Abstract

Background

Anopheles sinensis is a primary vector for Plasmodium vivax malaria in most regions of China. A comprehensive understanding of genetic variation and structure of the mosquito would be of benefit to the vector control and in a further attempt to contribute to malaria elimination in China. However, there is only inadequate population genetic data pertaining to An. sinensis currently.

Methods

Genetic variations and structure among populations of An. sinensis was examined and analyzed based on the nucleotide sequences of a 662 nt variable region of the mitochondrial cox1 gene among 15 populations from 20 collection sites in China.

Results

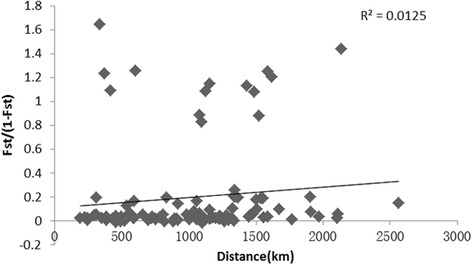

A total of 453 individuals in 15 populations were analyzed. The cox1 gene sequences were aligned, and 247 haplotypes were detected, 41 of these shared between populations. The range of haplotype diversity was from 0.709 (Yunnan) to 0.998 (Anhui). The genealogic network showed that the haplotypes were divided into two clusters, cluster I was at a high level of homoplasy, while cluster II included almost all individuals from the Yunnan population. The Yunnan population displayed a significantly high level of genetic differentiation (0.452−0.622) and a restricted gene flow with other populations. The pairwise F ST values among other populations were lower. The AMOVA result showed that the percentage of variation within populations (83.83%) was higher than that among populations (16.17%). Mantel test suggested that geographical distance did not significantly contribute to the genetic differentiation (R 2 = 0.0125, P = 0.59). Neutral test and mismatch analysis results showed that the An. sinensis population has undergone demographic expansions.

Conclusions

Anopheles sinensis populations showed high genetic polymorphism by cox1 gene. The weak genetic structure may be a consequence of low genetic differentiation and high gene flow among populations, except the Yunnan samples. The Yunnan population was isolated from the other populations, gene flow limited by geographical distance and barriers. These findings will provide a theoretical basis for vector surveillance and vector control in China.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13071-017-2013-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Anopheles sinensis, Genetic variation, Population structure, cox1

Background

Anopheles sinensis Wiedemann is an Oriental species with a wide distribution in China [1]. It is the primary malaria vector in plain regions of central China, especially in the paddy planting areas, and it has also been identified as a pathogenic vector for other disease such as Brugia malayi, one type of lymphatic filariasis [2, 3]. Despite its disputable malaria vector capacity, An. sinensis is still incriminated as a competent vector for Plasmodium vivax malaria due to its abundant population size and wide distribution, which have led to occasional local malaria epidemics or outbreaks throughout history [4, 5].

The morbidity of P. vivax malaria has dropped down to a historically low level since the Chinese government initiated the National Malaria Elimination Action Plan Programme in 2010 [6]; however, the ecological habitat and distribution of An. sinensis has not changed significantly [7, 8]. In addition, the proportion of imported P. vivax malaria cases has notably increased in recent years [9, 10], and so increased knowledge on the genetic structure and the divergence among An. sinensis populations are essential to lay out effective strategies for vector control and further malarial elimination.

As one important member of the Hyrcanus group, An. sinensis has been differentiated from its morphologically indistinguishable sibling species (An. lesteri, An. yatsushiroensis, and so on) by comparison of sequence data from the second internal transcribed spacer (ITS2) region of the ribosomal DNA (rDNA), which also greatly facilitates the subsequent genetics study [11].

To date, An. sinensis populations in China exhibit variations in morphology [12], chromosomes [13, 14], ecology [12, 14], vector capacity [15], the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) NADH dehydrogenase subunit 5 (nad5) [16] and mtDNA control region [17]. Our research team applied random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPDs) [18] and microsatellite DNA markers [19] to detect the genetic structure of An. sinensis samples, the results revealing considerable polymorphism among populations, the genetic divergence however did not correlate with geographical distance. There were two gene pools in An. sinensis populations inferred by microsatellites, these structured populations possibly limiting the migration of genes under pressures/selections, such as insecticides and immune genes against malaria [20].

Different molecular markers may demonstrate different genetic structures. The appropriate markers are usually neutral, such as the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (cox1) gene, which was used to analyze genetic variation and population structure of the anopheline mosquitoes [21–27]. The cox1 gene is slowly evolving compared to other protein-coding mitochondrial genes and is also widely used for reconstructing molecular phylogenies [28]. Although a few Chinese An. sinensis population genetic studies have been reported [16, 18, 19], to obtain a more accurate genetic structure of these populations, more molecular markers and more specimens are needed. In the present study, we sought to elucidate the genetic properties and variability of the An. sinensis populations collected from almost all distribution regions in China based on the sequences of the cox1 gene.

