Abstract

AIM

To investigate the plasma amino acid response and tolerance to normal or high protein meals in patients with cirrhosis.

METHODS

The plasma amino acid response to a 20 g mixed protein meal was compared in 8 biopsy-proven compensated cirrhotic patients and 6 healthy subjects. In addition the response to a high protein meal (1 g/kg body weight) was studied in 6 decompensated biopsy-proven cirrhotics in order to evaluate their protein tolerance and the likelihood of developing hepatic encephalopathy (HE) following a porto-caval shunt procedure. To test for covert HE, the “number connection test” (NCT) was done on all patients, and an electroencephalogram was recorded in patients considered to be at Child-Pugh C stage.

RESULTS

The changes in plasma amino acids after a 20 g protein meal were similar in healthy subjects and in cirrhotics except for a significantly greater increase (P < 0.05) in isoleucine, leucine and tyrosine concentrations in the cirrhotics. The baseline branched chain amino acids/aromatic amino acids (BCAA/AAA) ratio was higher in the healthy persons and remained stable-but it decreased significantly after the meal in the cirrhotic group. After the high protein meal there was a marked increase in the levels of most amino acids, but only small changes occurred in the levels of taurine, citrulline, cysteine and histidine.The BCAA/AAA ratio was significantly higher 180 and 240 min after the meal. Slightly elevated basal plasma ammonia levels showed no particular pattern. Overt HE was not observed in any patients.

CONCLUSION

Patients with stable liver disease tolerate natural mixed meals with a standard protein content. The response to a high protein meal in decompensated cirrhotics suggests accumulation of some amino acids but it did not precipitate HE. These results support current nutritional guidelines that recommend a protein intake of 1.2-1.5 g/kg body weight/day for patients with cirrhosis.

Keywords: Branched chain amino acids, Fischer’s ratio, Liver, Protein, Cirrhosis, Tolerance, Nutrition, Amino acids, Diet

Core tip: In this study we investigated the plasma amino acid response to standard and high protein meals in patients with liver cirrhosis and looked for evidence of protein intolerance by testing for the presence of either covert or overt hepatic encephalopathy. We sought to improve on previous methodology by selecting a more homogeneous group of patients with biopsy proven cirrhosis, and by using natural mixed protein meals at two protein levels: A standard (20 g) meal and a high (1 g/kg per body weight) protein meal. We found small differences in the plasma amino acid changes after the standard protein meal but there were marked increments in most amino acids after the high protein meal. Noteworthy no patient showed overt clinical sings of encephalopathy and minor electroencephalo-graph changes were seen in only one patient after the high protein meal. These results present experimental evidence to support current nutritional guidelines for patients with cirrhosis.

INTRODUCTION

The liver plays a key role in the metabolism of amino acids and controls, to a great extent, their homeostasis in the plasma free amino acid pool; it removes them from the plasma, interconverts them and may incorporate them into new protein molecules. Consequently, patients with liver disease show abnormalities in their plasma amino-acid profile[1-4] and the fact that some patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis develop protein intolerance[5] has been a matter of major clinical concern over the years[6]. The plasma amino acid increase after ingestion of amino acids or protein tends to be associated with an increase in plasma ammonia, which in turn has been implicated in the development of hepatic encephalopathy (HE)[7-9]. Under normal circumstances ammonia is detoxified in the liver.

Several studies have investigated the effect of protein ingestion on circulating amino acid levels in patients with liver cirrhosis. The findings have been used to plan therapeutic interventions involving the use of different mixtures of amino acids either to improve nutritional status or as an adjunct in the treatment of HE[10-13].

However, both the type and dosage of protein feed or formula and/or the routes of administration have been varied[3,14-17]. Nevertheless, even though most nutritional guidelines recommend high protein diets for liver cirrhosis protein restriction is still considered appropriate in some clinics[18,19]. The aim of this study was therefore to investigate the plasma amino acid response to a natural meal with normal protein content in compensated cirrhotic patients compared to a group of healthy subjects in accordance with current guidelines[18,20-22]. Furthermore, a group of patients with decompensated cirrhosis were studied in a protocol where they received a meal with high protein content. All the patients were tested for both covert and overt HE to examine the concept of “protein tolerance”.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects

We administered a 20 g mixed protein meal to 8 male patients with biopsy-proven compensated cirrhosis who were Child-Pugh class A (i.e., without complications of cirrhosis)[19]. Patients were recruited from the liver clinic at the Royal Free Hospital. A control group comprising 6 healthy age matched volunteers also received the 20 g protein meal. A group of 6 patients (5 male and 1 female) with biopsy-proven decompensated cirrhosis Child-Pugh class C (i.e., with ascites and esophageal varices but not HE) were also studied. They were being assessed for a porto-caval shunt procedure for the treatment of portal hypertension and so were studied before and after ingestion of a high protein meal (1 g protein/kg body weight). Exclusion criteria in this group were present or former HE and variceal bleeding within one week before the study. The high protein meal was used to predict the likelihood of HE developing following a shunt procedure[23]. To test for covert HE, the “number connection test” (NCT)[24] was performed in all patients and an electroencephalogram[25] was recorded in Child-Pugh stage C patients. This protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Royal Free Hospital and all patients agreed to participate in the study.

Test meals

Twenty grams protein meal: We recorded the self-selected meals of 10 in-patients with compensated cirrhosis (5 males and 5 females) in order to design a test meal. The lunch of the 10 patients contained on average 16.2 ± 1.6 g of protein, 44.6 ± 6.4 g of carbohydrates and 18.2 ± 3.2 g of fat. Afterwards we created a test meal consisting of beef, green beans, peach slices, ice cream and butter providing 546 kcal (2312.34 kJ), 19.4 g protein, 20.5 g fat and 76.5 g carbohydrate. The amino acid composition of the meal is presented in Table 1. To test for covert HE NCT were performed before and during the study at the same time as blood sampling and patients were checked for clinical signs of overt HE.

Table 1.

