Abstract

Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP) is one of the most common diseases associated with pregnancy. In most cases, the skin lesions develop in the third trimester of primigravidas. There are no systemic alterations seen in PUPPP; however, most patients report severe pruritus. A 34-year-old woman presented 1 week postpartum with typical clinical features of PUPPP. The patient showed good response to intramuscular injection of autologous whole blood with no adverse effects to the patient or her baby. Presentation of PUPPP in the postpartum period is rare. Conservative management with topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines is commonly used to relieve pruritus. In severe cases, skin lesions and symptoms are controlled with a brief course of systemic corticosteroids. Investigation of new treatment options has been limited by patient concerns about the negative effects of medication on the fetus or breastfeeding. Intramuscular injection of autologous whole blood could be an alternative treatment option for PUPPP, especially for women who worry about the use of medications during pregnancy or breastfeeding.

Keywords: Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy, Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy

Introduction

Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP) is one of the most common diseases associated with pregnancy and is characterized by urticarial papules and plaques with pruritus on the abdomen, buttocks, and thighs [1]. In most cases, the skin lesions develop in the third trimester of primigravidas and disappear within 7–10 days after labor [1]. Presentation of PUPPP in the postpartum period is rare [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. Only few cases of PUPPP developing postpartum have been described in the literature (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of postpartum pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy cases

| No. | Age, years/ previous pregnancy | Period after labor | Distribution | Treatment | First author [Ref.], year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 23/P | 4 weeks | Abdomen, thighs, face | Topical corticosteroid | Kirkup [2], 2002 |

| 2 | 25/P | 10 days | Abdomen, buttock, all extremities | Oral antihistamine | Buccolo [3], 2005 |

| 3 | 34/P | 10 days | Abdomen, thighs | Topical corticosteroid, oral prednisolone, oral antihistamine | Byun [4], 2010 |

| 4 | 31/P | 4 weeks | Abdomen, buttock, breast, arms | Topical corticosteroid, oral prednisolone, oral antihistamine | Byun [4], 2010 |

| 5 | 20/P | 3 days | Abdomen, thighs, forearms, palmoplantar regions | Topical corticosteroid, oral prednisolone | Özcan [5], 2011 |

| 6 | 21/U | 12 days | Abdomen, buttock, thighs, lower lumbar region | Topical corticosteroid, oral prednisolone | Pritzier [8], 2012 |

| 7 | 26/P | 5 days | Abdomen, thighs | Topical corticosteroid, oral antihistamine | Pritzier [8], 2012 |

| 8 | 29/G | 2 days | Abdomen, thighs, legs | Topical corticosteroid, oral antihistamine | Ghazeeri [9], 2012 |

| 9 | 30/P | 7 days | All extremities | Topical corticosteroid and oral prednisolone, oral anti-histamine | Park [6], 2013 |

| 10 | 30/P | 1 day | Abdomen, buttock, thighs, legs, arms | Oral prednisolone, oral antihistamine | Dehdashti [7], 2015 |

| 11 | 34/P | 2 days | Abdomen, buttock, thighs, legs | Intramuscular injection of autologous whole blood | Present case |

P, primigravida; G, gravida; U, unknown.

There are no systemic alterations seen in PUPPP; however, most patients report severe pruritus [1]. Conservative management with topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines is commonly used to relieve pruritus [10]. In severe cases, skin lesions and symptoms are efficiently controlled with a brief course of systemic corticosteroids [11]. Recently Jeon et al. [12] reported 3 cases of PUPPP treated with intramuscular injection of autologous whole blood (AWB). Herein, we describe a case of PUPPP, which developed postpartum and was successfully treated with intramuscular injection of AWB.

