins with actin filaments for regulating cytoskeletal structure, cell shape, and cell migration (4, 5). Among the 24 repeats of vertebrate filamins, 7 repeats (4, 9, 12, 17, 19, 21, and 23) have a conserved “CD” groove in their immunoglobulin domain (Ig) that can accommodate an 11–13-residue-long amino acid segment of a binding partner protein (4). These ligands of filamin augment the immunoglobulin domain as a β-strand, thereby extending a β-sheet (5–9) (PDB: 2BP3, 2K9U, 2W0P, 2BRQ, and 3ISW).

Filamin A, the best characterized filamin paralog, is a known substrate for cAMP activated protein kinase (PKA) (10, 11). A variety of agents stimulate the phosphorylation at Ser-2152 of human filamin A (12–14). Non-phosphorylatable and phosphomimetic changes at this serine lead to perturbed focal adhesion formation and cell adhesion defects (15, 16). The process of Ser-2152 phosphorylation is stringently regulated by the conformation of Ig repeats 20 and 21 (17). The intramolecular binding of the N-terminal residues of Ig20 to the ligand binding site on Ig21 creates autoinhibition that prevents Ig21 binding to external ligands (18) (PDB 2J3S). The binding of ligands relieves autoinhibition, generating a conformation compatible as a substrate for PKA-mediated phosphorylation (17). This mechanism is a unique example of substrate shape-dependent phosphorylation by a kinase (17) (Fig. 1A). In other words, the competent substrate selects the kinase rather than the activated kinase binding a preferential substrate, a novel paradigm in biological signaling mechanisms. The intramolecular nature of autoinhibition means that ligands that bind Ig21 tightly can displace the Ig20 segment to potently promote phosphorylation at Ser-2152. In an analogous manner, cytoplasmic segments of many GPCRs are also very tight filamin-binding partners (19). These peptide ligands are predominantly part of a conserved intracellular helix in GPCRs that could accelerate PKA-mediated Ser-2152 phosphorylation in vitro. Consistent with this prediction, it was found that GPCR agonist stimulation enhances this Ser-2152 phosphorylation, implying a close physical contact between the GPCR and filamin (19). Although numerous studies had recognized filamin as a partner of GPCRs, filamin was thought to be more of an inert scaffolding protein in these signaling complexes (20–22). Bioinformatics studies now predict that a majority of GPCRs have segments that potentially bind filamin, and such binding may play crucial role in GPCR signaling (19).

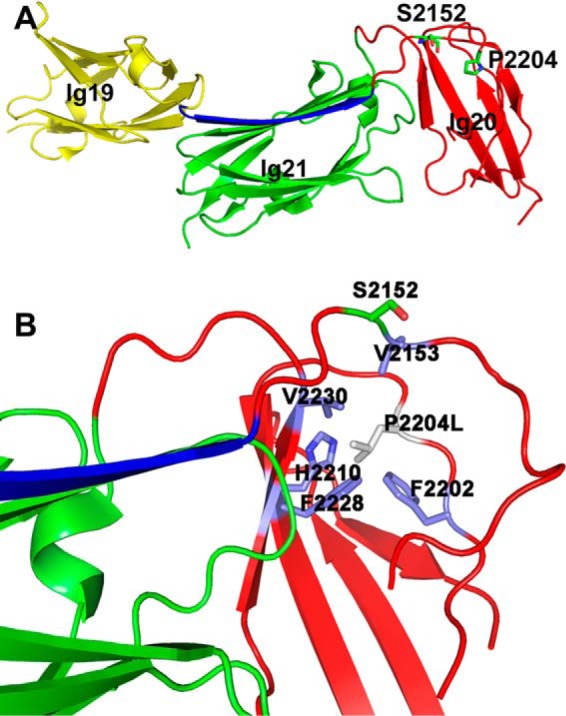

Figure 1.

Location and residues around Pro-2204 in filamin A structure. A, crystal structure of autoinhibited Ig19–21 from filamin A (PDB 2J3S). The segment of Ig20 occluding Ig21 ligand binding site is shown in blue. The Pro-2204 side chain is buried in the Ig20 segment and is proximal to the Ser-2152 phosphosite. B, substitution of Pro-2204 into leucine causes some steric clash with surrounding residues (labeled) and likely destabilizes Ig20.

Given that filamin binds a variety of proteins regulating key cellular functions, it is not surprising that both null and specifically clustered mutations in all three filamin genes were found to lead to many disorders of the brain, heart, muscle, and skeleton (23). The location of FLNA on the X-chromosome leads to severe phenotypes or lethality in males for many of the reported mutations (24–26). The biochemical and molecular basis for the mutant phenotypes remains elusive and have only been explored in a few cases. For example, the substitutions E254K (filamin A), W148R (filamin B), and M202V (filamin B) in the second calponin homology domain of the actin-binding region in filamin A all conferred gain of function properties with increased affinity for actin (27, 28). Filamin Ig23, a class A repeat (4), harbors mutations that lead to frontometaphyseal dysplasia (FMD) and periventricular nodular heterotopia due to missense and in-frame deletions (29, 30). The deletion mutants of Ig23 were shown to be defective in their rheological properties and binding to the protein FilGAP (31). However, the disease origins of L2439M mutant in Ig23 are still unclear (31). In this paper, using recombinant and purified filamin fragments, we undertook detailed structural and biochemical studies on a disease causing P2204L mutation (24) that causes FMD, a disorder involving abnormalities in skeletal development. Our analyses revealed an unusual structural and thermodynamic basis for the P2204L mutation with defects in autoinhibition, ligand binding, and Ser-2152 phosphorylation, thus providing crucial clues for understanding the molecular pathogenesis of FMD.

