Abstract

Rationale: Asthma and obesity often occur together in children. It is unknown whether asthma contributes to the childhood obesity epidemic.

Objectives: We aimed to investigate the effects of asthma and asthma medication use on the development of childhood obesity.

Methods: The primary analysis was conducted among 2,171 nonobese children who were 5–8 years of age at study enrollment in the Southern California Children’s Health Study (CHS) and were followed for up to 10 years. A replication analysis was performed in an independent sample of 2,684 CHS children followed from a mean age of 9.7 to 17.8 years.

Measurements and Main Results: Height and weight were measured annually to classify children into normal, overweight, and obese categories. Asthma status was ascertained by parent- or self-reported physician-diagnosed asthma. Cox proportional hazards models were fitted to assess associations of asthma history with obesity incidence during follow-up. We found that children with a diagnosis of asthma at cohort entry were at 51% increased risk of developing obesity during childhood and adolescence compared with children without asthma at baseline (hazard ratio, 1.51; 95% confidence interval, 1.08–2.10) after adjusting for confounders. Use of asthma rescue medications at cohort entry reduced the risk of developing obesity (hazard ratio, 0.57; 95% confidence interval, 0.33–0.96). In addition, the significant association between a history of asthma and an increased risk of developing obesity was replicated in an independent CHS sample.

Conclusions: Children with asthma may be at higher risk of obesity. Asthma rescue medication use appeared to reduce obesity risk independent of physical activity.

Keywords: asthma, obesity, children, medication, longitudinal

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Asthma and obesity often occur together in children. Numerous studies have shown increased risk of asthma and more severe respiratory symptoms among overweight or obese children and adults.

What This Study Adds to the Field

It is unclear whether children with asthma are at higher risk for the development of obesity. This prospective study adds novel findings that children with asthma may be at higher risk of obesity. Additionally, asthma rescue medication use appeared to reduce obesity risk.

The prevalence of obesity and asthma among both children and adults has increased dramatically over the past several decades (1). A large body of evidence has documented the co-occurrence of asthma and obesity, which suggests that the pathobiology of these common conditions may be related (2). Several mechanisms have been proposed that link obesity and asthma, including obesity-influenced lung physiology, such as reductions in pulmonary compliance and limitations in airflow, systemic inflammation, dysfunctions of the sympathetic nervous system, and common genetic factors (3).

Numerous studies have shown increased risk of asthma and more severe respiratory symptoms among overweight or obese children (4, 5) and adults (6, 7). Although longitudinal studies have documented obesity as a risk factor for asthma incidence (8–11), it is unclear whether children with asthma are at higher risk for the development of obesity. Several risk factors for obesity are more prevalent among children with asthma, including reduced physical activity (12) and potential adverse effects from corticosteroid medications (13). If asthma increases the risk for developing obesity, then a portion of the obesity epidemic in children may be related to the increased occurrence of asthma or the effects of a common etiologic factor. It follows that early interventions for children with asthma could play a role in preventing obesity and related metabolic diseases because obese children are at higher risk for adult obesity and other metabolic diseases (14–16).

In this study, we investigated the effects of asthma and related phenotypes on the development of obesity in a cohort of nonobese kindergarten and first grade children (ages 5.2–7.9 yr) who participated in the southern California Children’s Health Study (CHS). We selected children who were not obese at cohort entry and examined obesity incidence during a 10-year follow-up to assess the hypothesis that children presenting with asthma in early life were at increased risk of developing obesity during childhood and adolescence. To confirm the robustness of our findings, we performed a replication analysis in an independent cohort of CHS children who were nonobese at cohort entry and were followed from a mean age of 9.7 to 17.8 years. In addition, we assessed whether asthma medication use influenced the risk of developing obesity in the primary study cohort.

Methods

Study Design

The CHS study design has been described in detail previously (17–19). Briefly, children from eight Southern California communities were followed from kindergarten or first grade to high school graduations with an original enrollment of 3,474 subjects in Cohort E. In the primary analysis, we included 2,706 children who were nonobese at study entry. We then excluded 348 subjects with only one assessment (no follow-up data), 19 subjects with baseline age older than 8 years old, and 168 subjects who did not have complete asthma history information at study entry. The present analysis focused on 2,171 children who were recruited from schools in eight communities starting in 2002 and 2003, and were followed-up till 10 years after, up to 2012. In addition, a replication study was performed in an independent CHS study sample (Cohorts C and D combined), in which children were recruited from fourth grade in 1992 and 1994, and followed until high school graduation. From the original 3,887 children, we excluded children who were obese (n = 448), missing body mass index (BMI) data (n = 186) at cohort entry, had only one visit with BMI data (n = 471), or were missing asthma history data (n = 98) at the cohort entry. As such, 2,684 children contributed to the replication sample. The University of Southern California Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Exposure and Outcomes Assessment

