Abstract

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) is a persistent pain condition that remains incompletely understood and challenging to treat. Historically, a wide range of different outcome measures have been used to capture the multidimensional nature of CRPS. This has been a significant limiting factor in the advancement of our understanding of the mechanisms and management of CRPS.

In 2013, an international consortium of patients, clinicians, researchers and industry representatives was established, to develop and agree on a minimum core set of standardised outcome measures for use in future CRPS clinical research, including but not limited to clinical trials within adult populations

The development of a core measurement set was informed through workshops and supplementary work, using an iterative consensus process. ‘What is the clinical presentation and course of CRPS, and what factors influence it?’ was agreed as the most pertinent research question that our standardised set of patient-reported outcome measures should be selected to answer. The domains encompassing the key concepts necessary to answer the research question were agreed as: pain, disease severity, participation and physical function, emotional and psychological function, self efficacy, catastrophizing and patient's global impression of change. The final core measurement set included the optimum generic or condition-specific patient-reported questionnaire outcome measures, which captured the essence of each domain, and one clinician reported outcome measure to capture the degree of severity of CRPS. The next step is to test the feasibility and acceptability of collecting outcome measure data using the core measurement set in the CRPS population internationally.

1. Introduction

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) is a pain condition, usually affecting a single limb, which manifests in a wide range of sensory, motor, trophic and autonomic abnormalities [29]. Prospective studies indicate that most cases will resolve within 6-13 months [4]; however, 15-20% of individuals will develop a long-term disability, negatively affecting their quality of life [21,26]. In recent years, revised diagnostic and research criteria have been published, resulting in improved standardisation across study participants [29]. Currently, however, there is no internationally agreed upon standardised core measurement set for CRPS clinical research studies in adult populations. This has limited the synthesis of clinical research evidence and consequently impeded the understanding of CRPS and potential therapeutic interventions [41,59]. Due to the multidimensional nature of the condition, CRPS clinical studies currently use a diverse range of questionnaire outcome measures [28]. Furthermore, CRPS has recently been categorised as an ’orphan disease’ by the US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency, on the basis that fewer than 200,000 people in the US, and fewer than 154,000 people in the European Union, are affected each year [20,57]. This further highlights the importance of conducting multi-centre collaborative projects to help achieve sufficient sample sizes for meaningful clinical studies.

The development of a core measurement set would facilitate the pooling and comparison of data to answer specific research questions agreed upon as internationally important and relevant for the advancement of CRPS treatment. Recommending the use of the core measurement set within all clinical research studies would enable these identified research questions to be answered in an optimal and timely manner.

A core outcome measurement set can be defined as an agreed upon, standardised set of outcomes, which should be measured and reported in all clinical trials in a particular condition [61]. In recent years, core measurement sets have been increasingly developed in many health conditions in response to the inconsistency of outcome measures used in clinical trials investigating the same disease or condition [8,25]. Utilisation of a core measurement set would reduce heterogeneity and thereby facilitate the reporting of a complete and consistent set of outcome measures across studies [55].

Previous initiatives have advocated the use of core outcome measurement sets in pain and rheumatology clinical trials: Initiative on Methods Measurement and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) [17] and Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) [24]. This provided a starting point for our work, due to a degree of overlap between these disorders and CRPS. The complexity and multifactorial nature of CRPS, however, necessitated the development of a core measurement set specific to this condition. Furthermore, due to the relatively low incidence of CRPS, we wished to broaden the relevance of our core set to encompass all clinical research studies, not exclusive to, but including clinical trials, so as to optimise our ability to create large study populations by combining multi-centre data sets.

This paper will present the first internationally agreed core measurement set recommended for use in CRPS clinical research.

2. Methods

2.1. The consortium

An international consortium was established in 2013, under the auspices, and with the support of the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) CRPS Special Interest Group, to agree upon a minimum core set of outcome measures recommended for use in all CRPS clinical studies, including clinical trials. The acronym COMPACT was agreed upon and adopted by the consortium to represent the initiative and the resultant core measurement set. COMPACT initally represented ‘Core Outcome Measures for complex regional PAin syndrome Clinical Trials’. However, through preparation of this manuscript, and Reviewers’ feedback, it was agreed by the consortium that as we are recommending this core set as appropriate for use in all clinical research studies, not exclusively for trials, then ‘Core Outcome Measures for complex regional PAin syndrome Clinical sTudies’ was a more appropriate title for this core set.

The consortium comprised CRPS patients, clinicians, researchers and industry representatives from fifteen countries: Switzerland, Germany, the Netherlands, Canada, United States, Denmark, Norway, Israel, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Japan, Argentina, Brazil and United Kingdom. Members were recruited from the global CRPS community via an email invitation. Members included those with clinical or research expertise in CRPS from within an academic or clinical setting and/or an interest in treatment outcome measures.

Patient representatives were recruited via support groups representing the UK, Netherlands and Switzerland. The inclusion of patient representatives, within our research team, was considered essential to ensure the core measurement set included outcome measures that were important to those with CRPS and pertinent to their experience of the condition. Kirwan et al.(2003) [35] described the value of this and the benefit of seeking a patient’s perspective to gain understanding of the terms used within the outcome measures. Patient involvement, as active collaborators, contributes to the development of credible patient-reported outcome measures, which are embedded in the patient experience [51].

