Abstract

Rationale: Beyond the risks of smoking, there are limited data on factors associated with change in lung function over time.

Objectives: To determine whether cardiorespiratory fitness was longitudinally associated with preservation of lung health.

Methods: Prospective data were collected from 3,332 participants in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study aged 18–30 in 1985 who underwent treadmill exercise testing at baseline visit, and 2,735 participants with a second treadmill test 20 years later. The association between cardiorespiratory fitness and covariate adjusted decline in lung function was evaluated.

Measurements and Main Results: Higher baseline fitness was associated with less decline in lung function. When adjusted for age, height, race-sex group, peak lung function, and years from peak lung function, each additional minute of treadmill duration was associated with 1.00 ml/yr less decline in FEV1 (P < 0.001) and 1.55 ml/yr less decline in FVC (P < 0.001). Greater decline in fitness was associated with greater annual decline in lung function. Each 1-minute decline in treadmill duration between baseline and Year 20 was associated with 2.54 ml/yr greater decline in FEV1 (P < 0.001) and 3.27 ml/yr greater decline in FVC (P < 0.001). Both sustaining higher and achieving relatively increased levels of fitness over 20 years were associated with preservation of lung health.

Conclusions: Greater cardiopulmonary fitness in young adulthood, less decline in fitness from young adulthood to middle age, and achieving increased fitness from young adulthood to middle age are associated with less decline in lung health over time.

Clinical trial registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT 00005130).

Keywords: respiratory function tests, respiratory epidemiology, exercise, physical fitness

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Beyond the risks of smoking, there are limited data on factors associated with loss versus preservation of lung health over time. We sought to evaluate whether cardiorespiratory fitness was associated with preservation of lung function from young adulthood to middle age.

What This Study Adds to the Field

In this observational cohort study, both attainment of greater fitness and preservation of fitness over 20 years were associated with less decline in lung function from young adulthood to middle age. Findings were consistent in nonsmokers and smokers alike. Cardiorespiratory fitness may reflect a modifiable risk factor that is associated with preservation of lung health in adult life.

Lung disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality, affecting up to 15% of adults in developed nations. Lung health in adults is typically defined by the preservation of lung function after it peaks around age 25. The trajectory of decline following attainment of peak lung function is variable. Although cigarette smoking is a well-studied contributor to loss of lung function (1–3), there are limited data on factors associated with maintenance of lung health (4).

Cardiorespiratory fitness has been shown to be protective against the development of cardiovascular disease (5, 6), hypertension (7), hyperlipidemia (8), and type 2 diabetes (9, 10). Previous cross-sectional studies have suggested that regular fitness training is associated with higher pulmonary function, particularly in the context of established lung disease (11, 12).

Although some studies indicate that greater physical activity in childhood is associated with better lung function over time (13–15), there are limited longitudinal data examining the relationship between physical activity or cardiorespiratory fitness and lung function across the lifespan. A higher level of self-reported physical activity in smoking participants of the Copenhagen City Heart Study was associated with attenuation of age-related decline in lung function and lower risk of incident chronic obstructive pulmonary disease over 10–13 years (16). Self-reported physical activity, however, is inherently subject to misclassification and may result in unreliable estimation of the relationship between cardiorespiratory fitness and health outcomes.

Using longitudinal data from the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) study, a U.S.-based cohort study of young adults aged 18–30 years, we examined the relationship between objective measurements of cardiorespiratory fitness and lung health from young adulthood into middle age. We hypothesized that independent of body mass index (BMI), better fitness at baseline is associated with less decline in pulmonary function over time, and that maintaining fitness is associated with preservation of lung health from young adulthood to middle age. Some of the results of this study have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (17).

Methods

Study Design and Sample

CARDIA is a prospective cohort study of the evolution of cardiovascular disease risk factors in young adults (18). From 1985 to 1986, a total of 5,115 black and white individuals aged 18–30 years were examined in four locations (Birmingham, AL; Chicago, IL; Minneapolis, MN; and Oakland, CA). Recruitment achieved nearly equal numbers at each site of race, sex, education (more than high school or high school or less), and age (18–24 yr or 25–30 yr). Fifty percent of invited individuals contacted were examined (47% of black persons and 60% of white persons). Reexamination occurred after 2, 5, 7, 10, 15, 20, and 25 years. Cardiorespiratory fitness was measured at Years 0, 7, and 20, although variations in the Year 7 test resulting in poor reliability of the measurement preclude comparisons with the Years 0 and 20 results. Lung spirometry was performed at Years 0, 2, 5, 10, and 20. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of each center. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Measurement of Cardiorespiratory Fitness

Fitness in CARDIA was measured by symptom-limited, graded treadmill exercise testing using a modified Balke protocol (19). This consisted of nine 2-minute stages of increasing difficulty: stage 1 was 3 miles per hour at a 2% grade (4.1 metabolic equivalent task), with incremental increase in both speed and grade to a maximum of 5.6 mph at 25% grade (19.0 metabolic equivalent task). Both the test duration and maximal metabolic equivalent task attained were recorded.

