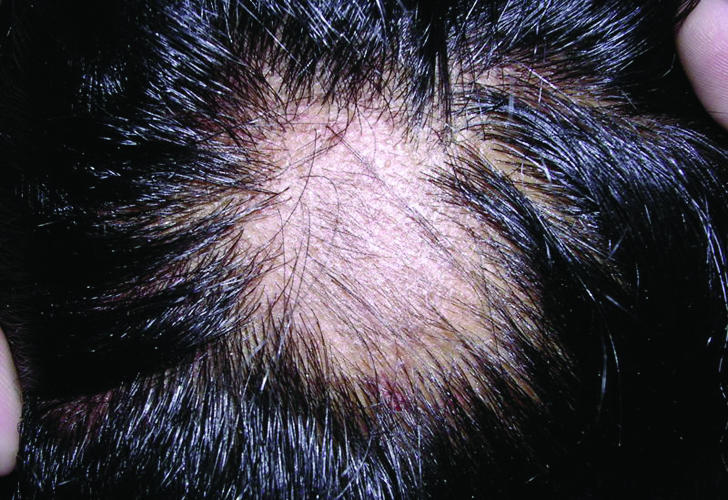

A 12 year old boy presented with two patches of hair loss on his scalp (figure). A clinical and histopathological diagnosis of trichotillomania was made. On follow up after taking a detailed history, the boy revealed that the hair was being pulled by an abusive teacher during tuition after school. I found two more children similarly abused by the teacher. I discuss the importance of this under-recognised pattern of child abuse and its similarity to trichotillomania.

Figure 1.

Localised patch of hair loss on the scalp

Child abuse has varied manifestations. Physical abuse of a child often results in identifiable dermatological signs, which can pinpoint the diagnosis. Abuse can closely resemble other dermatoses, however, resulting in diagnostic errors.

Trichotillomania is a condition currently classified as an impulse control disorder, which is characterised by repetitive pulling of one's own hair resulting in alopecia.

Case report

A 12 year old boy was referred by his family physician to the dermatology outpatient department with a complaint of partial hair loss on his scalp that was noticed one week before. On examination, there were two patches of partial alopecia on the temporovertical scalp measuring 2 cm by 2 cm and 3 cm by 3 cm. The hair shafts were broken off at different levels and there was no evidence of scarring. The scalp was not tender or bruised. A hair pull test did not find his hair easy to pluck and hair shaft microscopy was normal. A potassium hydroxide preparation from the lesional skin did not show any fungal elements. A skin biopsy from one of the patches found many empty hair bulbs without any inflammation or scarring. Several catagen hair follicles were also identified.

Based on these clinical and histopathological findings, I diagnosed him as having trichotillomania and referred him for psychiatric evaluation. The parents refused psychiatric help, however, and insisted that the child had never pulled his hair. When this topic was broached with the child in the absence of his parents, he denied any knowledge of the possible cause of the hair loss. Several dermatology consultations later, the child volunteered that the hair was being pulled by a teacher who gave him private tuition after school hours. I informed his parents and covert surveillance of the teacher confirmed physical abuse in the form of twisting and pulling of hair. Inquiries to all students being tutored by the teacher found two more cases. I informed the school authorities, and the teacher was referred for psychiatric evaluation. The boy stopped the private tuition, which resulted in full regrowth of hair in both patches within four weeks.

Discussion

Skin lesions are the most common presentation of physical abuse and suggestive or confirmative dermatological signs may be present in up to 90% of all abused children.1 The most common dermatological signs of child abuse are bruises and abrasions then lacerations, scratches, soft tissue swellings, strap marks, haematomas, burns, and bites.2 Hair loss as a manifestation of child abuse is usually described in association with underlying scalp bruising or tenderness.3 In this boy, however, the force applied by the perpetrator was insufficient to cause any damage to the underlying soft tissue: localised hair loss was the sole manifestation of abuse. Also, since the cause of alopecia was the same as in trichotillomania—mechanical twisting and pulling of hair—the clinical and histopathological features were identical. And the usual clues indicating child abuse—delay in seeking help, inconsistent history, and lack of concern by parents—were not present, leading to initial misdiagnosis.

