Abstract

Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the most prevalent cystic kidney disease, with approximately half of the patients reaching end-stage renal disease by the age of 60. Tolvaptan prevents renal cyst growth by inhibiting intracellular cyclic AMP and is recommended for patients with ADPKD. Reports of thrombotic complications with tolvaptan have been limited. We report a case of a 60-year-old man who developed thromboembolisms during tolvaptan treatment for ADPKD. The patient started tolvaptan in July 2014. He was brought to our hospital in February 2015 with a sudden onset of dyspnea and chest pain after 6 days of persistent watery diarrhea. Blood tests revealed enhanced coagulation and fibrinolysis, and contrast-enhanced computed tomography confirmed the presence of multiple thromboembolisms. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) with acute pulmonary and lower extremity thrombi was diagnosed, and the patient was immediately admitted. Tolvaptan was discontinued on admission, and intravenous fluid loading and monteplase were started. Subsequently, chest pain and dyspnea resolved, with thrombi resolution occurring by day 14; the patient was discharged on day 18 in stable condition. VTE was attributed to continued tolvaptan during diarrhea and dehydration; tolvaptan itself was not associated with enhanced coagulability. Dehydrated patients with ADPKD, such as the patient in this case, are at an increased risk for thrombus formation. Proper education should be provided to maintain appropriate fluid status and discontinue tolvaptan upon volume depletion.

Keywords: Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease, Pulmonary thromboembolism, Venous thromboembolism, Tolvaptan, Dehydration

Introduction

Autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the most prevalent cystic kidney disease. As the number of cysts increases in both kidneys, renal function progressively deteriorates and approximately half of the patients reach end-stage renal disease by the age of 60 [1]. Tolvaptan, a vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist, selectively blocks vasopressin V2 receptors and inhibits production of cyclic adenosine 3, 5-monophosphate (cAMP). With the inhibitory mechanism on intracellular cAMP, tolvaptan is expected to prevent renal cyst growth [2]. Because there is no other effective pharmacological treatment at present, tolvaptan is recommended for patients with ADPKD who have a total kidney volume of 750 ml or more with progressive renal volume expansion [3]. The patients treated with tolvaptan for ADPKD are encouraged to increase their fluid intake to prevent dehydration. Reports on the thrombotic complication with tolvaptan have been limited at present. We report a case who developed acute pulmonary thromboembolism during treatment with tolvaptan for ADPKD.

