Summary

CD25 is expressed at high levels on regulatory T (Treg) cells and was initially proposed as a target for cancer immunotherapy. However, anti-CD25 antibodies have displayed limited activity against established tumors. We demonstrated that CD25 expression is largely restricted to tumor-infiltrating Treg cells in mice and humans. While existing anti-CD25 antibodies were observed to deplete Treg cells in the periphery, upregulation of the inhibitory Fc gamma receptor (FcγR) IIb at the tumor site prevented intra-tumoral Treg cell depletion, which may underlie the lack of anti-tumor activity previously observed in pre-clinical models. Use of an anti-CD25 antibody with enhanced binding to activating FcγRs led to effective depletion of tumor-infiltrating Treg cells, increased effector to Treg cell ratios, and improved control of established tumors. Combination with anti-programmed cell death protein-1 antibodies promoted complete tumor rejection, demonstrating the relevance of CD25 as a therapeutic target and promising substrate for future combination approaches in immune-oncology.

Keywords: regulatory T cells, CD25, anti-CD25, anti-PD-1, Treg depletion, tumor immunotherapy, Fc gamma receptors, tumor microenvironment, inhibitory Fc receptor

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

CD25 expression is largely restricted to Treg cells in mice and humans

-

•

FcγRIIb inhibits anti-CD25-mediated depletion of intra-tumoral Treg cells

-

•

Fc-optimized anti-CD25 efficiently depletes intra-tumoral Treg cells

-

•

Anti-CD25 synergizes with PD-1 blockade to reject established tumors

Anti-CD25 antibodies have displayed only modest therapeutic activity against established tumors. Arce Vargas et al. demonstrate that existing anti-CD25 antibodies fail to deplete intra-tumoral Treg cells due to upregulation of FcγRIIb within tumors. Fc-optimized anti-CD25 mediates effective depletion of tumor-infiltrating Treg cells and synergizes with PD-1 blockade to promote tumor eradication.

Introduction

Regulatory T (Treg) cells are generally regarded as one of the major obstacles to the successful clinical application of tumor immunotherapy. It has been consistently demonstrated that Treg cells contribute to the early establishment and progression of tumors in murine models and that their absence results in delay of tumor progression (Elpek et al., 2007, Golgher et al., 2002, Jones et al., 2002, Onizuka et al., 1999, Shimizu et al., 1999). In humans, high tumor infiltration by Treg cells and, more importantly, a low ratio of effector T (Teff) cells to Treg cells, is associated with poor outcomes in multiple solid cancers (Shang et al., 2015). Conversely, a high Teff/Treg cell ratio is associated with favorable responses to immunotherapy in both humans and mice (Hodi et al., 2008, Quezada et al., 2006). To date, most studies support the notion that targeting Treg cells, either by depletion or functional modulation, may offer significant therapeutic benefit, particularly in combination with other immune modulatory interventions such as vaccines and checkpoint blockade (Bos et al., 2013, Goding et al., 2013, Quezada et al., 2008, Sutmuller et al., 2001).

Defining appropriate targets for selective interference with Treg cells is therefore a critical step in the development of effective therapies. In this regard, CD25, also known as the interleukin-2 high-affinity receptor alpha chain (IL-2Rα), was the first surface marker used to identify and isolate Treg cells (Sakaguchi et al., 1995) prior to the discovery of their master regulator, transcription factor forkhead box P3 (FoxP3). It is also the most extensively studied target for mediating Treg cell depletion. Whereas CD25 is constitutively expressed on Treg cells and absent on naive Teff cells, transient upregulation has been described upon activation of Teff cells, although these observations derive largely from in vitro studies (Boyman and Sprent, 2012).

A number of pre-clinical studies in mice have used the anti-CD25 antibody clone PC-61 (rat IgG1, λ), which partially depletes Treg cells in the blood and peripheral lymphoid organs (Setiady et al., 2010), inhibits tumor growth, and improves survival when administered before or soon after tumor challenge (Golgher et al., 2002, Jones et al., 2002, Onizuka et al., 1999, Quezada et al., 2008, Shimizu et al., 1999). However, the use of anti-CD25 as a therapeutic intervention against established tumors fails to delay tumor growth or prolong survival (Golgher et al., 2002, Jones et al., 2002, Onizuka et al., 1999, Shimizu et al., 1999). This has been attributed to several factors, including poor T cell infiltration of the tumor (Quezada et al., 2008) and potential depletion of activated effector CD8+ and CD4+ T cells that upregulate CD25 (Onizuka et al., 1999). Early-phase clinical studies exploring the use of vaccines in combination with daclizumab (a humanized IgG1 anti-human CD25 antibody) (Jacobs et al., 2010, Rech et al., 2012) or denileukin difitox (a recombinant fusion protein combining human IL-2 and a fragment of diptheria toxin) (Dannull et al., 2005, Luke et al., 2016) demonstrate a variable impact on the number of circulating Treg cells and vaccine-induced immunity. However, the limited indirect data assessing intra-tumoral FoxP3 transcript levels provide no clear evidence that Treg cells in the tumor microenvironment are effectively reduced and anti-tumor activity has appeared disappointing across all studies, with no demonstrable survival benefit.

The modest therapeutic activity in pre-clinical and clinical settings and concern regarding potential depletion of activated Teff cells has contributed to limited enthusiasm for the further evaluation of anti-CD25 antibodies in combination with novel immunotherapies. However, recent data demonstrate the contribution of intra-tumoral Treg cell depletion to the activity of immune modulatory antibody-based therapies and the relevance of the antibody isotype in this setting (Bulliard et al., 2014, Coe et al., 2010, Selby et al., 2013, Simpson et al., 2013). We therefore re-evaluated CD25 as target for Treg cell depletion and tumor immunotherapy in vivo. We demonstrated that the lack of therapeutic activity of the widely used anti-CD25 antibody (PC-61) against established mouse tumors results from a failure to effectively deplete intra-tumoral Treg cells. Optimizing FcγR binding and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) resulted in superior intra-tumoral Treg cell depletion and potent synergy when combined with programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) blockade. We demonstrated high levels of CD25 expression on Treg but not Teff cells in human tumors, highlighting this receptor as a clinical target and anti-CD25 as a promising therapeutic strategy in combination with novel immunotherapies.