Results

P2204L mutant adopts a conformationally dynamic molten globule-like state

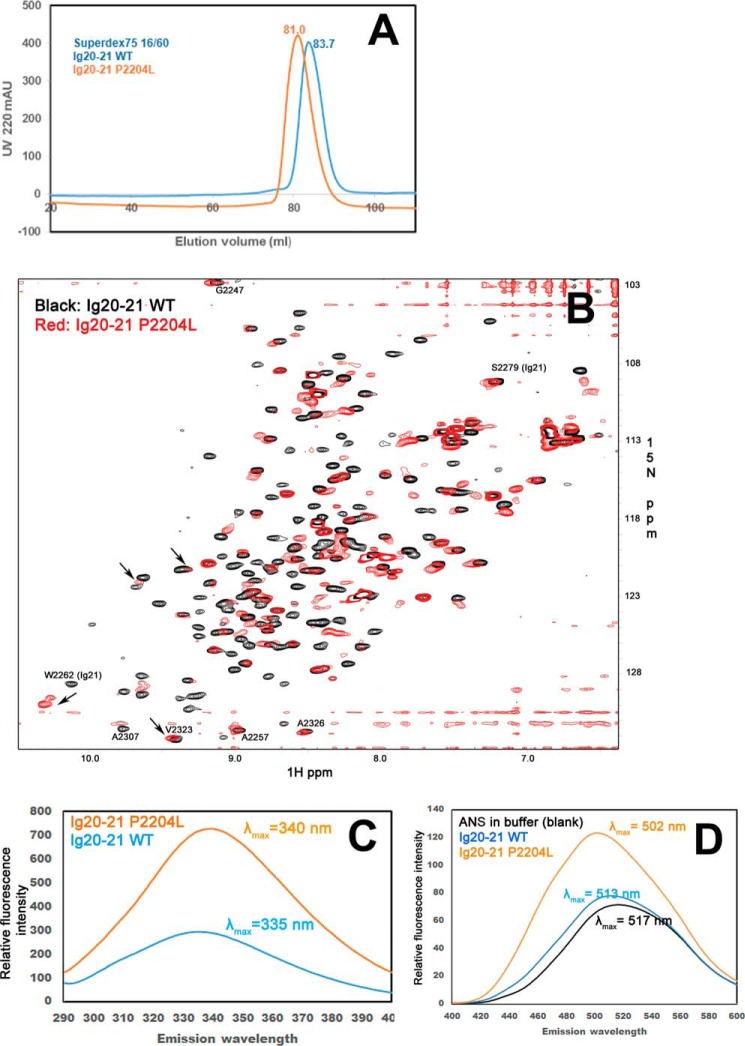

Fig. 1A displays the crystal structure (18) of filamin Ig19–21 (PDB 2J3S) containing the autoinhibitory unit Ig20–21, where the FMD disease mutation site Pro-2204 is located in a long loop of Ig20 far away from the autoinhibited interface yet buried in a hydrophobic core of the Ig20 domain involving Val-2153, Phe-2202, Phe-2228, and Val-2230. Molecular modeling indicates that although the mutation of Pro into Leu at 2204 maintains the hydrophobic feature, the long side chain of Leu would cause a minor steric clash with some of these hydrophobic residues including Phe-2202, Phe-2228, Val-2230, and also a polar residue His-2210 (Fig. 1B), thus potentially perturbing the local folding of the protein. To evaluate this prediction, we made the minimal double domain construct Ig20–21, that has no ligand binding interference with the neighboring Ig19 or Ig23. First, we compared the gel-filtration elution profiles of the purified Ig20–21 WT with that of the disease-causing mutant P2204L under identical conditions using a Superdex75 size exclusion column. As shown in Fig. 2A, the mutant eluted as a single peak, 2.7 ml, ahead of the WT, indicating a greater radius with somewhat more elongated shape. The single peak at 81 ml demonstrates that the mutant is clearly not in an aggregated form but is structurally perturbed. To gain further insight into the folding property of the mutant, we subjected the 15N-labeled WT and mutant Ig20–21 to an NMR-based HSQC experiment (Fig. 2B). The WT Ig20–21 (in black, Fig. 2B) is well folded given the widely dispersed uniform backbone amide peaks in the spectrum. However, under identical conditions the amide peaks of the mutant P2204L are substantially broadened. A few highly downfield-shifted weak signals (>9 ppm) were observed in positions corresponding to folded WT Ig20–21 (Fig. 2B), yet the line-broadened spectrum is clearly incompatible with a single folded protein like the WT. The mutant is not in a denatured state as its spectrum did not collapse into a narrow 8–9-ppm region on the 1H axis with characteristic overlapping sharp peaks. Rather, the line-broadened spectrum and somewhat more voluminous shape (based on Fig. 2, A and B) are consistent with a conformationally fluctuating partially folded intermediate or a molten globule. Despite the mutation being in Ig20, Ig21 is affected as exemplified by the significant shift of W2262 side chain amide, suggesting that the mutated Ig20 still engages with Ig21 but in a different fashion.

Figure 2.

Anomalous shape and spectra of the Ig20–21 P2204L mutant. A, size exclusion profile of the WT Ig20–21 and the P2204L mutant Ig20–21 on a Superdex75 column under identical conditions. mAU, milliabsorbance units. B, 15N HSQC of the WT Ig20–21(0.1 mm, 8 scans, black) and the P2204L mutant Ig20–21 (0.1 mm, 64 scans, red). The side chain of Trp-2262 is marked to show that Ig21 is disturbed by the mutant. Note that despite eight times more scans, the mutant still exhibits the spectrum with broadened signals, demonstrating that the mutant is in dynamic conformational exchange. C, intrinsic fluorescence of 5 μm Ig20–21 WT and the P2204L mutant using excitation at 278 nm showing the red shift of the fluorescence emission in the mutant. D, extrinsic ANS fluorescence of 5 μm Ig20–21 WT and the P2204L mutant in 50 molar excess (250 μm) ANS using excitation at 380 nm. The mutant P2204L has enhanced emission intensity, and the emission maximum is now at 502 nm, whereas the emission maximum for the WT is 513 nm.

Perturbed intrinsic fluorescence of a protein dominated by tryptophan residues is another measure of the folded state of the protein (32–34). The Ig20–21 construct has a single tryptophan residue at position 2262, and we recorded the fluorescence emission spectra by exciting the tryptophan at 278 nm, the absorption maximum for both the WT and the P2204L mutant at 5 μm protein concentration in buffer conditions identical to that used for gel filtration and HSQC-NMR above. The emission intensity for the mutant was significantly higher, and the emission maximum (λmax) was red-shifted to 340 nm from 335 nm in the WT (Fig. 2C). This tryptophan is located in Ig21 and is >20 Å from the P2204L mutation site. This result provides strong evidence that the mutant has undergone a substantial global structural transition as opposed to a local change around the site of the mutation. To rule out the contribution of phenylalanine and tyrosine residues to the emission spectra, we recorded the fluorescence emission by exciting the protein at 295 nm, and this experiment too resulted in similar red shifted emission for the P2204L mutant (supplemental Fig. S1), furthering the notion of a molten globule.

To further gain insight into the altered folding state of the mutant, we performed 8-anilino-1-naphthalenesulfonic acid (ANS) binding experiment. The enhanced fluorescence from ANS binding to protein is a widely used sensitive marker for differentiating molten globule from folded/unfolded states of proteins (35, 36). ANS does not bind appreciably to native or totally unfolded proteins but binds well to partially folded/molten globule state with hydrophobic patches exposed (35, 36). We probed ANS binding to Ig20–21 WT and the P2204L mutant using excitation at 380 nm and recording the emission from 400–600 nm using a 50 molar excess of ANS (5 μm protein and 250 μm ANS). Fluorescence enhancement was minimal in the WT when compared with the ANS only buffer control (Fig. 2D). The mutant though had much higher fluorescent intensity, and the emission max was blue-shifted to 502 nm (Fig. 2D). This feature is consistent with a molten globule state as documented previously (35). Note that control ANS experiments in denaturant, 6 m guanidine hydrochloride, leads to a loss of these emergent fluorescent features leading to uniform spectral outputs (supplemental Fig. 2). Overall, all the four above experiments, size exclusion, HSQC-NMR, intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence, and extrinsic ANS fluorescence, together provide strong evidence that the mutant P2204L Ig20–21 is likely a molten globule.

