Abstract

Background

In a survey taken in Germany in 2015, 14.1% of the 12– to 17-year-olds surveyed had practiced binge drinking at least once in the preceding 30 days. The school program “Klar bleiben” (“Keep a Clear Head”) was designed for and implemented among 10th graders. The participants committed themselves to abstain from binge drinking for 9 weeks. We studied whether this intervention influenced the frequency and intensity of binge drinking.

Methods

This cluster-randomized controlled trial was carried out in 196 classes of 61 schools, with a total of 4163 participants with a mean age of 15.6 years (standard deviation 0.73 years). Data were collected by questionnaire in late 2015, before the intervention and again six months later. The primary endpoints were the frequency of consumption of at least 4 or 5 alcoholic drinks (for girls and boys, respectively) and the typical quantity consumed. This trial was registered in the German Clinical Trials Registry (Deutsches Register Klinischer Studien, DRKS) with the DRKS ID number DRKS00009424.

Results

At the beginning of the trial, there was no difference between the intervention group and the control group with respect to the primary endpoints. After the intervention, differences were found among participants who had consumed alcohol before the trial (73.2% of the overall sample): binge drinking at least once in the preceding month was reported by 49.4% of the control group and by 44.2% in the intervention group (p = 0.028). The mean number of alcoholic drinks consumed in each drinking episode was 5.20 in the control group and 5.01 in the intervention group (p = 0.047).

Conclusion

The intervention was effective only in the large subgroup of adolescents who had previously consumed alcohol: they drank alcohol less often and in smaller amounts than their counterparts in the control group.

Alcohol consumption is widespread among the German population. In recent years it has remained at a constantly high level of almost 10 L of pure alcohol per person per year (1). Calculations based on epidemiological models put the number of 18– to 64-year-olds who have consumed alcohol within the last 30 days at approximately 37 million (2). Almost 12 million people in this age group also engage in occasional binge drinking, defined as consumption of 5 or more alcoholic drinks on one day in the last 30 days. According to the World Health Organization’s Global status report on alcohol and health, this makes Germany a high-alcohol-consumption country (3). High consumption figures are relevant medically and for health policy, because in 2015 alcohol consumption was one of the 10 main factors responsible for reduced quality of life and premature death worldwide (4).

Alcohol remains by far the most popular drug among adolescents. Although occasional weekly alcohol consumption among adolescents is falling slightly (5, 6), consumption is widespread among adolescents in Germany and is ranked as high in international comparisons (7). Germany’s Federal Centre for Health Education (Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung, BZgA) estimates that in 2015 almost 70% of 12– to 17-year-olds in Germany had already drunk alcohol, and that approximately 1 in 7 adolescents had consumed 4 or more alcoholic drinks on at least one of the last 30 days (6).

Alcohol consumption reduces coordination and the ability to react and at the same time increases the readiness to take risks. Alcohol consumption among adolescents can have direct adverse consequences, including vandalism, violence, sexual assault, suicide, and accidents (8). Furthermore, brain development is not yet complete during adolescence, so frequent alcohol consumption in particular can lead to an accelerated decrease in volume in the frontal and temporal cortical structures—important for behavior control and memory— and reduced growth of white matter (9). In addition, there is mounting evidence that adolescents who frequently consume large quantities of alcohol maintain this consumption pattern in adulthood, rather than giving it up. This leads to the associated danger of subsequent alcohol-related problems (10).

Various behavioral preventive measures have been developed in Germany to prevent binge drinking in adolescents. Examination of 208 alcohol prevention projects revealed that only 11 of the prevention programs were suitable for investigation of their efficacy. Two of these studies were rated as having adequate methodologies (11): one controlled trial on the elementary-school program Klasse2000 (“Class 2000”) showed that at follow-up 36 months after the end of grade 4 of elementary school (age 10, thus age 13 at follow-up) alcohol consumption was lower in the intervention group than in the control group among adolescents who had already consumed alcohol (12). The findings of a cluster-randomized study on the alcohol prevention program Aktion Glasklar (“Action Crystal Clear”), aimed at students in their first year of secondary school (age 10 to 12) a significant preventive effect on binge drinking in adolescents one year after the end of the intervention (13).

This study aims to investigate the efficacy of a new school-based approach to preventing binge drinking in adolescents. This initiative is applied to class groups and aims to establish a social norm of not binge drinking.

Methods

Intervention

The school-based prevention program Klar bleiben (“Stay clear-headed”) aims to reduce binge drinking and to develop a responsible attitude to alcohol. It is aimed at grade 10 classes (age 15 to 16) and is implemented by teachers. Students in the participating classes undertake to refrain from binge drinking for 9 weeks. This undertaking is put in writing by all the students signing a class contract (contract management). Every 2 weeks, the drinking behavior of the students is recorded as a class. The aim is for at least 90% of the class not to engage in binge drinking. Classes that remain “binge-free” throughout then enter a raffle to win prizes. The intervention also includes four ideas for class activities on the subject of alcohol (ebox 1).

eBOX 1. Description of intervention materials.

The school-based prevention program Klar bleiben was developed as part of Germany’s nationwide alcohol prevention campaign for adolescents, Alkohol? Kenn dein Limit (“Alcohol? Know your limit,” www.kenn-dein-limit.info). This was instigated by the Federal Centre for Health Education (BZgA, Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung). To implement the program, the classes and their teachers received a package containing the following items:

Class contract on refraining from binge drinking

Poster to document feedback on how well this undertaking had been complied with

Teacher’s brochure with instructions on implementing the intervention

Cards for postal feedback

Instructions for copying the student contract in order to make the undertaking individual

-

Four ideas for class activities to explore the subject more deeply:

Social norms

Reasons for drinking

Expected effects of alcohol and consequences of consuming it

Advertising of alcohol

Materials for the BZgA’s Kenn dein Limit initiative: informational DVD, order list for additional materials

Informational leaflet on the intervention for parents

Additional information and materials can be found online at www.klar-bleiben.de.

