Abstract

Thoracic ossification of the ligamentum flavum (TOLF)is a common cause of thoracic spinal canal stenosis and has been reported almost exclusively in East Asian countries. In this study, we established a relationship between bone morphogenic protein 2 (BMP-2) and TOLF. We divided patients into two groups according to severity of ossification and identified susceptible loci through exome sequencing. We identified 39 novel likely pathogenic variants in 29 genes in the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) superfamily or TGF-β/BMPs signaling pathway, including two missense variants in BMP-2 (NM_001200.3) exon region, c.460C>G:p.(R154G) and c.584G>T:p.(R195M). Further Sanger sequencing and genotyping suggested the variants were only found in patients with long regional OLF. Bioinformatic assays predicted the two BMP-2 variants to cause significant alterations to gene and protein expression. Functional assays showed upregulation of BMP-2 expression, increased osteogenic marker expression, and enhanced osteogenic differentiation. Collectively, these results suggest a genetic contribution to the pathogenesis of TOLF, particularly in patients with long segment disease, and that nucleotide substitutions associated with increased BMP-2 expression may be involved in TOLF pathogenesis.

Introduction

Thoracic ossification of the ligamentum flavum (TOLF) is a leading cause of thoracic spinal canal stenosis and myelopathy,1 present in 72.3% of patients with thoracic spinal canal stenosis.2 The incidence of TOLF is highest in East Asian populations, and a prevalence of 63.9% has been reported in the Chinese population.3 Regional differences suggest that genetic factors may have a role in TOLF.

Ossification of the ligamentum flavum (OLF), ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL), and diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) are now collectively known as disorders of the ossification of the spinal ligament. Over the past several decades, a variety of genetic investigations have documented many genes and loci involved in the molecular and genetic pathobiology of ossification of the spinal ligament.4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Histologically, the progression of ossification of the spinal ligament correlates with endochondral ossification.10

The transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β)/bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) signaling pathway have well-established roles in bone formation during mammalian development and exhibit versatile functions in the body.11 BMPs act on the early stage of mesenchymal/osteoprogenitor cells and induce a biological cascade of cellular events leading to endochondral ossification.12 Several recombinant forms of BMPs have been shown to induce bone formation in vivo, and we have successfully used recombinant human BMP-2 to induce OLF in rats.13

Previous studies suggest that many TGF-β/BMPs gene variants are associated with OPLL.8, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 However, to date, there is no published literature associating TGF-β/BMPs-related variants with OLF. In this study, we identified novel heterozygous variants in the genes on TGF-β/BMPs signaling pathway using whole-exome sequencing. In particular, BMP-2 gene variants recently reported are associated with OPLL in the Han Chinese population.16, 19, 20 We further use bioinformatics and functional assay to establish the association of BMP-2 as a susceptibility gene in causing TOLF in the Chinese Han population.

Materials and methods

Subjects and DNA samples

DNA samples were obtained from the Department of Orthopedics Biobank, Peking University Third Hospital, and their use was approved by the Medical Scientific Research of Peking University Third Hospital (PUTH-REC-SOP-06-3.0-A27, 2014003).

Unrelated patients with clinically established diagnosis of TOLF and control subjects who visited the orthopedic clinics between May 2013 and November 2015 who have given written informed consent were investigated. TOLF was diagnosed by clinical specialists based on clinical symptoms and radiologic features.21 The patients were classified according to the severity of ossification, based on imaging findings. In addition, we excluded patients with OPLL or other ossification disorders involving the spinal ligament. All patients were symptomatic and required medical intervention, and many patients underwent spinal surgery before or during the study. All control subjects were over 55 years old, and have a spinal disease excluding OLF and ossification disorders of the spinal ligament, had no radiographic signs of ossification of the spinal ligament. The participants exhibiting ankylosing spondylitis (AS) or DISH, or with history of exposure to pharmacologic agents that affect bone or calcium metabolism were excluded.

