Abstract

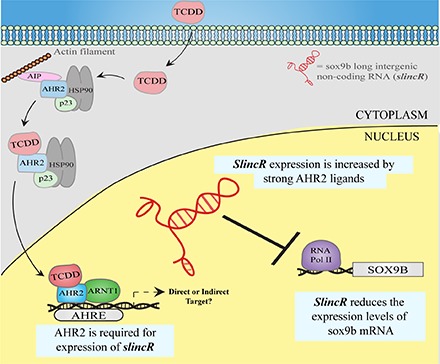

Xenobiotic activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) prevents the proper formation of craniofacial cartilage and the heart in developing zebrafish. Downstream molecular targets responsible for AHR-dependent adverse effects remain largely unknown; however, in zebrafish sox9b has been identified as one of the most-reduced transcripts in several target organs and is hypothesized to have a causal role in TCDD-induced toxicity. The reduction of sox9b expression in TCDD-exposed zebrafish embryos has been shown to contribute to heart and jaw malformation phenotypes. The mechanisms by which AHR2 (functional ortholog of mammalian AHR) activation leads to reduced sox9b expression levels and subsequent target organ toxicity are unknown. We have identified a novel long noncoding RNA (slincR) that is upregulated by strong AHR ligands and is located adjacent to the sox9b gene. We hypothesize that slincR is regulated by AHR2 and transcriptionally represses sox9b. The slincR transcript functions as an RNA macromolecule, and slincR expression is AHR2 dependent. Antisense knockdown of slincR results in an increase in sox9b expression during both normal development and AHR2 activation, which suggests relief in repression. During development, slincR was expressed in tissues with sox9 essential functions, including the jaw/snout region, otic vesicle, eye, and brain. Reducing the levels of slincR resulted in altered neurologic and/or locomotor behavioral responses. Our results place slincR as an intermediate between AHR2 activation and the reduction of sox9b mRNA in the AHR2 signaling pathway.

Introduction

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) model has proven to be an invaluable tool in multiple areas of research, such as development and toxicology (Dooley and Zon, 2000; Spitsbergen and Kent, 2003; Garcia et al., 2016). The anatomy and physiology of fish is homologous to humans (Ackermann and Paw, 2003); 84% of human disease-related genes are present in the zebrafish genome and about 70% of human genes have a zebrafish ortholog (Howe et al., 2013). The zebrafish has been used as a model to elucidate the molecular mechanisms responsible for 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) toxicity (Henry et al., 1997). In zebrafish, developmental exposure to TCDD causes impaired reproductive development, embryonic lethality, and/or severe developmental defects in several tissues, including heart, cartilage, and vasculature (reviewed in Carney et al., 2006).

TCDD toxicity is mediated through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) (reviewed in Beischlag et al., 2008). The AHR is a conserved receptor from invertebrates to vertebrates and is the only ligand-activated member of the basic helix-loop-helix PER-ARNT-SIM protein family (Hahn et al., 1997; Hao and Whitelaw, 2013). The AHR can be activated by many environmental contaminants, including chlorinated dioxins, biphenyls, and polyaromatic hydrocarbons (Knecht et al., 2013; Wall et al., 2015). Upon activation, AHR dimerizes with ARNT, translocates to the nucleus, and induces ligand-specific transcriptional changes (Beischlag et al., 2008; Goodale et al., 2015). In zebrafish, AHR2 and ARNT1 are the functional orthologs of mammalian AHR and ARNT, and loss of either protein protects against TCDD-induced toxicity phenotypes, including cardiac malformation, cartilage malformation, and reduced peripheral blood flow (Antkiewicz et al., 2006; Prasch et al., 2006).

Identification of the downstream molecular targets responsible for specific endpoints of AHR-dependent toxicity remain largely unknown; however, in zebrafish, sox9b has been identified as one of the most reduced transcripts in several AHR2 toxicity target organs (Andreasen et al., 2006, 2007; Xiong et al., 2008; Hofsteen et al., 2013). In zebrafish, an ancient genome duplication in the teleost lineage resulted in two Sox9 co-orthologs (sox9a and sox9b), which have undergone subfunction partitioning with both distinct and overlapping functions (Postlethwait et al., 2004; Yan et al., 2005). Sox9 is required for proper vertebrate embryonic development by specifying cell fate and differentiation in linages from all three germ layers (Akiyama et al., 2002, 2004; Haldin and LaBonne, 2010; Scott et al., 2010; Stolt and Wegner, 2010; Furuyama et al., 2011).

Sox9b is hypothesized to have a causal role in cartilage and heart TCDD-induced toxicity phenotypes in zebrafish. Antisense knockdown of sox9b was sufficient to produce the TCDD-like jaw phenotype, and TCDD-exposed zebrafish embryos injected with sox9b mRNA rescued the TCDD-induced jaw malformations (Xiong et al., 2008). TCDD exposure markedly reduces the expression of sox9b in zebrafish heart ventricles, and genetic ablation of sox9b results in TCDD-like heart malformations (Hofsteen et al., 2013). The Xiong et al. (2008) and Hofsteen et al. (2013) studies indicate that the reduction in sox9b expression is partially responsible for the TCDD-induced cartilage and heart malformation phenotypes. While eight putative AHR elements are located within 5 kb of the sox9b transcriptional start site, sox9b downregulation does not occur until 4 hours after AHR2 activation, suggesting sox9b is not a direct AHR2 target gene (Xiong et al., 2008). The mechanisms by which AHR2 activation leads to a reduction in sox9b expression and subsequent target organ toxicity are unknown.

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are defined as transcripts equal to or greater than 200 nucleotides that do not appear to encode a protein. Genetic and biochemical evidence suggests that a primary role for lncRNAs is the regulation of epigenetic processes, most likely by guiding chromatin-modifying enzymes to their target sites and by acting as a platform for chromosomal organization and protein complexes (Quinn and Chang, 2016). lncRNAs have been implicated in an array of biologic processes, including embryonic viability, development, response to stress, and cancer metastasis (Gutschner and Diederichs, 2012; Fatica and Bozzoni, 2014).

An important question left unanswered is how AHR2 activation by an exogenous ligand leads to the reduction of sox9b expression. We used the zebrafish model to probe the relationship between AHR2, a novel lncRNA (slincR), and sox9b. SlincR is located adjacent to the sox9b gene locus, and slincR expression was increased by a strong AHR ligand, which led us to test the hypothesis that slincR is regulated by AHR2 and is required for proper sox9b expression levels.

Materials and Methods

All gene-specific primers, in situ probes, and antibody information is listed in (Supplemental Table 1).

Fish Husbandry.

Tropical 5D (wild-type) and Tg(−2421/+29sox9b:EGFPuw2) sox9b reporter strains of zebrafish (Danio rerio) were reared according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols at the Sinnhuber Aquatic Research Laboratory, Oregon State University. Adult fish were raised in a recirculating water system (28°C ± 1°C) with a 14-hour:10-hour light-dark schedule. Spawning and embryo collection were conducted as described in Westerfield (2007).

Waterborne Exposure.

Shield-stage [∼6 hours post fertilization (hpf)] embryos were exposed to 1 ng/ml TCDD (311 nM, 95.3% purity; SUPELCO Solutions Within, Bellfonte, PA) or vehicle [0.1% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)] with gentle rocking for 1 hour in 20-ml glass vials (10 embryos/ml). Vials were also gently inverted every 15 minutes to ensure proper mixing. After the exposure, embryos were rinsed three times with fish water and then raised in 100-mm petri dishes. We developmentally exposed embryos to 10 µM benz(a)anthracene-7-12-dione (B[a]AQ) as previously described in Goodale et al. (2015).

5′ and 3′ Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends.

The FirstChoice RLM-RACE kit was performed as recommended by the manufacturer (Thermo Fisher; Eugene, OR). RNA was isolated at 48 hpf from whole embryos and cDNA was synthesized as described subsequently. Sanger sequencing was performed by the Core Facilities of the Center for Genome Research and Biocomputing at Oregon State University using an ABI 3730 capillary sequence machine (Thermofisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Embryo Homogenization and Subcellular Fractionation.