Methods

Mosquito collection and identification

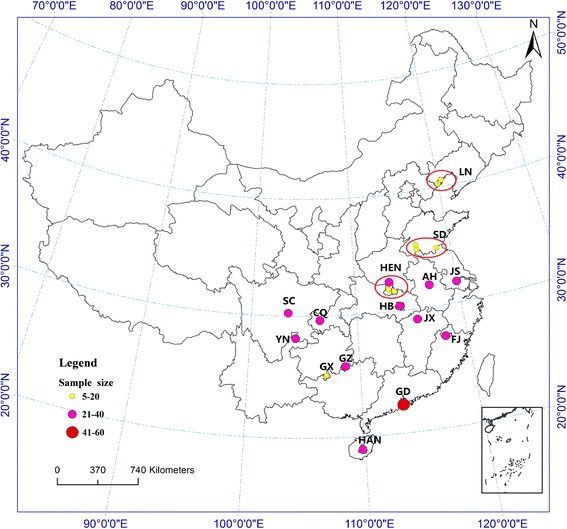

Wild mosquito adults were caught from July 1997 to August 2010 by light traps or artificial catching aspirator at livestock corrals. With the owners’ consent, the light traps were set up in pig or cow pens from 18:30 pm to 8:30 am. The number of sampling sites was 20 in 15 provinces from China. The collection information was summarized in Tables 1 and Fig. 1. Mosquitoes of the An. hyrcanus group were sorted out in the field by morphology using the identification keys [1], and kept individually in silica gel filled tubes at 4 °C until DNA extraction. The An. sinensis species identity was diagnosed by PCR assay based on ITS2 rDNA sequences [11].

Table 1.

Collection information of Anopheles sinensis populations in this study

| Population code | Collection site | Date | Coordinates | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AH | Hefei, Anhui | July 2006 | 31°49′N, 117°13′E | 29 |

| HB | Wuhan, Hubei | August 2006 | 30°35′N, 114°17′E | 25 |

| FJ | Jianyang, Fujian | September 1997 | 27°20′N, 118°06′E | 30 |

| CQ | Kaixian, Chongqing | July 2008 | 29°34′N, 106°32′E | 24 |

| HEN | Nanyang, Henan | August 2007 | 32°59′N, 112°31′E | 39 |

| Guangshui, Hubei | June 2007 | 31°37′N, 113°49′E | 6 | |

| Shuizhou, Hubei | June 2007 | 31°41′N, 113°22′E | 5 | |

| JS | Wujing, Jiangsu | July 1997 | 31°48′N, 119°58′E | 40 |

| GZ | Kaili, Guizhou | August 2007 | 26°34′N, 107°58′E | 26 |

| JX | Yongxiu, Jiangxi | September 2009 | 29°42′N, 109°83′E | 28 |

| GD | Zhuhai, Guangdong | October 2007 | 22°16′N, 113°34′E | 46 |

| SD | Jining, Shandong | July 2007 | 35°41′N, 116°34′E | 14 |

| Yutai, Shandong | July 2000 | 35°01′N, 116°65′E | 13 | |

| Linshu, Shandong | July 2000 | 34°91′N, 118°66′E | 10 | |

| HAN | Qiongzhong, Hainan | August 2010 | 39°28′N, 106°91′E | 24 |

| GX | Tiane, Guangxi | July 2005 | 24°99′N, 107°18′E | 18 |

| LN | Suizhong, Liaoning | August 2008 | 40°29′N, 120°01′E | 7 |

| Xingcheng, Liaoning | August 2008 | 40°61′N, 120°75′E | 8 | |

| SC | Pujiang, Sichuan | July 1997 | 30°19′N, 103°51′E | 33 |

| YN | Yanjin, Yunnan | July 2006 | 28°10′N, 104°23′E | 28 |

Fig. 1.

Schematic map of China showing sampling sites for Anopheles sinensis. The colour of the circles indicates the sample size of the collecting localities, the legend marked on the map (see Table 1 for abbreviations)

Genomic DNA isolation and sequencing of the cox1 mitochondrial gene fragments

The genomic DNA of single mosquitoes were isolated using QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturer’s protocol. The forward (5′-GGT CAA CAA ATC ATA AAG ATA TTG G-3′) and reverse (5′-AAA CTT CAG GGT GAC CAA AAA ATC A-3′) primers were synthesized to amplify cox1 fragments [29]. The PCR kit was from Aidlab, China. PCR reactions were carried out in a Verity 96 well 157 Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster, USA). The cycling parameter included an initial step of denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of amplification at 94 °C for 30 s, 45 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, with a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 min. After electrophoresis, PCR products were purified and sequenced in both directions using PCR primers on an ABI 3730 automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster, USA) by Biosune Biotech (Shanghai Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The electropherograms were inspected manually to verify sequence quality.

