Abstract

Introduction

An approach to radioimmunotherapy (RIT) of metastatic melanoma is the targeting of melanin pigment with monoclonal antibodies to melanin radiolabeled with therapeutic radionuclides. The proof of principle experiments were performed using a melanin-binding antibody 6D2 of IgM isotype radiolabeled with a β emitter 188Re and demonstrated the inhibition of tumor growth. In this study we investigated the efficacy 6D2 antibody radiolabeled with two other longer lived β emitters 90Y and 166Ho in treatment of experimental melanoma, with the objective to find a possible correlation between the efficacy and half-life of the radioisotopes which possess the same high energy β emission properties.

Methods

6D2 was radiolabeled with two other longer lived β emitters 90Y and 166Ho in treatment of experimental melanoma in A2058 melanoma tumor-bearing nude mice, with the objective to find a possible correlation between the efficacy and half-life of the radioisotopes which possess the same high energy β emission properties.

Results

When labeled with the longer lived 90Y radionuclide – the 6D2 mAb did not produce any therapeutic effect in tumor bearing mice and while the slowing down of the tumor growth by 166Ho-6D2 was very similar to the previously reported therapy results for 188Re-6D2. In addition, 166Ho-labeled mAb produced the therapeutic effect on the tumor without any toxic effects while the administration of the 90Y-labeled radioconjugate was toxic to mice with no appreciable anti-tumor effect.

Conclusions

We concluded that it is very important to match the serum half-life of the carrier antibody with the physical half-life of the radionuclide to deliver the tumoricidal absorbed dose to the tumor.

Keywords: Radiotherapy, melanoma, antibody, radioisotopes

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of melanoma is increasing worldwide, with a concomitant rise in mortality from metastatic disease. Patients who progress to stage IV metastatic melanoma (MM) have a median survival of less than 1 year.[1] In the United States, 8,790 deaths from melanoma occurred in 2011 (American Cancer Society, 2013). Until recently, treatment options for patients with stage IV disease were limited and offered marginal, if any, improvement in overall survival. This situation changed with the FDA approval of Yervoy® (anti-CTLA4 monoclonal antibody), an immunomodulator that in a phase III trial was shown to improve overall survival. [2] In addition, Zelboraf® that inhibits mutated B-RAF protein offers hope for 40–60% melanoma patients carrying this mutation.[3,4] However, the responses to the latter have been relatively short-lived and followed by recurrences.

Most melanomas are pigmented by the presence of melanin and many of amelanotic melanomas do contain some melanin. Melanin is an intracellular pigment that is normally found in the melanosome. Melanomas, like many rapidly growing tumors have a large cell turnover resulting in cell lysis and release of pigment. Malignant tumors also contain permeable degenerating cells, which make feasible targeting of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to intracellular antigens. This approach is currently used for detection of prostate cancer, where the intracellular epitope of a prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is targeted with 111In-labeled 7E11 mAb (ProstaScint; Cytogen, Princeton, NJ). Thus, provided such therapies spare other melanotic tissues – melanin presents a promising target for drugs targeting extracellular pigment and carrying a cytotoxic “payload” of radiation capable of killing cells via the “cross-fire” effect. To make “cross-fire” possible, radionuclides with a long β radiation range in tissue are needed.

In vitro studies have demonstrated that the melanin-binding 6D2 mAb bound only to nonviable melanoma cells that had released their melanin or had permeable cell membranes that allowed the mAb access to melanin.5 When treated with 188Re-6D2 mAb – mice with MNT1 human metastatic melanoma tumors showed a marked reduction in tumor volume compared to controls. [5] Detailed mouse biodistribution data showed that the effective half-life of 188Re-6D2 in mice was around 6.5 hrs. [6] The novelty of this approach is that the target, melanin, is an abundant tumor-associated pigment which is very resistant to degradation and persists at the site of the tumor, thus providing more target sites for the targeting molecules with every RIT cycle. Furthermore, since most of the melanin in healthy tissues is intracellular, it is not likely that antibody therapy targeting melanin would harm other pigmented cells such as normal melanocytes or melanin-containing neurons. Recently, 188Re-6D2 has been evaluated in Phase I clinical trials where no adverse effects were observed and in fact, targeted tumors remained stable for several months in more than half of the patients. [7]

The radiolanthanides offer diverse β – energies, penetration depths and half-lives that could be matched with the residence times of antibody and peptide carriers.[8–12] The radiolanthanides also possess imageable γ rays that will facilitate in vivo tracking and calculation of radiation dosimetry. Chelation chemistry varies only in a subtle fashion across the lanthanide series and therefore, to a first approximation, the radiolanthanides are interchangeable in aminocarboxylate ligands, allowing fine tuning of the nuclear properties required for a disease target.[9, 11, 13] This study examines the potential use of Holmium-166 (166Ho) (βmax: 1.8 MeV, t1/2: 27 hrs) and Yttrium-90 (90Y) (βmax: 2.2 MeV, t1/2: 2.7 d) for radiotherapy of melanoma. Both 166Ho and 90Y are hard β emitters with energies close to that of 188Re which was used in our previous RIT of melanoma work. The major difference between these radionuclides is in their physical half-lives with 166Ho half-life of 27 hrs being relatively short while 90Y half-life of 2.7 d is significantly longer thus allowing us to assess the influence of radioisotope half-life on radiotherapy efficacy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and cell lines