Since being established in May 2014, the CRPS International Research Consortium (IRC), an organisation facilitating the pooling of resources for timely and conclusive studies (www.crpsconsortium.org), has supported COMPACT by encouraging links with other researchers. In addition, researchers wishing to use the core measurement set will be able to access it via the IRC, thereby monitoring utilisation and version control.

2.2. Ethical approval and funding

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of the West of England, Bristol, UK. The Royal United Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Bath, UK provided sponsorship. Funding was received from the Balgrist Foundation, Switzerland and the Dutch National CRPS Patient Organization.

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. The workshops

Four workshops (W) (range 15-27 attendees) were convened between November 2013 and August 2015.

W1 was held in November 2013, Bath, UK (n= 27)

W2 - May 2014, Chicago, USA (n= 15)

W3 - January 2015, Bath, UK (n= 20)

W4 - August 2015, Zurich, Switzerland (n= 18)

Invitation to attend the workshops was extended to all members of the consortium, however attendance was limited by geographical location and availability of funding to attend (see supplementary information for list of attendees). The opportunity to contribute to supplementary work via email was open to all members. The COMPACT initiative was presented at the 15th World Congress of Pain in Buenos Aires in 2014 and to members of the International Association of the Study of Pain (IASP) CRPS Special Interest Group via regular newsletters. In keeping with recommendations for incorporating stakeholder input, Workshop 1 and 3 included representatives from the pharmaceutical industry, with specific expertise in chronic pain and clinical rheumatology trials [51]. The representation was from Grunenthal Ltd* (W1&3) and Pfizer Ltd (W1) recruited via an email invitation sent to industries working in the area of CRPS or pain.

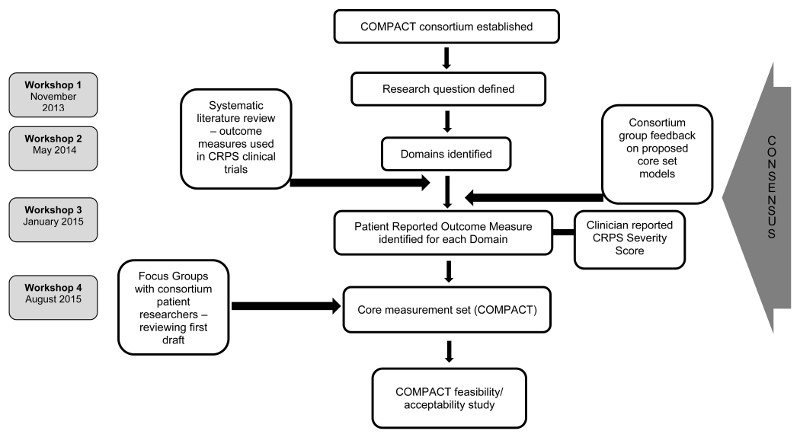

The four workshops followed a semi-structured format, (see supplementary information). Two of the authors (SG, CM) chaired the workshops and/or led discussions. Each workshop, by its nature, included scheduled timeframes, where attendees worked in small groups with a clear scope and goal. Group work was fed back to all attendees for further discussion. All decisions were agreed upon by majority consensus of those present at each workshop. Figure 1 depicts the development process.

Figure 1.

Development of a core measurement set for CRPS clinical research studies

2.3.2. The research question

Prior to W1, consortium members were asked to identify research questions they wished to address to advance the treatment of CRPS. For example, these could be in relation to the identification of risk factors for the development of, or the clinical course of the condition, both of which are yet to be firmly established in CRPS [58]. The first COMPACT workshop identified a research question which required international collaboration and pooling of data, and could not be investigated without a consistent data set. It was agreed the research question should cover three main purposes for measurement: classification (disease/no disease), effectiveness (change over time) and prognostic indicators.

The initial research question was agreed as:

‘What is the clinical presentation and course of CRPS and what factors influence it?’

Answering this question, will provide a better understanding of the potential phenotypes of CRPS, prognostic indicators, and methods of targeting therapeutic approaches. It is relevant within the context of both cross sectional and prospective studies, including cohort studies and comparative clinical trials. The question encompasses type 1 and type 2 CRPS, and is relevant across the disease trajectory.

2.3.3. Domains

The minimum number of domains, or key concepts, which were considered necessary to answer the research question, was agreed upon by consensus. These provided a framework or scope which then informed the selection of appropriate questionnaire outcome measures or instruments.The OMERACT and IMMPACT initiatives were presented at W1 identifying a number of core domains which should be considered when establishing a core set of health outcome measures [8,55]. A decision was made to use the IMMPACT core domains as a starting point, as these are recommended for chronic pain clinical trials [55] and are therefore highly applicable to CRPS, a chronic pain condition. However, in order to develop a robust core measurement set, a decision was made not to adopt these without confirming their applicability to CRPS, a condition somewhat unique in its features and life impacts. Both IMMPACT and OMERACT recommend particular domains which should be considered in condition-specific clinical trials [8,55]. The domains should be appropriate for the population under investigation, measure positive and negative outcomes and match the purpose of the clinical trial [55]. With this in mind, the consortium chose to identify CRPS specific domains rather than directly adopt those previously identified for generic chronic pain or rheumatology studies.