At study entry, written parental informed consent and student assent were obtained for all CHS participants. Children were examined annually or bi-annually during the follow-up period. Parents completed a self-administered questionnaire on sociodemographic factors, history of respiratory illness, physical activity patterns, smoking exposures at home, and other household characteristics. Questionnaires were completed by parents from baseline to Year 5, and by children from follow-up Year 6 (ages 10–13 yr) onwards. At each study visit, asthma history was classified based on a yes/no response to the question “Has a doctor ever diagnosed this child as having asthma”? Agreement of parental report of asthma was previously assessed by reviewing a sample of medical records, and 96% agreement was observed (20). Active asthma was defined as children with lifetime asthma and wheeze during the previous year of the study visit. History of asthma medication use was assessed based on questions about any rescue, controller, and other medication use for asthma or wheezing in the last 12 months. Photographic charts of medications and inhalers were used to collect information on use of specific medications. The age of asthma onset was classified into “early” (≤4 yr of age) and “late” (older than 4 yr of age). Physical activity status was collected based on responses to questions about the number of exercise classes attended and weekly days of outdoor sports in the last 12 months. Smoking exposures at home were defined based on yes/no responses to questions: “Does anyone living in this child’s home currently smoke cigarettes, cigars or pipes on a daily basis?”; and “Did this child’s biologic mother smoke while she was pregnant with this child?” Similar parents- or self-reported questionnaires were also collected annually in the replication study sample, except the category of asthma medication use was not collected, and the physical activity status was collected based on responses to the question about the number of sports teams participated in the last 12 months.

Children enrolled in the CHS had height and weight measured by a trained technician at every study visit following a standardized protocol. These objective measures of height and weight were used to calculate BMI (kg of weight/height in m2). BMI-defined overweight and obese categories were determined using the 85th and 95th BMI percentile thresholds based on the age- and sex-specific Center for Disease Control 2000 BMI growth curves (21). An incidence case of obesity was defined as the first occurrence of obesity in a child who was not obese at the cohort entry.

Statistical Analysis

Sociodemographic, physical activity, and smoking exposures were classified into categories for descriptive analyses. Baseline history of asthma medication use was classified into no medication use, using rescue medications, using nonsteroid controller medications, and using steroid asthma medications. Subjects who developed obesity during the study follow-up were censored at the midpoint of the follow-up period between the previous visit when they were not obese and the next visit when they were first determined to be obese. Subjects who were not obese during the entire study follow-up were either censored at the end of study follow-up or when they were lost to follow-up. Cox proportional hazards models were fitted to explore univariate associations between baseline characteristics and obesity incidence during follow-up from the baseline visit to the time when subjects were censored. Cox proportional hazards models with sex-specific baseline hazards were used to analyze the association of asthma and other asthma-related respiratory health at cohort entry (wheezing and asthma medication usage) with obesity incidence during follow-up. Baseline child and home characteristics, such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, overweight status, parent’s education, household annual income, child’s health insurance coverage, physical activity status, and secondhand and in utero smoking exposure, and a fixed effect of the community of residence were included as confounders. Follow-up physical activity status and asthma medication use during follow-up were also considered in the analysis using time-dependent variables. Missing data were not imputed in the analysis. Subjects with missing covariate information were included in the analysis using the missing indicator method. Interactions between baseline asthma status and baseline characteristics were tested for by including a multiplicative interaction term in the model. Stratified analysis was conducted to explore heterogeneity in effects by sex, Hispanic ethnicity, and baseline overweight status.

For sensitivity analysis, we first investigated whether asthma and asthma-related respiratory phenotypes were associated with the risk of becoming either overweight or obese using Cox proportional hazards models, adjusted for the aforementioned confounders. In this analysis, we studied a subsample of children who had normal BMIs at baseline and used the outcome as occurrence of being overweight or obese during the follow-up. Second, we investigated whether our results were significantly influenced by children who had no history of asthma at baseline but developed asthma during the follow-up period. Third, we restricted obesity incidence as children who developed obesity and were obese at two or more study visits during the entire follow-up. This analysis was conducted to determine if our results were influenced by the recurrence of obesity. Lastly, we assessed potential biases from loss to follow-up by excluding subjects who did not complete the entire 10-year study follow-up. In addition, a replication analysis was performed in the CHS replication sample for associations between asthma and other asthma-related respiratory health at cohort entry with the risk of developing obesity during follow-up. We used a similar Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for potential confounders, including the community, age, ethnicity, annual family income, parental education levels, children’s health insurance coverage, number of teams sports attended in the previous year, overweight status, past and current secondhand smoke, and follow-up number of teams sports attended as a time-dependent variable with a sex-specific baseline hazard. All statistical tests were two-sided at a 0.05 significance level. SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used for data analysis.

