Highlights

-

•

OMMT/paraffin composite PCM were prepared.

-

•

OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT composite phase change material.

-

•

Paraffin is intercalated into the interlayer of OMMT.

-

•

OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT has stable thermal properties.

-

•

OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT has a better heat storage prosperity.

Keywords: Phase change material, Thermal property, Paraffin, Carbon nanotube

Abstract

A composite phase change material (PCM) comprised of organic montmorillonite (OMMT)/paraffin/grafted multi-walled nanotube (MWNT) is synthesized via ultrasonic dispersion and liquid intercalation. The microstructure of the composite PCM has been characterized to determine the phase distribution, and thermal properties (latent heat and thermal conductivity) have been measured by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and a thermal constant analyzer. The results show that paraffin molecules are intercalated in the montmorillonite layers and the grafted MWNTs are dispersed in the montmorillonite layers. The latent heat is 47.1 J/g, and the thermal conductivity of the OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT composites is 34% higher than that of the OMMT/paraffin composites and 65% higher than that of paraffin.

1. Introduction

Phase change material (PCM) can absorb and/or releasing a significant amount of latent heat due to a phase transition when the phase transition temperature is within a specified temperature range. PCM has achieved wide application in the field of energy storage and thermal insulation, such as building energy (Zhang et al., 2004, Li et al., 2013, Li et al., 2010), air-conditioning (Harold et al., 1975), solar thermal storage (Cabeza et al., 2007, Schossig et al., 2005, Wu and Fang, 2011, Nithyanandam and Pitchumani, 2014), temperature regulating textiles (Nihal and Emel, 2007, Sánchez et al., 2010) and electronic thermal control (Simone et al., 2008, Huang et al., 2011). Different phase change materials have different phase change temperatures and phase transition enthalpies. Paraffin is perhaps the most common phase change material because of a characteristic of high storage density, minimal tendency to supercool,low vapor pressure of the liquid phase, chemical stability, non-toxicity, and relatively low cost (Wang et al., 2009, Kuznik et al., 2011, Nihal et al., 2011).

Various technologies, including microencapsulation (Su et al., 2007, Cho et al., 2002, Onder et al., 2008, Qiu et al., 2013), adsorption (Zhang et al., 2004), adsorption (Zhang et al., 2004) and intercalation (Fang et al., 2010, Li et al., 2012) are used to synthesize composite PCMs. Composite PCMs synthesized by different techniques have distinct characteristics in thermal, mechanical, and physical properties. Currently, composite PCMs with high thermal performance and durability have become the subject of study (Li et al., 2011, Karaipekli and Sari, 2010, Zhang et al., 2014, Cai et al., 2015).

Montmorillonite (MMT) is a natural layered material and the main ingredient is silicate. The chemical formula of MMT is A12O3·4SiO2·3H2O, and MMT is 2:1 type layered silicate – i.e., each unit cell of MMT contains two layers of silicon oxygen tetrahedra and one layer of aluminum (magnesium) oxygen octahedra. The tetrahedra and octahedra are connected through the shared oxygen atoms. The thickness of each layer is 1 nm and the closely packed arrangement forms a highly ordered crystal structure. MMT exhibits poor compatibility with organic molecules because the surface of MMT and the interspace between the layers are hydrophilic. Thus, MMT requires organic modification to form composites with organic components.

The ultrasonic dispersion method has higher intercalating efficiency than other traditional intercalating composite methods, such as the solvent evaporation method and the mechanical intercalated method. It is easy-controlled and environment friendly. The energy consumption can be reduced remarkably (Sato et al., 2008).

In order to improve the shape-stability and thermal properties of PCM, we synthesized OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT composite PCM by ultrasonic dispersion and liquid intercalation. Cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide was used in organic modification of montmorillonite. The novelty in the paper is the preparation method of the composite PCM and the formation of the intercalation micro-structure with MMT and MWNT, which lead to the improvement of the thermal properties of PCM.

XRD and SEM were used to characterize the composition and structure of composite PCM. DSC and thermal constant analyzer were used to characterize the thermal properties of the composite PCM.