Data analyses

Multiple cox1 sequence alignments were performed by CLUSTAL X [30] and edited by MEGA 6.0 [31]. The sequence differences within populations with number of haplotypes (H), the haplotype diversity (Hd), average number of nucleotide differences (K), average number of mutations per sequence (θ), number of variable sites (S) and nucleotide diversity (Pi) were estimated using DnaSP [32]. Median-joining networks of all An. sinensis haplotypes were constructed using Network 5.0 [33] to visualize relationships among unique haplotypes.

The genetic structure was analyzed with 15 populations. The percentage of sequence divergence within and between populations was calculated based on Nei & Li [34]. The pairwise F ST values for short-term genetic distance between populations were estimated with the methods of Slatkin [35] and tested for significance by permutation. The gene flow [Nm = (1 - F ST)/4 F ST]) between localities was estimated from pairwise F ST [36]. Mismatch distributions and hierarchical analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) were calculated using ARLEQUIN 3.11 [37]. Significant correlation between population genetic distance and linear straight geographical distances were assessed using the Mantel test implemented in Isolation by Distance Web Service (IBDWS) and significance was evaluated based on 1,000 permutations [38]. The neutrality test was evaluated by Tajima’s D and Fu’s Fs, which was estimated using the DnaSP software program [32].

Results

Population sampling and An. sinensis identification

Mosquito samples were collected from 20 sites in 15 provinces in China. Fifteen populations were analyzed, in which HEN, SD and LN consisted of specimens collected from two or three sites in proximity to each other (these were pooled, as stated in Table 1). There were 453 individuals of An. sinensis mosquitoes, which were identified by PCR assay.

Sequence characteristics of cox1 gene

A segment of mtDNA, corresponding to the coding region of cox1, was successfully amplified from An. sinensis individuals. A sequence of 662 nt was obtained and analyzed. No insertion or deletion was detected across all samples. The conserved sites were 553, variable sites 107. Of these, 41 were singleton and 66 were parsimony-informative.

The average number of nucleotide differences (K) ranged from 2.61 (LN) to 6.97 (HAN), corresponding with the range of nucleotide diversity (Pi) and average number of mutations (θ), which were 0.00394 ± 0.00084 (mean ± standard deviation, SD) (LN) - 0.01054 ± 0.00145 (HAN) and 0.007 (LN/GX) - 0.019 (HB), respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary data for populations, haplotypes and nucleotide diversity of Anopheles sinensis

| Population codea | Sample size | H/Percentage | S | K | θ | Hd ± SD | Pi ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AH | 29 | 28/96.55 | 37 | 5.26 | 0.015 | 0.998 ± 0.010 | 0.00795 ± 0.00105 |

| CQ | 24 | 21/87.50 | 26 | 4.68 | 0.011 | 0.989 ± 0.015 | 0.00708 ± 0.00113 |

| FJ | 30 | 26/86.67 | 32 | 5.51 | 0.013 | 0.989 ± 0.013 | 0.00833 ± 0.00114 |

| GD | 46 | 31/67.39 | 35 | 5.11 | 0.012 | 0.974 ± 0.011 | 0.00772 ± 0.00093 |

| GX | 18 | 12/66.67 | 16 | 3.66 | 0.007 | 0.935 ± 0.041 | 0.00553 ± 0.00105 |

| GZ | 26 | 23/88.46 | 31 | 5.37 | 0.014 | 0.982 ± 0.020 | 0.00811 ± 0.00128 |

| HAN | 24 | 19/79.17 | 28 | 6.97 | 0.012 | 0.960 ± 0.031 | 0.01054 ± 0.00145 |

| HEN | 50 | 42/84.00 | 53 | 6.71 | 0.012 | 0.993 ± 0.005 | 0.01014 ± 0.00099 |

| HB | 25 | 22/88.00 | 29 | 4.84 | 0.019 | 0.987 ± 0.017 | 0.00731 ± 0.00118 |

| JS | 40 | 33/82.50 | 41 | 4.67 | 0.015 | 0.983 ± 0.012 | 0.00706 ± 0.00081 |

| JX | 28 | 24/85.17 | 28 | 4.68 | 0.011 | 0.981 ± 0.018 | 0.00707 ± 0.00068 |

| LN | 15 | 10/66.67 | 14 | 2.61 | 0.007 | 0.914 ± 0.056 | 0.00394 ± 0.00084 |

| SD | 37 | 28/75.68 | 35 | 6.28 | 0.010 | 0.973 ± 0.016 | 0.00949 ± 0.00122 |

| SC | 33 | 17/51.52 | 26 | 3.42 | 0.013 | 0.911 ± 0.032 | 0.00516 ± 0.00066 |

| YN | 28 | 10/35.71 | 25 | 6.01 | 0.010 | 0.709 ± 0.091 | 0.00908 ± 0.00207 |

Abbreviations: H number of haplotypes, S the number of segregating sites, K the average number of nucleotide differences, θ the average number of mutations per sequence, Hd the haplotypes diversity, Pi is nucleotide diversity