2.3.4. Measurement tools

Selection of questionnaire outcome measures was agreed by consensus and informed by: 1) a systematic literature review conducted by members of the consortium [28], 2) a core data set used by a pre-existing Dutch clinical and academic CRPS research consortium (TREND), and 3) patient burden. The heterogeneity of outcome measures, which was apparent from the systematic review [28], demonstrated the challenge of synthesising research evidence at an international level and even nationally. Emphasis was placed on identifying the minimum number of outcome measures (and the briefest possible), which would permit reliable assessment of the core domains, as the intention is for individual researchers to augment the core measurement set with measures specific to their investigation. A number of different questionnaires were considered for inclusion in the core measurement set (see supplementary information), many of which were identified from the systematic literature review [28]. A questionnaire was considered based on its ability to capture the key aspects of each domain, its length and experience of its use by the workshop attendees.

Consideration was given to the development of new instruments, however, due to the time and resource required for this, existing instruments were first examined for suitability. A systematic review of the literature, which evaluated the psychometric properties of outcome measures used for CRPS, found no tool to have been fully assessed in this population [44], and no specific tool was recommended for use in CRPS [44]. This is based on prior CRPS specific validation, with the exception of the CRPS Severity Score [30].

In addition to hard copy questionnaire outcome measures, including those identified as a result of the literature review, consideration was also given to an electronic patient-reported outcome measurement information system (see 2.3.5).

The measures agreed upon at W4 primarily comprised patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), measuring various aspects of health and function identified as important to the CRPS patient and applicable to the research question. The only addition to these PROMs was a clinican reported outcome measure to describe the severity of the condition. In the interests of time and resources, the consortium did not conduct a review of objective clinical outcome measures, for example thermal imaging to record temperature change or volumetric data to measure oedema, though we recognise the important contribution of these types of measures in CRPS clinical research. This work is planned to be conducted in the near future under the auspices of the IRC and IASP CRPS Special Interest Group.

2.3.5. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®)

W2 and W3 considered the potential of using an existing item bank of patient reported outcome measures: Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) [13]. This is a National Institute of Health (USA) funded system, which provides psychometrically sound and validated patient-reported outcome measures that can be used in a wide range of chronic conditions. PROMIS is comprised of calibrated item banks to measure diverse health concepts such as pain, physical function and depression; these are presented for each domain as individual items and/or instruments of various lengths. In addition, PROMIS includes several collections of items, termed profiles, which measure multiple domains. For example, the PROMIS-29 profile assesses 7 domains, each with 4 questions; depression, anxiety, physical function, pain interference, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and ability to participate in social roles and activities [13]. There is also an additional numeric pain intensity 0-10 rating scale (NPRS).

The PROSETTA Stone initiative [14] has enabled results obtained using PROMIS items to be directly compared with many standard instruments currently employed in clinical trials, such as the SF-36 or Brief Pain Inventory. Data collection using the PROMIS item bank can be captured electronically on a secure server or alternatively using a paper version. Importantly, all instruments are freely available in the public domain and work is underway for translation and cultural validation of the profiles in multiple languages.

2.3.6. Modelling of the Core Measurement Set (COMPACT)

To inform COMPACT, three models, comprising standard patient-reported outcome measures, were constructed and disseminated electronically, for consideration by the consortium. The three models were presented at the meeting of the IASP CRPS Special Interest Group in Buenos Aires in 2014. Feedback was collated and presented at W3. Following consultation with colleagues familiar with PROMIS, a fourth model was constructed which consisted largely of PROMIS items. Feedback was collected from individuals with CRPS (n=5) regarding the patient burden and ease of understanding and completion of the various questionnaire models. These individuals were naïve to the development of the questionnaire, were not members of the consortium and were native English speakers. All four models and the patient feedback were presented at W3.

After W3, the final draft COMPACT was presented to a UK based focus group of patient researchers (n=3). The design of the document was reviewed in detail on two occasions, to allow revisions to be considered and then the feedback was presented to the consortium at W4. Care was taken to assess the COMPACT measures for cultural and gender sensitivity, for example, ‘gardening’ was given as an alternative to ‘yard work’ and the date within the document was internationally formatted. The final COMPACT was agreed upon by consensus at W4.

3. Results

3.1. Core Outcome Measures for complex regional PAin syndrome Clinical sTudies (COMPACT)

The following outcome measures comprise COMPACT (Table 1). The domains reported in Table 1, closely reflect those recommended by IMMPACT [55], with the addition of disease severity, catastrophizing and self-efficacy. The outcome measures comprising COMPACT are introduced throughout the document with text designed to ensure the respondent focuses on only those factors relevant to CRPS. For example, ‘the following questions ask you about the type of pain you experience due to CRPS’. Respondents are asked to reflect on a specific time frame, for example ‘in the past 7 days.’

Table 1.