Measurement of Lung Function

Lung function was measured at Years 0, 2, 5, 10, and 20. Standard spirometry procedures as recommended by the American Thoracic Society were followed at all of the examinations (20–23). Considering the young age of some participants at baseline and the possibility that lung function had not yet reached the maximum at Year 0, we estimated an individual’s peak lung function as the maximum attained at Year 0, 2, 5, 10, or 20. Four percent of participants had their highest FVC measured at the Year 20 examination. Change in lung function was calculated as estimated peak lung function minus Year 20 lung function.

Statistical Analysis

Participants were excluded if they were missing baseline fitness data, did not attend the Year 20 examination or were missing Year 20 lung function or key covariates (exclusion from analyses related to baseline fitness and future lung health), or missing the Year 20 fitness test (exclusion from analyses related to longitudinal change in fitness and lung health) (see Figure E1 in the online supplement). Because of variation in baseline fitness by sex (women on average have lower maximum level of fitness than men), we generated sex-specific quartiles of maximum treadmill duration for both baseline fitness and change in fitness from Year 0 to Year 20 (calculated as Yr 0 minus Yr 20 treadmill duration).

We also devised categorical fitness-change groups that reflect an individual participant’s fitness relative to their peers over the course of 20 years:

-

-

“Sustained high fitness”: participants with levels of fitness that were above the sex-specific median at both the Year 0 and Year 20 examinations

-

-

“Sustained low fitness”: participants with levels of fitness that were below the sex-specific median at both the Year 0 and Year 20 examinations

-

-

“Increased fitness”: participants with levels of fitness that was below the sex-specific median at the Year 0 examination but above the median at the Year 20 examination

-

-

“Decreased fitness”: participants with levels of fitness that were above the sex-specific median at Year 0 but below the median at Year 20.

Multivariable linear regression was used to determine the relationship between annualized decline in lung function (set to zero when maximal lung function was attained at Yr 20), baseline fitness, and 20-year change in fitness (evaluated as a continuous variable). Covariables in the initial models included race-sex group, center, age, height, peak lung function, and years from attainment of peak lung function to Year 20. In a second model intended to account for the potential confounding effects of obesity and cigarette smoking, BMI (baseline), change in BMI to Year 20, and lifetime pack-years smoked at Year 20 were added. For models addressing 20-year continuous change in fitness, Year 0 treadmill duration was included as a covariable.

Exploratory analyses to determine whether systemic inflammation mediates the associations between fitness and lung health were performed according to the method of Hayes and colleagues (24, 25). Mediation models were developed via the PROCESS macro in SAS (Cary, NC) (25). For models testing the association between baseline fitness and lung health, Year 7 C-reactive protein (CRP) or fibrinogen were inserted as mediators. For models testing the association between 20-year change in fitness and lung health, Year 20 CRP or fibrinogen were inserted as mediators. Estimates were made for the indirect effect of the mediator on the relationship between fitness and lung health and bootstrap 95% confidence intervals (CIs) determined through random resampling of 10,000 cases (24).

Sensitivity analyses restricting the population to only those participants who achieved 85% of their age-predicted maximum heart rate during their fitness test were performed. Because smoking is the greatest known risk factor for lung function decline and may also impact fitness through influences on health in general, analyses stratified by smoking intensity were performed with generalized linear models used to estimate covariate adjusted mean values of annual lung function decline across sex-specific quartiles of 20-year change in fitness.

For the categorical fitness-change groups, generalized linear models were used to estimate mean values for annual decline in lung function adjusted for each of the covariables described previously. Pairwise comparisons were made between these mean values using a Bonferroni-adjusted significance threshold of P equal to 0.008 to account for multiple comparisons.

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of 3,332 participants were included in the analyses evaluating the association between baseline fitness and lung health and 2,735 participants were included in the analyses of 20-year change in fitness and its association with lung health (see Figure E1). Characteristics of participants who did not complete the Year 20 fitness test compared with those who did are documented in Table E1. Participant characteristics across sex-specific quartiles of baseline (Year 0) cardiorespiratory fitness are shown in Table 1. In both men and women, African-Americans had lower fitness than white persons. Participants in the lowest fitness quartiles had higher BMI than those in the highest quartiles. Peak FEV1 and FVC were slightly lower in the lowest versus highest fitness quartiles and Year 20 FEV1 and FVC were lower in the lower baseline fitness groups. All mean lung function values were notably in the normal range.

Table 1.