Anticoagulated whole-blood samples from each participant were obtained using vacuum tubes containing EDTA. Genomic DNA was extracted from the blood samples using a QIAamp DNA Blood Midi Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Whole-exome sequencing

Briefly, exome capture was performed using SureSelect Human All Exon V5(Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA),and sequencing was performed using an Illumina HiSeq 2000 (San Diego, CA, USA) with an average coverage depth of 50 ×. After removing the sequence adaptors and low-quality reads, Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA)22 was used to align the reads to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) human reference genome (GRCh37/hg19). Following duplicate removal, local realignment and base quality recalibration using Picard (http://sourceforge.net/projects/picard/) and GATK,23 SNP and Indel calling were performed using SAMtools and were annotated using ANNOVAR,24 with reference to dbSNP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP) and The 1000 Genomes Project database (http://browser.1000genomes.org/index.html).

Sanger sequencing

Two novel heterozygous variants in BMP-2 were genotyped through Sanger sequencing. We performed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in a 20-μl volume containing 2 μl extracted genomic DNA with 5 U Platinum TaqDNA Polymerase (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA, USA) and 10 × buffer supplied by the manufacturer. Next, the PCR products were treated with BigDye and HiDi reactions. The final products were analyzed in a 96-well PRISM 3730 DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Detailed primer sequences and reaction conditions are described in Supplementary Material S1.

Variation predictions and conservation analysis

Potentially significant variants identified from secondary data analysis were evaluated using online tools PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org/), PROVEAN (http://provean.jcvi.org/index.php), Align GVGD (http://agvgd.iarc.fr/), Mutation Taster (http://mutationtaster.org/), and Mutation Assessor (http://mutationassessor.org/). The conservation status of the variants were estimated by Clustal W.

Cell culture and osteogenic differentiation

The MC3T3-E1 (mouse pre-osteoblast) cell lines were provided by Peking University Third Hospital Medical Research Center. The cells were cultured in minimum essential medium (α-MEM, GIBCO, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, GIBCO). Osteogenic differentiation medium was composed of complete medium supplemented with 0.1 μm dexamethasone, 50 mg/l l-ascorbic acid, and 10 mm β-glycerophosphate.

Plasmid transfection and western blot analysis

The pCMV6-Entry vector carrying the human BMP-2 cDNA ORF and the C-terminal myc-DDK-tag (referred to as WT) was purchased from OriGene Technologies (Beijing, China). Two mutant BMP-2 plasmids, c.460C>G:p.(R154G) and c.584G>T:p.(R195M), were generated using site-directed mutagenesis. Detailed primer sequences and reaction conditions are described in Supplementary Material S2.

The MC3T3-E1 cells were transfected with WT or mutant BMP-2 plasmids in three independent experiments. The cells were seeded in growth medium overnight and then transfected with plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol. After culturing for 72 h in basic or osteogenic differentiation medium, the cells were collected, lysed, and total protein extracted. Western blot was performed as previous study25 with an anti-DDK (FLAG) rabbit-anti-mouse polyclonal antibody (TA100023, 1/2000, OriGene) or an anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (anti-GAPDH) rabbit-anti-mouse polyclonal antibody (ab9485, 1/2500, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) as primary antibodies, and a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit antibody as secondary antibody.

To determine the extent of osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells transfected with WT or mutant BMP-2 plasmids, the levels of an early osteogenic indicator, ALP; and two late indicators, OCN and OPN, were assessed by western blot analysis at defined time points. The following primary rabbit-anti-mouse antibodies were used: anti-ALP (ab95462, 1/2000, Abcam); anti-OCN (ab93876, 1/500, Abcam); anti-OPN (ab8448, 1/1000, Abcam).

Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity and Alizarin red staining

To determine the osteogenic differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells transfected with WT or mutant BMP-2 plasmids in the osteogenic differentiation medium, ALP activity at day 7 and Alizarin red staining at day 14 were performed as previous reported.26

Data submission

Novel variants identified in genes in the TGF-β superfamily or TGF-β/BMPs signaling pathway has been submitted to Leiden Open Variation Database 3.0 (LOVD3) at: http://databases.lovd.nl/shared/individuals (patient ID's 81420, 81423, and 81427–81447)