Highly pigmented human melanoma cells MNT1 (a kind gift from Dr. V. Hearing, NIH, Bethesda, MD) were grown in MEM/20% FBS medium. Lightly pigmented human melanoma cell line A2058 was purchased from ATCC (Manassass, VA) and grown as described in. [6] The melanin-binding mAb 6D2 (IgM) was produced by Goodwin Biotechnology (Plantation, FL). The IgM UNLB, binding to lipopolysaccharide (clone 11E10, Southern Biotechnology Associates), were used as irrelevant isotype-matched controls.

Reagents

Buffers were made using the highest grade reagents available and using Ultrapure Millipore water to avoid any metal contamination. In addition, all buffers were incubated with 2 grams of CHELEX-100 (Bio-Rad) per liter of buffer for 24 hrs. The Conjugation Buffer, 1M NaHCO3 (10X), was combined with 0.01 M EDTA, pH 8.2. The resulting Conjugation Buffer (10X) was diluted ten fold to obtain the final conjugation buffer (1X). The final EDTA concentration in the buffer was 1 mM and the pH remained 8.2. The Purification Buffer consisted of 0.15 M Ammonium acetate (1X) pH 6. The Saline Purification Buffer consisted of 0.15 M Ammonium acetate (1X) + 0.4 NaCl, pH 6. This buffer was incubated with CHELEX-100 for 48 hrs. CHX-A″ DTPA was purchased from Macrocyclics Inc (Dallas, TX).

Radionuclides

90Y was purchased from MDS Nordion (Fleurus, Belgium) as 90YCl3 in 0.04 N HCl with 31,822 MBq/mL specific activity. High Specific activity 166Ho was produced at the University of Missouri Research Reactor (MURR) from the neutron irradiation of 1 mg of isotopically enriched 164Dy to produce 166Dy which β decays to 166Ho. As “cold” 165Ho is produced as well – an initial separation is performed by absorption chromatography at the end of the irradiation to isolate the 166Dy from the 165Ho. The 166Dy is then allowed to decay for 40 hrs to produce the no carrier added 166Ho which is then separated by absorption chromatography. The final product was concentrated and redissolved with 0.05 M HCl.

Protein Conjugation to CHX-A″ DTPA

6D2 antibody at 4.9 mg/mL or IgM UNLB antibody at 1 mg/mL (volume up to 0.1mL) was transferred to dialysis tubing (Slide-A-Lyzer MINI Dialysis Units, 20K MWCO, Thermo Scientific, IL) and was dialyzed against 1X conjugation buffer (1 L) for 2 hrs at room temperature. The protein solution was transferred to a metal free 2.0-mL Eppendorf tube and CHX-A″ DTPA (approx. 1 mg/1mL) in conjugation buffer was added to the protein solution. The volumes of CHX-A″ DTPA added were adjusted to vary the CHX-A″ DTPA / protein ratios. The reaction mixture was allowed to stand at room temperature overnight (18 hrs). The mixture was then transferred to Centricon-50 filtration units. Saline purification buffer was added to give a final volume of 1.5 mL and then centrifuged at 3,000 RPM to approximately 0.2 mL. The purification procedure was repeated 6 times. The samples (~200 μL) were transferred to dialysis tubing (Slide-A-Lyzer MINI Dialysis Units, 20K MWCO) and were dialyzed against purification buffer (1 L) for 2 hrs at room temperature to obtain the samples free of NaCl. The concentration of the CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 antibody construct was measured using Bradford assay[14] and the total protein recovery was always higher than 80%. The average number of chelators per antibody was determined by the yttrium-arzenazo III spectrophotometric method. [15] Inmunoreactivity of the CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 was measured by melanin ELISA, performed as in. [6]

Radiolabeling procedure

For radiolabeling with 90Y 203.5 MBq (5.5 mCi) in 0.04 M HCl was added to 1.1 mg of CHX-A″ DTPA-6D2 in ammonium acetate buffer. The solution was gently mixed and allowed to incubate at 37°C for 60 min, after which 0.1 mol/L EDTA was added to the tube (50 μL) to chelate any free radiometal. The radiolabeling yield was measured by silica gel instant thin layer chromatography (SG ITLC) developed in ammonium acetate. In this system, radiometal EDTA complex moves with the solvent front while radiolabeled protein stays at the application point. The strips were cut into 2 equal segments and the radioactivity of each segment was counted in a γ counter (Wallac, Finland).

