Abstract

Objectives: Efforts to treat Escherichia coli infections are increasingly being compromised by the rapid, global spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Whilst AMR in E. coli has been extensively investigated in resource-rich settings, in sub-Saharan Africa molecular patterns of AMR are not well described. In this study, we have begun to explore the population structure and molecular determinants of AMR amongst E. coli isolates from Malawi.

Methods: Ninety-four E. coli isolates from patients admitted to Queen’s Hospital, Malawi, were whole-genome sequenced. The isolates were selected on the basis of diversity of phenotypic resistance profiles and clinical source of isolation (blood, CSF and rectal swab). Sequence data were analysed using comparative genomics and phylogenetics.

Results: Our results revealed the presence of five clades, which were strongly associated with E. coli phylogroups A, B1, B2, D and F. We identified 43 multilocus STs, of which ST131 (14.9%) and ST12 (9.6%) were the most common. We identified 25 AMR genes. The most common ESBL gene was blaCTX-M-15 and it was present in all five phylogroups and 11 STs, and most commonly detected in ST391 (4/4 isolates), ST648 (3/3 isolates) and ST131 [3/14 (21.4%) isolates].

Conclusions: This study has revealed a high diversity of lineages associated with AMR, including ESBL and fluoroquinolone resistance, in Malawi. The data highlight the value of longitudinal bacteraemia surveillance coupled with detailed molecular epidemiology in all settings, including low-income settings, in describing the global epidemiology of ESBL resistance.

Introduction

In Africa, Escherichia coli is the second most common Gram-negative cause of community-acquired bloodstream infection, accounting for 7.3% of all confirmed bloodstream infection isolates,1 and is also one of the leading causes of diarrhoeal disease, which is responsible for >10.0% of all deaths globally in children under 5 years old, and >11.0% in Africa.2,3E. coli is rapidly becoming resistant to first-line and last-resort antimicrobial agents, including cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and, in some settings, carbapenems,4–7 resulting in infections that are difficult or impossible to treat depending on local availability of antimicrobials. The spread of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has often been attributed to selective pressure resulting from increased use of antimicrobial agents.8 In most developing countries, the high burden of invasive bacterial infection, the high prevalence of immune-suppressive conditions (e.g. malnutrition and HIV) and lack of diagnostic microbiology facilities necessitates the widespread use of broad-spectrum antimicrobials. In Malawi, high levels of cephalosporin and fluoroquinolone resistance in E. coli strains have been reported following extensive use of ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin.9 Cephalosporin- and fluoroquinolone-resistant E. coli have also been reported from a number of other countries in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA).10–12

The main mechanism of cephalosporin resistance is drug inactivation, which is mediated by hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring of the antimicrobial agent by ESBL enzymes. CTX-M derivatives, and in particular CTX-M-15, are now the dominant and most widely disseminated ESBL type found amongst E. coli isolates.7 Furthermore, despite the high genetic diversity associated with the E. coli species,13 ESBLs, especially of the CTX-M type, are strongly associated with specific clonal E. coli lineages.8 In the case of CTX-M-15, it is predominantly associated with a globally disseminated ST131 clone.8,14 The ESBL-producing lineages are also associated with fluoroquinolone resistance15 despite being mediated by different mechanisms. Unlike cephalosporin resistance, fluoroquinolone resistance is mainly conferred by chromosomal mutations in the quinolone-binding target genes, such as the subunits of the gyrase genes gyrA or gyrB and topoisomerase IV genes parC or parE.16 Plasmid-mediated genes such as qnr, qep and aac(6ʹ)-Ib-cr have also been shown to confer low-level fluoroquinolone resistance.16

WGS has emerged as an essential tool in understanding the emergence and spread of resistant strains and therefore informing strategies to combat AMR. Whilst the emergence of ESBL and fluoroquinolone resistance in SSA is a major public health concern, there are limited studies to provide genomic insight into the molecular patterns underlying the spread of ESBL and fluoroquinolone resistance in the region. To our knowledge, we carried out this first E. coli WGS study in Malawi to provide a baseline for understanding the genetic population structure of clinical isolates of E. coli and identify E. coli lineages associated with ESBL resistance in this setting.

Materials and methods

Ethics

The Malawi-Liverpool-Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Programme (MLW) routine culture surveillance, under which the isolates were obtained, was approved by the College of Medicine Research Ethics Committee (COMREC) of the University of Malawi, approval number P.08/14/1614.