2. Materials and experimental method

2.1. Materials

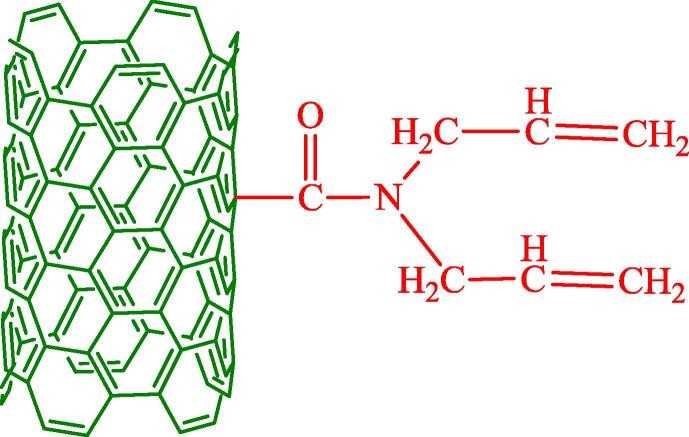

Na-montmorillonite (Na-MMT, Zhejiang Fenghong New Material Co.) with purity >88% and CEC: 85 meq/100 g was selected for the experiments. The organic montmorillonite (OMMT) was home-made with Cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (Kao et al., 2012). Paraffin with a phase transition temperature of 26 °C (Shijiazhuang Caldecott Phase Change Materials Co., Ltd) and cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CATB, Chengdu Kelong Chemical Reagent Factory, AR) were acquired from commercial sources. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWNT, Shenzhen) were acquired and grafted carbon nanotubes (grafted MWNT) were prepared. A schematic diagram of the grafted MWNT is showed in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The schematic diagram of the grafted MWNT.

2.2. Synthesis of OMMT/paraffin composite PCM

Composite PCMs with OMMT/paraffin and OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT were prepared by the procedures described below.

2.2.1. Synthesis of OMMT/paraffin composite PCM

-

(1)

10 g OMMT was added to ethanol in a three-necked flask, and the solution was stirred at 1500 rpm and 40 °C until uniform to obtain a suspension of OMMT.

-

(2)

6 g PCM were dissolved in ethanol, and the solution was added to the suspension of OMMT. The mixture was stirred for 10 min.

-

(3)

The mixture was stirred at 75 °C. Ethanol was recycled by condensation in vacuum until completely evaporated.

-

(4)

The product was dried in vacuum at 60 °C for 24 h. The product was ground to obtain the OMMT/paraffin composite PCM.

2.2.2. Synthesis of OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT composite PCM

-

(1)

10 g OMMT was added to ethanol in a three-necked flask. The solution was stirred at 1500 rpm and 60 °C until uniform to produce a suspension of OMMT.

-

(2)

6 g PCM and 0.16 g grafted MWNT were dissolved in ethanol. The solution was added to the suspension of OMMT and stirred for 10 min. The mixture was placed in an ultrasonic water bath at 60 °C for 30 min. After that, the mixture was placed in a water bath at 75 °C and stirred. Ethanol was recycled by condensation in vacuum until evaporated.

-

(3)

The product was dried in vacuum at 60 °C for 24 h, then ground to obtain the OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT composite PCM.