Design

This study is a cluster-randomized, two-arm controlled trial (14). Students in the intervention group took part in the ‘Klar bleiben’-program from January to March 2016. During the same period, those in the control group pursued the normal school curriculum instead of undergoing any specific intervention. Both groups completed a preintervention questionnaire in November and December 2015 and a postintervention questionnaire between April and July 2016, concerning their alcohol consumption. Randomization was performed at the school level to rule out interference between the intervention and control groups (ebox 2).

eBOX 2. Randomization.

Randomization was performed using the software program Randomization In Treatment Arms (RITA) (21). It was stratified in order to ensure a balanced ratio between the two study arms of the following influencing factors: state, school type, school size (based on the number of grade 10 classes in each school).

The study was approved by the relevant education authorities of the states of Schleswig-Holstein and Lower Saxony and was rated as ethically sound by the ethics committee of the German Psychological Society (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychologie, DGPs). The students’ parents were informed of the study in writing and had the opportunity to oppose their children’s participation in it.

Participants and procedure

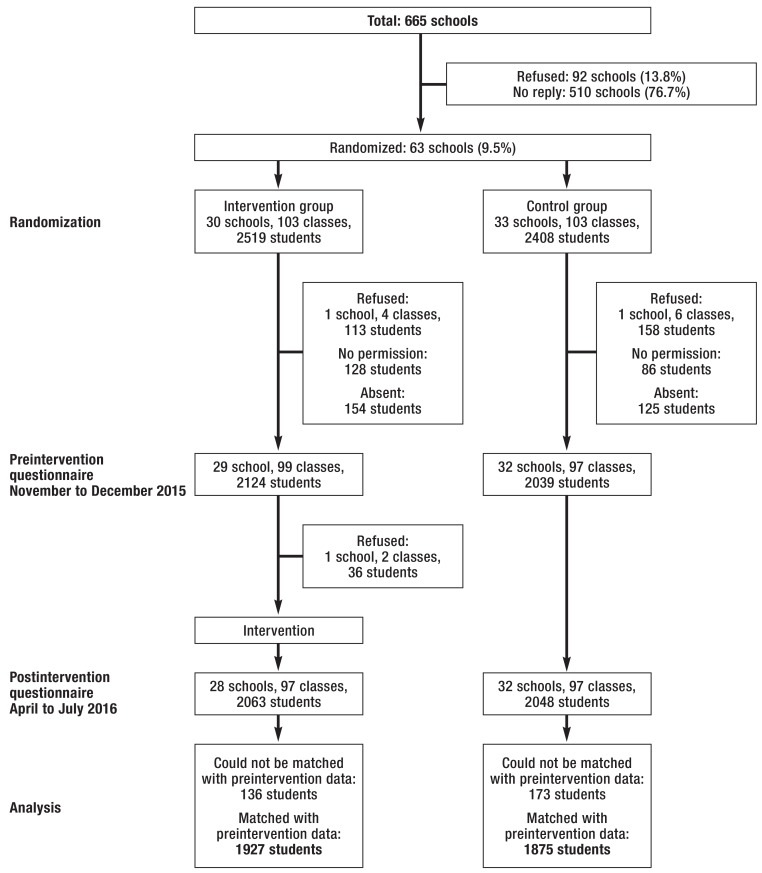

A priori power analysis showed a required sample size of at least 3000 students and 150 classes (ebox 3). A flow diagram illustrates enrolment, randomization, follow-up, and data analysis of the sample (figure 1). Additional information is provided in eBox 4.

eBOX 3. Power analysis.

In this study, the clusters into which students were divided for evaluation were their classes. Power analysis was performed at the individual (student) level, and the cluster effect was examined using intraclass correlation (ICC). With an anticipated level of risk-entailing consumption approximately 20% lower in the intervention group than in the control group, an a value of 5% and a statistical power of 0.80 yields a required sample size of 1950 individuals (975 per group). With an ICC of 0.015— the prevalence of experience of drunkenness in the last 30 days found in the European Drug Abuse Prevention Trial, the largest European study on school-based prevention (22)—and approximately 20 students per class, i.e. per cluster, the required sample size increases as follows (23, 24): (1 + (20 – 1) × 0.015) × 1950 = 2506.

Finally, on the basis of earlier studies in school settings, a dropout rate of approximately 15% of students was assumed. This meant that the total sample size needed was at least 3000 students from 150 classes.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study

eBOX 4. Procedure.

In the fall of 2015, total of 665 standard-curriculum schools in the German federal states of Schleswig-Holstein and Lower Saxony were invited in writing to take part in the study. Sixty-three schools (9.5%) said they were prepared to do so. Thirty schools were randomized to the intervention group and 33 to the control group. All data was recorded for individual students. One school left each arm of the study before any data was recorded. Baseline data was recorded for a total of 4163 students. One additional school, with 2 classes, left the intervention group during the course of the study. Because all students for whom permission had been given completed the questionnaires on the days set for data recording in each particular school, it is possible that in some classes more students completed postintervention questionnaires than preintervention questionnaires, due to differing rates of absence. Datasets for 3802 students were matched with each other for the 2 days on which data was recorded. This corresponds to a retention rate of 91.3%. There was a mean of 169 days between the days on which data was recorded (range: 110 to 249 days). A mean of 63 days (range: 24 to 122 days) elapsed between the end of the intervention and the postintervention questionnaire.

The questionnaires were administered by trained IFT-Nord staff to ensure that data was recorded completely anonymously. Neither those recording the data nor the students were blinded. Seven-character codes were used so that the preintervention and postintervention questionnaires could be matched. The codes were generated by the students themselves. This procedure had already been used in previous school-based longitudinal studies (25). These codes cannot be used to trace students’ identities.

