Abstract

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy (CIPN) is a dose-limiting toxicity of several chemotherapeutics used in the treatment of all the most common malignancies. There are several defined mechanisms of nerve damage that take place along different areas of the peripheral and the central nervous system. Treatment is based on symptom management and there are several classes of medications found to be efficacious in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Neuropathic pain that persists despite appropriate pharmacotherapy may respond to interventional procedures that span a range of invasiveness. The purpose of this review article is to examine the basic science of neuropathy and currently available treatment options in the context of chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy.

Keywords: Anticonvulsants, Antidepressants, Chemotherapy toxicity, Opioids, Pain, Peripheral neuropathy

Introduction

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy is the most common neurologic complication of cancer treatment, particularly with the use of platinum-derived agents, taxanes, vinca alkaloids and proteasome inhibitors which are first-line agents in the treatment of solid tumors [1]. Chemotherapy regimens that utilize combination therapy may potentiate the sequela of neuropathy through agents that produce nerve damage via different mechanisms of action. Initial presentation begins with decreased vibration sense in the toes and loss of the ankle jerk reflex. Further, neuropathy may present as sensory deficits, loss of motor function and pain due to damage that occurs at multiple locations along the peripheral and central nervous system. It is estimated that up to 90% of all cancer patients treated with chemotherapy will be affected by chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy [2]. By example, the development of neuropathy is the most common reason for altering a platinum-based chemotherapy regimen, either by decreasing dose and frequency or by selecting a different therapeutic agent [3]. Depending on the chemotherapy regimen, chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy may self-resolve in weeks or persist for years (see Table 1.) [4–6].

Table 1.

Commonly used CIPN-inducing chemotherapy agents [19].

| Classification | Agent | Type of nerve damage |

|---|---|---|

| Platinum-based compounds | Cisplatin | Sensory |

| Carboplatin | ||

| Oxaliplatin | ||

| Vinca alkaloids | Vincristine | Sensory and motor |

| Vindesine | ||

| Vinblastine | ||

| Vinorelbine | ||

| Taxanes | Paclitaxel | Sensory and motor |

| Docetaxel | ||

| Proteasome inhibitors | Bortezomib | Sensory |

Studies on the pathophysiology of chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy suggest anatomical and/or functional changes of intraepidermal nerve fibers, primary sensory neurons, CNS neurons, and involvement of glial and immune cells. Currently there is no method of preventing chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Treatment is focused mainly on the management of the clinical symptom of neuropathic pain. Our aim is to review what is known about the basic science of neuropathy and also about the currently available treatment options. In doing so, we will focus on chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy.

Etiology and pathology of neuropathy

The incidence of peripheral neuropathy during and after the treatment of malignancies is not well-defined, although peripheral neuropathy is known to be a primary dose-limiting toxicity. Among women with ovarian cancer, up to 51% may experience peripheral neuropathy after chemotherapy manifesting especially as numbness and tingling in the hands and feet [7]. In the study of the addition of paclitaxel to cisplatin and doxorubicin for the treatment of advanced endometrial cancer, out of a total of 1203 patients 46.5% reported some form of peripheral neuropathy and 13.2% reported a CTCAE grade 2 neuropathy, with moderate symptoms limiting instrumental activities of daily living [8].

Given the widespread use of common neurotoxic chemotherapeutic agents in the treatment of different malignancies, there is a high risk of peripheral neuropathy developing as an adverse effect. Ovarian cancer is treated with a platinum-based agent such as carboplatin and may be combined with a taxane. High risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia may require combination therapy including vincristine or cisplatin. Cisplatin and paclitaxel are also used in the treatment of cervical cancer [9]. While bevacizumab alone has not been shown to cause sensory neuropathy, product information supplied by the manufacturer notes a possible increase in the rate of sensory neuropathy when used in combination with paclitaxel. In addition to systemic therapy, radiation therapy and surgery may be indicated for the treatment of gynecologic malignancies.

Nerve injury can occur via several mechanisms during the course of treatment for cancer, and bears consideration in patients who undergo multimodal therapy. Solid tumors may cause local nerve compression depending on size and location. Worsening neuropathy in the territory of a tumor may indicate progression of disease. Surgical resection and lymph node dissection can cause immediate nerve injury due to the placement of surgical tools for retraction and stretching of tissues or delayed injury through the development of postsurgical adhesions. This may present as a non-specific visceral pain. Radiation therapy in high doses causes damage to surrounding structures which may include tumor adjacent nerves and plexuses, such as the lumbosacral plexus during irradiation of pelvic organs.

Pathophysiology

Due to the important role peripheral neuropathy plays in determining the course of cancer treatment, significant research has gone into understanding the mechanisms of nerve injury after exposure to different chemotherapeutic agents. Basic science research has demonstrated chemotherapy-induced nerve damage both at the level of the peripheral and the central nervous system. The multiple areas susceptible to injury underscore the propensity towards peripheral neuropathy during the use of platinum-derived agents, taxanes, vinca alkaloids and proteasome inhibitors.