Results

Characteristics of the subjects at study entry are presented in Tables 1 and 2. At entry, the mean age was 6.6 ± 0.6 years, 1,084 (49.9%) were girls, 398 (18.3%) children were overweight, and 292 (13.5%) children had diagnosed asthma. The median length of follow-up was 6.9 (interquartile range, 2.3–8.6) years, with a mean of 4.3 follow-up visits. During the follow-up, 342 (15.8%) children developed obesity.

Table 1.

Univariate Associations of Child and Home Characteristics with the Risk of Developing Obesity during a Mean Follow-Up of 7 Years among 2,171 children in the Children’s Health Study Cohort E Who Were Not Obese at Study Entry*

| Baseline Variables | N† (%) | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | |||

| 5–6 | 502 (23.1) | Ref. | |

| 6–7 | 1,070 (49.3) | 1.00 | (0.77–1.29) |

| 7–8 | 599 (27.6) | 1.05 | (0.77–1.44) |

| Sex | |||

| Girls | 1,084 (49.9) | Ref. | |

| Boys | 1,087 (50.1) | 1.69 | (1.36–2.10) |

| Overweight‡ | |||

| No | 1,773 (81.7) | Ref. | |

| Yes | 398 (18.3) | 12.24 | (9.83–15.26) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 687 (31.6) | Ref. | |

| Hispanic Whites | 1,235 (56.9) | 1.93 | (1.49–2.51) |

| Others | 249 (11.5) | 1.39 | (0.93–2.06) |

| Annual family income | |||

| Less than $50,000 | 868 (40.0) | Ref. | |

| $50,000–$99,999 | 590 (27.2) | 0.71 | (0.54–0.92) |

| $100,000 or more | 395 (18.2) | 0.47 | (0.33–0.67) |

| Parental education | |||

| Less than 12th grade | 390 (18.0) | Ref. | |

| Completed grade 12 | 386 (17.8) | 0.69 | (0.49–0.97) |

| Some college or technical school | 756 (34.8) | 0.61 | (0.46–0.82) |

| More than completed 4 yr of college | 547 (25.2) | 0.52 | (0.37–0.71) |

| Baseline asthma history | |||

| No | 1,879 (86.5) | Ref. | |

| Yes | 292 (13.5) | 1.30 | (0.98–1.72) |

| Child had health insurance | |||

| No | 214 (9.9) | Ref. | |

| Yes | 1,897 (87.4) | 0.72 | (0.52–0.99) |

| Physical activity | |||

| Weekly days of outdoor sports | |||

| 0 | 353 (16.3) | Ref. | |

| 1–2 | 469 (21.6) | 1.06 | (0.75–1.50) |

| 3–4 | 636 (29.3) | 1.06 | (0.76–1.46) |

| 5–7 | 661 (30.5) | 0.96 | (0.69–1.34) |

| Previous 1-yr no. of exercise classes§ | |||

| 0 | 1,380 (63.6) | Ref. | |

| 1 | 550 (25.3) | 0.69 | (0.53–0.90) |

| ≥2 | 119 (5.5) | 0.41 | (0.21–0.79) |

| Smoking | |||

| Exposure to secondhand smoke | |||

| No | 1,988 (91.6) | Ref. | |

| Yes | 93 (4.3) | 1.08 | (0.63–1.85) |

| Yes only when children are not present | 39 (1.8) | 0.84 | (0.35–2.00) |

| Exposure to maternal smoking in utero | |||

| No | 1,977 (91.1) | Ref. | |

| Yes | 131 (6.0) | 1.05 | (0.67–1.64) |

Children in the Children’s Health Study Cohort E (as described in Methods) were enrolled in 2002, and were followed-up from a mean age of 6.6 to 15.2 years old. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented for univariate association analysis using Cox proportional hazards models.

Total number of subjects may differ owing to missing values of different baseline variables.

Overweight children were defined as children having a body mass index in the ≥85 percentile compared with sex-specific Centers of Disease Control growth curve (21).

Exercise classes include dance, aerobics, gymnastics or tumbling, martial arts, and other self-reported exercise classes.

Table 2.