Study setting and sample collection

We used samples collected as part of routine bacteraemia and meningitis surveillance undertaken at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH), Blantyre, Malawi, and archived at MLW. QECH is the largest government hospital in Malawi, serving Blantyre (population ∼1.3 million) and the surrounding districts. Adults had blood sampled for culture when admitted to QECH with fever (axillary temperature >37.5°C) or clinical evidence of sepsis.17 CSF samples were taken from the adult patients where there was clinical suspicion of meningitis.18 Blood or CSF samples were taken from children with febrile illness, but who were malaria slide negative and had no obvious focus of infection, or who were severely ill with sepsis or meningitis, and patients who failed initial malaria treatment and remained febrile.19 Antimicrobial susceptibility tests were performed by the disc diffusion method using methods and breakpoints outlined by BSAC (www.bsac.org.uk). Isolates were tested against six commonly used antimicrobial agents, namely ampicillin, co-trimoxazole, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, cefpodoxime and ciprofloxacin. Isolates were stored on beads at −80°C.

Isolate selection and DNA extraction

Sixty blood culture and 26 CSF E. coli isolates were selected from the MLW archives on the basis of diversity of phenotypic resistance profiles and clinical source of isolation. Isolates originated from paediatric (<16 years old) and adult (≥16 years old) patients from the period 1996–2014. Eight rectal swab isolates, all from 2009, were also included. Whole-genome DNA extraction for selected isolates was done at MLW laboratories using the Qiagen Universal Biorobot (Limburg, the Netherlands), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

WGS, de novo assembly and sequence annotation

Genomic DNA libraries were prepared and sequenced at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (WTSI) in Hinxton, UK, using the Illumina Hiseq 2000 platform (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). This generated paired-end sequence reads of 100 bp. The sequence reads were trimmed and checked for quality using an average base pair quality score of at least 20 per read. We used Velvet v1.2.09,20 a de novo sequence assembly method that uses the De Bruijn graph approach to generate contiguous sequences (contigs) by selecting the optimal k-mers using VelvetOptimiser.21 Assembled contigs with <300 bp were excluded from the dataset and the remaining contigs were scaffolded using SSPACE Basic v2.0.22 The gaps between contigs were filled by GapFiller v1.10.23 Sequence assemblies were annotated using the Prokka v1.11 bacterial annotation pipeline.24 Sequence reads were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA). Isolate accession numbers, sequencing and assembly statistics are included in Table S1 (available as Supplementary data at JAC Online).

Phylogeny reconstruction and inference of population structure

The Roary pan-genome pipeline25 was used to construct the core genome of the 94 E. coli strains using the annotated genome assemblies. Genes were classified as ‘core’ if they were identified in at least 99% of the isolates. All genes present in <99% of the isolates were classified as ‘accessory’. We aligned each core gene and concatenated all the alignments to generate a single core-gene multiple sequence alignment, which was used to construct a maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree using RAxML v.7.8.6.26 RAxML was run under the General Time Reversible (GTR) substitution model with a Gamma rate of correction heterogeneity. The reliability of the inferred branches and branch partitions in the phylogenetic tree were assessed using 100 bootstrap replicates.

To determine the underlying genomic population structure of the study isolates, we mapped the sequence reads for all 94 isolates onto the E. coli strain K12 sub-strain MG1655 reference whole-genome sequence (accession number U00096) using Burrows Wheeler Aligner (BWA).27 Realignment of the insertion and deletion (indel) sites in the generated binary alignment map (BAM) files for the isolates was performed using GATK v3.3.0.28 The consensus pseudo-sequences were generated from each BAM file and aligned with other sequences to generate whole-genome alignment of the study isolates. We adjusted for recombination and used Gubbins29 to remove recombination sites from the whole-genome alignment and then generated an alignment of polymorphic (variable) sites only using SNP-Sites.30 An ML phylogenetic tree was then reconstructed using this SNP alignment, again using RAxML with the same parameters used to construct the core-gene alignment tree. Topologies of the core-gene alignment tree and mapping (to reference) alignment SNP tree were compared by a tanglegram drawn with a dendroscope.31 This SNP alignment was also used to cluster the isolates into unique subpopulations or sequence clusters (SCs) using the hierBAPS module in the Bayesian analysis of population structure (BAPS) v6.0 software.32

In silico molecular typing of study isolates

We did in silico MLST33 and PCR to determine the STs and phylogroups of study isolates. MLST was performed using seven housekeeping genes, namely adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA and recA (http://mlst.warwick.ac.uk/mlst/dbs/Ecoli). For phylogroup typing, a two-stage in silico quadruplex PCR was performed as described previously by Clermont et al.34 In brief, the first stage of the PCR used four primers: arpA, chuA, yjaA and TspE.C2. If a given isolate’s phylogroup could not be resolved from the first stage, a second stage was performed that included two more primer sequences, trpAgpC and arpAgpC.