Baseline Participant Characteristics by Sex-Stratified Year 0 Fitness Quartiles

| |

Quartile 1 |

Quartile 2 |

Quartile 3 |

Quartile 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Lowest Baseline Fitness → Greatest Baseline Fitness) | ||||

| Men, n | 361 | 304 | 413 | 362 |

| Range of treadmill duration (Y0), min | 2.05–10.43 | 10.47–11.98 | 12.0–13.37 | 13.38–18.00 |

| Mean treadmill duration (Y0), min | 8.88 (1.40) | 11.23 (0.40) | 12.53 (0.50) | 14.53 (1.07) |

| African American, n (%) | 204 (56.5) | 137 (45.1) | 162 (39.2) | 97 (26.8) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.8 (5.21) | 24.4 (3.24) | 23.6 (2.88) | 23.1 (2.15) |

| Age (Y0) | 25.4 (3.60) | 24.9 (3.36) | 25.2 (3.55) | 25.0 (3.47) |

| Pack-years smoking (Y0) | 2.86 (5.54) | 2.47 (4.69) | 1.98 (4.18) | 1.11 (2.97) |

| Pack-years smoking (Y20) | 7.71 (12.86) | 6.46 (10.45) | 5.32 (10.125) | 2.94 (6.98) |

| Exercise max heart rate (Y0) | 171 (18) | 183 (12) | 185 (13) | 190 (11) |

| Peak FEV1, % predicted | 98.6 (12.4) | 100.0 (11.9) | 100.9 (12.0) | 102.4 (10.6) |

| Peak FVC, % predicted | 101.7 (11.0) | 102.2 (12.1) | 104.7 (11.5) | 104.6 (11.0) |

| Peak FEV1/FVC, % | 83.2 (6.62) | 83.4 (5.76) | 82.5 (6.71) | 83.4 (5.78) |

| Year 20 FEV1, % predicted | 90.2 (15.0) | 92.8 (13.5) | 94.3 (14.5) | 97.6 (12.0) |

| Year 20 FVC, % predicted | 92.3 (13.7) | 94.9 (13.1) | 97.3 (13.1) | 99.5 (12.9) |

| Year 20 FEV1/FVC, % | 78.1 (8.0) | 78.0 (7.8) | 77.4 (7.8) | 78.0 (6.0) |

| Decline* FEV1, ml/yr, peak minus Y20 | 40.9 (25.5) | 38.9 (23.1) | 38.1 (20.2) | 35.2 (19.2) |

| Decline* FVC, ml/yr, peak minus Y20 | 44.2 (31.1) | 39.4 (25.1) | 40.1 (26.7) | 36.0 (25.3) |

| Decline* FEV1/FVC, %/yr, peak minus Y20 | 0.30 (0.32) | 0.31 (0.31) | 0.31 (0.27) | 0.31 (0.25) |

| Women, n | 434 | 518 | 433 | 507 |

| Range of treadmill duration (Y0), min | 0.18–6.98 | 7.00–8.00 | 8.02–9.98 | 10.00–18.00 |

| Mean treadmill duration (Y0), min | 5.50 (1.12) | 7.57 (0.40) | 9.00 (0.50) | 11.26 (1.31) |

| African American, n (%) | 350 (80.7) | 310 (59.9) | 183 (42.3) | 88 (17.4) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.5 (7.27) | 24.3 (4.49) | 22.7 (3.19) | 21.4 (2.18) |

| Age (Y0) | 25.4 (3.81) | 24.6 (3.86) | 25.0 (3.53) | 25.2 (3.48) |

| Pack-years smoking (Y0) | 2.32 (4.25) | 2.07 (4.31) | 1.85 (4.17) | 1.43 (3.77) |

| Pack-years smoking (Y20) | 5.87 (9.23) | 5.01 (8.77) | 4.04 (8.15) | 3.00 (7.08) |

| Exercise max heart rate (Y0) | 167 (18) | 177 (13) | 182 (11) | 184 (11) |

| Peak FEV1, % predicted | 101.4 (13.3) | 101.4 (11.4) | 104.0 (12.9) | 104.3 (11.2) |

| Peak FVC, % predicted | 104.7 (14.8) | 104.1 (11.6) | 106.6 (12.3) | 107.4 (11.2) |

| Peak FEV1/FVC, % | 86.2 (5.5) | 86.2 (5.92) | 86.1 (5.71) | 85.4 (6.33) |

| Year 20 FEV1, % predicted | 90.7 (17.8) | 93.0 (14.8) | 95.9 (13.8) | 97.3 (13.2) |

| Year 20 FVC, % predicted | 91.8 (18.6) | 94.3 (13.8) | 97.8 (13.2) | 100.1 (12.9) |

| Year 20 FEV1/FVC, % | 80.1 (7.0) | 80.1 (7.0) | 79.0 (6.0) | 78.8 (6.0) |

| Decline* FEV1, ml/yr, peak minus Y20 | 35.3 (21.5) | 32.2 (18.4) | 32.0 (17.6) | 30.9 (17.4) |

| Decline* FVC, ml/yr, peak minus Y20 | 38.5 (27.8) | 33.3 (23.3) | 32.2 (22.7) | 29.4 (21.1) |

| Decline* FEV1/FVC, %/yr, peak minus Y20 | 0.34 (0.31) | 0.36 (0.27) | 0.38 (0.27) | 0.40 (0.31) |

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; Y0 = Year 0; Y20 = Year 20.

