Abstract

Colon perforation is an uncommon but serious complication of colonoscopy. It may occur as either intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal perforation or in combination. The majority of colonic perforations are intraperitoneal, causing air and intracolonic contents to leak into the peritoneal space. Rarely, colonic perforation can be extraperitoneal, leading to the passage of air into the retroperitoneal space causing pneumoretroperitoneum, pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium, pneumothorax, and subcutaneous emphysema. A literature review revealed that 31 cases of extraperitoneal perforation exist, out of which 20 cases also reported concomitant intraperitoneal perforation. We report the case of a young female with a history of ulcerative colitis who developed combined intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal perforation after colonoscopy. We also report the duration of onset of symptoms, clinical features, imaging findings, site of leak, and treatment administered in previously reported cases of extraperitoneal colonic perforation.

Keywords: Extraperitoneal colonic perforation, Colonoscopy, Ulcerative colitis, Literature review, Symptoms

Introduction

Colonoscopy is a commonly performed procedure for the diagnosis and treatment of a wide range of conditions and symptoms and for the screening and surveillance of colorectal neoplasia. Colonic perforation occurs in 0.03–0.8% of colonoscopies [1, 2] and is the most feared complication with a mortality rate as high as 25% [1]. It may result from mechanical forces against the bowel wall, barotrauma, or as a direct result of therapeutic procedures. Colon perforation may occur as either intraperitoneal or extraperitoneal perforation or in combination. The majority of colonic perforations are intraperitoneal, causing air and intracolonic contents to leak into the peritoneal space. This manifests as persistent abdominal pain and abdominal distention, later progressing to peritonitis. A plain radiograph may demonstrate free air under the diaphragm.

Rarely, colonic perforation can be extraperitoneal, leading to the passage of air into the retroperitoneal space, which then diffuses along the fascial planes and large vessels causing pneumoretroperitoneum, pneumomediastinum, pneumopericardium, pneumothorax, and subcutaneous emphysema. Such patients can have atypical presentation, including subcutaneous crepitus, neck swelling, chest pain, and shortness of breath after colonoscopy. The combination of intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal perforation has also been reported. A literature review revealed that 31 cases of extraperitoneal perforation exist, out of which 20 cases also reported concomitant intraperitoneal perforation. We report the case of a young female with a history of ulcerative colitis (UC) who developed combined intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal perforation after colonoscopy. We also report the duration of onset of symptoms, clinical features, imaging findings, site of leak, and treatment administered in previously reported cases of extraperitoneal colonic perforation.

Case Presentation

A 41-year-old Caucasian female with a history of UC on vedolizumab presented with complaints of 7–10 daily episodes of watery diarrhea for 2 days associated with crampy, intermittent lower abdominal pain and subjective fever without any chills. She denied any recent hospitalization, antibiotic exposure, travel, or sick contact. She appeared cachectic with a body mass index of 18.7 and reported a 15-pound weight loss over the last 2 months. On examination, she had a temperature of 100.4° F, a blood pressure of 110/78 mm Hg, and a heart rate of 105/min, and abdominal exam revealed hyperactive bowel sounds, diffuse tenderness without guarding, rigidity, or rebound tenderness. Notable lab abnormalities included erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 43 mm/h, white blood cell count of 12.6 × 109/L, hemoglobin of 10.8 g/dL, and albumin of 2.6 g/dL. Stool Clostridium difficile PCR and ova/parasites screen were negative. Computerized tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen demonstrated diffuse colitis with a transverse colon diameter of 2.4 cm and right-sided pyelonephritis. Given her clinical features and evidence of colitis on imaging, she was thought to be having an exacerbation of UC and was started on intravenous (IV) normal saline, IV methylprednisolone, and IV ciprofloxacin/metronidazole for pyelonephritis. She reported considerable improvement in her symptoms, with the resolution of diarrhea and abdominal pain over the next few days. Her quality of life was poor due to multiple exacerbations of UC from medication noncompliance; therefore, surgical intervention was planned. Colonoscopy was performed on day 7 of hospitalization. The colonoscope was passed through the anus under direct visualization and was advanced with ease to the transverse colon. The scope was withdrawn, and the mucosa was carefully examined, which revealed mild colitis in the distal transverse colon, while the descending colon and the sigmoid colon showed severe colonic inflammation. The mucosa appeared cobblestoned, edematous, erythematous, and ulcerated. Biopsies were obtained from the sigmoid colon and descending colon. The quality of the preparation was good, and the patient tolerated the procedure well. Histology was consistent with UC.