Patient-reported outcome measures included in COMPACT

| Domain | Outcome Measure | Construct |

|---|---|---|

| Participant characteristics | Gender, affected limb, limb dominance prior to CRPS, CRPS duration, participation in employment/education/voluntary work | Demographic data |

| Pain | Numeric Rating Scale and PROMIS 29 Profile (version 2)[13] | Pain intensity: average, worst, least |

| Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire SF-MPQ-2 [18] | Six neuropathic pain items | |

| PROMIS 29 Profile (version 2) [13] | Pain interference. | |

| EQ-5D-5L [32] | Health state comprising mobility, self care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression. | |

| Disease severity | CRPS Severity Score [30] | Severity of CRPS |

| CRPS symptom questions | Experience of CRPS | |

| Participation and physical function. | PROMIS 29 Profile (version 2) | Physical function, social participation |

| EQ-5D- 5L | See above | |

| Emotional and psychological function | PROMIS 29 Profile (version 2) | Anxiety, depression, fatigue, sleep |

| PROMIS suicidal ideation question [45] | Suicidal ideation | |

| EQ-5D- 5L | See above | |

| Catastrophizing | Pain Catastrophizing Scale [53] | Pain catastrophizing |

| Self efficacy | Pain Self-efficacy Questionnaire [40] | Self-efficacy |

| Patient's global impression of change | Patient Global Impression of Change# | Change in CRPS from baseline |

To be completed at T2 only

3.1.1. Pain

Pain is an overarching feature of CRPS [37] and consequently should be assessed in any CRPS clinical study. A recent, international Delphi study (n=252), which asked people with CRPS to define their top five priorities for recovery supported this, identifying the top two priorities as no further CRPS related pain in their limb(s) and no generalised pain [38]. The dimensions of pain intensity and pain interference were considered essential for inclusion in the core measurement set in order to distinguish between potential sub-types of the condition. Pain intensity is most commonly used as the primary outcome measure for studies investigating chronic pain interventions [17]. When comparison is made between multiple pain ratings and a single pain rating, the latter has been demonstrated to be an accurate predictor of average pain for those with CRPS type 1 [22]. The authors therefore recommend CRPS pain be rated as the average over the last seven days using an item from the PROMIS 29 profile, version 2.0 [13]. A numeric rating scale will be used to measure the least and worst pain in the previous 24 hours, to capture the daily variability in its intensity. Pain interference will be measured using the four items within the PROMIS 29 profile, version 2.0 [13].

There is evidence that pain qualities (eg., burning, cramping, throbbing pain) do change over the course of CRPS [49] and therefore capturing the nature of pain qualities was also considered important with regard to identifying potential CRPS sub-types and assessing the variability of pain over time. Treatment interventions may be more effective for some pain qualities [17]. Pain qualities will be captured using the neuropathic items from the McGill Pain Questionnaire-2 (SF-MPQ-2) [18]. Permission was obtained from the author, to administer the six quality measures in isolation from the full version of the SF-MPQ-2. A number of questionnaire outcome measures were considered to capture this aspect of pain (see Table 1) however, the six SF-MPQ-2 neuropathic items capture the essential qualities with minimum patient burden. A preliminary Rasch analysis supported the use of this sub-scale as a ‘stand-alone’ assessment [42] however, this needs to be repeated in a larger, mixed population.

Research shows that some people with CRPS experience widespread pain [7], which could confound the assessment of CRPS related pain. For this reason, the individual will be asked to consider and report only the pain related to the CRPS when completing the instrument. The consortium patient researchers recommended the pain measurement tools should not be listed first within the COMPACT questionnaire set. This was judged to have the potential to place excessive focus on the pain and the negative connotations associated with this.

3.1.2. Disease severity score

Disease severity, measured using the CRPS Severity Score (CSS) [30], is completed by the clinician at baseline. The CSS is directly derived from the Budapest CRPS diagnostic criteria and will confirm the CRPS diagnosis [29]. Any clinician can complete the CSS and no special training is required. In addition it will provide information regarding differences in clinical presentation between individuals [10,16] and the investigation of possible subtypes of the condition. Symptoms reported by the individual and CRPS signs present on examination, are recorded by the clinician. Higher scores indicate greater CRPS severity (range 0-16) [31]. In addition to baseline, completion of the CSS at a minimum of one of the additional time points of 3, 6 and 12 months are recommended if possible. Completion on more than one occasion will enable the changing clinical aspects of CRPS over time to be captured for each individual. The CSS has been found to be responsive (Effect Size 1.99 [95% Confidence Interval 1.54-2.44], Standardized Response Mean =1.42) in a sample of n=66 persons with CRPS followed for one year [43].

3.1.3. Participation and Physical Function

Reduced function as a consequence of pain is apparent in individuals with CRPS [6]. Of these, approximately 15% will report unremitting pain and physical impairment two years after the onset of CRPS [21,48]. This is supported by a recent systematic review, which found functional impairments such as weakness, stiffness and limited range of motion persisted in the majority of patients for one year or more in varying severity [4].