Case Report

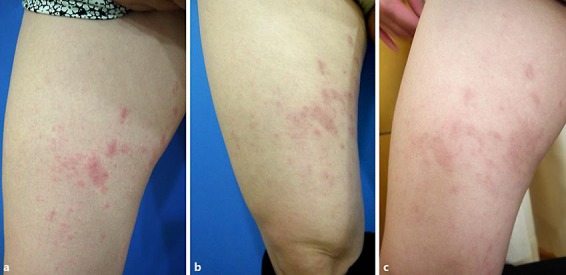

A 34-year-old woman, 1 week postpartum, presented to our dermatology clinic with an intensely pruritic generalized rash. Two days after delivery of her child, the patient developed an itchy rash on the abdomen. On discharge, she was instructed to follow up with the dermatology department if the rash did not resolve. After leaving the hospital, she reported that the eruption had progressively spread to the buttocks and legs and the itching seemed to be worse. The patient's prenatal course was uneventful. She gained 13 kg during pregnancy, with a prepregnancy weight of 72 kg. A healthy male neonate was delivered by caesarean section at 38 weeks' gestation without complication. The patient's medical history was unremarkable. She was currently not taking any medications, and she reported no known drug allergies. On physical examination, the patient was afebrile and her blood pressure was normal. Examination of the skin revealed erythematous papules and urticarial plaques involving the abdominal striae with periumbilical sparing. Similar lesions were noted on the legs and buttocks (Fig. 1a). The face, palms, and soles were uninvolved. No vesicles or pustules were noted. Based on the characteristic clinical presentation and disease course, she was diagnosed with PUPPP. She was informed of the safety profile and potential benefits of medications but remained reluctant to use medications during lactation, despite her severe symptoms. AWB injection was then considered for her treatment. Venous blood of 10 mL was drawn from the patient, followed by intramuscular injection of 5 mL of the blood on each side of her buttock. Seven days later, both subjective and objective improvements of symptoms were noticed and she received 1 more session of AWB injection (Fig. 1b). On follow-up after 12 days, all subjective symptoms had improved, leaving only postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (Fig. 1c). No complications such as infection, abscess formation, or hematoma were observed at the injection site.

Fig. 1.

Clinical manifestations and treatment response of the patient. a Before treatment, multiple, variably sized, coalescent, pruritic erythematous urticarial papules and plaques on the thigh are shown. b Seven days later, both subjective and objective improvements of symptoms were noticed. c After the second session, almost total relief of subjective symptoms and moderate postinflammatory hyperpigmentation were noted on follow-up 12 days later.

Discussion

During pregnancy, complex endocrinologic, immunologic, metabolic, and vascular changes influence the skin in various ways. PUPPP usually evolves in the third trimester and resolves rapidly postpartum and only rarely appears in the postpartum period [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. The lesions start in the abdominal striae with a periumbilical sparing [11]. The rash consists of very itchy small erythematous papules in the stretch marks which can coalesce to form larger urticarial abdominal plaques often surrounded by blanched halos. Occasionally, eczematous, polycyclic and target lesions or vesicles (but never bullae) eventually in an acral dyshidrosiform pattern can be seen [1, 10, 11]. Over days, the rash can spread over the thighs, buttocks, breasts, and arms with infrequent facial, hand, and foot lesions [1]. The diagnosis of PUPPP can be made clinically in typical cases based on the appearance of the rash. There are no specific laboratory abnormalities and only nonspecific histopathology with a perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with some edema and eosinophils in the dermis. Direct immunofluorescence studies of the skin are by definition negative [8, 10]. Skin biopsies are only performed to rule out other differential diagnoses such as pemphigoid gestationis, atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, drug eruptions, viral eruptions, and scabies [8]. Previous reports on PUPPP occurring postpartum showed that most patients were primigravidas with median onset of disease at 8.5 days (mean ± SD, 10.6 ± 9.9). The clinical features were similar to typical PUPPP with few cases showing unique distribution such as skin lesions limited to the extremities with abdominal sparing or lesions showing palmoplantar involvement. The patients were treated with a combination of topical corticosteroid, oral prednisolone, and oral antihistamine (Table 1).