Amino acid content of the 20 g protein meal

| Amino acid | Content (mg) |

| Isoleucine | 934 |

| Leucine | 1500 |

| Lysine | 1588 |

| Methionine | 563 |

| Cysteine | 240 |

| Phenylalanine | 867 |

| Tyrosine | 723 |

| Threonine | 872 |

| Tryptophan | 255 |

| Arginine | 1161 |

| Histidine | 637 |

| Alanine | 1104 |

| Asparagine | 2109 |

| Glutamic acid | 3229 |

| Glycine | 935 |

| Proline | 999 |

| Serine | 901 |

One gram per kilogram of body weight protein meal: The Child-Pugh class C cirrhotics were allowed to select the source of protein from a variety of foods. Meat and chicken were the main sources of animal protein in the 1 g/kg of body weight protein dose. The proportions of fat and carbohydrate varied widely. The composition of the individual meals is shown in Table 2. Patients were also checked for clinical signs of overt HE, NCT were performed as mentioned previously, and an EEG was recorded before and 3 h after the meal.

Table 2.

Protein content of the 1 g/kg protein meals

| Patient | Energy (kcal) | Protein (g) | %kcal |

| 1 | 914 | 94 | 40 |

| 2 | 973 | 78 | 32 |

| 3 | 590 | 56 | 36 |

| 4 | 653 | 38 | 23 |

| 5 | 1545 | 78 | 20 |

| 6 | 1507 | 65 | 17 |

Blood samples

Samples were taken before the meal and at 30, 60, 120, 180 and 240 min and were processed as described previously[26]. In the healthy persons the 240 min sample was not taken.

Laboratory analysis

Plasma ammonia was measured by an enzymatic method (No. 170-UV Sigma Diagnostics, St Louis, MO, United States)[27] and amino acid levels on an LKB 4151 Alpha plus amino acid analyzer with a 200 mm × 4.6 mm high performance analytical column filled with Ultropac 8 cation-exchange resin[26]. Values for glutamine and glutamic acid were inaccurate as their apparent concentration depends on the time period between sampling and analysis. Tryptophan was not measured. Because of technical problems citrulline was not reported in the healthy control group. Total alpha-amino nitrogen was determined by the fluorodinitrobenzene (DNFB) method[28].

Statistical analysis

Differences in amino acid concentration between groups were compared using the Student’s “t” test and differences within a group by the paired “t” test.

RESULTS

Response to a 20 g protein meal

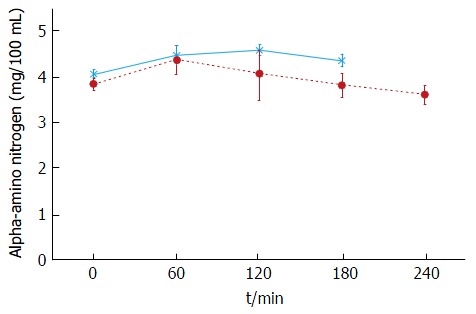

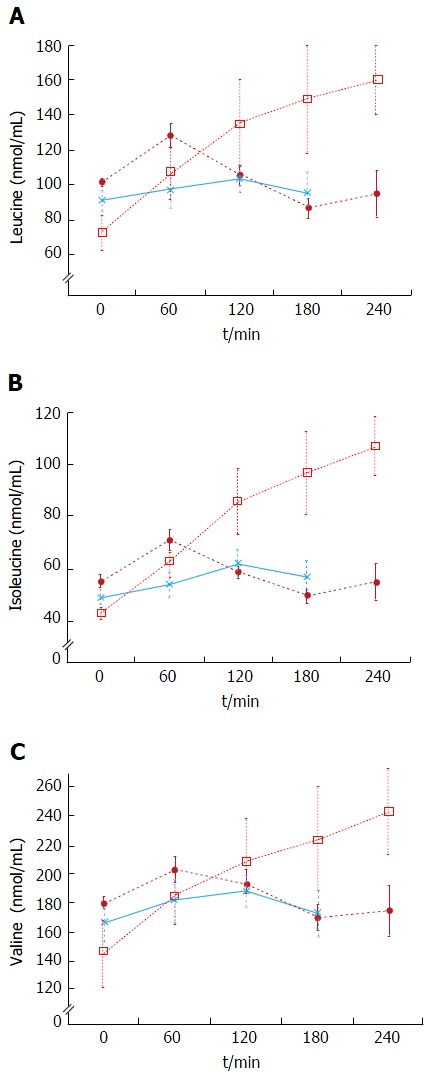

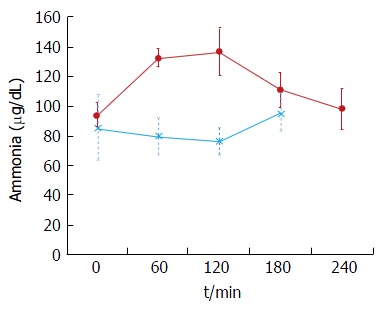

The plasma baseline levels of asparagine, cysteine, tyrosine and ornithine were significantly higher in the patients with stable cirrhosis compared to the healthy subjects (P < 0.05). The total alpha-amino-N response to the meal in the cirrhotic subjects did not differ from that of healthy subjects (Figure 1 and Table 3). However, as to individual amino acids, isoleucine, tyrosine and leucine increased significantly more in the cirrhotic patients (Figure 2). The baseline branched chain amino acids/aromatic amino acids (BCAA/AAA) ratio was higher in the healthy persons and remained stable after the meal while there was a further significant decrease after two hours in the cirrhotic group (Table 3). At 60 and 120 min cirrhotic patients showed a significant increase in plasma ammonia concentration after the meal than normal subjects (P < 0.01, Figure 3). The NCT remained normal and there were no clinical signs of HE.

Figure 1.

Plasma alpha-amino nitrogen concentration in response to a 20 g protein meal. Cirrhotic patients (n = 6), (closed circles); healthy subjects (n = 6), (asterix) (mean ± SEM).

Table 3.

