Abstract

A disorder of infants and children with pathological startle response, features of other system involvement, falls, and stiffness with retained consciousness. It should be differentiated from conditions such as myoclonic epilepsy, psychogenic movement disorder, Isaac syndrome, Schwartz–Jampel syndrome, Gilles de la Tourette, and culture-specific startle syndromes such as jumping Frenchman of Maine. A 5-year-old child symptomatic with repeated falls spontaneously as well as by sound and activities since neonatal period. He was having hyperalert facies, intelligent, cooperative with mild dysmorphism. His investigations were noncontributory except giant somatosensory evoked potentials and skeletal abnormalities. He showed excellent response to clonazepam and no complications on withdrawing the antiepileptic drugs. Proper diagnosis is of great therapeutic relevance and is based on high degree of suspicion.

KEYWORDS: Differential diagnosis, hyperekplexia plus, startle

INTRODUCTION

The word startle' means “to undergo a sudden involuntary movement of the body, caused by surprise, alarm, acute pain, etc.” Startle reaction is a motor response to noxious stimuli which has a stereotyped sudden involuntary movement of the body which habituates. Startle responses can be part of hyperekplexia syndrome, psychogenic, or epileptic startle response. Persistent nonhabituating startle to minor stimuli with hyperalert gaze, inquisitive attention to environment with or without stiffness needs to be viewed with suspicion of hyperekplexia. It is an interesting movement disorder often mistaken as myoclonic epilepsy, psychogenic movement disorder, Isaac syndrome, Schwartz–Jampel syndrome, Gilles de la Tourette, and culture-specific startle syndromes such as jumping Frenchman of maine. Hyperekplexia was first described by Kirstein and Silfverskiold in 1958.[1] This is congenital disorder with major and minor forms.[2] Major if there are neonatal hypertonia and generalized stiffness, jitteriness, and rhythmic spasms with exaggerated startle response and falls and minor if stiffness is absent. Those with features of involvement of other systems are called as plus syndromes. It occurs as both sporadic and familial forms.[3] Persistent primitive reflexes, apneic spells, breath holding attacks, and exaggerated reflexes with normal cognitive and behavioral features is an important clue. Mothers might report excessive shudders and startles in the last trimester of gestation. Although considered benign, fatal complications occur with apneic spells, cardiac arrhythmias, aspiration causing cardiorespiratory arrest, laryngospasm, sudden death due to complications during anesthesia, and use of beta antagonist as well as side effects related to unnecessary treatment related to wrong diagnosis.[4] Hyperekplexia plus syndrome is characterized by lymphedema, distichiasis (double eyelashes), atopic dermatitis, cutaneous nevus, kyphoscoliosis, abnormal acetabular, phalanges, brachydactyly, clinodactyly, hypospadias, and also cardiac involvement.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis is clinical.[5] Falling and stiffness provide clues with normal electroencephalogram (EEG) with or without abnormal blink response, electromyography (EMG) discharges at rest, and genetic factors aid in diagnosis. Tonic neonatal cyanosis relieved by Vigevano maneuver characterized by forced flexion of head and neck toward trunk which is lifesaving during prolonged spasms. Head retraction response consisting of brisk involuntary backward jerk after the root of the nose or upper lip is tapped. In one study among 39 patients studied, 20% had feeding difficulty, 15% had apnea, and 10% had sleep disorders.[6]

Pathogenesis and treatment

Auditory startle reflex originates in the bulbo-pontine reticular formation from nucleus reticularis pontis caudalis. Glycine receptors are concentrated in the brainstem and spinal cord in humans. Second, symptomatic hyperekplexia usually occurs in patients with brainstem damage. The latencies of EMG responses point toward a brainstem origin. The EMG latency of the sternocleidomastoid muscle to taps on the head or face is very short, <20 ms. As the minimum delay in a cortical loop is 22.8 ms, shorter latencies need a shorter loop. Eye movement recordings also suggest a brainstem origin with reduced peak velocity of horizontal saccadic eye movements. Disynaptic reciprocal inhibition was absent in patients with a proven GLRA1 mutation which explains spasticity.