Peripheral nervous system

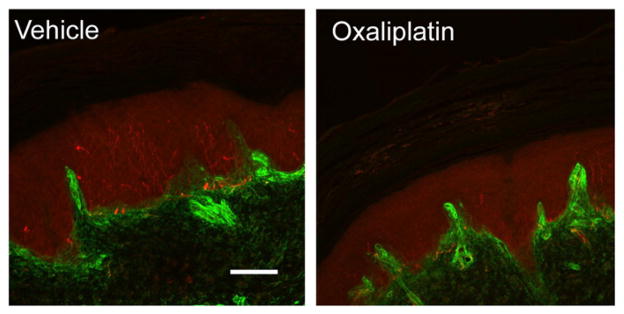

Intraepidermal nerve fiber density has been found to be reduced in patients with painful sensory neuropathies, with decreased density correlating to clinical estimates of severity of pain [10,11]. Patients with small-fiber sensory neuropathies may have fewer objective abnormalities on clinical examination and electrodiagnostic studies [12]. In the rat model, taxanes, vinca alkaloids, and platinum-based agents were found to decrease the number of intraepidermal nerve fibers of the hind paw Fig. 1 [13,14].

Fig. 1.

Oxaliplatin induces loss of intraepidermal nerve endings (IENFs) of glabrous skin. Skin tissues were taken from rats treated with vehicle or oxaliplatin 15 days after the treatment. IENFs are labeled by PGP9.5 (red) and the basement membrane is labeled by collagen IV (green). Oxaliplatin-treated tissues demonstrate decreased IENF density.

Penetration of chemotherapeutic agents into the central nervous system is relatively poor, whereas high levels have been found to accumulate within the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and peripheral nerves [15]. Activation of innate immunity in the DRG as a consequence of chemotherapy treatment appears to be a key early event in the initiation of CIPN [16,17].

The DRG of peripheral nerves are susceptible to disruption at many points, including sodium, calcium, and potassium ion channels, glutamate-activated N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, and mitochondria. The expression of numerous ion channels in DRG neurons are altered following chemotherapy treatment [18]. Activation of ion channels triggers changes in intracellular calcium that leads to the release of free radicals that subsequently induce neuropathic pain. Mitochondrial damage also increases permeability to and release of intracellular calcium, which causes activation of protein kinase C, phosphorylation of transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV), activation of capases and calpains, and the release of nitric oxide and free radicals. The end result is cytotoxic to axons and neuronal cell bodies [19].

The alpha-2-delta-1 subunits of calcium channels of the DRG and dorsal horn are upregulated by paclitaxel and vincristine. Increased cytosolic calcium is present due to the release from extracellular and intracellular stores of mitochondria [20–22]. Paclitaxel, vincristine and oxaliplatin increase the Na+ current in the DRG which accounts for the paresthesias and fasciculations associated with neuropathy [23–25]. There is decreased expression of mechanogated and temperature-sensitive potassium channels (TREK 1, TRAAK types) in the presence of oxaliplatin and increased expression of pro-excitatory channels such as the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channels [26].

At the mitochondrial level, paclitaxel, vincristine, cisplatin, and bortezomib cause swelling and vacuolization within the peripheral nerve axon, which increases permeability to and leakage of intracellular calcium. This in turn activates a caspase-mediated apoptotic pathway, leading to neuronal cell death [27–29]. By increasing cytosolic calcium, oxaliplatin, paclitaxel, vincristine, and bortezomib also increase free radicals in DRG cells [30–32]. Neuronal apoptosis is also initiated by the activation of calcium-dependent proteases, calpains and caspases in DRG cells in the presence of paclitaxel, vincristine, and oxaliplatin [33,34].

The transient receptor potential vanilloids (TRPVs) act as transducers of thermal and chemical stimuli in pain-sensing neurons. Cisplatin, oxaliplatin, and paclitaxel upregulate TRPV1 and transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channels of the subgroups TRPA1 (transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily A, member 1), TRPM8 (transient receptor potential cation channel, subfamily M (menthol), member 8) and TRPV4 in the DRG neurons causing nociceptor hyperexcitability [35–37]. Substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) are neurotransmitters that relay pain signals and these are increased in DRG neurons by paclitaxel and cisplatin [38,39]. Vincristine increases the 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptors of 5-hydroxytryptamine on the DRG neurons and dorsal horn of the spinal cord thereby sensitizing spinal dorsal horn neurons and peripheral nociceptive fibers [40,41].

The platinum-based chemotherapy agents (oxaliplatin, cisplatin, carboplatin) bind to DNA strands thereby inducing apoptotic cell death, particularly within the cell bodies of the DRG. Oxaliplatin leads to chronic neuropathy by damaging DNA and by altering the function of voltage-gated sodium channels in the peripheral nerves [42,43]. Of the platinum agents, carboplatin is the least likely to produce significant neuropathy [44]. Cisplatin has been found to accumulate in the DRG and peripheral nerves [15,45].

Paclitaxel activates macrophages and microglia in the DRG, peripheral nerves and spinal cord. In addition it has been found to stabilize microtubules and decrease epidermal nerve fiber density. With large cumulative doses, paclitaxel can also affect motor nerves [46,47].

Central nervous system

Studies have demonstrated changes within the central nervous system contributing to the development of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy. Within the spinal dorsal horn, exposure to paclitaxel, vincristine, and cisplatin is associated with a higher incidence of spontaneous activities in wide-dynamic-range neurons, enhanced evoked responses to acute natural stimuli and increased after-discharges and windup [48]. Paclitaxel decreases expression of glutamate transporter proteins and increases after-discharge and abnormal windup to transcutaneous electrical stimuli. Spontaneous activity and after-discharge to noxious mechanical thermal stimuli of the skin occurs within deep spinal lamina neurons [48]. Vincristine enhances NMDA receptor expression and diminishes CGRP expression, leading to a state of glutamate excitotoxicity that results in axonal degeneration. This may cause increased sciatic nerve excitability [49]. In the thalamus and periaqueductal areas of the brain, oxaliplatin increases protein kinase C activity and upregulates the gamma isoform associated with neuropathic pain development and the epsilon isoform associated with apoptosis [50,51].