2.3. Characterization and testing

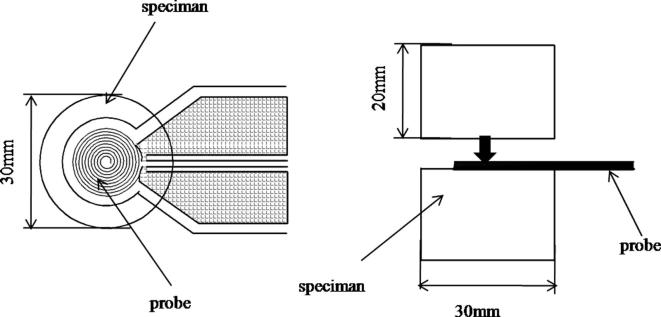

The surface morphology of PCM composites was examined by SEM imaging at 20 kV (Sirion 200, FEI Company, Netherlands). Structural analysis was performed by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Smart Lab 3, RIGAKU, Japan) using a Cu target. Interlayer spacings of the clays were measured before and after intercalation and modification. The enthalpy of the composite phase change was measured by calorimetry (DSC, DSC 200 F3 Maia, NETZSCH, Germany). The enthalpy of composite PCM was characterized by DSC (200 F3 Maia, NETZSCH Co., Germany). The scanning temperature range is from −20 °C to 60 °C. The scanning rate was 5 degree per minute. Finally, thermal conductivity, thermal diffusivity and heat capacity of composite samples were measured using a Hot Disk Thermal Constant Analyser (TPS2500, Hot Disk AB Company, Sweden). The methodology of measurement adopted with the hot disk is the Transient Plane Source Method. The specimen was a cylinder with height of 20 mm and diameter of 30 mm. Two same specimens were piled tightly and a probe with a radius of 3.189 mm was inserted between them. The schematic diagram of the thermal conductivity test is shown in Fig. 2. The heat storage and release properties of composite PCMs were examined by multi-channel temperature recorder (TOPRIE-TP700, Bost, Shenzhen).

Fig. 2.

The schematic diagram of the thermal conductivity test.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. XRD analysis

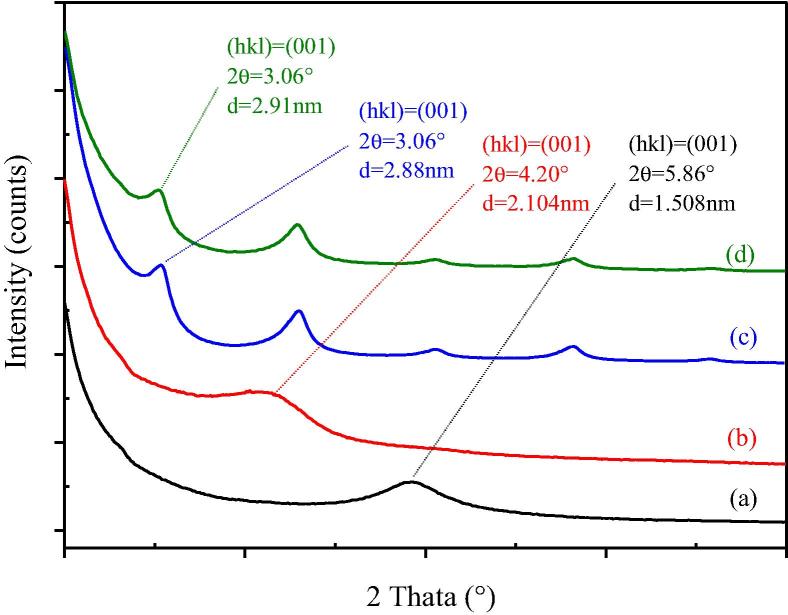

The X-ray diffraction patterns of Na-MMT, OMMT, OMMT/paraffin and OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT PCMs are shown in Fig. 3. The characteristic peak of the (0 0 1) crystal plane of Na-MMT appears at 2θ = 5.86°. The layer spacing is calculated according to the Bragg equation (Eq. (1))

| (1) |

where d is the layer spacing, θ is the glancing angle, λ is the X-ray wavelengths, and n is the diffraction series. When λ is 0.15418 nm and n is 1, d = 1.508 nm.

Fig. 3.

XRD analysis of MMT: (a) Na-MMT; (b) OMMT; (c) OMMT/PCM; (d) OMMT/PCM/grafted.

After organic modification with CTAB, the characteristic peak of the (0 0 1) crystal plane of MMT shifted to 2θ = 4.20° corresponding to d = 2.104 nm. No new diffraction peaks appeared (Fig.3(b)), indicating that inserting CTAB molecules into MMT layers increased the layer spacing of montmorillonite. The organic modification alters the polarity of interface and the microenvironment of the interlayers. Consequently, the polarity of the interlayers is reduced and the lipophilicity of the interlayers is increased, providing a favorable condition for organic PCM molecules to insert into the MMT interlayers. Fig.3(c) shows that the (0 0 1) peak shifts to 2θ = 3.06°, corresponding to d = 2.88 nm for OMMT/paraffin, when PCM inserts into the interlayers of OMMNT.

Fig. 3 also shows that the interlayer spacing of OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT composite PCM is 2.91 nm, which is slightly greater than that of OMMT/paraffin, indicating that the grafted MWNT does not insert into the interlayer completely.

