Abstract

According to current guidelines, follow-up of patients with colorectal cancer is ended after five years. Also, chest X-ray is not part of standard investigation during follow-up. We describe a case of a 74-year-old patient, more than ten years after a sigmoid resection because of carcinoma of the sigmoid. No recurrence was detected during intensive follow-up. However, ten years after resection of the sigmoid adenocarcinoma, complaints of coughing induced further examination with as result the detection of a solitary metastasis in the left lung of the patient. Within half-a-year after metastasectomy of the lung metastasis, she presented herself with thoracic pain and dyspnea resulting in discovering diffuse metastasis on pulmonary, pleural, costal and muscular level. Five year follow-up of colorectal carcinoma without chest X-ray can be questioned to be efficient. The growing knowledge of tumor biology might in future adjust the duration and frequency of diagnostic follow-up to prevent (late) recurrence in patients with colorectal carcinoma.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Metastasis, Tumor biology, Tumor dormancy, Follow-up

Core tip: This case report presents a case of a woman with pulmonary metastases 10 years after a sigmoid resection. No recurrence of the primary intestinal tumor was detected during follow-up. Upcoming knowledge on tumor behavior based on its biology might give new insights in late-onset metastases. Therefore, follow-up protocols and current therapy guidelines might have to be re-evaluated.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal carcinoma (CRC) is the most common type of gastrointestinal cancer. The current screening methods enable early detection, for example adenomatous polyps, to prevent the development of invasive carcinoma[1]. Etiology of CRC comprises genetic involvement, molecular events, environmental factors and inflammatory conditions[2]. CRC usually develops over a period of 10-15 years[3], most often affecting people aged over 50[4]. After a curative resection, prognosis of CRC is worse in poorly differentiated, mucinous carcinomas with large invasion depth and in the presence of lymph node metastases[5]. Follow-up of patients with CRC according to the national guidelines consists of echography or computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen, colonoscopy and determination of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) until five years after surgical resection[6].

CRC can spread by lymphatic and hematogenous dissemination, as well as by contiguous and transperitoneal routes. Metastasis, at initially diagnosis present in 20% of all patients, is the main cause of mortality in patients with CRC[7,8]. When cancer spreads to one single organ, the malignancy presents itself with a specific biological profile and clinical characteristics. The site of the metastatic disease influences the prognosis and the possibilities for treatment. Organs most often affected by CRC are the liver and the lungs[9]. For pulmonary lesions, the criteria for resectability of the metastatic lesion comprise; control of the primary tumor, possible complete resection and adequate pulmonary reserve to tolerate the planned resection[10].

CASE REPORT

Ten years ago, a 63-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with changes in bowel habits. At that time, she had no medical history of abdominal complaints or surgical operations. Her father was familiar with lung carcinoma, her mother and both of her sisters suffered from breast carcinoma.

A colonoscopy reveals a sigmoid colon stricture with unknown length due to the impossibility of endoscopically passing the stricture. Biopsy of the sigmoid shows a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. Computed tomography and echography of the liver, spleen and of the pelvic, cardio-thoracic, para-aortic and paracaval region show no lesions suspected for malignancy. An uncomplicated surgical resection of the sigmoid took place. The tumor, with a maximum diameter of five centimeters, including five surrounding lymph nodes and infiltrated fat tissue were removed in totality. No lymph node metastases were detected.

One year after the surgical resection, biopsy of a polyp of the ascending colon showed a tubular adenoma with low grade dysplasia. During further follow up of this patients no malignancies or recurrent lesions were disclosed. The CEA was tested every three months with a maximum value of 2.2 mcg/L. The intensive follow-up period was completed five years after sigmoid resection.

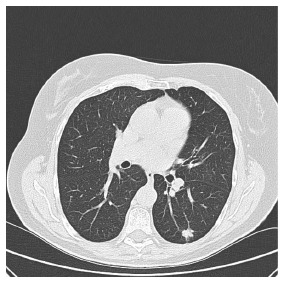

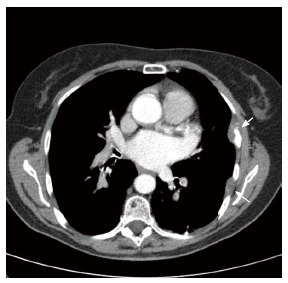

Ten years after resection of the adenocarcinoma located in the sigmoid without recurrent carcinoma’s during follow up, our patient presented herself with persistent coughing. Imaging of the thorax shows a lesion of 1.5 centimeters located in the inferior lobe of the left lung (Figure 1). Biopsy reveals an adenocarcinoma with positive CDX-2 staining, corresponding with intestinal origin of the cells. The pulmonary tumor was removed by video assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), presumably in totality. Colonoscopy shows no metachronous neoplasia. Within half a year, she was admitted to our emergency department with complaints of pain on the left side of her chest resulting in dyspnea, the pain was coherent with breathing movement and pain radiation towards her spine. CT-thorax shows extensive pleural, costal and muscular metastases (Figure 2). To reduce pain, palliative chemotherapy and additional radiotherapy were started.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography of the pulmonary lesion.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography of the pleural metastasis (indicated with arrows).

DISCUSSION

Early detection of relapse or metastatic disease can be effectuated by intensive follow up during five years as recorded in the directive of Oncoline[6]. This follow-up comprises echography and optional CT-abdomen twice a year during 1-2 years, followed by once a year up to 5 years after the surgical resection. CEA should be determined every 3-6 mo during 3 years, followed by every 6 mo until 5 years after treatment. Colonoscopy is performed three, six and twelve months after surgical resection. Based on the number, localization and size of the lesions, repetition of colonoscopy is indicated after 3 or 5 years[6].

