Abstract

Encephalocele is a rare lesion, being an embryological mesodermal anomaly which results in a defect in the cranium and dura, associated with herniation of meninges, cerebrospinal fluid, or brain tissues through a defect usually covered by scalp. Surgical management of children with giant occipital encephalocele requires careful attention to pediatric anesthetic and surgical principles. We present a case of a giant occipital encephalocele highlighting the problems encountered in its management.

KEYWORDS: Encephalocele, giant encephalocele, herniation, neonate, occipital encephalocele, surgery

INTRODUCTION

A meningoencephalocele is herniation of neural element along with meninges through a congenital defect in cranium. The incidence of encephalocele is approximately 1/5000 live births; occipital encephalocele is more common in females than males.[1,2] It is called as giant meningoencephalocele when the head is smaller than the meningoencephalocele. These giant meningoencephaloceles harbor a large amount of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and brain tissue, so there occur various surgical challenges and anesthetic challenges in positioning and intubation.[3]

CASE REPORT

A 2-month-old female child presented to the neurosurgery outpatient department with complaints of large swelling over the back of head and difficulty in feeding. The swelling was small at the time of birth, but it gradually increased in size. The child was born by normal vaginal delivery at home, had 4 siblings who were all normal. Folic acid supplementation was not taken by mother in any pregnancy. The weight of the child was 6.5 kg. On examination, patient large spherical swelling was present over occipital region and there was no head control [Figure 1]. The patient was active, conscious with no focal neurological deficit. Systemic examination was unremarkable. The head circumference was 30 cm and circumference of occipital swelling was 63 cm. The overlying skin was tense and without any CSF leak. Swelling was cystic and its size increased on crying. Fluctuation could be elicited and transillumination test was also positive. There was no any bruit or murmur over the swelling. Anterior fontanelle and posterior fontanelle were both open.

Figure 1.

Photograph of 2-year-old neonate showing a giant occipital encephalocele

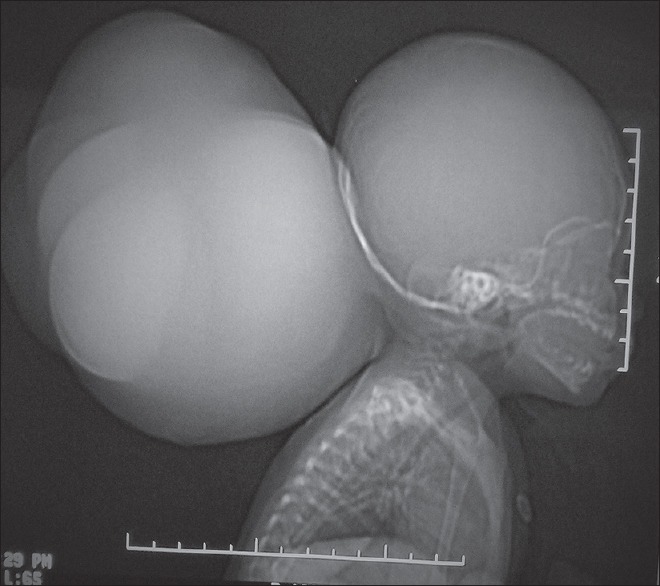

A computed tomography (CT) scan was done [Figures 2 and 3], which showed a bony defect of size 22 mm × 15 mm in occipital bone in the midline. There was herniation of CSF-filled sac through the defect into the extracalvarial soft tissue layer and herniation of bilateral cerebellar hemisphere into CSF filled sac. Features favored the diagnosis of giant occipital meningoencephalocele.

Figure 2.

Computed tomography scan showing calvarial defect of 22 mm × 15 mm in occipital bone

Figure 3.

Computed tomography scan showing cerebrospinal fluid filled sac herniating through the calvarial defect along with part of cerebellum sac

The patient routine laboratory investigation was normal. After arrangement of adequate blood, the patient was posted for surgery. The patient was operated in lateral position. A circumferential incision was given on the swelling with meticulous dissection, and hemostasis sac was opened and gradual decompression of sac done, clear fluid (CSF) came out from the sac. The protruded portion of cerebellum was excised and the dura closure was done. Scalp closure was done in layers. The patient was extubated without any difficulty and shifted to postoperative room. Preoperative weight of the patient was 6.5 kg and the postoperative weight of 3 kg. On the 3rd postoperative day, the patient developed bulging of wound. CT scan showed a mild communicating hydrocephalus which was managed by repeated lumber puncture and CSF drainage. Stitches were removed and the patient was discharged on the 10th day.