aPopulation codes as in Table 1

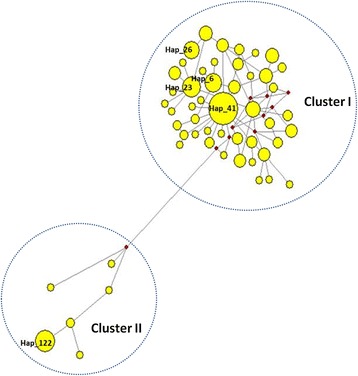

A total of 247 haplotypes (GenBank accession numbers: KX779529–KX779775) were detected in 453 (247/453; 54.53%) of the An. sinensis individuals (Additional file 1: Table S1). The range of haplotypes diversity (Hd) was from 0.709 ± 0.091 (mean ± standard deviation, SD) (YN) to 0.998 ± 0.010 (AH), corresponding to the percentage of the haplotype from 35.71% (YN) to 96.55% (AH). There were five abundant haplotypes, containing more than 10 individuals, as Hap_41 (n = 37), Hap_122 (n = 16), Hap_23 (n = 14), Hap_6 (n = 13) and Hap_26 (n = 10). Forty-one haplotypes occurred in more than one population, the frequency of which was 16.6% (41/247). Few haplotypes were not detected. The genealogic network showed that the haplotypes were divided into two clusters (Fig. 2). Cluster I included 241 detected haplotypes at a high level of homoplasy, Hap_41 being the central haplotype. Cluster II included seven haplotypes, Hap_122 being considered central. The samples in haplotype Hap_122 were almost all from the YN population, except one from HEN. The individuals of the other five detected haplotypes were from AH, HEN, HB, JS and GZ populations.

Fig. 2.

Haplotype network of the cox1 as calculated by Network 5.0. Each circle (yellow) represents a haplotype, and the size of a circle is proportional to the number of individuals that contained the haplotype, the red dots (median vector) are a hypothesised haplotype, which was not detected

Genetic variation among populations

The fixation index (F ST) was used to evaluate the genetic distance among populations. In this study there were seven negative F ST values, comprising AH/FJ, CQ/JX, FJ/GZ, FJ/HEN, FJ/JS, HB/GZ and HB/JS, which indicated genetic differentiation among these populations was very limited (Table 3). Across all populations, F ST values of the YN population were all greater than 0.45, and correspondingly, the gene flow (Nm) of the YN population were all much less than 1.0. In theory, it was hard to prevent genetic divergence caused by genetic drift if the gene flow (Nm) value was less than 1.0 [36].

Table 3.

Pairwise genetic distance (F ST) and gene flow (Nm) for populations of Anopheles sinensis in China. Below diagonal were genetic distance (F ST) and above were gene flow (Nm) among populations

| Population codea | AH | CQ | FJ | GD | GX | GZ | HAN | HB | HEN | JS | JX | LN | SC | SD | YN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AH | 6.509 | -28.152 | 3.979 | 7.570 | 18.407 | 10.325 | 5.039 | 346.972 | 11.857 | 5.258 | 2.569 | 1.261 | 5.725 | 0.222 | |

| CQ | 0.037 | 11.319 | 4.078 | 10.605 | 10.167 | 2.716 | 8.547 | 8.440 | 17.866 | -30.812 | 10.931 | 1.344 | 11.454 | 0.201 | |

| FJ | -0.009 | 0.022 | 13.608 | 13.842 | -15.193 | 5.359 | 41.909 | -43.503 | -117.072 | 10.276 | 3.974 | 1.434 | 15.239 | 0.232 | |

| GD | 0.059 | 0.058 | 0.018 | 4.037 | 25.028 | 2.187 | 44.795 | 6.385 | 11.145 | 4.773 | 2.951 | 1.171 | 4.663 | 0.223 | |

| GX | 0.032 | 0.023 | 0.018 | 0.058 | 26.233 | 3.832 | 13.570 | 10.038 | 88.089 | 11.346 | 10.797 | 1.294 | 5.642 | 0.187 | |

| GZ | 0.013 | 0.024 | -0.017 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 5.022 | -37.844 | 51.942 | 89.036 | 13.426 | 5.108 | 1.597 | 11.356 | 0.228 | |

| HAN | 0.024 | 0.084 | 0.045 | 0.103 | 0.061 | 0.047 | 2.512 | 7.064 | 2.753 | 2.711 | 1.392 | 1.400 | 3.339 | 0.285 | |

| HB | 0.047 | 0.028 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.018 | -0.007 | 0.091 | 24.164 | -40.638 | 7.768 | 7.003 | 1.560 | 9.581 | 0.229 | |