Questionnaire

Primary outcomes: The primary outcomes of the study were frequency, intensity, and consequences of binge drinking. To define binge drinking, the 5+/4+ measure has been established in the international literature (15). This uses the following questions to ascertain whether adolescents have ever engaged in binge drinking: “Have you ever had 4 or more (girls)/5 or more (boys) drinks of alcohol on one occasion?” (Yes/No). The following question determines the frequency of binge drinking: “How often do you drink 4 or more (girls)/5 or more (boys) drinks of alcohol on one occasion?” Possible answers are as follows: “Never,” “Less than monthly,” “Monthly,” “Weekly,” “Daily or almost daily.” The answers were converted into a binary outcome for statistical analysis: “Monthly” or more frequently versus other answers.

The question “When you drink alcohol, how many drinks of alcohol do you typically drink on one day?” is used to determine the intensity of binge drinking. The following prompt is provided: “One drink of alcohol is approximately 0.3 L beer, 0.1 L of wine/champagne, or 0.04 L (2 glasses) spirits.” The possible answers are numbers from “1” to “10 or more.”

The CRAFFT-d (Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble) Screening Test was used to ascertain any associated alcohol-related problems (16) (ebox 5).

eBOX 5. The CRAFFT-d Screening Test.

Have you ever ridden in a CAR driven by someone (including yourself) who had been using alcohol?

Do you ever use alcohol to RELAX, feel better about yourself, or fit in?

Do you ever use alcohol while you are by yourself, or ALONE?

Do you ever FORGET things you did while using alcohol?

Do your FAMILY or FRIENDS ever tell you that you should cut down on your drinking?

Have you ever gotten into TROUBLE while you were using alcohol?

Possible answers: Yes/No

Cronbach’s alpha: 0.56

Range: 0 to 6

CRAFFT: Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble

Secondary outcomes: Secondary outcomes included general alcohol use (lifetime prevalence, current consumption), social factors (susceptibility, perceived descriptive norm), alcohol-related cognition (reasons for drinking, self-efficacy regarding alcohol, expected effects of alcohol), and use of other substances (cigarettes, cannabis/marijuana) (ebox 6).

eBOX 6. Secondary outcomes.

Whether students had already consumed alcohol was determined using the question “Have you ever drunk alcohol?” Possible answers were as follows: “Yes,” “Yes, but only a couple of sips,” “No.” The frequency of alcohol consumption was ascertained using the question “How often do you currently drink alcohol?” and the possible answers “Neverl,” “Less than monthly,” “Monthly,” “2 to 3 times a month,” “Weekly,” “2 to 4 times a week,” and “Daily or almost daily”

Turning to social factors, susceptibility to alcohol consumption was determined in line with the procedure of Pierce et al. (questions “Do you think you will drink alcohol 1 year from now?” and “If one of your best friends were to offer you alcohol, would you drink it?”, possible answers “Definitely yes,” “Probably yes,” “Probably not,” and “Definitely not” [26]). Those who had never consumed alcohol and had answered “Definitely not” to both questions were classified as not susceptible. In addition, an 11-point scale ranging from 0 = none to 10 = all was used to ascertain how widespread students believed alcohol consumption to be among adolescents of their age.

Reasons for drinking were recorded using the motives stated in the Drinking Motives Questionnaire Revised Short Form (27): a total of 12 questions determine the frequency of alcohol consumption for social motives (e.g. “Because it helps you enjoy a party.”), enhancement motives (e.g. “Because it’s fun.”), coping motives (e.g. “To forget about your problems.”), and social pressure and conformity motives (e.g. “So you won’t feel left out.”). The frequency of alcohol consumption for each reason is classified as “(Almost) never,” “Some of the time,” “Half of the time,” “Most of the time,” “(Almost) always”. Each scale ranges from 3 to 15. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.88 for social motives, 0.85 for enhancement motives, 0.90 for coping motives, and 0.80 for social pressure and conformity motives.

Self-efficacy regarding alcohol was recorded using the Drinking Refusal Self-Efficacy Questionnaire—Revised Adolescent Version (28). This requires the probability of being able to resist drinking to be rated for a total of 19 situations (e.g. “When I am at a party,” “When I feel sad”) on a scale ranging from 1 = absolutely unsure to 6 = absolutely sure. The total score ranges from 19 to 114, and Cronbach’s alpha was 0.95.

As additional cognitive variables, expected effects of alcohol were recorded using the abbreviated German-language version of the Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire (29). To complete this, one must decide whether 19 possible effects of alcohol (e.g. “After a few drinks I am usually in a better mood,” “Alcohol makes me feel less shy.”) do or do not apply (possible answers: agree/disagree). This gives a total score of between 0 and 19. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91.

Use of other substances was ascertained using the frequency of current cigarette and cannabis use. The possible answers were “Never,” “Less than monthly,” “At least monthly, but not weekly,” “At least weekly, but not daily,” and “Daily.”

Social demographics and covariates: Age, sex, religion, and type of school were documented. The language mostly spoken at home was recorded as an indicator of a migrant background. Parents’ level of education was recorded as an indicator of socioeconomic status. Alcohol consumption in students’ environment, in terms of friends, was recorded using the question “How many of your friends drink alcohol?” Possible answers were “None,” “Not many,” “Some,” “Most,” and “All.” This variable was converted into binary form for statistical analysis: “Most” and “All” versus other answers. The personality traits sensation-seeking and impulsiveness were determined using the Substance Use Risk Profile Scale (17) (ebox 7).

eBOX 7. Substance Use Risk Profile Scale (sensation-seeking and impulsiveness).

1. I often don’t think things through before I speak.

2. I would like to skydive.

3. I often involve myself in situations that I later regret being involved in.

4. I enjoy new and exciting experiences even if they are unconventional.

5. I like doing things that frighten me a little.

6. I usually act without stopping to think.

7. I would like to learn how to drive a motorcycle.

8. Generally, I am an impulsive person.

9. I am interested in experience for its own sake even if it is illegal.

10. I would enjoy hiking long distances in wild and uninhabited territory.

11. I feel I have to be manipulative to get what I want.

Possible answers for all items: Strongly disagree/Disagree/Agree/Strongly agree.