An important difference in the CNS response to CIPN versus other types of neuropathic pain is an apparent lack of recruitment of a microglial response [13]. In contrast, activation of spinal astrocytes appears to play a key role in the neuropathies produced by paclitaxel, oxaliplatin and bortezomib [52–54]. Down-regulation of spinal astrocyte glutamate transporters is potentially linked to the development of excessive after-discharges in spinal neurons evoked by cutaneous stimuli in CIPN [54–56].

Diagnosis of neuropathy

A thorough history and physical exam are sufficient for the diagnosis of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, although electrophysiological and nerve conduction studies will also confirm the presence of neuropathy. Common findings are the loss of deep tendon reflexes, presence of symmetrical numbness or paresthesias in the stocking-glove distribution and pain in the distal extremities [7, 57–60]. Loss of manual dexterity presents itself as clumsiness. Patients may also report concomitant hearing loss, change in taste and smell. Neuropathic pain is typically described as sharp, burning, shooting, electric pain.

The natural history of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy should be recorded with a comprehensive pain assessment algorithm, according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network [61]. This allows for the evaluation of potentially worsening symptoms and the efficacy of treatment. The McGill Pain Questionnaire evaluates the sensory, affective and evaluative nature of pain in addition to pain intensity [61,62], while the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) records pain location, intensity, and interference with daily activities. One advantage of the BPI is the ease of completion in the outpatient setting [63,64].

Although not required, the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy can be confirmed through the use of Quantitative Sensory Testing (QST) to provide an objective means of assessing and quantifying sensory impairments, touch, warmth and heat. Repeat testing over time allows for tracking of changes during the course of care [19]. More invasive diagnostic tests that confirm peripheral neuropathy include skin biopsy for the evaluation of intraepidermal nerve fiber density. The use of EMG/NCS is limited as the small fibers are primarily affected.

Clinical Management

Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy is a distressing side-effect of chemotherapy especially if it is painful and is thus the main focus of treatment. Classes of medications utilized include anticonvulsants, antidepressants, opioids, non-opioid analgesics, and topicals (see Table 2). First-line treatment begins with the calcium channel alpha-2-delta ligand anticonvulsants, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSNRIs) and topical lidocaine. Opioid analgesics and tramadol represent second-line therapy. Third-line therapies include other anticonvulsants and anti-depressant medications, membrane stabilizer such as mexiletine, NMDA receptor antagonists, and topical agents. A multimodal approach may be the most efficacious in managing neuropathic pain. Here we will also discuss non-pharmacological management options.

Table 2.

Commonly used medications for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain.

| Classification | Medication | Starting dosage |

|---|---|---|

| Anticonvulsants | Gabapentina | 100–300 mg at bed time |

| Pregabalina | 25–75 mg at bed time | |

| Carbamazepine | 100 mg every 12 h | |

| Lamotrigine | 50 mg/day | |

| Antidepressants | Amitriptylinea | 10–25 mg/day |

| Nortriptylinea | 10–25 mg/day | |

| Duloxetinea | 30–60 mg/day | |

| Topicals | Lidocaine 5% patcha | 1 patch 12 h on 12 h off |

| Lidocaine creama | Apply every 8 h | |

| Opioids | Hydrocodone/acetaminophen | 5/325 mg every 4 h as needed |

| Morphine | 15 mg every 4 h as needed | |

| Oxycodone | 5 mg every 4 h as needed | |

| Methadone | 2.5 mg every 12 h | |

| Fentanyl patch | 12.5 μg/h every 72 h | |

| Other | Tramadol | 50 mg once to twice a day as needed for pain |

Recommended first-line treatment.

Anticonvulsants

Gabapentin and pregabalin act at voltage-gated calcium channels to block the alpha-2-delta subunit, producing hyperpolarization by decreasing the release of glutamate, norepinephrine, and substance P [65,66]. Of note, they also have other mechanism of actions which is beyond the scope of this review. The recommended starting dose for gabapentin is 100–300 mg once a day at bed time, and subsequently could be titrated up to 3600 mg per day in divided doses, if needed and tolerated. Similarly, the starting dose for pregabalin is 25–75 mg at bed time, and subsequently could be titrated up to 600 mg daily in divided doses. Pregabalin is a relatively newer agent than gabapentin and may be cost-prohibitive for some patients.

In comparison, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, topiramate, and valproic acid have yielded equivocal results in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [67].

Antidepressants

Commonly used TCAs for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy include amitriptyline and nortriptyline, which non-selectively block the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine in the central nervous system. Starting dose for both antidepressants is 10–25 mg daily with maximal dose of 100–150 mg per day, typically taken at bedtime due to a sedating side effect. Other side effects include dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, urinary retention, orthostatic hypotension and hypertension. TCAs have been shown to be efficacious in the treatment of neuropathic pain by several systematic reviews [67] however TCAs have not differed significantly from placebo in RCTs of patients with cisplatin neuropathy [68] and neuropathic cancer pain [69].