| HEN | 0.001 | 0.029 | -0.006 | 0.038 | 0.024 | 0.005 | 0.034 | 0.010 | 26.459 | 6.385 | 3.594 | 1.617 | 12.730 | 0.298 | |

| JS | 0.021 | 0.014 | -0.002 | 0.022 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.083 | -0.006 | 0.009 | 9.839 | 11.471 | 1.317 | 9.880 | 0.213 | |

| JX | 0.045 | -0.008 | 0.024 | 0.050 | 0.022 | 0.018 | 0.084 | 0.031 | 0.038 | 0.025 | 9.516 | 1.343 | 6.442 | 0.201 | |

| LN | 0.089 | 0.022 | 0.059 | 0.078 | 0.023 | 0.047 | 0.152 | 0.034 | 0.065 | 0.021 | 0.026 | 1.163 | 3.132 | 0.153 | |

| SC | 0.165 | 0.157 | 0.148 | 0.176 | 0.162 | 0.135 | 0.152 | 0.138 | 0.134 | 0.160 | 0.157 | 0.177 | 0.947 | 0.156 | |

| SD | 0.042 | 0.021 | 0.016 | 0.051 | 0.042 | 0.022 | 0.070 | 0.025 | 0.019 | 0.025 | 0.037 | 0.074 | 0.209 | 0.284 | |

| YN | 0.529 | 0.554 | 0.519 | 0.529 | 0.572 | 0.523 | 0.467 | 0.522 | 0.456 | 0.540 | 0.555 | 0.620 | 0.616 | 0.469 |

aPopulation codes as in Table 1

In the hierarchical AMOVA, both the ‘among populations’ and ‘within populations’ variance components were considerably high, the latter (83.83%) contributing more to total variances than the former (Table 4). The mean genetic divergence among populations was 0.16 by cox1 sequences.

Table 4.

AMOVA analysis of genetic variation in Anopheles sinensis populations by mitochondrial cox1 gene. Mean F ST = 0.16

| Source of variation | Degrees of freedom | Variance components | Variation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Among populations | 14 | 0.50 | 16.17 |

| Within populations | 438 | 2.61 | 83.83 |

| Total | 452 | 3.12 | 100 |

Tests of isolation by distance were performed for all of the populations. No statistically significant correlations were detected between genetic differentiation and geographical distances based on the Mantel test (Fig. 3). The correlation coefficient was 0.11, which is not significant based on 1,000 permutations (P = 0.59). The results suggested that geographical distance does not significantly contribute to the genetic differentiation observed in An. sinensis populations.

Fig. 3.

Correlation of the genetic variation and geographical distance for pairwise comparisons of Anopheles sinensis populations

Neutrality test and mismatch analysis

The Tajima’s D and Fu’s Fs values were all negative (Table 5) by DnaSP software, which suggested many low-frequency mutations in populations as well as that the populations were in the process of expansion. The strongly negative values of Fu’s Fs were observed (P < 0.01) in each population, which would be more sensitive in detecting deviations from neutrality.

Table 5.

Mismatch and neutrality tests results of Anopheles sinensis populations from China

| Population code | Neutrality tests | Mismatch analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tajima’s D | Fu’s F S | SSD | Rag | |

| AH | -1.63 | -25.48 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| CQ | -1.22 | -25.46* | 0 | 0.03 |

| FJ | -1.15 | -25.41* | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| GD | -1.22 | -25.51* | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| GX | -0.81 | -19.6* | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| GZ | -1.26 | -25.43* | 0.07 | 0.02 |

| HAN | -0.26 | -21.4* | 0 | 0.01 |

| HEN | -1.5 | -25.12* | 0.07* | 0.01 |

| HB | -1.38 | -25.57* | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| JS | -1.81 | -25.63* | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| JX | -1.27 | -25.65* | 0 | 0.02 |

| LN | -1.56 | -17.64* | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| SD | -0.88 | -25.22* | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| SC | -1.64 | -26.09* | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| YN | -0.23 | -25.3* | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| Mean | -1.19 | -24.3* | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| SD | 0.45 | 2.48 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: SSD sum of squared deviation, Rag raggedness index

*P < 0.01

Demographic expansions were analyzed using mismatch analysis; both the sum of squared deviation (SSD) values (0.03, P = 0.24) and raggedness index (Rag) (0.03) were not statistically significant in almost all the populations except the SSD value for the HEN population (Table 5) [39]. The mismatch distributions showed a smooth and main unimodal curve peaks (Additional file 2: Figure S1), which coincide with the population expansion model.

Discussion

In this study, the population genetic diversity was analyzed on An. sinensis samples obtained from 20 collection sites (22°16′N to 40°61′N, 103°51′E to 120°75′E), which covered almost the entire distribution range of An. sinensis in China [1]. Sample sizes and site distribution throughout China were adequate and provided an ample dataset to study. The results should be an objective representation, since sampling strategy and geographical coverage greatly influence the analysis and interpretation of the data generated from the samples.