Results

Clinical assessment of the study population

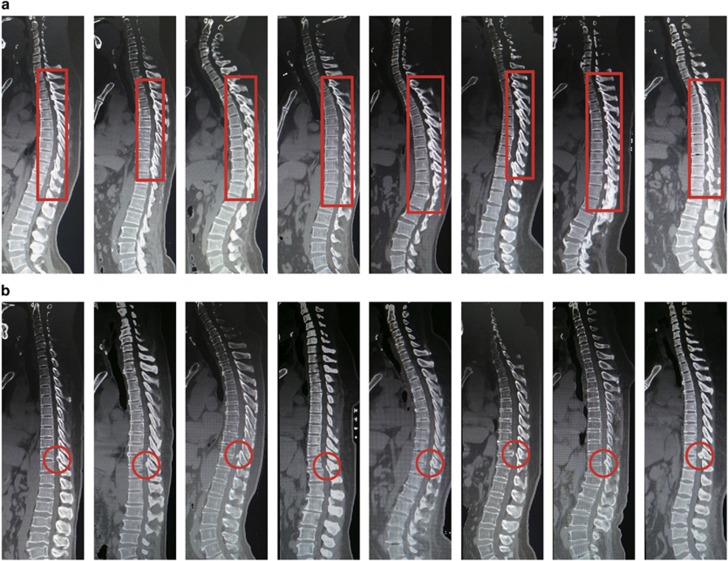

A total of 133 unrelated TOLF patients and 224 control patients were recruited for this study. All cases and controls were of Han Chinese ethnicity, from Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shandong, and provinces in the northern China. TOLF patients were classified according to the severity of ossification based on radiographic findings: Group A patients had long regional (more than six continuous levels) OLF at the thoracic spine (Figure 1a); and Group B patients had localized (1–3 levels) OLF at the thoracolumbar spine (Figure 1b). A summary of demographic and radiographic information is presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography of representative patients from two TOLF groups (a) Group A; (b) Group B. The red rectangle or circle shows the segments of ossification.

Table 1. Summary of non-genetic information from two TOLF groups and control patients.

| A | B | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 71 | 62 | 224 |

| Age (years) | 51.8±9.9 | 56.3±10.9 | 63.3±7.0 |

| Sex (M/F) | 42/29 | 37/25 | 129/95 |

| Number of ossified segments | 8.07±1.56 | 1.77±0.83 | — |

Whole-exome sequencing

Whole-exome sequencing was performed in 20 patients, 10 in each group. In total, we detected 7640 novel variants in the exonic and untranslated regions (UTR) of 5432 genes. These variants were not reported in the databases (the dbSNP and the 1000 Genomes Project). Thirty-nine variants in 29 genes were in the TGF-β superfamily or TGF-β/BMPs signaling pathway (Table 2). Most novel variants were detected in patients from Group A, including two missense variants in BMP-2 (NM_001200.3) exon region, c.460C>G:p.(R154G) (Novo 1) and c.584G>T:p.(R195M) (Novo 2). The two variants were further confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Figure 2a).

Table 2. Novel variants in genes in TGF-β superfamily or on TGF-β/BMPs signaling pathway.

| Patient no | Chr | POS | REF | ALT | Gene | Func | NCBI reference | UCSC links | cDNA change | Protein change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 1 | 226075436 | C | G | LEFTY1 | UTR3 | NM_020997.3 | uc009xej.2 | c.*22G>C | |

| 2 | 33173999 | G | A | LTBP1 | Exonic | NM_206943.2 | uc021vft.1 | c.552G>A | p.(=) | |

| 2 | 33174000 | A | T | LTBP1 | Exonic | NM_206943.2 | uc021vft.1 | c.553A>T | p.(R185W) | |

| 19 | 41114186 | G | A | LTBP4 | Exonic | NM_003573.2 | uc002ooh.1 | c.1418G>A | p.(R473H) | |

| A2 | 6 | 55739193 | G | A | BMP5 | Exonic | NM_021073.2 | uc011dxf.2 | c.471C>T | p.(=) |

| 12 | 53823598 | C | T | AMHR2 | UTR3 | NM_020547.2 | uc031qhl.1 | c.*352C>T | ||

| 14 | 74971826 | C | T | LTBP2 | Exonic | NM_000428.2 | uc001xqa.3 | c.4229G>A | p.(R1410H) | |

| 14 | 75017772 | C | T | LTBP2 | Exonic | NM_000428.2 | uc001xqa.3 | c.1681G>A | p.(G561R) | |

| A3 | 6 | 7727580 | C | T | BMP6 | Exonic | NM_001718.4 | uc003mxu.4 | c.392C>T | p.(S131F) |