Approximately 50–60 embryos at 4 days post fertilization were homogenized with a 2-ml dounce homogenizer and tight pestle, and fractionated with a glucose gradient and centrifugation as detailed in Bogdanović et al. (2013). The homogenization solutions followed the recipes described in Simon (2013). For each cellular compartment, total RNA was isolated and cDNA was synthesized and quantified as described subsequently; however, only 2 ng of cDNA was used per reaction, the samples were not normalized to a reference gene, and whole embryo homogenate served as the calibrator. The samples analyzed consisted of three biologic replicates and two technical replicates, and U1 rRNA served as a positive control for nuclear enrichment.

Selective 2′-Hydroxyl Acylation Analyzed by Primer Extension (SHAPE).

Details of the experimental methods are summarized in Kladwang et al. (2011). Wild-type RNA reference ladders were created using 3′dideoxy-TTP in an equilmolar amount to dTTP during the reverse transcription reaction. The SHAPE data were analyzed using HiTRACE-WEB (Kim et al., 2013). Replicates from three independent samples were compared, and we performed a signal decay correction step to normalize for the typical exponential decay in fluorescent intensity as a function of elution time (Karabiber et al., 2013). We normalized each point by dividing by the average intensity of positions later in elution time (earlier in nucleotide position) rather than using the sum because in practice the sum overcorrected for the signal decay. We then averaged the replicates and computed the probability of an adduct by subtracting the scaled average DMSO from the average N-methylisatoic anhydride signal to remove background noise (Karabiber et al., 2013). We fit the data to a normal distribution and capped the data above the 90th percentile to control any signal that was likely due to saturation. Finally, we scaled the data to be between 0 and 2 (Vasa et al., 2008; Karabiber et al., 2013). The secondary structure was computed with the RNAfold WebServer (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAWebSuite/RNAfold.cgi), excluding isolated pairs, using dangling energies on both sides of the helices, and the Turner 2004 energy parameters (Turner and Mathews, 2010; Lorenz et al., 2011). Folding was performed at 24°C, in accordance with experimental conditions, and SHAPE reactivities were used in the calculation using the Deigan algorithm with default parameters (Deigan et al., 2009).

Morpholino Injection.

Approximately 2 nl total volume of a 1 mM solution of each morpholino (MO) were microinjected into the yolk of wild-type 5D and sox9b-eGFP reporter embryos at the one-cell stage. To test the effect of knocking down slincR expression levels, a splice blocking MO targeting the exon/intron boundary of slincR exon 1 (slincR-MO: 5′ GAC CTA AAC TCG ACC TTA CCA GAT C 3′) and a standard negative control (ConMO: 5′ CCT CTT ACC TCA GTT ACA ATT TAT A 3′) were obtained from GeneTools (Philomath, OR). Two methods were used to validate knockdown efficiencies: 1) total RNA was isolated and cDNA was synthesized and quantified, and/or 2) in situ hybridization was performed using a slincR probe (both detailed subsequently).

RNA Extraction and mRNA Quantification.

Total RNA was extracted from 48 hpf whole embryos using RNAzol (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, OH) and a bullet blender with 0.5 mM zirconium oxide beads (Next Advance, Averill Park, NY) as recommended by the manufacturer. RNA quality and quantity were assessed using a SynergyMix microplate reader with a Gen5 Take3 module (BioTek, Winooski, VT). Each biologic sample consisted of 20 embryos with a minimum of three biologic replicates per condition. Total RNA (1 µg) was reverse transcribed into cDNA with random primers using the ABI High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The 20 µl reactions consisted of 10 µl 2X SYBR Green Master Mix (Roche, Pleasanton, CA), 0.4 µl each of 10 µM forward and reverse primers, and 20 ng cDNA. The expression values were normalized to β-actin and analyzed with the 2−ΔΔCT method as described in Livak and Schmittgen (2001). The results were statistically analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 7.02 software program (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA). The data were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk normality test and analyzed with two-way analysis of variance, and a correction for multiple comparisons was performed using the Dunnett’s test (95% confidence intervals) or a paired t test and corrected for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Sidak method, with α = 0.05. Error bars indicate S.D. of the mean. We used the following calculation to determine the MO knockdown efficiencies: % knockdown = (1 − ΔΔCT) × 100%. All experiments were independently repeated a minimum of two times.

In Situ Hybridization and Immunohistochemistry.

In situ localization of RNA was performed on whole embryos (n = 6–10 embryos) at the respective time points as described previously (Thisse and Thisse, 2008), with the exception that the embryos were permeabilized in 2% hydrogen peroxide in 100% methanol for 20 minutes prior to the initial embryo rehydration. Additionally, probes were hybridized in a final concentration of 10% dextran sulfate. The sox9b probe was obtained from Chiang et al. (2001). The slincR, notch3, and adamts3 probes were prepared by PCR amplification from a cDNA template as described in (Thisse and Thisse, 2008). Dual in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry samples were performed on the Tg(−2421/+29sox9b:EGFPuw2) sox9b reporter line. Embryos were imaged in 3% methylcellulose at room temperature using a Keyence BZ-x700 at 10X with 0.45 aperture and processed with the BZ-x Analyzer software (Keyence, Osaka, Japan).

Larval Morphology and Behavior Screen.

Zebrafish embryos were injected at the 1-cell stage with MOs as described previously and placed into 96-well plates after hatching (∼48–60 hpf), with 24 embryos per injection group. The larval photomotor response assay consisted of 3-minute light and dark alternating periods, for a total of four light-dark transitions, with the first transition representing an acclimation period. The Viewpoint Zebrabox systems (Viewpoint Behavior Technology, Montreal, Canada) were used to analyze photography induced larval locomotor activity in 120 hpf larvae. We followed the protocols and analyzed the overall area under the curve for the last three light-dark cycles compared with control morphants using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (P < 0.01) as described in Knecht et al. (2017). We used 1% alpha to control for type I error inflation rather than controlling the family-wise error rate since we were not correcting for multiple treatments but only for a control and treatment group. Zebrafish were evaluated at 120 hpf for mortality and a suite of 17 physical malformations prior to the viewpoint assay, and embryos identified to be malformed were excluded from the viewpoint data analysis (Truong et al., 2011). The morphology data were analyzed using a Fisher’s exact test because of its utility of low category counts and because it does not make distributional assumptions (as the χ2 test does). A Bonferroni multiple comparisons test with control for family-wise error rate was used. The experiment was performed two independent times.

Results

Molecular Characterization of SlincR.

We previously performed an RNA-sequencing experiment on 48 hpf whole embryos treated with a strong AHR2 ligand (10 µM B[a]AQ) to identify the transcriptional networks of protein coding genes that are regulated by AHR2 (Goodale et al., 2015). Recent advances in our ability to measure RNA transcripts have unveiled lncRNAs as important regulators of gene expression (Quinn and Chang, 2016). We mined the data from the Goodale et al. (2015) study in an effort to discover potential lncRNAs that are regulated by AHR2. Using Ensembl’s zebrafish genome build Zv9 (release 79) (http://www.ensembl.org/index.html), we identified a novel transcript that displayed a log 2-fold increase of 3.2 upon developmental exposure to 10 µM B[a]AQ. A portion of the novel transcript matched the Ensembl annotated lncRNA si:Ch1073-384e4.1, which is located adjacent to the sox9b gene on the opposite strand of chromosome 3. The large increase in expression in response to a strong AHR2 ligand and the close proximity to the sox9b locus led us to hypothesize that si:Ch1073-384e4.1 may be regulated by AHR2 and transcriptionally represses sox9b. Using 5′ and 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends and sequencing analysis, the transcript we identified partially overlaps with the Ensembl annotated lncRNA, si:Ch1073-384e4.1. This novel transcript, sox9b long intergenic noncoding RNA (slincR, Genbank accession number KY085961), shares a 57.6% identity with si:Ch1073-384e4.1, with a majority of the similarities found in exon 1 of both transcripts (data not shown). SlincR is 466 base pairs in length, contains three exons, and is polyadenylated (Fig. 1A). We were unable to consistently amplify the Ensembl si:Ch1073-384e4.1 transcript in whole embryos treated with DMSO or B[a]AQ (data not shown). We note that si:Ch1073-384e4.1 and slincR represent alternative splice variants; however, slincR appears to be the most abundant transcript in our fish population. The core AHR element (5′-T/GCGTG-3′) is present in multiple locations in the slincR promoter, suggesting slincR may be a direct AHR target gene (Fig. 1A). When comparing the zebrafish slincR-sox9b loci to that of the mouse and human genomes, the spatial arrangement and orientation of potential slincR orthologs relative to Sox9 and the presence of AHR elements in the promoters of the potential orthologs are conserved. Thus, we expect the lncRNA-Sox9 target relationship to be similar between fish and mammals.