For radiolabeling with 166Ho, 200 μL of 166Ho (100 MBq (2.7 mCi)/0.5 mL in 0.05M HCl) was added to 250 μg of CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 antibody conjugate (500 μL, 0.5 mg/mL) in purification buffer (pH 6). The solution was gently mixed and allowed to incubate at 37°C for 60 min, after which 50 μL of 0.1 mol/L EDTA was added to chelate any free radiometal. The resulting solution was incubated for 25 min after which ITLC assay revealed that the radiolabeling yield was above 80%. The ITLC for 166Ho- CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 was performed using cellulose (Whatman 3MMCHR) strips and a mobile phase of 60% ethanol, 40% water using a BioScan 2000. Under these conditions, the 166Ho-EDTA elutes at the solvent front and 166Ho- CHX-A″ DTPA –6D2 remains at the origin. For in vitro cell binding studies and biodistribution, the 166Ho- CHX-A″ DTPA –6D2 mAb was purified from free 166Ho using HiTrap desalting column (GE HealthCare, Pittsburg, PA). First, the column was washed with 25 mL purification buffer (pH 6). Next, the sample was introduced to the column and purification buffer was used to elute the sample off the column. 166Ho- CHX-A″ DTPA –6D2 was identified by ITLC assay and used in further experiments.

In vitro serum stability studies

The in vitro stability of 166Ho- CHX-A″ DTPA –6D2 was performed by incubating the complex with fetal bovine serum (a kind gift of the Foster Lab at Hunter College, NY) at 37°C. At various time points (0 and 12 hrs) aliquots were taken and analyzed by HPLC using Pharmacia Superose 12 HR 10/30 column (mobile phase was 100 mM sodium phosphate/0.05% sodium azide 1mL/min pH 6.2). The detection was performed using on-line UV detector (Agilent) and radioactivity detector (home-built). The antibody peak eluted at 7.8 min.

Cell lines and in vitro binding experiments

The binding of the 166Ho- CHX-A″ DTPA –6D2 to highly pigmented human melanoma MNT1 cells was evaluated by incubating 40 ng/mL of the radiolabeled mAb with 0.25–2.0 × 106 osmotically lysed cells. After incubation for 1 hr at 37°C with gentle shaking the cells were collected by centrifugation, the supernatant was removed, the cell pellet washed with PBS, and the pellet and the supernatant were counted in a γ counter to calculate the percentage of antibody binding to the cells. As a control for proving the specificity of 166Ho- CHX-A″ DTPA –6D2 binding, the MNT1 cells were also pre-incubated with an excess (50 μg/mL) of “cold” 6D2 for 1 hr before the addition of 166Ho- CHX-A″ DTPA –6D2.

Biodistribution of 166Ho-CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 in A2058 melanoma tumor-bearing nude mice

All animal studies were carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Institute for Animal Studies at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Four six-eight week old female nude mice BALB/c were implanted subcutaneously into the right flank with 8 × 106 A2058 human metastatic melanoma cells and used for the biodistribution after 10 days, when the tumor volumes reached on average 0.15 cm3 (0.02–0.4 cm3). In order to increase the amount of 6D2 per mouse to 100 μg to match the results with 188Re-6D2 described in [6] – 275 μL (1.35 mg) 6D2 was added to Sample 4. Mice were injected IV with 1.85 MBq (50 μCi) 166Ho-CHX-A″ DTPA –6D2 in 100 μL volume and the biodistribution was performed 2 hrs later.

Comparative therapy studies in tumor bearing mice

For the therapy study, A2058 tumor-bearing mice (5 mice per group) with tumors of the size described above were treated with 3 different activities of 90Y-CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 – 4.625, 9.25 and 18.5 MBq (0.125, 0.250 and 0.5 mCi) with values being selected based on the literature data describing 90Y-labeled IgGs in experimental RIT of cancer 16,17 as no 90Y-labeled IgM data was found), or with 37 MBq (1.0 mCi) 166Ho-CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 or given PBS IP. Tumor sizes were measured weekly for 4 weeks and the results were compared with 188Re-6D2 data. [6]

Dosimetry calculations

To calculate the doses to the tumors and normal organs for 166Ho- CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 and 188Re-6D2 the full published biodistribution data was reported in[6] was utilized for calculations. The model[19] which we used in this paper extended the general model developed by Hui18 beyond 90Y to 188Re, 166Ho, 149Pm, 64Cu and 177Lu using two Monte Carlo radiation transport codes, MCNP4C and PEREGRINE, to solve the radiation transport problem. Both transport codes utilize the Monte Carlo methodology, but MCNP4C’s geometry is typically defined by combinations of simple geometrical shapes whereas PEREGRINE is voxel-based. Absorbed fractions in the liver, spleen, kidneys, lungs, heart, stomach, small and large bowel, thyroid, pancreas, bone, marrow (femur), and the whole body were estimated. Additionally, absorbed fraction values were determined for a range of tumor sizes. For tumors, a geometrical model is employed which more accurately reflects the tumors that are grown on the flanks of mice. This geometry simulates the tumors as spheres half embedded in the carcass of the mouse while the top half is protruding above the carcass surface and is covered by 0.5 mm of skin. These absorbed fractions, along with isotope specific isotope properties (yield, average Β energy, etc.) were used to develop MIRD-type tables with units of mGy/MBq-sec for all possible combinations of source and target organs. Once the total number of decays (MBq-sec) in source organs are estimated from laboratory data, the doses to all target organs can be calculated by simple matrix multiplication.