Cronbach’s alpha: 0.69

Range: 1 to 4

Statistical analyses

The effects of the intervention were tested using multilevel logistic and linear regression at the class and individual levels. In addition to group and time variables and the interaction term group × time, all variables which differed substantially between the study groups at baseline were recorded as covariates (school type, religion, parents’ level of education, peers’ alcohol consumption). Analyses were performed both for the sample as a whole and for only those who had reported prior alcohol consumption in the preintervention questionnaire (73.2% of the total sample) (ebox 8).

eBOX 8. Statistical analyses.

Depending on the answer format for the variables in question, t-tests for independent samples and chi-square tests were used to test for differences between the characteristics of the 2 groups in the preintervention questionnaire,. For attrition analysis, logistic regression was used to predict the study dropout rate; an interaction term, variable × group condition, was introduced to test for potential selective dropouts. Multilevel logistic or linear regression at the class and individual levels were used to test for intervention effects. In addition to group and time variables and the interaction term group × time, all variables which showed substantial differences between the study groups at baseline (school type, religion, parents’ level of education, peers’ alcohol consumption) were recorded as covariates. Adjusted frequencies and means were calculated for the primary outcomes on the basis of this model. Analyses were performed both for the sample as a whole and for only students who had reported prior alcohol consumption in the preintervention questionnaire (73.2% of the total sample). Absolute and relative risk reductions were calculated as indicators of effect size. All tests were 2-tailed, and probabilities of error of a <0.05 were taken to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA 14.2.

Results

Attrition analysis

361 students (8.7%) did not complete the study. The levels of attrition in the intervention and control groups were similar (ebox 9).

eBOX 9. Attrition analysis.

In both groups, dropout rates were higher among male participants, at older ages, among students with a migrant background, and among those who had no religion or were Muslims. Students who dropped out had higher scores for sensation-seeking and impulsiveness, reported more frequent binge drinking at baseline and more drinks per occasion, and scored higher on CRAFFT-d. However, for these variables there was no evidence of selective dropouts, i.e. there was no difference between the dropout patterns in the 2 study arms.

CRAFFT: Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble

Description of sample

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample at baseline. Compared to the intervention group, the control group contained more university preparatory high school students and fewer students from other types of schools. In addition, the level of education of the students’ parents was higher, more students had no religious affiliation, and more students reported that their friends consumed alcohol more frequently. There were no differences between the groups in terms of whether they had ever consumed alcohol or the frequency or intensity of binge drinking. Students in the control group scored significantly higher on the CRAFFT-d test.

eTable 1. Correlation between the severity of sensation-seeking/impulsiveness and frequency/intensity of binge drinking.

| Frequency of at least monthly binge drinking | No. of drinks consumed per occasion | |||

| Preintervention questionnaire | Postintervention questionnaire | Preintervention questionnaire | Postintervention questionnaire | |

| % | % | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Sensation-seeking and impulsiveness | ||||

| Low/below median | 22.5% | 28.6% | 3.76 (2.50) | 4.20 (2.61) |

| High/above median | 38.0 % | 44.6% | 4.89 (2.86) | 5.28 (2.78) |

| Χ² (df); p | Χ² (df); p | t (df); p | t (df); p | |

| Test for difference between groups | 107.8 (1) <0.001 |

103.6 (1) <0.001 |

11.3 (2 862) <0.001 |

11.4 (3 164) <0.001 |

df: Degrees of freedom; M: Mean; p: Observed significance level; SD: Standard deviation

Frequency and intensity of binge drinking were strongly associated with the personality traits sensation-seeking and impulsiveness (etable 1).