Determination of antimicrobial resistance and plasmid typing

Acquired AMR genes were searched for by BLAST,35 using a database of acquired AMR genes curated at WTSI based on the ResFinder database.36 Presence of a gene in an isolate was confirmed if its assembled genome sequence had at least 95% nucleotide identity match with a gene in the database and a coverage of at least 90% of the length of the database match. We analysed translated nucleotide sequence alignments of the gyrA, gyrB, parC and parE genes to identify specific amino acid mutations that were associated with fluoroquinolone resistance. In silico plasmid typing was done by searching for plasmid replicons against the PlasmidFinder database.37

Statistical analyses

Proportions were compared using Fisher’s exact test or the χ2 test where appropriate and means of pairwise SNP differences for identified clades were compared using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). We used the power-law regression equation to model the expansion of the pan-genome in relation to number of isolates. All statistical analyses were done using R v3.3.1 (R Core Team, www.r-project.org).

Results

Pan-genome of Malawian E. coli isolates

Ninety-four E. coli strains were sequenced and included for comparative genomic analysis. Automated annotation predicted an average of 4845 genes per isolate, which resulted in an overall pan-genome consisting of 22 934 genes. Genes were considered to be the same if they were identical in at least 95% of the nucleotide positions. The core gene set comprised 2210 genes, which is equivalent to 9.6% of the pan-genome size and 45.6% of the average whole genome size, while the accessory gene set consisted of 20 724 genes, i.e. 90.4% of the pan-genome size. The cumulative number of genes in the pan-genome, the number of core genes per subset of isolates, the number of isolate-specific (unique) genes per subset of isolates and the number of newly identified genes when more genomes were added to the collection were identified (Figure S1). The pan-genome analysis has shown that the E. coli population in Blantyre, Malawi, has an open pan-genome (Figure S2), consistent with previous studies.38,39 This implies that the pan-genome will continue to expand with the inclusion of more genome sequences. The majority of the newly discovered genes with an increasing number of isolates were unique (Figure S1) and approximately one-third of the total accessory genes consisted of strain-specific genes.

Sequence types and phylogroups

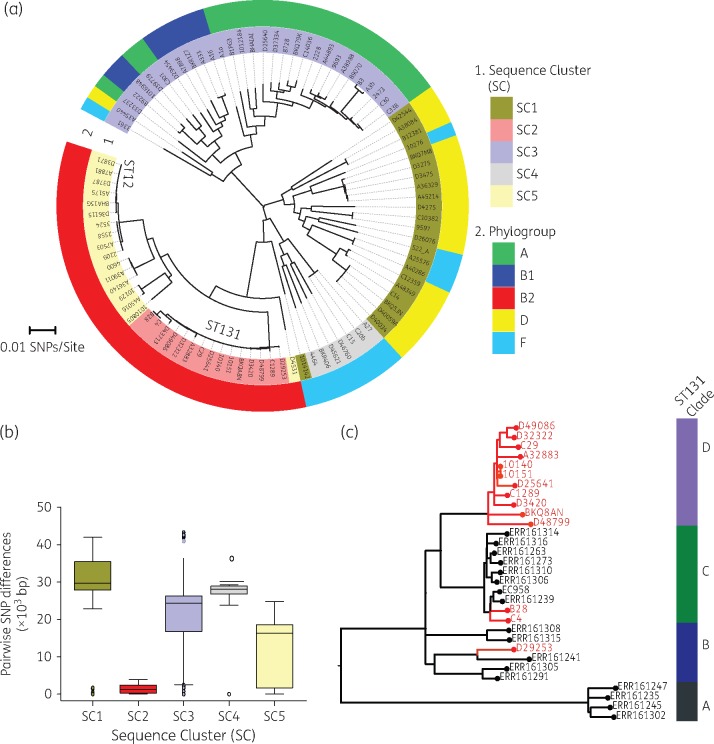

The degree of sequence diversity in the study isolates was further analysed using MLST and phylogrouping. Our results from MLST showed that the E. coli isolates belonged to 45 different STs. Seven of the isolates could not be uniquely typed by MLST. ST131 was the most common ST, identified in 14.9% (14/94) of the isolates, and was followed by ST12, which was present in 9.6% (9/94) of the isolates. Other common STs included ST69 (5.0%), ST10 (5.0%) and ST391 (4.0%). Overall, a total of five phylogroups, namely A, B1, B2, D and F, were identified in the study isolates. Phylogroup B2, which was predominantly composed of ST131 and ST12 isolates, was the largest phylogroup in this collection (Figure 1a), containing 34.0% (32/94) of the isolates. Phylogroup A was the second largest phylogroup with 23.4% (22/94) isolates.

Figure 1.

Genomic population structure and relatedness of E. coli isolates collected from Blantyre, Malawi. (a) Circular ML core-genome phylogenetic tree of Malawian E. coli isolates rooted at mid-point of the longest branch separating the two most divergent isolates. The inner ring designates identified SCs by hierBAPS and the outer ring designates phylogroups identified by in silico PCR. (b) Distribution of pairwise SNP differences in each of the five clades to demonstrate the variations in sequence diversity in each clade. (c) An ML phylogenetic tree, constructed from recombination-free SNP alignment of Malawian ST131 isolates (red branches) in the context of previously published global ST131 isolates (black branches). This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the printed version of JAC.