| A4 | 2 | 121103962 | G | A | INHBB | Exonic | NM_002193.2 | uc002tmn.2 | c.198G>A | p.(=) |

| 16 | 3786691 | A | T | CREBBP | Exonic | NM_004380.2 | uc002cvv.3 | c.4820T>A | p.(L1907Q) | |

| A5 | 2 | 33623477 | G | C | LTBP1 | Exonic | NM_206943.2 | uc021vft.1 | c.5031G>C | p.(K1677N) |

| 6 | 19838010 | C | T | ID4 | Exonic | NM_001546.3 | uc003ncw.4 | c.25C>T | p.(P9S) | |

| A6 | 1 | 92327108 | C | T | TGFBR3 | UTR5 | NM_001195684.1 | uc001doj.3 | c.-20G>A | |

| 13 | 37446880 | G | A | SMAD9 | Exonic | NM_001127217.2 | uc010tep.2 | c.585C>T | p.(=) | |

| 18 | 18533644 | T | A | ROCK1 | Exonic | NM_005406.2 | uc002kte.3 | c.3956A>T | p.(N1319I) | |

| A7 | 2 | 69093687 | C | T | BMP10 | Exonic | NM_014482.1 | uc002sez.1 | c.351G>A | p.(=) |

| 15 | 66996228 | C | G | SMAD6 | Exonic | NM_005585.4 | uc002aqf.3 | c.632C>G | p.(A211G) | |

| 16 | 3779205 | G | A | CREBBP | Exonic | NM_004380.2 | uc002cvv.3 | c.5843C>T | p.(P1948L) | |

| 20 | 6759005 | C | G | BMP2 | Exonic | NM_001200.3 | uc002wmu.1 | c.460C>G | p.(R195M) | |

| A8 | 4 | 96052611 | A | G | BMPR1B | Exonic | NM_001203.2 | uc031sgm.1 | c.1024A>G | p.(K342E) |

| A9 | 1 | 40253904 | G | A | BMP8B | Exonic | NM_001720.3 | uc001cdz.1 | c.254C>T | p.(A85V) |

| 3 | 184104344 | T | G | CHRD | Exonic | NM_003741.2 | uc003fov.3 | c.1997T>G | p.(V666G) | |

| 15 | 66996117 | C | T | SMAD6 | Exonic | NM_005585.4 | uc002aqf.3 | c.521C>T | p.(T174I) | |

| 20 | 35675523 | T | C | RBL1 | Exonic | NM_002895.2 | uc002xgi.3 | c.1538A>G | p.(Y513C) | |

| 20 | 35684615 | C | T | RBL1 | Exonic | NM_002895.2 | uc002xgi.3 | c.1297G>A | p.(G433R) | |

| A10 | 2 | 203420027 | T | C | BMPR2 | Exonic | NM_001204.6 | uc002uzf.4 | c.1639T>C | p.(S547P) |

| 19 | 2249330 | C | T | AMH | UTR5 | NM_000479.3 | uc002lvh.2 | c.-2C>T | ||

| 20 | 6759129 | G | T | BMP2 | Exonic | NM_001200.3 | uc002wmu.1 | c.584G>T | p.(R195M) | |

| B2,B8 | 1 | 40240691 | C | T | BMP8B | Exonic | NM_001720.3 | uc001cdz.1 | c.354G>A | p.(=) |

| B3 | 1 | 52704025 | C | T | ZFYVE9 | Exonic | NM_007324.2 | uc001cto.4 | c.936C>T | p.(=) |

| 2 | 220437109 | C | T | INHA | Exonic | NM_002191.3 | uc002vmk.2 | c.13C>T | p.(=) | |

| 8 | 30643492 | A | G | PPP2CB | UTR3 | NM_001009552.1 | uc003xik.3 | c.*259T>C | ||

| B4 | 4 | 146463797 | C | T | SMAD1 | Exonic | NM_005900.2 | uc003ikc.3 | c.722C>T | p.(P241L) |

| 11 | 65318943 | C | T | LTBP3 | Exonic | NM_021070.4 | uc001oej.3 | c.1551G>A | p.(=) | |

| B5 | 2 | 11332728 | A | C | ROCK2 | Exonic | NM_004850.3 | uc002rbd.1 | c.3798T>G | p.(=) |

| 19 | 18899676 | A | G | COMP | Exonic | NM_000095.2 | uc002nkd.3 | c.575T>C | p.(V192A) | |

| B9 | 16 | 3807954 | G | A | CREBBP | Exonic | NM_004380.2 | uc002cvv.3 | c.3465C>T | p.(=) |

| 19 | 2251182 | C | A | AMH | Exonic | NM_000479.3 | uc002lvh.2 | c.909C>A | p.(=) |