Mutation in neurotransmitter gene alpha-1 subunit of glycine receptor linked to chromosome 5q 33–35 is found in inherited patients. Other gene loci identified are SLE6A5 encoding presynaptic sodium and chloride-dependent glycine transporter, GLRB encoding beta subunit of glycine receptor, GPHN encoding glycinergic clustering molecule – gephysin, and ARHGEF9 encoding collybistin causing epilepsy in addition.[7] Other postulates are excessive neuronal excitation due to interruption of thalamic pathways which inhibit descending pathways.[5,8] Delayed maturation of control over brain stem, reticular neuronal hyperactivity as well as neurochemical imbalance between gamma aminobutric acid and excitatory transmitters and missense mutation at FOXC2 gene causing spontaneous receptor channel opening in the absence of an agonist.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Myoclonic epilepsy

Progressive myoclonic epilepsies of children have varying degrees of cognitive decline, cerebellar ataxia, epilepsy, with or without cherry red spots, and abnormal EEG.[9]

Psychogenic startle

Not seen in children below 10 years. It occurs as part of anxiety, malingering, or fictitious movement disorder sudden in onset and quickly reaches peak severity and stops abruptly. Investigations are usually normal.[10]

Isaac syndrome

It characterized by continuous muscle fiber activity due to hyperexcitability at terminal axon causing twitching, cramping, and myokymia which persists in sleep and anesthesia. Even respiratory muscle can be involved.[11]

Schwartz–Jampel syndrome

Patients become symptomatic between 3 and 10 years. The diagnostic findings are typical facial appearance, muscle hypertrophy, pitched voice, and continuous muscle fiber activity. They have slow movements with arms semi-flexed, toe walking in addition to difficulty in opening the mouth. They show myotonia clinically and electrophysiologically.[12]

Gilles de la Tourette syndrome

A syndrome which usually starts before 16 years of age with obsessions–compulsions, involuntary utterances, coprolalia, aggression, and repetitive motor activity which can be voluntarily restrained for some time.[13]

Jumping Frenchman of Maine

First reported by George Miller in 1878. Persons who are generally shy show uncontrollable jumping, yelling, hitting, and aggression of unknown cause. The possibility of genetic disease versus culture-bound tendency is considered.[14]

CASE REPORT

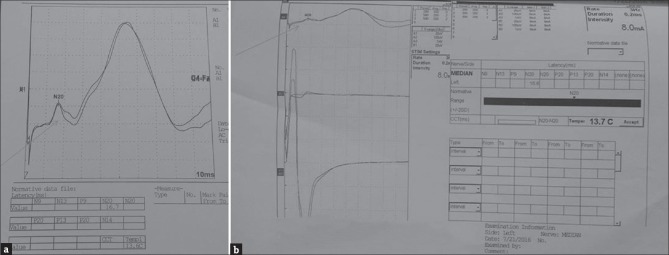

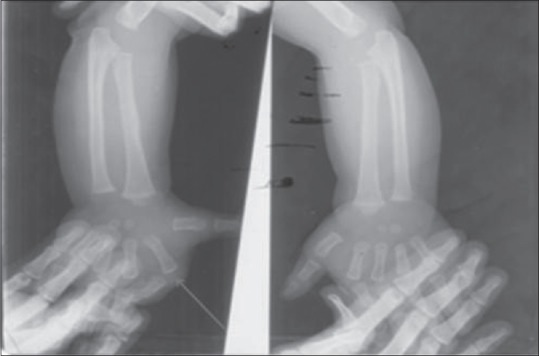

We report a 5-year-old male child from Odisha. He was born to nonconsanguineous parents by lower segment cesarean section. Indication reported as dystocia of shoulder. Neonatal period was uneventful but for the need for aspiration of a cystic swelling noticed in the neck. Antenatal experiences not clear, but had first-trimester abortion during previous pregnancy. Child was jittery, always with hyperalert facies, gained milestones normally. When he started walking at 1½ year of age, he was found to excessive jerking of all four limbs to sound, holding objects, resulting in repeated falls and dropping objects which occurred 8–10 times every day. He was investigated regionally and treated with multiple anticonvulsants with no benefit. At the time of examination, child was bright and cooperative. He had minor dysmorphic features in the form of high arched palate, prominent ears, flat bridge of nose, small eyes, malformation of both hands in the form of undue separation of middle thumb and index finger with deformity, and scoliosis. He manifested with repeated falls with retained consciousness. The movements were sudden spontaneous or precipitated by sound or actions with tilting of trunk and flexion of limbs [Video 1]. Possibility of hyperekplexia plus syndrome was considered and investigated. X-ray of the hand showed increased space between metacarpal bones and deformity of phalanges [Figure 1]. His magnetic resonance imaging and EEG done from Odisha were normal. We investigated him with neurometabolic workup, autoantibody profile for NMDA, VGKC, GAD, CK, and long loop reflexes which were noncontributory. Somatosensory evoked responses showed giant somatosensory evoked potentials and normal c reflex [Figure 2a and b]. Genetic tests were not done due to the financial constraints. The antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) were withdrawn and child treated with 0.2 mg per kg of clonazepam and child showed complete arrest of falls over a week time [Video 2].