Results

CD25 Is Highly Expressed on Murine Tumor-Infiltrating Treg Cells

We sought to evaluate the relative expression of CD25 on individual T lymphocyte subsets within tumors (TILs) and draining lymph nodes (LNs) of mice 10 days after tumor challenge. CD25 expression appeared consistent across multiple models of transplantable tumor cell lines of variable immunogenicity including MCA205 sarcoma, MC38 colon adenocarcinoma, B16 melanoma, and CT26 colorectal carcinoma, with a higher percentage of CD25-expressing CD4+FoxP3+ Treg cells relative to CD4+FoxP3− and CD8+ Teff cells (Figure 1A). In contrast to in vitro studies, minimal expression of CD25 on the Teff cell compartment was observed in vivo and the percentage of CD25-expressing Teff cells (CD8+ = 3.08%–8.35%, CD4+FoxP3− = 14.11%–26.87%) was significantly lower than on Treg cells (83.66%–90.23%) (p < 0.001) (Figure 1B). CD25 expression was also observed on Treg cells present in LNs and blood (data not shown). However, the level of expression, based on mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), was significantly lower than that observed on tumor-infiltrating Treg cells (Figure 1C). Based on these data, CD25 appeared an attractive target for preferential depletion of Treg cells.

Figure 1.

Anti-CD25-r1-Mediated Depletion of CD25+ Regulatory T Cells Is Restricted to Blood and Lymph Nodes

(A–C) Mouse LNs and TILs were analyzed by flow cytomery 10 days after MCA205 (n = 10), MC38 (n = 5), B16 (n = 3), or CT26 (n = 3) tumor implantation.

(A) CD25 expression on T cell subsets in representative mice. Dotted lines indicate the gate.

(B and C) Percentage (B) and MFI (C) of CD25 in each T cell subset. Error bars show standard error of the mean (SEM). p values obtained by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

(D–G) Tumor-bearing mice were injected with 200 μg of αCD25-r1, αCD25-m2a, or αCTLA-4 on days 5 and 7 after MCA205 tumor implantation. Blood, LNs, and TILs were harvested and processed on day 9 for flow cytometry analysis.

(D) Representative plots showing expression of CD25 (detected with antibody clone 7D4) and FoxP3 in CD3+CD4+ T cells. Numbers show percentage of cells in each quadrant.

(E) MFI of CD25 in CD4+FoxP3+ Treg cells.

(F) Percentage of FoxP3+ Treg cells of total CD3+CD4+ T cells.

(G) CD8+/Treg cell ratios (n = 10). Experiment was repeated three times.

Anti-CD25-Mediated Depletion of Treg Cells Is Limited to Lymph Nodes and Blood

Based on evidence demonstrating the contribution of intra-tumoral Treg cell depletion to the activity of immune modulatory antibodies (Bulliard et al., 2014, Coe et al., 2010, Selby et al., 2013, Simpson et al., 2013), we sought to compare the impact of anti-CD25 (clone PC-61 rat IgG1, αCD25-r1) on the frequency of Teff and Treg cells in the blood, LNs, and TILs of mice with established tumors. We focused our analyses on the MCA205 model because of its higher immunogenicity in order to determine any potential negative impact of αCD25 on activated Teff cells within tumors.

As previously described (Onizuka et al., 1999, Setiady et al., 2010), administration of 200 μg of αCD25-r1 on days 5 and 7 after tumor challenge resulted in a reduced frequency of CD25+ cells in all analyzed sites (Figures 1D and 1E) and a reduction in the frequency of CD4+FoxP3+ Treg cells in blood and LN (Figure 1F). However, αCD25-r1 failed to deplete tumor-infiltrating Treg cells, which demonstrated a CD4+FoxP3+ CD25− phenotype after therapy. Their frequency remained comparable to that of untreated mice (Figure 1F), potentially explaining the lack of efficacy observed against established tumors in previous studies despite an apparent reduction in CD25+ T cells within the tumor (Golgher et al., 2002, Jones et al., 2002, Onizuka et al., 1999, Quezada et al., 2008, Shimizu et al., 1999).

We next investigated whether an antibody with optimized ADCC activity could efficiently deplete intra-tumoral Treg cells without significant impact on Teff cells. We replaced the constant regions of the original αCD25 obtained from clone PC-61 with murine IgG2a and κ constant regions (αCD25-m2a), the classical mouse isotype associated with ADCC, and compared its activity to that of αCD25-r1 in vivo. While both antibody variants resulted in reduced expression of CD25 on T cells and a reduction in the number of Treg cells in blood and LNs, only αCD25-m2a resulted in depletion of tumor-infiltrating Treg cells to levels comparable to those observed with anti-cytotoxic T lymphocyte associated protein-4 (αCTLA-4, clone 9H10), which is known to preferentially deplete Treg cells in the tumor but not the periphery (Figures 1D–1F; Selby et al., 2013, Simpson et al., 2013). In keeping with these observations, both αCD25 isotypes resulted in an increased Teff/Treg cell ratio in circulating lymphocytes and LN, but only αCD25-m2a increased the intra-tumoral ratio in a similar manner to αCTLA-4 (Figure 1G). Despite a reduction in the number of circulating and LN-resident Treg cells, no macroscopic, microscopic, or biochemical evidence of toxicity was observed in the skin, lungs, or liver after multiple doses of αCD25-m2a (Figures S1A–S1C).