DISCUSSION

In cases of occipital meningoencephalocele, herniation of meninges, occipital lobes, and/or ventricles are common. Other contents of meningoencephalocele may be cerebellum, brainstem, or rarely, torcula. Torcula as one of the contents of encephalocele poses a greater challenge as its injury may lead to cerebral deep venous system thrombosis and its associated consequences of assault to the already compromised brain.[4]

Preoperatively, preparation for significant blood loss should be made because of potential bleeding from the suboccipital bone and the dural sinus. The ultimate prognosis, however, depends on various factors.[5] Proper positioning of the patient is required for successful endotracheal intubation. Although, usually, patients with an occipital meningoencephalocele are operated in prone position, a giant size prevent this positioning and the patient has to be kept in lateral position as seen in the present case. Endotracheal intubation may be difficult due to large swelling and short neck, so alternative airway management options should be kept ready before starting anesthetic induction. Laryngeal mask airway of appropriate size, with high-frequency jet ventilation, fiberoptic bronchoscope, a cricothyroid cannula, and preparations for tracheostomy should be made. Due to a low functional reserve volume, pediatric patients are more prone to develop hypoxia, hypotension, and bradycardia and even cardiac arrest. Therefore, very close monitoring is required.[6] Elective surgery provides the time to patients to gain weight and strength and offers the surgeon for selection of the best technique. However, large meningoencephaloceles mostly require urgent surgical treatment to avoid damage to sac. Surgery of large meningoencephaloceles where functional brain matter is a content of the sac can sometime be extremely difficult. Ischemic or necrotic neural tissue can be excised. In addition, intracranial vessels may enter into sac and loop out of the sac to supply normal brain parenchyma, and excision of brain in such cases can produce infarctions.[7] Aspiration of the CSF before skin incision in large meningoencephalocele helps in dissection of the sac. For a circular meningoencephalocele with a small occipital bone defect, a transverse incision is sufficient. A vertical incision is required in patients with meningoencephalocele extending above and below the transverse sinus. Care should be taken to identify the contents of the sac. Rarely, the sagittal sinus torcula and the transverse sinus are seen in the vicinity of the sac.[8] It is desirable to preserve the neural tissue. The dura has to be repaired meticulously to get a water-tight closure to prevent CSF leak. The dural defect can be repaired using the periosteum graft. In neonates and infants, no attempt should be made to cover the bone defect by a bone graft.[9] Many factors affect the outcome of patients with occipital meningoencephaloceles which include site, size, amount of brain herniated into the sac, presence of brainstem or occipital lobe with or without the dural sinuses in the sac, and presence of hydrocephalus. The presence of gross brain tissue in sac, associated hydrocephalus, or congenital anomalies are unfavorable prognostic factors. It is observed that microcephalic neonates with sac containing cerebrum, cerebellum, and brain stem structures have poor prognosis, even if a craniotomy is performed around the coronal suture for secondary craniostenosis.[10]

CONCLUSION

The management of occipital encephaloceles can be complicated and should be individualized. In a tense, giant occipital meningoencephalocele problems encountered are essentially because of the large size and induced neonate handling, positioning in operation theater, intubation, and blood loss during resection of the large amount of redundant skin.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singh AK, Sharma MS, Agrawal VK, Behari S. Surgical repair of a giant naso-ethemoidal encephalocele. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2006;1:293–4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mealey J, Jr, Dzenitis AJ, Hockey AA. The prognosis of encephaloceles. J Neurosurg. 1970;32:209–18. doi: 10.3171/jns.1970.32.2.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahapatra AK. Management of encephalocele. In: Ramamurthi R, editor. Text Book of Operative Neurosurgery. Vol. 1. New Delhi: BI Publications Pvt. Ltd.; 2005. pp. 279–90. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verma SK, Satyarthee GD, Singh PK, Sharma BS. Torcular occipital encephalocele in infant: Report of two cases and review of literature. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2013;8:207–9. doi: 10.4103/1817-1745.123666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goel V, Dogra N, Khandelwal M, Chaudhri R. Management of neonatal giant occipital encephalocele: Anaesthetic challenge. Indian J Anaesth. 2010;54:477–8. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.71022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fraser J, Petros A. High-frequency oscillation via a laryngeal mask airway. Anaesthesia. 1999;54:404. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raja RA, Qureshi AA, Memon AR, Ali H, Dev V. Pattern of encephaloceles: a case series. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2008;20:125–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nath HD, Mahapatra AK, Borkar SA. A giant occipital encephalocele with spontaneous hemorrhage into the sac: A rare case report. Asian J Neurosurg. 2014;9:158–60. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.142736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahapatra AK. Frontoethmoidal encephalocele. A study of 42 patients. In: Samii M, editor. Skull Base Anatomy, Radiology and Management. Basel, Switzerland: S Karger Basel; 1994. pp. 220–3. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caviness VS, Jr, Evarard P. Occipital encephalocele: a pathologic and anatomic analysis. Acta Neuropathol. 1975;32:245–55. doi: 10.1007/BF00696573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]