Figure 1.

X-ray hand showing increased space between the metacarpal bones and deformity of the phalanges (regret: technician hand artifact)

Figure 2.

(a) somatosensory evoked response of median nerve showing somatosensory evoked potentials of latency 16.7 ms (b) showing normal C reflex

DISCUSSION

Our patient suffered from pathological startle syndrome from very early infancy with skeletal changes and mild dysmorphism. He did not show any response to polypharmacy with multiple AEDs tried over 3 years but showed excellent remission with clonazepam and all other drugs could be withdrawn. Although relatively benign, fatal complications are known and need a high degree of suspicion which will save the child from unwanted medications.

CONCLUSION

Recognition of this syndrome is of great significance in avoiding unnecessary interventions. Simple methods such as Vigevano maneuver is lifesaving during periods of prolonged spasm and clonazepam 0.5–0.2 mg/kg controls falls in most cases. However, the hyperekplexia plus syndrome is extremely rare and mostly sporadic and occasionally genetic studies need to be done attention to other system-related complications.

Videos Available on: www.pediatricneurosciences.com

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kirstein L, Silfverskiold BP. A family with emotionally precipitated drop seizures. Acta Psychiatr Neurol Scand. 1958;33:471–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1958.tb03533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suhren O, Bruyn GW, Tuynman JA. Hyperexplexia: A hereditary startle syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 1966;3:577–605. [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Groen JH, Kamphuisen HA. Periodic nocturnal myoclonus in a patient with hyperexplexia (startle disease) J Neurol Sci. 1978;38:207–13. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(78)90067-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vigevano F, Di Capua M, Dalla Bernardina B. Startle disease: An avoidable cause of sudden infant death. Lancet. 1989;1:216. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91226-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Praveen V, Patole SK, Whitehall JS. Hyperekplexia in neonates. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:570–2. doi: 10.1136/pmj.77.911.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shahar E, Raviv R. Sporadic major hyperekplexia in neonates and infants: Clinical manifestations and outcome. Pediatr Neurol. 2004;31:30–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tijssen MA, Vergouwe MN, van Dijk JG, Rees M, Frants RR, Brown P. Major and minor form of hereditary hyperekplexia. Mov Disord. 2002;17:826–30. doi: 10.1002/mds.10168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chokroverty S, Walczak T, Hening W. Human startle reflex: Technique and criteria for abnormal response. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1992;85:236–42. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(92)90111-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandra SR, Issac TG, Gayathri N, Gupta N, Abbas MM. A typical case of myoclonic epilepsy with ragged red fibers (MERRF) and the lessons learned. J Postgrad Med. 2015;61:200–2. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.150905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pal PK, Netravathi M. Role of electrophysiology in the evaluation of movement disorders. Prog Clin Neurosci. 2008;22:16. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newsom-Davis J, Mills KR. Immunological associations of acquired neuromyotonia (Isaacs' syndrome). Report of five cases and literature review. Brain. 1993;116:453–69. doi: 10.1093/brain/116.2.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chandra SR, Issac TG, Gayathri N, Shivaram S. Schwartz-Jampel syndrome. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2015;10:169–71. doi: 10.4103/1817-1745.159202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shapiro AK, Shapiro ES, Young JG, Feinberg TE. Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Raven Press, Publishers; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 14.John LD. Hyperkinetic disorders of movement: Historical developments to the middle of the 20-th century. J Neurol. 2015;20:55–68. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.