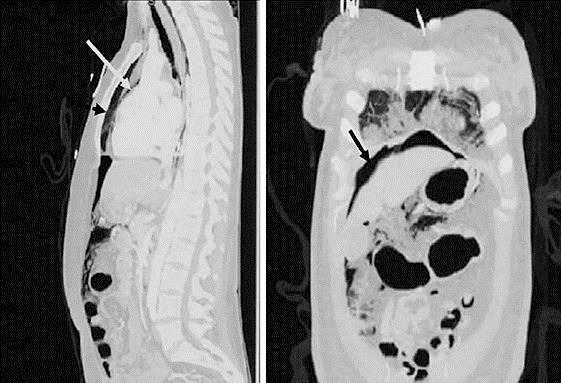

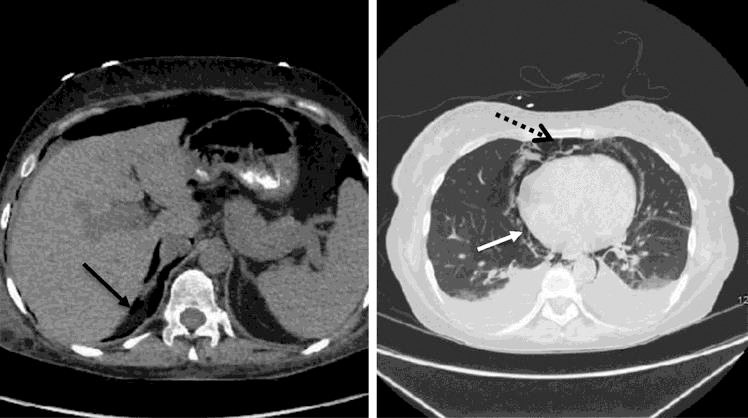

The following day, she was noted to have subcutaneous emphysema of the chest wall. CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed large pneumoperitoneum, pneumomediastinum, and pneumopericardium with air tracking all the way up into the neck (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). The patient remained asymptomatic. She had an exploratory laparotomy, was found to have transverse colon perforation, and underwent subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy. The patient had an uncomplicated postoperative course and was discharged home in stable condition.

Fig. 1.

Computerized tomography of the chest and abdomen showing pneumomediastinum (broken arrow), pneumopericardium (white arrow), and pneumoperitoneum (black arrow).

Fig. 2.

Computerized tomography of the abdomen (left) and chest showing pneumoperitoneum (black arrow), pneumomediastinum (broken arrow), and pneumopericardium (white arrow).

Discussion

The perforation rate in diagnostic colonoscopy ranges from 0.03 to 0.8%, and in therapeutic colonoscopy it ranges from 0.15 to 3% [1, 2]. In the majority of cases, the perforation after a colonoscopy is intraperitoneal, and only a few cases reporting extraperitoneal perforation exist in the literature (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reported cases of extraperitoneal and combined colonic perforation after diagnostic and therapeutic colonoscopy

| Pts | First author, year | Procedure type | Time of onset of symptoms | Clinical features | Imaging findings |

Site of perforation | Management | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP* | PT* | PM* | |||||||

| 1 | Our case | Colonoscopy with sigmoid biopsy, history of UC | 24 h | Subcutaneous emphysema | Yes | No | Yes | Transverse colon | Laparotomy and subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy |

| Pneumopericardium | |||||||||

| 2 | Yang, 2016 | Colonoscopy with resection of rectal adenoma | Immediate | SOB, subcutaneous emphysema | Yes | Yes | Yes | Rectum | Conservative |

| 3 | Patel, 2015 | Flexible sigmoidoscopy with SEMS deployment | 1 day | Asymptomatic | No | Yes | Yes | Sigmoid | Conservative |

| 4 | Palomeque, 2015 | Colonoscopy | Immediate | Abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting | Yes | Yes | No | Rectosigmoid | Primary closure of perforation |

| 5 | Mihatov, 2015 | Colonoscopy with Biopsy for CD | 9 days | Sudden onset chest pain and dyspnea | No | No | Yes | Unknown | laparoscopic subtotal colectomy |

| 6 | Ahmed, 2014 | Colonoscopy with biopsies for CD | Immediate | Scrotal swelling, abdominal pain | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Subtotal colectomy |

| 7 | Pourmand, 2013 | Colonoscopy | Immediate | SOB, abdominal pain, chest pain | Yes | Yes | No | Unknown | Conservative |

| 8 | Denadai, 2013 | Colonoscopy with rectal polypectomy | 3 days | Neck swelling, malaise, neck crepitus | No | No | Yes | Rectum | Conservative |