Effects of the intervention

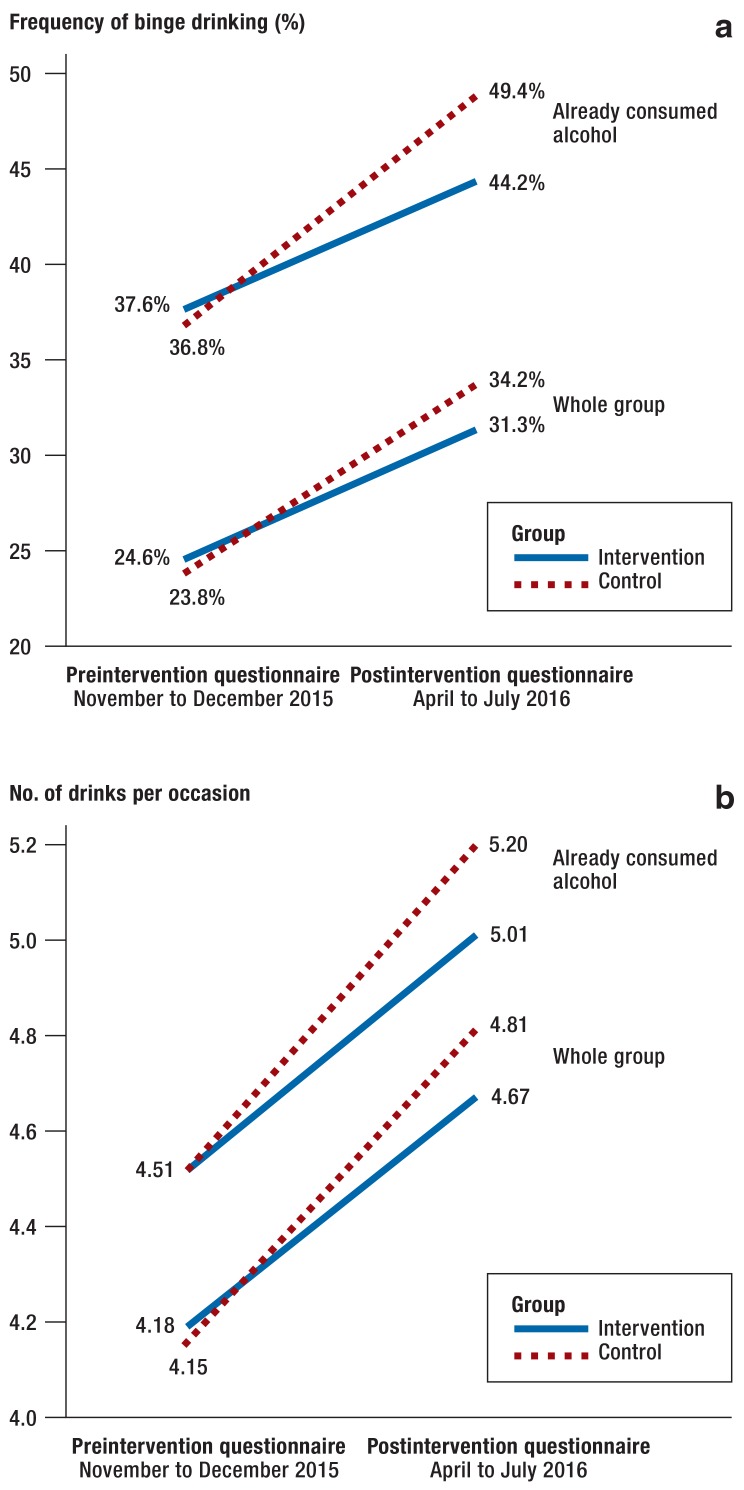

Primary outcomes: For the sample as a whole, the rate of binge drinking at least once a month according to the postintervention questionnaire was 2.9 percentage points lower in the intervention group than in the control group (figure 2). This difference was not statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Intensity of binge drinking

a) Frequency of binge drinking, defined as at least monthly consumption of 4 or more (girls) or 5 or more (boys) drinks of alcohol on one occasion, in the groups over time. Adjusted relative frequencies are shown (covariates: school type, socioeconomic status, religion, friends’ consumption, class as cluster).

b) Mean number of drinks per occasion in the groups over time. Adjusted means are shown (covariates: school type, socioeconomic status, religion, friends’ consumption, class as cluster).

For adolescents who had already consumed alcohol, the difference in frequency of binge drinking and thus absolute risk reduction after the intervention was 5.2% percentage points. This is equivalent to a relative risk reduction of 10.4% in comparison to the control group. The adjusted odds ratio for the interaction term group × time is significant, at 1.38 (Table 2).

eTable 2. Secondary outcomes in preintervention and postintervention questionnaires and tests for intervention effects.

| Preintervention questionnaire | Postintervention questionnaire | Interaction | |||||

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Group × time | |||

| Variable [range]* | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | Adj. b | 95% CI | p |

| Current frequency of consumption [0 to 6] | 1.57 (1.35) | 1.67 (1.40) | 1.81 (1.38) | 1.90 (1.43) | – 0.01 | [−0.09; 0.07] | 0.809 |

| Social norm [0 to 10] | 7.33 (1.51) | 7.39 (1.53) | 7.01 (1.70) | 7.16 (1.62) | 0.10 | [−0.03; 0.22] | 0.116 |

| Self-efficacy regarding alcohol [19 to 114] | 96.86 (18.29) | 97.25 (16.90) | 98.63 (17.03) | 98.50 (16.22) | – 0.53 | [−1.69; 0.63] | 0.367 |

| Expected effects [0 to 19] | 7.54 (5.47) | 8.00 (5.49) | 7.26 (5.46) | 7.71 (5.55) | – 0.03 | [−0.30; 0.25] | 0.848 |

| Current frequency of cigarette use [0 to 4] | 0.46 (1.08) | 0.50 (1.12) | 0.55 (1.18) | 0.58 (1.19) | – 0.00 | [−0.06; 0.05] | 0.844 |

| Current frequency of cannabis use [0 to 4] | 0.18 (0.61) | 0.23 (0.70) | 0.22 (0.68) | 0.29 (0.77) | 0.02 | [−0.02; 0.06] | 0.273 |

| Those who had never consumed alcohol only | Prozent | % | % | % | Adj. OR | 95% CI | p |

| Increase in lifetime prevalence | – | – | 3.0 % | 2.5 % | 0.94 | [0.61; 1.44] | 0.773 |

| Susceptibility | 22.1 % | 21.6 % | 16.6 % | 18.1 % | 0.96 | [0.17; 5.17] | 0.964 |

| Those who had consumed alcohol only | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | Adj. b | 95% CI | p |

| Current frequency of consumption [0 to 6] | 2.08 (1.21) | 2.20 (1.23) | 2.26 (1.24) | 2.38 (1.27) | – 0.02 | [−0.11; 0.08] | 0.711 |

| Social norm [0 to 10] | 7.45 (1.43) | 7.50 (1.50) | 7.06 (1.68) | 7.21 (1.63) | 0.11 | [−0.04; 0.26] | 0.137 |

| Self-efficacy regarding alcohol [19 to 114] | 93.89 (16.52) | 94.22 (15.34) | 96.60 (14.74) | 95.86 (14.56) | – 1.08 | [−2.28; 0.13] | 0.079 |

| Expected effects [0 to 19] | 8.99 (4.85) | 9.58 (4.75) | 8.79 (4.93) | 9.42 (4.86) | – 0.01 | [−0.30; 0.29] | 0.971 |

| Social motives [3 to 15] | 8.45 (3.61) | 9.05 (3.68) | 7.76 (3.52) | 8.53 (3.59) | 0.18 | [−0.05; 0.41] | 0.122 |

| Enhancement motives [3 to 15] | 7.54 (3.40) | 7.97 (3.58) | 7.11 (3.41) | 7.73 (3.52) | 0.19 | [−0.03; 0.40] | 0.084 |

| Coping motives [3 to 15] | 4.99 (2.84) | 5.15 (2.96) | 4.65 (2.46) | 4.83 (2.61) | 0.01 | [−0.17; 0.20] | 0.876 |

| Social pressure and conformity motives [3 to 15] | 3.73 (1.62) | 3.77 (1.64) | 3.42 (1.34) | 3.45 (1.31) | – 0.01 | [−0.13; 0.12] | 0.922 |

| Current frequency of cigarette use [0 to 4] | 0.60 (1.21) | 0.68 (1.25) | 0.71 (1.29) | 0.78 (1.33) | 0.00 | [−0.06; 0.07] | 0.909 |

| Current frequency of cannabis use [0 to 4] | 0.24 (0.69) | 0.30 (0.80) | 0.30 (0.78) | 0.38 (0.87) | 0.02 | [−0.03; 0.08] | 0.355 |

Adj. b: Adjusted regression coefficient b; Adjusted OR: Adjusted odds ratio; M: Mean; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval; p: Observed significance level; SD: Standard deviation

*In the first section the range of each variable is shown in brackets. School type, socioeconomic status, religion, and friends’ consumption were controlled for in all analyses.