Plasma amino acid response to a 20-g protein mixed meal in cirrhotic patients and controls

| Amino acid | Group | Basal (± SE) | 30 min (± SE) | 60 min (± SE) | 120 min (± SE) | 180 min (± SE) | 240 min (± SE) |

| Tau | Control | 69 ± 17 | 65 ± 10 | 74 ± 10 | 74 ± 11 | 69 ± 8 | |

| Cirrhotic | 48 ± 5 | 46 ± 7 | 42 ± 5a | 47 ± 6 | 44 ± 4 | 42 ± 7 | |

| Thr | Control | 101 ± 5 | 117 ± 10c | 110 ± 3 | 115 ± 8 | 114 ± 12 | |

| Cirrhotic | 113 ± 10 | 124 ± 8 | 125 ± 11 | 118 ± 8 | 101 ± 8 | 111 ± 15 | |

| Ser | Control | 94 ± 8 | 105 ± 8f | 104 ± 9d | 99 ± 11 | 92 ± 13 | |

| Cirrhotic | 105 ± 7 | 117 ± 8c | 114 ± 10 | 108 ± 9 | 96 ± 7 | 103 ± 12 | |

| Asn | Control | 23 ± 2 | 40 ± 2d | 41 ± 4d | 40 ± 4d | 35 ± 5c | |

| Cirrhotic | 35 ± 3a | 43 ± 3f | 44 ± 5d | 44 ± 4d | 37 ± 4 | 38 ± 5 | |

| Glu | Control | 246 ± 33 | 299 ± 35 | 263 ± 17 | 276 ± 24 | 237 ± 26 | |

| Cirrhotic | 375 ± 30 | 388 ± 20 | 380 ± 34 | 375 ± 23 | 354 ± 22 | 378 ± 45 | |

| Gln | Control | 163 ± 11 | 163 ± 14 | 154 ± 13 | 142 ± 11 | 144 ± 26 | |

| Cirrhotic | 226 ± 21ª | 217 ± 18 | 213 ± 14ª | 213 ± 20 | 190 ± 12 | 180 ± 29 | |

| Pro | Control | 145 ± 11 | 152 ± 13 | 151 ± 5 | 155 ± 12 | 135 ± 7 | |

| Cirrhotic | 152 ± 15 | 147 ± 17 | 173 ± 19 | 185 ± 17c | 155 ± 16 | 150 ± 15 | |

| Gly | Control | 178 ± 8 | 187 ± 11 | 190 ± 14 | 193 ± 16 | 176 ± 21 | |

| Cirrhotic | 174 ± 14 | 177 ± 14 | 166 ± 13 | 176 ± 11 | 170 ± 12 | 165 ± 16 | |

| Ala | Control | 271 ± 18 | 323 ± 21d | 339 ± 29d | 354 ± 31d | 309 ± 34 | |

| Cirrhotic | 262 ± 17 | 310 ± 24c | 334 ± 34 | 345 ± 25d | 307 ± 26 | 284 ± 38 | |

| Cit | |||||||

| Cirrhotic | 27 ± 3 | 23 ± 2 | 20 ± 2 | 27 ± 2 | 28 ± 2 | 33 ± 4 | |

| Val | Control | 167 ± 13 | 186 ± 14d | 182 ± 16c | 188 ± 11d | 173 ± 16 | |

| Cirrhotic | 180 ± 4 | 198 ± 10c | 203 ± 9c | 193 ± 10 | 170 ± 8 | 175 ± 18 | |

| Cys | Control | 42 ± 1 | 41 ± 2 | 40 ± 2 | 42 ± 3 | 39 ± 4 | |

| Cirrhotic | 58 ± 3b | 59 ± 2e | 60 ± 3e | 62 ± 2 | 58 ± 4b | 56 ± 5 | |

| Met | Control | 25 ± 2 | 24 ± 1 | 25 ± 1 | 29 ± 4 | 27 ± 4 | |

| Cirrhotic | 32 ± 3 | 30 ± 2a | 33 ± 3 | 31 ± 2 | 25 ± 3 | 25 ± 3 | |

| Iso | Control | 49 ± 3 | 55 ± 4 | 54 ± 5 | 62 ± 5 | 57 ± 7 | |

| Cirrhotic | 55 ± 2 | 68 ± 3a,d | 71 ± 4a,d | 59 ± 2 | 50 ± 3 | 55 ± 7 | |

| Leu | Control | 91 ± 6 | 101 ± 8c | 97 ± 10 | 103 ± 8 | 95 ± 11 | |

| Cirrhotic | 101 ± 2 | 126 ± 7a,d | 128 ± 7a,d | 106 ± 5 | 87 ± 5 | 95 ± 12 | |

| Tyr | Control | 53 ± 3 | 56 ± 2c | 55 ± 3 | 56 ± 4 | 54 ± 6 | |

| Cirrhotic | 73 ± 7a | 80 ± 7 | 83 ± 8b | 82 ± 8a | 73 ± 6 | 76 ± 10 | |

| Phe | Control | 37 ± 0.8 | 39 ± 1 | 40 ± 2 | 42 ± 4 | 40 ± 5 | |

| Cirrhotic | 48 ± 5 | 58 ± 7 | 61 ± 9 | 62 ± 9 | 57 ± 7 | 56 ± 7 | |

| Orn | Control | 41 ± 2 | 44 ± 2 | 44 ± 3 | 47 ± 3 | 45 ± 5 | |

| Cirrhotic | 61 ± 5b | 67 ± 4 | 69 ± 6 | 71 ± 7d | 68 ± 6 | 71 ± 11 | |

| Lys | Control | 145 ± 10 | 169 ± 13d | 175 ± 13d | 194 ± 13f | 169 ± 17c | |

| Cirrhotic | 144 ± 6 | 167 ± 9c | 171 ± 11c | 164 ± 11 | 153 ± 9 | 150 ± 15 | |

| His | Control | 64 ± 3 | 73 ± 3d | 72 ± 4c | 72 ± 4c | 67 ± 8 | |

| Cirrhotic | 63 ± 4 | 70 ± 3 | 73 ± 4 | 72 ± 4 | 69 ± 4 | 65 ± 5 | |

| Arg | Control | 70 ± 4 | 83 ± 5d | 85 ± 6c | 88 ± 6d | 77 ± 8 | |

| Cirrhotic | 73 ± 5 | 81 ± 6 | 85 ± 7 | 86 ± 6 | 80 ± 7 | 71 ± 8 | |

| BCAA/AAA | Control | 3.44 ± 0.2 | 3.62 ± 0.2 | 3.49 ± 0.2 | 3.65 ± 0.2 | 3.54 ± 0.2 | |

| Cirrhotic | 2.89 ± 0.2 | 2.97 ± 0.2 | 2.92 ± 0.2 | 2.62 ± 0.2c | 2.45 ± 0.2d | 2.53 ± 0.2f |