Data are expressed as mean (SD), unless otherwise indicated.

Decline is defined as peak minus Year 20 lung function such that a positive number denotes a greater decline in lung function and a negative number denotes less decline.

Participant characteristics across sex-specific quartiles of 20-year continuous change in cardiorespiratory fitness are shown in Table E2. Among both men and women BMI was similar across quartiles of decline in fitness at Year 0; however, at Year 20 those with the greatest decline in fitness had higher BMI. Both peak FEV1 and FVC were similar across all quartiles of fitness decline. Year 20 FEV1 and FVC were lower with greater declines in fitness over 20 years. Characteristics across categorical fitness-change groups are documented in Table E3.

Baseline Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Loss of Lung Health

Associations between baseline cardiorespiratory fitness and decline in lung function are shown in Table 2. In an initial model adjusted for age, height, race-sex group, peak lung function, and years from peak lung function, baseline fitness was associated with less decline in lung function. Each additional minute of treadmill duration was associated with 1.00 ml/yr less decline in FEV1 (P < 0.001) and 1.55 ml/yr less decline in FVC (P < 0.001). These relationships remained significant after adjustment for BMI, change in BMI from Year 0 to Year 20, and lifetime pack-years cigarette smoking. When this analysis was repeated excluding participants who did not achieve 85% of their maximum heart rate during the baseline test, the results in model 1 remained significant, but in model 2 were no longer statistically significant (see Table E4).

Table 2.

Association between Baseline Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Annualized Decline in Lung Health from Peak Measurement to Year 20

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | P Value | β (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Decline* FEV1, ml/yr | −1.00 (−1.230 to −0.70) | <0.001 | −0.43 (−0.76 to −0.09) | 0.01 |

| Decline* FVC, ml/yr | −1.55 (−1.92 to −1.18) | <0.001 | −0.50 (−0.91 to −0.10) | 0.01 |

| Decline* FEV1/FVC, %/yr | 0.52 (0.00 to 0.91) | 0.03 | −0.31 (−0.72 to .23) | 0.30 |

Definition of abbreviation: CI = confidence interval.

Values shown are per minute baseline treadmill duration (a negative coefficient indicates that greater baseline fitness is associated with less decline in lung function). Model 1 covariates: age, race-sex group, height, center, peak lung function, years from peak lung function to Year 20. Model 2 covariates: model 1 + body mass index (Yr 0), change in body mass index (Yr 0 to Yr 20), lifetime pack-years smoked (Yr 20).

Decline is defined as peak minus Year 20 lung function such that a positive number denotes a greater decline in lung function and a negative number denotes less decline.

To explore whether systemic inflammation in young adulthood mediates the association between baseline fitness and loss of lung health, we determined the indirect effects of Year 7 CRP and fibrinogen on the observed associations in the fully adjusted model. There were significant indirect effects of baseline fitness on FEV1 decline through Year 7 CRP (indirect effect, −0.045; 95% CI, −0.091 to −0.016; 8% of the total effect) and fibrinogen (indirect effect, −0.045; 95% CI, −0.094 to −0.016; 8% of the total effect). Similarly, there were significant indirect effects of baseline fitness on FVC decline through Year 7 CRP (indirect effect, −0.046; 95% CI, −0.105 to −0.013; 7% of the total effect) and fibrinogen (indirect effect, −0.054; 95% CI, −0.114 to −0.018; 9% of the total effect).

Twenty-year Change in Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Loss of Lung Health

Associations between 20-year continuous change in fitness and decline in lung function are shown in Table 3. Greater decline in fitness was associated with greater decline in both FEV1 and FVC. In the initial model adjusted for age, race-sex group, height, center, baseline treadmill duration, peak lung function, and years from peak lung function to Year 20, each 1-minute decline in treadmill duration between baseline and 20 years was associated with 2.54 ml/yr greater decline in FEV1 (P < 0.001) and 3.25 ml/yr greater decline in FVC (P < 0.001). Both findings remained significant after adjustment for BMI, change in BMI, and lifetime pack-years smoking. These findings were similar in a sensitivity analysis restricted to only participants who achieved 85% of the age-predicted maximum heart rate at both the baseline and Year 20 treadmill tests (see Table E5).

Table 3.

Association between Continuous Decline in Cardiorespiratory Fitness (Yr 0 To Yr 20) and Annualized Decline in Lung Health from Peak Measurement to Year 20

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | P Value | β (95% CI) | P Value | |

| Decline* FEV1, ml/yr | 2.54 (2.18 to 2.90) | <0.001 | 1.95 (1.54 to 2.36) | <0.001 |

| Decline* FVC, ml/yr | 3.27 (2.82 to 3.72) | <0.001 | 2.08 (1.56 to 2.58) | <0.001 |

| Decline* FEV1/FVC, %/yr | 0.12 (−0.51 to 0.60) | 0.78 | 1.0 (0.42 to 1.6) | 0.002 |

Definition of abbreviation: CI = confidence interval.