The pathogenesis of PUPPP is not well understood and is likely multifactorial. Some theories have suggested that PUPPP may represent an immunologic response to circulating fetal antigens [13]. Other theories suggest that abdominal skin stretching, if drastic, can damage underlying connective tissue, resulting in the release of antigens that can trigger a reactive inflammatory response [14]. It also may be related to the degree of skin stretching during the third trimester and the abrupt decrease in the stretching of the skin that occurs with delivery [14]. Previous studies showed that hormonal influences related to pregnancy may also play a role in the development of this condition. Also, an association of PUPPP with male fetuses and cesarean deliveries has been reported [14, 15]. It is possible, as in this case, that along with the host factor and the circumstances of delivery, weight gain during the third trimester and drastic hormone fluctuations associated with labor and delivery may have caused an immune reaction leading to PUPPP postpartum.

Although the condition is harmless to the mother, the severe pruritus can be very annoying [8, 14]. Conservative treatment, such as mild to potent topical steroids, can be helpful in treating symptoms from the disease together with systemic antihistamines [10]. Investigation of new treatment options has been limited by patient concerns about the negative fetal effects of medication. AWB injection was often used for the treatment of chronic urticaria before the introduction of antihistamines and was also thought to have beneficial effects in treatment of atopic dermatitis [12]. The exact mechanism of action of AWB remains unclear, although it seems to affect immune function in experimental and clinical models. In animal models, AWB increased resistance to infection, enhanced antibody production to antigens, and activated cell-mediated immune defense [12]. Induced desensitization also seems to play an important role in the mechanism of AWB injection [12]. Thus, it is postulated that injection of AWB may have a positive effect on PUPPP by modulating maternal immune reactivity involved in disease development [12].

Conclusion

When a patient presents in the postpartum period with a pruritic eruption, PUPPP should be included in the differential diagnosis as to differentiate this entity from other dermatoses associated with pregnancy, as well as nonpregnancy-related conditions, in order to provide appropriate treatment and reassurance. Though the lesions may subside in due time, the pruritic symptoms of PUPPP may cause insomnia and stress which may have an effect on the breastfeeding mother. This case suggests that AWB injection could be an alternative treatment option for PUPPP, especially for women who worry about the use of medications during pregnancy or breastfeeding. Further studies should be performed to better understand the pathogenesis of PUPPP and mechanism of AWB injection.

Statement of Ethics

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for being included in this case report.

Disclosure Statement

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Matz H, Orion E, Wolf R. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy: polymorphic eruption of pregnancy (PUPPP) Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:105–108. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirkup ME, Dunnill MGS. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy developing in the puerperium. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:657–660. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2002.01099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buccolo LS, Viera AJ. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy presenting in the postpartum period: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2005;50:61–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byun J, Yang BH, Han SH, et al. Two cases of pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy in the postpartum. Korean J Dermatol. 2010;48:228–231. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Özcan D, Özçakmak B, Aydoğan FÇ. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy with palmoplantar involvement that developed after delivery. J Obstet Gynecol Res. 2011;37:1158–1161. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park SY, Kim JH, Lee WS. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy with unique distribution developing in postpartum period. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:506–508. doi: 10.5021/ad.2013.25.4.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dehdashti AL, Wikas SM. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy occurring postpartum. Cutis. 2015;95:344–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pritzier EC, Mikkelsen CS. Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy developing postpartum: 2 case reports. Dermatol Reports. 2012;4:e7. doi: 10.4081/dr.2012.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghazeeri G, Kibbi AG, Abbas O. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy: epidemiological, clinical, and histopathological study of 18 cases from Lebanon. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1047–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ambros-Rudolph CM. Dermatoses of pregnancy – clues to diagnosis, fetal risk and therapy. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:265–275. doi: 10.5021/ad.2011.23.3.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kroumpouzos G, Cohen LM. Dermatoses of pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:1–19. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.114595. quiz 19–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeon IK, On HR, Oh SH, Hann SK. Three cases of pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy (PUPPP) treated with intramuscular injection of autologous whole blood. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:797–800. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aractingi S, Berkane N, Bertheau P, et al. Fetal DNA in skin of polymorphic eruptions of pregnancy. Lancet. 1998;352:1898–1901. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen LM, Capeless EL, Krusinski PA, et al. Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy and its relationship to maternal-fetal weight gain and twin pregnancy. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:1534–1536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Regnier S, Fermand V, Levy P, Uzan S, Aractingi S. A case control study of polymorphic eruption of pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]