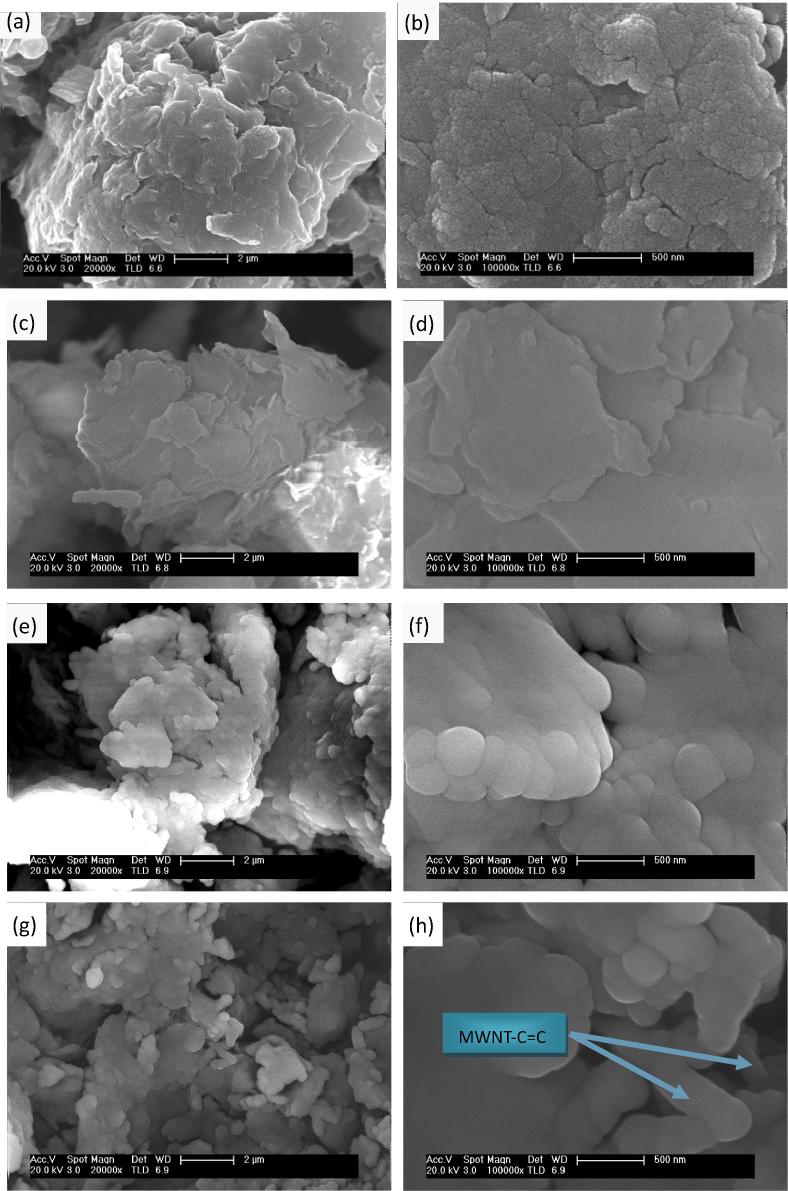

3.2. SEM analysis

Fig. 4 shows micrographs of MMT, OMMT, OMMT/paraffin and OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT. As shown in Fig. 4, the layers of montmorillonite pack tightly and it is difficult for organic PCM to insert into the interlayers (Fig. 4(a) and (b)). After organic modification with CATB, the layers of MMT increase separation, facilitating intercalation of PCM (Fig. 4(c) and (d)).

Fig. 4.

SEM analysis of: (a and b) MMT; (c and d) OMMT; (e and f) OMMT/paraffin; (g and h) OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT.

Fig. 4(e) and (f) shows thick layers of MMT, a result of the insertion of paraffin into the OMMT layers. In addition, some paraffin was absorbed at the edges of the laminate of MMT due to the action of capillary forces.

Fig. 4(g) and (h) shows that carbon nanotubes disperse uniformly in OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT, a result of carbon chains introduced to the surface of MWNT after MWNT is grafted. Consequently, the surface structure of the grafted MWNT resembles the chain structure of paraffin, imparting compatibility with paraffin in accord with the similar dissolve mutually theory.