| 9 | Loughlin, 2012 | Colonoscopy with biopsy for UC | 6 h | Neck pain and crepitus, odynophagia | No | No | Yes | Unknown | Conservative |

| 10 | Albert, 2012 | Colonoscopy | Immediate | Asymptomatic | Yes | Yes | Yes | Sigmoid | Operative |

| 11 | Marariu, 2012 | Colonoscopy | Several hours | Chest pain, emphysema of neck, face, chest | Yes | No | Yes | Unknown | Conservative |

| 12 | Evangelos, 2012 | Colonoscopy | Immediate | Abdominal pain, neck, face and left orbit swelling | Yes | No | Yes | Sigmoid | Laparotomy with sigmoid resection |

| 13 | Kwang, 2011 | Colonoscopy | 2 days | Abdominal pain, neck swelling | No | No | Yes | Rectum | Conservative |

| 14 | Chan, 2010 | Colonoscopic balloon dilatation | Immediate | Oxygen desaturation, neck swelling, cyanosis | Yes | Yes | Yes | Sigmoid | Conservative |

| 15 | Cappello, 2010 | Colonoscopy, history of UC | 1 h | Face and neck swelling, abdominal pain, fever | Yes | No | Yes | Cecum | Laparotomy with right hemicolectomy |

| 16 | Kipple, 2010 | Colonoscopy with sigmoid polypectomy | 8 h | Abdominal pain, dyspnea, neck swelling | Yes | Yes | Yes | Sigmoid | Operative resection of perforated segment |

| 17 | Fazeli, 2009 | Colonoscopy with random biopsies | 15 min | Respiratory distress and swelling of face, neck | No | No | Yes | Sigmoid | Laparotomy and resection of perforated segment |

| 18 | Konstantinos, 2008 | Colonoscopy with rectal polypectomy | 24 h | Hoarseness, neck swelling | No | No | Yes | Rectum | Conservative |

| 19 | Marwan, 2007 | Colonoscopy | Immediate | Emphysema of face, chest, abdomen | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Conservative |

| 20 | Nark-Soon, 2007 | Colonoscopy | Not specified | Abdominal pain, neck swelling, dyspnea | Yes | No | Yes | Sigmoid | Colonoscopic clip placement |

| 21 | Zeno, 2006 | Colonoscopy | Immediate | Abdominal pain, vomiting | Yes | Yes | No | Sigmoid | Laparotomy with hemicolectomy |

| 22 | Shallaly, 2005 | Sigmoidoscopy with rectal biopsy | 2 h | Neck swelling, dysphagia, voice change | No | No | Yes | Rectum | Conservative |

| 23 | Mastrovich, 2004 | Colonoscopy with cecal polypectomy | Immediate | Facial fullness, SOB | Yes | No | Yes | Unknown | Conservative |

| Pneumopericardium | |||||||||

| 24 | Hirofumi, 2002 | Colonoscopy with rectal tumor biopsy | 2 h | Facial edema, emphysema in neck | No | No | Yes | Sigmoid | Laparotomy and sigmoid colon resection |

| Pneumopericardium | |||||||||

| 25 | Webb, 1998 | Colonoscopy | 30 min | Neck, facial, periorbital edema, SOB | No | Yes | Yes | Unknown | Conservative |

| 26 | William, 1996 | Colonoscopy with sigmoid polypectomy | 1 h | Facial edema, chest pain, emphysema in neck, chest | No | Yes | Yes | Sigmoid | Conservative |

| 27 | Ho, 1996 | Colonoscopy with cecal polypectomy | Immediate | Substernal chest pain | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cecum | Laparotomy with right hemicolectomy |

| 28 | Fitzgerald, 1992 | Colonoscopy with polypectomy, history of UC | 9 h | Neck swelling, voice change, abdominal discomfort | Yes | No | Yes | Transverse colon | Laparotomy with primary closure |

| Pneumopericardium | |||||||||

| 29 | Bakker, 1991 | Colonoscopy with rectal polypectomy (prior Ileo-transversotomy) | 2 h | Abdominal pain | Yes | No | Yes | Ileocolostomy site | Laparotomy with primary closure |

| Pneumopericardium | |||||||||

| 30 | McCollister, 1990 | Colonoscopy with cecal polypectomy | 7 h | Abdominal pain, neck swelling, SOB | Yes | No | Yes | Cecum | Conservative |

| 31 | Foley, 1982 | Sigmoidoscopy | 30 min | Neck pain and swelling, retrosternal pain | No | No | Yes | Sigmoid | Conservative |

| 32 | Amshel, 1982 | Colonoscopy with sigmoid polypectomy | Few hours | Asymptomatic, low grade fever | Yes | No | Yes | Sigmoid | Conservative |

PP, pneumoperitoneum; PT, pneumothorax; PM, pneumomediastinum; UC, ulcerative colitis; CD, Crohn disease; SEMS, self-expanding metallic stent; SOB, shortness of breath.