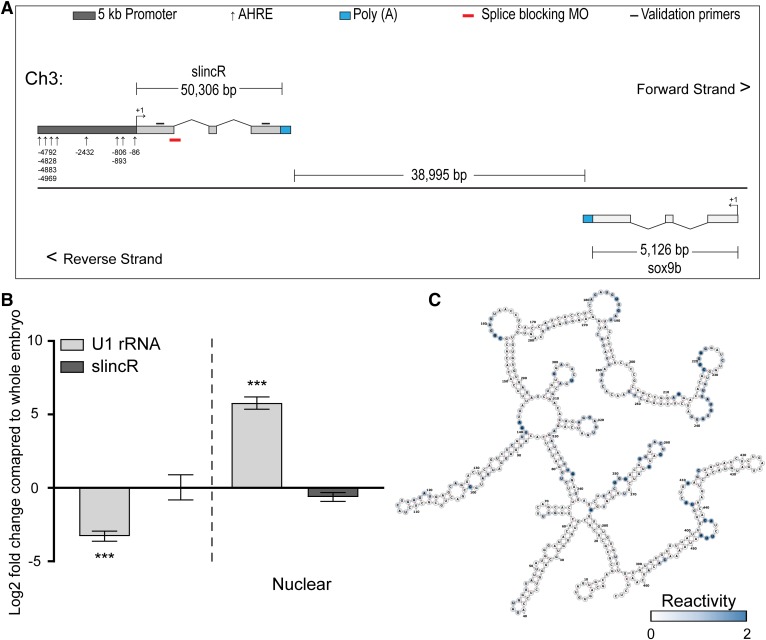

Fig. 1.

The slincR and sox9b locus on chromosome 3, subcellular enrichment, and SHAPE-enhanced prediction of slincR secondary structure. (A) Schematic diagram of the slincR and sox9b locus on chromosome 3 (not to scale). The Ensembl splice variant si:Ch1073-384e4.1 is not depicted for clarity. (B) Subcellular enrichment of slincR in 96 hpf whole embryos. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on whole embryo, cytoplasmic, and nuclear homogenate samples. U1 rRNA served as a positive control for nuclear enrichment. Expression values were analyzed with the 2−ΔΔCT method; however, we did not normalize to a reference gene. Results for (B) were statistically analyzed using a paired t test and corrected for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Sidak method, with α = 0.05. Error bars indicate S.D. of the mean. ***P < 0.001 compared with whole embryo. (C) SlincR’s predicted secondary structure. Selective 2′-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension (SHAPE) was run in triplicate from three independent samples. We normalized the data to be between 0 and 2 and entered the SHAPE reactivities into RNAfold. Unreactive nucleotides (white) participate in canonical base pairs, whereas nucleotides in loops, bulges, and other connecting regions are reactive (blue).

To determine the cellular compartment(s) in which slincR is localized, we homogenized ∼50–60 whole embryos at 96 hpf, and then used standard centrifugation fractionation methods, followed by quantitative real-time PCR. There was no significant difference in the relative amounts of slincR located in the nucleus versus the cytoplasm (Fig. 1B). Previous reports have demonstrated that quantitative, nucleotide resolution information from a selective 2′-hydroxyl acylation, analyzed by primer extension (SHAPE) experiments, can result in RNA secondary structure predictions with accuracies up to 96%–100% (Deigan et al., 2009). Briefly, SHAPE allows the probing of RNA secondary structures at single-nucleotide resolution by incubating RNA with N-methylisatoic anhydride, which selectively modifies flexible nucleotides and inhibits reverse transcription. The RNA is reverse transcribed, and modified bases are detected via capillary electrophoresis; thus, the SHAPE reactivity data can discriminate between base-paired versus unconstrained or flexible nucleotides in a RNA molecule. We used SHAPE-generated pseudo-free energies, in conjunction with RNAfold, to increase the accuracy of slincR’s predicted secondary structure (Fig. 1C). We scaled the data to be between 0 and 2 and entered the SHAPE reactivities into RNAfold. Unreactive nucleotides (white) participate in canonical base pairs, whereas nucleotides in loops, bulges, and other connecting regions are reactive (blue). The tertiary structure is an additional level of information that is required to understand the slincR structure-function relationship.

SlincR and Sox9b Are Expressed in Adjacent and Overlapping Tissues through Multiple Stages of Development.

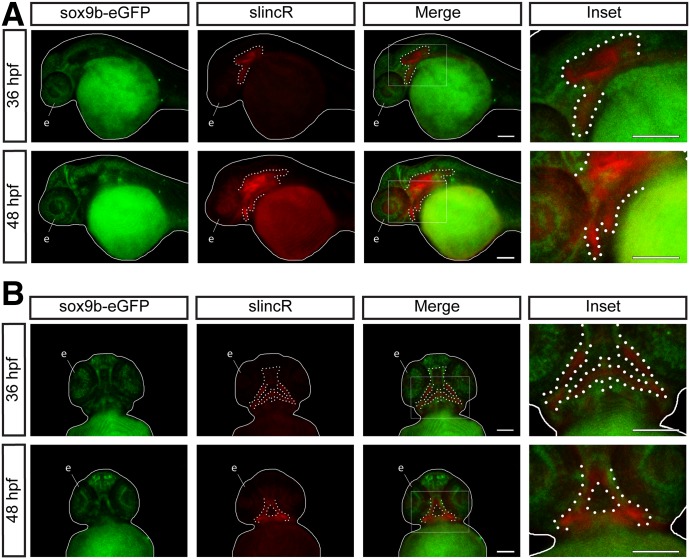

To better understand endogenous functions of slincR, we investigated expression relative to sox9b with in situ hybridization in embryos of the wild-type and sox9b-eGFP reporter lines over multiple developmental time points (24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 hpf). SlincR expression was not detectable at 24 hpf, but starting at 36 hpf expression was evident in the otic vesicle, eye, and jaw/snout region (Table 1). Sox9b-eGFP and slincR were expressed in adjacent and overlapping tissues, including the eye, otic vesicle, and lower jaw region during multiple stages of development (Fig. 2, A and B).

TABLE 1.

SlincR expression at multiple developmental stages

For each organ or structure 6–10 embryos were scored at each time point.

|

slincR Expression |

Developmental Stage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 |

36 |

48 |

60 |

72 |

|

| hpf | hpf | hpf | hpf | hpf | |

| Heart | N | N | N | N | N |

| Brain | N | N | N | N | N |

| Otic vesicle | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Eye | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Jaw/snout | N | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Pectoral bud/fin | N | N | N | N | N |

| Notochord | N | N | N | N | N |

N, No; Y, Yes.

Fig. 2.

SlincR and sox9b-eGFP are expressed in adjacent and overlapping tissues through multiple stages of development. Lateral (A) and ventral (B) views of dual immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization samples targeting sox9b-eGFP (green) and slincR (red) in sox9b-eGFP reporter fish at 36 and 48 hpf (n = 6–10 embryos). The fish are outlined with a white line, slincR expression is outlined with a dotted white line, and the eye is labeled the letter e. The white rectangle represents the magnified area depicted in the inset. Both scale bars represent 100 µm. All experiments were independently repeated a minimum of two times.

SlincR Expression Is AHR2 Dependent.