Social participation was considered important to measure; both in relation to the limitations which may result from physical impairment but also social avoidance in order to prevent any accidental contact with the affected limb [47]. COMPACT will capture measures of physical function and social participation within the PROMIS 29 profile and the EQ-5D-5L, the latter used widely, allowing comparison across chronic conditions. The PROMIS 29 profile will also measure the constructs of fatigue and sleep quality, which may develop as a consequence of living with chronic pain [27]. Once again, the individual will be asked to consider and report how CRPS impacts on their life when completing the instrument, to reduce possible confounders related to comorbidities.

3.1.4. Emotional and Psychological Function

As a consequence of living with a long-term pain condition, psychological symptoms such as depression and anxiety may develop [27]. Although a systematic review identified no relationship between onset of CRPS type 1 and several psychological factors [5], some evidence suggests the intensity of CRPS pain may be uniquely impacted by psychological distress [3,9,11]. Patients with co-morbid chronic pain, depression and anxiety have been shown to have worse clinical outcomes than patients with pain alone [1,12]. This domain measures anxiety and depression using the PROMIS-29 profile. In addition, suicidal ideation will be assessed using a PROMIS item [36,45].

3.1.5. Self-efficacy

The Pain Self Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ) will be used to capture this domain [40]. The respondent considers how confident they are performing each activity, while taking their pain into account. This provides more clinically useful data than asking about performing an activity in isolation [40].

3.1.6. Catastrophizing

Pain catastrophizing was considered an important dimension of the core measurement set. Multiple studies in non-CRPS populations indicate catastrophizing is a prospective predictor of negative pain outcomes [19,23,46,50,54]. The authors recommend the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) be used to capture this domain [53]: a score of greater than 30 is thought to represent a problematic level of catastrophic thinking [52]. Bean et al. [2] reported the average PCS score at baseline was 22.0 in their sample of 66 persons diagnosed with CRPS within the previous 12 weeks, but underwent significant reduction to a mean score of 13.4 by 6 months as treatment progressed (p<0.001). This supports pain catastrophization as an important construct for measuring the evolution of this syndrome.

3.1.7. Patients Global Impression of Change

In order to establish the efficacy of interventions in CRPS clinical studies it was considered important to capture the patient's global impression of change. Respondents will be asked to rate the improvement of CRPS using a 7 point scale, ranging from “very much improved” to “very much worse” [33].

3.1.8. Demographic data and healthcare utilisation

COMPACT will include demographic data to capture the characteristics of the population such as gender, age, affected limb(s) and disease duration. Ability to participate in paid or unpaid employment and education will also be reported.

Health care utilisation was excluded from the final domains as it was considered more appropriate that individual countries adopt a local measure due to the variation in healthcare service systems. Reporting these data may also be affected by an individual’s ability to recall clinical interactions and may be influenced by litigious processes in some countries. Use of a country specific measure will more appropriately accommodate these cultural variations than a single generic tool.

4. Discussion

The international application of COMPACT will require availability in a wide range of languages. This was a consideration throughout the development process and informed the final selection of the outcome measures. Many of the selected measures are currently available in a number of translations, for example, the EQ-5D-5L [32] and Pain Catastrophizing Scale [53]. The PROMIS initiative has addressed translation and cultural validation for many of the PROMIS items, although further work is required for translation of the full range of languages required for COMPACT. Where documents require translation these will be undertaken by the COMPACT consortium research partners in each country under strict adherence to the requirements specified by the developers of each questionnaire or by adhering to the ‘best practice’ translation standards established in a protocol for the CRPS Recovery Study [39]. This uses a forwards and backwards translation approach to ensure the meaning of text is the same across each of the countries.

Whilst the measurement properties of the PROMIS tools are assumed to be invariant across populations [13], the proposed constellation of outcome measures included in COMPACT will require further work to ascertain their psychometric properties and develop relevant norms for the CRPS population. This will be undertaken after the feasibility and acceptability of COMPACT has been tested using data and views from the international CRPS community.

Future work will also include the development and validation of a paediatric version of COMPACT. The current version is designed for use in an adult population, although some of the measures have already been validated in children or have paediatric versions [15,60].

The authors recognise the importance of developing safe and effective data systems to support this work. The consortium will explore the feasibility of using an existing data management system for the central collection and management of the COMPACT data. This will facilitate data sharing, meta-analysis and will allow sub-group analyses, for example, gender-based differences and CRPS subtypes.

The authors recommend COMPACT to be completed by all patients at two time points, baseline and 6 months. At 3 months our patient population may have only just initiated treatment and rehabilitation, and a recent study demonstrated the greatest change in symptom severity was in the first 6 months following CRPS onset [2]. Draft guidance for studies evaluating analgesia in chronic pain recommend a study duration of at least 3 months [56]. Additional assessment at 3 and/or 12 months are optional, and the CSS should be completed at baseline as a minimum. These time points were considered appropriate for our specifc research question however, we recognise that these recommended time points may need adjusting, or adding to, to meet study specifc requirements.

A key challenge will be to raise awareness and dissemination of the core measurement set to promote its use by those conducting CRPS clinical studies. Kirkham et al. (2013) [34] identified that 60-70% of rheumatology clinical trials were reporting the full OMERACT core measurement set 20 years after its introduction. Future work will include a survey of health professionals within the international CRPS community to identify which outcome measures are currently being used and then to re-evaluate this after dissemination.