Associations between Baseline Histories of Asthma and Asthma-related Health Outcomes with the Risk of Developing Obesity during a Mean Follow-up of 7 Years among Children in the Children’s Health Study Cohort E Who Were Not Obese at Study Entry* (N = 2,171)

| Baseline Histories | N† (%) | Univariate‡ |

Covariate Adjusted§ |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | ||

| Asthma | |||||

| No | 1,879 (86.5) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 292 (13.5) | 1.30 | (0.98–1.72) | 1.51 | (1.08–2.09) |

| Ever wheeze | |||||

| No | 1,540 (70.9) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 582 (26.8) | 1.06 | (0.83–1.34) | 1.42 | (1.08–1.85) |

| Wheeze in previous 1 yr | |||||

| No | 1,876 (86.4) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Yes | 272 (12.5) | 0.97 | (0.70–1.33) | 1.22 | (0.84–1.78) |

| Age of asthma onset | |||||

| No asthma | 1,879 (86.6) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Early-onset asthma (≤4 yr) | 178 (8.2) | 1.22 | (0.85–1.75) | 1.46 | (0.95–2.23) |

| Late-onset asthma (>4 yr) | 46 (2.1) | 1.29 | (0.65–2.55) | 1.39 | (0.62–3.08) |

| Active asthma | |||||

| Have no baseline asthma history and no current wheeze | 1,750 (80.6) | Ref. | Ref. | ||

| Have no baseline asthma history but have current wheeze | 108 (5.0) | 0.56 | (0.30–1.04) | 0.91 | (0.46–1.77) |

| Have baseline asthma history but no current wheeze | 126 (5.8) | 1.22 | (0.80–1.86) | 1.42 | (0.93–2.19) |

| Have baseline asthma history and current wheeze | 164 (7.6) | 1.26 | (0.88–1.81) | 1.50 | (0.96–2.33) |

Children in the Children’s Health Study Cohort E (as described in Methods) were enrolled in 2002 and were followed-up from a mean age of 6.6 to 15.2 years old. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented for association analysis using various models.

Total number of subjects may differ owing to missing values of different variables of baseline asthma history and related phenotypes.

Univariate model used sex-specific baseline hazard.

Covariates adjusted model was adjusted for baseline characteristics, including a fixed effect of the community, age, ethnicity, annual family income, parental education levels, children’s health insurance coverage (yes/no), number of exercise classes attended in the previous year, weekly days of outdoor sports, overweight status (yes/no), secondhand smoke and maternal smoking exposure in utero, and follow-up time-dependent variables, including number of exercise classes attended, weekly days of outdoor sports, and any asthma medication use with a sex-specific baseline hazard.

Table 1 presents univariate associations of child and family characteristics at study entry with obesity incidence during the follow-up period. Baseline overweight status was the strongest predictor of the follow-up obesity incidence rate (hazard ratio [HR], 12.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 9.8–15.3). In addition, males, Hispanic white children, and children from families with lower annual income and education levels were at higher risk for obesity (all P ≤ 0.035). We also observed that children taking at least two exercise classes in the previous year had almost 60% lower risk of developing obesity than children taking no exercise classes (HR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.21–0.79). However, this association was attenuated and not statistically significant after adjusting for sex, ethnicity, family income, and education levels (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.34–1.38). Univariate analysis also showed a borderline significant association between baseline asthma history and the increased risk of developing obesity (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 0.98–1.72). No significant association was found between exposures in utero to maternal smoking or to secondhand tobacco smoke and the risk for obesity (all P > 0.41).