Population structure of Malawian E. coli isolates

A population structure analysis using the hierBAPS sequence-clustering approach clustered the 94 E. coli isolates into five clades or SCs designated SC1–SC5. The inferred SCs correlated with the E. coli phylogroups described in the previous section (Figure 1a). The SCs showed significant differences in nucleotide sequence diversity (P < 0.001) as demonstrated by the distribution of pairwise SNP differences in each cluster (Figure 1b). The phylogeny reconstructed from the core genome was compared with that reconstructed from whole-genome sequence data adjusted for recombination, and this revealed a similar topology (Figure S3). The phylogenetic clades inferred from the core-genome ML phylogenetic tree were also consistent with the hierBAPS clusters. SC2 and SC5 showed the lowest within-cluster sequence diversity, characterized by short phylogenetic branches and lower average pairwise SNP differences of 1419 and 12 300 core-genome SNPs, respectively. In comparison, SC1, SC3 and SC4 demonstrated higher average pairwise SNP differences of 29 010, 22 230 and 23 950 core-genome SNPs, respectively (Figure 1b). The highly divergent clusters, namely SC1, SC3 and SC4, comprised diverse sets of STs, i.e. 9 STs in SC1, 23 STs in SC3 and 6 STs in SC4; the less diverse SCs, namely SC2 and SC5, on the other hand, were principally associated with ST131 and ST12. Except for SC5, which comprised blood culture isolates only (Figure 2), there was generally no clustering of isolates specific to either source of isolation or patients’ age group.

Figure 2.

Distribution of AMR phenotype profiles, acquired AMR genes and plasmid incompatibility groups across the phylogeny of Malawian E. coli isolates. On the left is the ML core-genome phylogeny of the E. coli isolates from Malawi. The first two columns at the termini of the phylogeny represent the clinical source of isolation and STs for each isolate, respectively. Immediately following the two columns are six columns that represent the AMR phenotype profile. The next two panels following the AMR phenotype profiles are columns that represent presence and absence of AMR genes and plasmid replicons. This figure appears in colour in the online version of JAC and in black and white in the printed version of JAC.

To understand the Malawian ST131 isolates in the context of other global isolates, we mapped the 14 Malawian ST131 genomes and selected 17 previously published ST131 genomes (from all three identified ST131 clades)40 to the ST131 EC958 reference genome and generated an ML phylogeny from recombination-free SNP alignment. Two CTX-M-15 isolates from Malawi (B28 and C4) clustered with isolates from the CTX-M-15-associated sub-clade C, whereas one CTX-M-15 isolate (BKQ8AN) clustered with the rest of the other Malawian non-CTX-M-15 isolates into a sub-clade that we have designated D, which was distinct from the previously known sub-clades A, B and C (Figure 1c).

Genetic determinants of antimicrobial resistance in E. coli

Our analysis identified a total of 25 unique AMR genes known to encode proteins conferring resistance to a range of different classes of antimicrobial compounds, including aminoglycosides, β-lactams, chloramphenicol, sulphonamides, trimethoprim, tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones (Table 1). AMR genes, especially those present in at least four isolates, were distributed across the E. coli phylogeny independent of phylogenetic clustering of the host isolates (Figure 2). Similar to phylogenetic clustering, there were no specific AMR genotypes associated with isolates from a particular source or patient age group.

Table 1.

Distribution of AMR genes among Malawian E. coli isolates

| Gene | Known AMR phenotype | Isolates, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| sul2 | sulphonamides | 88 (93.6) |

| strA | aminoglycosides | 87 (92.6) |

| strB | aminoglycosides | 87 (92.6) |

| dfrA | trimethoprim | 86 (91.5) |

| blaTEM-1 | β-lactams | 74 (78.7) |

| catA | chloramphenicol | 61 (64.9) |

| sul1 | sulphonamides | 51 (54.3) |

| tetB | tetracycline | 51 (54.3) |

| aac3-IIa | aminoglycosides | 37 (39.4) |

| tetA | tetracycline | 38 (40.4) |

| mphA | macrolides | 35 (37.2) |

| blaCTX-M-15 | ESBL | 20 (21.3) |

| blaOXA-1 | β-lactams | 20 (21.3) |

| aac(6ʹ)-Ib-cr | aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolone | 18 (19.1) |