5. Conclusion

A core measurement set for CRPS clinical studies has been agreed upon by an iterative process of consensus. This will facilitate international collaborative studies to advance our knowledge and treatment of CRPS. The next step is to test the feasibility and acceptability of COMPACT in the international CRPS population, and to identify an appropriate electronic data management system. A workshop will be convened in 2018 to review data collected from studies using COMPACT, and users (patient and researchers) experience of COMPACT.

If researchers outside the COMPACT consortium wish to use COMPACT it can be accessed from relevant websites (eg. CRPS International Research Consortium, IASP CRPS Special Interest Group). It is asked that, if COMPACT is included in research studies, feedback is shared with the COMPACT consortium.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

C McCabe was funded by a National Institute for Health Research Career Development Fellowship (CDF/2009/02/). This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. This work was supported by The Balgrist Foundation, Balgrist University Hospital, Switzerland, and the Dutch National CRPS Patient Organization, Netherlands.

Footnotes

Opinions and views expressed by the representative from Grunenthal Ltd, were given as individual opinions, as an experienced employee within pharmaceutical industry, and not necessarily representative of Grunenthal Ltd as a whole.”

Conflict of Interest Statement

Professor Bruehl reports grants from NIH, personal fees from Thar Pharmaceuticals, personal fees from Grunenthal, personal fees from Eli Lilly, grants from Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy Syndrome Association, outside the submitted work. Professor R Perez has received government grants (Economic affairs, STW, ZonMw) and consultancy fees and has previously received research grants from Pfizer and Grünenthal. Professor C McCabe has previously received consultancy fees from GlaxoSmithKline and Grünenthal outside of this submitted work. Professor Birklein received grants from the German Research Foundation, unrestricted research support from Pfizer, Germany and Grünenthal, and consulting fees from Astellas and Eli Lilly, all outside the submitted work. Dr J Lewis has a National Institute for Health Research Clinical Lectureship. T Worth is an employee of Grunenthal Ltd.

References

- [1].Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and Pain Comorbidity: A Literature Review. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(20):2433–2445. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bean DJ, Johnson MH, Heiss-Dunlop W, Kydd RR. Extent of recovery in the first 12 months of complex regional pain syndrome type-1: A prospective study. Eur J Pain. 2016;20(6):884–894. doi: 10.1002/ejp.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bean DJ, Johnson MH, Kydd RR. Relationships between psychological factors, pain, and disability in complex regional pain syndrome and low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2014;30:647–53. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bean DJ, Johnson MH, Kydd RR. The outcome of complex regional pain syndrome type 1: A systematic review. J Pain. 2014;15(7):677–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.01.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Beerthuizen A, van 't Spijker A, Huygen FJ, Klein J, de Wit R. Is there an association between psychological factors and the Complex Regional Pain Syndrome type 1 (CRPS1) in adults? A systematic review. Pain. 2009;145(1–2):52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Birklein F, O'Neill D, Schlereth T. Complex regional pain syndrome: An optimistic perspective. Neurology. 2015;84(1):89–96. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Birley T, Goebel A. Widespread pain in patients with complex regional pain syndrome. Pain Practice. 2014;14(6):526–531. doi: 10.1111/papr.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Boers M, Kirwan JR, Wells G, Beaton D, Gossec L, d'Agostino MA, Conaghan PG, Bingham CO, III, Brooks P, Landewe R, March L, et al. Developing Core Outcome Measurement Sets for Clinical Trials: OMERACT Filter 2.0. J ClinEpidemiol. 2014;67(7):745–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bruehl S, Chung OY, Burns JW. Differential effects of expressive anger regulation on chronic pain intensity in CRPS and non-CRPS limb pain patients. Pain. 2003;104:647–54. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Bruehl S, Harden RN, Galer BS, Saltz S, Backonja M, Stanton-Hicks M. Complex regional pain syndrome: are there distinct subtypes and sequential stages of the syndrome? Pain. 2002;95(1–2):119–24. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00387-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bruehl S, Husfeldt B, Lubenow TR, Nath H, Ivankovich AD. Psychological differences between reflex sympathetic dystrophy and non-RSD chronic pain patients. Pain. 1996;67:107–14. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)81973-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Castro M, Quarantini LC, Daltro C, Pires-Caldas M, Koenen KC, Kraychete DC, Oliveira IRD. Comorbid depression and anxiety symptoms in chronic pain patients and their impact on health-related quality of life. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry (São Paulo) 2011;38(4):126–129. http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0101-60832011000400002&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, Gershon R, Cook K, Reeve B, Ader D, Fries JF, Bruce B, Matthias R, on behalf of the PROMIS cooperative group The Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): Progress of an NIH Roadmap Cooperative Group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45(5):S3–11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Choi SW, Podrabsky T, McKinney N, Schalet BD, Cook KF, Cella D. Vol. 1. Chicago, IL: Department of Medical Social Sciences, Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University; 2012. PROSetta Stone® Analysis Report: a Rosetta Stone for Patient Reported Outcomes. [accessed at http://www.prosettastone.org] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Crombez G, Bijttebier P, Eccleston C, Mascagni T, Mertens G, Goubert L, Verstraeten K. The child version of the pain catastrophizing scale (PCS-C): a preliminary validation. Pain. 2003;104(3):639–646. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].De Mos M, de Brujn AGJ, Huygen FJPM, Dielman JP, Stricker BHC, Sturkenboom MCJM. The incidence of complex regional pain syndrome” a population-based study. Pain. 2007;129(1.2):12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Katz NP, Kerns RD, Stucki G, Allen RR, Bellamy N, Carr DB, et al. Immpact. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113(1–2):9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Revicki DA, Harding G, Coyne KS, Peirce-Sandner S, Bhagwat D, Everton D, Burke LB, Cowan P, Farrar JT, et al. Development and initial validation of an expanded and revised version of the Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ-2) Pain. 2009;144(1–2):35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Edwards RR, Haythornthwaite JA, Smith MT, Klick B, Katz JN. Catastrophizing and depressive symptoms as prospective predictors of outcomes following total knee replacement. Pain Res and Manag. 2009;14:307–311. doi: 10.1155/2009/273783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].European Medicines Agency. Public summary of opinion on orphan designation: Zoledronic acid for the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome. 2013 www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/orphans/2013/10/human_orphan_001271.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac58001d12b.