SNRIs such as duloxetine and venlafaxine inhibit reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine in the central nervous system. While duloxetine has demonstrated significantly greater pain relief compared with placebo in patients with painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy it has not been studied in other types of neuropathic pain [70–72]. Duloxetine is started at 30 mg per day. At low dosages, venlafaxine inhibits serotonin reuptake; at higher doses it inhibits both serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake. Conflicting results between RCTs in the efficacy of venlafaxine in treating painful polyneuropathies may be accounted for by the differing dosages used, with higher doses (150–225 mg per day) associated with pain relief [65,66].

Other antidepressants that represent third-line medication include citalopram and paroxetine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as well as bupropion, a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor, which have shown limited evidence of efficacy in RCTs for painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy. They may represent treatment options for patients who do not respond to TCAs or SNRIs [67].

Opioid analgesia

While opioids are effective in treating somatic pain, they are not recommended for the long-term treatment of neuropathic pain and are considered second-line therapy. Compared to TCAs and gabapentin, opioids are associated with more frequent side effects [73–75]. Long term opioid therapy raises the risk of developing tolerance, necessitating escalating doses. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia may also develop, further complicating the patient’s overall pain picture [76]. Further, immunologic changes and hypogonadism may arise with prolonged opioid use [77,78]. One benefit of the use of opioid analgesics in first-line therapy is the immediate onset of relief offered while titrating to therapeutic dose of TCAs, SNRIs and anticonvulsants [65,66].

Topical medications

Topical lidocaine is a relatively safe first-line medication for neuropathic pain. Lidocaine acts at the sodium ion channel of nerve membranes to inhibit ion transport, thereby preventing initiation and conduction of nerve impulses. Lidocaine is available as a 5% patch as well as cream, ointment and gel in different concentrations to be directly applied to painful areas. Efficacy is limited by the limited absorption of medication through the skin. The most common adverse effect is a mild local reaction [65,66].

Topical capsaicin has not shown consistent benefit over placebo in patients with painful polyneuropathy [79]. Capsaicin binds to TRPV1 to cause release of substance P, producing a burning sensation and thus depleting substance P stores, blocking action potential from peripheral sites to the central nervous system [80]. Due to the discomfort associated with the use and limited benefit, capsaicin is not commonly used as a topical treatment for painful peripheral neuropathy.

Others

Tramadol has some opioid effects due to its weak mu receptor activity, but also works to inhibit the reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine. Several studies have shown that tramadol has some efficacy in treating neuropathic pain [67]. Tramadol may be started at 50 mg 1–4 times a day as needed with the maximum dose not to exceed 400 mg daily. Although tramadol is less potent than opioid analgesics, it does carry the risk of similar adverse events [65,66]. Tramadol also lowers the seizure threshold and should be used cautiously in the setting of concomitant SSNRI and SSRI therapy as it can cause serotonin syndrome. Therefore it is not recommended to prescribe both tramadol and a tricyclic antidepressant in the multimodal treatment of painful peripheral neuropathy.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have not been shown to be effective in the treatment of neuropathic pain. They may be used as an adjuvant for the treatment of nociceptive pain that may develop alongside neuropathic pain.

Interventional procedure

While some patients with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy may respond well to conservative medical management alone, others may require interventional procedures that span a range of invasiveness from superficial stimulation to permanent implantation of medical devices. Certain contraindications to invasive procedures are of greater concern in the cancer patient, such as thrombocytopenia and neutropenia. In addition life expectancy influences the decision-making process in pursuing spinal cord stimulator or intrathecal pump implantation. It is also important to set expectations with the patient that a procedure does not obviate the need for pharmacotherapy and that the goal is pain control, not elimination of pain.

Non-invasive interventions

TENS

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) units employ electrical fields to directly affect the transmission of pain. The exact mechanism of action is not clear, however, it is generally believed to be due to modulation of the gate control system at the dorsal horn to decrease pain signals through the central nervous system and also stimulation of endogenous neurotransmitters and opioids. Surface electrodes are applied to stimulate cutaneous nerve fibers over a variety of currents, amplitudes, pulse widths and frequencies. High-frequency low-intensity patterns are associated with immediate analgesia and low-frequency high-intensity patterns are associated with longer-lasting analgesia [81].

Physical and occupational therapy

The main goal of pain management is to promote functionality, and physical therapy and occupational therapy represent important modalities in the treatment of debilitating pain in the context of lifestyle improvement and performance in activities of daily living. Depending on severity of neuropathy patients may require assistive devices and retraining in balance and stability, as well as correction of body posture and myofascial tightening. Occupational therapy offers strategies for compensating for fine motor skills lost through the development of sensory neuropathy. Through the prevention of secondary musculoskeletal problems, PT/OT may improve the sequelae of neuropathic pain with the added benefit of returning patients closer to their functional baseline.

Invasive interventions

Sympathetic nerve blocks and sympathetic neurolysis

A sympathetic nerve block is an injection performed at a ganglion of the sympathetic chain, often containing local anesthetic and adjuvants such as centrally acting alpha 2 agonist clonidine. Neuropathic pain at the site of the upper extremity may be treated with a stellate ganglion block, while neuropathic pain at the lower extremity is treated with a lumbar sympathetic block. The vasodilation that occurs post-sympathetic blockade may also improve blood flow to the affected limb. Once a sympathetic block has been shown to provide reduction in pain without causing sensory or motor deficits, neurolysis may be performed to offer more sustained relief. Chemical neurolysis is performed via the injection of 98% alcohol or phenol and allows for larger lesions while radiofrequency neurolysis allows for more controlled lesion [81]. However, neurolysis is also associated with serious side effects such as motor weakness or loss of bowel and bladder tone, and the risk of neuritis — painful inflammation after partial destruction of the nerve. Neurolysis is therefore typically reserved for intractable pain in advanced or terminal malignancy and unilateral pain [81]. Chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy is typically bilateral in the stocking-glove distribution. Sympathetic neurolysis for cancer-related pain is therefore more commonly applied to visceral pain.