There is considerable cox1 gene nucleotide diversity in anopheline mosquitoes, which has been used to explore population genetic structure [21–26] and DNA barcoding [27, 40–44]. The results showed that genetic polymorphism of An. sinensis populations have a high haplotype diversity (Hd = 0.709–0.998) and nucleotide diversity (Pi = 0.004–0.011), in turn suggesting that cox1 can be considered a suitable molecular marker for calculating genetic variation and detecting genetic structure. The high level of genetic diversity indicated that the species could maintain a relatively large effective population size by a broad tolerance to environmental and habitat pressure. Due to the evolutionary rates of different molecular markers, the genetic divergence showed different degrees, e.g. Pi values as 0.61−1.00 of cox1 gene, compared to 0.24−0.65 of cox2 in An. sinensis samples [27]; θs values as 0.58−4.285 of cox2, while as 0.274−3.545 of cytb in An. lesteri populations [45].

Overall, the results showed that there were low genetic differences and high gene flow among different populations except in the case of the YN population, which was similar with that previously detected in An. sinensis populations in China using microsatellites and other molecular markers. There was also no correlation between genetic differences and geographical distance [16, 18, 19, 46]. The distribution range of An. sinensis in China was wide, with a large population size and similar ecological habit [1]. Gene flow and introgression between individuals occurred easily, the expansion and spread of genes responsible for immunity against malaria or insecticide resistance thus highly probable between the populations [20, 47]. Yunnan, a mountainous area in southwest China, is noted as a center of biodiversity because of its highly complex topography [48, 49]. It was obvious that the YN population of An. sinensis was relatively unique in this study as in other reports [16, 46]. The finding also reported that there was a great difference between YN and other populations in the pyrethroid resistance mechanism [47, 50]. Therefore, both physical distance and heterogeneous landscape could be factors inhibiting gene flow between the YN population and others. In the Republic of Korea (ROK), An. sinensis populations represented positive and significant isolation-by-distance patterns by microsatellites and mtDNA control region, and both molecular markers showed the Taebaek and Sobaek Mountain ranges to be barriers between the northern and southern parts of the ROK [17, 51].

The genealogy network showed that these haplotypes of An. sinensis were divided into two clusters. Cluster I included all samples from 15 populations and cluster II included most samples from the YN population, this supported by the phylogenetic findings showing the YN populations also as an independent clade (Additional file 3: Figure S2). However, three clusters of An. sinensis populations were detected over seven Chinese provinces by mtDNA-ND5 gene. All three clusters were observed in An. sinensis samples collected from different sites demonstrating apparent differences in relative abundance for given clusters [16]. The CI was similar with cluster I, while CII and CIII were added together corresponding to cluster II of this study. But two gene pools grouping An. sinensis samples by microsatellites were difficult to correspond to the two clusters by cox1 in the present study [19].

Anopheles sinenesis population genetic variation detected by the microsatellites and the mtDNA were compared. Firstly, microsatellite results sorted the Chinese An. sinensis populations into two gene pools, six of 14 populations were mixed with individuals from both gene pools, indicating the coexistence of two genetic units in the areas sampled [19]. In this study, 15 populations were divided into two clusters, and almost all individuals in cluster II were from the YN population. Secondly, the level of F ST values in An. sinensis populations from China used by microsatellites showing a range of 0.004−0.048 [19] compared to a range of 0.000−0.452 in this study. Similar the report in ROK, the range of F ST was 0.000−0.110 by microsatellites [51], while 0.000−0.3125 by mtDNA control region [17]. Thirdly, no overall correlation between genetic and geographical distance was detected in populations of An. sinensis in China, both by mtDNA and microsatellites, unlike in ROK [17, 51]. This may be due to China’s wide geographical area, resulting in dilution of the impact imposed by geographical barriers.

In this study, the neutrality test values of Tajima’s D and Fu’s Fs were all negative, which suggensted that An. sinensis population expansion events may have occurred in the demographic history. Moreover, the distribution of pairwise nucleotide differences was characteristic of a population that has undergone a large expansion. Furthermore, small and not statistically significant mismatch analysis statistics SSD and Rag supported the hypothesis of population expansion. These findings were also consistent with previously reported results based on the ND5 gene [16]. These results were supported by many low-frequency mutations in populations and with possible effects of purifying selection, or population expansion of An. sinensis in these locations.