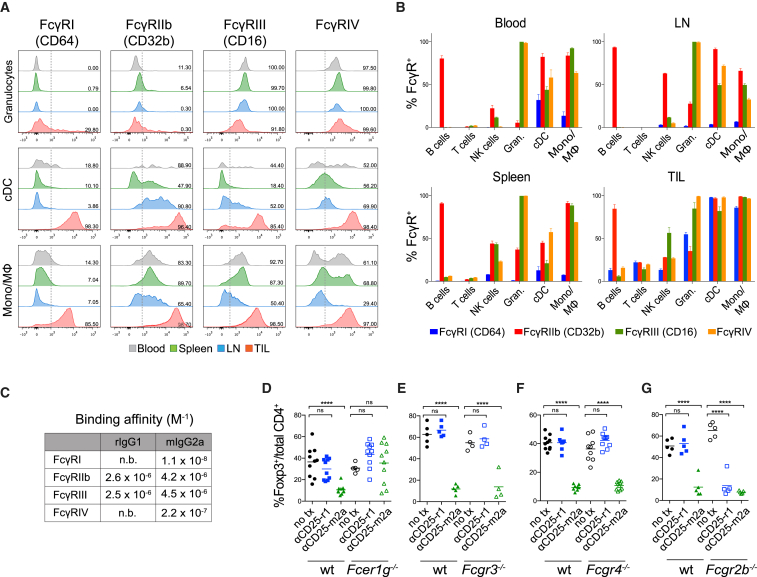

High Expression of FcγRIIb Inhibits αCD25-r1-Mediated Treg Cell Depletion in the Tumor

Anti-CD25-r1 has been described to deplete circulating Treg cells by FcγRIII-mediated ADCC (Setiady et al., 2010). However, its intra-tumoral activity has not been investigated. To determine this, we characterized the expression of Fc-gamma receptors (FcγRs) on different leukocyte subpopulations in the blood, spleen, LN, and tumor of mice bearing MCA205 tumors (Figures 2A and S2). The percentage of FcγR-expressing cells appeared higher on tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells (granulocytic cells, dendritic cells, and monocyte/macrophages) relative to all other studied organs (Figures 2A and 2B). We then analyzed the binding affinity of the two Fc variants of αCD25 to FcγRs (Figure 2C). As previously described (Nimmerjahn and Ravetch, 2005), the mIgG2a isotype binds to all FcγR subtypes with a high activatory to inhibitory ratio (A/I). In contrast, the rIgG1 isotype binds with a similar affinity to a single activatory FcγR, FcγRIII, as well as the inhibitory FcγRIIb, resulting in a low A/I ratio (<1) (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

FcγRIIb Inhibits αCD25-r1-Mediated Treg Cell Depletion in Tumors

(A and B) Expression of FcγRs was measured by flow cytometry in leukocytes from blood, spleen, LNs, and MCA205 tumors (TIL) 10 days after tumor implantation.

(A) Expression of FcγRs on granulocytes (CD11b+Ly6G+), conventional dendritic cells (cDCs) (CD11chiMHC-II+), and monocyte/macrophages (Mono/Mφ) (CD11b+Ly6G−NK1.1−CD11clo/neg). Dotted lines indicate the gate, numbers show the percentage of positive cells.

(B) Cumulative data of FcγR expression in cell subpopulations (n = 3). Error bars represent SEM; the experiment was repeated three times.

(C) Binding affinity of rat IgG1 and mouse IgG2a isotypes to individual mouse FcγRs as determined by surface plasmon resonance (SPR).

(D–G) Percentage of CD4+FoxP3+ Treg cells of total CD4+ T cells in TILs of wild-type (WT, n = 5–10), Fcer1g−/− (n = 10), Fcgr3−/− (n = 5), Fcgr4−/− (n = 10), or Fcgr2b−/− (n = 5) mice treated as in Figures 1D–1G.

To determine which specific FcγRs were involved in αCD25-mediated Treg cell depletion, we quantified the number of tumor-infiltrating Treg cells in mice lacking expression of different FcγRs (Figures 2D–2G). Analysis of Fcer1g−/− mice, which lack expression of activating FcγRs (I, III, and IV), demonstrated a complete absence of Treg cell depletion. Treg cell elimination by αCD25-r1 in the periphery and by αCD25-m2a in the periphery and tumor therefore results from FcγR-mediated ADCC and not blocking of IL-2 binding to CD25 (Figure 2D). Depletion by αCD25-m2a was not dependent on any individual activatory FcγR, with Treg cell elimination maintained in both Fcgr3−/− and Fcgr4−/− mice (Figures 2E and 2F). In keeping with previous studies (Setiady et al., 2010), we confirmed that depletion of peripheral Treg cells by αCD25-r1 depends on FcγRIII (data not shown), but it fails to deplete in the tumor despite high intra-tumoral expression of this receptor (Figure 2E). Intra-tumoral Treg cell depletion was, however, effectively restored in mice lacking expression of the inhibitory receptor FcγRIIb. In this setting, intra-tumoral Treg cell depletion was comparable between αCD25-r1 and αCD25-m2a (Figure 2G). Therefore, the lack of Treg cell depletion by αCD25-r1 in the tumor is explained by its low A/I binding ratio and high intra-tumoral expression of FcγRIIb. FcγRIIb has been associated with modulation of ADCC in tumors (Clynes et al., 2000), and in this case inhibits ADCC mediated by the single activatory receptor engaged by the αCD25-r1 isotype.