Spinal cord stimulators and peripheral nerve stimulators

Spinal cord and peripheral nerve stimulators are permanent implantable devices that treat neuropathic pain through neuromodulation. Leads are placed over specific nerve targets and connected to a programmable implanted pulse generator that allows for different combinations of stimulation over the parameters of amplitude, pulse width, rate and electrode selection [82].

During a spinal cord stimulator trial, leads are threaded through the epidural space under local anesthesia with or without conscious sedation so that the patient may confirm the vertebral level at which sensation of pain is replaced by non-painful paresthesias. Position is identified under fluoroscopy. While the exact mechanism of action for pain relief is unclear, it is thought that spinal cord stimulation may alter local neurochemistry at the dorsal horn, thereby increasing GABA and serotonin and suppressing hyperexcitability of wide dynamic range interneurons [1,83]. Spinal cord stimulation is most effective in neuropathic pain syndromes, and has the added benefit of bilateral extremity coverage of pain. Even so, appropriate patient selection requires psychological screening and clearance [84]. Complications must also be considered, most commonly lead migration or breakage (22% of cases) causing lack of appropriate paresthesia coverage but also including nerve injury, paralysis, and death [85,86,87]. Permanent implantation of spinal cord stimulator is an outpatient surgery performed under local anesthesia and sedation. This technology has been used for various types of neuropathic pain syndromes, however, its use for chemotherapy induced peripheral neuropathy has not been well defined. Nonetheless, Cata, et al. (2004) reported a case study of two patients whose pain and neuropathy symptoms improved with the use of spinal cord stimulator [56].

Peripheral nerve stimulators allow for selective stimulation of nerves of the upper and lower extremities. Due to the superficial location of most target nerves, the procedure may be performed under ultrasound guidance using conventional spinal cord stimulator electrodes. Peripheral nerve stimulation carries greater risk of lead migration than spinal cord stimulation due to the mobility of extremities where it is mostly implanted. One way to minimize this risk is to shorten the distance between the battery and the electrode. The proposed mechanism of action for pain relief includes direct effects on peripheral pain fibers through excitation failure [88], selective release of pain-modulating neurotransmitters [89], and changes in cerebral flow in pain centers [90].

Intrathecal pump

Patients who require high dose systemic opioid therapy or cannot tolerate opioid side effects and have inadequate relief from neuropathic pain are candidates for intrathecal pump implantation for the delivery of analgesia. The potential for intraspinal pharmacotherapy was first elucidated by the discovery of opiate receptors in the substantia gelatinosa of the spinal cord [91]. Multiple receptor systems involved in the transmission and modulation of pain have been discovered since then allowing for the use of other agents including clonidine, baclofen, local anesthetics, and ziconitide. Intrathecal medications carry many times the potency of systemically delivered medications, allowing for reduced dosing and thereby decreasing side effects.

The intrathecal catheter is placed under fluoroscopy and tunneled to a pump located in the lower abdominal quadrant within the fascia. The superficial location of the pump is necessary for percutaneous access to perform pump refill. This increases susceptibility to infection because of frequent access through the skin. In the event of infection, the entire intrathecal system must be removed. The most frequent complication of intrathecal pumps is failure of the system, typically with catheter kinking, obstruction, disconnection, or shearing. Of greater concern is the potential for accidental overdose during pump refill, programming errors or incorrect medication used. More recently, catheter tip granulomas have gained credence as a serious complication that may cause spinal cord and nerve root compression. Granulomas are more commonly seen in younger patients and non-malignant pain. The exact mechanism of granuloma formation is unknown but is correlated with the concentration of opioid and regional cerebrospinal fluid flow dynamics [81].

Complementary and alternative medicine

While complementary and alternative medicine does not present substitutes for pharmacotherapy and interventions, it does provide options for adjuvant therapies that are relatively benign and have few side effects [92]. Massage therapy for cancer patients has been associated with an immediate drop in symptom scores including pain, fatigue, stress, nausea, and depression lasting up to 48 h [93]. Acupuncture is another modality that may offer relief in neuropathic pain, although the mechanism of action is not well understood. Non-herbal nutritional supplements (calcium supplements, vitamin and mineral supplements, fish oil, glucosamine, and selenium) are popular among cancer patients as a method of boosting the immune system, and randomized clinical trials have shown that the incidence and severity of neuropathic pain associated with taxane-agents such as paclitaxel can be reduced with vitamin E, glutamine, and acetyl-L-carnitine [94].

