Abstract

Plant parasitic nematodes cause severe damage and yield loss in major crops all over the world. Available control strategies include use of insecticides/nematicides but these have proved detrimental to the environment, while other strategies like crop rotation and resistant cultivars have serious limitations. This scenario provides an opportunity for the utilization of technological advances like RNA interference (RNAi) to engineer resistance against these devastating parasites. First demonstrated in the model free living nematode, Caenorhabtidis elegans; the phenomenon of RNAi has been successfully used to suppress essential genes of plant parasitic nematodes involved in parasitism, nematode development and mRNA metabolism. Synthetic neurotransmitants mixed with dsRNA solutions are used for in vitro RNAi in plant parasitic nematodes with significant success. However, host delivered in planta RNAi has proved to be a pioneering phenomenon to deliver dsRNAs to feeding nematodes and silence the target genes to achieve resistance. Highly enriched genomic databases are exploited to limit off target effects and ensure sequence specific silencing. Technological advances like gene stacking and use of nematode inducible and tissue specific promoters can further enhance the utility of RNAi based transgenics against plant parasitic nematodes.

Keywords: plant parasitic nematodes, host delivered RNAi, root-knot nematodes, cyst nematodes, dsRNA, siRNA

Introduction

Plant parasitic nematodes (PPNs) have emerged as a severe threat to crop production and are responsible for an estimated loss of US $173 billion annually to world agriculture (Elling, 2013). In addition to the direct damage caused to the plants, nematode infection facilitates subsequent attack by other plant pathogens such as bacteria and fungi. Sedentary endoparasites are the most significant and economically damaging PPNs which include the genera Meloidogyne [root-knot nematodes (RKNs)], Heterodera and Globodera [Cyst Nematodes (CNs)]. The RKNs have a broad host range and form characteristic root galls on the host roots, while CNs have a comparatively constricted host range. The life cycles of these parasites are characteristically different from each other involving complex interactions with their hosts (Williamson and Gleason, 2003). However, both CNs and RKNs inject their salivary secretions in plant cells and withdraw nutrients (Atkinson et al., 1988; Li et al., 2011) by forming multi-cellular feeding sites called syncytia and giant cells, respectively. The infected plants remain stunted, show wilting symptoms and become prone to enhanced susceptibility to other diseases (Fairbairn et al., 2007). Migratory endoparasitic nematodes such as Radopholus spp. and Pratylenchus spp. are also highly damaging as in contrast to sedentary endoparasites, the migratory endoparasites remain motile and migrate through the course of their development.

Various methods have been used for management of PPNs including development of resistant cultivars, chemical nematicides and cultural practices. Use of nematicides as means of chemical control has been most effective in managing PPNs. However, detrimental effects of the major nematicides on environment and human health have compelled various developed and developing countries to impose bans on their use. Nematode resistant genes are present in some cultivars of species like tomato, potato and soybean but they are only limited to specific pathotypes while many crops do not have the presence of resistance loci (Fairbairn et al., 2007). This situation leads us to utilize technological advancements like RNA interference (RNAi) for engineering resistance against important nematode pests in crop plants. RNAi refers to sequence specific and homology-dependent gene silencing through a complex mechanism in which double stranded RNA (dsRNA) is recognized which leads to a chain of events resulting in the degradation of both the dsRNA and homologous RNA. Since its first description in Caenorhabtidis elegans (Fire et al., 1998), this highly conserved mechanism of RNAi has been demonstrated in various organisms belonging to different species across the animal and plant kingdoms (Jones et al., 2011). After the onset of RNAi by exogenous dsRNA, the intestinal epithelial cells of the nematodes are generally involved in dsRNA uptake. In case, there is no expression of the target gene in the uptake cells, silencing of the target transcript is systematically spread to more distant cells (Whangbo and Hunter, 2008). The most imperative aspect of RNA interference is that, it is highly precise, remarkably powerful and the interference can be caused in cells and tissues far away from the site of introduction (Rosso et al., 2009; Tomoyasu et al., 2008).

RNAi in PPNs by soaking in dsRNA solutions

In vitro RNAi has been successfully demonstrated in CNs (Urwin et al., 2002), RKNs (Rosso et al., 2005) and even migratory nematodes (Haegeman et al., 2009; Soumi et al., 2012; Li et al., 2015) by feeding dsRNA solutions. Three different methods have been used in C. elegans for introduction of dsRNA which include feeding on bacteria expressing target gene dsRNA (Timmons and Fire, 1998; Kamath et al., 2001; Timmons et al., 2001), soaking of nematodes in dsRNA solution facilitating its oral uptake (Tabara et al., 1998) and microinjection (Fire et al., 1998; Mello and Conte, 2004). But, in case of PPNs, microinjection has not been effective because of the small size of the infective stages and their inability to ingest fluid without host plant infection. However, a variety of technical and chemical advances have successfully enhanced efficient dsRNA uptake from solutions by soaking. Urwin et al. (2002) first demonstrated in vitro RNAi in PPNs successfully by using a neuroactive compound, octopamine to facilitate dsRNA uptake by second stage juveniles (J2s) of CNs H. glycines and G. palida. In further studies, induction of dsRNA uptake by Meloidogyne incognita J2s was enhanced by using the same method (Bakhetia et al., 2005; Shingles et al., 2007). In other studies, resorcinol and serotonin were used for successful uptake of dsRNA in M. incognita (Rosso et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2006) and lipofectin was used in case of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus (Park et al., 2008). Fluoroscein isothiocyanate (FITC) have been used as a visual marker for monitoring dsRNA uptake and selection of individuals in various studies (Urwin et al., 2002; Rosso et al., 2005; Dutta et al., 2015b).

