Abstract

Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma is an extremely rare tumor. The diagnosis is difficult, and its etiologic factors have not been clarified. A 63-year-old woman with numerous cysts in her kidneys and liver was diagnosed with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD). Several members of her family also had ADPKD. She underwent treatment with tolvaptan to inhibit cyst growth and slow the decline in kidney function. Eight months after the start of the therapy, she was hospitalized with fatigue and fever of unknown origin. Diagnostic imaging showed a very large hepatic tumor, and histologic examination of a fine-needle biopsy specimen revealed the tumor to be malignant. Differentiation between carcinoma and sarcoma was difficult based on the histological findings. The tumor was thought to be excisable; therefore, hepatic resection was attempted. At the time of surgery, as the tumor had grown larger than when imaged, complete resection was impossible. However, a part of the tumor was resected. Histopathological and immunohistological examinations of the surgical specimen confirmed a primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma. Whether the tumor was associated with the presence of ADPKD remains unclear, however, this is the first report of the combination of these two diseases in a patient.

Keywords: Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma, Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

Introduction

Because of the rarity of primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma, our understanding of the tumor is limited. Its etiologic factors have not been clarified. The diagnosis is often difficult due to non-specific presentations, laboratory studies, and images. In addition, the standard of care has not been established. Its prognosis is thought to be poor.

We herein report a case of primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma (PHL) in a patient with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD).

Case report

A 63-year-old woman had a 20-year history of numerous cysts in her kidneys and liver (Fig. 1a). Her father, two of her father’s sisters, her sister, and two of her cousins had been diagnosed with ADPKD. Based on her images of kidneys and family history, she was diagnosed with ADPKD. With the exception of ADPKD, the patient had no medical history, including previous liver disease or alcoholic abuse. Tolvaptan (60 mg/day) therapy was begun in our hospital to inhibit cyst growth and slow the decline of kidney function. Eight months after the start of the therapy, the patient was referred to our department with a chief complaint of general fatigue and fever of unknown origin for the previous few months. Physical examination was unremarkable, and laboratory analysis revealed anemia and a slightly high leukocyte count, platelet count, and C-reactive protein concentration. Impaired renal function due to ADPKD and elevated concentrations of alkaline phosphatase, lactate dehydrogenase, and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase were observed. α-fetoprotein, CA 19-9, carcinoembryonic antigen, CA125, and PIVKA-II were almost normal. The soluble IL-2 receptor concentration was slightly high. Hepatitis C virus antibody and hepatitis B surface antigen were negative. Indocyanine green at 15 min was 8% (Table 1).

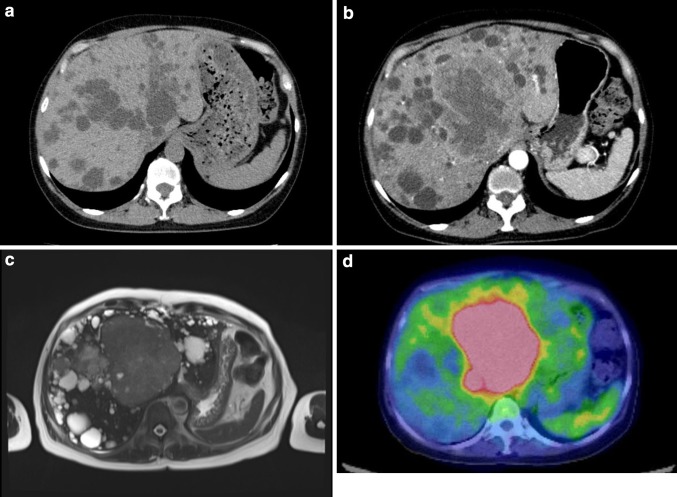

Fig. 1.

a Computed tomography at the start of Tolvaptan therapy. Numerous cysts were recognized in her liver. However, a tumor was not seen. b Enhanced computed tomography. A large tumor is present in the left lobe, and the margin of the mass is enhanced. c T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging of the liver. Slightly high signal density is present in the left lobe. d 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography–computed tomography. A lesion with higher 18F-FDG uptake is present on the liver; this lesion corresponds to the tumor revealed by computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging

Table 1.