Values shown are per minute decline in treadmill duration between Year 0 and Year 20 (a positive coefficient indicates that greater decline in fitness is associated with greater decline in lung function). Model 1 covariates: age, race-sex group, height, center, peak lung function, Year 0 treadmill duration, years from peak lung function to Year 20. Model 2 covariates: model 1 + body mass index (Yr 0), change in body mass index (Yr 0 to Yr 20), lifetime pack-years smoked (Yr 20).

Decline is defined as peak minus Year 20 lung function such that a positive number denotes a greater decline in lung function and a negative number denotes less decline.

To determine whether systemic inflammation mediates the association between change in fitness and lung health, we determined the indirect effects of Year 20 CRP and fibrinogen on the observed associations. There were significant indirect effects of fitness change on FEV1 decline through Year 20 CRP (indirect effect, 0.247; 95% CI, 0.131–0.434; 13% of the total effect) and fibrinogen (indirect effect, 0.078; 95% CI, 0.029–0.161; 4% of the total effect). Similarly, there were significant indirect effects of fitness change on FVC decline through Year 20 CRP (indirect effect, 0.238; 95% CI, 0.111–0.420; 11% of the total effect) and fibrinogen (indirect effect, 0.121; 95% CI, 0.050–0.234; 6% of the total effect).

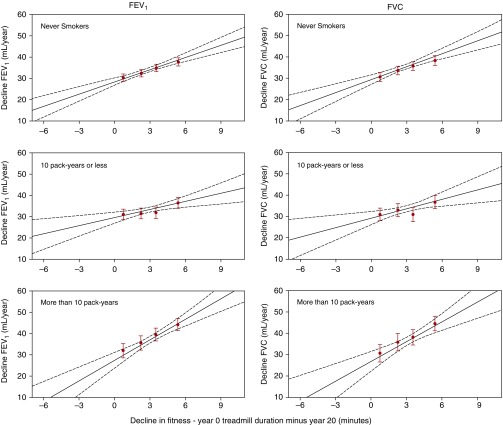

Adjusted mean values of decline in lung function stratified by lifetime smoking intensity are shown in Figure 1. The relationship between change in fitness and decline in lung health was significant in never smokers, 10 pack-year or less smokers, and more than 10 pack-year smokers alike.

Figure 1.

Mean adjusted decline in lung health (FEV1 and FVC) from peak measurement to Year 20 across sex-specific quartiles of 20-year change in cardiorespiratory fitness stratified by lifetime smoking intensity. Red dots represent mean (with standard error of the mean) decline in lung function for each sex-specific quartile of decline in fitness, and multivariable linear regression lines are superimposed as solid lines with 95% confidence intervals represented as dashed lines. (never smokers, n = 1,585; ≤10 pack-years, n = 685; ≥10 pack-years, n = 465) (FEV1: never smokers, β = 1.91, P < 0.001; ≤10 pack-years, β = 1.27, P = 0.002; ≥10 pack-years, β = 3.17, P < 0.001) (FVC: never smokers, β = 2.04, P < 0.001; ≤10 pack-years, β = 1.47, P = 0.003; ≥10 pack-years, β = 3.15, P < 0.001). All β coefficients are in units of ml/yr decline in FEV1 or FVC per minute decline in treadmill performance such that a higher positive number denotes greater decline in lung function.

Mean adjusted values for decline in lung function across the categorical fitness-change groups are shown in Table 4. Both sustained high and increased fitness were associated with less decline in the FEV1 and FVC when compared with sustained low and decreased fitness. These findings remained similar when restricting the population to those achieving 85% of their age-predicted heart rate during both the baseline and Year 20 fitness tests (see Table E6).

Table 4.

Mean (SE) Adjusted Annualized Decline in Lung Function from Peak Measurement to Year 20 across Categorical Fitness Change Groupings

| Sustained High Fitness | Increased Fitness | Decreased Fitness | Sustained Low Fitness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEV1, ml/yr | 31.1*† (0.62) | 31.6*† (0.99) | 36.9 (0.83) | 36.7 (0.62) |

| FVC, ml/yr | 31.2*† (0.75) | 31.5*† (1.19) | 37.8 (1.01) | 37.3 (0.76) |

| FEV1/FVC, %/yr | 0.33 (0.009) | 0.33 (0.015) | 0.35 (0.012) | 0.35 (0.009) |

Values adjusted for age, race-sex group, height, center, peak lung function, years from peak lung function to Year 20, body mass index (Yr 0), change in body mass index (Yr 0 to Yr 20), lifetime pack-years smoked (Yr 20).

P < 0.001 versus sustained lower fitness group.

P < 0.001 versus decreased fitness group.