Plasma amino acid response to a 20 g protein mixed meal in cirrhotic patients and controls. The results are expressed as means ± SEM. Healthy subjects n = 6, cirrhotics n = 8. Plasma amino acids are given in nmol/mL; significantly different from the corresponding value of control subject:

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001; Significantly different from basal value within the same group

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Plasma leucine (A), isoleucine (B) and valine (C) concentrations in response to protein meals. Twenty grams protein meal, cirrhotics (n = 8), (closed circles); 20 g protein meal, healthy subjects (n = 6), (asterix) (mean ± SEM); 1 g/kg body weight protein meal, cirrhotics (n = 6), (open squares).

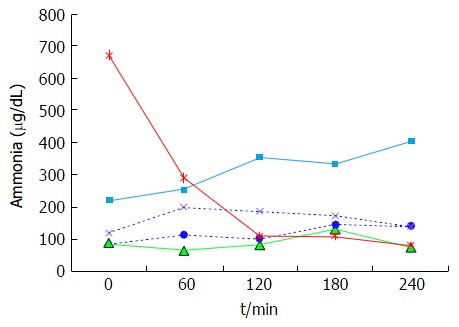

Figure 3.

Plasma ammonia concentrations in cirrhotic patients. Blood ammonia after a 20-g protein meal. Cirrhotic patients (n = 6), (closed circles); healthy subjects (n = 6), (asterix) (mean ± SEM).

Response to a 1 g/kg body weight protein meal

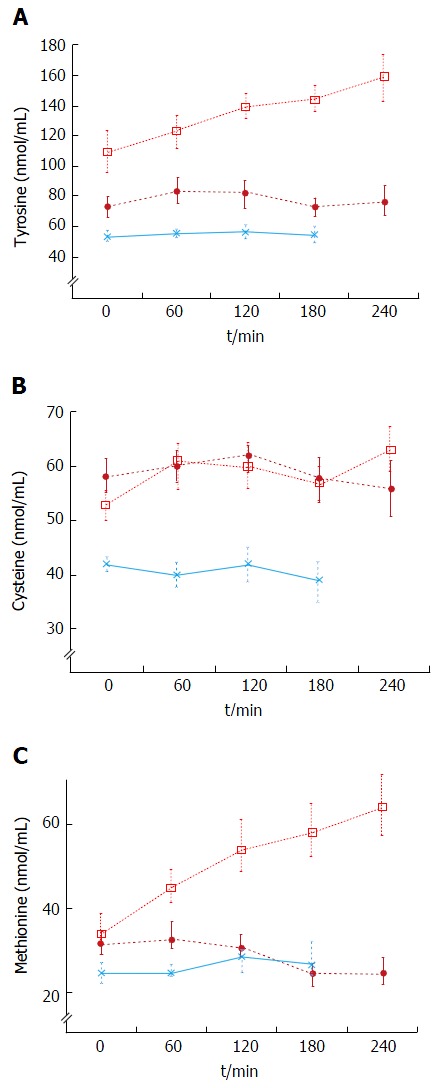

Decompensated cirrhotics had different basal concentration of some amino acids compared to those with stable cirrhosis (elevated: Alanine, tyrosine, decreased: isoleucine, leucine) (Figure 4 and Table 4). Hence, the BCAA/AAA ratio was significantly lower in the patients with unstable cirrhosis. After the meal, the concentration of most plasma amino acids (except for taurine, proline, citrulline, cysteine and histidine) had increased significantly at 120 min (Figure 4 and Table 4). Those increments were significantly larger than those observed in the 20 g protein group (Figure 1). The largest increases were observed in the cases of isoleucine (148%), leucine (119%) and methionine (88%) (Figures 1 and 3). The BCAA/AAA ratio was significantly higher 180 and 240 min after the meal (Table 4). Slightly elevated basal plasma ammonia levels increased in two patients, decreased in one and showed no change in two (Figure 3). After the protein meal only one patient presented mild electroencephalographic features of covert encephalopathy but there were no clinical manifestations.

Figure 4.

Plasma tyrosine (A), cysteine (B) and methionine (C) concentrations in response to protein meals. Twenty grams protein meal, cirrhotics (n = 8), (closed circles); 20 g protein meal, healthy subjects (n = 6), (asterix) (mean ± SEM); 1 g/kg body weight protein meal, cirrhotics (n = 6), (open squares).

Table 4.

Plasma amino acid response to a high (1 g protein/kg body weight) meal in cirrhotic patients

| Amino acid | Group | Basal (± SE) | 30 min (± SE) | 60 min (± SE) | 120 min (± SE) | 180 min (± SE) | 240 min (± SE) |

| Taurine | Cirrhotic | 58 ± 1 | 54 ± 4 | 59 ± 5 | 58 ± 3 | 57 ± 4 | 54 ± 3 |

| Threonine | Cirrhotic | 150 ± 25 | 152 ± 22 | 169 ± 23 | 195 ± 29c | 216 ± 43 | 216 ± 31 |

| Serine | Cirrhotic | 114 ± 11 | 131 ± 17 | 151 ± 20 | 153 ± 16f | 156 ± 21 | 158 ± 15 |

| Asparagine | Cirrhotic | 46 ± 3 | 60 ± 5 | 67 ± 6f | 76 ± 3 | 76 ± 7 | 73 ± 8 |

| Glutamic ac. | Cirrhotic | 110 ± 30 | 94 ± 25 | 88 ± 36 | 109 ± 29 | 130 ± 26 | 153 ± 79 |

| Glutamine | Cirrhotic | 449 ± 29 | 462 ± 64 | 514 ± 56 | 560 ± 43 | 578 ± 39 | 520 ± 82 |