Different time periods of exposure of J2s to dsRNA in a range of 1 h to 7 days have been employed in different studies. For the knockdown of Mi-gsts-1, M. incognita J2s were incubated with Mi-gsts-1 dsRNA for 1 h with 90% reduction in the transcript expression (Dubreuil et al., 2007). Bakhetia et al. (2005) demonstrated highly efficient in vitro dsRNA uptake by J2s of M. incognita with 4 h incubation period. However, further studies showed increase in transcript reduction resulting in desired phenotypic effects with increase in the incubation time (Kimber et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2011). Majority of the reports showing in vitro dsRNA soaking have not assessed the stability of the resulting gene knock down. However, the efficiency and duration of the silencing effect was assessed for M. incognita calreticulin (Mi-crt) and polygalacturonase (Mi-pg-1) by Rosso et al. (2005). The transcript repression was highest at 20 and 44 h after soaking into dsRNA solution for Mi-crt and Mi-pg-1 respectively. However, the silencing effect was not detectable for both the genes 68 h after soaking. In H. glycines, the reduction in the transcript levels of β-1,4- endoglucanase was observed immediately after an incubation of 16 h with the corresponding dsRNA and after 15 days of dsRNA treatment, the transcript levels returned to normal (Bakhetia et al., 2007). These reports suggest that the silencing achieved due to soaking in dsRNA solutions is often transient and lack stability. In general, it can be concluded that the soaking method is an efficient tool for identification of gene function and expression. However, the obligate parasitic nature of plant parasitic nematodes and their exclusivity to feed on plant cells throughout their life cycle inside the host makes in planta RNAi technology a suitable approach to combat plant parasitic nematodes. The advantage of the host delivery strategy is that it provides a continuous availability of the dsRNA to the nematode, thereby making the chances of gene suppression reversal remote.

Host generated RNAi to silence nematode specific genes

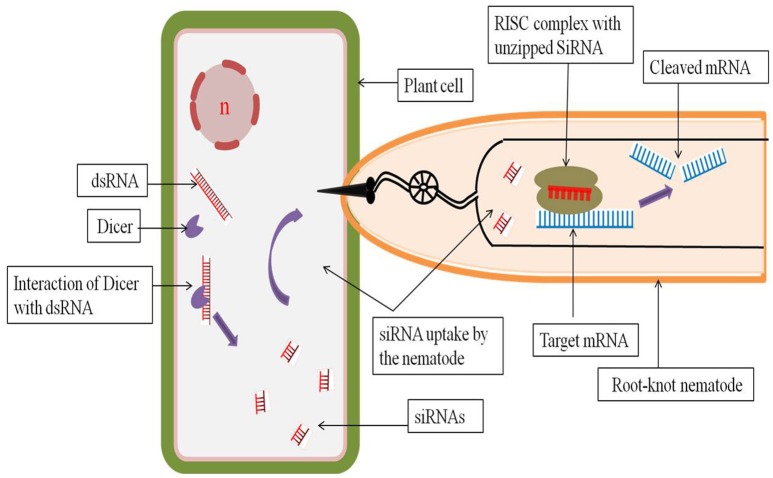

Host generated RNAi has proved to be a revolutionary approach for the delivery of dsRNAs or siRNAs into the feeding nematodes for the silencing of vital nematode specific genes. Purposely, those genes should be targeted whose expression is essential for the nematodes after the feeding starts to ensure a highly lethal phenotype. A dsRNA construct for the target gene is developed by cloning a part of the target gene cDNA in sense and antisense orientation separated by an intron or spacer region. A strong tissue specific or constitutive promoter may be used to drive the expression of the dsRNA. Transcription of the sense and antisense strands results in the formation of a self-complimentary hairpin structure with the removal of the intron by splicing (Smith et al., 2000). The dsRNAs so formed can either be directly ingested by the PPNs or can be processed by the host plant's own RNAi machinery and the resulting siRNAs can be subsequently ingested by the PPNs (Bakhetia et al., 2005; Dutta et al., 2015a; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Host generated RNAi through interaction between host plant cell and root-knot nematode. The dsRNA introduced into the host plant is recognized by the cellular RNAse III type enzyme dicer, which cuts the dsRNA into shorter fragments of 20–25 nucleotides called siRNAs. During infection into the host, the nematode ingests the siRNAs through its stylet. These host derived siRNAs are then processed by the nematode RNAi machinery where the unzipped siRNAs bound to the RISC complex cleaves the target mRNA in a sequence specific manner and inhibits further translation of the target mRNA.