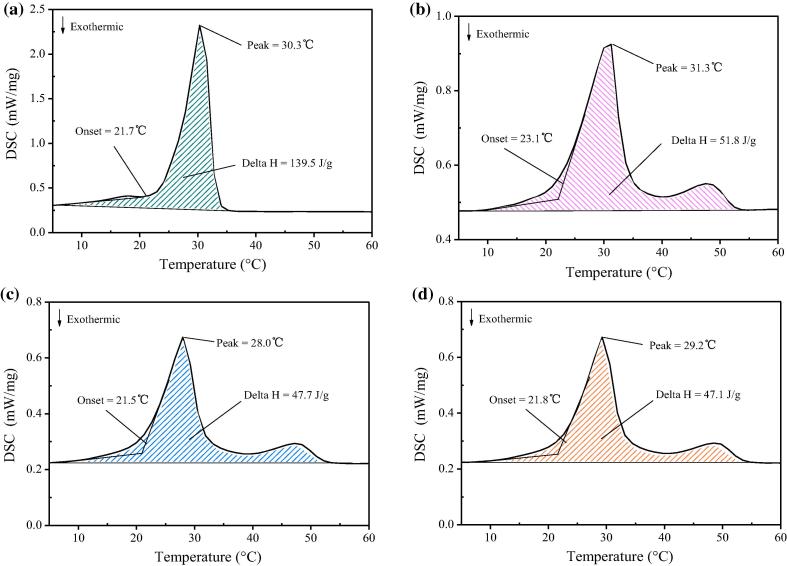

3.3. DSC analysis

Fig. 5 shows DSC curves of paraffin, OMMT/paraffin and OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT, and Table 1 presents the corresponding thermal properties. Fig. 5(a) shows that the phase change temperature of paraffin occurs at 21.7 °C and the temperature of the endothermic peak is 30.3 °C. The phase change temperature and endothermic peak temperature of OMMT/paraffin is 23.1°Cand 31.3 °C, respectively. The values are 1–2 °C higher than those of paraffin, ostensibly because the layers of OMMT restrain the movement of the paraffin molecules inserted into the OMMT layers.

Fig. 5.

DSC analysis of: (a) PCM; (b) OMMT/PCM; (c) OMMT/PCM/MWNT; (d) OMMT/PCM/MWNT after 100 times of cycles.

Table 1.

Thermal property of PCMs.

| Sample | Phase change temperature (°C) | Endothermic peak temperature (°C) | The theoretical latent heat (J/g) | The measured latent heat (J/g) | The relative errors (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paraffin | 21.7 | 30.3 | 139.5 | ||

| OMMT/paraffin | 23.1 | 31.3 | 52.3 | 51.8 | 0.96 |

| OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT | 21.5 | 28 | 47.56 | 47.7 | 0.29 |

The latent heat of PCM is calculated by Eq. (2) (Kao et al., 2012):

| (2) |

where ΔHCPCM is the latent heat of the composite PCM, ΔHPCM is the latent heat of paraffin, andηis the mass fraction of paraffin in the composite PCM.

Table 1 shows that the latent heat of the OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT is 47.7 J/g. The value is higher than many other composite PCMs, which is shown in Table 2. The difference between the theoretical latent heat and the measured value for OMMT/paraffin is 0.96%, while the difference between the theoretical and measured values for OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT is 0.29%. The results demonstrate that the binding force for OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT to paraffin is greater than that of OMMT/paraffin.

Table 2.

Latent heat and thermal conductivity of the composite PCMs.

| Composite PCM | Latent heat (J/g) | Thermal conductivity (W/m K) |

|---|---|---|

| CA–LA/gypsum (Simone et al., 2008) | 35.2 | – |

| CA–PA/gypsum (Su et al., 2007) | 42.5 | – |

| Capric–myristic acid (20 wt%)/VMT (Wang et al., 2009) | 27 | 0.065 |

| Capric–myristic acid/VMT/2 wt% EG (Wang et al., 2009) | 26.9 | 0.22 |

| Emerest2326/gypsum (Wu and Fang, 2011) | 35 | – |

| BS/MMT composite PCM (Zhang et al., 2004) | 41.81 | – |

| DA–GGBS composite-Endo (Zhang et al., 2014) | 22.51 | – |

| DA–GGBS composite-Exo (Zhang et al., 2014) | 21.62 | – |

Fig. 5(c) shows that the phase change temperature and endothermic peak temperature of the OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT PCM are lower than those of paraffin. This is the result of two combined actions. On the one hand, the mobility of paraffin molecular chains is restricted by the OMMT layers, and the phase change temperature has increased. On the other hand, the thermal conductivity of the PCM is greater than that of paraffin. Therefore, the heat transfer of the OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT PCM during phase change process is faster than that of paraffin.