Anti-CD25-m2a Synergizes with Anti-PD-1 to Eradicate Established Tumors

To determine whether the enhanced intra-tumoral Treg cell-depleting activity of αCD25-m2a could improve therapeutic outcomes, we compared the anti-tumor activity of αCD25-m2a and -r1 against established tumors. We administered a single dose of αCD25 5 days after subcutaneous implantation of MCA205 cells, when tumors were established with an average diameter of 4–5 mm. Consistent with the observed lack of capacity to deplete intra-tumoral Treg cells (Figure 1F) and previous studies (Golgher et al., 2002, Jones et al., 2002, Onizuka et al., 1999, Quezada et al., 2008, Shimizu et al., 1999), αCD25-r1 failed to control tumor growth. Conversely, growth delay and long-term survival was observed in a proportion of mice receiving αCD25-m2a (15.4%) (Figures 3A and 3B).

Figure 3.

Synergistic Effect of Anti-CD25-m2a and Anti-PD-1 Combination Results in Eradication of Established Tumors

Tumor-bearing mice were treated with 200 μg of αCD25 on day 5 and 100 μg of αPD-1 on days 6, 9, and 12 after tumor implantation.

(A) Growth curves of individual MCA205 tumors, showing the product of three orthogonal tumor diameters. The number of tumor-free survivors is shown in each graph.

(B) Survival of mice shown in (A).

(C and D) Survival of mice with MC38 or CT26 tumors treated as described above (n = 10 per condition).

(E) Percentage of Ki67+ cells in tumor-infiltrating CD4+FoxP3− and CD8+ T cells.

(F) CD4+FoxP3−/CD4+FoxP3+ and CD8+/CD4+FoxP3+ cell ratios.

(G and H) Representative histograms (G) and percentage (H) of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ and CD8+ TILs in MCA205 tumors determined by intracellular staining after ex vivo re-stimulation with PMA and ionomycin. Graphs show cumulative data of two separate experiments (n = 10).

Based on its role in T cell regulation within the tumor microenvironment and the observed clinical activity of agents targeting the PD-1-PD-L1 axis, we hypothesized that depletion of CD25+ Treg cells and PD-1 blockade might be synergistic in combination. In the same model, blocking anti-PD-1 antibody (αPD-1, clone RMP1-14) at a dose of 100 μg every 3 days was ineffective in the treatment of established MCA205 tumors when used as monotherapy or in combination with αCD25-r1 (Figures 3A and 3B). However, a single dose of αCD25-m2a followed by αPD-1 therapy eradicated established tumors in 78.6% of the mice, resulting in long-term survival of more than 100 days (Figures 3A and 3B). This activity was significantly reduced in the absence of CD8+ T cells (Figures S3A and S3B), demonstrating that tumor elimination depends on the impact of the αPD-1 and αCD25 combination on both CD8+ and Treg cell compartments, and that overall effector T cell responses are not negatively impacted by a depleting αCD25 antibody.

Similar findings were observed in MC38 and CT26 tumor models, where αCD25-m2a had a partial therapeutic effect that synergized with αPD-1 therapy (Figures 3C and 3D). Activity was also observed against the poorly immunogenic B16 melanoma tumor model when αCD25-m2a and αPD-1 were combined with a granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-expressing whole tumor cell vaccine (Gvax). As previously described, in this system, Gvax alone failed to extend survival of tumor-bearing mice (Quezada et al., 2006, van Elsas et al., 2001). Combination therapy with αCD25-m2a and αPD-1 translated into a modest increase in survival, which was not observed with αCD25-r1 and αPD-1 (Figure S4).

To understand the mechanisms underpinning the observed synergy, we evaluated the phenotype and function of TILs in MCA205 tumors at the end of the treatment protocol, 24 hr after the third dose of αPD-1 (Figures 3E–3H). Monotherapy with αPD-1 did not impact upon Teff cell proliferation (Figure 3E) nor the number infiltrating the tumor, where a persisting high frequency of Treg cells was observed (data not shown), resulting in a low Teff/Treg ratio (Figure 3F) and lack of therapeutic activity. Conversely, intra-tumoral Treg cell depletion with αCD25-m2a resulted in a higher proportion of proliferating and interferon-γ (IFN-γ)-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the tumor, corresponding to a high Teff/Treg cell ratio and anti-tumor activity (Figures 3E–3H). This effect was further enhanced in combination with αPD-1, which yielded even higher proliferation and a 1.6-fold increase in the number of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells compared to αCD25-m2a alone. In contrast, the observed lack of Treg cell depletion with αCD25-r1 resulted in no change in Teff cell proliferation or IFN-γ production, when used as monotherapy or in combination with αPD-1 (Figures 3E–3H). Combination of αCD25 and αPD-1 therefore appeared highly effective at rejecting established tumors, but only when intra-tumoral Treg cells were efficiently depleted by αCD25 of appropriate isotype.

CD25 Expression Profiles in Human Cancers Validate Its Use as Target for Therapeutic Treg Cell Depletion

To validate the translational value of CD25 as a target for Treg cell depletion, we analyzed the expression of CD25 on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and TILs in patients with advanced melanoma, early-stage non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), and renal cell carcinoma (RCC) by flow cytometry and multiplex immunohistochemistry (IHC). Despite heterogeneity in clinical characteristics both within and between studied cohorts (Tables S1–S3), CD25 expression remained largely restricted to CD4+FoxP3+ Treg cells (mean % CD25+ = 54.8% of Treg, 7.5% of CD4+FoxP3−, and 1.9% of CD8+; p < 0.0001) (Figures 4A and 4B). Similar to murine models, the level of CD25 expression, as assessed by MFI, was significantly higher on CD4+FoxP3+ Treg cells relative to CD4+FoxP3− and CD8+ T cells within all studied tumor subtypes (mean MFI Treg = 190.0, CD4+FoxP3+ = 34.5 and CD8+ = 17.9; p < 0.0001) (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

CD25 Is Highly Expressed on Treg Cell Infiltrating Human Tumors

(A) Representative histograms demonstrating CD25 expression on circulating (PBMC) and tumor-infiltrating (TIL) CD8+, CD4+FoxP3−, and CD4+FoxP3+ T cell subsets. Dotted lines indicate the gate.