Figure 2 also shows the findings concerning intensity of binge drinking. For the sample as a whole, the absolute mean difference between the groups after the intervention, 0.14 alcoholic drinks per occasion, is insignificant (Table 2). Adolescents in the intervention group who had already consumed alcohol consumed significantly less on one occasion—0.19 fewer alcoholic drinks—than those in the control group (adjusted regression coefficient for the interaction term group × time: 0.19) (Table 2).

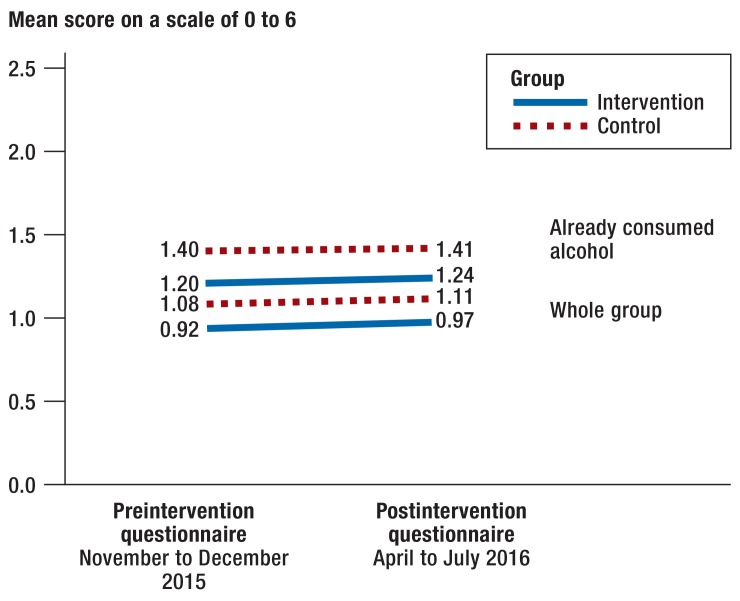

The intervention had no significant effects regarding consequences of alcohol consumption (eFigure, Table 2).

eFigure.

Alcohol-related problems in the groups over time, recorded using CRAFFT-d

Adjusted means are shown (covariates: school type, socioeconomic status, religion, friends’ consumption, class as cluster).

CRAFFT: Car. Relax. Alone. Forget. Friends. Trouble

Secondary outcomes: The intervention had no significant effects regarding general alcohol use, social factors, alcohol-related cognition, or use of other substances (etable 2).

Discussion

The findings of this cluster-randomized study show that school-based intervention programs can have an effect on the frequency and intensity of binge drinking among adolescents who have already consumed alcohol. A 2011 Cochrane review on the efficacy of school-based alcohol prevention programs included 53 studies, most of which were cluster-randomized (18). Quantitative meta-analysis could not be performed, due to the great variation between interventions, study groups, and outcome measures. Six of the 11 studies that investigated alcohol-specific interventions found a preventive effect when compared to the standard curriculum. There were preventive effects either for the whole population or for certain subgroups in 14 of the 39 studies testing interventions that aimed to prevent several risk-entailing behaviors simultaneously (e.g. alcohol, tobacco, or drug use, antisocial behavior). The findings of the 3 remaining studies, which investigated interventions targeting misuse of alcohol and cannabis, drugs and alcohol, and tobacco alone, were inconsistent.

One cluster-randomized study involving a cohort of grade 7 German students (age 12 to 13) showed that school-based programs targeting younger students below the legal minimum age for purchasing alcohol could at least delay the beginning of binge drinking (13).

Our research shows that school-based, alcohol-specific interventions can also reduce the frequency and intensity of binge drinking among grade 10 students who report that they have already consumed alcohol and can purchase it legally. No effects of the intervention on associated alcohol-related problems were observed. Such problems were documented using CRAFFT-d. The very low mean values suggest a floor effect. In addition, the internal consistency of the scale was not satisfactory.

During the half-year observation period it became clear that the frequency and intensity of binge drinking and associated alcohol-related problems were increasing in both study groups. The explanation for this is that on completing the postintervention questionnaire, unlike at baseline, the students were on average 16 years old and could therefore legally purchase beer, wine, and champagne. In the very large subgroup of adolescents who had already consumed alcohol before the study, the intervention had a small preventive effect on both the frequency and the intensity of binge drinking.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that must be taken into account when interpreting its findings. Despite randomization, which took the form of cluster-randomization, the preintervention questionnaire revealed differences between the study groups in terms of some variables, although not in terms of the outcome measures. Statistical analysis therefore controlled for the substantial baseline differences between the groups. Attrition of participants over time must also be taken into account: 8.7% of the participating students could not be contacted again for the postintervention questionnaire. However, a bias in the study findings is unlikely, as there was no selective attrition. In addition, the data obtained is subjective information documented using questionnaires, rather than objective measurements. Systematic tendencies in the answers given in these questionnaires are perfectly possible. For example, there may have been a tendency to give socially desirable answers, particularly in the intervention group.