Fig. 5(d) is the DSC curve of OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT PCM after 100 thermal cycles between 60 °C and 10 °C. The latent heat of the composite PCM is 47.1 J/g after 100 thermal cycles, 1.26% less than before cycling, indicating thermal stability. The slight decrease in latent heat after thermal cycling is attributed to slight degradation of the bonding between paraffin and the MMT layers resulting from cyclic thermal stress.

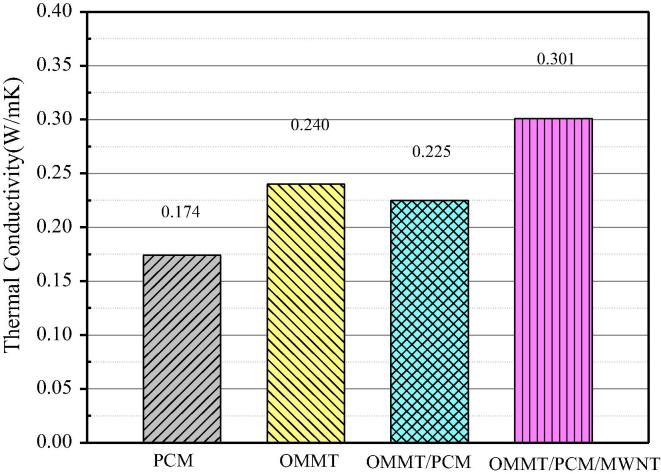

3.4. Thermal conductivity

Fig. 6 shows the thermal conductivity of the PCMs. The thermal conductivity of Paraffin, OMMT/paraffin, and OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT PCM was measured at 20 °C for three times. The average value of the three data is taken as the final value of the thermal conductivity. The precision of the Hot Disk is ±3%. The thermal conductivity of the OMMT/paraffin binary composites is 0.225 W/m·K, an increase of 29% compared to paraffin. The increase is attributed to the greater thermal conductivity of OMMT relative to paraffin.

Fig. 6.

Thermal conductivity of OMMT/PCM and OMMT/PCM/MWNT.

The thermal conductivity of the OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT PCM is 0.301 W/m·K, 34% greater than that of OMMT//Paraffin. The increase stems mainly from the conductivity of MWNT. The thermal conductivity of the grafted MWNT is about 3000 W/m·K (Kim et al., 2001). Moreover, the grafted MWNT is uniformly dispersed in the OMMT and paraffin (Fig. 4(g–h)), boosting the conductivity of the composite PCM. The thermal conductivity of the OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT is higher than other composite PCMs, which is shown in Table 2.

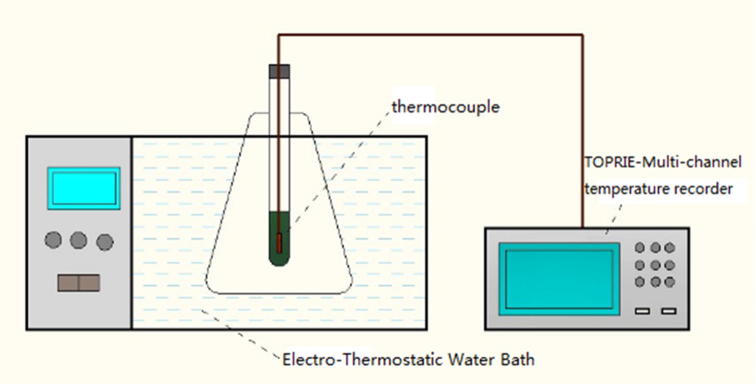

3.5. Heat storage and heat release properties

The schematic diagram of experimental installation is shown in Fig. 7. 20 g of OMMT/PCM/MWNT in a test tube was put in the water basin. Firstly, the water basin was heated from 5 °C to 50 °C. Then, the water basin was cooled from 50 °C to 5 °C. The temperature was recorded by a multi-channel temperature recorder and the heat storage and heat release curves were obtained.