(B and C) Quantification of CD25 expression (percentage [B] and MFI [C]) on individual T cell subsets in human melanoma (n = 11), NSCLC (n = 9), and RCC (n = 8). Error bars represent SEM; p values obtained by two-way ANOVA.

(D) Longitudinal analysis of CD25 expression in human melanoma and RCC lesions prior to (“Baseline”) and during PD-1 blockade (“On therapy”). CD8 staining is displayed in red, FoxP3 in blue, and CD25 in brown.

(E) Percentage of CD25 expression on CD8+ and FoxP3+ T cells at baseline and during PD-1 blockade. Plotted values derive from analysis of 10 ×40 high-power fields per patient at each time point.

We further performed longitudinal assessment of CD25 expression in the context of immune modulation. Core biopsies were performed on the same lesion at baseline and after either four cycles of nivolumab (3 mg/kg Q2W) or two cycles of pembrolizumab (200 mg Q3W) in patients with advanced kidney cancer and melanoma, respectively (Table S4). Despite systemic immune modulation, CD25 expression remained restricted to FoxP3+ Treg cells, even in areas of dense CD8+ T cell infiltrate evaluated by multiplex immunohistochemistry (Figures 4D and 4E). These findings confirmed the translational value of the described pre-clinical data, lending further support to the concept of selective therapeutic targeting of Treg cells via CD25 in human cancers.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that CD25 is an attractive target for Treg cell depletion owing to its expression profile on tumor-infiltrating T cells in both mice and humans. Contrary to in vitro studies, minimal expression of CD25 on the effector compartment was observed in vivo. The efficacy of αCD25 as an anti-tumor therapy depends on Treg cell depletion in the tumor microenvironment, which can be achieved only by using an antibody isotype optimized for engagement of activating FcγRs, capable of inducing ADCC. Our results demonstrated that the limited efficacy observed in pre-clinical studies using the αCD25 PC-61 monoclonal antibody with a rat IgG1 isotype relates to ineffective or suboptimal intra-tumoral Treg cell depletion, a consequence of its low A/I binding ratio and high intra-tumoral expression of inhibitory FcγRIIb. This may also explain the modest results observed in early clinical trials using the anti-human CD25 antibody daclizumab. However, the impact of αCD25 antibodies of varying IgG subclass remains to be evaluated in humans.

Local depletion of tumor-infiltrating Treg cells by αCD25 monotherapy mediated only partial tumor control, suggesting that further intervention is necessary to increase the intra-tumoral Teff/Treg cell balance and promote effector T cell activity. These data mirror those previously demonstrated for αCTLA-4 antibodies, where targeting solely the Treg cell compartment was ineffective in eradicating established tumors, while targeting both Treg and Teff cell compartments resulted in effective therapeutic synergy (Peggs et al., 2009). Increased regulation of Teff cell responses by co-inhibitory immune checkpoints in the tumor microenvironment might also explain the modest responses observed in early-stage clinical trials evaluating αCD25 antibodies in cancer patients (Jacobs et al., 2010, Rech et al., 2012). Our data suggest that such responses could be enhanced through combination with therapies that address this regulation including immune checkpoint blockade or agonistic antibodies targeting immune co-stimulatory receptors.

Treg cell depletion can be achieved by targeting other molecules highly expressed on Treg cells (Bulliard et al., 2014, Coe et al., 2010, Selby et al., 2013, Simpson et al., 2013). While combined blocking and depleting activity of specific immune modulatory antibodies is effective against certain target molecules, such as CTLA-4, it can also be deleterious owing to simultaneous high expression on Teff cells. Differential expression is therefore critical; for example, in addition to its expression on Treg cells, PD-1 is highly expressed on activated CD8+ T cells. Anti-PD-1 antibodies therefore lose anti-tumor activity when a depleting antibody isotype is employed (Dahan et al., 2015).

Anti-PD-1 therapy now forms a key part of the treatment paradigm for multiple solid malignancies, with response rates varying between 20% and 30% when used as monotherapy (Topalian et al., 2015). However, the majority of responses are partial. This could be explained in part by tumor infiltration with CD25+FoxP3+ Treg cells that are unaffected by non-depleting αPD-1 antibodies. In this setting another target molecule specific to Treg cells is required in order to achieve potential synergy through Treg cell depletion. Combination of αCTLA-4 and αPD-1 therapy has achieved superior response rates to either agent alone in patients with advanced melanoma (Larkin et al., 2015). This may be the result of the cell-intrinsic immune modulatory activity of αCTLA-4 and αPD-1 antibodies and concomitant depletion of Treg cells by αCTLA-4, although this second activity has not been demonstrated in vivo. Combination therapy results in higher immune-related toxicity, underscoring the need for alternative combinations balancing maximal activity with minimal toxicity. We have demonstrated that αCD25 therapy synergizes with blocking αPD-1 therapy, provided Treg cells are depleted locally in the tumor. Combining αPD-1 with αCD25-depleting antibodies might improve the therapeutic window compared to the αCTLA-4 combination, as αCD25 lacks the additional cell-intrinsic immune modulatory activity of αCTLA-4. Such hypotheses are further supported by our model, in which only transient Treg cell depletion was required for effective synergy, with no evidence of immune-related toxicity. These data support further evaluation of Fc-optimized αCD25 as a combination partner in clinical trials.