Trichotillomania is often associated with young children and adolescents,4 and the average age of onset of trichotillomania is 12 years.5 It is characterised by irregular, non-scarring, focal patches of alopecia, often on the crown, occipital, or parietal region of the scalp. Hair loss tends to occur on the contralateral side of the body from the dominant hand,6 and the patches of hair loss contain broken hairs of varying length. Tinea capitis, traction alopecia, and alopecia areata are the usual dermatoses that may mimic trichotillomania.7

The background in which trichotillomania develops is quite similar to the risk factors for child abuse. In children, trichotillomania often starts at times of psychosocial stress within the family unit such as a disturbed mother-child relationship, hospitalisations, periods of separation, or developmental problems.8 Recently, a strong relationship of family chaos during childhood and trichotillomania has also been reported, in which 86% of women with trichotillomania reported a history of violence—for example, sexual assault or rape—concurrent with the onset of trichotillomania.9 Similar factors, such as violence between parents or siblings, disturbed parent-child interaction, recent death, or illness in the family have been well described as criteria for suspecting child abuse.10

A child with this background who presents with mechanical hair loss, may have either condition. Without witnesses to confirm hair pulling by the child, the possibility of child abuse should be kept in mind and initial assessment should aim to confirm only the diagnosis of mechanical alopecia. Other causes of mechanical alopecia—traction alopecia due to unusual hairstyles or hair accessories11 or localised hair shaft abnormalities12—should then be ruled out. Subsequently, attempts to find the person responsible for pulling the hair should be made with the objective of getting disclosure by the child. This may require collaboration with the family doctor or pediatrician.

The case exemplifies the need to keep a high index of suspicion not to miss child abuse. In cases of localised hair loss in children, especially if a mechanical alopecia—trichotillomania or traction alopecia—is being considered, the possibility of child abuse should also be kept in mind while examining the patient.

Localised hair loss in a child may be the sole sign of child abuse

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

Contributors: AS is the sole contributor.

References

- 1.Raimer BG, Raimer SS, Hebeler JR. Cutaneous signs of child abuse. J Am Acad Dermatol 1981;5: 203-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson CF. Inflicted injury versus accidental injury. Pediatr Clin N Am 1990;37: 791-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy CTC. Mechanical and thermal injury. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, Breathnach SM, eds. Textbook of dermatology. 6th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 1999: 777.

- 4.Hallopeau H. Alopecie par grattage (trichomanie ou trichotillomanie). Ann Dermatol Syphiligr (Paris) 1889;10: 440-1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen LJ, Stein DJ, Simeon D, Spadaccini E, Rosen J, Aronowitz B, et al. Clinical profile, comorbidity, and treatment history in 123 hair pullers: a survey study. J Clin Psychiatry 1995;56: 319-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mehregan AH. Trichotillomania: a clinicopathologic study. Arch Dermatol 1970;102: 129-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider D, Janninger CK. Trichotillomania. Cutis 1994;53: 289-90, 294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oranje AP, Peereboom-Wynia JD, Raeymaecker DM. Trichotillomania in childhood. J Am Acad Dermatol 1986;15: 614-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boughn S, Holdom JJ. The relationship of violence and trichotillomania. J Nurs Scholarsh 2003;35: 165-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duarte AM, Pruksachatkunakorn C, Schachner LA. Life threatening dermatoses in pediatric dermatology. Adv Dermatol 1995;10: 329-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trueb RM. “Chignon alopecia”: a distinctive type of nonmarginal traction alopecia. Cutis 1995;55: 178-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith RA, Ross JS, Bunker CB. Localized trichorrhexis nodosa. Clin Exp Dermatol 1994;19: 441-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]