| Proline | Cirrhotic | 182 ± 35 | 212 ± 30 | 220 ± 26 | 278 ± 30 | 266 ± 32 | 245 ± 34 |

| Glycine | Cirrhotic | 199 ± 13 | 225 ± 20 | 245 ± 25 | 272 ± 12d | 276 ± 25 | 273 ± 21 |

| Alanine | Cirrhotic | 326 ± 23 | 408 ± 41 | 465 ± 48c | 462 ± 12 | 456 ± 29 | 475 ± 47 |

| Citruline | Cirrhotic | 48 ± 7 | 44 ± 7 | 48 ± 7 | 58 ± 5 | 50 ± 7 | 59 ± 10 |

| Valine | Cirrhotic | 146 ± 23 | 160 ± 19 | 185 ± 19 | 209 ± 29c | 224 ± 36 | 243 ± 29 |

| Cysteine | Cirrhotic | 53 ± 3 | 55 ± 4 | 61 ± 7 | 60 ± 4 | 57 ± 3 | 63 ± 4d |

| Methionine | Cirrhotic | 34 ± 4 | 41 ± 4 | 45 ± 4 | 54 ± 6f | 58 ± 6 | 64 ± 8 |

| Isoleucine | Cirrhotic | 43 ± 2 | 57 ± 6 | 63 ± 6d | 86 ± 12 | 97 ± 16 | 107 ± 11 |

| Leucine | Cirrhotic | 73 ± 10 | 93 ± 12 | 107 ± 14 | 135 ± 25c | 149 ± 31 | 160 ± 20 |

| Tyrosine | Cirrhotic | 109 ± 13 | 115 ± 8 | 123 ± 11 | 139 ± 8c | 144 ± 8 | 159 ± 15 |

| Phenylalanine | Cirrhotic | 58 ± 7 | 66 ± 5 | 77 ± 10 | 84 ± 10f | 86 ± 9 | 98 ± 12 |

| Ornithine | Cirrhotic | 62 ± 7 | 69 ± 6 | 73 ± 7 | 81 ± 4f | 90 ± 8 | 94 ± 9 |

| Lysine | Cirrhotic | 148 ± 10 | 179 ± 22 | 211 ± 27c | 240 ± 32 | 248 ± 40 | 253 ± 32 |

| Histidine | Cirrhotic | 68 ± 8 | 80 ± 8 | 89 ± 7 | 90 ± 8 | 91 ± 10 | 93 ± 7 |

| Arginine | Cirrhotic | 91 ± 9 | 99 ± 10 | 109 ± 14 | 134 ± 11c | 139 ± 18 | 152 ± 19 |

| BCAA/AAA | Cirrhotic | 1.69 ± 0.3 | 1.74 ± 0.2 | 1.81 ± 0.2 | 1.93 ± 0.3 | 2.03 ± 0.3c | 2.08 ± 0.4c |

The results are expressed as means ± SEM. Plasma amino acids are given in nmol/mL. First value significantly different from basal value:

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.02.

DISCUSSION

A characteristic pattern of plasma amino acids has been described in cirrhotic subjects[3,4,29-31] and metabolic and biochemical differences have been shown between stable and unstable cirrhotics[3,4,32]. In advanced liver disease there is usually an increased concentration of the AAA tyrosine, phenylalanine and tryptophan, and decreased concentration of the BCAA leucine, isoleucine and valine[3,4,6,9,14]. We have previously reported differences between different stages of liver disease and small or no significant differences between patients with stable liver disease and normal subjects[26]. Plasma amino acid concentrations change in the postabsorptive state reflects the balance between uptake by the liver and release by extrahepatic tissue, primarily muscle[2,3,29,33,34]. Following a mixed meal, the BCAA are transferred from the gut through the liver to peripheral tissues[35]. All other amino acids, including the AAA and methionine, are retained to a greater extent by splanchnic tissues and particularly by the liver[35,36]. The BCAA are then primarily metabolized in extrahepatic tissues i.e. skeletal muscle[28,36].

In most previous studies the methods for patient selection (i.e., disease severity) and nutritional intervention (type and dose of protein or amino acid formula) have varied widely, with very few controlled studies involving a “natural” meal[14,31,35,37]. This precludes the opportunity to make firm interpretations of the metabolic alterations in cirrhotic patients. In the present study we therefore investigated the plasma amino acid response to a natural meal administered to biopsy proven cirrhotic patients (Child-Pugh class A and C).

On the other hand ammonia is a toxic nitrogenous product of protein and amino acid metabolism[38] which under normal circumstances is mainly detoxified by the liver. In patients with cirrhosis there is an increase in circulating ammonia caused by impaired hepatic detoxification and the presence (as in the decompensated cirrhotics group) of porto-systemic shunting[19,39]. Thus the rationale for a protein tolerance test is that if the patient develops HE after the test the risk of developing it after the shunt procedure is likely to be relatively high-information which helps surgeons decide which particular type of porto-systemic shunt or device to perform or use respectively.

Twenty grams protein natural meal

After intake of a mixed meal, there were only small differences for most plasma amino acids between cirrhotic patients and controls (Table 3). Only isoleucine, tyrosine and particularly leucine showed modest, but significantly higher increases in cirrhotic patients after the meal (Table 3 and Figure 2). The mean AAA concentration was also higher, but not significantly so. The higher BCAA and AAA increases observed in cirrhotics may be explained by their peripheral insulin resistance[14] which results in reduced muscle uptake of BCAA and a decreased inhibition of muscle catabolism after food intake. In previous studies, patients at different stages of liver disease were given either a protein load (ranging from 27 to 48 g)[3,14-16,31] or BCAA-enriched formulae[3,9] and showed amino acid “intolerance” to that load of protein or amino acids. The term “intolerance” here being based on a persistent increase of amino acids in plasma[40,41]. It is known, however, that patient selection and factors such as protein type and dosage influence the plasma amino acid response[35,42-44]. Additionally the description “protein intolerant” is better reserved for patients who develop HE during protein intake. The BCAA/AAA ratio, showed a slight but significant decrease 120 min after the meal (Table 3). This is in agreement with previous reports suggesting that this ratio may be useful for detecting differences in amino acid metabolism in different groups of cirrhotics[26,36]. The differences found in our study suggest subtle alterations in the metabolism of BCAA and AAA evident 2 h after a protein meal, although the meal seemed otherwise well tolerated.