Fig. 7.

Schematic diagram of storage/release heat properties test.

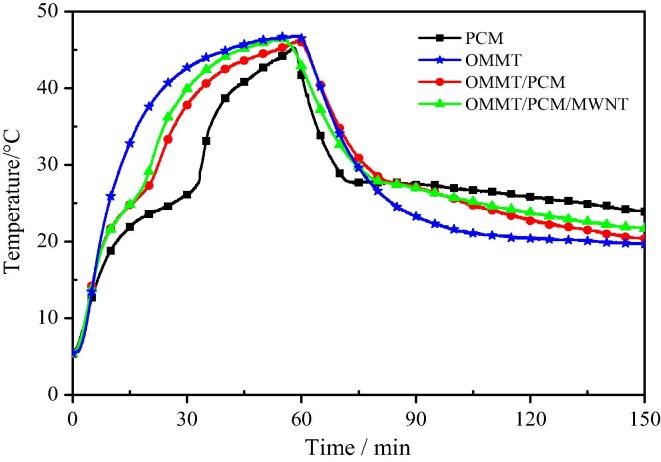

Fig. 8 shows the heat storage and heat release curves of the OMMT/PCM and OMMT/PCM/MWNT. For both OMMT/paraffin and OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT PCMs, an endothermic plateau appears at 20–28 °C and an exothermic platform appears at 25–28 °C, indicating that the materials exhibit the capacity to store and release heat.

Fig. 8.

The heat storage and heat release curves of OMMT/PCM and OMMT/PCM/MWNT.

Increasing the temperature from 20 to 30 °C requires 12 min and 14.3 min for OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT and OMMT/paraffin, respectively, indicating a greater heat storage rate for OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT relative to OMMT/paraffin. Moreover, Fig. 8 shows that OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT exhibits a greater rate of heat release than OMMT/paraffin when the temperature drops from 30 to 20 °C. This behavior stems from two reasons: OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT has a lower heat latent than OMMT/paraffin, and the thermal conductivity of OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT is greater than that of OMMT/paraffin.

4. Conclusions

A ternary OMMT/PCM/MWNT composite PCM was synthesized using ultrasonic dispersion and liquid intercalation. The crystal structure, morphology and thermal properties of the OMMT/PCM/MWNT composite PCM were characterized, leading to the following conclusions:

-

(1)

The interlayer spacing of OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT is greater than that of OMMT, indicating that paraffin intercalated into the OMMT. The grafted MWNT is well dispersed in the interlayer of OMMT, and paraffin is intercalated into the interlayer of OMMT and absorbed at OMMT edges.

-

(2)

The latent heat of the OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT is 47.7 J/g, and the latent heat is reduced only slightly after 100 thermal cycles, reflecting the thermal stability of the composite PCM.

-

(3)

The thermal conductivity of the OMMT/paraffin/grafted MWNT PCM increased 34% relative to the OMMT/paraffin, and the composite PCM exhibited a greater heat storage rate than the OMMT/paraffin.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from the Gill Composites Center at USC. The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support for this research from the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2242016K41003) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51178102).

References

- Cabeza L.F., Castellón C., Nogués M. Use of microencapsulated PCM in concrete walls for energy savings. Energy Build. 2007;39:113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y., Sun G., Liu M. Fabrication and characterization of capric–lauric–palmitic acid/electrospun SiO2 nanofibers composite as form-stable phase change material for thermal energy storage/retrieval. Sol. Energy. 2015;118:87–95. [Google Scholar]

- Cho J.S., Kwon A., Cho C.G. Microencapsulated of octadecane as a phase-change material by interfacial polymerization in an emulsion system. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2002;280:260–266. [Google Scholar]

- Fang G.Y., Li H., Chen Z. Preparation and characterization of stearic acid/expanded graphite composites as thermal energy storage materials. Appl. Energy. 2010;35:4622–4626. [Google Scholar]