There is also the question of whether the findings of this study can be extrapolated to other settings. The study was conducted in two federal states in the west of Germany, so it is at least possible that there are regional differences between these and other German federal states. For instance, it is known that more beer but less wine and spirits are drunk in southern federal German states than in northern ones (19). Finally, follow-up was possible on only one occasion, in a postintervention questionnaire a mean of 9 weeks after the end of the intervention. This means that conclusions can only be drawn on the immediate effects of the intervention program, not on its medium- or even long-term effects. The analyses presented here did not control for how well the intervention was implemented, i.e. classes in which it was implemented very thoroughly have been included in the evaluation in the same way as classes in which it was not implemented according to instructions or in which it was not completed. We have thus taken a conservative approach. Unpublished subgroup analyses indicate that the effects of the intervention were greater when it was implemented successfully and comprehensively than in classes in which implementation was rudimentary or the intervention was not implemented at all.

Summary

The findings presented here are encouraging, as is the fact that the intervention was relatively inexpensive. The core of the intervention, students entering into a contract to refrain from binge drinking, has become an established method in the primary prevention of smoking (20) but to the best of our knowledge had not previously been used in the prevention of alcohol consumption. These findings must be replicated elsewhere, and sufficiently long follow-up must be performed.

Table 1. Baseline sample characteristics (November to December 2015).

| Intervention group (n = 2124) | Control group (n = 2039) | p-value | |

| Percentage/mean (SD) | Percentage/mean (SD) | ||

| Sex | 0.834 | ||

| – Female | 51.9% | 52.2% | |

| – Male | 48.1% | 47.8% | |

| Age | 15.62 (0.73) | 15.60 (0.73) | 0.236 |

| School type | <0.001 | ||

| – University preparatory high school | 41.7% | 48.8% | |

| – Other | 58.3% | 51.2% | |

| Migrant background | 0.897 | ||

| – Main language not German | 8.9% | 8.8% | |

| Religion | <0.001 | ||

| – Christianity | 69.9% | 66.2% | |

| – Islam | 8.4% | 7.1% | |

| – Other | 1.4% | 1.2% | |

| – None | 20.3% | 25.6% | |

| Parents’ level of education | <0.001 | ||

| – Secondary school certification allowing entrance to a university: both parents |

12.9% | 20.4% | |

| – Secondary school certification allowing entrance to a university: one parent |

22.6% | 23.4% | |

| – Secondary school certification allowing entrance to a university: neither parent |

64.6% | 56.2% | |

| Sensation-seeking and impulsiveness | 2.36 (0.46) | 2.37 (0.46) | 0.660 |

| Alcohol consumption in environment | 0.004 | ||

| – Most or all friends drink | 49.9% | 54.5% | |

| Ever drunk alcohol | 0.905 | ||

| – No | 10.8% | 10.3% | |

| – Only a few sips | 16.2% | 16.3% | |

| – Yes | 73.1% | 73.3% | |

| Usual quantity drunk (no. of drinks) | 4.32 (2.78) | 4.41 (2.75) | 0.370 |

| Ever engaged in binge drinking | 0.850 | ||

| – Yes | 58.3% | 58.0% | |

| – No | 41.7% | 42.0% | |

| Frequency of binge drinking | 0.332 | ||

| – Never | 39.4% | 39.8% | |

| – Less than once per month | 30.7% | 30.0% | |

| – Once per month | 23.0% | 21.7% | |

| – Once per week | 6.6% | 8.2% | |

| – Daily or almost daily | 0.3% | 0.3% | |

| Alcohol-related consequences (total CRAFFT-d score) | 0.95 (1.19) | 1.10 (1.29) | <0.001 |

CRAFFT: Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble (screening test); p: Observed significance level; SD: Standard deviation

Tablle 2. Inferential statistics on frequency of binge drinking, amount consumed, and associated consequences in groups over time.

| Total sample (n = 3802) | Those who had already consumed alcohol (n = 2779) | |||||

| Adj. OR | 95% CI | p | Adj. OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Frequency of at least monthly binge drinking | ||||||

| – Time effect | 1.59 | [1.30; 1.94] | <0.001 | 1.42 | [1.15; 1.74] | 0.001 |

| – Group effect | 0.95 | [0.69; 1.30] | 0.730 | 0.96 | [0.70; 1.30] | 0.783 |

| – Interaction effect: group × time | 1.30 | [0.97; 1.72] | 0.071 | 1.38 | [1.03; 1.85] | 0.028 |

| Adj. b | 95% CI | p | Adj. b | 95% CI | p | |

| No. of drinks consumed per occasion | ||||||

| – Time effect | 0.49 | [0.37; 0.62] | <0.001 | 0.50 | [0.37; 0.64] | <0.001 |

| – Group effect | – 0.03 | [– 0.29; 0.23] | 0.838 | 0.00 | [– 0.28; 0.27] | 0.988 |

| – Interaction effect: group × time | 0.17 | [– 0.01; 0.35] | 0.054 | 0.19 | [0.00; 0.38] | 0.047 |

| Total CRAFFT-d score | ||||||

| – Time effect | 0.05 | [0.00; 0.10] | 0.035 | 0.04 | [– 0.02; 0.10] | 0.193 |

| – Group effect | 0.16 | [0.07; 0.24] | <0.001 | 0.20 | [0.08; 0.31] | <0.001 |

| – Interaction effect: group × time | – 0.02 | [– 0.09; 0.05] | 0.635 | – 0.02 | [– 0.11; 0.07] | 0.569 |

Adj. b: Adjusted regression coefficient b; Adjusted OR: Adjusted odds ratio; CRAFFT: Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, Trouble (screening test); 95% CI: 95%

confidence interval; p: Observed significance level

School type, socioeconomic status, religion, and friends’ consumption were controlled for in all analyses.

Key Messages.

Of the investigated grade 10 students (age 15 to 16), 89% have consumed at least a few sips of alcohol at some point in their lives.

Binge drinking is common: 58% of a total of 4163 students have consumed 4 (girls) or 5 (boys) alcoholic drinks on one day at some point in their lives.