Conclusion

Peripheral neuropathy is a common neurologic side effect of chemotherapy, and chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathic pain is both distressing and debilitating. The type of chemotherapy, dosage and duration of treatment might determine the incidence of neuropathy. Fortunately, it gradually improves with cessation of therapy, except in the case of platinum-based compounds where sensory deficits may continue to progress for several months [57–59]. Currently there is no prevention for chemotherapy-induced painful and non-painful peripheral neuropathy. A step-wise approach to symptom management is therefore essential, as is familiarity with the different treatment options available.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Peripheral neuropathy is a common neurologic side effect of chemotherapy treatment

Functional and anatomical changes occur at the level of peripheral and central nervous system

Diagnosis is generally made at the bedside after through history and physical

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bhagra A, Rao RD. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. Curr Oncol Rep. 2007;9:290–9. doi: 10.1007/s11912-007-0036-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bokhari F, Sawatzky JA. Chronic neuropathic pain in women after breast cancer treatment. Pain Manag Nurs. 2009;10:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albers JW, Chaudhry V, Cavaletti G, et al. Interventions for preventing neuropathy caused by cisplatin and related compounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2:CD005228. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005228.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Polomano RC, Farrar JT. Pain and neuropathy in cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(Suppl 2):39–47. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200603002-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reyes-Gibby C, Morrow PK, Bennett MI, et al. Neuropathic pain in breast cancer survivors: using the ID pain as a screening tool. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:882–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith EM, Pang H, Cirrincione C, et al. Effect of duloxetine on pain, function, and quality of life among patients with chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309:1359–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ezendam NP, Pijlman B, Bhugwandass C, et al. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy and its impact on health-related quality of life among ovarian cancer survivors: results from the population-based PROFILES registry. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;135:510–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cella D, Huang H, Homesley HD, et al. Patient-reported peripheral neuropathy of doxorubicin and cisplatin with and without paclitaxel in the treatment of advanced endometrial cancer: results from GOG 184. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119:538–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahaman J, Steiner N, Hayes MP, et al. Chemotherapy for gynecologic cancers. Mt Sinai J Med. 2009;76:577–88. doi: 10.1002/msj.20143. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/msj.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyette-Davis JA, Cata JP, Zhang H, et al. Follow-up psychophysical studies in patients with bortezomib-related chemoneuropathy. J Pain. 2011;12(9):1017–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyette-Davis JA, Cata JP, Zhang H, et al. Persistent chemoneuropathy in patients receiving the plant alkaloids taxol and vincristine. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71(3):619–26. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-2047-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holland NR, Stocks A, Hauer P, et al. Intraepidermal nerve fiber density in patients with painful sensory neuropathy. Neurology. 1997 Mar;48(3):708–11. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.3.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siau C, Xiao W, Bennett GJ. Paclitaxel- and vincristine-evoked painful peripheral neuropathies: loss of epidermal innervation and activation of Langerhans cells. Exp Neurol. 2006;201:507–14. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boyette-Davis J, Dougherty PM. Protection against oxaliplatin-induced mechanical hyperalgesia and intraepidermal nerve fiber loss by minocycline. Exp Neurol. 2011;229:353–7. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregg RW, Molepo JM, Monpetit VJ, et al. Cisplatin neurotoxicity: the relationship between dosage, time, and platinum concentration in neurologic tissues, and morphologic evidence of toxicity. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:795–803. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.5.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang H, Boyette-Davis JA, Kosturakis AK, et al. Induction of MCP-1/CCR2 in primary sensory neurons contributes to paclitaxel-induced neuropathy. J Pain. 2013;14(10):1031–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Zhang H, Zhang H, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling in primary sensory neurons and spinal astrocytes contribute to paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. J Pain. 2014;15(7):712–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang H, Dougherty PM. Enhanced excitability of primary sensory neurons and altered gene expression of neuronal ion channels in dorsal root ganglion in paclitaxel-induced peripheral neuropathy. Anesthesiology. 2014;120(6):1463–75. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Massey RL, Kim HK, Abdi S. Brief review: chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy (CIPPN): current status and future directions. Can J Anaesth. 2014 Aug;61(8):754–62. doi: 10.1007/s12630-014-0171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun X, Windebank AJ. Calcium in suramin-induced rat sensory neuron toxicity in vitro. Brain Res. 1996;742:149–56. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siau C, Bennett GJ. Dysregulation of cellular calcium homeostasis in chemotherapy-evoked painful peripheral neuropathy. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1485–90. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000204318.35194.ed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao W, Boroujerdi A, Bennett GJ, et al. Chemotherapy-evoked painful peripheral neuropathy: analgesic effects of gabapentin and effects on expression of the alpha-2-delta type-1 calcium channel subunit. Neuroscience. 2007;144:714–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsumoto G, Ichikawa M, Tasaki A, et al. Axonal microtubules necessary for generation of sodium current in squid giant axons: I. Pharmacological study on sodium current and restoration of sodium current by microtubule proteins and 260 K protein. J Membr Biol. 1984;77:77–91. doi: 10.1007/BF01925858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nieto FR, Entrena JM, Cendan CM, et al. Tetrodotoxin inhibits the development and expression of neuropathic pain induced by paclitaxel in mice. Pain. 2008;137:520–31. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghelardini C, Desaphy JF, Muraglia M, et al. Effects of a new potent analog of tocainide on hNav1. 7 sodium channels and in vivo neuropathic pain models. Neuroscience. 2010;169:863–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Descoeur J, Pereira V, Pizzoccaro A, et al. Oxaliplatin-induced cold hypersensitivity is due to remodelling of ion channel expression in nociceptors. EMBO Mol Med. 2011;3:266–78. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flatters SJ, Bennett GJ. Studies of peripheral sensory nerves in paclitaxel-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction. Pain. 2006;122:245–57. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.01.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Melli G, Taiana M, Camozzi F, et al. Alpha-lipoic acid prevents mitochondrial damage and neurotoxicity in experimental chemotherapy neuropathy. Exp Neurol. 