- [21].Field J, Warwick D, Bannister GC. Features of algodystrophy ten years after Colles’ fracture. J Hand Surg. 1992;17(3):318–20. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(92)90121-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Forouzanfar T, Kemler M, Kessels AH, Köke AA, van Kleef M, Weber WJ. Comparison of multiple against single pain intensity measurements in complex regional pain syndrome type I: analysis of 54 patients. Clin J Pain. 2002;18(4):234–237. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200207000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Forsythe ME, Dunbar MJ, Hennigar AW, Sullivan MJ, Gross M. Prospective relation between catastrophizing and residual pain following knee arthroplasty: two-year follow-up. Pain Res Manag. 2008;13:335–41. doi: 10.1155/2008/730951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Fried BJ, Boers M, Baker PR. A method for achieving consensus on rheumatoid arthritis outcome measures: the OMERACT conference process. J Rheumatol. 1993 Mar;20(3):548–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gargon E, Gurung B, Medley N, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, Clarke M, Williamson PR. Choosing important health outcomes for comparative effectiveness research: a systematic review. PloS one. 2014;9(6):e99111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Geertzen JH, Dijkstra PU, van Sonderen EL, Groothoff JW, ten Duis HJ, Eisma WH. Relationship between impairments, disability and handicap in reflex sympathetic dystrophy patients: A long-term follow-up study. ClinRehabil. 1998;12:402–412. doi: 10.1191/026921598676761735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Goebel A, Barker CH, Turner-Stokes L, et al. Complex regional pain syndrome in adults: UK guidelines for diagnosis, referral and management in primary and secondary care. London: RCP; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Grieve S, Jones L, Walsh N, McCabe C. What outcome measures are commonly used for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome clinical trials? A systematic review of the literature. Eur J Pain. 2015;20(3):331–340. doi: 10.1002/ejp.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Harden RN, Bruehl S, Perez RSGM, Birklein F, Marinus J, Maihofner C, Lubenow T, Buvanendran A, Mackey S, Graciosa J, Mogilevski M, et al. Validation of proposed diagnostic criteria (the "Budapest Criteria") for Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. Pain. 2010;150(2):268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Harden RN, Bruehl S, Perez RSGM, Birklein F, Marinus J, Maihofner C, Lubenow T, Buvanendran A, Mackey S, Graciosa J, Mogilevski M, et al. Development of a severity score for CRPS. Pain. 2010;151(3):870–876. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Harden N, Maihofner C, Abousaad E, Vatine J-J, Kirsling A, Perez RSGM, Kuroda M, Brunner F, Stanton-Hicks M, Mackey S, Birklein F, et al. Changes in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) Features Over Time: Prospective Validation of the CRPS Severity Score (CSS) Paper in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen M, Kind P, Parkin D, Bonsel G, Badia X. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L) Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1727–1736. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kamper SJ, Maher CG, Mackay G. Global Rating of Change Scales: A Review of Strengths and Weaknesses and Considerations for Design. J Man Manip Ther. 2009;17(3):163–170. doi: 10.1179/jmt.2009.17.3.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kirkham J, Boers M, Tugwell P, Clarke M, Williamson PR. Outcome measures in rheumatoid arthritis randomised trials over the last 50 years. Trials. 2013;14:324. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kirwan J, Heiberg T, Hewlett S, Hughes R, Kvien T, Ahlmèn M, Boers M, Minnock P, Saag K, Shea B, Suarez Almazor M, et al. Outcomes from the Patient Perspective Workshop at OMERACT 6. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(4):868–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lee DH, Noh EC, Kim YC, Hwang JY, Kim SN, Jang JH, Byun MS, Kang DH. Risk factors for suicidal ideation among patients with complex regional pain syndrome. Psychiatry investigation. 2014;11(1):32–38. doi: 10.4306/pi.2014.11.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Marinus J, Moseley GL, Birklein F, Baron R, Maihöfner C, Kingery WS, Van Hilten JJ. Clinical features and pathophysiology of complex regional pain syndrome. Lancet Neurology. 2011;10(7):637–648. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70106-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].McCabe CS, Llewellyn A, Hibberd Y, White P, Davies L, Marinus J, Perez RSGM, Thomassen I, Brunner F, Sontheim C, Birklein F, et al. Complex Regional Pain syndrome: Patients’ priorities for defining recovery. British Journal of Pain. 2016;10(2 suppl):5–91. [Google Scholar]