Experimental Procedures

Antibodies and Antibody Production

The sequence of the variable regions of the heavy and light chains of αCD25 were resolved from the PC-61.5.3 hybridoma by rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE), cloned into the constant regions of murine IgG2a and κ chains and expressed in a stable K562 cell line generated by co-transduction with murine leukemia virus-derived retroviral vectors encoding both chains. The antibody was initially purified from supernatants with a protein G HiTrap MabSelect column (GE Healthcare), dialyzed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), concentrated, and filter-sterilized. For subsequent experiments, antibody production was outsourced to Evitria AG. Anti-CD25-r1 (PC-61.5.3), αCTLA-4 (9H10), αPD-1 (RMP1-14), and αCD8 (2.43) were supplied by BioXcell. The binding affinity of isotype variants to FcγRs was measured by SPR in the Ravetch laboratory as described before (Nimmerjahn and Ravetch, 2005).

Tumor Experiments

Details of mouse strains, cell lines and flow cytometry antibodies are shown in Supplemental Experimental Procedures. Mice were injected subcutaneously with 5 × 105 MCA205, MC38, or CT26 cells or 5 × 104 B16 cells re-suspended in PBS. Therapeutic antibodies were administered intraperitoneally at the time points and doses shown in figure legends. Cell suspensions for flow cytometry were prepared as described previously (Simpson et al., 2013). Tumors were measured twice weekly and mice were euthanized when any orthogonal tumor diameter reached 150 mm.

Human Study Oversight

Human data derives from three translational studies approved by local institutional review board and Research Ethics Committee (Melanoma, REC no. 11/LO/0003; NSCLC, REC no.13/LO/1546; RCC, REC no. 11/LO/1996). All were conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and with Good Clinical Practice guidelines as defined by the International Conference on Harmonization. All patients (or their legal representatives) provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Analysis of Human Tissue

For flow cytometry, cell suspensions were prepared with the same protocol employed for mouse tissues (Simpson et al., 2013). Leukocytes were enriched by gradient centrifugation with Ficoll-paque (GE Healthcare). Isolated live cells were frozen at −80°C and stored in liquid nitrogen until analysis.

Histopathology protocols are described in Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Data Analysis

Flow cytometry data were analyzed with FlowJo v10.0.8 (Tree Star). Statistical analyses were done with Prism 6 (GraphPad Software); p values were calculated using Kruskall-Wallis and Dunn’s post hoc tests, unless otherwise indicated (ns = p > 0.05; ∗p ≤ 0.05; ∗∗p ≤ 0.01; ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p ≤ 0.0001). Kaplan-Meier curves were analyzed with the log-rank test.

Author Contributions

S.A.Q. and K.S.P. conceived the project. F.A.V., A.J.S.F., K.S.P., and S.A.Q. designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. F.A.V. and A.J.S.F. performed the experiments. I.S., K.J., L.M., M.H.L., A.G., A.S., A.B.A., D.F., M.W.S., Y.N.S.W., and J.Y.H. contributed experimentally. E.M.R., R.D., S.A.B., K.A.C., M.P., and J.V.R. provided reagents and contributed scientifically. T.M. performed the histology analyses. T.O., D.N., B.C., S.T., M.G., J.L., C.S., and the TRACERx consortia coordinated clinical trials and provided patient samples.

Acknowledgments

We thank Josep Linares for his technical expertise. S.A.Q. is a Cancer Research U.K. (CRUK) Senior Fellow (C36463/A22246) and is funded by a Cancer Research Institute Investigator Award and a CRUK Biotherapeutic Program Grant (C36463/A20764). K.S.P. receives funding from the NIHR BTRU for Stem Cells and Immunotherapies (167097), of which he is the Scientific Director. None of the animal work described was funded by NIHR. This work was undertaken at UCL Hospitals/UCL with support from the CRUK-UCL Centre (C416/A18088), CRUK’s Lung Cancer Centre of Excellence (C5759/A20465), the CRUK and Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council at King's College London and UCL (C1519/A16463), the Cancer Immunotherapy Accelerator Award (CITA-CRUK) (C33499/A20265), CRUK’s Lung TRACERx study (led by C. Swanton) (C11496/A17786), the Sam Keen Foundation/RMH NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Bloodwise (formerly Leukaemia and Lymphoma Research) (08022/P4664), the Department of Health, and CRUK funding schemes for National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centres and Experimental Cancer Medicine Centres.

Published: April 11, 2017

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes four figures, four tables, Supplemental Experimental Procedures, and consortia memberships and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2017.03.013.

Contributor Information

Karl S. Peggs, Email: k.peggs@ucl.ac.uk.

Sergio A. Quezada, Email: s.quezada@ucl.ac.uk.

Melanoma TRACERx Consortium:

Lavinia Spain, Andrew Wotherspoon, Nicholas Francis, Myles Smith, Dirk Strauss, and Andrew Hayes

Renal TRACERx Consortium:

Aspasia Soultati, Mark Stares, Lavinia Spain, Joanna Lynch, Nicos Fotiadis, Archana Fernando, Steve Hazell, Ashish Chandra, Lisa Pickering, Sarah Rudman, and Simon Chowdhury

Lung TRACERx Consortium:

Charles Swanton, Mariam Jamal-Hanjani, Selvaraju Veeriah, Seema Shafi, Justyna Czyzewska-Khan, Diana Johnson, Joanne Laycock, Leticia Bosshard-Carter, Gerald Goh, Rachel Rosenthal, Pat Gorman, Nirupa Murugaesu, Robert E. Hynds, Gareth Wilson, Nicolai J. Birkbak, Thomas B.K. Watkins, Nicholas McGranahan, Stuart Horswell, Richard Mitter, Mickael Escudero, Aengus Stewart, Peter Van Loo, Andrew Rowan, Hang Xu, Samra Turajlic, Crispin Hiley, Christopher Abbosh, Jacki Goldman, Richard Kevin Stone, Tamara Denner, Nik Matthews, Greg Elgar, Sophia Ward, Jennifer Biggs, Marta Costa, Sharmin Begum, Ben Phillimore, Tim Chambers, Emma Nye, Sofia Graca, Maise Al Bakir, John A. Hartley, Helen L. Lowe, Javier Herrero, David Lawrence, Martin Hayward, Nikolaos Panagiotopoulos, Shyam Kolvekar, Mary Falzon, Elaine Borg, Celia Simeon, Gemma Hector, Amy Smith, Marie Aranda, Marco Novelli, Dahmane Oukrif, Sam M. Janes, Ricky Thakrar, Martin Forster, Tanya Ahmad, Siow Ming Lee, Dionysis Papadatos-Pastos, Dawn Carnell, Ruheena Mendes, Jeremy George, Neal Navani, Asia Ahmed, Magali Taylor, Junaid Choudhary, Yvonne Summers, Raffaele Califano, Paul Taylor, Rajesh Shah, Piotr Krysiak, Kendadai Rammohan, Eustace Fontaine, Richard Booton, Matthew Evison, Phil Crosbie, Stuart Moss, Faiza Idries, Leena Joseph, Paul Bishop, Anshuman Chaturved, Anne Marie Quinn, Helen Doran, Angela Leek, Phil Harrison, Katrina Moore, Rachael Waddington, Juliette Novasio, Fiona Blackhall, Jane Rogan, Elaine Smith, Caroline Dive, Jonathan Tugwood, Ged Brady, Dominic G. Rothwell, Francesca Chemi, Jackie Pierce, Sakshi Gulati, Babu Naidu, Gerald Langman, Simon Trotter, Mary Bellamy, Hollie Bancroft, Amy Kerr, Salma Kadiri, Joanne Webb, Gary Middleton, Madava Djearaman, Dean Fennell, Jacqui A. Shaw, John Le Quesne, David Moore, Apostolos Nakas, Sridhar Rathinam, William Monteiro, Hilary Marshall, Louise Nelson, Jonathan Bennett, Joan Riley, Lindsay Primrose, Luke Martinson, Girija Anand, Sajid Khan, Anita Amadi, Marianne Nicolson, Keith Kerr, Shirley Palmer, Hardy Remmen, Joy Miller, Keith Buchan, Mahendran Chetty, Lesley Gomersall, Jason Lester, Alison Edwards, Fiona Morgan, Haydn Adams, Helen Davies, Malgorzata Kornaszewska, Richard Attanoos, Sara Lock, Azmina Verjee, Mairead MacKenzie, Maggie Wilcox, Harriet Bell, Natasha Iles, Allan Hackshaw, Yenting Ngai, Sean Smith, Nicole Gower, Christian Ottensmeier, Serena Chee, Benjamin Johnson, Aiman Alzetani, Emily Shaw, Eric Lim, Paulo De Sousa, Monica Tavares Barbosa, Alex Bowman, Simon Jorda, Alexandra Rice, Hilgardt Raubenheimer, Chiara Proli, Maria Elena Cufari, John Carlo Ronquillo, Angela Kwayie, Harshil Bhayani, Morag Hamilton, Yusura Bakar, Natalie Mensah, Lyn Ambrose, Anand Devaraj, Silviu Buderi, Jonathan Finch, Leire Azcarate, Hema Chavan, Sophie Green, Hillaria Mashinga, Andrew G. Nicholson, Kelvin Lau, Michael Sheaff, Peter Schmid, John Conibear, Veni Ezhil, Babikir Ismail, Melanie Irvin-sellers, Vineet Prakash, Peter Russell, Teresa Light, Tracey Horey, Sarah Danson, Jonathan Bury, John Edwards, Jennifer Hill, Sue Matthews, Yota Kitsanta, Kim Suvarna, Patricia Fisher, Allah Dino Keerio, Michael Shackcloth, John Gosney, Pieter Postmus, Sarah Feeney, and Julius Asante-Siaw