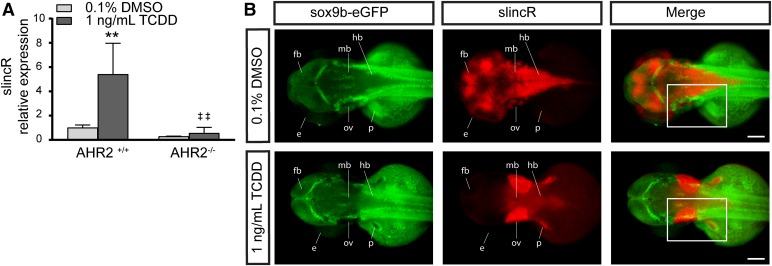

To test our hypothesis that activation of AHR2 results in an increase in slincR expression, we used the previously characterized AHR2-null zebrafish line (Goodale et al., 2012). In 48 hpf wild-type samples, slincR expression was significantly increased upon exposure to TCDD (Fig. 3A). However, in AHR2-null animals slincR expression was significantly lower compared with wild type at 48 hpf, and no increase in slincR expression was observed after developmental exposure to TCDD (Fig. 3A). These results demonstrate that slincR expression is increased by exposure to strong AHR ligands (B[a]AQ and TCDD) and that this induction is an AHR2-dependent event.

Fig. 3.

Comparative analysis of AHR2 functional status and slincR expression levels and spatial pattern relative to sox9b. (A) SlincR expression in 48 hpf wild-type 5D (AHR2+/+) and AHR2-null (AHR2−/−) whole embryos developmentally exposed to 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control) or 1 ng/ml TCDD (n = 3 biologic replications). Results were statistically analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 7.02 software. The data were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk normality test, analyzed with two-way analysis of variance, and correction for multiple comparisons was performed using the Dunnett’s test (95% confidence intervals). Error bars indicate S.D. of the mean. **P < 0.01 compared with DMSO control. ##P < 0.01 compared with TCDD control. (B) Dorsal view of dual immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization samples targeting sox9b-eGFP (green) and slincR (red) in 48 hpf embryos (n = 6–10 embryos). The Tg(−2421/+29sox9b:EGFPuw2) sox9b reporter line embryos were developmentally exposed to 0.1% DMSO or 1 ng/ml TCDD. In the TCDD-exposed samples, the regions with increased slincR expression had a corresponding decrease in sox9b-eGFP expression (white rectangle); e = eye, ov = otic vesicle, p = pectoral fin, fb = forebrain, mb = midbrain, and hb = hindbrain; 100 µm scale bar. All experiments were independently repeated a minimum of two times.

To elucidate the changes in the spatial expression pattern of slincR relative to sox9b upon AHR2 activation, we exposed the previously characterized sox9b-eGFP reporter line Tg(−2421/+29sox9b:EGFPuw2) to 0.1% DMSO or 1 ng/ml TCDD, and performed dual immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization (Plavicki et al., 2014). Exposure to TCDD displayed decreased slincR expression in the brain and increased expression surrounding the otic vesicle, relative to vehicle-exposed samples (Fig. 3B). In the TCDD-exposed samples, the regions with increased slincR expression had a corresponding decrease in sox9b-eGFP expression (Fig. 3B, white rectangle). The slincR expression pattern was similar in all fish examined within each treatment group (Supplemental Fig. 1). Of note, exposure to TCDD also resulted in slincR expression in the pectoral fin, which was not seen in DMSO-treated samples (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, the 0.1% DMSO-exposed embryos (vehicle control) displayed increased slincR expression in the brain compared with TCDD-exposed embryos. The nonexposed embryos (DMSO or TCDD) did not show any expression of slincR in the brain (Fig. 3; Table 1). The specific and overlapping expression patterns suggest, but do not prove, interaction between sox9b and slincR.

SlincR Is Required for Proper Expression Levels and Spatial Pattern of Sox9b during Development.

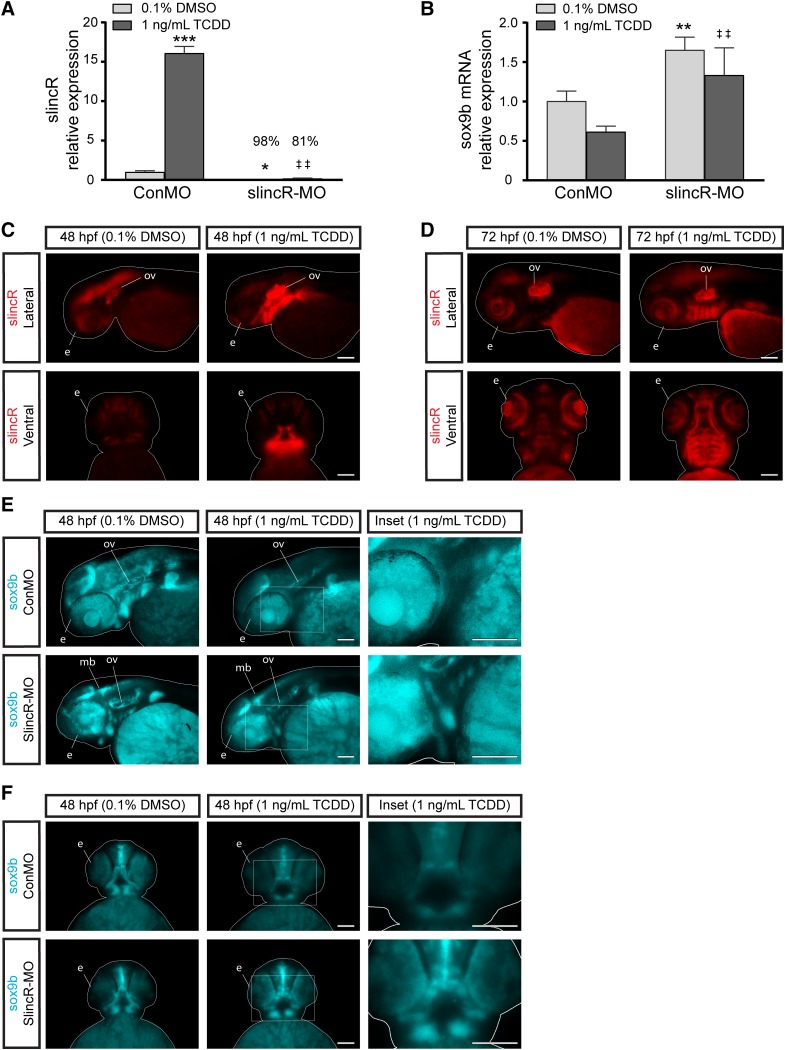

To probe the slincR-sox9b relationship during development antisense knockdown of the endogenous slincR and splice variant si:Ch1073-384e4.1 levels via a splice blocking MO was performed (Fig. 4A). We tested knockdown efficiencies in 48 hpf slincR morphants exposed to DMSO or TCDD, which displayed 98% and 81% knockdown efficiencies, respectively (Fig. 4A). In situ hybridization of slincR from 48 and 72 hpf (Fig. 4, C and D) control morphant samples exposed to TCDD shows that slincR expression is increased in the otic vesicle and the lower jaw/snout region. In situ hybridization also confirmed that slincR was barely detected in slincR morphants at 48 hpf when treated with DMSO; however, expression of slincR was visible in the otic vesicle and lower jaw region in the TCDD-treated samples (Supplemental Fig. 2). Knockdown of slincR during early development was not sufficient to rescue the TCDD-induced cartilage malformation phenotype. As previously mentioned, activation of AHR2 by TCDD exposure results in a reduction in the expression of sox9b mRNA in craniofacial cartilage, regenerating caudal fin, and heart tissues (Andreasen et al., 2006, 2007; Xiong et al., 2008; Hofsteen et al., 2013); therefore, we hypothesized that upon exposure to a strong AHR2 ligand, slincR increases and is required for the TCDD-mediated reduction in sox9b expression. To determine if slincR expression was required for the reduction of sox9b mRNA in TCDD-treated embryos, we exposed control and slincR morphants to 0.1% DMSO or 1 ng/ml TCDD, isolated RNA from whole embryos at 48 hpf, and then measured the relative expression levels of sox9b mRNA. In control morphants, exposure to TCDD resulted in a decrease in sox9b mRNA levels (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the slincR morphants exposed to either DMSO or TCDD displayed a significant increase in sox9b expression compared with the control morphants (Fig. 4B). Next, we used in situ hybridization to label sox9b mRNA in 48 hpf slincR and control morphants exposed 0.1% DMSO or 1 ng/ml TCDD. SlincR morphants exposed to DMSO displayed an increase in sox9b expression in the otic vesicle and midbrain region compared with DMSO-exposed controls (Fig. 4E). In response to TCDD exposure, slincR morphants also displayed an increase in sox9b expression in the otic vesicle, lower jaw/snout region, and eye compared with control morphants (Fig. 4, E and F). The data suggest that slincR is required for normal sox9b expression levels and for the TCDD-mediated reduction in sox9b expression.