RESULTS

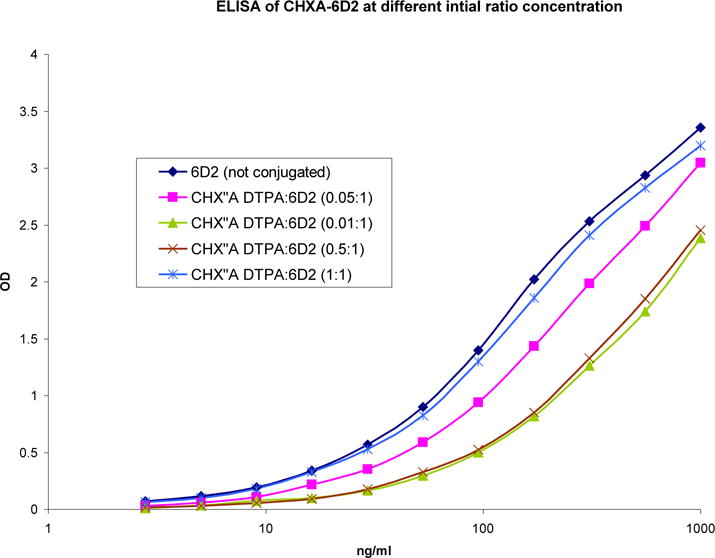

Immunoreactivity of CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2

The immunoreactivity of CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 constructs as a function of initial ratio, from 0.01:1 to 1:1, was determined. The results are illustrated in Figure 1. The immunoreactivity of the construct appeared to be independent of the initial ratios of the ligand to 6D2 mAb in the 0.01–1 range. At the ratio of 1:1 the immunoreactivity was preserved and this initial ratio was chosen for further experiments. The final ratio of ligand conjugated to the 6D2 antibody, determined using yttrium-arzenazo III spectrophotometric method, [15] was found to be 0.2:1 (ligand to antibody).

Figure 1.

Immunoreactivity of complex CHX-A″ DTPA -6D2 antibody as a function of varying the initial ratios of CHX-A″ DTPA to 6D2 antibody.

Radiolabeling

For 90Y the radiolabeling yield was >95% and no radiolabeled product purification was required. For 166Ho specific activities of 74 MBq (2 mCi)/mg and 148 MBg (4 mCi)/mg CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2, the radiolabeling yields were generally above 90%. At higher specific activities of 296 and 370 MBq (8 mCi and 10 mCi)/mg CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2, the radiolabeling yields were lower, 80% and 13%, respectively. For in vitro and in vivo studies, the specific activity of 159 MBq (4.3 mCi)/mg was employed.

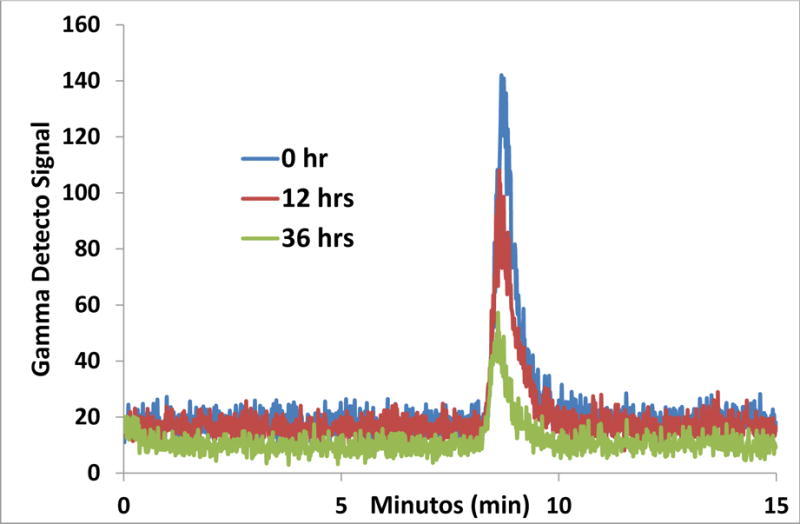

Stability in serum and in vitro binding to MNT1 cells

After the initial best ratios were chosen based on the immunoreactivity studies above, the CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 construct was radiolabeled with 166Ho; the specific activity was determined to be 159 MBq (4.3 mCi)/mg of protein. The radiolabeling with 90Y resulted in 5 mCi/mg specific activity of the protein. The serum stability of the 166Ho- CHX-A″ DTPA-6D2 antibody was examined in serum fetal bovine at 37°C. Aliquots were taken initially and at 12 hrs and analyzed by HPLC. The antibody peak eluted at 7.8 min. The integrity of the radiolabeled antibody was conserved after 12 hr incubation at 37° C (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

166Ho- CHX-A″ DTPA -6D2 antibody serum stability at 0 and 12 hrs. The 166Ho-CHX”ADTPA-6D2 mAb elutes at 7.8 min.