The prevention program Klar bleiben is applied to class groups and aims to use contract management to establish a social norm of not binge drinking.

With a relative risk reduction of 10.4%, the intervention program showed a preventive effect in terms of the frequency of at least monthly binge drinking among adolescents who had already consumed alcohol.

At the end of the intervention this group of adolescents consumed a mean of 0.19 fewer alcoholic drinks per occasion than comparable adolescents in the control group.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Toska Jakob, Corinna Köhler, Luise Rehermann, Milene Wiehl, Jörn Frischemeier, Markus Watermeyer, Hanife Özbek, Melanie Maida, Myriam Lemberger, Sarah C. Murray, and Lena Heister for their support in data collation. We would also like to thank all the schools, teachers, and students involved for their collaboration.

Funding

The study was sponsored by Germany’s Federal Centre for Health Education (BZgA, Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung) and commissioned by Germany’s Federal Ministry of Health.

IFT-Nord both developed and evaluated the intervention.

Translated from the original German by Caroline Shimakawa-Devitt, M.A.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Batra A, Muller CA, Mann K, Heinz A. Alcohol dependence and harmful use of alcohol. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:301–310. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Matos EG, Atzendorf J, Kraus L, Piontek D. Substanzkonsum in der Allgemeinbevölkerung in Deutschland. Sucht. 2016;62:271–281. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. World Health Organization. Geneva: Global status on alcohol and health—2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1659–1724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Looze M, Raaijmakers Q, Bogt TT, et al. Decreases in adolescent weekly alcohol use in Europe and North America: evidence from 28 countries from 2002 to 2010. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(2):69–72. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung. Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung. Köln: 2016. Die Drogenaffinität Jugendlicher in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 2015. Rauchen, Alkoholkonsum und Konsum illegaler Drogen: aktuelle Verbreitung und Trends. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braker AB, Soellner R. Alcohol drinking cultures of European adolescents. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26:581–586. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckw033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stolle M, Sack PM, Thomasius R. Binge drinking in childhood and adolescence: epidemiology, consequences, and interventions. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106:323–328. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Squeglia LM, Tapert SF, Sullivan EV, et al. Brain development in heavy-drinking adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:531–542. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14101249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCambridge J, McAlaney J, Rowe R. Adult consequences of late adolescent alcohol consumption: a systematic review of cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2011;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000413. e1000413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korczak D. Deutsches Institut für Medizinische Dokumentation und Information (DIMDI) Köln: 2012. Föderale Strukturen der Prävention von Alkoholmissbrauch bei Kindern und Jugendlichen. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isensee B, Maruska K, Hanewinkel R. Langzeiteffekte des Präventionsprogramms Klasse2000 auf den Substanzkonsum. Sucht. 2015;61:127–138. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morgenstern M, Wiborg G, Isensee B, Hanewinkel R. School-based alcohol education: results of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2009;104:402–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomczyk S, Hanewinkel R, Isensee B. ‚Klar bleiben‘: a school-based alcohol prevention programme for German adolescents-study protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2015;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010141. e010141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wechsler H, Nelson TF. Binge drinking and the American college student: what‘s five drinks? Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15:287–291. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tossmann P, Kasten L, Lang P, Strüber E. Bestimmung der konkurrenten Validität des CRAFFT-d Ein Screeninginstrument für problematischen Alkoholkonsum bei Jugendlichen. Z Kinder Jugendpsychiatr Psychother. 2009;37:451–459. doi: 10.1024/1422-4917.37.5.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woicik PA, Stewart SH, Pihl RO, Conrod PJ. The substance use risk profile scale: a scale measuring traits linked to reinforcement-specific substance use profiles. Addict Behav. 2009;34:1042–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foxcroft DR, Tsertsvadze A. Universal school-based prevention programs for alcohol misuse in young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011: doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009308. CD009113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraus L, Augustin R, Bloomfield K, Reese A. Der Einfluss regionaler Unterschiede im Trinkstil auf riskanten Konsum, exzessives Trinken, Missbrauch und Abhängigkeit. Gesundheitswesen. 2001;63:775–782. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Isensee B, Hanewinkel R. Meta-analysis on the effects of the smoke-free class competition on smoking prevention in adolescents. Eur Addict Res. 2012;18:110–115. doi: 10.1159/000335085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pahlke F, König IR, Ziegler A. Randomization in Treatment Arms (RITA): Ein Randomisierungs-Programm für klinische Studien. Inform Biom Epidemiol Med Biol. 2004;35:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faggiano F, Vigna-Taglianti F, Burkhart G, et al. The effectiveness of a school-based substance abuse prevention program: 18-month follow-up of the EU-Dap cluster randomized controlled trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eldridge SM, Ashby D, Kerry S. Sample size for cluster randomized trials: effect of coefficient of variation of cluster size and analysis method. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:1292–1300. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray DM, Varnell SP, Blitstein JL. Design and analysis of group-randomized trials: a review of recent methodological developments. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:423–432. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isensee B, Hansen J, Maruska K, Hanewinkel R. Effects of a school-based prevention programme on smoking in early adolescence: a 6-month follow-up of the ‚Eigenstandig werden‘ cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2014;4 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004422. e004422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Merritt RK, Farkas AJ. Validation of susceptibility as a predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychol. 1996;15:355–361. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.5.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuntsche E, Kuntsche S. Development and validation of the Drinking Motive Questionnaire Revised Short Form (DMQ-R SF) J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2009;38:899–908. doi: 10.1080/15374410903258967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young RM, Hasking PA, Oei TPS, Loveday W. Validation of the Drinking Refusal Self-Efficacy Questionnaire. Revised in an Adolescent Sample (DRSEQ-RA). Addict Behav. 2007;32:862–868. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Demmel R, Hagen J. Faktorenstruktur und psychometrische Eigenschaften einer gekürzten deutschsprachigen Version des Alcohol Expectancy Questionnaire (Brief AEQ-G) Z Different Diagn Psychol. 2002;23:205–216. [Google Scholar]