Fig. 4.

Comparative analysis of the relative expression of slincR and sox9 in TCDD-exposed samples. SlincR (A) and sox9b mRNA (B) quantitative expression in 48 hpf whole embryo slincR (slincR-MO) and control (ConMO) morphants developmentally exposed to 0.1% DMSO (vehicle control) or 1 ng/ml TCDD. For all quantitative PCR data, expression values were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method. Expression values were normalized to β-actin and the control morphants served as the calibrator. Samples represent a minimum of three biologic replicates. Results were statistically analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 7.02 software. The data were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk normality test and analyzed with two-way analysis of variance and correction for multiple comparisons was performed using the Dunnett’s test (95% confidence intervals). Error bars indicate S.D. of the mean; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with controls; ##P < 0.01 compared with TCDD control. (C–F) dorsal and lateral views of in situ hybridization samples targeting slincR (red) and sox9b (blue) in 48 hpf (C, E, and F) and 72 hpf (D) embryos (n = 6–10 embryos). (C and D) Representative images from control morphants. In the TCDD-exposed samples, slincR morphants displayed increased sox9b expression patterns compared with controls (white rectangle, which represents the magnified image in the inset). The fish are outlined with a white line; e = eye, ov = otic vesicle, p = pectoral fin, and mb = midbrain; 100 µm scale bar. All experiments were independently repeated a minimum of two times.

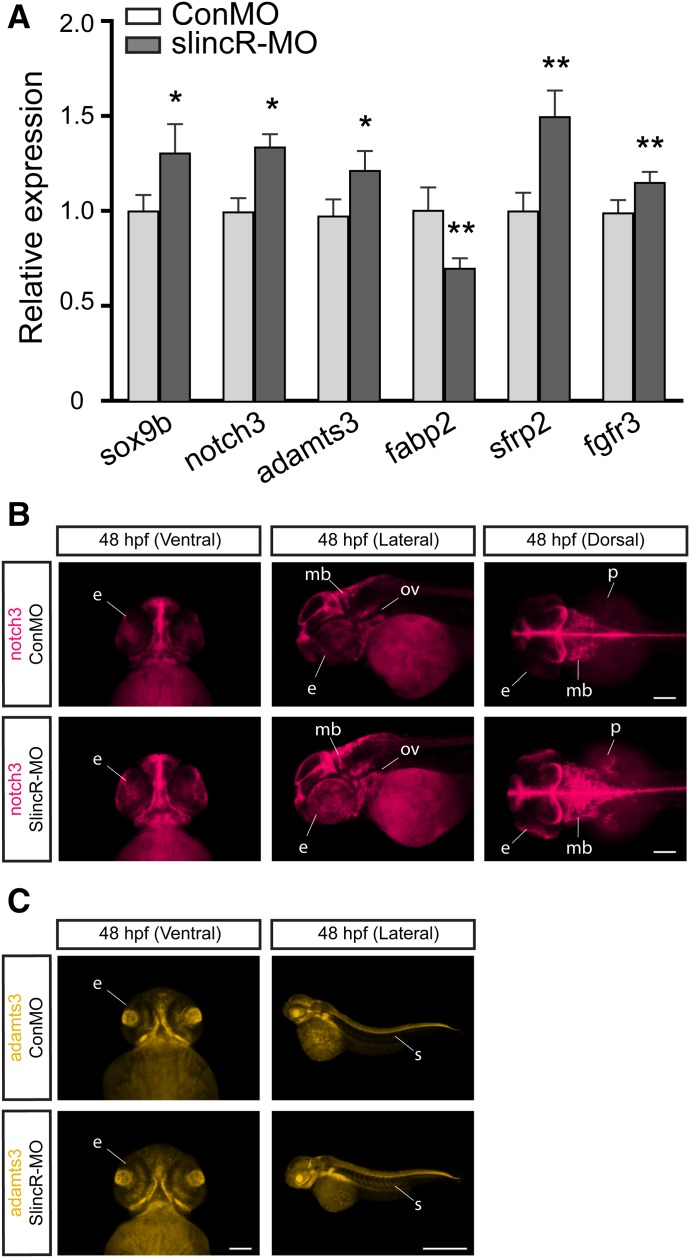

Knocking down slincR expression altered sox9b mRNA transcript levels (Fig. 4B) and spatial expression patterns (Fig. 4, E and F). Next, we determined if the increased expression of sox9b observed in the slincR morphants had a significant effect on known sox9b downstream target genes. We selected genes that were experimentally identified as direct Sox9 target genes in mammalian primary chondrocytes via a chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing experiment and examined the orthologous genes in our zebrafish model (Ohba et al., 2015). In the slincR morphants, five out of the nine genes selected had significantly altered relative expression levels at 48 hpf compared with the control (Fig. 5A). The transcripts for notch3, adamts3, sfrp2, and fgfr3 all had an increase in expression in slincR morphants, while fabp2 displayed a decrease in expression compared with controls. To identify the tissues/regions with altered expression patterns, we used in situ hybridization to label notch3 and adamts3 (a protease that cleaves notch) mRNA in 48 hpf slincR and control morphants (Fig. 5, B and C). Similar to the slincR and sox9b expression patterns, notch3 and adamts3 are also expressed in the lower jaw/snout region, eye, otic vesicle, and brain at 48 hpf. SlincR morphants clearly displayed an increase in notch3 expression in the midbrain, hindbrain, eye, and pectoral fin and increased adamts3 expression in the somites of the trunk. These results suggest slincR knockdown had a modest but significant impact on the sox9b transcriptional regulatory network across multiple tissues during development.

Fig. 5.

Comparative analysis of the relative expression of sox9b and downstream targets in slincR morphants. (A) Quantitative expression levels of sox9b and downstream targets in slincR and control morphants at 48 hpf. Five out of the nine downstream target genes were significantly different when compared with control morphants. Expression values were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method, normalized to β-actin, and the control morphants served as the calibrator. Samples represent a minimum of three biologic replicates. Results were statistically analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 7.02 software. The data were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk normality test, analyzed using a paired t test, and corrected for multiple comparisons using the Holm-Sidak method, with α = 0.05. Error bars indicate S.D. of the mean; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with controls. Dorsal, ventral, and lateral views of in situ hybridization samples targeting notch3 (B) and adamts3 (C) in 48 hpf slincR and control morphants (n = 6–10 embryos); e = eye, ov = otic vesicle, p = pectoral fin, s = somite, and mb = midbrain; 100 µm scale bar.