The reference sequence was human reference genome (GRCh37/hg19) from National Center for Biotechnology Information; No variants were identified in B1, B6, B7, and B10.

Figure 2.

Analysis of BMP-2 variants in patients with TOLF. (a) Sequences showing two novel variants in BMP-2 (c.C460G:p.R154G, c.G584T:p.R195M), as compared with wild-type sequences. (b and c) Clustal W alignments showing conservation of mutated nucleotide (b) and amino acid (c) sequences.

Variation predictions and conservation analysis

To investigate whether the two BMP-2 variants would cause significant alteration to gene and protein expression, we applied a number of bioinformatics tools. A comparison of the nucleotide and amino acid sequences of BMP-2 orthologs showed that nucleotides at positions 460, 584 and amino acids at positions 154, 195 were fully conserved (Figure 2b and c). In addition, in silico analyses of the missense variants were conducted to predict their functional effects (Table 3). All five prediction tools identified the two novel variants as risk factors for disease.

Table 3. In silico analyses of two novel variants.

| SNPs | Sequence alterationa | PolyPhen-2 (SCOREb) | SIFT (SCOREc) | PROVEAN (SCOREd) | Mutation taster (P-valuee) | Mutation assessor (SCOREf) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Novo 1 | c.460C>G:p.(R154G) | Probably damaging (1.000) | Damaging (0.015) | Deleterious (−4.60) | Disease causing (0.999) | Medium (2.935) |

| Novo 2 | c.584G>T:p.(R195M) | Probably damaging (1.000) | Damaging (0.000) | Deleterious (−4.76) | Disease causing (0.999) | Medium (3.185) |

The reference sequence was human reference genome (GRCh37/hg19) from the National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Scores range from 0 to 1, with high scores being assigned to damaging variants.

Cutoff=0.05. Amino acid substitutions are predicted to be damaging if ≤0.05 and tolerated if >0.05.

Cutoff=−2.5. Amino acid substitutions are predicted to be damaging if ≤−2.5 and tolerated if >2.5.

Values close to 1 indicate a high predictive value. The P-value is not the probability of error as used in t-test statistics.

Cutoff=1.938. Amino acid substitutions are predicted to be non-functional (neutral to low) if ≤1.938 and functional (medium to high) if >1.938.

Genotyping

The two novel BMP-2 variants were identified in six other patients in Group A; four with the c.460C>G and two with the c.584G>T. Neither of the two novel variants were found in Group B or control patients.

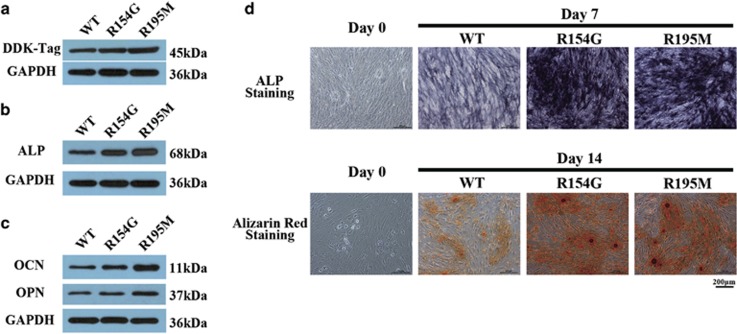

Functional assays of two BMP-2 variants

Western blot analysis of DDK-tag expression was used to quantify BMP-2 expression in transfected wild-type (WT) and mutant BMP-2 mouse pre-osteoblast (MC3T3-E1) cell lines (Figure 3a). BMP-2 expression in the two cell lines transfected with the novel variants were higher than in the WT line.

Figure 3.