| aph3 | aminoglycosides | 15 (16.0) |

| qnrB1 | fluoroquinolones | 4 (4.3) |

| floR | chloramphenicol | 3 (3.2) |

| blaSCO-1 | β-lactams | 2 (2.1) |

| aadA2 | aminoglycosides | 2 (2.1) |

| blaSHV-12 | ESBL | 2 (2.1) |

| catB | chloramphenicol | 2 (2.1) |

| cmlA1 | chloramphenicol | 1 (1.1) |

| blaOXA-10 | ESBL | 1 (1.1) |

| blaSHV-1 | β-lactam | 1 (1.1) |

| qepA | quinolones | 1 (1.1) |

β-Lactam and ESBL resistance

We identified seven genes associated with β-lactam resistance, including three ESBL genes (Table 1). Narrow-spectrum β-lactamases included blaTEM-1 (74/94 isolates), blaOXA-1 (20/94 isolates), blaSCO-1 (2/94 isolates) and blaSHV-1 (1/94 isolates). Twenty-one out of 94 (22.3%) isolates carried at least one ESBL gene, of which blaCTX-M-15 was the most common (Table 1), being present in 20/21 (95.2%) of the isolates carrying an ESBL gene. The blaCTX-M-15 gene was significantly associated with resistance to cephalosporins (P < 0.001), with 19/20 isolates carrying the bla-CTX-M-15 gene being resistant to ceftriaxone by disc testing. The ceftriaxone resistance phenotype was not known for the remaining isolate with the blaCTX-M15 gene. Other ESBLs detected included blaSHV-12 (one isolate) and blaOXA-10 (one isolate), and both isolates had expressed phenotypic resistance to ceftriaxone. Similar to all common AMR genes identified in this collection, the blaCTX-M-15 gene was present in isolates independent of phylogenetic clustering. The distribution of isolates carrying blaCTX-M-15 showed that the gene was present in isolates from five identified phylogroups and 11 STs, most commonly ST391 (4/4 isolates), ST648 (3/3 isolates) and ST131 [3/14 (21.4%) isolates] (Table 2). The blaCTX-M-15 genes were found to be located in both the chromosome (5/20 isolates) and plasmid DNA (15/20 isolates), but their location was always downstream and adjacent to the ISEcp1 element.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Malawian CTX-M-15-associated E. coli isolates

| Isolate ID | Year of isolation | Source | ST | Phylogroup | Genome locus | Plasmid replicon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D42544 | 2007 | blood | 1084 | D | plasmid | FIB, FII, HI2 |

| BKQA8N | 2013 | blood | 131 | B2 | chromosome | FIB, FII, HI2, P, Q1 |

| C4 | — | CSF | 131 | B2 | chromosome | Col, FIA, FIB, Q1 |

| B28 | 2009 | RS | 131 | B2 | chromosome | Col, FIA, FII, X4, Y |

| C30 | 2009 | RS | 167 | A | plasmid | FIA, FIB, FII, I2, Y |

| C33b | — | CSF | 167 | A | plasmid | FIA, FIB, FII, I2, P, Y |

| 1012184 | 2011 | blood | 361 | A | plasmid | FIB, FII |

| D40034 | 2006 | blood | 391 | D | plasmid | FIB, FIA, X1 |

| BKQ5JN | 2013 | blood | 391 | D | plasmid | FIB, FIA, X1, X4 |

| D40059A | 2006 | blood | 391 | D | plasmid | FIA, FIB, X1 |

| C14 | — | CSF | 391 | D | plasmid | A/C, FIA, FIB, FII, Q1 |

| A1a | 2009 | RS | 399 | A | plasmid | HI2, Y |

| A16 | 2009 | blood | 448 | B1 | plasmid | A/C, FIA, FIB, FII, Q1 |

| A3b | 2009 | RS | 617 | A | plasmid | FIA, FIB, FII |

| A27 | 2009 | RS | 648 | F | chromosome | FIA, FIB, FII |

| C15 | — | CSF | 648 | F | chromosome | FIA, FIB, FII |

| C20b | 2009 | RS | 648 | F | chromosome | Col, FIA, FIB, FII |

| 1016948 | 2011 | CSF | 977 | B1 | plasmid | Y |

| 1014142 | 2011 | blood | 1163 | F | plasmid | FIA, FIB, FII, Q1, Y |

RS, rectal swab.

Fluoroquinolone resistance

We translated the aligned nucleotide sequences of each gene into protein sequences. The amino acid products of the gyrA gene alignment were highly conserved. However, we identified amino acid substitutions at codon position 83 from serine (S) to leucine (L), (S83L), in 17.0% (16/94) and serine (S) to alanine (A), (S83A), in 2.1% (2/94) of the isolates, and also at codon position 87, which showed a change from aspartic acid (D) to asparagine (N), (D87N), in 14.9% (14/94) of the isolates. Fourteen isolates had mutations at both codon positions 83 and 87 and all of them showed in vitro resistance to ciprofloxacin, whereas two isolates had only one codon mutation at position 83 and they were fluoroquinolone susceptible. In addition to the identified fluoroquinolone mutations, we also identified four isolates carrying the horizontally acquired plasmid-mediated fluoroquinolone resistance gene qnrB. None of the four isolates carrying the qnrB gene had the gyrA fluoroquinolone resistance mutations, but three isolates showed reduced susceptibility to fluoroquinolones.