2008;214:276–84. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Broyl A, Corthals SL, Jongen JL, et al. Mechanisms of peripheral neuropathy associated with bortezomib and vincristine in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a prospective analysis of data from the HOVON-65/GMMG-HD4 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:1057–65. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joseph EK, Chen X, Bogen O, et al. Oxaliplatin acts on IB4-positive nociceptors to induce an oxidative stress-dependent acute painful peripheral neuropathy. J Pain. 2008;9:463–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.01.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim HK, Zhang YP, Gwak YS, et al. Phenyl N-tert-butylnitrone, a free radical scavenger, reduces mechanical allodynia in chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain in rats. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:432–9. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ca31bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Muthuraman A, Jaggi AS, Singh N, et al. Ameliorative effects of amiloride and pralidoxime in chronic constriction injury and vincristine induced painful neuropathy in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;587:104–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joseph EK, Levine JD. Caspase signalling in neuropathic and inflammatory pain in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:2896–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boehmerle W, Zhang K, Sivula M, et al. Chronic exposure to paclitaxel diminishes phosphoinositide signaling by calpain-mediated neuronal calcium sensor-1 degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11103–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701546104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alessandri-Haber N, Dina OA, Joseph EK, et al. Interaction of transient receptor potential vanilloid 4, integrin, and SRC tyrosine kinase in mechanical hyperalgesia. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1046–57. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4497-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ta LE, Bieber AJ, Carlton SM, et al. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 is essential for cisplatin-induced heat hyperalgesia in mice. Mol Pain. 2010;6:15. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anand U, Otto WR, Anand P. Sensitization of capsaicin and icilin responses in oxaliplatin treated adult rat DRG neurons. Mol Pain. 2010;6:82. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horvath P, Szilvassy J, Nemeth J, et al. Decreased sensory neuropeptide release in isolated bronchi of rats with cisplatin-induced neuropathy. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;507:247–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jamieson SM, Liu JJ, Connor B, et al. Nucleolar enlargement, nuclear eccentricity and altered cell body immunostaining characteristics of large-sized sensory neurons following treatment of rats with paclitaxel. Neurotoxicology. 2007;28:1092–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thibault K, Van Steenwinckel J, Brisorgueil MJ, et al. Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor involvement and Fos expression at the spinal level in vincristine-induced neuropathy in the rat. Pain. 2008;140:305–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hansen N, Uceyler N, Palm F, et al. Serotonin transporter deficiency protects mice from mechanical allodynia and heat hyperalgesia in vincristine neuropathy. Neurosci Lett. 2011;495:93–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Adelsberger H, Quasthoff S, Grosskreutz J, et al. The chemotherapeutic oxaliplatin alters voltage-gated Na(+) channel kinetics on rat sensory neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;406:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00667-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grolleau F, Gamelin L, Boisdron-Celle M, et al. A possible explanation for a neurotoxic effect of the anticancer agent oxaliplatin on neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:2293–7. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park SB, Krishnan AV, Lin CS, et al. Mechanisms underlying chemotherapy-induced neurotoxicity and the potential for neuroprotective strategies. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15:3081–94. doi: 10.2174/092986708786848569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meijer C, de Vries EG, Marmiroli P, et al. Cisplatin-induced DNA-platination in experimental DRG neuronopathy. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:883–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Argyriou AA, Koltzenburg M, Polychronopoulos P, et al. Peripheral nerve damage associated with administration of taxanes in patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;66:218–28. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peters CM, Jimenez-Andrade JM, Jonas BM, et al. Intravenous paclitaxel administration in the rat induces a peripheral sensory neuropathy characterized by macrophage infiltration and injury to sensory neurons and their supporting cells. Exp Neurol. 2007;203:42–54. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cata JP, Weng HR, Chen JH, et al. Altered discharges of spinal wide dynamic range neurons and down-regulation of glutamate transporter expression in rats with paclitaxel-induced hyperalgesia. Neuroscience. 2006;138:329–38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kassem LA, Gamal El-Din MM, et al. Mechanisms of vincristine-induced neurotoxicity: possible reversal by erythropoietin. Drug Discov Ther. 2011;5:136–43. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2011.v5.3.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Norcini M, Vivoli E, Galeotti N, et al. Supraspinal role of protein kinase C in oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy in rat. Pain. 2009;146:141–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galeotti N, Vivoli E, Bilia AR, et al. St. John’s Wort reduces neuropathic pain through a hypericin-mediated inhibition of the protein kinase Cgamma and epsilon activity. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;79:1327–36. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang H, Yoon S-Y, Zhang H, et al. Evidence that spinal astrocytes but not microglia contribute to the pathogenesis of paclitaxel-induced painful neuropathy. J Pain. 2012;13(3):293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoon S-Y, Robinson CR, Zhang H, et al. Spinal astrocyte gap junctions contribute to oxaliplatin-induced mechanical hypersensitivity. J Pain. 2012;14(2):205–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robinson CR, Zhang H, Dougherty PM. Astrocytes, but not microglia, are activated in oxaliplatin and bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy in the rat. Neuroscience. 2014;274(1):308–17. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cata JP, Weng HR, Dougherty PM. Behavioral and electrophysiological studies in rats with cisplatin-induced chemoneuropathy. Brain Res. 2008;1230:91–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cata JP, Cordella JV, Burton AW. Spinal cord stimulation relieves chemotherapy-induced pain: a clinical case report. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2004;27:72–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boyette-Davis JA, Cata JP, Driver LC, et al. Persistent chemoneuropathy in patients receiving the plant alkaloids paclitaxel and vincristine. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:619–26. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-2047-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Farquhar-Smith P. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2011;5:1–7. doi: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e328342f9cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Windebank AJ, Grisold W. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2008;13:27–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2008.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Urch CE, Dickenson AH. Neuropathic pain in cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1091–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burton AW, Fine PG, Passik SD. Transformation of acute cancer pain to chronic cancer pain syndromes. J Support Oncol. 2012;10:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Melzack R. The McGill Pain Questionnaire: major properties and scoring methods. Pain. 1975;1:277–99. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(75)90044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cleeland CS, Gonin R, Hatfield AK, et al. Pain and its treatment in outpatients with metastatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:592–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403033300902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23:129–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Backonja M, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132:237–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Audette J, et al. Recommendations for the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain: an overview and literature update. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(Suppl 3):S3–S14. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Finnerup NB, Otto M, Jensen TS, et al. Algorithm for neuropathic pain treatment: an evidence based proposal. Pain. 2005;118:289–305. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hammack JE, Michalak JC, Loprinzi CL, et al. Phase III evaluation of nortriptyline for alleviation of symptoms of cis-platinum-induced peripheral neuropathy. Pain. 2002;98:195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mercadante S, Arcuri E, Tirelli W, et al. Amitriptyline in neuropathic cancer pain in patients on morphine therapy: a randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind crossover study. Tumori. 2002;88:239–42. doi: 10.1177/030089160208800310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Goldstein DJ, Lu Y, Detke MJ, et al. Duloxetine vs. placebo in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy. Pain. 2005;116:109–18. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Raskin J, Pritchett YL, Wang F, et al. A double-blind, randomized multicenter trial comparing duloxetine with placebo in the management of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain Med. 2005;6:346–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.00061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wernicke JF, Pritchett YL, D’Souza DN, et al. A randomized controlled trial of duloxetine in diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain. Neurology. 2006;67:1411–20. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000240225.04000.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Khoromi S, Cui L, Nackers L, et al. Morphine, nortriptyline and their combination vs. placebo in patients with chronic lumbar root pain. Pain. 2007;130:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Raja SN, Haythornthwaite JA, Pappagallo M, et al. Opioids versus antidepressants in postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2002;59:1015–21. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.7.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gilron I, Bailey JM, Tu D, et al. Morphine, gabapentin, or their combination for neuropathic pain. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1324–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Angst MS, Clark JD. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:570–87. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200603000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Daniell HW. Hypogonadism in men consuming sustained-action oral opioids. J Pain. 2002;3:377–84. doi: 10.1054/jpai.2002.126790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rajagopal A, Vassilopoulou-Sellin R, Palmer JL, et al. Symptomatic hypogonadism in male survivors of cancer with chronic exposure to morphine. Cancer. 2004;100:851–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mason L, Moore RA, Derry S, et al. Systematic review of topical capsaicin for the treatment of chronic pain. BMJ. 2004;328:991–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38042.506748.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wallace M, Pappagallo M. Qutenza®: a capsaicin 8% patch for the management of postherpetic neuralgia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11:15–27. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Benzon Honorio T, Raja Srinivasa N, Liu Spencer S, Fishman Scott M, Cohen Steven P. Essentials of pain medicine. 3. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alfano S, Darwin J, Picullel B. Spinal cord stimulation: patient management guidelines for clinicians. MN: Medtronic Inc. Minneapolis; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Oakley J, Prager J. Spinal cord stimulation. Mechanism of action. Spine. 2002;22:2574–83. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200211150-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Olson KA, Bedder MD, Anderson VC, et al. Psychological variables associated with outcome of spinal cord stimulation trials. Neuromodulation. 1998;1:6–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1403.1998.tb00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Turner JA, Loeser JD, et al. Spinal cord stimulation for patients with failed back surgery syndrome or complex regional pain syndrome. A systematic review of effectiveness and complications. Pain. 2004;108:137–47. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Reig E, Abejan D. Spinal cord stimulation. A 20-year retrospective analysis in 260 patients. Neuromodulation. 2009;12:232–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1403.2009.00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cameron T. Safety and efficacy of spinal cord stimulation for the treatment of chronic pain. A 20-year literature review. J Neurosurg. 2004;100(Suppl 3):254–67. doi: 10.3171/spi.2004.100.3.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Torebjork HE, Hallin RG. Responses in human A and C fibres to repeated electrical intradermal stimulation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1974;37:653–64. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.37.6.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Linderoth B, Gazelius B, Franck J, et al. Dorsal column stimulation induces release of serotonin and substance P in the cat dorsal horn. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:289–96. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199208000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Matharu MS, Bartsch T, Ward N, et al. Central neuromodulation in chronic migraine patients with suboccipital stimulators. A PET study Brain. 2004;127:220–30. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Basbaum AI, Clanton CH, Fields HL. Opiate and stimulus-produced analgesia. Functional anatomy of a medullospinal pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1976;73(12):4685–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.12.4685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cassileth BR, Keefe FJ. Integrative and behavioral approaches to the treatment of cancer-related neuropathic pain. Oncologist. 2010;15(Suppl 2):19–23. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-S504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cassileth BR, Vickers AJ. Massage therapy for symptom control: outcome study at a major cancer center. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:244–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ben-Arye E, Polliack A, Schiff E, et al. Advising patients on the use of non-herbal nutritional supplements during cancer therapy: a need for doctor-patient communication. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013 Dec;46(6):887–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]