Case report

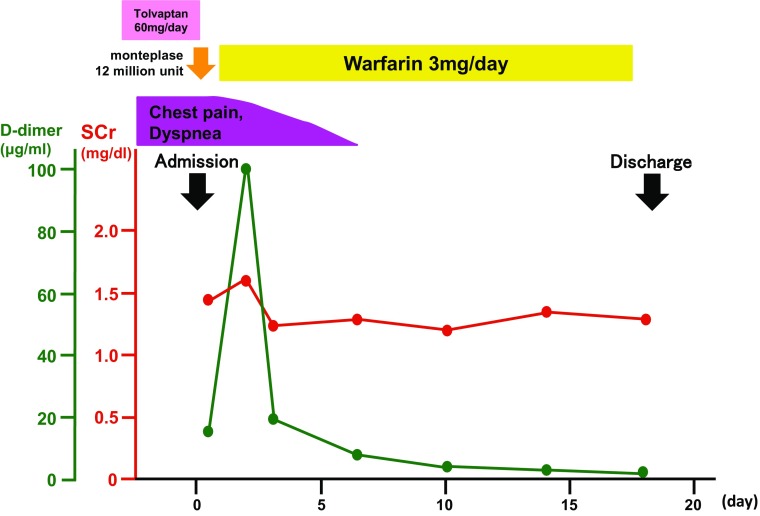

Sixty-year-old man was diagnosed as ADPKD at the age of 47. Since then, his renal function had gradually deteriorated as the total kidney volume slowly increased. With his consent, administration of tolvaptan at a dose of 60 mg/day was started in July, 2014. The appropriate drug adherence had been maintained. He described no dyspnea or edema of the lower extremities, and d-dimer was within normal range in January, 2015. In February, 2015, he developed persistent watery diarrhea. His wife also had watery diarrhea at the same time. During that period, he continued taking tolvaptan and more than 2L of fluid daily. Six days after the onset of diarrhea, he was brought to our hospital by ambulance with sudden onset of dyspnea and chest pain. Tachycardia of 120 bpm and marked hypoxemia indicated by an oxygen saturation (SpO2) level of 90% on ambient air were observed. His body weight was 0.7 kg below his usual weight. The oral cavity was markedly dry. The lung sounds were normal, and the second heart sound was accentuated. Enlarged liver and kidneys were palpated, and both legs showed mild edema. Blood tests revealed enhancement of coagulation and fibrinolysis with a fibrin degradation product (FDP) level of 52.4 µg/mL (reference range: less than 5.0 µg/mL) and a d-dimer of 18.4 µg/mL (reference range: less than 0.7 µg/mL). Acute kidney injury was also present with blood urea nitrogen (BUN) of 38 mg/dl, serum creatinine (SCr) of 1.45 mg/dL (Table 1). These values were within normal range at the latest office visit. AKI were attributed to volume depletion both due to diarrhea and inadequate fluid intake. The chest X-ray showed mild pulmonary artery expansion. The electrocardiogram showed right bundle branch block and a negative T wave in V1–3. Echocardiogram revealed a tricuspid valve regurgitation with pressure gradient of 40 mmHg. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) confirmed the presence of multiple areas of thromboembolism in the right pulmonary arterial trunk, left pulmonary arterial branches, and the veins beyond the popliteal vein of both legs. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) with acute pulmonary and lower extremity thrombi was diagnosed, and the patient was immediately admitted. Diarrhea had improved by the time of admission, and tolvaptan was discontinued on admission. Intravenous fluid loading and 1.2 million units of monteplase were started. Subsequently, the chest pain and dyspnea resolved. On hospital day 2, warfarin was started with a target prothrombin time-international ratio (PT-INR) of 2.0. Although the patient was closely examined for the presence or absence of underlying diseases associated with thrombosis, there were no particular abnormal test results to be noted, and he was deemed unlikely to have such diseases (Table 1). Contrast-enhanced CT angiogram performed on hospital day 14 revealed resolution of bilateral pulmonary artery thrombi and imaging of pulmonary blood flow demonstrated normal blood flow distribution bilaterally (Fig. 1). The tricuspid valve regurgitation pressure gradient, as measured by echocardiography, had also decreased to 23 mmHg. He discharged on hospital day 18 with stable medical condition (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Laboratory findings on admission

| Urinalysis | |

| Specific gravity | 1.010 |

| pH | 6.0 |

| Protein | Negative |

| Glucose | Negative |

| Ketones | Negative |

| Occult blood | Negative |

| RBC | <1/HPF |

| WBC | <1/HPF |

| Hyaline cast | Positive |

| Urine biochemistry | |

| β2-MG | 469 μg/L |

| Osmolality | 163 mOsm/kgH2O |

| Hematology | |

| WBC | 7500/μL |

| RBC | 422 × 104/μL |

| Hemoglobin | 16.1 g/dL |

| Hematocrit | 45.9% |

| Platelets | 11.8 × 104/μL |

| Coagulation | |

| PT-INR | 0.97 |

| APTT | 24.4 s |

| FDP | 52.4 μg/mL |

| d-Dimer | 18.4 μg/mL |

| Protein C activity | 69% |

| Protein S activity | 141.0% |

| TAT complex | >60.0 ng/mL |

| Biochemistry | |

| Total protein | 6.4 g/dL |

| Albumin | 3.9 g/dL |

| AST | 23 IU/L |

| ALT | 15 IU/L |

| LDH | 263 IU/L |

| CK | 90 IU/L |

| ALP | 113 IU/L |

| γ-GTP | 34 IU/L |

| Total-Bilirubin | 0.9 mg/dL |

| Glucose | 95 mg/dL |

| Uric acid | 7.7 mg/dL |

| BUN | 38 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 1.45 mg/dL |

| Estimated-GFR | 39.9 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

| Sodium | 147 mEq/L |

| Potassium | 3.6 mEq/L |

| Chloride | 112 mEq/L |

| Calcium (adjusted) | 9.2 mg/dL |

| Phosphorus | 2.4 mg/dL |

| Serology | |

| CRP | 0.6 mg/dl |

| ANA | Negative |

| Anti-CL antibody | <1.2 IU/mL |

| Lupus anticoagulant | 1.01 |

| Arterial blood gas analysis (room air) | |

| pH | 7.346 |

| PaO2 | 63.7 mmHg |

| PaCO2 | 30.1 mmHg |

| HCO3 − | 19.9 mEq/L |

| Base excess | −2.9 mEq/L |

RBC red blood cell, WBC white blood cell, MG microglobulin, PT-INR prothrombin time-international normalized ratio, APTT activated partial thromboplastin time, FDP fibrinogen degradation products, TAT thrombin–antithrombin, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, LDH lactate dehydrogenase, CK creatine kinase, ALP alkaline phosphatase, GTP guanosine triphosphate, BUN blood urea nitrogen, GFR glomerular filtration rate, CRP C-reactive protein, ANA antinuclear antibodies, CL cardiolipin

Fig. 1.