In the stable cirrhotic patients we observed a significant increase in the venous plasma ammonia concentration 60 min after food intake (Figure 3) although this protein meal had little effect on alpha amino nitrogen levels (Figure 1). This may be explained by the considerably larger amino nitrogen pool (13.8 mmol N) compared with that of ammonia (0.16 mmol N)[45] which might be more sensitive to cyclic changes in absorptive periods and by protein breakdown in the small intestine[46]. Additionally, a healthy liver has a huge capacity for increasing urea synthesis after protein ingestion, when ammonia is released from the gut into the portal blood. In patients with cirrhosis, liver ammonia clearance is diminished by the decreased functional liver mass, portosystemic shunting and loss of normal perisinusoidal glutamine synthetase activity[47-49]. Nevertheless, the increases in ammonia were modest and most importantly, we did not observe any overt (clinically detectable) HE. The NCT was carried out to test the patients for covert HE which is not clinically detectable. No patients had covert HE after ingestion of the meal. These results support more the role of those factors affecting the clearance of blood ammonia rather than the effect of diet in the development of HE[39].

In this study, the plasma amino acid response to a 20 g natural protein meal was almost the same in cirrhotic patients and controls and we suggest that cirrhotic patients, with a reasonably good liver function have a good tolerance to a natural protein meal. This concurs with current guidelines for protein intake in patients with liver disease[20-22].

High protein meal to decompensated patients with cirrhosis

The baseline results showed that the BCAA/AAA ratio was lower in decompensated cirrhotics than in patients with stable cirrhosis and healthy subjects (Table 4). This characteristic pattern of plasma amino acids has previously been described by us and others[14,26,29,31,34]. In this group administration of a high (1 g/kg body weight) protein meal led to significant increases in most plasma amino acid levels (Figures 2 and 4, Table 4). These results agree in general with those reported by Marchesini et al[14] and by Schulte-Frohlinde et al[31]. The fact that we found slightly lower increases of leucine, methionine, valine, arginine and glycine in our study might be explained by the type of meal administered (balanced and protein of mixed origin vs meat only in other reports)[31,35,43], and by differences in the degree of liver disease in the study populations[14-16]. It is established that a balanced diet increases protein tolerance[43]. Apart from the expected increases in valine and methionine levels, our results showed that tyrosine, leucine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, arginine and glycine were also regularly increased after the meal (Figures 2 and 4, Table 4). We also observed a significant increase in the BCAA/AAA ratio which remained elevated up to three hours. The increment in the BCAA/AAA ratio may have resulted from extreme elevations of the BCAAs included in this ratio, the more advanced degree of the disease and/or a paradoxical tendency to normalization of the BCAA/AAA ratio seen after a high protein dose. This should be further investigated.

Current nutrition guidelines recommend high protein diets (1.2-1.5 g/kg body weight/day) for liver cirrhosis[20-22] but this is mainly based on applied therapeutic interventions rather than on tolerance or challenge tests[20-22,40]. In this study we present experimental evidence supporting those recomendations.

In contrast to the patients with stable cirrhosis, no specific pattern in plasma ammonia concentration was observed in the high protein group (Figure 5), although the concentration in some of the patients reached higher levels than those seen after a standard (20 g) protein meal. The variability of the response in this group suggests an abnormal ammonia metabolism which would be in accordance with the Child-Pugh’s grade of liver insufficiency (i.e., C) and the presence of portal hypertension.

Figure 5.

Plasma ammonia concentrations in cirrhotic patients. Individual results after a 1g/kg per body weight protein meal.

No patients experienced overt HE in spite of the amino acid elevations; only one of the six decompensated cirrhotic patients showed mild electroencephalographic changes compatible with covert HE. Previously, protein loads were thought to be a common precipitating factor for HE[23,27]. However, protein restriction worsens the nutritional status of cirrhotic patients[10,50] and a report by Córdoba et al[49] showed that diets with a normal-high protein content (1.2 g/kg per day) are metabolically more adequate than low-protein diets and can be administered safely to cirrhotic patients with episodic HE. Restriction of dietary protein did not have any beneficial effect[49].

Limitations: We studied a small group of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. As they were following a protocol in preparation for a porto-caval shunt operation a protein tolerance test was done in order to predict the likelihood of the development of HE after the procedure. Those patients represented the high protein meal group in this study. As that was not part of the protocol a control group for this part was not included, although we recognize that it would have given us more complete information and provided a better comparison group than just the standard protein group.

In conclusion, after a natural meal containing 20 g of protein, the overall plasma amino acid response in patients with cirrhosis was similar to that of healthy subjects. Plasma ammonia levels increased slightly but, importantly, no evidence of either covert or overt HE was observed. Patients with decompensated cirrhosis showed higher post-prandial concentrations of amino acids in response to a high protein meal. However, we did not observe any overt HE, hence the obvious benefits of a high protein regime should be considered in these patients[30,50,51]. In this patient group we therefore recommend following the current nutritional guidelines: protein intake of 1.2-1.5 g/kg body weight distributed daily in frequent small meals. If patients develop HE on a high-protein diet, consider supplementation with BCAA[12,13,20].

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ms. Angela Madden for her technical support in the preparation and analysis of the diets. Dr. Campollo O was a fellow of the Programa Universitario de Investigación en Salud (PUIS), UNAM and was supported by a scholarship from DGAPA, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

COMMENTS

Background

The plasma amino acid increase after ingestion of amino acids or protein tends to be associated with an increase in plasma ammonia, which in turn has been implicated in the development of hepatic encephalopathy. There has been long standing discussion over the adequate amount of protein to be administered to patients with liver cirrhosis in spite of generally accepted nutritional guidelines for these patients. Despite current nutrition guidelines recommend high protein diets, recommendations have not been completely adopted in some places where protein restriction is still considered as a general rule and proper dietary management is not readily followed.