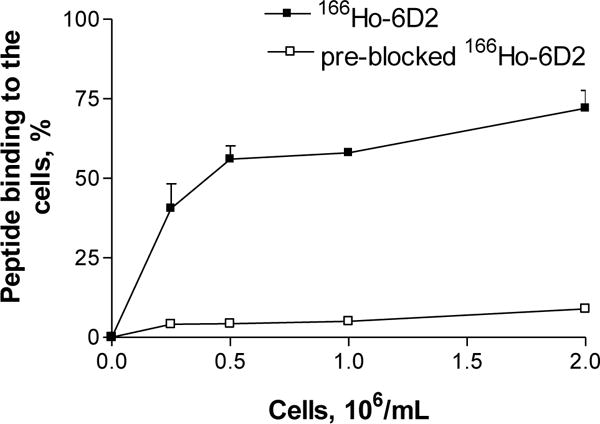

The in vitro melanin-binding properties were examined by evaluation of the binding of radiolabeled 6D2 to MNT1 cells. Since melanin is available for binding outside of the cells, the MNT1 cells were osmotically lysed and further release of melanin was induced. To accomplish the blocking experiment, the 6D2 antibody was added to the cells prior to the addition of the radiolabeled 166Ho-CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2. The results presented in Figure 3 demonstrate the specific binding of 166Ho- CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 to melanin released from the melanoma cells.

Figure 3.

In vitro binding of 166Ho- CHX-A″ DTPA -6D2 to MNT1 human melanoma cells. The blocked MNT1 samples were incubated with 6D2 antibody prior to incubation with 166Ho- CHX-A″ DTPA -6D2.

Biodistribution studies

The biodistribution of the 166Ho-CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 was compared to that of 188Re-6D2, previously reported by our group. [6] The tumor localization for 166Ho-CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 at 2 hrs post injection was quite similar to that of 188Re-6D2 while clearance of 166Ho-CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 from the major organs much faster than 188Re-6D2. The data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Biodistribution of the 166Ho-CHX”ADTPA-6D2 mAb in A2058 tumor bearing mice.

| Organ | Injected dose per gram, % ± SD

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 166Ho CHX”A 6D2 | 188Re-6D26 | |

| Blood | 0.35 ± 0.15 | 20.56 ± 7.00 |

| Lungs | 0.27 ± 0.21 | 4.54 ± 0.80 |

| Heart | 0.64 ± 0.28 | 1.85 ± 0.40 |

| Spleen | 0.49 ± 0.36 | 8.42 ± 2.00 |

| Liver | 0.91 ± 1.03 | 8.46 ± 3.20 |

| Kidney | 3.28 ± 0.74 | 12.90 ± 4.20 |

| Bone/Marrow | 0.70 ± 0.52 | 4.50 ± 1.20 |

| Tumor | 0.97 ± 0.80 | 1.33 ± 0.50 |

| Muscle | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.02 ± 0.00 |

In vivo radiotherapy studies

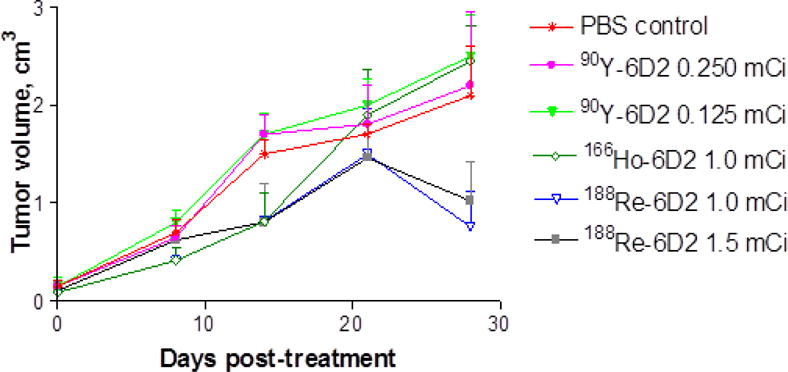

The therapeutic effects of 166Ho-CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 were compared to those of 90Y-CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 in A2058 tumor bearing mice. Furthermore, the results were compared with those from the published 188Re-6D2 study in the same tumor model6 (Figure 4). 90Y-CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2, at activities of 4.625 and 9.25 MBq, did not produce any therapeutic effect in comparison with PBS treated controls while 18.5 MBq 90Y-CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 dose was toxic with all mice in that group dying by Day 14 (not shown on the graph). Thirty seven MBq 166Ho-CHX-A″ DTPA–6D2 produced some slowing down of the tumor growth for 14 days post-injection and then the tumor growth in that group equalized with the controls. This effect on the tumor was very similar to that of 37 MBq of 188Re-6D2 with the only statistically significant difference between two agents observed on Day 28 of observation period (P<0.05).