P2204L mutant is readily phosphorylated at Ser-2152 without ligand

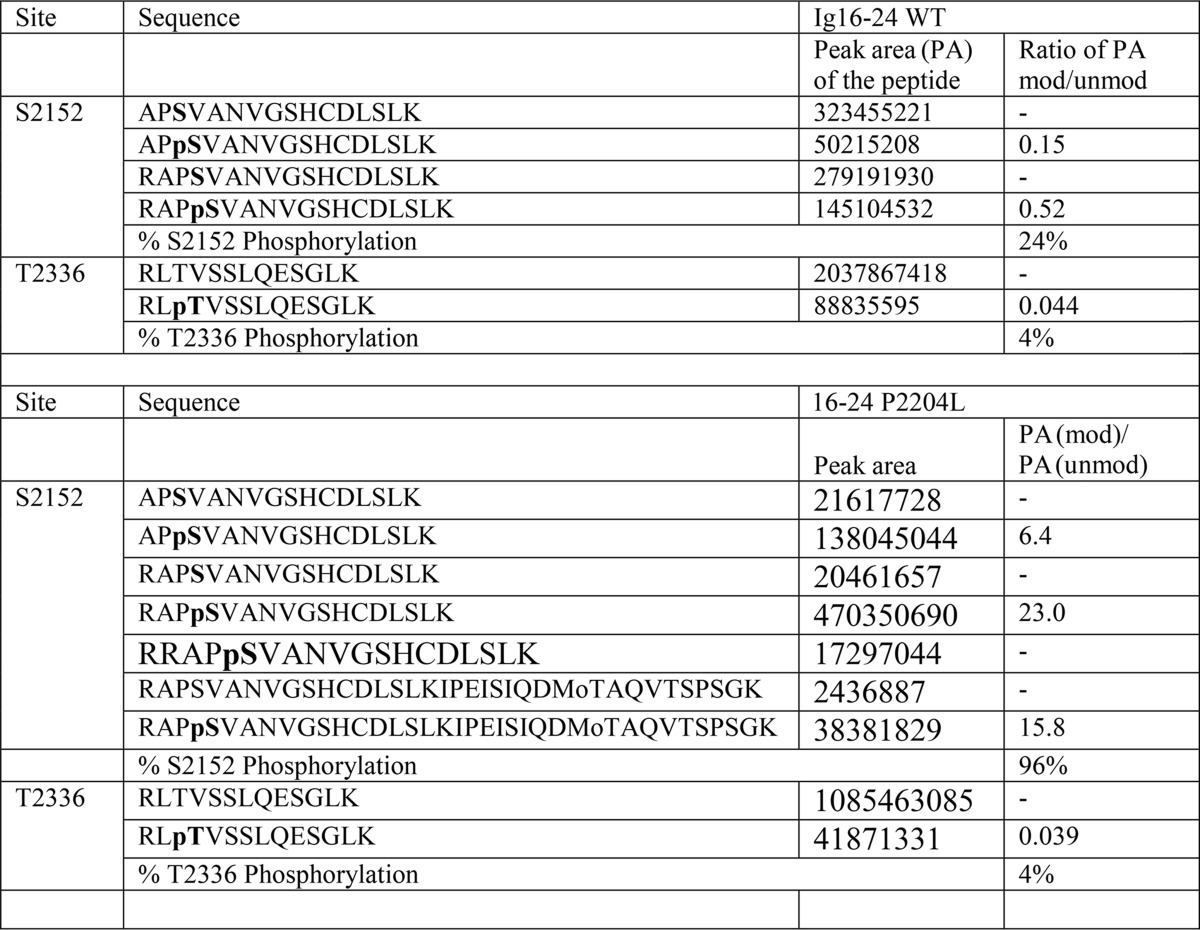

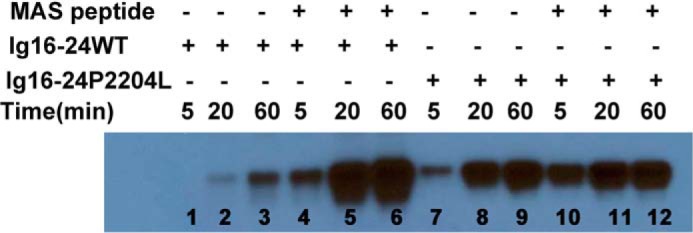

Because previous studies showed that ligand binding to Ig21 relieves Ig20 causing a global conformational change and enhanced PKA-mediated phosphorylation on Ig20 Ser-2152 (17), we first wondered how the P2204L-induced destabilization of Ig20 would impact on the Ser-2152 phosphorylation. As done previously (17), we used the dimeric Ig16–24 construct encompassing the entire rod 2 domain of filamin A to test the phosphorylation effect. Interestingly, unlike WT, which had minimal phosphorylation without ligand binding due to the autoinhibited conformation, the mutant Ig16–24 was readily phosphorylated in the absence of ligand (Fig. 3, compare lanes 1–3 with lanes 7–9). As demonstrated earlier (19), the tight binding MAS GPCR peptide enhanced Ser-2152 phosphorylation of Ig 16–24 (Fig. 3, compare lanes 1–3 with lanes 4–6), but the MAS peptide led to saturation of phosphorylation at a much earlier time point in the P2204L mutant (Fig. 3, compare P2204L lanes 10–12 with lanes 1–9). The PKA reaction at the 1 h time point without the added MAS peptide was subjected to quantitative mass spectroscopy by protease digestions to conform the results from Western blotting. Table 1 summarizes the results from mass spectrometry and confirms that the P2204L mutant is at least four times (24% versus 96%) more susceptible to PKA phosphorylation than the WT Ig16–24 in the absence of MAS ligand. The Thr-2336 residue in Ig22 serves as an internal control, and this low-level phosphorylation does not change between the WT and the mutant P2204L filamin A Ig16–24 (Table 1). The unchanging Thr-2336 phosphorylation also hints that the P2204L mutant leads to local and limited changes in Ig20–21 and does not lead to global changes in filamin structure. These data indicate that the mutation-induced dynamic and partially unfolded conformation of Ig20 in Ig16–24 became readily accessible to PKA for catalysis unlike the Ig20 in WT Ig16–24.

Figure 3.

Elevated susceptibility of the P2204L mutant to PKA-mediated phosphorylation in the dimeric Ig16–24 C-terminal filamin A. Notice that the mutant phosphorylation is the ligand (MAS)-independent contrasting to the ligand-dependent phosphorylation of the WT.

Table 1.

Degree of phosphorylation in the Ig16–24 WT and mutant P2204L proteins

Peak area is the quantitation of elution peaks of the peptides from liquid chromatography entering the mass spectrometer after protease digestion of Ig16–24. The phosphorylated protein samples used were from the 1 h time point of the WT and mutant protein without added ligand (Fig. 3).