Host generated RNAi has been demonstrated by targeting different nematode genes which may be broadly classified under three categories: housekeeping genes, parasitism or effector genes and genes associated with nematode development. Yadav et al. (2006) first demonstrated host delivered RNAi in tobacco to silence two nematode specific housekeeping genes; splicing factor and integrase of M. incognita. They reported more than 90% reduction in established nematodes in both the cases of host generated RNAi. Since then, host generated RNAi has been effectively demonstrated against PPNs by various groups of scientists all over the world (Table 1). Recently, Kumar et al. (2017) reconfirmed the utility of splicing factor and integrase as lethal RNAi targets for M. incognita by demonstrating significant reduction in number of galls, females and egg masses by targeting these genes for host generated RNAi in A. thaliana. Silencing of some of the other housekeeping genes like ribosomal protein 3a, ribosomal protein 4, spliceosomal SR protein, Mi-Rpn7, Prp-17 etc. have resulted in substantial reduction in number and parasitism of incursive PPNs (Klink et al., 2009; Li et al., 2010b; Niu et al., 2012). In an innovative approach toward gene stacking, host generated RNAi was used to obtain combined resistance against migratory root lesion nematode, Pratylenchus vulnus and crown gall in walnut through co-transformation (Walawage et al., 2013). They used A. tumefaciens carrying self-complementary iaaM and ipt transgenes and A. rhizogenes carrying Pv010 gene from P. vulnus for co-transformation. Most of the reports involving nematode housekeeping genes indicate their effectiveness as efficient targets for host generated RNAi. However, silencing of a putative transcription factor of M. javanica, MjTis11 through host generated RNAi in tobacco did not result in lethal phenotypic effect on the nematodes (Fairbairn et al., 2007). siRNA generation was detected in the transgenic plants confirming the successful processing of the delivered dsRNAs. Therefore, it can be concluded that either this gene is not a suitable candidate for host generated RNAi or the achieved downregulation levels of the transcript is not sufficient to generate lethal phenotypic effects. The unsuitability of genes as targets for host generated RNAi can possibly result from the genetic redundancy of such genes.

Table 1.

Host generated RNAi in plant parasitic nematodes.

| Target gene | Nematode species | Host plant | promoter | phenotype | Time point | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integrase | M. incognita | Tobacco | 35S | >90% reduction in number of established nematodes | 6–7 weeks after infection | Yadav et al., 2006 |

| Splicing factor | M. incognita | Tobacco | 35S | >90% reduction in number of established nematodes | 6–7 weeks after infection | Yadav et al., 2006 |

| Secreted peptide 16D10 | M. incognita | Arabidopsis | 35S | 63–90% reduction in number of galls and gall size | 4 weeks after infection | Huang et al., 2006 |

| M. arenaria | ||||||

| M. javanica | ||||||

| M. hapla | ||||||

| Major sperm protein | H. glycines | Soybean | ACT2 | Upto 68% reduction in number of eggs | 8 weeks after infection | Steeves et al., 2006 |

| Putative transcription factor | M. javanica | Tobacco | 35S | None | 6 weeks after infection | Fairbairn et al., 2007 |

| Ribosomal protein 3a | H. glycines | Soybean | FMV-sgt | 87% reduction in number of female cysts | 8 days after infection | Klink et al., 2009 |

| Ribosomal protein 4 | H. glycines | Soybean | FMV-sgt | 81% reduction in number of female cysts | 8 days after infection | Klink et al., 2009 |

| Spliceosomal SR protein | H. glycines | Soybean | FMV-sgt | 88% reduction in number of female cysts | 8 days after infection | Klink et al., 2009 |

| 4G06, Ubiquitin-like | H. schachtii | Arabidopsis | 35S | 23–64% reduction in number of developing females | 14 days after infection | Sindhu et al., 2009 |

| 3B05, cellulose binding protein | H. schachtii | Arabidopsis | 35S | 12–47% reduction in number of developing females | 14 days after infection | Sindhu et al., 2009 |

| 8H07, SKP1-like | H. schachtii | Arabidopsis | 35S | >50% reduction in number of developing females | 14 days after infection | Sindhu et al., 2009 |

| 10AO6, Zinc finger protein | H. schachtii | Arabidopsis | 35S | 42% reduction in number of developing females | 14 days after infection | Sindhu et al., 2009 |

| Y25, beta subunit of COPI complex | H. glycines | Soybean | 35S | 81% reduction in number of nematode eggs | 5 weeks after infection | Li et al., 2010a,b |

| Prp-17, Pre-mRNA splicing factor | H. glycines | Soybean | 35S | 79% reduction in number of nematode eggs | 5 weeks after infection | Li et al., 2010b |

| Cpn-1 | H. glycines | Soybean | 35S | 95% reduction in number of nematode eggs | 5 weeks after infection | Li et al., 2010b |

| Rpn7 | M. incognita | Tomato | 35S | Reduction in motility and infectivity of J2s | 40 days after infection | Niu et al., 2012 |

| AF531170, parasitism gene | M. incognita | Tomato | 35S | 54–59% reduction in number of developing females | 7, 21, 30 days after infection | Choudhary et al., 2012 |

| 8D05, Parasitism gene | M. incognita | Arabidopsis | 35S | Reduction in number of galls | 8 weeks after infection | Xue et al., 2013 |

| flp-14, FMRF amide like peptide | M. incognita | Tobacco | 35S | Reduction in parasitic ability from 67–86% | 30 days after infection | Papolu et al., 2013 |

| flp-18, FMRF amide like peptide | M. incognita | Tobacco | 35S | Reduction in parasitic ability from 53–82% | 30 days after infection | Papolu et al., 2013 |