Functional assays of wide-type and mutant BMP-2 transfected into MC3T3-E1 cells. (a) Exogenous BMP-2 expression as detected using the DDK-tag in different transfected cell lines. (b and c) Expression of osteogenic markers in different transfected cell lines at defined time points: ALP at day 7 (b); OCN and OPN at day 14 (c). (d) Staining for ALP activity at day 7 (upper) and alizarin red staining at day 14 (lower) in different transfected cell lines (scale bars represent 200 μm).

To determine the osteogenic differentiation capacity of cells transfected with WT or mutant BMP-2 after induction, the osteogenic differentiation was assessed by osteogenic markers expression (Figure 3b and c) and mineralization staining (Figure 3d). The two mutant BMP-2 transfected cells expressed significantly upregulated levels of ALP at day 7 and OCN, OPN at day 14. Meanwhile, mutant BMP-2-transduced cells also showed an increase in deposition of ALP staining on day 7 and Alizarin red staining on day 14.

Discussion

TOLF is a disease of the elderly and is relatively uncommon. However, it is a major cause of thoracic spinal myelopathy in East Asian populations, in contrast to Western populations.3, 27, 28 Kudo et al29 found that cells from the OPLL continuous-type group had higher osteogenic differentiation capacity than cells from an OPLL segmental-type group, with genetic background differences existing between the two groups. Similarly, we proposed that, in contrast with short segment ossification localized to the thoracolumbar region, a wider distribution of ossification at the thoracic spine may be attributed to underlying genetic factors. Scholars have suggested that inclusion criteria with more severe phenotypes could facilitate a genomic study on disease susceptibility genes by organizing more genetically homogeneous groups.6 To the best of our knowledge, there is no consensus on a universal classification system for TOLF. We selected two groups of patients (long regional at the thoracic spine and localized at the thoracolumbar) with typical radiological findings of TOLF. Such approach may exclude patients with other types of TOLF (eg, localized at middle thoracic or uncontinuous) but allows delineation of genetic variants associated with the disease. In addition, the average age of onset for TOLF is approximately 50 years; therefore, we recruited controls over 55 year of age to minimize confounding bias from patients who might develop the disease later.

The largest family of developmental polypeptide growth factors is the TGF-β superfamily that includes over forty human genes encoding for biologically important proteins such as activins, inhibins, BMPs, and growth differentiation factors (GDFs), TGF-β isoforms, and glial cell-derived factors.30 TGF-β/BMPs signaling pathway regulates cell differentiation, proliferation via multiple mechanisms and controls embryonic development, organogenesis, and adult organ homeostasis.31 In this study, we detected 39 variants in 29 genes in the TGF-β superfamily or TGF-β/BMPs signaling pathway using whole-exome sequencing. At least one variants was found in each patient in the Group A and most of the variants identified in Group A was missense. These results further indicated that long segment TOLF may be attributed to underlying genetic factors. Also, these identified gene may be involved in the TOLF pathologic process, but the exact mechanism needs more investigations.

The BMP-2 gene, located on chromosome 20p, consists of three exons. Exon 1 comprises a 5′-untranslated region and exon 2 contains a hydrophobic leader sequence followed by 118 amino acids. Exon 3 encodes 283 amino acids, of which the terminal 114 amino acids give rise to the mature protein.20 BMP-2 is a member of the TGF-β superfamily, which has important roles in skeletal development and bone formation. Recombinant BMP-2 has been shown to enhance the osteoblastic characteristics of osteoblast-like cells, as well as ligament cells from the posterior longitudinal ligament and ligamentum flavum.32, 33, 34, 35, 36 Histopathological studies have also found significant increase in expression of BMP-2 in the ossification area of OLF and OPLL.37, 38, 39, 40 So we next specifically focus on BMP-2 variants in TOLF patients.

In this study, we found two novel BMP-2 variants in two patients from the same classification (Group A). Six other patients from the same group were also identified to carry the same novel variants by Sanger sequencing. We did not identify either of these variants in Group B or in control patients. This observation suggests that these novel variants may be contributing to the pathophysiology of long segment TOLF.