P2204L mutant has impaired/reduced capacity to bind ligand

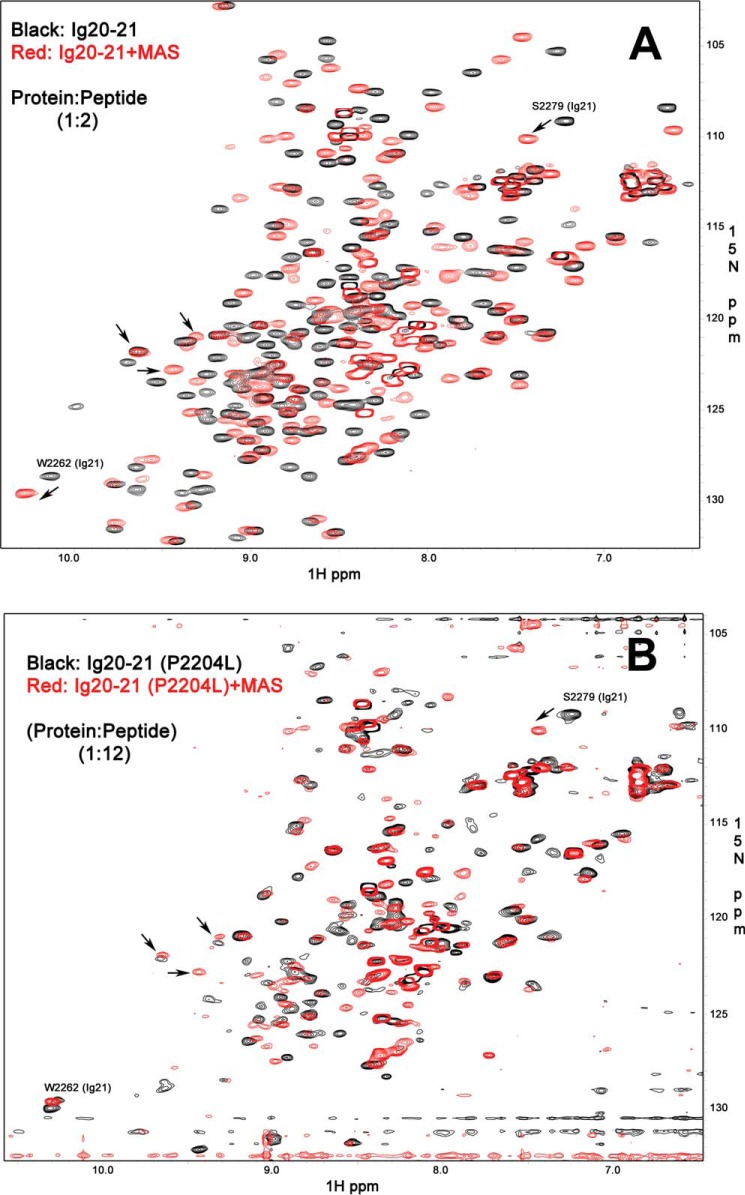

Next, we wondered how ligands would bind to the P2204L mutant. Although the mutation site is not directly involved in the autoinhibitory interface (see Fig. 1), the mutation-induced formation of the partially folded intermediate of Ig20 should in principle destabilize its engagement with Ig21, including the autoinhibitory interface. The tightest ligand (4) for filamin repeats is GP1bα, and this peptide caused precipitation of the Ig20–21 WT protein and hence could not be used for comparative studies. We, therefore, used the MAS peptide for examination, which has slightly reduced affinity as compared with GP1bα (19) but did not lead to protein loss by precipitation. Surprisingly, although the MAS peptide led to widespread changes in the WT Ig20–21 spectrum characteristic of tight binding and relief of the autoinhibition (Fig. 4A), the P2204L mutant showed no signal narrowing/recovery of the spectrum upon the addition of the strong ligand (Fig. 4B). If MAS effectively displaced Ig20 to bind Ig21, we would have at least observed recovering signals of Ig21 bound to MAS despite the molten globule state of Ig20. Some broadened peaks are visible, such as the characteristic Ser-2279 that is near the ligand binding groove of Ig21. They are shifted upon the addition of MAS peptide, indicating that the ligand still binds to the mutant though much weaker. However, the shifts of these peaks are less than those of WT (Fig. 4B versus Fig. 4A). These combined results suggest that unlike WT Ig20–21, the mutant has impaired or reduced capacity to bind the ligand.

Figure 4.

Comparison of ligand binding to WT and mutant filamin. A, 15N HSQC of the WT Ig20–21 in the free form (0.2 mm WT protein, 8 scans, black) and with the bound MAS peptide (0.2 mm protein with 0.4 mm MAS peptide, 8 scans, red). B, 15N HSQC of the mutant P2204L Ig2021 in the free form (0.1 mm P2204L mutant, 64 scans, black) and with the bound MAS peptide (0.1 mm protein with 1.2 mm MAS peptide, 64 scans, red). Both proteins bind the MAS peptide as seen by the appearance of multiple new peaks, but the mutant protein has much broadened signals and does not recover the features of single conformational class upon ligand binding. Some peaks in >9 ppm range are marked by arrows to show that the protein has folded features but under dynamic intermediate exchange (molten globule). Such molten globule still binds to ligand as shown by characteristic shift of Ser-2279 in up-field, but the shift is less than that of WT (Fig. 4A), suggesting weaker binding.