Discussion

In the CARDIA study of young adults aged 18–30 years old at baseline, we found that participants who had the greatest preservation of cardiorespiratory fitness over 20 years had the least decline in lung health. Even among cigarette smokers, who are at the highest risk for loss of lung function and future lung disease, preservation of fitness over 20 years was associated with less decline in lung function. Furthermore, participants achieving increased fitness over the same period had better preservation of lung health. This novel finding suggests that consideration should be given as to whether lung function decline in adult life may be modified through improvements in cardiorespiratory fitness.

Strengths of our study include analysis of a large, biracial cohort of healthy young adults allowing for the study of lung health immediately following attainment of peak lung function. Repeated measures of both the symptom-limited exercise test and lung function allow for a longitudinal assessment of the relationship between fitness and lung health focused on a healthy population rather than prior reports of disease. Finally, the robust data collection in CARDIA allows us to adjust for the most likely confounders of the associations we report, including obesity and cigarette smoking.

One could argue that it is the decline in lung function that results in greater decline in fitness and not vice versa. Proving a causal association in either direction is not possible in this observational study, but we think this is unlikely. Even in participants in the highest quartile of decline in fitness, mean lung function at Year 20 was still in the normal range. In healthy people with normal lung function, like most participants in CARDIA, the respiratory system does not limit high-intensity endurance exercise (26, 27). Furthermore, in our sensitivity analyses restricted to participants who achieved 85% of their age-predicted maximum heart rate, indicating that they were not limited in performance by respiratory abnormalities, all of the associations were preserved.

We define lung health in terms of decline in lung function from an estimated peak measurement in young adulthood, which may represent an oversimplification of the respiratory system. Although we report relatively small differences in lung function decline, when viewed through the lens of public health, strategies that mitigate age-related decline in lung function (something that is not typically viewed as modifiable) even in a small fashion could have a meaningful impact on the frequency of lung disease (4). We are limited by the fact that we only have measurements of fitness at two time-points separated by 20 years and fitness in an individual could vary over time, and we therefore cannot account for how more incremental variations in fitness impact lung health. In addition, a significant proportion of participants who attended the Year 20 examination did not perform a fitness test. This is unlikely to occur at random: those with the lowest levels of fitness might decline testing. A comparison of those who completed the fitness test with those who declined indicates that those who declined did indeed have the greatest decline in lung function. These missing data, therefore, would bias our results toward the null rather than introduce concerns regarding the validity of our results.

The association between cardiorespiratory fitness and long-term health outcomes, particularly in the realm of cardiovascular disease, has been well documented (28). In a pooled analysis of 33 observational studies, mostly among older adults, better cardiorespiratory fitness was associated with lower risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality (6). In CARDIA, higher levels of baseline fitness were associated with lower hazard of death and cardiovascular events (8, 29). In addition, greater baseline fitness was associated with lower left ventricular mass and strain pointing to favorable effects of fitness on myocardial structure and function (29). We have previously described an association between loss of lung health and increased left ventricular mass illustrating the links between cardiovascular and lung health (30), but how fitness, particularly from early adulthood to middle age, intersects with lung health has not been well-evaluated. Based on this prior work, one notable aspect of our findings is that greater fitness in young adults may be associated with protection from a heart-lung phenotype of accelerated decline in lung function and increased left ventricular mass. This shared association between fitness and both lung function decline and cardiac structure and function magnifies the potential benefits of fitness on various aspects of long-term health.

There are several possible mechanisms for why better or increased fitness is associated with better lung health including an overall improvement in conditioning of the respiratory muscles, a favorable change in chest wall mechanics among those who participate in regular exercise, changes in fat distribution not captured by BMI, favorable changes in lung or airway perfusion that result in improved pulmonary function, or a reduction in the overall systemic inflammatory state among those who are fit. Based on our prior work that documented an association between systemic inflammation and decline in lung health (31) and the fact that fitness is associated with less systemic inflammation (32, 33), we explored the possible mediating effects of systemic inflammation on the associations between fitness and lung health. We documented significant indirect effects of both CRP and fibrinogen in our analyses pointing to reduced systemic inflammation as one clearly plausible mechanism for the favorable associations between fitness and lung health.

Reduced lung function is associated with adverse health consequences, lending credence to the concept of lung health being defined by preservation of lung function. Reduction in the FVC and FEV1 even when small in magnitude such that both measures remain in the “normal” range, have documented associations with both cardiovascular disease and death (34–38). In addition to the association between loss of lung health and high-output, hypertrophic cardiovascular phenotype described previously (30), we have also documented an association between decline in lung function from peak and incident hypertension in CARDIA (39). Our present finding that cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with preservation of lung health and that less decline in fitness over 20 years is associated with less decline in lung function (even in high-intensity smokers), raises the possibility that lung health in adult life may be modifiable by achieving and/or sustaining higher levels of cardiorespiratory fitness. Given the many adverse outcomes associated with declining lung function this finding carries clear implications for health in general.