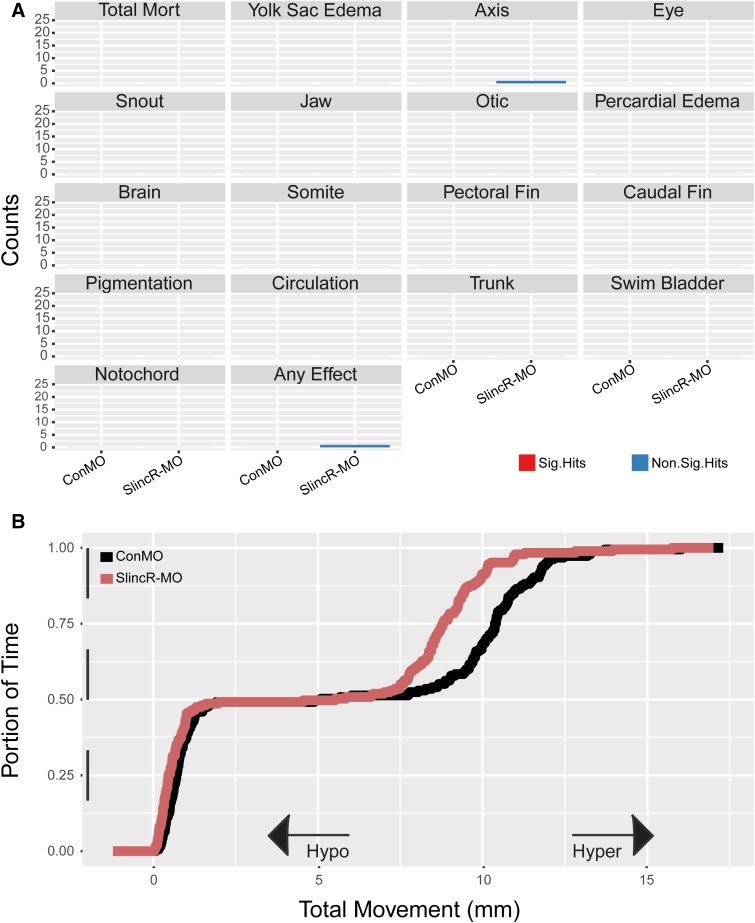

SlincR Expression Is Required for Normal Neurologic and/or Locomotor Behavioral Responses to Light.

We used an 18 endpoint viability and malformation screen on 120 hpf fish (n = 24) to determine the morphologic impact of knocking down slincR expression levels early in development. Reduced slincR expression levels during development did not result in any statistically significant malformation incidences at 120 hpf (Fig. 6A). Morphologically, the slincR morphants were indistinguishable from control morphants, with both appearing developmentally normal. To evaluate the effect of reduced slincR expression levels on neurologic and locomotor behavior, 120 hpf fish (n = 23) were subjected to a light-dark photometer assay that reported hyperactive or hypoactive swimming (Knecht et al., 2017). The morphologic and behavioral assays were conducted on the same 120 hpf fish. Reducing slincR expression during early development resulted in a modest but significantly hypoactive photomotor response (P < 0.01; −14.04% difference in mean area under the curve compared with controls) (Fig. 6B). The larval photomotor response assay suggested that reduced slincR expression significantly affected some aspect(s) of neuromuscular and/or sensory system development.

Fig. 6.

Phenotypic analysis of reduction in slincR expression during early development. (A) An 18-endpoint morphologic screen in slincR and control morphants at 120 hpf (n = 24). No significant malformations were observed in the slincR morphants. Control and slincR morphant evaluations were completed in a binary notation (present/absent) and statistically compared using Fisher’s exact test at P < 0.05 for each endpoint. (B) Larval photomotor response (LPR) in control and slincR morphants at 120 hpf (n = 23) using the Viewpoint Zebrabox systems. SlincR morphants displayed a hypoactive response (P < 0.01), with −14.04% difference of the mean area under the curve when compared with controls. The LPR assay consisted of 3 minutes of light and dark alternating periods, for a total of four light-dark transitions, with the first transition representing an acclimation period. The black and white bar along the y-axis indicates the 3 minutes of light (white) and dark (black) alternating periods. Larval zebrafish at this developmental stage display increased locomotion during periods of darkness. The overall area under the curve was analyzed for the last three light-dark cycles compared with control morphants using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (P < 0.01). All experiments were independently repeated a minimum of two times.

Discussion

The AHR is a key mediator of cell signaling during development and homeostasis, as well as in response to environmental pollutant exposure (Hao and Whitelaw, 2013). Dysregulation of AHR has been associated with multiple diseases, such as coronary artery and prostrate disease (Vezina et al., 2009; Schneider et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2015). In humans, haploinsufficiency of SOX9 is associated with organ malformations, while SOX9 duplication results in male-to-female sex reversal (Huang et al., 1999). Increased or ectopic expression of SOX9 is associated with liver fibrosis and several different cancer types (Pritchett et al., 2011; Matheu et al., 2012). Sox9 plays an important role during embryonic development, determining cell fate in cells derived from all three germ layers (Jo et al., 2014). Recent work has also suggested a role for Sox9 in cell maintenance and specification during adulthood (Furuyama et al., 2011; Barrionuevo et al., 2016). Our study examined the relationship between AHR2, a novel lncRNA (slincR), and sox9b using the zebrafish model, to gain insight into how inappropriate AHR2 activation leads to a reduction in sox9b expression and impairs cartilage and heart development. Understanding the layers of regulation downstream from AHR will aid in our understanding of the role of AHR in development and how xenobiotic activation or misexpression of AHR leads to negative phenotypic consequences.

The results of this study suggest that slincR expression is AHR2 dependent and is required for proper sox9b expression levels during normal development. Sox9b is hypothesized to have a causal role in the AHR2 toxicity signaling pathway since antisense knockdown of sox9b was sufficient to phenocopy TCDD-induced craniofacial cartilage malformations (Xiong et al., 2008). Additionally, a sox9b mutant partially phenocopied AHR2-activated cardiac malformations in zebrafish, indicating sox9b and other unidentified genes are responsible for the heart malformation phenotype (Hofsteen et al., 2013). In the absence of functional AHR2, slincR expression was significantly lower than in wild-type fish and did not increase in response to TCDD exposure. Additionally, when we knocked down the levels of slincR and activated the AHR2 pathway, we did not see a reduction in sox9b expression. These results place slincR as an intermediate between AHR2 activation and the reduction of sox9b expression in the AHR signaling pathway.

In support of a relationship between slincR and sox9b, slincR was shown to be expressed in adjacent and overlapping tissues and to have a significant impact on the expression of sox9b and several of its downstream targets. Our data demonstrate that the slincR transcript functions as an RNA macromolecule and acts locally (in cis) on chromosome 3 to regulate the spatial and relative expression levels of sox9b. We detected slincR expression in tissues that have reported essential functions for sox9, including the otic vesicle, eye, and brain (Yan et al., 2005; Scott et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2013). Upon TCDD exposure, sox9b expression is reduced in zebrafish heart ventricles (Hofsteen et al., 2013). We did not detect slincR in the developing heart, which suggests there are tissue-specific mechanisms of sox9b regulation. In slincR morphants, we detected significant differences in the relative expression levels of sox9b and known Sox9 targets that were previously identified in mammalian primary chondrocytes. Several of the significantly altered genes are also known to converge with Sox9 signaling in multiple organs through development, including fgf3, sfrp2 (Wnt ligand), and notch3 (Jo et al., 2014). In slincR morphants, notch3 and adamts3 (protease that cleaves notch receptors) both had a small but significant increase in their relative expression and displayed altered spatial expression patterns. In cartilage development, notch signaling has been shown to regulate the onset of chondrocyte maturation in a Sox9-dependent manner and to negatively regulate chondrocyte differentiation by suppressing Sox9 transcription (Kohn et al., 2015). Evidence from mouse chondrogenic ATDC5 cells suggests that notch signaling initially induces Sox9 expression, but prolonged notch signaling leads to suppression of Sox9 transcription via secondary effectors (Chen et al., 2013). Notch signaling in ectoderm-derived cells, which includes the central nervous system, otic placode, and eye, was shown to induce sox9 expression for stem cell maintenance, astrogliogenesis, and eye development (Martini et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2013).

In our study, reducing the expression of slincR during early stages of development did not result in overt malformations at the organismal level. These results are not surprising for a number of reasons. In zebrafish, a phenotypic analysis of 1,216 non-sense and essential splice mutations resulted in 87.58% of mutations linked to no observable morphologic or behavioral phenotype. This implies that the zebrafish genome operates under a high degree of redundancy and may indicate the presence of genetic compensatory networks (Kettleborough et al., 2013). Additionally, we hypothesize that slincR expression is downstream from AHR2, and the AHR2-null line does not display overt malformations during embryonic development (Goodale et al., 2012).