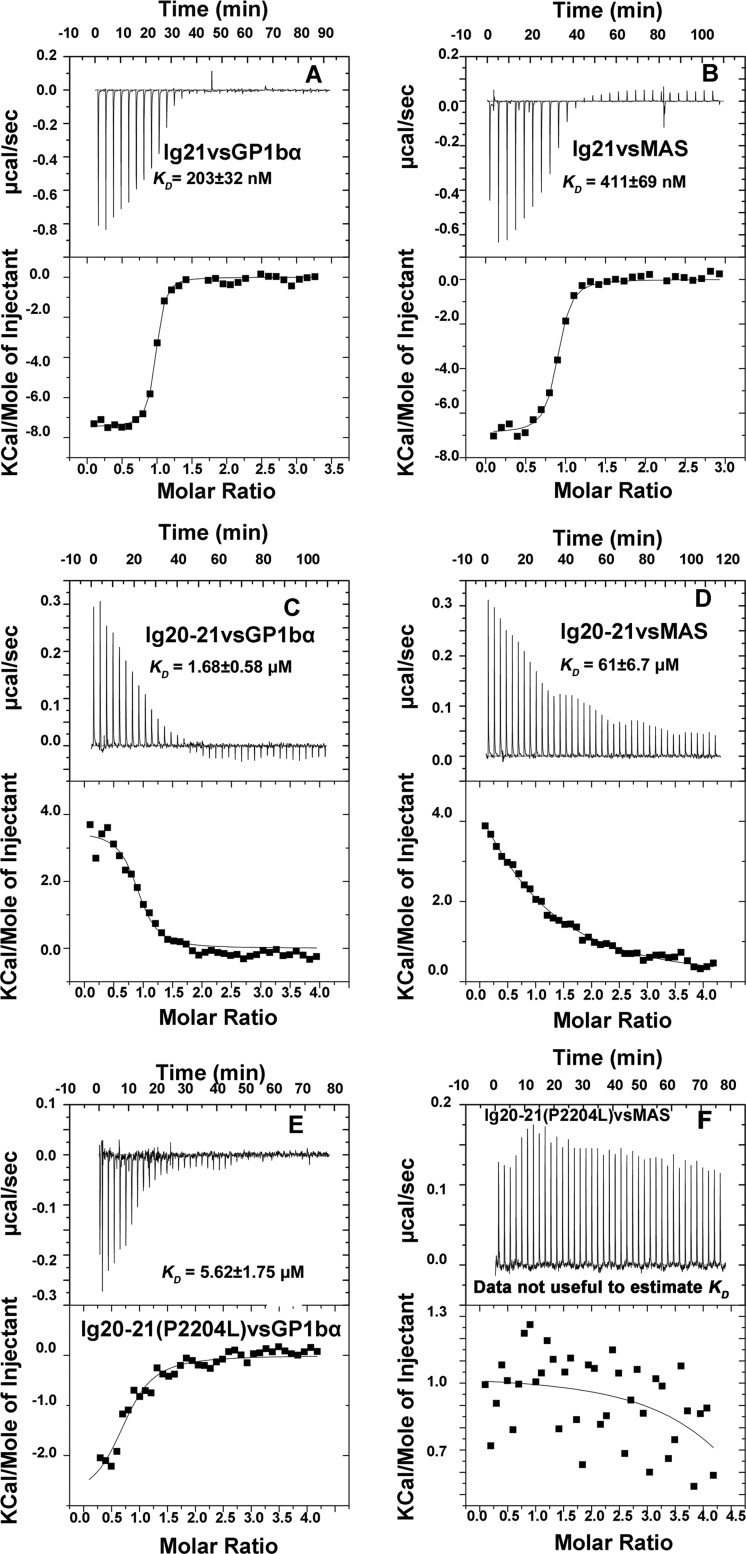

Given the above data showing that the Ig20–21 mutant P2204L is much less responsive to ligand binding, we decided to perform quantitative ligand binding experiments using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). We first compared the energetics of the isolated Ig21 with that of the autoinhibited Ig20–21 using the well characterized GP1bα and MAS peptides. Interestingly, although the isolated Ig21 binding of GP1bα (Fig. 5A) and MAS (Fig. 5B) were enthalpically favorable (exothermic with a large negative enthalpy confirming our earlier results), the ligand binding to autoinhibited Ig20–21 was enthalpically unfavorable (endothermic) and entropy-driven (Fig. 5, C and D, and Table 2). Autoinhibition led to a reduction in the affinity of ≈8 times for GP1bα and ≈140 times for the MAS peptide (Table 2) and reversed the energetics of binding. Contrasting to the WT Ig20–21, P2204L destabilized Ig20, which made GP1bα binding enthalpically favorable (exothermic) but with substantial entropic penalty likely due to the fluctuating nature of the Ig20 mutant before ligand binding (much smaller entropic change than that of WT; see Table 2). As a net result, the total free energy of the GP1bα binding for the mutant is higher than the WT, which led the reduced ligand binding affinity for the mutant (Fig. 5E and Table 2), which is consistent with the NMR data (Fig. 4B). The same trend was observed for MAS ligand binding to WT versus mutant Ig20–21 (Fig. 5F and Table 2), where the P2204L mutant shows weak endothermic binding by ITC. This weak endothermic binding probably reflects some residual binding still in play for weaker ligands like MAS. Binding of the MAS peptide in itself is consistent with the NMR data in Fig. 4B. However, an accurate affinity estimate was not possible with this weak ITC data.

Figure 5.

Isothermal titration calorimetry profiles of ligand binding to WT and mutant. A, Ig21 binding to GP1bα peptide (exothermic). B, Ig21 binding to MAS peptide (exothermic). C, Ig20–21 binding GP1bα peptide (endothermic). D, Ig20–21 binding to MAS peptide (endothermic). E, P2204L Ig20–21 binding to GP1bα peptide (exothermic). F, P2204L Ig20–21 binding to MAS peptide. See Table 2 for details of the energetics.

Table 2.

Comparison of the thermodynamic parameters (kcal/mol) of Ig21 and Ig20–21 binding to peptides

N is the number of binding sites per protein molecule; KD is the dissociation constant; ΔG is the total change in free energy; ΔH is the change in enthalpy; ΔS is the change in entropy; T is the absolute temperature. All numbers use the Gibbs free energy equation ΔG = ΔH − TΔS. NA, KD not accurately analyzable due to very weak binding.

| Experiment | N | KD | ΔG | ΔH | ΔS | TΔS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kcal/mol | kcal/mol | kcal/mol | kcal/mol | |||

| Ig21 + GP1bα | 0.94 | 203 ± 32 nm | −9,279 | −7458 ± 72 | 6.01 | 1,821 |

| Ig20–21 + GP1bα | 0.89 | 1.68 ± 0.58 μm | −8,011 | 3503 ± 154 | 38.00 | 11,514 |

| Ig20–21(P2204L) + GP1bα | 0.76 | 5.62 ± 1.75 μm | −7,283 | −2890 ± 339 | 14.50 | 4,394 |

| Ig21 + MAS | 0.86 | 411 ± 69 nm | −8,853 | −6893 ± 92 | 6.47 | 1,960 |

| Ig20–21 + MAS | 0.79 | 61 ± 6.7 μm | −5,859 | 10,260 ± 1,596 | 53.10 | 16,089 |

| Ig20–21(P2204L) + MAS | NA | >200 μm | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Discussion

As a major cytoskeletal protein, filamin has been extensively studied for its binding to target proteins. Filamin has two characteristic binding features; one is actin binding via the calponin homology domains at the N terminus and the other is binding to cytoplasmic regions of multiple transmembrane receptors, notably integrins and GPCRs, via seven homologous class A Ig repeats (repeat 4, 9, 12, 17, 19, 21, and 23) (4). Many disease mutations have been found in filamin, and a majority of them occur in these two types of binding regions or regions surrounding them. However, only a few very limited mutations, which are unrelated to the autoinhibition, have been biochemically and biophysically studied. The mutations W148R and M202V in filamin B that cause autosomal dominant atelosteogenesis were shown to be located in the CH2 domain of the actin-binding site of filamin B, which lead to tighter actin binding and hence the likely gain of function phenotype (27). The G2593E (Ig24) mutant in filamin A, which causes a mild form of periventricular heterotopia, was indicated to arise from filamin dimerization defect (25). Here we have undertaken the first detailed structural and biochemical analyses of frontometaphyseal dysplasia mutation P2204L in Ig repeat 20 of filamin A. The mutation site is proximal to the phosphorylation site Ser-2152. On the other hand, although Ig20 is involved in autoinhibition, the mutation site is quite distant from the autoinhibitory interface (Fig. 1A). The binding of ligand migfilin or GP1bα to Ig21 makes the protein more flexible and adopt a distinct conformation (17, 37). Our observations were interesting as the mutation affected both filamin autoinhibition and phosphorylation in an opposite and uncoupled manner, unlike the WT filamin.