Research frontiers

While current nutrition guidelines are mainly based on applied therapeutic interventions there have been few reports investigating the tolerance to dietary protein nor they have studied protein tolerance or challenge tests. In this study the authors investigated the plasma amino acid response to standard and high protein natural meals in patients with liver cirrhosis and looked for evidence of protein intolerance by testing for the presence of either covert or overt hepatic encephalopathy.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Several studies have investigated the effect of protein ingestion on circulating amino acid levels in patients with liver cirrhosis. However, both the type and dosage of protein feed or formula and/or the routes of administration have been varied and the selection of patients has been heterogeneous. The authors aimed to improve on previous methodology by selecting a more homogeneous group of patients with biopsy proven cirrhosis, and by using natural mixed protein meals at two protein levels: A standard (20 g) meal and a high (1 g/kg per body weight) protein meal. In this study they provide experimental evidence to support current nutritional guidelines.

Applications

Current nutritional guidelines recommend normal to high protein diets (1.2-1.5 g/kg body weight/d) which the authors experimented in this study with good results. They did not observe any overt hepatic encephalopathy hence the obvious benefits of a high protein regime. If patients develop hepatic encephalopathy on a high-protein diet, temporary reduction of protein intake and supplementation with branched chain amino acids should be considered.

Terminology

Protein tolerance test: A high protein meal (load) has been used to predict the likelihood of hepatic encephalopathy developing following a porto-caval shunt procedure for the treatment of portal hypertension. Therefore patients are studied before and after ingestion of a high protein meal (1 g protein/kg body weight) and clinical and psychological (i.e., “number connection test“) evaluations are performed to study overt and covert hepatic encephalopathy.

Peer-review

The manuscript is well-structured, the rationale behind the study is clear, and the results are relevant for the field of nutrition in liver disease.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Mexico

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: There are no conflicts of interest arising from this work.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Peer-review started: October 31, 2016

First decision: December 1, 2016

Article in press: April 24, 2017

P- Reviewer: Alonso-Martinez JL, Ruiz-Margain A, Tarantino G S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