A reduction in slincR expression during early stages of embryonic development resulted in altered photomotor responses. We also detected slincR expression in the brain of DMSO- and TCDD-exposed embryos. DMSO is known to cause membrane destabilization and has been used to facilitate administration of drugs that do not normally cross the blood brain barrier (Pardridge, 2005; Kleindienst et al., 2006). SlincR expression in the brain was not seen in DMSO-exposed AHR2-null mutants. It is plausible that exposure to DMSO decreased the integrity of the blood brain barrier, allowing an unidentified ligand to activate the AHR2 receptor in the brain. SlincR morphants also displayed altered sox9b and notch3 expression patterns in the brain. Mammalian and zebrafish models have identified a large number of lncRNAs that exhibit neuronal-specific expression, which suggests a role for lncRNAs in the establishment and maintenance of the vertebrate nervous system (Mercer et al., 2008; Kaushik et al., 2013). In the adult zebrafish, the largest number of tissue-specific lncRNA transcripts was expressed in the brain (Kaushik et al., 2013). In mammals and zebrafish, Sox9 is expressed in the brain and is a conserved transcription factor involved in central nervous system development (Esain et al., 2010; Scott et al., 2010; Martini et al., 2013; Plavicki et al., 2014).

Our study did not address how slincR expression leads to reduced sox9b mRNA levels. Future studies will be conducted to establish the mechanism of slincR-induced sox9b suppression. A limitation of this study was our inability to maintain slincR repression during later stages of development to determine late-stage phenotypic consequences. This prevented us from determining slincR’s contribution to TCDD-induced toxicity phenotypes, such as cartilage malformation. Knocking down slincR during early development is not sufficient to rescue the TCDD-induced cartilage malformation phenotype. In future studies, we will use a CRISPR/Cas9-generated slincR knockout line and increase the resolution by examining the tissues and cells in which slincR is expressed.

In summary, we identified an AHR2-dependent novel lncRNA (slincR) that is required for proper sox9b expression during normal development and in response to a strong AHR ligand. SlincR acts in cis to regulate sox9b expression; however, additional experiments are required to determine the mechanism of slincR-induced reduction of sox9b. In concordance with other lncRNA studies, slincR expression was tissue specific and was not required for normal morphologic development (measured at the organismal level). SlincR was required for normal photomotor behavior in the larval stage, suggesting a role for slincR in neuromuscular and/or sensory system development. This study adds to the growing body of research demonstrating important roles of lncRNAs during neural development, and adds to our understanding of how AHR signaling intersects with the sox9b network to mediate developmental effects of environmental pollutants.

Acknowledgments

The slincR transcript sequence has been deposited into Genbank (accession number KY085961). The authors thank Dr. Michael Simonich and Cheryl Dunham for help with editing the manuscript; the agents of Sinnhuber Aquatic Research Laboratory (SARL), especially Carrie Barton and Greg Gonnerman, for help regarding fish husbandry and phenotypic screening; also Dr. Lisa Truong for assistance with data analysis. The Sox9b reporter line Tg(−2421/+29sox9b:EGFPuw2) was generously provided by the Richard E. Peterson Laboratory from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI.

Abbreviations

- AHR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- B[a]AQ

benz(a)anthracene-7-12-dione

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- hpf

hours post fertilization

- lncRNA

long noncoding RNA

- MO

morpholino

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- SHAPE

selective 2′-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension

- TCDD

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Tanguay, Hendrix, Garcia, Goodale.

Conducted experiments: Goodale, Garcia, La Du.

Performed data analysis: Hendrix, Wiley, Garcia, Goodale.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Goodale, Garcia, La Du, Tanguay.

Footnotes

This research was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grants P42 ES016465, R21 ES025421, T32 ES07060, F31 ES026518, F32 ES025082, and P30 ES000210].