Figure 4.

Therapy of A2058 tumor bearing mice with 166Ho- CHX-A″ DTPA -6D2 and 90Y- CHX-A″ DTPA 6D2. The 188Re-6D2 therapy data from 6 is also included into the graph for comparative purposes.

Dosimetry to the tumor and organs

The dosimetry results for 166Ho-CHX-A″ DTPA –6D2 and 188Re-6D2 are shown in Table 2. Due to the comparable β energies and relatively close physical half-lives – the total doses to the tumor and the organs were very similar for both radionuclides.

Table 2.

Dosimetry calculations for the 166Ho-CHX”ADTPA-6D2 and 188Re-6D2 mAbs in A2058 tumor bearing mice.

| Organs | Organ self dose, mGy/mCi

|

Dose from other organs, mGy/mCi

|

Total dose, mGy/mCi

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 166Ho | 188Re | 166Ho | 188Re | 166Ho | 188Re | |

| Liver | 13,855 | 12,953 | 1260 | 1186 | 15,115 | 14,139 |

| Spleen | 8586 | 7723 | 4924 | 4625 | 13,510 | 12,348 |

| Kidney | 21,816 | 20,321 | 2111 | 1955 | 23,927 | 22,275 |

| Lungs | 3319 | 3275 | 9636 | 9019 | 12,955 | 12,294 |

| Heart | 3655 | 3237 | 2618 | 2528 | 6273 | 5765 |

| Stomach | 4874 | 4731 | 7518 | 6919 | 12,392 | 11,650 |

| L. Bowel | 1487 | 1423 | 1680 | 1572 | 3167 | 2995 |

| Tumor | 1959 | 1835 | 148 | 143 | 2108 | 1979 |

| Bone | 1833 | 1709 | 3869 | 3558 | 5702 | 5267 |

| Marrow | 23,163 | 21,286 | 7976 | 7436 | 31,139 | 28,722 |

| Blood | 7914 | 7719 | 4394 | 4071 | 12,308 | 11,791 |

| Muscle | 99 | 83 | 4220 | 4022 | 4319 | 4106 |

DISCUSSION

RIT emerged as an alternative treatment modality to chemotherapy and external beam radiation therapy almost 3 decades ago. In 2003–04 FDA approved two radiolabeled monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to CD20 antigen Zevalin® and Bexxar® (labeled with 90Y and 131I, respectively) for the treatment of relapsed or refractory B-cell NHL as a single shot. As a result of its clinical success, Zevalin® was approved by FDA as part of first line therapy for Non-Hodgkins Lymphoma (NHL) and demonstrates the potential of RIT as an anti-neoplastic strategy.

Several years ago our group suggested targeting melanin, which gives melanoma its name, with a radiolabeled mAb to melanin for treatment of metastatic melanoma. [5,6] We demonstrated the feasibility of targeting melanin released from melanoma cells in tumors with melanin-binding mAb 6D2 labeled with β-emitting radionuclide 188Re (188Re). That approach was taken into the clinic for a Phase Ia/Ib clinical trial in patients with metastatic melanoma and shown to be safe as well as resulted in tumor stabilization and prolongation of survival in some patients. [7]

In general, radiopharmaceutical development based on radioactive rhenium (188Re) is scant in comparison with radiolanthanides such as 177Lu. The reasons for this is the lack of a stable in vivo 188Re chelate that does not allow the oxidation to perrhenate (188ReO4−, Re(VII)). Along with the lack of stable chelate technology, there are no convenient, efficient methods to introduce 188Re into mAbs. Presently “direct labeling” (i.e., reduction of the mAb disulfide bonds) followed by reduction of 188ReO4− and incorporation of reduced 188Re into the disulfide bonds, is the only viable method for radiolabeling antibodies with 188Re and the melanin-targeting mAbs were labeled in this fashion. This method has acknowledged major limitations, [20] including in vivo instability of the conjugates and compromised immunogenicity of the mAb due to the labeling procedure. This is why it is important to investigate the potential of other strong β emitters for radiolabeling of mAbs for melanoma therapy.