However, several clinical and experimental observations suggest that metastases can develop even in the absence of a detectable primary tumor. Both large and small tumors have the capability to metastasize[11,12]. Dissemination of tumor cells can occur in pre-invasive stages of tumor progression resulting in the development of early dormant disseminated tumor cells (DTCs). Early DTCs can remain dormant for a long period with manifestation of metastatic growth as result[13,14]. Metastases may thus be initiated by and evolve from dormant DTCs, rather than established primary tumors. These DTCs can generate metastases with different characteristics from those of the primary tumor. The discriminating characteristics may explain the lack of success treating metastases with therapies based on primary tumor characteristics[14]. Clinical evidence supports that the vast majority of early DTCs seem to be dormant[13].

In conclusion, five year follow-up of colorectal carcinoma without chest X-ray can be questioned to be efficient with the upcoming knowledge of early DTC’s. Adjustment of the duration and frequency of diagnostic follow-up and adjustment of treatment might be effective for early detection of metastatic disease and prevention of late recurrence in patients with colorectal carcinoma.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank Simons P, MD, PhD for providing the CT-scan figures.

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

A 63-year-old woman presented with a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the sigmoid as primary tumor. No recurrence of the primary intestinal tumor was detected during follow-up. Ten years after resection of the primary tumor, computed tomography reveals a pulmonary metastasis in the left lung of the patient.

Clinical diagnosis

Persistent cough.

Differential diagnosis

The most common causes of chronic cough are postnasal drip, asthma, and acid reflux from the stomach. Less common causes include infections, medications, and lung diseases (e.g., primary/secondary malignancy).

Laboratory diagnosis

No raised CRP or ESR. Normal leucocyte count. Carcinoembryonic antigen 1.7 mcg/L.

Imaging diagnosis

Computed tomography (CT) shows a lesion of 1.5 centimeters located in the inferior lobe of the left lung.

Pathological diagnosis

Pulmonary metastasis of intestinal origin; a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma.

Treatment

Metastasectomy by video assisted thoracic surgery.

Related reports

Follow-up of colorectal carcinoma consists of echography, optional CT-abdomen, CEA determination and colonoscopy. Without recurrence of the tumor within five years after primary resection, intensive follow-up is ended. However, several clinical and experimental observations suggest that metastases can develop even in the absence of a detectable primary tumor, based on the principle of dormant disseminated tumor cells.

Term explanation

Late onset pulmonary metastases more than ten years after primary colorectal cancer, without recurrence of the primary tumor, is very rare.

Experiences and lessons

Most recent guidelines recommend follow-up until five years after treatment of colorectal cancer. A pulmonary mass on imaging of the thorax, even more than 10 years after curative resection, is suspicious for metastatic disease. In general, more insights in the behavior of cancer (tumor biology) might change follow-up regimens in future.

Peer-review

The authors presented a case of a woman with pulmonary metastases 10 years after a sigmoid resection. This is clinically important and the paper is well written.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: Approval from the Local Ethical Committee for this study was granted.

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Conflict-of-interest statement: Both authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: The Netherlands

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: October 27, 2016

First decision: December 1, 2016

Article in press: March 13, 2017

P- Reviewer: Akiho H, Deng CX, Peinado MA S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Desch CE, Benson AB, Somerfield MR, Flynn PJ, Krause C, Loprinzi CL, Minsky BD, Pfister DG, Virgo KS, Petrelli NJ. Colorectal cancer surveillance: 2005 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8512–8519. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dragovich T, Tsikitis VL, Talavera F, Espat NJ, Schulman P. Colon Cancer (Medscape 2016) Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/277496-overview.

- 3.Kelloff GJ, Schilsky RL, Alberts DS, Day RW, Guyton KZ, Pearce HL, Peck JC, Phillips R, Sigman CC. Colorectal adenomas: a prototype for the use of surrogate end points in the development of cancer prevention drugs. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3908–3918. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z,Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds) SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, United States. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2012/

- 5.Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, Professional Edition. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Comprehensive Cancer Centre The Netherlands. Dutch guideline “colorectal carcinoma”. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Cutsem E, Oliveira J. Advanced colorectal cancer: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2009;20 Suppl 4:61–63. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vatandoust S, Price TJ, Karapetis CS. Colorectal cancer: Metastases to a single organ. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:11767–11776. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i41.11767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warwick R, Page R. Resection of pulmonary metastases from colorectal carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33 Suppl 2:S59–S63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van de Wouw AJ, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Coebergh JW, Hillen HF. Epidemiology of unknown primary tumours; incidence and population-based survival of 1285 patients in Southeast Netherlands, 1984-1992. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:409–413. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00378-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engel J, Eckel R, Kerr J, Schmidt M, Fürstenberger G, Richter R, Sauer H, Senn HJ, Hölzel D. The process of metastasisation for breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1794–1806. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(03)00422-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hüsemann Y, Geigl JB, Schubert F, Musiani P, Meyer M, Burghart E, Forni G, Eils R, Fehm T, Riethmüller G, et al. Systemic spread is an early step in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sosa MS, Bragado P, Aguirre-Ghiso JA. Mechanisms of disseminated cancer cell dormancy: an awakening field. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:611–622. doi: 10.1038/nrc3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]