Mechanism of Extraperitoneal Air Leak

In extraperitoneal perforation, extraluminal air may reach the different body compartments in neck and chest. Maunder et al. [3] described the route of extraperitoneal gas. The soft-tissue compartment of the neck, thorax, and abdomen contains 4 regions: (1) the subcutaneous tissue, (2) prevertebral tissue, (3) visceral space, and (4) previsceral space. These spaces are connected along the neck, chest, and abdomen. Air leaked into one of these spaces may pass into others along fascial planes and large vessels, eventually reaching the neck and pericardial, mediastinal, and pleural space.

Procedure Characteristics

Iatrogenic colonoscopic perforations can result from diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Diagnostic perforation is the result of mechanical disruption of the colonic wall induced directly by the tip of the endoscope or by considerable stretching of the bowel, especially when loops are formed or the endoscope is advanced by the slide-by technique. Therapeutic perforations can be induced by any intervention involving dilation or electrocoagulation, including treatment of arteriovenous malformations and, most commonly, polypectomy [4, 5]. Out of 32 cases of extraperitoneal perforation (Table 1), 19 perforations (59%) occurred after diagnostic colonoscopy, and biopsies were obtained in 7 of them. Thirteen perforations (40%) were the result of colonoscopy involving some form of intervention, including polypectomy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of findings in isolated extraperitoneal and combined intra- and extraperitoneal perforations (n = 32 cases)

| Extraperitoneal (n = 12), n (%) | Combined (n = 20), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of procedure | ||

| Diagnostic only | 3 (25) | 9 (45) |

| Diagnostic with biopsy | 5 (42) | 2 (10) |

| Therapeutic (including polypectomy) | 4 (33) | 9 (45) |

| Onset of symptoms | ||

| Immediate | 4 (33) | 12 (60) |

| >1 h and <24 h | 3 (25) | 6 (30) |

| ≥24 h | 5 (42) | 1 (10)a |

| Clinical features | ||

| Neck swelling | 10 (83) | 11 (55) |

| Dyspnea | 3 (25) | 5 (25) |

| Chest pain | 3 (25) | 3 (15) |

| Abdominal pain | 1 (8) | 10 (50) |

| Asymptomatic | 1 (8) | 2 (10) |

| Imaging | ||

| Pneumoperitoneum | 0 (0) | 20 (100) |

| Pneumothorax | 3 (25) | 10 (50) |

| Pneumomediastinum | 12 (100) | 17 (85) |

| Pneumopericardium | 1 (8) | 4 (20) |

| Site of perforation | ||

| Rectosigmoid | 9 (75) | 9 (45) |

| Cecum | 0 (0) | 3 (15) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 3 (15) |

| Unknown | 3 (25) | 5 (25) |

| Management | ||

| Conservative | 9 (75) | 8 (40) |

| Surgical | 3 (25) | 12 (60) |

One case with unknown duration of onset of symptoms excluded.

Onset of Symptoms

Perforations can be detected immediately during the procedure by visualizing the perforation site, or the patient may become symptomatic after a few hours to days. On reviewing 32 cases of extraperitoneal perforations (Table 1), we found out that in 16 cases (52%), the perforation was detected within 1 h, in 9 cases (29%) within 1–24 h, and in 6 cases (19%) >24 h after the procedure. Development of subcutaneous emphysema presents with neck or facial swelling (which is readily visible); this may be the reason for earlier detection of extraperitoneal perforations (Table 2).

Symptoms of Extraperitoneal Perforation

After a regular colonoscopy, many patients experience some crampy abdominal pain because of retained air in the bowel. Intraperitoneal perforation can cause peritoneal irritation with rebound tenderness, rigidity of the abdomen, accompanied by fever, leukocytosis, and tachycardia. The most common presenting clinical feature of extraperitoneal colonic perforation was subcutaneous emphysema of the neck, face, or upper chest seen in 21 patients (65%), followed by abdominal pain seen in 11 patients (34%) and dyspnea in 8 patients (25%). Close to 10% of patients remained asymptomatic (Table 2). In cases of isolated extraperitoneal perforation, only 1 patient (8%) presented with abdominal pain.

Imaging

Of the 32 cases presented in Table 1, 29 patients (90%) had pneumomediastinum, 13 patients (40%) had pneumothorax, and 5 patients (15%) had pneumopericardium on chest X-ray or CT scan. Plain radiographs are usually diagnostic of perforations, but CT scan is recommended if findings are not definitive or if the presence of free air cannot be ruled out by radiographs alone.