Supplemental Information

References

- Bos P.D., Plitas G., Rudra D., Lee S.Y., Rudensky A.Y. Transient regulatory T cell ablation deters oncogene-driven breast cancer and enhances radiotherapy. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:2435–2466. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyman O., Sprent J. The role of interleukin-2 during homeostasis and activation of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012;12:180–190. doi: 10.1038/nri3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulliard Y., Jolicoeur R., Zhang J., Dranoff G., Wilson N.S., Brogdon J.L. OX40 engagement depletes intratumoral Tregs via activating FcγRs, leading to antitumor efficacy. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2014;92:475–480. doi: 10.1038/icb.2014.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clynes R.A., Towers T.L., Presta L.G., Ravetch J.V. Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytotoxicity against tumor targets. Nat. Med. 2000;6:443–446. doi: 10.1038/74704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe D., Begom S., Addey C., White M., Dyson J., Chai J.G. Depletion of regulatory T cells by anti-GITR mAb as a novel mechanism for cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2010;59:1367–1377. doi: 10.1007/s00262-010-0866-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan R., Sega E., Engelhardt J., Selby M., Korman A.J., Ravetch J.V. FcγRs modulate the anti-tumor activity of antibodies targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 axis. Cancer Cell. 2015;28:285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dannull J., Su Z., Rizzieri D., Yang B.K., Coleman D., Yancey D., Zhang A., Dahm P., Chao N., Gilboa E., Vieweg J. Enhancement of vaccine-mediated antitumor immunity in cancer patients after depletion of regulatory T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:3623–3633. doi: 10.1172/JCI25947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elpek K.G., Lacelle C., Singh N.P., Yolcu E.S., Shirwan H. CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells dominate multiple immune evasion mechanisms in early but not late phases of tumor development in a B cell lymphoma model. J. Immunol. 2007;178:6840–6848. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.6840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goding S.R., Wilson K.A., Xie Y., Harris K.M., Baxi A., Akpinarli A., Fulton A., Tamada K., Strome S.E., Antony P.A. Restoring immune function of tumor-specific CD4+ T cells during recurrence of melanoma. J. Immunol. 2013;190:4899–4909. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golgher D., Jones E., Powrie F., Elliott T., Gallimore A. Depletion of CD25+ regulatory cells uncovers immune responses to shared murine tumor rejection antigens. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002;32:3267–3275. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200211)32:11<3267::AID-IMMU3267>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodi F.S., Butler M., Oble D.A., Seiden M.V., Haluska F.G., Kruse A., Macrae S., Nelson M., Canning C., Lowy I. Immunologic and clinical effects of antibody blockade of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 in previously vaccinated cancer patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:3005–3010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712237105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J.F.M., Punt C.J.A., Lesterhuis W.J., Sutmuller R.P.M., Brouwer H.M.-L.H., Scharenborg N.M., Klasen I.S., Hilbrands L.B., Figdor C.G., de Vries I.J.M., Adema G.J. Dendritic cell vaccination in combination with anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody treatment: a phase I/II study in metastatic melanoma patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010;16:5067–5078. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones E., Dahm-Vicker M., Simon A.K., Green A., Powrie F., Cerundolo V., Gallimore A. Depletion of CD25+ regulatory cells results in suppression of melanoma growth and induction of autoreactivity in mice. Cancer Immun. 2002;2:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin J., Chiarion-Sileni V., Gonzalez R., Grob J.J., Cowey C.L., Lao C.D., Schadendorf D., Dummer R., Smylie M., Rutkowski P. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luke J.J., Zha Y., Matijevich K., Gajewski T.F. Single dose denileukin diftitox does not enhance vaccine-induced T cell responses or effectively deplete Tregs in advanced melanoma: immune monitoring and clinical results of a randomized phase II trial. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2016;4:35. doi: 10.1186/s40425-016-0140-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmerjahn F., Ravetch J.V. Divergent immunoglobulin g subclass activity through selective Fc receptor binding. Science. 2005;310:1510–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.1118948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onizuka S., Tawara I., Shimizu J., Sakaguchi S., Fujita T., Nakayama E. Tumor rejection by in vivo administration of anti-CD25 (interleukin-2 receptor alpha) monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3128–3133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peggs K.S., Quezada S.A., Chambers C.A., Korman A.J., Allison J.P. Blockade of CTLA-4 on both effector and regulatory T cell compartments contributes to the antitumor activity of anti-CTLA-4 antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:1717–1725. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quezada S.A., Peggs K.S., Curran M.A., Allison J.P. CTLA4 blockade and GM-CSF combination immunotherapy alters the intratumor balance of effector and regulatory T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:1935–1945. doi: 10.1172/JCI27745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quezada S.A., Peggs K.S., Simpson T.R., Shen Y., Littman D.R., Allison J.P. Limited tumor infiltration by activated T effector cells restricts the therapeutic activity of regulatory T cell depletion against established melanoma. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:2125–2138. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rech A.J., Mick R., Martin S., Recio A., Aqui N.A., Powell D.J., Jr., Colligon T.A., Trosko J.A., Leinbach L.I., Pletcher C.H. CD25 blockade depletes and selectively reprograms regulatory T cells in concert with immunotherapy in cancer patients. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4:134ra62. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi S., Sakaguchi N., Asano M., Itoh M., Toda M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J. Immunol. 1995;155:1151–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby M.J., Engelhardt J.J., Quigley M., Henning K.A., Chen T., Srinivasan M., Korman A.J. Anti-CTLA-4 antibodies of IgG2a isotype enhance antitumor activity through reduction of intratumoral regulatory T cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2013;1:32–42. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setiady Y.Y., Coccia J.A., Park P.U. In vivo depletion of CD4+FOXP3+ Treg cells by the PC61 anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody is mediated by FcgammaRIII+ phagocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 2010;40:780–786. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang B., Liu Y., Jiang S.J., Liu Y. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:15179. doi: 10.1038/srep15179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu J., Yamazaki S., Sakaguchi S. Induction of tumor immunity by removing CD25+CD4+ T cells: a common basis between tumor immunity and autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 1999;163:5211–5218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson T.R., Li F., Montalvo-Ortiz W., Sepulveda M.A., Bergerhoff K., Arce F., Roddie C., Henry J.Y., Yagita H., Wolchok J.D. Fc-dependent depletion of tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells co-defines the efficacy of anti-CTLA-4 therapy against melanoma. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:1695–1710. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutmuller R.P., van Duivenvoorde L.M., van Elsas A., Schumacher T.N., Wildenberg M.E., Allison J.P., Toes R.E., Offringa R., Melief C.J. Synergism of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade and depletion of CD25(+) regulatory T cells in antitumor therapy reveals alternative pathways for suppression of autoreactive cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J. Exp. Med. 2001;194:823–832. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topalian S.L., Drake C.G., Pardoll D.M. Immune checkpoint blockade: a common denominator approach to cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Elsas A., Sutmuller R.P., Hurwitz A.A., Ziskin J., Villasenor J., Medema J.P., Overwijk W.W., Restifo N.P., Melief C.J., Offringa R., Allison J.P. Elucidating the autoimmune and antitumor effector mechanisms of a treatment based on cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 blockade in combination with a B16 melanoma vaccine: comparison of prophylaxis and therapy. J. Exp. Med. 2001;194:481–489. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.