Conclusions

A better understanding of genetic diversity of local An. sinensis and metapopulation dynamics could provide important information for the epidemiological surveillance and malaria vector control strategy. In this study, our collection sites covered most of the distribution in which malaria used to be meso-endemic or hypo-endemic in its regions in China. Anopheles sinensis populations showed high genetic polymorphism by cox1 gene. The weak genetic structure may be a consequence of low genetic differentiation and high gene flow among populations, except in the case of the YN population. The population structure implies that the expansion and spread of genes responsible for immunity against malaria or insecticide resistance would be more probable between the populations. The YN population was isolated from the other populations with its large pairwise F ST value, gene flow limited by geographical distances and barriers, thus forming a separate cluster (cluster II). Anopheles sinensis population size was large owing to the recent expansion of these populations in China.

Additional files

GenBank accession numbers for the Anopheles sinensis haplotypes among populations. (PDF 2557 kb)

Graphs of the mismatch distributions analysis for total populations of Anopheles sinensis using DnaSP 5.10. The X axis shows the observed distribution of pairwise nucleotide differences and the Y axis shows the frequencies. The dotted lines represent the observed frequency of pairwise differences, and the solid lines show the expected values under the sudden population expansion model. (TIF 8 kb)

Phylogenetic tree of Anopheles sinensis populations based on mitochondrial cox1 gene. (TIF 512 kb)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Hongning Zhou (Yunnan), Guangquan Huang and Guoying Chen (Hubei), Jin Wu (Guangdong), Yaming Huang (Guangxi), Yaohua Shi (Guizhou), Peng Li (Henan), Jibo Zhang and Zhe Chen (Liangning), Xixin Chen (Shandong), Xintian Lei (Sichuan), Wei Zhao and Linhai Zeng (Hainan), Jiafang Gao (Jiangsu), Ying Ma (Jiangxi), and Baohai Xu (Fujian), who provided field assistance, mosquito specimens, and valuable information used in the study.

Funding

This work was funded by YM’s grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81371848) and National Natural Science Foundation of China-Yunnan Joint Fund (U0932604). The funding agencies did not play any role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the GenBank repository under accession numbers KX779529−KX779775.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the collection of mosquitoes. YM designed the study. YM identified specimens by morphological characters. XF, LL and MY performed PCR, XF did sequence comparison. XF, LH and YM did data analysis and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the NSFC ethical guidelines for biomedical research involving living animals and human subjects.

Abbreviations

- cox1

Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I

- cox2

Cytochrome c oxidase subunit II

- FST

Fixation index

- ITS2

Internal transcribed spacer 2

- nad5

NADH dehydrogenase subunit 5

- Nm

Gene flow

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- RAPDs

Random amplified polymorphic DNA

- SD

Standard deviation

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13071-017-2013-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13071-017-2048-1.

Contributor Information

Xinyu Feng, Email: fengxinyu2013@163.com.

Libin Huang, Email: 80987670@qq.com.

Lin Lin, Email: linlin198210@tongji.edu.cn.

Manni Yang, Email: yangmanni568@163.com.

Yajun Ma, Email: yajun_ma@163.com.