| Mi-ser-1, serine protease | M. incognita | Tobacco | 35S | Reduction in number of eggs per gram of root. Reduction in egg hatching ratio | 28 days after infection | Antonino de Souza Júnior et al., 2013 |

| Mi-cpl-1, Cysteine protease | M. incognita | Tobacco | 35S | Reduction in number of eggs per gram of root. | 28 days after infection | Antonino de Souza Júnior et al., 2013 |

| Mi-asp-1+Mi-ser-1+Mi-cpl-1 (fusion) | M. incognita | Tobacco | 35S | Reduction in number of eggs per gram of root. | 28 days after infection | Antonino de Souza Júnior et al., 2013 |

| Pv010 | P. vulnus | Walnut | 35S | Reduction in number of nematodes | 60 days after infection | Walawage et al., 2013 |

| Mc16D10L | M. chitwoodi | Potato | 35S | 65–68% Reduction in the number of egg masses | 35, 55 days after infection | Dinh et al., 2014b |

| Mc16D10L | M. chitwoodi | Arabidopsis | 35S | 57 and 67% reduction in number of egg masses and eggs respectively | 35, 55 days after infection | Dinh et al., 2014a |

| Mi-cpl-1 | M. incognita | Tomato | 35S | 60–80% reduction in infection and multiplication | 35 days after infection | Dutta et al., 2015b |

| Pp-pat-10 | P. penetrans | Soybean | 35S | Upto 40% reduction in number of nematodes | 3 months after infection | Vieira et al., 2015 |

| Pp-unc-87 | P. penetrans | Soybean | 35S | Upto 50% reduction in number of nematodes | 3 months after infection | Vieira et al., 2015 |

| Rs-cb-1 | R. similis | Tobacco | 35S | Reduced reproduction and pathogenicity | 75 days after infection | Li et al., 2015 |

| HSP90, Heat Shock Protein | M. incognita | Tobacco | 35S | Delayed gall formation and upto 46% reduction in the number of eggs | Lourenço-Tessutti et al., 2015 | |

| ICL, Isocitrate lyase | M. incognita | Tobacco | 35S | Upto 77% reduction in egg oviposition | Lourenço-Tessutti et al., 2015 | |

| Unc-15 | Ditylenchus destructor | Sweet potato | 35S | 50% reduction in the infection area | 45 days after infection | Fan et al., 2015 |

| MeTCTP | M. enterolobii | Tomato | 35S | Reduction in number of nematodes | 15 and 30 days after infection | Zhuo et al., 2017 |

| MiMSP40 | M. incognita | Arabidopsis | 35S | Reduction in the number of galls | 7 weeks after infection | Niu et al., 2016 |

Both, in vitro and in vivo RNAi approaches were used to silence a parasitism gene, 16D10, expressed in the subventral gland cells of M. incognita leading to substantial reduction in the number of galls in the range of 63–90% in Arabidopsis (Huang et al., 2006). In addition, the gall size also decreased leading to reduction in the total number of eggs as compared to control. Mc16D10L was also targeted for host delivered RNAi in potato and Arabidopsis against M. chitwoodi by Dinh et al. (2014a,b) leading to significant reduction in nematode numbers in terms of the number of eggs and egg masses. They also reported substantial reduction in target gene expression in the second generation M. chitwoodi eggs and J2s which demonstrates transmission of the RNAi effect into the progenies. 16D10 is conserved among the Meloidogyne spp. which further makes it a suitable target for engineering resistance against a broader range of PPNs. Parasitism of PPNs was successfully suppressed by targeting some other parasitism or effector genes like 4G06, 3B05, 8H07, 10AO6, AF531170, 8D05, MeTCTP etc. through host generated RNAi (Sindhu et al., 2009; Choudhary et al., 2012; Xue et al., 2013; Zhuo et al., 2017). Recently, M. incognita effector MiMSP40 was reported to facilitate parasitism through manipulation of plant immunity (Niu et al., 2016). Overexpression of MiMSP40 lead to increased susceptibility in Arabidopsis, while host generated RNAi of MiMSP40 resulted in reduction in parasitism and reproductive potential of M. incognita. Similarly, overexpression of M. enterolobii effector MeTCTP imparted increased susceptibility. Conversely, in planta RNAi targeting MeTCTP caused attenuated parasitism in Arabidopsis (Zhuo et al., 2017). Therefore, recent reports indicate the suitability of nematode effector genes as targets for host generated RNAi to achieve resistance.

Genes involved in nematode development and reproduction are often targeted with considerable success in hindering the development and reproductive potential of PPNs (Steeves et al., 2006; Charlton et al., 2010; Antonino de Souza Júnior et al., 2013; Papolu et al., 2013; Dutta et al., 2015b). Decreased number of eggs was phenotypically observed by targeting a major sperm protein from H. glycines for host generated silencing in soybean (Steeves et al., 2006). Silencing of the major sperm protein hampered the reproductive potential of H. glycines which continued to the next generation of the nematodes as the progeny also showed an impaired ability to reproduce successfully. FMRF amide like neuropeptides were targeted for silencing through in vitro and in vivo RNAi by Papolu et al. (2013). Transgenic tobacco lines expressing flp-14 and flp-18 dsRNAs showed significant reduction in the range of 50–80% in the infection and multiplication of M. incognita. This study proved that neuropeptides can be exploited as potential targets for host delivered RNAi considering the involvement of these genes in nematode physiology including locomotion, feeding, parasitism and reproduction. In vitro silencing of carrying cathepsin L cysteine proteinase (Mi-cpl-1), led to reduced attraction and penetration of M. incognita in tomato suggesting its role in nematode parasitism (Dutta et al., 2015b).