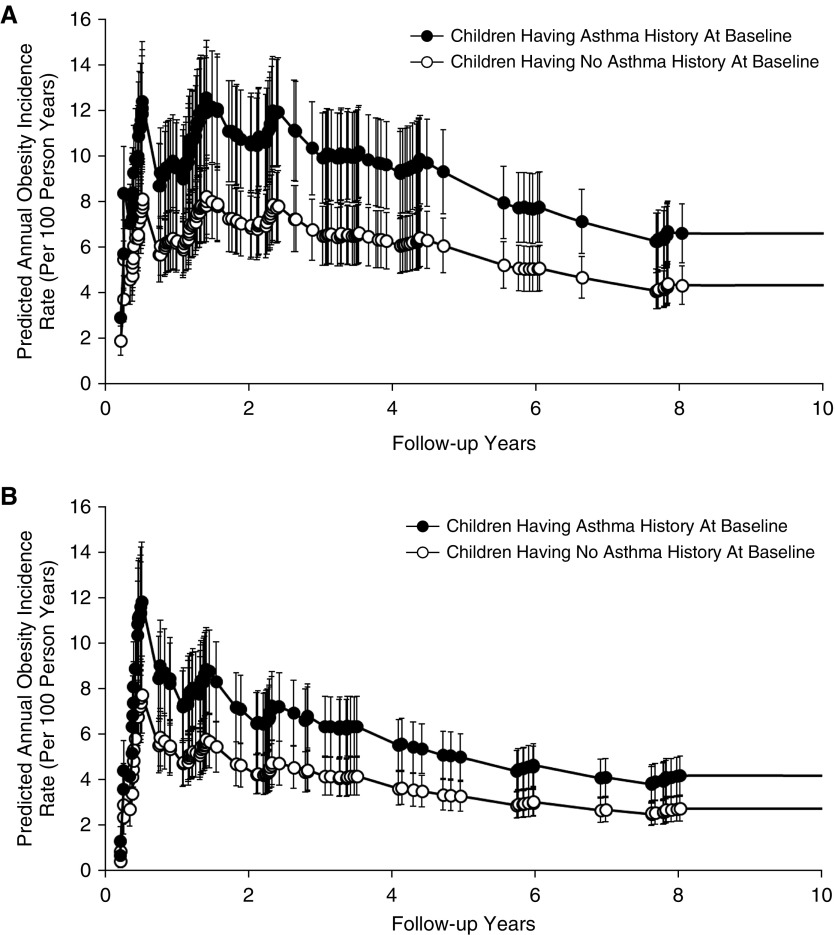

After adjusting for potential confounders, we found that early childhood asthma contributed to the development of obesity during later childhood and adolescence (Table 2). For example, the predicted annual obesity incidence rate at age 14 years was 4.2 per 100 person-years versus 2.7 per 100 person-years among girls and 6.6 per 100 person-years versus 4.3 per 100 person-years among boys comparing nonobese children who had a history of asthma at the study entry with children who had no history of asthma, respectively (Figure 1). The association result from the entire cohort suggests that nonobese children with asthma at baseline were 51% more likely to develop obesity (HR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.08–2.09) during follow-up compared with children without asthma at baseline, after adjusting for the community, age, ethnicity, annual family income, parental education levels, children’s health insurance coverage (yes/no), number of exercise classes attended in the previous year, weekly days of outdoor sports, overweight status (yes/no), exposures to secondhand smoke and maternal smoking exposure in utero, and follow-up time-dependent variables, including number of exercise classes attended, weekly days of outdoor sports, and any asthma medication use with a sex-specific baseline hazard. Children with history of wheeze before study entry were also at 42% higher risk of developing obesity (HR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.08–1.85) during follow-up compared with children who never experienced wheeze after adjusting for confounders. Age of asthma onset did not substantially affect the associated obesity risk (HR for early-onset asthma, 1.46; 95% CI, 0.95–2.23, and HR for late-onset asthma, 1.39; 95% CI, 0.62–3.08). Among children who had no history of asthma at baseline, no significant association was found between new-onset asthma during follow-up and the incidence of obesity after adjusting for confounders (HR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.52–1.55).

Figure 1.

Baseline asthma history was associated with a higher risk of developing obesity during an average of 6.8 follow-up years among (A) 1,087 boys and (B) 1,084 girls in the Children’s Health Study Cohort E (as described in Methods). The model-predicted annual obesity incidence rates and 95% confidence intervals during the entire study follow-up from a mean age of 6.6 to 15.2 years old are presented comparing children with an early-life history of asthma and children with no history of asthma at baseline among boys and girls. A Cox proportional hazards model was used to predict annual obesity incidence rates during the study follow-up, adjusting for baseline characteristics, including a fixed effect of the community, age, ethnicity, annual family income, parental education levels, children’s health insurance coverage (yes/no), number of exercise classes attended in the previous year, weekly days of outdoor sports, overweight status (yes/no), secondhand smoke and maternal smoking exposure in utero, and follow-up time-dependent variables, including number of exercise classes attended, weekly days of outdoor sports, and any asthma medication use with a sex-specific baseline hazard.

The associations of asthma phenotypes and obesity were replicated in an independent replication cohort of 2,684 children who were followed from a mean age of 9.7 to 17.8 years (baseline characteristics are shown in Table E8 in the online supplement). Baseline asthma history was significantly associated with higher obesity risk after adjusting for potential confounders (HR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.11–2.19) (Table E9).

Conditional on baseline asthma history status, children who used asthma rescue medications at study entry had a significantly reduced risk of developing obesity during the follow-up after adjusting for other controller and/or steroid asthma medication usage and potential confounders, compared with children who did not use asthma medications (Table 3) (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.33–0.96). The use of controller and steroid medications was not associated with the risk of developing obesity (all P > 0.67). We were unable to replicate these results because the independent replication cohort lacked detailed information on asthma medication use.

Table 3.

Joint Associations of Asthma and Asthma Medication Use with the Risk of Developing Obesity during a Mean Follow-up of 7 Years among Children in the Children’s Health Study Cohort E Who Were Not Obese at Study Entry* (N = 2,171)

| Baseline Histories of Asthma and Medication Use | N† (%) | Multivariate Model‡ |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | 95% CI | ||

| Baseline asthma history | |||

| No | 1,879 (86.5) | Ref. | |

| Yes | 292 (13.5) | 2.21 | (1.47–3.34) |

| Use rescue medications | |||

| No | 1,866 (86.0) | Ref. | |

| Yes | 256 (11.8) | 0.57 | (0.33–0.96) |

| Use controller medications | |||

| No | 2,008 (92.5) | Ref. | |

| Nonsteroid controller medication | 14 (0.6) | 1.34 | (0.35–4.97) |

| Inhaled corticosteroid | 100 (4.6) | 0.97 | (0.49–1.93) |

| Use additional steroid pills or liquids | |||

| No | 2,081 (95.9) | Ref. | |

| Yes | 41 (1.9) | 0.87 | (0.35–2.19) |

Children in the Children’s Health Study Cohort E (as described in Methods) were enrolled in 2002 and were followed-up from a mean age of 6.6 to 15.2 years old. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are presented for association analysis using various models.