Our molecular modeling analysis indicated that P2204L might induce a hydrophobic core collapse due to the steric clash of the Leu side chain with the hydrophobic core residues and thus may lead to the formation of a partially folded intermediate at Ig20. Due to the packing of Ig20 with Ig21, as in the autoinhibited conformation, this mutation in Ig20 perturbed the overall structural integrity of Ig20–21, as implicated by the substantially broadened NMR signals (Fig. 2B) and increased hydrodynamic volume (Fig. 2A). The results hinted that the destabilizing mutation likely induced partial unfolding of Ig20–21, resulting in a molten globule-like state. Although the broadened NMR peaks may alternatively reflect interchanging fully folded and totally unfolded states on the millisecond time scale, this possibility was eliminated by our subsequent ANS-binding experiments. ANS is known not to bind well to either fully folded or totally unfolded protein (35, 36), and this was reflected in our studies (Fig. 2D and supplemental Fig. S2) with the WT Ig20–21. By contrast, the P2204L mutant in phosphate buffer bound ANS robustly (Fig. 2D). If the mutant were to only sample folded and unfolded states in the millisecond timescale, ANS would not bind to the protein. Consistently the red shift of the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence in the mutant clearly hints that the mutant is in a transition between folded and unfolded states (32–34). Thus, intrinsic tryptophan and extrinsic ANS fluorescence experiments gave further evidence that the conjoined domains 20–21 is likely a molten globule(Fig. 2, C and D) in the mutant filamin.

Unlike WT filamin, which requires the ligand binding to produce a conformationally unrestricted Ig20 to access PKA for phosphorylation catalysis, the mutant itself was readily phosphorylated without ligand, apparently due to the conformational plasticity of the mutant. Such altered capacity of the mutant for phosphorylation likely alters filamin function during cell adhesion and migration and relates to the pathogenic mechanism leading to FMD. Because of the destabilization of Ig20 by P2204L, which would loosen/disturb the Ig20 contact with Ig21, we then thought that ligand binding to the mutant would be enhanced due to the potentially weakened autoinhibition. However, to our surprise, ITC studies demonstrated that the overall KD of the mutant to ligand was reduced by >3 fold as compared with the WT filamin (Table 2). Consistently, the potent MAS ligand was unable to recover the broadened NMR signals especially for Ig21, indicating the reduced capacity of MAS to relieve the autoinhibition of the filamin mutant. Detailed thermodynamic analysis revealed that although the mutation did make autoinhibited filamin enthalpically favorable (exothermic) for ligand binding (with the GP1bα peptide, contrasting to the WT filamin, which was enthalpically unfavorable, i.e. endothermic, see Table 2), the mutant became more entropically unfavorable for ligand binding due to the mutation-induced conformational and structural liability. This is the likely reason for the broadening/disappearance of the Ig21 peaks from the HSQC spectra for the mutant Ig20–21. By contrast, our earlier results with a splice form of filamin, where the autoinhibition segment is completely missing, revealed no signal broadening for Ig21 (38, 39). This Ig20 mutant lacks 42 amino acids from Ig20 including the β-strand that blocks Ig21 CD groove (38). Thus, through entropic penalty, the P2204L mutant strengthens the autoinhibition from a thermodynamic point of view. This is clear from the ITC profile of the mutant as it binds GP1bα 3 times weaker than the WT (KD 5.6 μm versus 1.68 μm). The same trend is true for MAS ligand, which binds to Ig20–21 at 61 μm, but more weakly to the mutant P2204L (KD unanalyzable due to the weak affinity, likely >200 μm). Given the negligible affinity of the MAS GPCR peptide to the P2204L mutant, other cellular ligands like integrins and migfilin binding to this FMD mutant at Ig21 will be insignificant. This weakened binding of the conjoined repeats to ligands is likely to upset mechanotransduction properties of the entire filamin molecule. This may weaken integrin-extracellular matrix adhesion strength as shown in a recent fibroblast-specific filamin knock-out study (40).

In summary, unlike WT filamin, in which the phosphorylation at Ser-2152 is strongly enhanced with the release of the autoinhibition by ligand binding, the Pro-2204 mutant is readily phosphorylated without ligand, whereas the autoinhibition is “strengthened,” as compared with WT filamin; hence, a weakening of ligand binding in the mutant. Using combined NMR and ITC approaches, we obtained structural and thermodynamic insight into these unusual defects. Mindful of the observation that clustered mutations in the actin binding domain and in repeats 9–11 and 15–16 also produce FMD (30), this study may serve as a foundational step for elucidating the key signaling functions mediated by filamin A that comprises the fundamental mechanisms leading to a range of filamin-related skeletal diseases. In particular, the altered capacity of filamin autoinhibition by the mutation may affect the strength and dynamics of the extracellular matrix-actin linkage in relation to cell stiffness, adhesion strength (40), etc., which are directly involved in muscle/bone development and thus contribute to the FMD.

Experimental procedures

Proteins and peptides

Ig repeats 20–21 (Gly-2136–Ser-2329) of human filamin A (uniprot; P21333) was generated by truncating the larger Ig16–24 construct using the QuikChange lightning mutagenesis kit, and the P2204L mutant within Ig20–21 and Ig 16–24 was generated using the QuikChange lightning mutagenesis kit (catalogue #210518) form Agilent Technologies. All constructs were DNA sequenced and had no untoward mutations. Proteins were expressed as glutathione S-transferase fusions and purified as described earlier (4). Very tight Ig21-binding peptides derived from human platelet protein GP1bα (uniprot; P07359, FLRGSLTFRSSLFLWVRPNGRV) and human MAS, a constitutively active GPCR (uniprot; P04201, KKKRFKESLKVVLTRAFK) were synthesized by the Biotechnology core of the Lerner research Institute at the Cleveland Clinic.

Molecular modeling

The A subunit in the Ig19–21 filamin A crystal structure (PDB 2J3S) was used to assess the effect of the P2204L mutation. The mutagenesis tool of the PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.8 Schrödinger, LLC) graphics system was used to change the proline to a leucine, and the clashes generated by the side chain of introduced leucine were noted.

In vitro PKA phosphorylation assay

The kinase phosphorylation assay using 10 μm Ig16–24 WT and the P2204L mutant Ig16–24 as substrates was performed in buffer containing 50 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, and 500 μm ATP. 50 μm MAS peptide was used to release autoinhibition. For each 100-μl reaction, 1000 units of murine PKA (New England BioLabs) was used. Filamin Ser-2152 phosphorylation was detected by Western blotting using polyclonal phospho-filamin A antibody #4761 from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA).