The development of dsRNA constructs for host delivered RNAi through conventional methods have been a time taking and tedious. Therefore, a much easier, quick and effective process of gateway cloning system has been employed by different groups for the development of RNAi constructs (Klink et al., 2009; Papolu et al., 2013; Dutta et al., 2015b). A. rhizogenes mediated hairy root method for transformation in crops like tomato (Remeeus et al., 1998), soybean (Klink et al., 2009; Li et al., 2010b) and sugar beet (Kifle et al., 1999; Cai et al., 2003) has been instrumental for rapid screening of the target genes. The genes found effective through hairy root transformation can further be utilized for the development of stable transgenic plants through A. tumifeciens mediated transformation. The studies on host delivered RNAi have showed that the success in obtaining significant degree of resistance depends on the role of the target gene and the degree of transcript knockdown. However, of all the strategies implied till date to achieve resistance against PPNs, host-delivered RNAi appears to provide more effective resistance when it targets nematode genes involved in essential cellular processes.

Biosafety aspects

Application of RNAi for management of PPNs needs thorough risk assessment and proper designing of the experiments to overcome the limitations. Avoiding off-target effects is an important consideration for all RNAi experiments. Off target effects can originate due to sequence identity between dsRNA and non target mRNA transcripts resulting in a compromised specificity of RNAi and false interpretation of the resulting phenotype. According to Rual et al. (2007); in C. elegans, a sequence of mRNA having more than 95% identity with the dsRNA for over 40 nucleotides results in off-target effects. Unexpected and unintended gene silencing in the plant may lead to harmful and deleterious effects on its phenotype and physiology and can cause serious environmental consequences. Xing and Zachgo (2007) explained the phenomenon of pollen lethality in Arabidopsis where surprising pleiotropic effects such as reduced pollen viability was observed due to RNAi, however other plant growth parameters were found to be normal. Apart from these off target effects, non-target organisms may encounter harmful non target effects of RNAi on being exposed to the plant parts or debris of genetically modified plants through RNAi. Therefore, development of strategies for preventing the off-target and non-target effects is a crucial biosafety consideration for a wider employment of RNAi as a novel tool in plant disease management.

Availability of suitable genomic databases can be utilized extensively for in silico homology searches for selection of target genes to avoid off-target effects (Banerjee et al., 2017). Genes showing high degree of sequence conservation among plant and animal kingdom should be avoided and use of species specific targets should be encouraged. The 5′-3′ untranslated regions (UTR) sequences can also be used as siRNA targets owing to their less degree of conservation as compared to coding regions. Thorat et al. (2016) used a nematode responsive and root specific promoter of Arabidopsis origin to transform tomato with a GUS reporter gene. A strong GUS activity was reported at nematode infection site starting from 10 days up to 21 days post infection. Further, this promoter was used to drive the expression of M. incognita splicing factor dsRNA and upon transformation in tomato; 50–70% reduction in nematode galls over the control plant was reported. This strategy of using root specific and/or nematode inducible promoters can avoid the expression of siRNAs in undesirable parts of the plants.

Conclusion and future prospects

RNAi has emerged as a powerful strategy to control multiple pest and pathogens including nematodes especially as we are moving toward the goal of phasing out chemicals that are harmful to environments and ecosystems. Management of nematodes however, presents some unique challenges as these are obligatory parasites requiring living host for feeding. The use of host induced RNAi to combat plant pathogenic nematodes has so far been effective especially with respect to RKNs and CNs. The advancement in the area of functional genomics availability of genome sequence data and new bioinformatics tools have enabled design and engineering of effective dsRNA expression constructs addressing concerns of off-target silencing. Stacking of dsRNA sequences to target multiple genes has emerged as an attractive proposition for effective nematode control. Use of nematode induced and plant tissue specific promoters limiting dsRNA gene expressions to specific plant tissue/s in response to particular nematode can also mitigate biosafety concerns. The ability to precisely edit genomes is rapidly transforming the landscape of novel ways to target plant pathogens. CRISPR/Cas system is emerging as a powerful approach for loss of function analysis, insights into host–parasite and parasite–vector interactions, and the genetic basis of parasitism. A number of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing protocols have been established in C. elegans (Friedland et al., 2013) opening new doors to studying the biology of closely related nematode parasites. Translation of CRISPR/Cas9 technology from C. elegans to Strongyloides spp., Ascaris suum, Brugia malayi and Haemonchus contortus have been recently outlined (Ward, 2015; Britton et al., 2016; Zamanian and Andersen, 2016). Recent reports on topical application of dsRNA for resistance against viruses using layered double hydroxide clay nanosheets (Mitter et al., 2017) opens up possibilities to exploit such innovations for specific and combinatorial resistance against PPNs, insects and plant pathogenic fungi.

Author contributions

SB, AB, SG, OG, and AS drafted the manuscript. SB and AB collected background information. SG, PJ, AD, and AS critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) through National Agricultural Innovative Project (NAIP/C4/C1092) and National Fund for Basic Strategic and Frontier Application Research in Agriculture (NFBSFARA/RNA-3022/2012-13). The authors apologize to colleagues whose work could not be cited due to space constraints.