This study examines the potential use of Holmium-166 (166Ho) (βmax: 1.8 MeV, t1/2: 27 hrs) and Yttrium-90 (90Y) (βmax: 2.2 MeV, t1/2: 2.7 d) for radiotherapy of melanoma. There are many advantages to these isotopes and the radiolanthanides in general. These include ease of conjugation of the bifunctional ligand, CHX-A″ DTPA – benzyl isothiocyanate can be conjugated to the 6D2 antibody with retention of immunoreactivity. Another advantage is that the radiolabeling procedure is relatively quick and facile compared to direct labeling necessary for 188Re (βmax: 2.20 MeV, t1/2: 16.7 hrs). The use of no carrier added 166Ho was specifically chosen as the closest match to the half-life of 188Re. Also, importantly, the bifunctional chelate chemistry for linking radiolanthanides to antibodies is mature. Moreover, 90Y and 166Ho are stable in the CHX-A″ DTPA chelate. The isotopes chosen possess energies and half-lives that encompass those of 188Re and this study allows us to evaluate the effect of energy and half-life on therapy of melanoma using the 6D2 antibody. 166Ho possesses a lower β− energy and range in tissue than 188Re with a slightly longer half-life. 90Y possesses similar β− energy but a much longer half-life.

Conjugation of the bifunctional ligand did not compromise the immunoreactivity of the resulting construct towards melanin. The development of high specific activity radiolanthanides is key to the development of lanthanide-based radiopharmaceuticals for RIT. The CHX-A″ DTPA-6D2 antibody construct was labeled with no carrier added 166 Ho with a specific activity of 148 MBq/mg of protein using standard techniques with the radiolabeling yields being greater than 80%. The serum stability of the 166Ho-CHX-A″ DTPA-6D2 antibody, chosen as a representative for the radiolanthanides and 90Y, suggests that the complex remains intact in serum: similar HPLC profiles at the initial time and at 12 hrs incubation were obtained. In vitro binding showed that the percentage of in vitro binding of 166Ho-CHX-A″ DTPA-6D2 to MNT1 cells increased with an escalating concentration of cells suggesting specific binding to MNT1 cells. Blocking with 6D2 antibody decreased the binding of 166Ho-CHX-A″ DTPA-6D2 10-fold which serves as additional proof of the specificity of 166Ho-CHX-A″ DTPA-6D2 binding to MNT1 melanoma cells.

The biodistribution of the 166Ho-CHX-A″ DTPA-6D2 was performed for comparison with the 188Re-6D2, previously reported by Dadachova et al.[5,6] The tumor localization for 166Ho-CHX-A″ DTPA-6D2 and for 188Re-6D2, being around 1% ID/g at 2 hrs post injection, was similar. This observation, when taken together with the almost identical radiation doses to the tumors and the major organs derived from the dosimetric calculations, supports the use of 166Ho as a potentially suitable radiotherapeutic nuclide for melanoma therapy.

The therapeutic effect of 166Ho-CHX-A″ DTPA-6D2 and 90Y-CHX-A″ DTPA-6D2 was studied in mice bearing tumors similar to the previously reported data for 188Re-6D2. [6] Since the three radioisotopes have different half-lifes, the importance of the half-life versus the clearance of the antibody from the body could be addressed and analyzed. When labeled with the longer lived 90Y radionuclide – the 6D2 mAb did not produce any therapeutic effect in tumor bearing mice while reduced the tumor growth by 166Ho- CHX-A″ DTPA-6D2 was very similar to the previously reported therapy results for 188Re-6D2. [6] Carrier, protein clearance, the radionuclide half-life and the residence time of the radiolabeled protein in the tumor should be considered for the choice of radionuclide and antibody combinations for optimal therapeutic efficiency. The biodistribution of 188Re-6D2 was characterized by fast blood clearance with a half-life of 6.5 hrs. This is in good agreement with the short half-lives of IgMs that may be completely cleared from the blood in 24 hrs. The rapid pharmacokinetics of the 6D2 antibody appears well matched with the shorter half-live radionuclides. As the residence time of 6D2 in the tumor is short, shorter lived radionuclides such as 166Ho and 188Re can deliver much higher absorbed dose to the tumor when compared to long lived 90Y, resulting in a measurable therapeutic effect.

CONCLUSIONS

We have radiolabeled melanin binding mAb 6D2 with a short-lived radiolanthanide 166Ho and with longer lived 90Y and investigated the potential of these radioconjugates in experimental melanoma therapy. 166Ho-labeled mAb to melanin produced some therapeutic effect on the tumor without any toxic effects while the administration of the 90Y-labeled radioconjugate was toxic to mice with no appreciable anti-tumor effect. We concluded that it is very important to match the serum half-life of the carrier antibody with the physical half-life of the radionuclide to deliver the tumoricidal absorbed dose to the tumor.

Footnotes

All authors of this manuscript do not have institutional or commercial affiliations that might pose a conflict of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript. E. Dadachova is a co-inventor on the granted US patent on RIT of melanoma with melanin-binding antibodies.