Mass spectrometry

The 1-h assay product from the PKA phosphorylation assay was used to assess and compare the degree of Ser-2152 phosphorylation in the Ig16–24 wild type and P2204L mutant filamin C terminus. Bands were excised from Coomassie-stained gels, and this protein was reduced, alkylated, and digested with trypsin. The digests were analyzed by capillary column LC-tandem MS, and the collision-induced dissociation spectra were searched against filamin sequences. The WT and mutated peptide fragments was precisely identified in the samples. Chromatograms were plotted for the unmodified and modified Ser-2152- and Thr-2336-containing peptides, and the peak area for each of these peptides was determined. These peak areas were used to calculate both the peak area ratio (modified/unmodified) and the % phosphorylation.

Size exclusion chromatography

100 μl of purified recombinant Ig20–21 WT and P2204L mutant at a concentration of 5 mg/ml was subjected to size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex S75 1660 column (GE Healthcare) on an AKTA protein purification system from GE Healthcare under identical buffer (25 mm sodium phosphate (pH 6.4), 5 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT) and flow conditions (1 ml/min).

Nuclear magnetic resonance

15N-Labeled proteins were subjected to HSQC-NMR using a cryo-cooled Bruker 600-MHz machine at a concentration of 0.1 mm or 0.2 mm. The protein was extensively buffered with 25 mm sodium phosphate (pH 6.4), 5 mm NaCl, and 1 mm DTT. The MAS peptide was added at 2 times in excess of the protein for the WT Ig20–21, and 8 scans were recorded. For the P2204L mutant the MAS peptide was added 12 times in excess of the protein. Spectra were recorded in identical conditions. The pH of the protein samples overlaid were within 0.03 units, and the spectra were recorded at 30 °C. Spectra were processed and analyzed using nmrPipe and NMRView (41).

For ANS binding to Ig20–21 and intrinsic fluorescence, ANS (#10417) was purchased from Sigma and was of >97% purity. Fluorescence measurements was performed at room temperature for ANS binding, and native fluorescence was done on a Hitachi F-2500 fluorescence spectrophotometer in the same buffer conditions used for size exclusion chromatography and HSQC-NMR. The excitation and emission slit widths were 10 nm. A 50× excess of ANS over protein (WT Ig20–21 or P2204L Ig20–21) was used (5 μm: 250 μm) in the measurements. Excitation was induced at 380 nm, and fluorescence was recorded between 400 and 600 nm. Control experiments were performed with completely unfolded protein in 6 m guanidine hydrochloride in identical buffer conditions to rule out nonspecific effects. Native tryptophan fluorescence emission was measured between 290 and 400 nm by exciting the protein (5 μm in conditions identical to ANS binding) at 278 nm. The wild type and the mutant Ig20–21 had the same absorption maximum. The results were confirmed by experiments using 295-nm excitation as well. All the fluorescence spectra were recorded at room temperature.

Isothermal calorimetry

iTC200 calorimeter from Malvern instruments was used for measuring the affinities of peptide binding to Ig repeats of filamin. The buffer and temperature conditions were precisely matched to those used in the HSQC NMR experiments. The syringe concentration of the peptide was 1 mm, and the Ig repeat concentration in the cell chamber was 50 μm. Ligand was injected at 1-μl increments at a stirring speed of 750 rpm. Binding affinities were calculated using the associated origin software.

Author contributions

S. S. I. conceived the mutants and designed and conducted most of the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the paper. K. D. made the mutants, purified the recombinant proteins, and conducted some experiments. S. P. R. provided disease expertise and suggested experiments. J. Q. designed the experiments and supervised the project. S. S. I. and J. Q. wrote the paper.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Peptides were synthesized by the Molecular Biotechnology Core at the Lerner Research Institute (Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH). We acknowledge Dr. Smarajit Bandyopadhyay and Weizhen Shen for excellent peptide preparations. We thank Dr. Belinda Willard of the Proteomics and Metabolomics laboratory for help with mass spectrometry (NIH shared instrument Grant 1S10RR031537-01). We also sincerely thank David Schumick from the Center for Medical Art and Photography at the Cleveland Clinic (Cleveland, OH) for help with graphic illustrations. We thank Dr. Mohammed Mahfuzul Haque and Yue Dai of the Department of Pathobiology for help with use of the fluorimeter.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants GM062823 and P01HL073311 (to J. Q.). The authors have no conflict of interest with the contents of the article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- Ig21

- immunoglobulin repeat 21

- GPCR

- G-protein coupled receptor

- FMD

- frontometaphyseal dysplasia

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum correlation

- ANS

- 8-anilino-1-naphthalenesulfonic acid.