References

- Antonino de Souza Júnior J. D., Ramos Coelho R., Tristan Lourenço I., da Rocha Fragoso R., Barbosa Viana A. A., Lima Pepino de Macedo L., et al. (2013). Knocking- down Meloidogyne incognita proteases by plant-delivered dsRNA has negative pleiotropic effect on nematode vigor. PLoS ONE 8:e85364. 10.1371/journal.pone.0085364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson H. J., Harris P. D., Halk E. J., Novitski C., Leighton-Sands J., Nolan P., et al. (1988). Monoclonal antibodies to the soya bean cyst nematode, Heterodera glycines. Ann. Appl. Biol. 112, 459–469. 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1988.tb02083.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhetia M., Charlton W., Atkinson H. J., McPherson M. J. (2005). RNA interference of dual oxidase in the plant nematode Meloidogyne incognita. Mol. Plant Microb. Interact. 18, 1099–1106. 10.1094/MPMI-18-1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakhetia M., Urwin P. E., Atkinson H. J. (2007). qPCR analysis and RNAi define pharyngeal gland cell-expressed genes of Heterodera glycines required for initial interactions with the host. Mol. Plant Microb. Interact. 20, 306–312 10.1094/mpmi-20-3-0306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Gill S. S., Jain P. K., Sirohi A. (2017). Isolation, cloning, and characterization of a cuticle collagen gene, Mi-col-5, in Meloidogyne incognita. 3 Biotech 7:64. 10.1007/s13205-017-0665-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton C., Roberts B., Marks N. (2016). Functional genomics tools for Haemonchus contortus and lessons From Other Helminths. Adv. Parasitol. 93, 599–623. 10.1016/bs.apar.2016.02.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai D., Thurau T., Tian Y., Lange T., Yeh K. W., Jung C. (2003). Sporamin-mediated resistance to beet cyst nematodes (Heterodera schachtii Schm.) is dependent on trypsin inhibitory activity in sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.) hairy roots. Plant. Mol. Biol. 51, 839–849. 10.1023/A:1023089017906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton W. L., Harel H. Y. M., Bakhetia M., Hibbard J. K., Atkinson H. J., Mcpherson M. J. (2010). Additive effects of plant expressed double-stranded RNAs on root-knot nematode development. Int. J. Parasitol. 40, 855–864. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary D., Koulagi R., Rohatagi D., Kumar A., Jain P. K., Sirohi A. (2012). Engineering resistance against root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita, by host delivered RNAi, in Abstracts of International Conference on Plant Biotechnology for food Security: New Frontiers (New Delhi: National Agricultural Science Centre; ), 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh P. T. Y., Brown C. R., Elling A. A. (2014a). RNA interference of effector gene Mc16D10L confers resistance against Meloidogyne chitwoodi in Arabidopsis and Potato. Phytopathology 104, 1098–1106. 10.1094/PHYTO-03-14-0063-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh P. T. Y., Zhang L., Brown C. R., Elling A. A. (2014b). Plant-mediated RNA interference of effector gene Mc16D10L confers resistance against Meloidogyne chitwoodi in diverse genetic backgrounds of potato and reduces pathogenicity of nematode offspring. Nematology 6, 669–682. 10.1163/15685411-00002796 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil G., Magliano M., Deleury E., Abad P., Rosso M. N. (2007). Transcriptome analysis of root knot nematode functions induced in early stage of parasitism. New Phytol. 176, 426–436. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02181.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta T. K., Bankar P., Rao U. (2015a). The status of RNAi-based transgenic research in plant nematology. Front. Microbiol. 5:760. 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta T. K., Papolu P. K., Banakar P., Choudhary D., Sirohi A., Rao U. (2015b). Tomato transgenic plants expressing hairpin construct of a nematode protease gene conferred enhanced resistance to root-knot nematodes. Front. Microbiol. 6:260. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elling A. A. (2013). Major emerging problems with minor Meloidogyne species. Phytopathology 103, 1092–1102. 10.1094/PHYTO-01-13-0019-RVW [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbairn D. J., Cavallaro A. S., Bernard M., Mahalinga-Iyer J., Graham M. W., Botella J. R. (2007). Host-delivered RNAi: an effective strategy to silence genes in plant parasitic nematodes. Planta 226, 1525–1533 10.1007/s00425-007-0588-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W., Wei Z., Zhang M., Ma P., Liu G., Zheng J., et al. (2015). Resistance to Ditylenchus destructor infection in sweet potato by the expression of small interfering RNAs targeting unc-15, a movement-related gene. Phytopahology 105, 1458–1465. 10.1094/PHYTO-04-15-0087-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A., Xu S., Montgomery M. K., Kostas S. A., Driver S. E., Mello C. C. (1998). Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 391, 806–811. 10.1038/35888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedland A. E., Tzur Y. B., Esvelt K. M., Colai acovo M. P., Church G. M., Calarco J. A. (2013). Heritable genome editing in C. elegans via a CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Methods 10, 741–743. 10.1038/nmeth.2532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haegeman A., Vanholme B., Gheysen G. (2009). Characterization of putative endoxyalanase in the migratory plant-parasitic nematode Rhodopholus similis. Mol. Plant Pathol. 10, 389–401. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00539.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G., Allen R., Davis E. L., Baum T. J., Hussey R. S. (2006). Engineering broad root-knot resistance in transgenic plants by RNAi silencing of a conserved and essential root-knot nematode parasitism gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 14302–14306. 10.1073/pnas.0604698103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones L. M., Giorgi C. D., Urwin P. E. (2011). C. elegans as a resource for studies on plant parasitic nematodes, in Genomics and Molecular Genetics of Plant-nematode Interactions, eds Jones J., Gheysen G., Fennoll C. (New York, NY: Springer; ), 175–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kamath R. S., Martinez-Campos M., Zipperlen P., Fraser A. G., Ahringer J. (2001). Effectiveness of specific RNA-mediated interference through ingested double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Biol. 2, research 0002.1–2.10. 10.1186/gb-2000-2-1-research0002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kifle S., Shao M., Jung C., Cai D. (1999). An improved transformation protocol for studying gene expression in hairy roots of sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.). Plant Cell Rep. 18, 514–519. 10.1007/s002990050614 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber M. J., McKinney S., McMaster S., Day T. A., Flemming C. C., Maule A. G. (2007). Flp gene disruption in a parasitic nematode reveals motor disfunction and unusual neuronal sensitivity to RNA interference. FASEB J. 21, 1233–1243. 10.1096/fj.06-7343com [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klink V. P., Kim K. H., Martins V., Macdonald M. H., Beard H. S., Alkharouf N. W., et al. (2009). A correlation between host-mediated expression of parasite genes as tandem inverted repeats and abrogation of development of female Heterodera glycines cyst formation during infection of Glycine max. Planta 230, 53–71. 10.1007/s00425-009-0926-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Kakrana A., Sirohi A., Subramaniam K., Srinivasan R., Abdin M. Z., et al. (2017). Host-delivered RNAi-mediated root-knot nematode resistance in Arabidopsis by targeting splicing factor and integrase genes. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 83, 91–97. 10.1007/s10327-017-0701-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Todd T. C., Lee J., Trick H. N. (2011). Biotechnological application of functional genomics towards plant parasitic nematode control. Plant Biotech. J. 9, 936–944. 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00601.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Todd T. C., Oakley T. R., Lee J. L., Trick H. N. (2010a). Host-derived suppression of nematode reproductive and fitness genes decreases fecundity of Heterodera glycines Ichinohe. Planta 232, 775–785. 10.1007/s00425-010-1209-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Todd T. C., Trick H. N. (2010b). Rapid in planta evaluation of root expressed transgenes in chimeric soybean plants. Plant Cell Rep. 29, 113–123. 10.1007/s00299-009-0803-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Wang K., Xie H., Wang D. W., Xu C. L., Huang X., et al. (2015). Cathepsin B Cysteine Proteinase is Essential for the Development and Pathogenesis of the Plant Parasitic Nematode Radopholus similis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 11, 1073–1087. 10.7150/ijbs.12065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lourenço-Tessutti I. T., Souza Junior J. D. A., Martins-de-Sa D., Viana A. A. B., Carneiro R. M. D. G., Togawa R. C., et al. (2015). Knock-down of heat-shock protein 90 and isocitrate lyase gene expression reduced root-knot nematode reproduction. Phytopathology 105, 628–637 10.1094/PHYTO-09-14-0237-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello C. C., Conte D., Jr. (2004). Revealing the world of RNA interference. Nature 431, 338–342. 10.1038/nature02872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitter N., Worrall E. A., Robinson K. E., Li P., Jain R. G., Taochy C., et al. (2017). Clay nanosheets for topical delivery of RNAi for sustained protection against plant viruses. Nat. plants 3:16207. 10.1038/nplants.2016.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu J. H., Jian H., Xu J., Chen C., Guo Q. (2012). RNAi silencing of the Meloidogyne incognita Rpn7 gene reduces nematode parasitic success. Euro. J. Plant Pathol. 134, 131–144. 10.1007/s10658-012-9971-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niu J., Liu P., Liu Q., Chen C., Guo Q., Yin J., et al. (2016). Msp40 effector of root-knot nematode manipulates plant immunity to facilitate parasitism. Sci. Rep. 6:19443. 10.1038/srep19443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papolu P. K., Gantasala N. P., Kamaraju D., Banakar P., Sreevathsa R., Rao U. (2013). Utility of host delivered RNAi of two FMRF amide like peptides, flp-14 and flp-18, for the management of root knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita. PLoS ONE 8:e80603. 10.1371/journal.pone.0080603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. E., Lee K. Y., Lee S. J., Oh W. S., Jeong P. Y., Woo T., et al. (2008). The efficiency of RNA interference in Bursaphelenchus xylophilus. Mol. Cells 26, 81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remeeus P. M., Bezooijen J. V., Wijbrandi J. (1998). In vitro testing is a reliable way to screen the temperature sensitivity of resistant tomatoes against Meloidogyne incognita, in Proceedings of 5th International Symposium on Crop Protection, Universiteit Gent Vol. 63, (Ghent: ), 635–640. [Google Scholar]