The nucleotide substitutions associated with the BMP-2 variants identified in this study may impact gene expression through alterations to RNA folding and the BMP-2 protein tertiary structure. Li et al41 demonstrated that the p.(S37A) and p.(R190S) variants in BMP-2 increased BMP-2 expression in the osteogenic condition. To assess the pathogenic potential of the two variants, we transfected MC3T3-E1 mouse pre-osteoblast cells with vectors that encoded wild-type BMP-2 (WT) and the two variants. We demonstrated that the presence of heterozygous candidate variants in these mutants led to increased expression of BMP-2 protein, suggesting that these two variants may enhance osteogenic differentiation.

ALP, OCN, and OPN are widely recognized as specific indicators of osteogenic differentiation.42 In this study, expression of mutated BMP-2 increased osteogenic marker gene expression and promoted osteogenic differentiation. These results suggest that upregulation of BMP-2 expression caused by a single-nucleotide substitution could be one mechanism affecting the osteogenic differentiation of ligamentum flavum cells in TOLF patients.

In summary, TOLF is a disease with a genetic susceptibility component, especially in patients with long segment disease. We identified two novel variants in the BMP-2 gene in patients with TOLF among the Han Chinese population. Functional studies provide evidence that these variants upregulated BMP-2 expression and promoted osteogenic differentiation. We propose the association of BMP-2 as a susceptibility genetic factor in the pathogenesis of TOLF.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the patients for providing blood samples and specimens. We acknowledge the assistance of Beijing Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd (http://www.novogene.com) with exon sequencing and Beijing Ubiolab Technology Co., Ltd (http://www.ubiolab.com/) with Sanger sequencing. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81272031, 81071505).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Feng FB, Sun CG, Chen ZQ: Progress on clinical characteristics and identification of location of thoracic ossification of the ligamentum flavum. Orthop Surg 2015; 7: 87–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou X, Sun C, Liu X et al: Clinical features of thoracic spinal stenosis-associated myelopathy: a retrospective analysis of 427 cases. Clin Spine Surg 2016; 29: 86–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang N, Yuan HS, Wang HL et al: Epidemiological survey of ossification of the ligamentum flavum in thoracic spine: CT imaging observation of 993 cases. Eur Spine J 2013; 22: 857–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Q, Ma X, Li F et al: COL6A1 polymorphisms associated with ossification of the ligamentum flavum and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007; 32: 2834–2838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhao Y, Chen Y, Shi G, Yuan W: RUNX2 polymorphisms associated with OPLL and OLF in the Han population. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468: 3333–3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasugi T, Nakajima M, Ikari K et al: A genome-wide sib-pair linkage analysis of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. J Bone Miner Metab 2013; 31: 136–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JR, Patel AA, Brodt ED, Dettori JR, Brodke DS, Fehlings MG: Genetics and heritability of cervical spondylotic myelopathy and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: results of a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013; 38: S123–S146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horikoshi T, Maeda K, Kawaguchi Y et al: A large-scale genetic association study of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. Hum Genet 2006; 119: 611–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Ikari K, Furushima K et al: Genomewide linkage and linkage disequilibrium analyses identify COL6A1, on chromosome 21, as the locus for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. Am J Hum Genet 2003; 73: 812–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyasaka K, Kaneda K, Sato S et al: Myelopathy due to ossification or calcification of the ligamentum flavum: radiologic and histologic evaluations. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1983; 4: 629–632. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Deng C, Li YP: TGF-beta and BMP signaling in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Int J Biol Sci 2012; 8: 272–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsumaki N, Yoshikawa H: The role of bone morphogenetic proteins in endochondral bone formation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2005; 16: 279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou XF, Fan DW, Sun CG, Chen ZQ: Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2-induced ossification of the ligamentum flavum in rats and the associated global modification of histone H3. J Neurosurg Spine 2014; 21: 334–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya M, Harada A, Mizuno M, Iwata H, Yamada Y: Association between a polymorphism of the transforming growth factor-beta1 gene and genetic susceptibility to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in Japanese patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001; 26: 1264–1266, discussion 1266–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jekarl DW, Paek CM, An YJ et al: TGFBR2 gene polymorphism is associated with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. J Clin Neurosci 2013; 20: 453–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Yang ZH, Liu DM, Wang L, Meng XL, Tian BP: Association between two polymorphisms of the bone morpho-genetic protein-2 gene with genetic susceptibility to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine and its severity. Chin Med J (Engl) 2008; 121: 1806–1810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furushima K, Shimo-Onoda K, Maeda S et al: Large-scale screening for