Laboratory data

| Urine | Chemistry | Serology | |||

| Protein | (2+) | TP | 6.7 g/dL | α-fetoprotein | 1.7 ng/mL |

| Occult blood | (−) | Alb | 2.9 g/dL | PIVKA-II | <10 mAU/mL |

| RBC | 0/HPF | T-bil | 0.2 mg/dL | CA19-9 | 31.7 U/mL |

| WBC | 0–2/HPF | AST | 37 U/L | CA125 | 44.1 U/mL |

| ALT | 28 U/L | Soluble IL-2R | 848 U/mL | ||

| LDH | 306 U/L | CEA | 1.9 ng/mL | ||

| ALP | 634 U/L | proGRP | 116.8 pg/mL | ||

| γ-GTP | 201 U/L | NSE | 42.4 ng/mL | ||

| Blood | Amy | 113 U/L | SCCag | 1.5 ng/min | |

| WBC | 9930/μL | CK | 28 U/L | HBSag | Negative |

| Neut | 82.5% | BUN | 34.4 mg/DL | HCVab | Negative |

| Lymp | 11.1% | Cr | 1.78 mg/DL | ||

| Mono | 4.7% | Na | 142 mEq/L | ||

| Eosi | 1.4% | K | 5.7 mEq/L | ||

| Baso | 0.3% | Cl | 106 mEq/L | ||

| RBC | 319 × 104/μL | Ca | 9.1 mEq/L | ||

| Hb | 9.0 g/dL | CRP | 6.30 mEq/L | ||

| Ht | 29.9% | PT | 11.5 s | ||

| Plt | 45.9 × 104/μL | PT-INR | 1.09 | ||

| ICG (15 min) | 8% | ||||

Besides multiple hepatic cysts due to ADPKD, an isodense mass of 10-cm diameter was newly discovered in the left hepatic lobe on abdominal computed tomography (CT). Contrast-enhanced CT showed that the margin of the mass was enhanced in the arterial to venous phase (Fig. 1b). On magnetic resonance imaging, the tumor showed slightly low signal intensity on T1-weighted imaging and slightly high signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging (Fig. 1c). A whole-body positron emission tomography–CT scan was conducted, and the tumor appeared as a lesion with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake (Fig. 1d). On the images, the tumor remained in her liver. In addition, any enlargement of lymph nodes and metastatic lesions was not recognized.

Although fine-needle aspiration was performed for a histological diagnosis, differentiation between carcinoma and sarcoma was difficult. The tumor was thought to be excisable; therefore, hepatic resection was attempted. However, at the time of surgery, as the tumor had grown larger than when imaged, complete resection was impossible. However, a part of the tumor was resected. In a short time after the operation, she died without additional treatments.