Aminoglycoside resistance

Six genes known to confer resistance to aminoglycosides were identified in this dataset. These include strA and strB in 87/94 (92.6%) isolates, aac3-IIa in 37/94 (39.4%) isolates, aac(6′)-Ib-cr in 18/94 (19.1%) isolates, aph3 in 15/94 (16.0%) isolates and aadA in 2/94 (2.1%) isolates (Table 1). Both aac3-IIa and aac(6′)-Ib-cr were associated with gentamicin as well as fluoroquinolone resistance phenotypes (P < 0.001). Together, strA and strB are known to confer resistance to streptomycin, which is only used in Malawi for re-treatment of TB, and there was no significant association between these genes and gentamicin resistance phenotype (P = 0.318).

Chloramphenicol resistance

Four genes known to encode chloramphenicol resistance were identified: catA in 61/94 (64.9%) isolates; floR in 3/94 (3.2%) isolates; catB in 2/94 (2.1%) isolates; and cmlA1 in 1/94 (1.1%) isolates (Table 1). The in silico predictions were confirmed by phenotypic resistance data, with chloramphenicol resistance being strongly associated with the presence of the catA gene (P < 0.001). All three isolates carrying the floR gene had a chloramphenicol resistance phenotype, whereas the isolate with the cmlA1 gene was susceptible to chloramphenicol. The isolate with the catB gene also had the catA gene and was chloramphenicol resistant.

Plasmid incompatibility groups

A search against the PlasmidFinder database identified a total of 15 different plasmid replicons (including FIA, FIB, FII, Col, A/C, HI1B, HI2, B/O/K/Z, I2, Q, P, p0111, R, X4 and Y) to be present in our collection of E. coli isolates (Figure 2). FIB, FIA and FII were the most common plasmid replicons across all the 94 isolates (Figure 2) but also amongst isolates that had the blaCTX-M-15 gene (Table 2). One IncFIB plasmid was similar to pNDM-Mar1 (GenBank accession number JN420336), a plasmid known to encode the carbapenem resistance gene blaNDM-1, although no carbapenem resistance gene was identified in this dataset.

Discussion

E. coli is well known to be a highly diverse species13 that is strongly associated with AMR. In this study, we whole-genome sequenced 94 E. coli isolates collected in Blantyre, Malawi, situated in a region from which such data are severely lacking. We reveal that E. coli in this setting has an expanding pan-genome, and high diversity in phylogenetic clustering, STs and phylogroups consistent with the known global diversity. Furthermore, we demonstrate that AMR, in particular ESBL resistance, in Malawi has emerged across a diverse range of E. coli lineages containing a number of similar resistance genes.

The most commonly identified ESBL gene was blaCTX-M-15, present in 11 STs and all five identified phylogroups, including all ST391 genomes, 3/14 ST131 genomes and a number of other clonally diverse STs (Table 2). Within SSA, a high diversity of CTX-M-15-associated STs has also been reported in Tanzania,11 whereas globally the blaCTX-M-15 gene has been more strongly associated with a sub-lineage of ST131, H30-Rx.41 The predominance of this ST131 sub-lineage as a CTX-M-15 clone has been reported in Asia, Europe, North Africa and South America.7,42–45 Further work is required in Malawi to accurately estimate the prevalence of blaCTX-M-15 across the different clades causing drug-resistant infection.

ST131 isolates in this study constitute the most clonal SC in the population structure of our collection, suggesting that they were the most recent lineage to emerge or arrive in this setting. A previous study of a global collection of ST131 isolates identified three sub-lineages of the ST131 isolates, which were designated A, B and C.40 When put in the context of these global ST131 isolates, the majority of the Malawian ST131 isolates form a sub-lineage distinct from these previously identified sub-lineages (Figure 1c). Furthermore, whilst two of the three CTX-M-15 isolates from Malawi cluster in the CTX-M-15-associated sub-lineage C, one clusters with the rest of the other Malawian isolates in sub-clade D. The CTX-M-15-associated ST131 clone is reported to have emerged in the early to mid 2000s7 and has since spread in a series of clonal expansions to become the most dominant E. coli clone, causing a spectrum of extra-intestinal infections, including urinary tract infections, bacteraemia, pneumonia, and intra-abdominal and wound infections.44 In our collection, the earliest CTX-M-15-associated ST131 isolate was isolated in 2009, and although the CTX-M-15 ST131 clone might have emerged earlier in this setting, a previous study of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in 2004–05 did not identify CTX-M-15-producing E. coli.46 It is therefore likely that CTX-M-15-associated ST131 emerged or arrived in this setting a few years after its emergence in Europe and North America.