Total number of subjects may differ owing to missing values of different baseline variables of asthma history and asthma medication use.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to jointly model obesity incidence rate as a function of baseline histories of asthma, use of rescue medications, controller medications, and additional steroid pills or liquids, adjusting for baseline characteristics including a fixed effect of the community, age, ethnicity, annual family income, parental education levels, children’s health insurance coverage (yes/no), number of exercise classes attended in the previous year, weekly days of outdoor sports, overweight status (yes/no), secondhand smoke and maternal smoking exposure in utero, and time-dependent variables, including number of exercise classes attended, and any asthma medication use during the follow-up with a sex-specific baseline hazard.

We found little evidence to support heterogeneity in the effects of asthma status on obesity based on the baseline characteristics described in Table 1 (all interaction P > 0.28; data not shown). Stratified analysis suggested that the association between baseline asthma history and follow-up obesity risk might be stronger among boys (Table E1), Hispanic whites (Table E2), and baseline overweight children (Table E3) compared with girls, non-Hispanic whites, and baseline normal weight children, respectively.

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted after adjusting for potential confounders. First, among 1,773 children who had normal weight at baseline, we investigated whether asthma and asthma-related respiratory health were associated with the risk of becoming overweight or obese (Table E4). Although the associations were not statistically significant, normal weight children with asthma at baseline tended to have higher risk of being overweight or obese during the follow-up (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.89–1.67). Second, after excluding children who had new-onset asthma during the follow-up (n = 235) and who did not have follow-up asthma information (n = 12), significant associations between asthma history at baseline and the follow-up risk of obesity remained (HR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.07–2.10) (Table E5). Third, after excluding 120 children who were obese only at one of all follow-up visits, we found a consistent association between asthma history at baseline and higher risk of obesity development during the follow-up (HR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.13–2.57) (Table E6). Lastly, there were 845 subjects who were lost to follow-up. The analysis excluding these subjects showed that the positive association between baseline asthma history and obesity risk remained significant (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.05–1.96) (Table E7).

Discussion

In this prospective study, we followed children from a mean age of 6.6 to 15.2 years and observed that children with an early-life history of asthma or wheeze by study entry were at higher risk of developing obesity. The longitudinal finding of the association between early-life history of asthma and increased risk of developing obesity during the follow-up was novel, although the association effect size of asthma on the risk of obesity was smaller than some other well-known obesity risk factors, such as baseline overweight status, low parental education levels, and Hispanic ethnicity. Children who used rescue asthma medications at study entry had a reduced risk of developing obesity. This association was independent of physical activity and other asthma medications use. Results from the independent replication cohort further supported our hypothesis that early-life history of asthma was associated with higher risk of childhood obesity among children who were followed from a mean age of 9.7 to 17.8 years. These findings were not explained by difference in age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, smoking exposures, physical activity, and overweight status at baseline.

Although most previous studies documented that obesity precedes and predicts the development of asthma (4, 8, 22), no unanimity exists. A recent prospective study following subjects from age 20 to 40 years showed that active asthma was associated with later weight gain and later obesity among women, whereas weight gain and obesity were not associated with later asthma (12). However, no association was found among men. Because children with asthma tended to be more physically inactive (23) and many asthma medications have side effects of weight gain (24), it was plausible that children with asthma were at a higher risk of developing obesity. However, there is a lack of epidemiological studies that investigate this hypothesis, especially in pediatric populations. Results from our prospective study supported the hypothesis that children with early-life asthma and wheeze are at increased risk of developing obesity during later childhood. This association was independent of physical activity, although we had limited information about daily physical activity. Interestingly, our results also suggested that using asthma rescue medication in early childhood might have had the potential to prevent development of obesity in later life. Thus, early diagnosis and treatment of asthma might avoid the vicious cycle of asthma increasing the development of obesity, with obesity subsequently causing increased asthma symptoms and morbidity leading to further weight gain. Because asthma treatments are largely efficacious, they might have the potential to help prevent obesity through early diagnosis and treatment of childhood asthma.