References

- 1.Fischer JE, Rosen HM, Ebeid AM, James JH, Keane JM, Soeters PB. The effect of normalization of plasma amino acids on hepatic encephalopathy in man. Surgery. 1976;80:77–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tavill AS. Protein metabolism and the liver. In: Liver and biliary disease, Wright R, Alberti KGMM, Karran S (eds). London, Saunders; 1985. pp. 87–113. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchesini G, Bianchi GP, Vilstrup H, Checchia GA, Patrono D, Zoli M. Plasma clearances of branched-chain amino acids in control subjects and in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1987;4:108–117. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(87)80017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalhan SC, Guo L, Edmison J, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ, Hanson RW, Milburn M. Plasma metabolomic profile in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2011;60:404–413. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato A, Suzuki K. How to select BCAA preparations. Hepatol Res. 2004;30S:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rossi RE, Conte D, Massironi S. Diagnosis and treatment of nutritional deficiencies in alcoholic liver disease: Overview of available evidence and open issues. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:819–825. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douglass A, Al Mardini H, Record C. Amino acid challenge in patients with cirrhosis: a model for the assessment of treatments for hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol. 2001;34:658–664. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shikata N, Maki Y, Nakatsui M, Mori M, Noguchi Y, Yoshida S, Takahashi M, Kondo N, Okamoto M. Determining important regulatory relations of amino acids from dynamic network analysis of plasma amino acids. Amino Acids. 2010;38:179–187. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vilstrup H, Gluud C, Hardt F, Kristensen M, Køhler O, Melgaard B, Dejgaard A, Hansen BA, Krintel JJ, Schütten HJ. Branched chain enriched amino acid versus glucose treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. A double-blind study of 65 patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1990;10:291–296. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(90)90135-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dasarathy S. Treatment to improve nutrition and functional capacity evaluation in liver transplant candidates. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2014;12:242–255. doi: 10.1007/s11938-014-0016-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dam G, Keiding S, Munk OL, Ott P, Buhl M, Vilstrup H, Bak LK, Waagepetersen HS, Schousboe A, Møller N, et al. Branched-chain amino acids increase arterial blood ammonia in spite of enhanced intrinsic muscle ammonia metabolism in patients with cirrhosis and healthy subjects. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;301:G269–G277. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00062.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gluud LL, Dam G, Les I, Córdoba J, Marchesini G, Borre M, Aagaard NK, Vilstrup H. Branched-chain amino acids for people with hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD001939. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001939.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gluud LL, Dam G, Borre M, Les I, Cordoba J, Marchesini G, Aagaard NK, Risum N, Vilstrup H. Oral branched-chain amino acids have a beneficial effect on manifestations of hepatic encephalopathy in a systematic review with meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. J Nutr. 2013;143:1263–1268. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.174375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchesini G, Bianchi G, Zoli M, Dondi C, Forlani G, Melli A, Bua V, Vannini P, Pisi E. Plasma amino acid response to protein ingestion in patients with liver cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1983;85:283–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iob V, Coon WW, Sloan M. Altered clearance of free amino acids from plasma of patients with cirrhosis of the liver. J Surg Res. 1966;6:233–239. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4804(66)80029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Keefe SJ, Ogden J, Ramjee G, Moldawer LL. Short-term effects of an intravenous infusion of a nutrient solution containing amino acids, glucose and insulin on leucine turnover and amino acid metabolism in patients with liver failure. J Hepatol. 1988;6:101–108. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(88)80468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolfe RR. Regulation of muscle protein by amino acids. J Nutr. 2002;132:3219S–3224S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.10.3219S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amodio P, Bemeur C, Butterworth R, Cordoba J, Kato A, Montagnese S, Uribe M, Vilstrup H, Morgan MY. The nutritional management of hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis: International Society for Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism Consensus. Hepatology. 2013;58:325–336. doi: 10.1002/hep.26370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chadalavada R, Sappati Biyyani RS, Maxwell J, Mullen K. Nutrition in hepatic encephalopathy. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010;25:257–264. doi: 10.1177/0884533610368712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plauth M, Cabré E, Riggio O, Assis-Camilo M, Pirlich M, Kondrup J, Ferenci P, Holm E, Vom Dahl S, Müller MJ, et al. ESPEN Guidelines on Enteral Nutrition: Liver disease. Clin Nutr. 2006;25:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plauth M, Schuetz T. Hepatology - Guidelines on Parenteral Nutrition, Chapter 16. Ger Med Sci. 2009;7:Doc12. doi: 10.3205/000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, Cordoba J, Ferenci P, Mullen KD, Weissenborn K, Wong P. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60:715–735. doi: 10.1002/hep.27210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rudman D, Akgun S, Galambos JT, McKinney AS, Cullen AB, Gerron GG, Howard CH. Observations on the nitrogen metabolism of patients with portal cirrhosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1970;23:1203–1211. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/23.9.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sherlock S. Hepatic encephalopathy. In: Sherlock S. Diseases of the liver and biliary system. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific, 1989: 95-115 In: Sherlock S, editor. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guerit JM, Amantini A, Fischer C, Kaplan PW, Mecarelli O, Schnitzler A, Ubiali E, Amodio P. Neurophysiological investigations of hepatic encephalopathy: ISHEN practice guidelines. Liver Int. 2009;29:789–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campollo O, Sprengers D, McIntyre N. The BCAA/AAA ratio of plasma amino acids in three different groups of cirrhotics. Rev Invest Clin. 1992;44:513–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campollo O, MacGillivray BB, McIntyre N. [Association of plasma ammonia and GABA levels and the degree of hepatic encephalopathy] Rev Invest Clin. 1992;44:483–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodwin JF. Spectrophotometric quantitation of plasma and urinary amino nitrogen with fluorodinitrobenzene. Stand Meth Clin Chem. 1970;6:89–98. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dam G, Sørensen M, Buhl M, Sandahl TD, Møller N, Ott P, Vilstrup H. Muscle metabolism and whole blood amino acid profile in patients with liver disease. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2015;75:674–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawaguchi T, Izumi N, Charlton MR, Sata M. Branched-chain amino acids as pharmacological nutrients in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1002/hep.24412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulte-Frohlinde E, Wagenpfeil S, Willis J, Lersch C, Eckel F, Schmid R, Schusdziarra V. Role of meal carbohydrate content for the imbalance of plasma amino acids in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1241–1248. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weber FL, Reiser BJ. Relationship of plasma amino acids to nitrogen balance and portal-systemic encephalopathy in alcoholic liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1982;27:103–110. doi: 10.1007/BF01311702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bianchi G, Marzocchi R, Lorusso C, Ridolfi V, Marchesini G. Nutritional treatment of chronic liver failure. Hepatol Res. 2008;38 Suppl 1:S93–S101. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2008.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tomiya T, Omata M, Fujiwara K. Branched-chain amino acids, hepatocyte growth factor and protein production in the liver. Hepatol Res. 2004;30S:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Capaldo B, Gastaldelli A, Antoniello S, Auletta M, Pardo F, Ciociaro D, Guida R, Ferrannini E, Saccà L. Splanchnic and leg substrate exchange after ingestion of a natural mixed meal in humans. Diabetes. 1999;48:958–966. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.5.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khanna S, Gopalan S. Role of branched-chain amino acids in liver disease: the evidence for and against. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2007;10:297–303. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3280d646b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimomura Y, Honda T, Shiraki M, Murakami T, Sato J, Kobayashi H, Mawatari K, Obayashi M, Harris RA. Branched-chain amino acid catabolism in exercise and liver disease. J Nutr. 2006;136:250S–253S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.1.250S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morgan MY, Blei A, Grüngreiff K, Jalan R, Kircheis G, Marchesini G, Riggio O, Weissenborn K. The treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis. 2007;22:389–405. doi: 10.1007/s11011-007-9060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tarantino G, Citro V, Esposito P, Giaquinto S, de Leone A, Milan G, Tripodi FS, Cirillo M, Lobello R. Blood ammonia levels in liver cirrhosis: a clue for the presence of portosystemic collateral veins. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamberg O, Nielsen K, Vilstrup H. Effects of an increase in protein intake on hepatic efficacy for urea synthesis in healthy subjects and in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 1992;14:237–243. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(92)90164-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vilstrup H. Synthesis of urea after stimulation with amino acids: relation to liver function. Gut. 1980;21:990–995. doi: 10.1136/gut.21.11.990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fleming KE, Wanless IR. Glutamine synthetase expression in activated hepatocyte progenitor cells and loss of hepatocellular expression in congestion and cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2013;33:525–534. doi: 10.1111/liv.12099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morgan MY, Hawley KE, Stambuk D. Amino acid tolerance in cirrhotic patients following oral protein and amino acid loads. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1990;4:183–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1990.tb00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schauder P, Schröder K, Herbertz L, Langer K, Langenbeck U. Evidence for valine intolerance in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1984;4:667–670. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840040417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hussein MA, Young VR, Murray E, Scrimshaw NS. Daily fluctuation of plasma amino acid levels in adult men: effect of dietary tryptophan intake and distribution of meals. J Nutr. 1971;101:61–69. doi: 10.1093/jn/101.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ilan Y, Sobol T, Sasson O, Ashur Y, Berry EM. A balanced 5: 1 carbohydrate: protein diet: a new method for supplementing protein to patients with chronic liver disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:1436–1441. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McCullough AJ, Glamour T. Differences in amino acid kinetics in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1858–1865. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90671-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baker DH. Tolerance for branched-chain amino acids in experimental animals and humans. J Nutr. 2005;135:1585S–1590S. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.6.1585S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Córdoba J, López-Hellín J, Planas M, Sabín P, Sanpedro F, Castro F, Esteban R, Guardia J. Normal protein diet for episodic hepatic encephalopathy: results of a randomized study. J Hepatol. 2004;41:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Plauth M. Restricting protein intake not beneficial. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:502; author reply 502–503. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0502a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawaguchi T, Shiraishi K, Ito T, Suzuki K, Koreeda C, Ohtake T, Iwasa M, Tokumoto Y, Endo R, Kawamura NH, et al. Branched-chain amino acids prevent hepatocarcinogenesis and prolong survival of patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1012–1018.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]