Site of Perforation

The most common site of extraperitoneal perforation was rectosigmoid in 18 patients (56%) followed by the cecum in 3 cases (9%). Panteris et al. [6] also reported that the most frequent site of all types of perforation is the sigmoid followed by the cecum. The sigmoid colon is the most common site of perforation (1) as shearing forces applied during endoscope insertion cause trauma to the sigmoid colon and (2) as it is a common location of diverticula and polyps, both of which make mechanical or thermal injury more likely in this region. The cecum is well known to have a thinner muscular layer and a larger diameter than the rest of the bowel, both of which render it susceptible to barotraumas. Our patient had UC with friable colonic mucosa which predisposes to perforation.

Treatment and Prognosis

The decision whether surgery or nonoperative treatment should be employed will depend on the type of injury, the quality of bowel preparation, the underlying colonic pathology, and the clinical stability of the patient [7, 8]. A selected number of patients can be treated conservatively with bowel rest, IV antibiotics, and close observation [9, 10, 11]. Surgical options include primary repair of the perforated bowel segment or segmental resection [12]. Surgical intervention is more likely to be successful if the perforation is diagnosed earlier than 24 h after perforation; hence, early recognition and treatment are imperative [13, 14]. In cases of extraperitoneal perforation, 17 patients (53%) were treated conservatively, while 15 patients (47%) needed operative management. Twelve patients (60%) with combined intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal perforation needed surgical intervention (Table 2), while only 3 patients (25%) with isolated extraperitoneal perforation needed surgery. All patients recovered well with no reported mortality.

In summary, we described a case of combined intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal perforation after diagnostic colonoscopy in a patient with UC. A literature review of cases reporting extraperitoneal perforation revealed that the majority of such perforations were detected immediately after the procedure. Most patients presented with subcutaneous emphysema of the neck, face, or upper chest followed by abdominal pain. On imaging, pneumomediastinum was the most common finding, and the most common site of extraperitoneal perforation was the rectosigmoid area. Conservative treatment was successful in the majority of cases.

Therefore, physicians should be cognizant of the possibility of extraperitoneal perforation whenever a patient presents with subcutaneous emphysema, chest pain, and/or shortness of breath after colonoscopy. Abdominal pain is not seen in a majority of patients; therefore, an absence of abdominal pain and abdominal tenderness should not be a reason to exclude colonic perforation.

Statement of Ethics

The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Luning TH, Keemers-Gels ME, Barendregt WB, et al. Colonoscopic perforations: a review of 30,366 patients. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:994–997. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wullstein C, Koppen M, Gross E. Laparoscopic treatment of colonic perforations related to colonoscopy. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:484–487. doi: 10.1007/s004649901018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maunder RJ, Pierson DJ, Hudson LD. Subcutaneous and mediastinal emphysema, pathophysiology diagnosis and management. Arch Intern Med. 1984;144:1447–1453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fatima H, Rex DK. Minimizing endoscopic complications: colonoscopic polypectomy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2007;17:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2006.10.001. viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waye JD, Kahn O, Auerbach ME. Complications of colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1996;6:343–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panteris V, Haringsma J, Kuipers EJ. Colonoscopy perforation rate, mechanisms and outcome: from diagnostic to therapeutic colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2009;41:941–951. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1215179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damore LJ, Rantis PC, Vernava AM, et al. Colonoscopic perforations. Etiology, diagnosis, and management. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1308–1314. doi: 10.1007/BF02055129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson ML, Pasha TM, Leighton JA. Endoscopic perforation of the colon: lessons from a 10-year study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3418–3422. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weber DJ, Rodney WM, Warren J. Management of suspected perforation following colonoscopy: a case report. Fam Pract. 1993;36:567–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waye JD, Kahn O, Auerbach ME. Complications of colonoscopy and flexible sigmoidoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1996;6:343–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall C, Dorricott NJ, Donovan IA, Neoptolemos JP. Colon perforation during colonoscopy: operative versus non-operative management. Br J Surg. 1991;78:542–544. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen AJ, Tessier DJ, Ander son ML, et al. Laparoscopic repair of colonoscopic perforations: indications and guidelines. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:655–659. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iqbal CW, Chun YS, Farley DR. Colonoscopic perforations: a retrospective review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:1229–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teoh AY, Poon CM, Lee JF, et al. Outcomes and predictors of mortality and stoma formation in operative management of colonoscopic perforations: a multicenter review. Arch Surg. 2009;144:9–13. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2008.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]