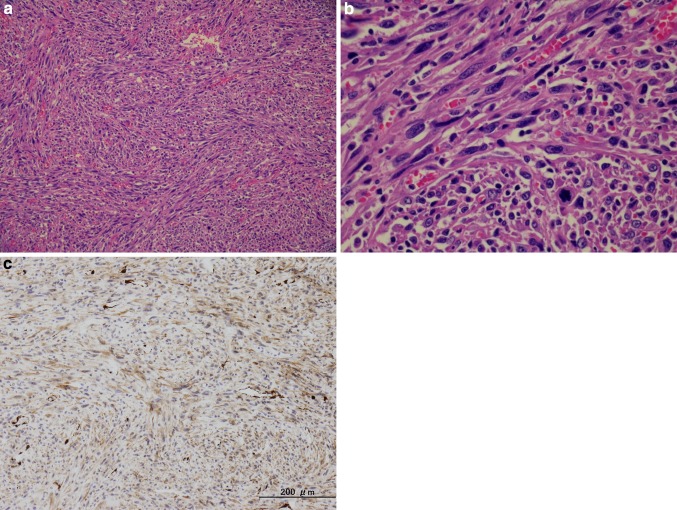

Microscopically, the tumor was composed of spindle cells with eosinophilic fibrillar cytoplasm. These cells were arranged in short intersecting fascicles (Fig. 2a). The nuclei were hyperchromatic, and mitotic figures were prominent (Fig. 2b). Immunohistochemical examination revealed that these spindle cells were positive for α-smooth muscle actin (Fig. 2c) and vimentin, but negative for factor VIII, CD31, desmin, S-100, HepPar-1, α-fetoprotein, and erythroblast transformation-specific-related gene. Based on these findings, we diagnosed the hepatic tumor as a poorly differentiated leiomyosarcoma. We also investigated the presence of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) by fluorescence in situ hybridization, but were unable to detect it. This eliminates the possibility of the smooth muscle neoplasms having been induced by EBV.

Fig. 2.

a Spindle tumor cells with eosinophilic fibrillar cytoplasm are arranged in short intersecting fascicles. b Nuclei were hyperchromatic, and mitotic figures were prominent. c Tumor cells were positive for α-smooth muscle actin

Discussion

Primary hepatic sarcoma constitutes only 0.2–2% of primary hepatic cancers [1–3]. Among these primary hepatic sarcomas, PHL comprises 6–16% [3, 4], making it an extremely rare tumor. PHL may develop from the smooth muscle cells of intrahepatic vascular structures or bile ducts [5]. However, its etiologic factors are not fully understood.

Previous reports have described the development of PHL in patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma [6, 7], gastric non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [8], hereditary retinoblastoma [9], immunosuppression due to renal or liver transplantation [10, 11], von Recklinghausen’s disease [12], cirrhosis due to hepatitis C virus [13], Behcet’s disease [14], acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [15–18], EBV [11, 17], use of Thorotrast [19], and multiple cancers [20].

To the best of our knowledge, no previous case reports have described the development of PHL in a patient with ADPKD. Various extrarenal complications have been reported in patients with ADPKD, such as intracranial aneurysms, diverticula, abdominal hernias, and valvular abnormalities [21]. However, ADPKD is not considered to be a risk factor for any cancer, so whether the ADPKD was associated with the PHL in the present case is unclear. In addition, our patient had received tolvaptan, which slows the growth of kidney cysts and the decline of kidney function [22]. However, no side effects of tolvaptan in the form of tumor development have been reported. In our case, the PHL may have developed incidentally. Although this case is very rare, we should pay attention to the fact that PHL can be arised in patients with ADPKD.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

All the authors have declared no competing interest.

Human and animal rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient in this report.