- Rosso M. N., Dubrana M. P., Cimbolini N., Jaubert S., Abad P. (2005). Application of RNA interference to root-knot nematode genes encoding esophageal gland proteins. Mol. Plant Microb. Interact. 18, 615–620. 10.1094/MPMI-18-0615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosso M. N., Jones J. T., Abad P. (2009). RNAi and functional genomics in plant parasitic nematodes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 47, 207–232. 10.1146/annurev.phyto.112408.132605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rual J. F., Klitgord N., Achaz G. (2007). Novel insights into RNAi off-target effects using C. elegans paralogs. BMC Genomics 8:106. 10.1186/1471-2164-8-106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shingles J., Lilley C. J., Atkinson H. J., Urwin P. E. (2007). Meloidogyne incognita: molecular and biochemical characterization of a cathepsin L cysteine proteinase and the effect on parasitism following RNAi. Exp. Parasitol. 115, 114–120. 10.1016/j.exppara.2006.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindhu A., Maier T. R., Mittchum M. G., Hussey R. S., Davis L. R., Baum J. T. (2009). Effective and specific in planta RNAi in cyst nematodes: expression interference of four parasitism genes reduces parasitic success. J. Exp. Bot. 1, 315–324. 10.1093/jxb/ern289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith N. A., Singh S. P., Wang M. B., Stoutjesdijk P. A., Green A. G., Waterhouse P. M. (2000). Gene expression: total silencing by intron-spliced hairpin RNAs. Nature 407, 319–320. 10.1038/35036500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soumi J., Gheysen G., Subramaniam K. (2012). RNA interference in Pratylenchus coffeae: knockdown of Pc-pat-10 and Pc-unc-87 impedes migration. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 186, 51–59. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeves R. M., Todd T. C., Essig J. S., Trick H. N. (2006). Transgenic soybeans expressing siRNAs specific to a major sperm protein gene suppress Heterodera glycines reproduction. Func. Plant Biol. 33, 991–999. 10.1071/FP06130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabara H., Grishok A., Mello C. C. (1998). RNAi in C. elegans: soaking in the genome sequence. Science 282, 430–431. 10.1126/science.282.5388.430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorat Y., Kumar A., Jain P. K., Sirohi A. (2016). Development of root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita specific gene expression system in tomato, Solanum lycopersicum L., in Abstracts of 3rd International IUPAC Conference on Agrochemicals Protecting Crops, Health and Natural Environment: New Chemistries for Phytomedicines and Crop Protection Chemicals (New Delhi: ). [Google Scholar]