Conclusions

In a large study of generally healthy young adults, we found an association between baseline fitness and lung health from young adulthood to middle age. Furthermore, we demonstrate an association between sustained higher levels of fitness over 20 years and preservation of lung health. Evaluating fitness in young adulthood may provide prognostic information regarding lung health over time, and sustaining or increasing fitness throughout young adulthood may have the additional benefit of improving long-term respiratory health.

Footnotes

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study is conducted and supported by the NHLBI in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham (HHSN268201300025C and HHSN268201300026C), Northwestern University (HHSN268201300027C), University of Minnesota (HHSN268201300028C), Kaiser Foundation Research Institute (HHSN268201300029C), and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (HHSN268200900041C). CARDIA is also partially supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and an intraagency agreement between NIA and NHLBI (AG0005). This manuscript has been reviewed by CARDIA for scientific content. Additional funding was provided by NHLBI R01 HL122477 (CARDIA Lung Study) and R01 HL078972 (CARDIA Fitness Study).

Author Contributions: L.R.B. conceived the study, analyzed the data, and drafted the paper. M.J.C. conceived the study, interpreted data, and drafted and revised the paper. L.A.C. performed statistical analysis and revised the paper. S.S. collected the data, interpreted data, and revised the paper. M.T.D. interpreted data and revised the paper. D.M.M. interpreted data and revised the paper. D.R.J. collected the data, interpreted data, and revised the paper. C.E.L. collected the data, interpreted the data, and revised the paper. N.Z. interpreted data and revised the paper. G.R.W. interpreted data and revised the paper. K.L. collected the data, performed analysis, interpreted the data, and revised the paper. M.R.C. conceived the study and revised the paper. R.K. conceived the study, analyzed the data, and drafted and revised the paper.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201610-2089OC on March 1, 2017