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Ackermann GE, Paw BH. (2003) Zebrafish: a genetic model for vertebrate organogenesis and human disorders. Front Biosci 8:d1227–d1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H, Chaboissier MC, Behringer RR, Rowitch DH, Schedl A, Epstein JA, de Crombrugghe B. (2004) Essential role of Sox9 in the pathway that controls formation of cardiac valves and septa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:6502–6507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama H, Chaboissier MC, Martin JF, Schedl A, de Crombrugghe B. (2002) The transcription factor Sox9 has essential roles in successive steps of the chondrocyte differentiation pathway and is required for expression of Sox5 and Sox6. Genes Dev 16:2813–2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen EA, Mathew LK, Löhr CV, Hasson R, Tanguay RL. (2007) Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation impairs extracellular matrix remodeling during zebra fish fin regeneration. Toxicol Sci 95:215–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen EA, Mathew LK, Tanguay RL. (2006) Regenerative growth is impacted by TCDD: gene expression analysis reveals extracellular matrix modulation. Toxicol Sci 92:254–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antkiewicz DS, Peterson RE, Heideman W. (2006) Blocking expression of AHR2 and ARNT1 in zebrafish larvae protects against cardiac toxicity of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Toxicol Sci 94:175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrionuevo FJ, Hurtado A, Kim GJ, Real FM, Bakkali M, Kopp JL, Sander M, Scherer G, Burgos M, Jiménez R. (2016) Sox9 and Sox8 protect the adult testis from male-to-female genetic reprogramming and complete degeneration. eLife 5:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beischlag TV, Luis Morales J, Hollingshead BD, Perdew GH. (2008) The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex and the control of gene expression. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr 18:207–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanović O, Fernández-Miñán A, Tena JJ, de la Calle-Mustienes E, Gómez-Skarmeta JL. (2013) The developmental epigenomics toolbox: ChIP-seq and MethylCap-seq profiling of early zebrafish embryos. Methods 62:207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney SA, Prasch AL, Heideman W, Peterson RE. (2006) Understanding dioxin developmental toxicity using the zebrafish model. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 76:7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Tao J, Bae Y, Jiang MM, Bertin T, Chen Y, Yang T, Lee B. (2013) Notch gain of function inhibits chondrocyte differentiation via Rbpj-dependent suppression of Sox9. J Bone Miner Res 28:649–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang EF, Pai CI, Wyatt M, Yan YL, Postlethwait J, Chung B. (2001) Two Sox9 genes on duplicated zebrafish chromosomes: expression of similar transcription activators in distinct sites. Dev Biol 231:149–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deigan KE, Li TW, Mathews DH, Weeks KM. (2009) Accurate SHAPE-directed RNA structure determination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:97–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley K, Zon LI. (2000) Zebrafish: a model system for the study of human disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev 10:252–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esain V, Postlethwait JH, Charnay P, Ghislain J. (2010) FGF-receptor signalling controls neural cell diversity in the zebrafish hindbrain by regulating olig2 and sox9. Development 137:33–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatica A, Bozzoni I. (2014) Long non-coding RNAs: new players in cell differentiation and development. Nat Rev Genet 15:7–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuyama K, Kawaguchi Y, Akiyama H, Horiguchi M, Kodama S, Kuhara T, Hosokawa S, Elbahrawy A, Soeda T, Koizumi M, et al. (2011) Continuous cell supply from a Sox9-expressing progenitor zone in adult liver, exocrine pancreas and intestine. Nat Genet 43:34–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia GR, Noyes PD, Tanguay RL. (2016) Advancements in zebrafish applications for 21st century toxicology. Pharmacol Ther 161:11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodale BC, La Du J, Tilton SC, Sullivan CM, Bisson WH, Waters KM, Tanguay RL. (2015) Ligand-specific transcriptional mechanisms underlie aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated developmental toxicity of oxygenated PAHs. Toxicol Sci 147:397–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodale BC, La Du JK, Bisson WH, Janszen DB, Waters KM, Tanguay RL. (2012) AHR2 mutant reveals functional diversity of aryl hydrocarbon receptors in zebrafish. PLoS One 7:e29346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutschner T, Diederichs S. (2012) The hallmarks of cancer: a long non-coding RNA point of view. RNA Biol 9:703–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn ME, Karchner SI, Shapiro MA, Perera SA. (1997) Molecular evolution of two vertebrate aryl hydrocarbon (dioxin) receptors (AHR1 and AHR2) and the PAS family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:13743–13748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldin CE, LaBonne C. (2010) SoxE factors as multifunctional neural crest regulatory factors. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 42:441–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao N, Whitelaw ML. (2013) The emerging roles of AhR in physiology and immunity. Biochem Pharmacol 86:561–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry TR, Spitsbergen JM, Hornung MW, Abnet CC, Peterson RE. (1997) Early life stage toxicity of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 142:56–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofsteen P, Plavicki J, Johnson SD, Peterson RE, Heideman W. (2013) Sox9b is required for epicardium formation and plays a role in TCDD-induced heart malformation in zebrafish. Mol Pharmacol 84:353–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe K, Clark MD, Torroja CF, Torrance J, Berthelot C, Muffato M, Collins JE, Humphray S, McLaren K, Matthews L, et al. (2013) The zebrafish reference genome sequence and its relationship to the human genome. Nature 496:498–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Wang S, Ning Y, Lamb AN, Bartley J. (1999) Autosomal XX sex reversal caused by duplication of SOX9. Am J Med Genet 87:349–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Shui X, He Y, Xue Y, Li J, Li G, Lei W, Chen C. (2015) AhR expression and polymorphisms are associated with risk of coronary arterial disease in Chinese population. Sci Rep 5:8022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo A, Denduluri S, Zhang B, Wang Z, Yin L, Yan Z, Kang R, Shi LL, Mok J, Lee MJ, et al. (2014) The versatile functions of Sox9 in development, stem cells, and human diseases. Genes Dis 1:149–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karabiber F, McGinnis JL, Favorov OV, Weeks KM. (2013) QuShape: rapid, accurate, and best-practices quantification of nucleic acid probing information, resolved by capillary electrophoresis. RNA 19:63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik K, Leonard VE, Kv S, Lalwani MK, Jalali S, Patowary A, Joshi A, Scaria V, Sivasubbu S. (2013) Dynamic expression of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in adult zebrafish. PLoS One 8:e83616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettleborough RN, Busch-Nentwich EM, Harvey SA, Dooley CM, de Bruijn E, van Eeden F, Sealy I, White RJ, Herd C, Nijman IJ, et al. (2013) A systematic genome-wide analysis of zebrafish protein-coding gene function. Nature 496:494–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Cordero P, Das R, Yoon S. (2013) HiTRACE-Web: an online tool for robust analysis of high-throughput capillary electrophoresis. Nucleic Acids Res 41:W492–W498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kladwang W, VanLang CC, Cordero P, Das R. (2011) A two-dimensional mutate-and-map strategy for non-coding RNA structure. Nat Chem 3:954–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleindienst A, Dunbar JG, Glisson R, Okuno K, Marmarou A. (2006) Effect of dimethyl sulfoxide on blood-brain barrier integrity following middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien) 96:258–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht AL, Goodale BC, Truong L, Simonich MT, Swanson AJ, Matzke MM, Anderson KA, Waters KM, Tanguay RL. (2013) Comparative developmental toxicity of environmentally relevant oxygenated PAHs. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 271:266–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht AL, Truong L, Simonich MT, Tanguay RL. (2017) Developmental benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P) exposure impacts larval behavior and impairs adult learning in zebrafish. Neurotoxicol Teratol 59:27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn A, Rutkowski TP, Liu Z, Mirando AJ, Zuscik MJ, O’Keefe RJ, Hilton MJ. (2015) Notch signaling controls chondrocyte hypertrophy via indirect regulation of Sox9. Bone Res 3:15021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 25:402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz R, Bernhart SH, Höner Zu Siederdissen C, Tafer H, Flamm C, Stadler PF, Hofacker IL. (2011) ViennaRNA package 2.0. Algorithms Mol Biol 6:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini S, Bernoth K, Main H, Ortega GD, Lendahl U, Just U, Schwanbeck R. (2013) A critical role for Sox9 in notch-induced astrogliogenesis and stem cell maintenance. Stem Cells 31:741–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheu A, Collado M, Wise C, Manterola L, Cekaite L, Tye AJ, Canamero M, Bujanda L, Schedl A, Cheah KS, et al. (2012) Oncogenicity of the developmental transcription factor Sox9. Cancer Res 72:1301–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Sunkin SM, Mehler MF, Mattick JS. (2008) Specific expression of long noncoding RNAs in the mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105:716–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohba S, He X, Hojo H, McMahon AP. (2015) Distinct transcriptional programs underlie Sox9 regulation of the mammalian chondrocyte. Cell Reports 12:229–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardridge WM. (2005) The blood-brain barrier: bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRx 2:3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plavicki JS, Baker TR, Burns FR, Xiong KM, Gooding AJ, Hofsteen P, Peterson RE, Heideman W. (2014) Construction and characterization of a sox9b transgenic reporter line. Int J Dev Biol 58:693–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postlethwait J, Amores A, Cresko W, Singer A, Yan YL. (2004) Subfunction partitioning, the teleost radiation and the annotation of the human genome. Trends Genet 20:481–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasch AL, Tanguay RL, Mehta V, Heideman W, Peterson RE. (2006) Identification of zebrafish ARNT1 homologs: 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin toxicity in the developing zebrafish requires ARNT1. Mol Pharmacol 69:776–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett J, Athwal V, Roberts N, Hanley NA, Hanley KP. (2011) Understanding the role of SOX9 in acquired diseases: lessons from development. Trends Mol Med 17:166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn JJ, Chang HY. (2016) Unique features of long non-coding RNA biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Genet 17:47–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider AJ, Branam AM, Peterson RE. (2014) Intersection of AHR and Wnt signaling in development, health, and disease. Int J Mol Sci 15:17852–17885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CE, Wynn SL, Sesay A, Cruz C, Cheung M, Gomez Gaviro MV, Booth S, Gao B, Cheah KS, Lovell-Badge R, et al. (2010) SOX9 induces and maintains neural stem cells. Nat Neurosci 13:1181–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon MD. (2013) Capture hybridization analysis of RNA targets (CHART). Curr Protoc Mol Biol 101:21.25.1–21.25.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitsbergen JM, Kent ML. (2003) The state of the art of the zebrafish model for toxicology and toxicologic pathology research—advantages and current limitations. Toxicol Pathol 31:62–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolt CC, Wegner M. (2010) SoxE function in vertebrate nervous system development. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 42:437–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thisse C, Thisse B. (2008) High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat Protoc 3:59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong L, Harper SL, Tanguay RL. (2011) Evaluation of embryotoxicity using the zebrafish model, in Drug Safety Evaluation: Methods and Protocols (Gautier JC, ed) pp 271–279, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner DH, Mathews DH. (2010) NNDB: the nearest neighbor parameter database for predicting stability of nucleic acid secondary structure. Nucleic Acids Res 38:D280–D282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasa SM, Guex N, Wilkinson KA, Weeks KM, Giddings MC. (2008) ShapeFinder: a software system for high-throughput quantitative analysis of nucleic acid reactivity information resolved by capillary electrophoresis. RNA 14:1979–1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezina CM, Lin TM, Peterson RE. (2009) AHR signaling in prostate growth, morphogenesis, and disease. Biochem Pharmacol 77:566–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall RJ, Fernandes A, Rose M, Bell DR, Mellor IR. (2015) Characterisation of chlorinated, brominated and mixed halogenated dioxins, furans and biphenyls as potent and as partial agonists of the Aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Environ Int 76:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. (2007) The Zebrafish Book. A Guide for the Laboratory Use of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio), 5th ed, University of Oregon Press, Eugene, OR. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong KM, Peterson RE, Heideman W. (2008) Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated down-regulation of sox9b causes jaw malformation in zebrafish embryos. Mol Pharmacol 74:1544–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan YL, Willoughby J, Liu D, Crump JG, Wilson C, Miller CT, Singer A, Kimmel C, Westerfield M, Postlethwait JH. (2005) A pair of Sox: distinct and overlapping functions of zebrafish sox9 co-orthologs in craniofacial and pectoral fin development. Development 132:1069–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu MY, Gasperowicz M, Chow RL. (2013) The expression of NOTCH2, HES1 and SOX9 during mouse retinal development. Gene Expr Patterns 13:78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]