Contrast-enhanced and lung perfusion computed tomography images before and after treatment. The upper and the lower images were taken before and after treatment, respectively. The pretreatment images show lack of enhancement in the right pulmonary arterial trunk and left pulmonary arterial branches (arrows) and lack of right lung perfusion (arrowheads). The lack of enhancement is not observed after treatment

Fig. 2.

Clinical course

Discussion

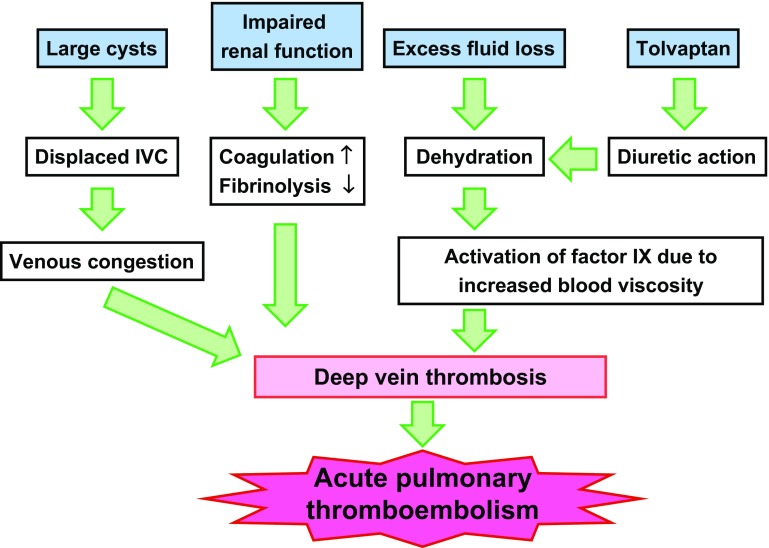

In this case, the onset of VTE is attributed to continued ingestion of tolvaptan, while the patient developed persistent watery diarrhea and dehydration. As of the end of April 2016, two cases (including current case) of pulmonary thromboembolism associated with tolvaptan have been reported to Samsca Postmarketing Surveillance according to Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Regarding the pathogenesis of thrombosis in these cases, dehydration is through to be a main culprit for hypercoagulable state. Dehydration increases the hematocrit and blood viscosity both of which could induce thrombotic tendency [4]. Moreover, elevated hematocrit levels are reported to promote activation of factor IX (an intrinsic factor for coagulation cascade) by erythroelastase IX (factor IX-activating enzyme) in erythrocytes, which could further enhance the coagulation pathway [5, 6]. In addition, patients with reduced renal function are more likely to develop pulmonary thromboembolism than those with normal kidney function [7]. Possible mechanisms for the phenomenon include enhanced activation of factor XIIa, factor VIIa, and fibrinogen, as well as inhibition of von Willebrand factor and tissue plasminogen activator in the patients with reduced renal function [8, 9]. There is also a report of a rare case of ADPKD patient in which a thrombus formation was observed in the inferior vena cava (IVC) due to the compression of IVC by huge renal cysts [10]. In the current case, no compression or displacement of IVC by cysts was observed.

Whether tolvaptan itself could induce thrombotic tendency was evaluated. Normally, when vasopressin binds to the vasopressin V2 receptors, cAMP is activated, and vascular endothelial cells release von Willebrand factor, both of which could contribute to increased coagulation cascade [11]. Thus, vasopressin is often used for hemostasis in the treatment of von Willebrand disease, mild hemophilia, and chronic kidney disease (CKD) [12, 13]. Tolvaptan inhibits the release of von Willebrand factor from vascular endothelial cells by its antagonistic effect on the vasopressin V2 receptors and may rather reduce the hemostatic capacity. Therefore, tolvaptan itself is not considered to be associated with enhanced coagulability [14].

Whether the episode of diarrhea in this case was associated with tolvaptan remains unclear. As of the end of April 2016, nine cases of diarrhea and ten cases of constipation associated with tolvaptan have been reported to Samsca Postmarketing Surveillance. The mechanism of gastrointestinal symptoms by tolvaptan is not fully understood, but inhibition of colonic aquaporin-2 by tolvaptan followed by reduction in water reabsorption might be responsible for the development of diarrhea [15]. In this case, however, it seems to be unusual when tolvaptan causes diarrhea for the first time after 7 months of administration. Diarrhea in his wife almost the same time as the patient strongly suggests infectious origin of the diarrhea in this case.