The biological mechanisms underlying the increased risk of obesity due to asthma are uncertain. Some studies showed that long-term treatment with glucocorticosteroids in children with asthma children can influence lipid metabolism by increasing the uptake of lipids from the digestive system and enhancing lipids storage in tissues, especially in the trunk (25). However, results of the association between asthma medication treatment and increased risk of obesity have not been consistent (26). Interestingly, our results suggested that asthma rescue medication treatment prevented obesity risk. This association was independent of physical activity and other asthma medication use. We speculate that the use of β-agonists for asthma symptoms could have direct effects on adipocytes and lipolysis, and protect against obesity (27, 28). β-2 adrenergic receptors are present in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, which mediates responses to sympathetic stimulation, and regulate fat and protein metabolism (29). Animal studies showed that β2-adrenergic stimulation increased energy expenditure and enhanced lipolysis (30, 31). In contrast, long-term use of β-blockers to inhibit the β2-adrenergic system was shown to reduce energy expenditure and fat use, and resulted in weight gain (32). A small trial further supported the beneficial effects of β2-adrenergic agonists on ameliorating obesity, in which the treatment using formoterol, a new generation of highly β2-selective agonist was shown to increase energy expenditure and fat oxidation among 12 study participants who were approximately 30 years old (33).

The strengths of this study included long-term prospective follow-up of a large cohort of children, with exposure and outcome data obtained consistently. The prospective design with nonobese children at baseline allowed us to confirm that asthma onset preceded the occurrence of obesity. In addition, our significant findings from the primary CHS study cohort were successfully replicated in an independent CHS sample from an earlier time period with a similar longitudinal study design.

There were several limitations that need to be considered in interpreting these results. First, information about asthma was self-reported in questionnaires, so misclassification could exist in our data. However, this misclassification was limited based on our previous review of medical records (20) and likely non-differential in relation to measured height and weight data, leading to bias toward the null. Second, we had limited physical activity information and no dietary information on the children in this analysis. Diet and/or physical activity had the possibility to mediate or bias our observed results between asthma and obesity incidence. Third, we used BMI and the Centers for Disease Control BMI growth curve to define overweight and obesity. Future studies using direct measures of body fat mass and distribution are needed to extend and confirm our findings. Lastly, selection bias might have existed by excluding nonobese children with incomplete data or older children at baseline as described in the study design. However, we compared characteristics among 535 excluded children with our analysis cohort, and found no significant difference between the two samples (Table E10). In addition, our sensitivity analysis, which excluded children who did not complete the study, showed that the bias caused by loss to follow-up was limited in our results.

In conclusion, children with asthma were at higher risk of developing obesity in later childhood and adolescence. Rescue medication use may reduce obesity risk independent of asthma diagnosis. In addition to excess caloric intake and lack of physical activity (34), our findings suggested that childhood asthma also contributes to the development of childhood obesity. Early interventions for children with asthma and/or wheezing may be warranted to prevent a vicious cycle of worsening obesity and asthma that could contribute to the development of other metabolic diseases, including prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in later life.

Footnotes

Supported by the Southern California Environmental Health Sciences Center grant (5P30ES007048) funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (5P01ES011627); and the Hastings Foundation.

Author Contributions: Z.C. and F.D.G. conducted the analyses and wrote the article. F.D.G. and K.B. contributed to study design and data collection. M.T.S., T.L.A., K.B., R.H., and T.M.B. edited the article and contributed to discussion. All authors reviewed the article. Z.C. and F.D.G. are the guarantors of this work, and as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201608-1691OC on January 19, 2017