References

- 1.Maki HS, Hubert BC, Sajjad SM, Kirchner JP, Kuehner ME. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma. Arch Surg. 1987;122(10):1193–1196. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1987.01400220103020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan Primary liver cancer in Japan. Clinicopathologic features and results of surgical treatment. Ann Surg. 1990;211:277–287. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carriaga MT, Henson DE. Liver, gallbladder, extrahepatic bile ducts, and pancreas. Cancer. 1995;75:171–190. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950101)75:1+<171::AID-CNCR2820751306>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weitz J, Klimstra DS, Cymes K, Jarnagin WR, D’Angelica M, La Quaglia MP, Fong Y, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH, Dematteo RP. Management of primary liver sarcomas. Cancer. 2007;109:1391–1396. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shivathirthan N, Kita J, Iso Y, Hachiya H, Kyunghwa P, Sawada T, Kubota K. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma: case report and literature review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;3:148–152. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v3.i10.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giuliante F, Sarno G, Ardito F, Pierconti F. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in a young man after Hodgkin’s disease: diagnostic pitfalls and therapeutic challenge. Tumori. 2009;95:374–377. doi: 10.1177/030089160909500318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrozzi F, Bova D, Zangrandi A, Garlaschi G. Primary liver leiomyosarcoma: CT appearance. Abdom Imaging. 1996;21:157–160. doi: 10.1007/s002619900034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linares Torres P, Vivas Alegre S, Castañón López C, Domínguez Carbajo AB, Honrado Franco E, Espinel Díez J, Jorquera Plaza F, Olcoz Goñi JL. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in a patient with gastric non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;25:452–454. doi: 10.1016/S0210-5705(02)70286-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdelli N, Thiefin G, Diebold MD, Bouche O, Aucouturier JP, Zeitoun P. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the liver 37 years after successful treatment of hereditary retinoblastoma. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1996;20:502–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujita H, Kiriyama M, Kawamura T, Ii T, Takegawa S, Dohba S, Kojima Y, Yoshimura M, Kobayashi A, Ozaki S, Watanabe K. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in a woman after renal transplantation: report of a case. Surg Today. 2002;32:446–449. doi: 10.1007/s005950200073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brichard B, Smets F, Sokal E, Clapuyt P, Vermylen C, Cornu G, Rahier J, Otte JB. Unusual evolution of an Epstein-Barr virus-associated leiomyosarcoma occurring after liver transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2001;5:365–369. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3046.2001.00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maruta K, Sonoda Y, Saigo R, Yoshioka T, Fukunaga H. A patient with von Recklinghausen’s disease associated with polymyositis, asymptomatic pheochromocytoma, and primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 2004;41:339–343. doi: 10.3143/geriatrics.41.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuji M, Takenaka R, Kashihara T, Hadama T, Terada N, Mori H. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in a patient with hepatitis C virus-related liver cirrhosis. Pathol Int. 2000;50:41–47. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2000.00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon KM, Jang BK, Chung WJ, Park KS, Cho KB, Hwang JS, Kang KJ, Kang YN, Kwon JH. A case of primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma with intrahepatic and abdominal subcutaneous metastasis in Behcet’s disease. Korean. J Hepatol. 2005;11:386–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross JS, Del Rosario A, Bui HX, Sonbati H, Solis O. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma in a child with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:69–72. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90014-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metta H, Corti M, Trione N, Masini D, Monestes J, Rizzolo M, Carballido M. Primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma—a rare neoplasm in an adult patient with AIDS: second case report and literature review. J Gastrointest. Cancer. 2014;45:36–39. doi: 10.1007/s12029-013-9525-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chelimilla H, Badipatla K, Ihimoyan A, Niazi M. A rare occurrence of primary hepatic leiomyosarcoma associated with epstein barr virus infection in an AIDS patient. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2013;2013:691862. doi: 10.1155/2013/691862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith MB, Silverman JF, Raab SS, Towell BD, Geisinger KR. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of hepatic leiomyosarcoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;11:321–327. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840110403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shurbaji MS, Olson JL, Kuhajda FP. Thorotrast-associated hepatic leiomyosarcoma and cholangiocarcinoma in a single patient. Hum Pathol. 1987;18:524–526. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(87)80039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinoshita A, Sakon M, Monden M, Gotoh M, Kobayashi K, Okuda H, Kuroda C, Sakurai M, Okamura J, Mori T. Triple synchronous malignant tumors. Hepatic leiomyosarcoma, splenic hemangiosarcoma and sigmoid colon cancer. Case report. Acta Chir Scand. 1988;154(7–8):477–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luciano RL, Dahl NK. Extra-renal manifestations of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD): considerations for routine screening and management. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014;29:247–254. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Torres VE, Chapman AB, Devuyst O, Gansevoort RT, Grantham JJ, Higashihara E, Perrone RD, Krasa HB, Ouyang J, Czerwiec FS, TEMPO 3:4 Trial Investigators Tolvaptan in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:240718. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]