- Harold G. Lorsch, Kenneth W. Kauffman, Jesse C. Denton. Thermal energy storage for solar heating and off-peak air conditioning. Energy Convers. 1975;15:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Huang M.J., Eames P.C., Norton B. Natural convection in an internally finned phase change material heat sink for the thermal management of photovoltaics. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 2011;95:1598–1603. [Google Scholar]

- Kao H., Li M., Lv X. Preparation and thermal properties of expanded graphite/paraffin/organic montmorillonite composite phase change material. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2012;107:299–303. [Google Scholar]

- Karaipekli A., Sari A. Preparation, thermal properties and thermal reliability of eutectic mixtures of fatty acids/expanded vermiculite as novel formstable composites for energy storage. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2010;16:767–773. [Google Scholar]

- Kim P., Shi L., Majumdar A. Thermal transport measurements of individual multiwalled nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2001;87:215502. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.215502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznik F., David D., Johannes K. A review on phase change materials integrated in building walls. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011;15:379–391. [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Liu X., Fang G.Y. Preparation and characteristics of n-nonadecane/cement composites as thermal energy storage materials in buildings. Energy Build. 2010;42:1661–1665. [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Wu Z., Kao H. Study on preparation, structure and thermal energy storage property of capric–palmitic acid/attapulgite composite phase change materials. Appl. Energy. 2011;88:3125–3132. [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Wu Z.S., Tan J.M. Properties of form-stable paraffin/silicon dioxide/expanded graphite phase change composites prepared by sol-gel method. Appl. Energy. 2012;92:456–461. [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Wu Z.S., Tan J.M. Heat storage properties of the cement mortar incorporated with composite phase change material. Appl. Energy. 2013;103:393–399. [Google Scholar]

- Nihal Sarier, Emel Onder, Serap Ozay. Preparation of phase change material–montmorillonite composites suitable for thermal energy storage. Thermochim. Acta. 2011;524:39–64. [Google Scholar]

- Nihal Sarier, Emel Onder. The manufacture of microencapsulated phase change materials suitable for the design of thermally enhanced fabrics. Thermochim. Acta. 2007;452:149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Nithyanandam K., Pitchumani R. Optimization of an encapsulated phase change material thermal energystorage system. Sol. Energy. 2014;107:770–788. [Google Scholar]

- Onder E., Sarier N., Cimen E. Encapsulation of phase change material by complex coacervation to improve thermal performance of woven fabrics. Thermochim. Acta. 2008;467:63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Paula, Sánchez-Fernandez M. Victoria, Romero Amaya. Development of thermo-regulating textiles using paraffin wax microcapsules. Thermochim. Acta. 2010;498:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X., Song G., Chu X., Li X. Microencapsulated n-alkane with p(n-butyl methacrylate-co-methacrylic acid) shell as phase change materials for thermal energy storage. Sol. Energy. 2013;91:212–220. [Google Scholar]

- Sato K., Li J.-G., Kamiya H., Ishigaki T. Ultrasonic dispersion of TiO2 nanoparticles in aqueous suspension. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2008;97:2481–2487. [Google Scholar]

- Schossig P., Henning H.M., Gschwander S. Micro-encapsulated phase-change materials integrated into construction materials. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 2005;89:297–306. [Google Scholar]

- Simone Raoux, Robert M. Shelby, Jean Jordan-Sweet. Phase change materials and their application to random access memory technology. Microelectron. Eng. 2008;85:2330–2333. [Google Scholar]

- Su J.F., Huang Z., Ren L. High compact melamine-formaldehyde microPCMs containing n-octadecane fabricated by a two-step coacervation method. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2007;285:1581–1591. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zhang Y., Xiao W. Review on thermal performance of phase change energy storage building envelope. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2009;54:920–928. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Shuangmao, Fang Guiyin. Dynamic performances of solar heat storage system with packed bed using myristic acid as phase change material. Energy Build. 2011;43:1091–1096. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D., Li Z.J., Zhou J.M., Wu K. Development of thermal energy storage concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004;34:927. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N., Yuan Y., Yuan Y. Effect of carbon nanotubes on the thermal behavior of palmitic–stearic acid eutectic mixtures as phase change materials for energy storage. Sol. Energy. 2014;110:64–70. [Google Scholar]