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014. Health, United States, 2013: with special feature on prescription drugs. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delgado J, Barranco P, Quirce S. Obesity and asthma. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2008;18:420–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brashier B, Salvi S. Obesity and asthma: physiological perspective. J Allergy. 2013;2013:198068. doi: 10.1155/2013/198068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilliland FD, Berhane K, Islam T, McConnell R, Gauderman WJ, Gilliland SS, Avol E, Peters JM. Obesity and the risk of newly diagnosed asthma in school-age children. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:406–415. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scholtens S, Wijga AH, Seidell JC, Brunekreef B, de Jongste JC, Gehring U, Postma DS, Kerkhof M, Smit HA. Overweight and changes in weight status during childhood in relation to asthma symptoms at 8 years of age. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:1312–1318.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beckett WS, Jacobs DR, Jr, Yu X, Iribarren C, Williams OD. Asthma is associated with weight gain in females but not males, independent of physical activity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:2045–2050. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.11.2004235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nystad W, Meyer HE, Nafstad P, Tverdal A, Engeland A. Body mass index in relation to adult asthma among 135,000 Norwegian men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:969–976. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Camargo CA, Jr, Weiss ST, Zhang S, Willett WC, Speizer FE. Prospective study of body mass index, weight change, and risk of adult-onset asthma in women. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:2582–2588. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.21.2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stenius-Aarniala B, Poussa T, Kvarnström J, Grönlund EL, Ylikahri M, Mustajoki P. Immediate and long term effects of weight reduction in obese people with asthma: randomised controlled study. BMJ. 2000;320:827–832. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7238.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ford ES, Mannino DM, Redd SC, Mokdad AH, Mott JA. Body mass index and asthma incidence among USA adults. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:740–744. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00088003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spivak H, Hewitt MF, Onn A, Half EE. Weight loss and improvement of obesity-related illness in 500 U.S. patients following laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding procedure. Am J Surg. 2005;189:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasler G, Gergen PJ, Ajdacic V, Gamma A, Eich D, Rössler W, Angst J. Asthma and body weight change: a 20-year prospective community study of young adults. Int J Obes. 2006;30:1111–1118. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. The relation of childhood BMI to adult adiposity: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics. 2005;115:22–27. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li C, Ford ES, Zhao G, Mokdad AH. Prevalence of pre-diabetes and its association with clustering of cardiometabolic risk factors and hyperinsulinemia among U.S. adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2006. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:342–347. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dietz WH. Health consequences of obesity in youth: childhood predictors of adult disease. Pediatrics. 1998;101:518–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freedman DS, Mei Z, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS, Dietz WH. Cardiovascular risk factors and excess adiposity among overweight children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. J Pediatr. 2007;150:12–17.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Z, Salam MT, Eckel SP, Breton CV, Gilliland FD. Chronic effects of air pollution on respiratory health in Southern California children: findings from the Southern California Children’s Health Study. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:46–58. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.12.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gauderman WJ, Urman R, Avol E, Berhane K, McConnell R, Rappaport E, Chang R, Lurmann F, Gilliland F. Association of improved air quality with lung development in children. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:905–913. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urman R, McConnell R, Islam T, Avol EL, Lurmann FW, Vora H, Linn WS, Rappaport EB, Gilliland FD, Gauderman WJ. Associations of children’s lung function with ambient air pollution: joint effects of regional and near-roadway pollutants. Thorax. 2014;69:540–547. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-203159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salam MT, Gauderman WJ, McConnell R, Lin P-C, Gilliland FD. Transforming growth factor-1 C-509T polymorphism, oxidant stress, and early-onset childhood asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:1192–1199. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200704-561OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Wei R, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson CL. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat 11. 2002:1–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ford ES. The epidemiology of obesity and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:897–909. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.11.050. [Quiz, p. 910.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams B, Powell A, Hoskins G, Neville R. Exploring and explaining low participation in physical activity among children and young people with asthma: a review. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwarzer G, Bassler D, Mitra A, Ducharme FM, Forster J. Ketotifen alone or as additional medication for long-term control of asthma and wheeze in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(1):CD001384. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001384.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Umławska W. Adipose tissue content and distribution in children and adolescents with bronchial asthma. Respir Med. 2015;109:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crowley S, Hindmarsh PC, Matthews DR, Brook CG. Growth and the growth hormone axis in prepubertal children with asthma. J Pediatr. 1995;126:297–303. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70566-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Enoksson S, Talbot M, Rife F, Tamborlane WV, Sherwin RS, Caprio S. Impaired in vivo stimulation of lipolysis in adipose tissue by selective beta2-adrenergic agonist in obese adolescent girls. Diabetes. 2000;49:2149–2153. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.12.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macho-Azcarate T, Marti A, Gonzalez A, Martinez JA, Ibanez J. Gln27Glu polymorphism in the beta2 adrenergic receptor gene and lipid metabolism during exercise in obese women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:1434–1441. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bachman ES, Dhillon H, Zhang CY, Cinti S, Bianco AC, Kobilka BK, Lowell BB. BetaAR signaling required for diet-induced thermogenesis and obesity resistance. Science. 2002;297:843–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1073160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Björgell P, Belfrage P. Characteristics of the lipolytic beta-adrenergic receptors in hamster adipocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;713:80–85. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(82)90169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mersmann HJ. Acute metabolic effects of adrenergic agents in swine. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:E85–E95. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1987.252.1.E85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee P, Kengne AP, Greenfield JR, Day RO, Chalmers J, Ho KK. Metabolic sequelae of β-blocker therapy: weighing in on the obesity epidemic? Int J Obes. 2011;35:1395–1403. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee P, Day RO, Greenfield JR, Ho KK. Formoterol, a highly β2-selective agonist, increases energy expenditure and fat utilisation in men. Int J Obes. 2013;37:593–597. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ho M, Garnett SP, Baur LA, Burrows T, Stewart L, Neve M, Collins C. Impact of dietary and exercise interventions on weight change and metabolic outcomes in obese children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167:759–768. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]