- Timmons L., Court D. L., Fire A. (2001). Ingestion of bacterially expressed dsRNAs can produce specific and potent genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene 263, 103–112. 10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00579-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons L., Fire A. (1998). Specific interference by ingested dsRNA. Nature 395:854. 10.1038/27579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomoyasu Y., Miller S., Tomita S., Schoppmeier M., Grossmann D., Bucher G. (2008). Exploring systemic RNA interference in insects: a genome-wide survey for RNAi genes in Tribolium. Genome Biol. 9:R10. 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urwin P. E., Lilley C. J., Atkinson H. J. (2002). Ingestion of double-stranded RNA by pre-parasitic juvenile cyst nematodes leads to RNA interference. Mol. Plant Microb. Interact. 15, 747–752. 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.8.747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira P., Eves-van den Akker S., Verma R., Wantoch S., Eisenback J. D., Kamo K. (2015). The Pratylenchus penetrans transcriptome as a source for the development of alternative control strategies: mining for putative genes involved in parasitism and evaluation of in planta RNAi. PLoS ONE 10:e0144674. 10.1371/journal.pone.0144674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walawage S. L., Britton M. T., Leslie C. A., Uratsu S. L., Li Y., Dandekar M. (2013). Stacking resistance to crown gall and nematodes in walnut rootstocks. BMC Genomics 14:668. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J. D. (2015). Rendering the intractable moretractable: tools from Caenorhabditis elegans ripe for import into parasitic nematodes. Genetics 201, 279–1294.71. 10.1534/genetics.115.182717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whangbo J. S., Hunter C. P. (2008). Environmental RNA interference. Trends Gen. 24, 297–305. 10.1016/j.tig.2008.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson V. M., Gleason C. A. (2003). Plant–nematode interactions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 6, 327–333. 10.1016/S1369-5266(03)00059-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing S., Zachgo S. (2007). Pollen lethality: a phenomenon in Arabidopsis RNA interference plants. Plant Physiol. 145, 330–333. 10.1104/pp.107.103127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue B., Hamamouch N., Li C., Huang G., Hussey R. S., Baum T. J., et al. (2013). The 8D05 parasitism gene of Meloidogyne incognita is required for successful infection of host roots. Phytopathology 103, 175–181. 10.1094/PHYTO-07-12-0173-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav B. C., Veluthambi K., Subramaniam K. (2006). Host generated double stranded RNA induces RNAi in plant parasitic nematodes and protects the host from infection. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 148, 219–222. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2006.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamanian M., Andersen E. C. (2016). Prospects and challenges of CRISPR/Cas genome editing for the study and control of neglected vector-borne nematode diseases. FEBS J. 283, 3204–3221. 10.1111/febs.13781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo K., Chen J., Lin B., Wang J., Sun F., Hu L., et al. (2017). A novel Meloidogyne enterolobii effector MeTCTP promotes parasitism by suppressing programmed cell death in host plants. Mol. Plant Pathol. 18, 45–54. 10.1111/mpp.12374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]