candidate genes of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. J Bone Miner Res 2002; 17: 128–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y, Liu ZZ, Feng J et al: Association of a BMP9 haplotype with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) in a Chinese population. PLoS One 2012; 7: e40587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Chang Z, Liu Y, Li YB, He BR, Hao DJ: A single nucleotide polymorphism in the human bone morphogenetic protein-2 gene (109T>G) affects the Smad signaling pathway and the predisposition to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013; 126: 1112–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Liu D, Yang Z et al: Association of bone morphogenetic protein-2 gene polymorphisms with susceptibility to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the spine and its severity in Chinese patients. Eur Spine J 2008; 17: 956–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ZQ, Sun CG: Clinical guideline for treatment of symptomatic thoracic spinal stenosis. Orthop Surg 2015; 7: 208–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R: Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009; 25: 1754–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R et al: A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet 2011; 43: 491–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H: ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38: e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X, Chen Z, Fan D, Sun C, Zeng Y: MiR-132-3p regulates the osteogenic differentiation of thoracic ligamentum flavum cells by inhibiting multiple osteogenesis-related genes. Int J Mol Sci 2016; 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu X, Chen Z, Fan D et al: Notch signaling pathways in human thoracic ossification of the ligamentum flavum. J Orthop Res 2016; 34: 1481–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon BJ, Kuh SU, Kim S, Kim KS, Cho YE, Chin DK: Prevalence, distribution, and significance of incidental thoracic ossification of the ligamentum flavum in Korean patients with back or leg pain: MR-Based Cross Sectional Study. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2015; 58: 112–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori K, Kasahara T, Mimura T et al: Prevalence, distribution, and morphology of thoracic ossification of the yellow ligament in Japanese: results of CT-based cross-sectional study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013; 38: E1216–E1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudo H, Furukawa K, Yokoyama T et al: Genetic differences in the osteogenic differentiation potency according to the classification of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011; 36: 951–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi M, Zhu J, Wang R et al: Latent TGF-beta structure and activation. Nature 2011; 474: 343–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas A, Heldin CH: The regulation of TGFbeta signal transduction. Development 2009; 136: 3699–3714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kon T, Yamazaki M, Tagawa M et al: Bone morphogenetic protein-2 stimulates differentiation of cultured spinal ligament cells from patients with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Calcif Tissue Int 1997; 60: 291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang IH, Kim H, Kwon UH et al: De novo osteogenesis from human ligamentum flavum by adenovirus-mediated bone morphogenetic protein-2 gene transfer. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005; 30: 2749–2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi K, Amizuka N, Sakou T, Kurokawa T, Ozawa H: Fibroblasts of spinal ligaments pathologically differentiate into chondrocytes induced by recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: morphological examinations for ossification of spinal ligaments. Bone 1997; 21: 155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Nagai E, Murata H et al: Involvement of bone morphogenic protein-2 (BMP-2) in the pathological ossification process of the spinal ligament. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001; 40: 1163–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon SH, Park SR, Kim H et al: Biologic modification of ligamentum flavum cells by marker gene transfer and recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004; 29: 960–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Ishidou Y, Yonemori K et al: Expression and localization of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) and BMP receptors in ossification of the ligamentum flavum. Bone 1997; 21: 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokosuka K, Park JS, Jimbo K et al: Immunohistochemical demonstration of advanced glycation end products and the effects of advanced glycation end products in ossified ligament tissues in vitro. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007; 32: E337–E339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato R, Uchida K, Kobayashi S et al: Ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine: histopathological findings around the calcification and ossification front. J Neurosurg Spine 2007; 7: 174–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yayama T, Uchida K, Kobayashi S et al: Thoracic ossification of the human ligamentum flavum: histopathological and immunohistochemical findings around the ossified lesion. J Neurosurg Spine 2007; 7: 184–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JM, Zhang Y, Ren Y et al: Uniaxial cyclic stretch promotes osteogenic differentiation and synthesis of BMP2 in the C3H10T1/2 cells with BMP2 gene variant of rs2273073 (T/G). PLoS One 2014; 9: e106598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Yan M, Wang Z et al: Effects of canonical NF-kappaB signaling pathway on the proliferation and odonto/osteogenic differentiation of human stem cells from apical papilla. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014: 319651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.