References

- 1.Linos E, Swetter SM, Cockburn MG, Colditz GA, Clarke CA. Increasing Burden of Melanoma in the United States. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2009;129:1666–1674. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C. Phase III randomized, open-label, multicenter trial (BRIM3) comparing BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib with dacarbazine (DTIC) in patients with V600EBRAF-mutated melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl) abstr LBA4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ribas A, Kim AB, Schuchter LM. BRIM-2: An open-label, multicenter phase II study of vemurafenib in previously treated patients with BRAF V600E mutation-positive metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(suppl) abstr 8509. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dadachova E, Nosanchuk JD, Shi L, Schweitzer AD, Frenkel A, Nosanchuk JS. Dead cells in melanoma tumors provide abundant antigen for targeted delivery of ionizing radiation by a mAb to melanin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:14865–14870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406180101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dadachova E, Revskaya E, Sesay MA, Damania H, Boucher R, Sellers RS. Pre-clinical evaluation and efficacy studies of a melanin-binding IgM antibody labeled with 188Re against experimental human metastatic melanoma in nude mice. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1116–1127. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.7.6197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein MM, Lotem T, Peretz ST, Zwas S, Mizrachi Y, Liberman R, et al. Safety and efficacy of 188-Rhenium-labeled antibody to melanin in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Skin Cancer. 2013;828329 doi: 10.1155/2013/828329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miao Y, Quinn TP. Peptide-targeted radionuclide therapy for melanoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;67:213–28. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohsin H, Jia F, Sivaguru G, Hudson MJ, Shelton TD, Hoffman TJ, et al. Radiolanthanide-labeled monoclonal antibody CC49 for radioimmunotherapy of cancer: biological comparison of DOTA conjugates of 149Pm, 166Ho, 177Lu. Bioconj Chem. 2006;17 doi: 10.1021/bc0502356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewis M, Zhang J, Jia F, Owen NK, Cutler CS. Biological comparison of 149Pm-, 166Ho-, and 177Lu-DOTA-biotin pretargeted by CC49 scFv-streptavidin fusion protein in xenograft-bearing nude mice. Nucl Med Biol. 2004;31:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Capello A, Krenning E, Breeman WA, Bernard BF, Konijnenbert MW, deJong M. Tyr3-Octreotide and Tyr3-Octreotate Radiolabeled with 177Lu or 90Y: Peptide Receptor Radionuclide Therapy Results In Vitro. Cancer Biotherapy & Radiopharmaceuticals. 2003;18:761–768. doi: 10.1089/108497803770418300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohsin H, Sivaguru G, Jia F, Bryan JC, Cutler CS, Ketring AR. Comparison of pretarget and conventional CC49 radioimmunotherapy using 149Pm, 166Ho and 177Lu. J Labelled Compds Radiopharm. 2005;48 doi: 10.1021/bc200258x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu F, Cutler CS, Hoffman T, Sieckman G, Volkert WA, Jurisson SS. Pm-149 DOTA bombesin analogs for potential radiotherapy in vivo comparison with Sm-153 and Lu-177 labeled DO3A-amide-bAla-BBN(7-14)NH2. Nucl Med Biol. 2002;29:423–430. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(02)00290-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noble JE, Bailey MJA. QUANTITATION OF PROTEIN. In: Burgess RR, Deutscher MP, editors. Guide to Protein Purification. Second. Vol. 463. Elsevier Academic Press Inc; San Diego: 2009. pp. 73–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pippen CG, Parker TA, McMurry TJ, Brechiel MW. Spectrophotometric method for the determination of a bifunctional DTPA ligand in DTPA-monoclonal antibody conjugates. Bioconj Chem. 1992;3:342–344. doi: 10.1021/bc00016a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karacay H, Sharkey RM, Gold DV, Ragland DR, McBride WJ, Rossi EA. Pretargeted radioimmunotherapy of pancreatic cancer xenografts: TF10-90Y-IMP-288 alone and combined with gemcitabine. J Nucl Med. 2009 Dec;50(12):2008–16. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.067686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattes MJ, Sharkey RM, Karacay H, Czuczman MS, Goldenberg DM. Therapy of advanced B-lymphoma xenografts with a combination of 90Y-anti-CD22 IgG (epratuzumab) and unlabeled anti-CD20 IgG (veltuzumab) Clin Cancer Res. 2008 Oct 1;14(19):6154–60. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller WHC, Hartmann-Siantar D, Fisher MA, Descalle J, Lehmann W, Volkert MR. Evaluation of absorbed fractions in a mouse model for 90Y, 188Re, 166Ho, 149Pm, 177Lu and 64Cu radioisotopes. Cancer, Biotherapy and Radiopharmaceuticals. 2005 Aug;18(4) doi: 10.1089/cbr.2005.20.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hui TE, Fisher DR, Kuhn JA. A mouse model for calculating cross-organ β doses from yttrium-90-labeled immunoconjugates. Cancer. 1994;73(supplement):951. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940201)73:3+<951::aid-cncr2820731330>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotzerke J, Glatting G, Seitz U, Rentschler M, Neumaier B, Bunjes D. Radioimmunotherapy for the intensification of conditioning before stem cell transplantation: differences in dosimetry and biokinetics of 188Re-and 99mTc labeled Anti-NCA-95 MAbs. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:531–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]