In this study, we have further shown that the blaCTX-M-15 gene exists in genetically heterogeneous strains even within the ST131 lineage (Figure 1a and c). It is not only the case that blaCTX-M-15 was distributed across phylogenetically diverse isolates, but fluoroquinolone resistance genotypes and all other common AMR genes, including dfrA, sul1, sul2, strA, strB, blaTEM-1, catA and tetB, were also widely distributed. The set of common AMR genes, namely dfrA, sul1, sul2, strA, strB, blaTEM-1, catA and tetB, has previously been characterized in MDR Salmonella circulating in Blantyre but, unlike with E. coli, these were associated with epidemic clades.47,48

In conclusion, this study has revealed a high diversity of lineages of E. coli circulating in Malawi and associated with AMR, including ESBL and fluoroquinolone resistance. Further work is required to ascertain which clades are the predominant cause of drug-resistant infection in this setting. The data highlight the value of longitudinal bacteraemia surveillance coupled with detailed molecular epidemiology in all settings in describing the global epidemiology of ESBL resistance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the clinical and laboratory staff at the Malawi-Liverpool-Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Programme and the library preparation, sequencing and core informatics teams at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute.

Funding

This work was supported by Wellcome Trust grant number 098051 and Malawi National Commission of Science and Technology through the Health Research Capacity Strengthening Initiative (HRCSI). Malawi-Liverpool-Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Programme (MLW) is supported by the Wellcome Trust Major Overseas Programme Core Grant number 101113/Z/13/E. P. M. is supported by the Human Heredity and Health for Africa Bioinformatics Network (H3ABioNet) in form of a PhD studentship. A. E. M. is supported by a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) grant BB/M014088/1.

The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication. The corresponding author was responsible for the decision to submit the work for publication.

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Author contributions

P. M., N. A. F., R. S. H., D. B. E. and C. L. M. conceived and designed the study. D. B. E., N. A. F., N. R. T. and C. L. M. supervised the study. C. L. M., C. P., M. K., K. J. G. and S. T. prepared and provided clinical samples. P. M. carried out the bioinformatics and statistical analyses and prepared tables and figures. A. K. C., T. K., C. C. and A. E. M. assisted with planning the bioinformatics analyses. P. M., N. A. F., N. R. T. and C. L. M. interpreted the results and drafted the manuscript. P. M., N. A. F., A. K. C., T. K., C. C., R. S. H., A. E. M., D. B. E., N. R. T. and C. L. M. contributed to the discussions and reviewed the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary data

Figures S1–S3 and Table S1 are available as Supplementary data at JAC Online (http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/).