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Urrutia I, Capelastegui A, Quintana JM, Muñiozguren N, Basagana X, Sunyer J Spanish Group of the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS-I) Smoking habit, respiratory symptoms and lung function in young adults. Eur J Public Health. 2005;15:160–165. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tager IB, Segal MR, Speizer FE, Weiss ST. The natural history of forced expiratory volumes: effect of cigarette smoking and respiratory symptoms. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1988;138:837–849. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/138.4.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camilli AE, Burrows B, Knudson RJ, Lyle SK, Lebowitz MD. Longitudinal changes in forced expiratory volume in one second in adults: effects of smoking and smoking cessation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:794–799. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.4.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camargo CA, Jr, Budinger GR, Escobar GJ, Hansel NN, Hanson CK, Huffnagle GB, Buist AS. Promotion of lung health: NHLBI Workshop on the Primary Prevention of Chronic Lung Diseases. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:S125–S138. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201312-451LD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blair SN, Kampert JB, Kohl HW, III, Barlow CE, Macera CA, Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Gibbons LW. Influences of cardiorespiratory fitness and other precursors on cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in men and women. JAMA. 1996;276:205–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kodama S, Saito K, Tanaka S, Maki M, Yachi Y, Asumi M, Sugawara A, Totsuka K, Shimano H, Ohashi Y, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301:2024–2035. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jae SY, Heffernan KS, Yoon ES, Park SH, Carnethon MR, Fernhall B, Choi YH, Park WH. Temporal changes in cardiorespiratory fitness and the incidence of hypertension in initially normotensive subjects. Am J Hum Biol. 2012;24:763–767. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carnethon MR, Gidding SS, Nehgme R, Sidney S, Jacobs DR, Jr, Liu K. Cardiorespiratory fitness in young adulthood and the development of cardiovascular disease risk factors. JAMA. 2003;290:3092–3100. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.23.3092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carnethon MR, Sternfeld B, Schreiner PJ, Jacobs DR, Jr, Lewis CE, Liu K, Sidney S. Association of 20-year changes in cardiorespiratory fitness with incident type 2 diabetes: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) fitness study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1284–1288. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juraschek SP, Blaha MJ, Blumenthal RS, Brawner C, Qureshi W, Keteyian SJ, Schairer J, Ehrman JK, Al-Mallah MH. Cardiorespiratory fitness and incident diabetes: the FIT (Henry Ford ExercIse Testing) project. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1075–1081. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucas SR, Platts-Mills TA. Physical activity and exercise in asthma: relevance to etiology and treatment. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:928–934. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wijkstra PJ, TenVergert EM, van der Mark TW, Postma DS, Van Altena R, Kraan J, Koëter GH. Relation of lung function, maximal inspiratory pressure, dyspnoea, and quality of life with exercise capacity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1994;49:468–472. doi: 10.1136/thx.49.5.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berntsen S, Wisløff T, Nafstad P, Nystad W. Lung function increases with increasing level of physical activity in school children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2008;20:402–410. doi: 10.1123/pes.20.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menezes AM, Wehrmeister FC, Muniz LC, Perez-Padilla R, Noal RB, Silva MC, Gonçalves H, Hallal PC. Physical activity and lung function in adolescents: the 1993 Pelotas (Brazil) birth cohort study. J Adolesc Health. 2012;51(Suppl 6):S27–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Twisk JW, Staal BJ, Brinkman MN, Kemper HC, van Mechelen W. Tracking of lung function parameters and the longitudinal relationship with lifestyle. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:627–634. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12030627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Aymerich J, Lange P, Benet M, Schnohr P, Antó JM. Regular physical activity modifies smoking-related lung function decline and reduces risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population-based cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:458–463. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-896OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benck L, Cuttica M, Colangelo L, Sidney S, Dransfield MT, Lewis CE, Jacobs DR, Zhu N, Mannino D, Carnethon M, et al. Sustained or relative increases in cardiopulmonary fitness are associated with preserved lung health from young adulthood to middle age [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:A4281. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, Hughes GH, Hulley SB, Jacobs DR, Jr, Liu K, Savage PJ. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:1105–1116. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sidney S, Haskell WL, Crow R, Sternfeld B, Oberman A, Armstrong MA, Cutter GR, Jacobs DR, Savage PJ, Van Horn L. Symptom-limited graded treadmill exercise testing in young adults in the CARDIA study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;24:177–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ATS statement. Snowbird workshop on standardization of spirometry. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;119:831–838. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1979.119.5.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Statement of the American Thoracic Society. Standardization of spirometry: 1987 update. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136:1285–1298. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.5.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Thoracic Society. Lung function testing: selection of reference values and interpretative strategies. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:1202–1218. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.5.1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Thoracic Society. Standardization of spirometry, 1994 update. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1107–1136. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayes AF, Rockwood NJ. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav Res Ther. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001. [online ahead of print] 5 Nov 2016; DOI: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dempsey JA, Wagner PD. Exercise-induced arterial hypoxemia. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1999;87:1997–2006. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.6.1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aaron EA, Seow KC, Johnson BD, Dempsey JA. Oxygen cost of exercise hyperpnea: implications for performance. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1992;72:1818–1825. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.5.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blair SN, Kohl HW, III, Paffenbarger RS, Jr, Clark DG, Cooper KH, Gibbons LW. Physical fitness and all-cause mortality: a prospective study of healthy men and women. JAMA. 1989;262:2395–2401. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.17.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shah RV, Murthy VL, Colangelo LA, Reis J, Venkatesh BA, Sharma R, Abbasi SA, Goff DC, Jr, Carr JJ, Rana JS, et al. Association of fitness in young adulthood with survival and cardiovascular risk: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:87–95. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.6309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cuttica MJ, Colangelo LA, Shah SJ, Lima J, Kishi S, Arynchyn A, Jacobs DR, Jr, Thyagarajan B, Liu K, Lloyd-Jones D, et al. Loss of lung health from young adulthood and cardiac phenotypes in middle age. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:76–85. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201501-0116OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalhan R, Tran BT, Colangelo LA, Rosenberg SR, Liu K, Thyagarajan B, Jacobs DR, Jr, Smith LJ. Systemic inflammation in young adults is associated with abnormal lung function in middle age. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11431. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Church TS, Barlow CE, Earnest CP, Kampert JB, Priest EL, Blair SN. Associations between cardiorespiratory fitness and C-reactive protein in men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1869–1876. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000036611.77940.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LaMonte MJ, Durstine JL, Yanowitz FG, Lim T, DuBose KD, Davis P, Ainsworth BE. Cardiorespiratory fitness and C-reactive protein among a tri-ethnic sample of women. Circulation. 2002;106:403–406. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000025425.20606.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higgins MW, Keller JB. Predictors of mortality in the adult population of Tecumseh. Arch Environ Health. 1970;21:418–424. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1970.10667260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hole DJ, Watt GCM, Davey-Smith G, Hart CL, Gillis CR, Hawthorne VM. Impaired lung function and mortality risk in men and women: findings from the Renfrew and Paisley prospective population study. BMJ. 1996;313:711–715, discussion 715–716. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7059.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lange P, Nyboe J, Jensen G, Schnohr P, Appleyard M. Ventilatory function impairment and risk of cardiovascular death and of fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction. Eur Respir J. 1991;4:1080–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schünemann HJ, Dorn J, Grant BJ, Winkelstein W, Jr, Trevisan M. Pulmonary function is a long-term predictor of mortality in the general population: 29-year follow-up of the Buffalo Health Study. Chest. 2000;118:656–664. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.3.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sin DD, Man SFP. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:8–11. doi: 10.1513/pats.200404-032MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacobs DR, Jr, Yatsuya H, Hearst MO, Thyagarajan B, Kalhan R, Rosenberg S, Smith LJ, Barr RG, Duprez DA. Rate of decline of forced vital capacity predicts future arterial hypertension: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Hypertension. 2012;59:219–225. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.184101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]