Dehydrated patients with ADPKD, such as the patient in this case, are at increased risk of thrombus formation. This case indicates the importance of sick-day management for the patients on tolvaptan. Proper and sufficient information to maintain appropriate fluid status and to stop taking tolvaptan should be provided, while the patients develope volume depletion (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Pathogenesis of thromboembolism in ADPKD. Patients with ADPKD on tolvaptan face increased thrombotic risk due to several factors associated with the anatomical, physiological, pathological, and pharmacological features of ADPKD. ADPKD autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease, IVC inferior vena cava, SCr serum creatinine

In conclusion, although tolvaptan could be effective in retarding the progression of ADPKD, the patients on tolvaptan face the increased risk of thromboembolism once they developed volume depletion and dehydration. Appropriate sick-day advice should be given to all the patients taking tolvaptan for ADPKD.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Yoshihiko Saito received lecture fees from Merck, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Novartis Pharma KK, Daiichi Sankyo Company, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corp, Pfizer Japan, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, and research funding from Japan Heart Foundation and the Naito Foundation. Dr. Saito belongs to the endowed Department (the Department of Regulatory Medicine of Blood Pressure) sponsored by Merck. Yasuhiro Akai received lecture fees from Dainippon-Sumitomo Pharmaceutical Company and obtained research funding from Nara Red Cross Blood Distributing Center. Other authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Higashihara E, Nutahara K, Kojima M, Tamakoshi A, Yoshiyuki O, Sakai H, et al. Prevalence and renal prognosis of diagnosed autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in Japan. Nephron. 1998;80:421–427. doi: 10.1159/000045214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gattone VH, 2nd, Wang X, Harris PC, Torres VE. Inhibition of renal cystic disease development and progression by a vasopressin V2 receptor antagonist. Nat Med. 2003;9:1323–1326. doi: 10.1038/nm935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, Gansevoort RT, Grantham JJ, Higashihara E, et al. Tolvaptan in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2407–2418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yasaka M, Beppu S. Hypercoagulability in the left atrium: Part II: Coagulation factors. J Heart Valve Dis. 1993;2:25–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawakami S, Kaibara M, Kawamoto Y, Yamanaka K. Rheological approach to the analysis of blood coagulation in endothelial cell-coated tubes: activation of the intrinsic reaction on the erythrocyte surface. Biorheology. 1995;32:521–536. doi: 10.1016/0006-355X(95)00030-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwata H, Kaibara M. Activation of factor IX by erythrocyte membranes causes intrinsic coagulation. Blood coagulation and fibrinolysis. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2002;13:489–496. doi: 10.1097/00001721-200209000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar G, Sakhuja A, Taneja A, Majumdar T, Patel J, Whittle J, et al. Pulmonary embolism in patients with CKD and ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:1584–1590. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00250112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shlipak MG, Fried LF, Crump C, Bleyer AJ, Manolio TA, Tracy RP, et al. Elevations of inflammatory and procoagulant biomarkers in elderly persons with renal insufficiency. Circulation. 2003;107:87–92. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000042700.48769.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hrafnkelsdottir T, Ottosson P, Gudnason T, Samuelsson O, Jern S. Impaired endothelial release of tissue-type plasminogen activator in patients with chronic kidney disease and hypertension. Hypertension. 2004;44:300–304. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000137380.91476.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maeda T, Uchida Y, Oyamada K, Nakajima F. Thrombosis in inferior vena cava due to enlarged renal cysts in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Intern Med (Tokyo. Japan) 2010;49:1891–1894. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaufmann JE, Oksche A, Wollheim CB, Gunther G, Rosenthal W, Vischer UM. Vasopressin-induced von Willebrand factor secretion from endothelial cells involves V2 receptors and cAMP. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:107–116. doi: 10.1172/JCI9516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Federici AB. The use of desmopressin in von Willebrand disease: the experience of the first 30 years (1977–2007) Haemophilia. 2008;14(Suppl 1):5–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2516.2007.01610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rose EH, Aledort LM. Nasal spray desmopressin (DDAVP) for mild hemophilia A and von Willebrand disease. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:563–568. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-7-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blumenfeld JD, Tepler J, Mauer A, Coller B, Bichet DG, Smith B. Tolvaptan inhibition of desmopressin effects on coagulation factors in a patient with decreased von Willebrand factor and polycystic kidney disease. Blood. 2011;118:474–476. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-347328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen C, Chen RP, Lin HH, Zhang WY, Huang XL, Huang ZM. Tolvaptan regulates aquaporin-2 and fecal water in cirrhotic rats with ascites. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(12):3363–3371. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i12.3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]