References

- 1. Reddy EA, Shaw AV, Crump JA.. Community-acquired bloodstream infections in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10: 417–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC. et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet 2013; 382: 209–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S. et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet 2012; 379: 2151–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peirano G, Bradford PA, Kazmierczak KM. et al. Global incidence of carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli ST131. Emerg Infect Dis 2014; 20: 1928–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Navon-Venezia S, Chmelnitsky I, Leavitt A. et al. Plasmid-mediated imipenem-hydrolyzing enzyme KPC-2 among multiple carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli clones in Israel. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006; 50: 3098–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nordmann P, Naas T, Poirel L.. Global spread of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 17: 1791–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Blanco J, Leflon-Guibout V. et al. Intercontinental emergence of Escherichia coli clone O25:H4-ST131 producing CTX-M-15. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008; 61: 273–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. D'Andrea MM, Arena F, Pallecchi L. et al. CTX-M-type β-lactamases: a successful story of antibiotic resistance. Int J Med Microbiol 2013; 303: 305–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Makoka MH, Miller WC, Hoffman IF. et al. Bacterial infections in Lilongwe, Malawi: aetiology and antibiotic resistance. BMC Infect Dis 2012; 12: 67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tansarli GS, Athanasiou S, Falagas ME.. Evaluation of antimicrobial susceptibility of Enterobacteriaceae causing urinary tract infections in Africa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57: 3628–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mshana SE, Falgenhauer L, Mirambo MM. et al. Predictors of blaCTX-M-15 in varieties of Escherichia coli genotypes from humans in community settings in Mwanza, Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis 2016; 16: 187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peirano G, van Greune CH, Pitout JD.. Characteristics of infections caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli from community hospitals in South Africa. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2011; 69: 449–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chaudhuri RR, Henderson IR.. The evolution of the Escherichia coli phylogeny. Infect Genet Evol 2012; 12: 214–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Matsumura Y, Johnson JR, Yamamoto M. et al. CTX-M-27- and CTX-M-14-producing, ciprofloxacin-resistant Escherichia coli of the H30 subclonal group within ST131 drive a Japanese regional ESBL epidemic. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015; 70: 1639–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Peirano G, Richardson D, Nigrin J. et al. High prevalence of ST131 isolates producing CTX-M-15 and CTX-M-14 among extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolates from Canada. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54: 1327–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hooper DC, Jacoby GA.. Mechanisms of drug resistance: quinolone resistance. Ann NY Acad Sci 2015; 1354: 12–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feasey NA, Masesa C, Jassi C. et al. Three epidemics of invasive multidrug-resistant Salmonella bloodstream infection in Blantyre, Malawi, 1998-2014. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61 Suppl 4: S363–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wall EC, Everett DB, Mukaka M. et al. Bacterial meningitis in Malawian adults, adolescents, and children during the era of antiretroviral scale-up and Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccination, 2000-2012. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58: e137–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Everett DB, Mukaka M, Denis B. et al. Ten years of surveillance for invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae during the era of antiretroviral scale-up and cotrimoxazole prophylaxis in Malawi. PloS One 2011; 6: e17765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zerbino DR, Birney E.. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res 2008; 18: 821–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zerbino DR, Using the Velvet de novo assembler for short-read sequencing technologies. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics 2010; Chapter 11: Unit 11.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boetzer M, Henkel CV, Jansen HJ. et al. Scaffolding pre-assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics 2011; 27: 578–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nadalin F, Vezzi F, Policriti A.. GapFiller: a de novo assembly approach to fill the gap within paired reads. BMC Bioinformatics 2012; 13 Suppl 14: S8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014; 30: 2068–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Page AJ, Cummins CA, Hunt M. et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics 2015; 31: 3691–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014; 30: 1312–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li H, Durbin R.. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009; 25: 1754–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E. et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 2010; 20: 1297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Croucher NJ, Page AJ, Connor TR. et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res 2015; 43: e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Page AJ, Taylor B, Delaney AJ. et al. SNP-sites: rapid efficient extraction of SNPs from multi-FASTA alignments. Microbial Genomics 2016; 2; doi: 10.1099/mgen.0.000056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huson DH, Scornavacca C.. Dendroscope 3: an interactive tool for rooted phylogenetic trees and networks. Syst Biol 2012; 61: 1061–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Corander J, Tang J.. Bayesian analysis of population structure based on linked molecular information. Math Biosci 2007; 205: 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maiden MC, Bygraves JA, Feil E. et al. Multilocus sequence typing: a portable approach to the identification of clones within populations of pathogenic microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998; 95: 3140–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Clermont O, Christenson JK, Denamur E. et al. The Clermont Escherichia coli phylo-typing method revisited: improvement of specificity and detection of new phylo-groups. Environ Microbiol Rep 2013; 5: 58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W. et al. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 1990; 215: 403–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S. et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother 2012; 67: 2640–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Carattoli A, Zankari E, Garcia-Fernandez A. et al. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 3895–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Touchon M, Hoede C, Tenaillon O. et al. Organised genome dynamics in the Escherichia coli species results in highly diverse adaptive paths. PLoS Genet 2009; 5: e1000344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Snipen L, Almoy T, Ussery DW.. Microbial comparative pan-genomics using binomial mixture models. BMC Genomics 2009; 10: 385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Petty NK, Ben Zakour NL, Stanton-Cook M. et al. Global dissemination of a multidrug resistant Escherichia coli clone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: 5694–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Price LB, Johnson JR, Aziz M. et al. The epidemic of extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli ST131 is driven by a single highly pathogenic subclone, H30-Rx. mBio 2013; 4: e00377-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Bertrand X, Madec JY.. Escherichia coli ST131, an intriguing clonal group. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014; 27: 543–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ferjani S, Saidani M, Ennigrou S. et al. Multidrug resistance and high virulence genotype in uropathogenic Escherichia coli due to diffusion of ST131 clonal group producing CTX-M-15: an emerging problem in a Tunisian hospital. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2014; 59: 257–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen LF, Freeman JT, Nicholson B. et al. Widespread dissemination of CTX-M-15 genotype extended-spectrum-β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae among patients presenting to community hospitals in the southeastern United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 1200–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hussain A, Ranjan A, Nandanwar N. et al. Genotypic and phenotypic profiles of Escherichia coli isolates belonging to clinical sequence type 131 (ST131), clinical non-ST131, and fecal non-ST131 lineages from India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 7240–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gray KJ, Wilson LK, Phiri A. et al. Identification and characterization of ceftriaxone resistance and extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Malawian bacteraemic Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006; 57: 661–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Okoro CK, Kingsley RA, Connor TR. et al. Intracontinental spread of human invasive Salmonella typhimurium pathovariants in sub-Saharan Africa. Nat Genet 2012; 44: 1215–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Feasey NA, Gaskell K, Wong V. et al. Rapid emergence of multidrug resistant, H58-lineage Salmonella Typhi in Blantyre, Malawi. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015; 9: e0003748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.