- [39].McCabe C, Llewellyn A, Hibberd Y, White P, Davies L, Marinus J, Perez R, Thomassen I, Brunner F, Sontheim C, Birklein F, et al. Are you better? A multi-centre study exploring the patients’ definition of recovery from Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. 2016 doi: 10.1002/ejp.1138. Paper in preparation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Nicholas MK. The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: Taking pain into account. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(2):153–163. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].O’Connell NE, Wand BM, McAuley J, Marston L, Moseley GL. Interventions for treating pain and disability in adults with complex regional pain syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013:4. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009416.pub2. Art. No.: CD009416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Packham TL, Bean DJ, Johnson MH, Grieve S, McCabe CS, MacDermid J. Measurement properties of the SF-MPQ-2 in persons with CRPS: validity, scaling and Rasch analysis. doi: 10.1093/pm/pny202. Paper in preparation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Packham TL, Bean DJ, Johnson MH, Harden RN. Validity and responsiveness of the CRPS Severity Score. Paper in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Packham T, MacDermid JC, Henry J, Bain J. A systematic review of psychometric evaluations of outcome assessments for complex regional pain syndrome. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:1059–1069. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.626835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Pilkonis PA, Choi SW, Reise SP, Stover AM, Riley WT, Cella D, on behalf of the PROMIS Cooperative Group Item banks for measuring emotional distress from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®): depression, anxiety, and anger. Assessment. 2011;18(3):263–283. doi: 10.1177/1073191111411667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Riddle DL, Wade JB, Jiranek WA, Kong X. Preoperative pain catastrophizing predicts pain outcome after knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 2010;468(3):798–806. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0963-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Rodham K, McCabe C, Pilkington M, Regan L. Coping with chronic complex regional pain syndrome: advice from patients for patients. Chronic Illness. 2013;9(1):29–42. doi: 10.1177/1742395312450178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Schasfoort FC, Bussman JG, Stam HJ. Impairments and activity limitations in subjects with chronic upper limb complex regional pain syndrome type I. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(4):557–66. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Schwartzman RJ, Erwin KL, Alexander GM. The natural history of complex regional pain syndrome. Clin J Pain. 2009;25(4):273–280. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31818ecea5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Scott EL, Kroenke K, Wu J, Yu Z. Beneficial Effects of Improvement in Depression, Pain Catastrophizing, and Anxiety on Pain Outcomes: A 12-Month Longitudinal Analysis. J Pain. 2016;17(2):215–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Staniszewska S, Haywood K, Brett J, Tutton L. Patient and public involvement in patient-reported outcome measures: evolution not revolution. Patient. 2012;5(2):79–87. doi: 10.2165/11597150-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Sullivan ML. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale User Manual (English) Montreal, QC: McGill University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Sullivan ML, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7(4):524–532. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Sullivan M, Tanzer M, Stanish W, Fallaha M, Keefe FJ, Simmonds M, Dunbar M. Psychological determinants of problematic outcomes following Total Knee Arthroplasty. Pain. 2009;143:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Allen RR, Bellamy N, Brandenburg N, Carr DB, Cleeland C, Dionne R, Farrar JT, Galer BS, Hewitt DJ, et al. Core outcome domains for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2003;106:337–345. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry Analgesic Indications: Developing Drug and Biological Products. DRAFT guidance. 2014 http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM384691.pdf.

- [57].US Food and Drug Administration. Orphan drug designations and approvals. Neridronate. 2013 http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/opdlisting/oopd/OOPD_Results_2.cfm?Index_Number=372412.

- [58].Wertli M, Bachmann LM, Weiner SS, Brunner F. Prognostic factors in complex regional pain syndrome 1: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45(3):225–231. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wertli M, Kessels A, Perez R, Bachmann L, Brunner F. Rational pain management in complex regional pain syndrome 1 (CRPS 1)--a network meta-analysis. Pain Med. 2014;15(9):1575–1589. doi: 10.1111/pme.12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Wille N, Badia X, Bonsel G, Burström K, Cavrini G, Devlin N, Egmar AC, Greiner W, Gusi N, Herdman M, Jelsma J. Development of the EQ-5D-Y: a child-friendly version of the EQ-5D. Qual Life Res. 2010;19(6):875–86. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9648-y. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, Clarke M, Devane D, Gargon E, Tugwell P. Developing core outcome sets for clinical trials issues to consider. Trials. 2012;13:132. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.