References

- 1. Nakamura F., Stossel T. P., and Hartwig J. H. (2011) The filamins: organizers of cell structure and function. Cell Adh. Migr. 5, 160–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. van der Flier A., and Sonnenberg A. (2001) Structural and functional aspects of filamins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1538, 99–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhou A. X., Hartwig J. H., and Akyürek L. M. (2010) Filamins in cell signaling, transcription and organ development. Trends Cell Biol. 20, 113–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ithychanda S. S., Hsu D., Li H., Yan L., Liu D. D., Liu D., Das M., Plow E. F., and Qin J. (2009) Identification and characterization of multiple similar ligand-binding repeats in filamin: implication on filamin-mediated receptor clustering and cross-talk. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 35113–35121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nakamura F., Pudas R., Heikkinen O., Permi P., Kilpeläinen I., Munday A. D., Hartwig J. H., Stossel T. P., and Ylänne J. (2006) The structure of the GPIb-filamin A complex. Blood. 107, 1925–1932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ithychanda S. S., Das M., Ma Y. Q., Ding K., Wang X., Gupta S., Wu C., Plow E. F., and Qin J. (2009) Migfilin, a molecular switch in regulation of integrin activation. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 4713–4722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lad Y., Jiang P., Ruskamo S., Harburger D. S., Ylänne J., Campbell I. D., and Calderwood D. A. (2008) Structural basis of the migfilin-filamin interaction and competition with integrin β tails. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 35154–35163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kiema T., Lad Y., Jiang P., Oxley C. L., Baldassarre M., Wegener K. L., Campbell I. D., Ylänne J., and Calderwood D. A. (2006) The molecular basis of filamin binding to integrins and competition with talin. Mol Cell. 21, 337–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smith L., Page R. C., Xu Z., Kohli E., Litman P., Nix J. C., Ithychanda S. S., Liu J., Qin J., Misra S., and Liedtke C. M. (2010) Biochemical basis of the interaction between cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator and immunoglobulin-like repeats of filamin. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 17166–17176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wallach D., Davies P. J., and Pastan I. (1978) Cyclic AMP-dependent phosphorylation of filamin in mammalian smooth muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 253, 4739–4745 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jay D., García E. J., and de la Luz Ibarra M. (2004) In situ determination of a PKA phosphorylation site in the C-terminal region of filamin. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 260, 49–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Woo M. S., Ohta Y., Rabinovitz I., Stossel T. P., and Blenis J. (2004) Ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) regulates phosphorylation of filamin A on an important regulatory site. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 3025–3035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li L., Lu Y., Stemmer P. M., and Chen F. (2015) Filamin A phosphorylation by Akt promotes cell migration in response to arsenic. Oncotarget 6, 12009–12019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Henkels K. M., Mallets E. R., Dennis P. B., and Gomez-Cambronero J. (2015) S6K is a morphogenic protein with a mechanism involving Filamin-A phosphorylation and phosphatidic acid binding. FASEB J. 29, 1299–1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang J., Neal J., Lian G., Shi B., Ferland R. J., and Sheen V. (2012) Brefeldin A-inhibited guanine exchange factor 2 regulates filamin A phosphorylation and neuronal migration. J Neurosci. 32, 12619–12629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang J., Neal J., Lian G., Hu J., Lu J., and Sheen V. (2013) Filamin A regulates neuronal migration through brefeldin A-inhibited guanine exchange factor 2-dependent Arf1 activation. J. Neurosci. 33, 15735–15746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ithychanda S. S., Fang X., Mohan M. L., Zhu L., Tirupula K. C., Naga Prasad S. V., Wang Y. X., Karnik S. S., and Qin J. (2015) A mechanism of global shape-dependent recognition and phosphorylation of filamin by protein kinase A. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 8527–8538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lad Y., Kiema T., Jiang P., Pentikäinen O. T., Coles C. H., Campbell I. D., Calderwood D. A., and Ylänne J. (2007) Structure of three tandem filamin domains reveals auto-inhibition of ligand binding. EMBO J. 26, 3993–4004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tirupula K. C., Ithychanda S. S., Mohan M. L., Naga Prasad S. V., Qin J., and Karnik S. S. (2015) G protein-coupled receptors directly bind filamin A with high affinity and promote filamin phosphorylation. Biochemistry 54, 6673–6683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Scott M. G., Pierotti V., Storez H., Lindberg E., Thuret A., Muntaner O., Labbé-Jullié C., Pitcher J. A., and Marullo S. (2006) Cooperative regulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation and cell shape change by filamin A and β-arrestins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 3432–3445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Onoprishvili I., Andria M. L., Kramer H. K., Ancevska-Taneva N., Hiller J. M., and Simon E. J. (2003) Interaction between the mu opioid receptor and filamin A is involved in receptor regulation and trafficking. Mol Pharmacol. 64, 1092–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li M., Bermak J. C., Wang Z. W., and Zhou Q. Y. (2000) Modulation of dopamine D(2) receptor signaling by actin-binding protein (ABP-280). Mol. Pharmacol. 57, 446–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Robertson S. P. (2005) Filamin A: phenotypic diversity. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 15, 301–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bertola D., Passos-Bueno M. R., Pereira A., Kim C., Morgan T., and Robertson S. P. (2015) Recurrence of frontometaphyseal dysplasia in two sisters with a mutation in FLNA and an atypical paternal phenotype: Insights into genotype-phenotype correlation. Am J Med Genet A. 167A, 1161–1164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van Kogelenberg M., Clark A. R., Jenkins Z., Morgan T., Anandan A., Sawyer G. M., Edwards M., Dudding T., Homfray T., Castle B., Tolmie J., Stewart F., Kivuva E., Pilz D. T., Gabbett M., Sutherland-Smith A. J., and Robertson S. P. (2015) Diverse phenotypic consequences of mutations affecting the C terminus of FLNA. J. Mol. Med. 93, 773–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Robertson S. P., Twigg S. R., Sutherland-Smith A. J., Biancalana V., Gorlin R. J., Horn D., Kenwrick S. J., Kim C. A., Morava E., Newbury-Ecob R., Orstavik K. H., Quarrell O. W., Schwartz C. E., Shears D. J., et al. (2003) Localized mutations in the gene encoding the cytoskeletal protein filamin A cause diverse malformations in humans. Nat. Genet. 33, 487–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sawyer G. M., Clark A. R., Robertson S. P., and Sutherland-Smith A. J. (2009) Disease-associated substitutions in the filamin B actin binding domain confer enhanced actin binding affinity in the absence of major structural disturbance: Insights from the crystal structures of filamin B actin binding domains. J. Mol. Biol. 390, 1030–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Clark A. R., Sawyer G. M., Robertson S. P., and Sutherland-Smith A. J. (2009) Skeletal dysplasias due to filamin A mutations result from a gain-of-function mechanism distinct from allelic neurological disorders. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 4791–4800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zenker M., Rauch A., Winterpacht A., Tagariello A., Kraus C., Rupprecht T., Sticht H., and Reis A. (2004) A dual phenotype of periventricular nodular heterotopia and frontometaphyseal dysplasia in one patient caused by a single FLNA mutation leading to two functionally different aberrant transcripts. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 74, 731–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Robertson S. P., Jenkins Z. A., Morgan T., Adès L., Aftimos S., Boute O., Fiskerstrand T., Garcia-Miñaur S., Grix A., Green A., Der Kaloustian V., Lewkonia R., McInnes B., van Haelst M. M., et al. (2006) Frontometaphyseal dysplasia: mutations in FLNA and phenotypic diversity. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 140, 1726–1736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Nakamura F., Heikkinen O., Pentikäinen O. T., Osborn T. M., Kasza K. E., Weitz D. A., Kupiainen O., Permi P., Kilpeläinen I., Ylänne J., Hartwig J. H., and Stossel T. P. (2009) Molecular basis of filamin A-FilGAP interaction and its impairment in congenital disorders associated with filamin A mutations. PLoS ONE 4, e4928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eftink M. R. (1994) The use of fluorescence methods to monitor unfolding transitions in proteins. Biophys. J. 66, 482–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Royer C. A. (2006) Probing protein folding and conformational transitions with fluorescence. Chem. Rev. 106, 1769–1784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ghisaidoobe A. B., and Chung S. J. (2014) Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence in the detection and analysis of proteins: a focus on Förster resonance energy transfer techniques. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 15, 22518–22538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim K. H., Yun S., Mok K. H., and Lee E. K. (2016) Thermodynamic analysis of ANS binding to partially unfolded α-lactalbumin: correlation of endothermic to exothermic changeover with formation of authentic molten globules. J. Mol. Recognit. 29, 446–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hawe A., Sutter M., and Jiskoot W. (2008) Extrinsic fluorescent dyes as tools for protein characterization. Pharm. Res. 25, 1487–1499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Seppälä J., Tossavainen H., Rodic N., Permi P., Pentikäinen U., and Ylänne J. (2015) flexible structure of peptide-bound filamin A mechanosensor domain pair 20–21. PLoS ONE 10, e0136969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Travis M. A., van der Flier A., Kammerer R. A., Mould A. P., Sonnenberg A., and Humphries M. J. (2004) Interaction of filamin A with the integrin β 7 cytoplasmic domain: role of alternative splicing and phosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 569, 185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ithychanda S. S., and Qin J. (2011) Evidence for multisite ligand binding and stretching of filamin by integrin and migfilin. Biochemistry 50, 4229–4231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mezawa M., Pinto V. I., Kazembe M. P., Lee W. S., and McCulloch C. A. (2016) Filamin A regulates the organization and remodeling of the pericellular collagen matrix. FASEB. J. 30, 3613–3627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., and Bax A. (1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.