References

- 1.Lu B. Fauna Sinica, Insecta Vol. 9: Diptera, Culicidae II. Beijing: Science Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou SS, Zhang SS, Wang JJ, Zheng X, Huang F, Li WD, et al. Spatial correlation between malaria cases and water-bodies in Anopheles sinensis dominated areas of Huang-Huai plain, China. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:106. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang SQ, Zhang QJ, Cheng F, Wang LL, Pen GP. Threshold of transmission of Brugia malayi by Anopheles sinensis. J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;94(4):245–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ren Z, Wang D, Hwang J, Bennett A, Sturrock HJ, Ma A, et al. Spatial-temporal variation and primary ecological drivers of Anopheles sinensis human biting rates in malaria epidemic-prone regions of China. PLoS One. 2015;10(1):e0116932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shen Y. Investigation on transmission factors of malaria in Anopheles sinensis areas in Anhui Province. J Pathog Biol. 2006;1(4):301–303. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu T, Liu YB, Zhang SS, Xia ZG, Zhou SS, Yan J, et al. Shrinking the malaria map in China: measuring the progress of the National Malaria Elimination Programme. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s40249-016-0146-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu Y, Zhou G, Ruan Y, Lee MC, Xu X, Deng S, et al. Seasonal dynamics and microgeographical spatial heterogeneity of malaria along the China-Myanmar border. Acta Trop. 2016;157:12–9. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang JX, Xia ZG, Zhou SS, Pu XJ, Hu MG, Huang DC, et al. Spatio-temporal analysis of malaria vectors in national malaria surveillance sites in China. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:146. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-0741-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang D, Li S, Cheng Z, Xiao N, Cotter C, Hwang J, et al. Transmission risk from imported Plasmodium vivax malaria in the China-Myanmar border region. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(10):1861–4. doi: 10.3201/eid2110.150679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bi Y, Yu W, Hu W, Lin H, Guo Y, Zhou XN, et al. Impact of climate variability on Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Yunnan Province, China. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:357. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ma Y, Xu J. The Hyrcanus group of Anopheles (Anopheles) in China (Diptera: Culicidae): species discrimination and phylogenetic relationships inferred by ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer 2 sequences. J Med Entomol. 2005;42(4):610–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma Y, Wang J. Numerical taxonomic study of 5 species and 4 strains of Anopheles hyrcanus group (Diptera: Culicidae) J Guiyang Med Coll. 1990;15(1):45–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baimai V, Rattanarithikul R, Kijchalao U. Metaphase karyotypes of Anopheles of Thailand and Southeast Asia: I. The Hyrcanus group. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 1993;9:59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun Y. The research progress of variation among Anopheles sinensis strains in China. Chin Bull Entomol. 1993;30:56–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Qian H, Tang L, Cheng Y, Yang B. Preliminary estimation of malaria transmission potential in areas where Anopheles sinensis is the only vector. Chin J Parasit Parasitic Dis. 1994;12(4):265–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Makhawi AM, Liu XB, Yang SR, Liu QY. Genetic variations of ND5 gene of mtDNA in populations of Anopheles sinensis (Diptera: Culicidae) malaria vector in China. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:290. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung J, Jung Y, Min G, Kim W. Analysis of the population genetic structure of the malaria vector Anopheles sinensis in South Korea based on mitochondrial sequences. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:310–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma Y, Qu F, Xu J, Zheng Z. Study on molecular genetic polymorphism of Anopheles sinensis populations in China. Acta Entomol Sin. 2001;44:33–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma Y, Yang M, Fan Y, Wu J, Xu J. Population structure of the malaria vector Anopheles sinensis (Diptera: Culicidae) in China: two gene pools inferred by microsatellites. PLoS One. 2011;6 7:e22219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng X, Ma Y, Xu J, Liang J, Xia A. Genetic polymophism and evolution of SRPN14 gene in Anopheles sinensis (Diptera : Culicidae) Chin J Parasit Parasitic Dis. 2015;33(4):241–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang D, Ma Y, Zhou H. Genetic variation of Anopheles dirus A and D (Diptera:Culicidae) in China: inferred by mtDNA-COI gene sequences. Chin J Parasit Parasitic Dis. 2007;25(5):368–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang M, Ma Y. Molecular population genetic structure of Anopheles lesteri (Diptera: Culicidae) based on mtDNA-COI gene sequences. Acta Entomol Sinica. 2009;52(9):1000–7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walton C, Handley JM, Tun-Lin W, Collins FH, Harbach RE, Baimai V, et al. Population structure and population history of Anopheles dirus mosquitoes in Southeast Asia. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17(6):962–74. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutierrez LA, Gomez GF, Gonzalez JJ, Castro MI, Luckhart S, Conn JE, et al. Microgeographic genetic variation of the malaria vector Anopheles darlingi root (Diptera: Culicidae) from Cordoba and Antioquia, Colombia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83(1):38–47. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ali N, Hume JC, Dadzie SK, Donnelly MJ. Molecular genetic studies of Anopheles stephensi in Pakistan. Med Vet Entomol. 2007;21(3):265–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2007.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen B, Harbach RE, Butlin RK. Genetic variation and population structure of the mosquito Anopheles jeyporiensis in southern China. Mol Ecol. 2004;13(10):3051–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang KS, Yoo DH, Ju YR, Lee WG, Roh JY, Kim HC, et al. Distribution of malaria vectors and incidence of vivax malaria at Korean army installations near the demilitarized zone, Republic of Korea. Malar J. 2016;15(1):259. doi: 10.1186/s12936-016-1301-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Avise J. Molecular markers, natural history and evolution. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazooan intertebrates. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol. 1994;3(5):294–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson J, Gibson T, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins D. The ClustalX windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;24:4876–82. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–9. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rozas J, Sánchez-DelBarrio J, Messeguer X, Rozas R. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2496–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bandelt H, Forster P, Röhl A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:37–48. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nei M, Li WH. Mathematical model for studying genetic variation in terms of restriction endonucleases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76(10):5269–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.10.5269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slatkin M. A measure of population subdivision based on microsatellite allele frequencies. Genetics. 1995;139:457–62. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.1.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Slatkin M. Gene flow and the geographic structure of natural populations. Science. 1987;236(4803):787–92. doi: 10.1126/science.3576198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Excoffier L, Lischer H. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: a new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;10:564–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen J, Bohonak A, Kelley S. Isolation by distance, web service. BMC Genet. 2005;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneider S, Excoffier L. Estimation of past demographic parameters from the distribution of pairwise differences when the mutation rates vary among sites: application to human mitochondrial DNA. Genetics. 1999;152(3):1079–89. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.3.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wijit A, Saeung A, Baimai V, Otsuka Y, Thongsahuan S, Taai K, et al. DNA barcoding for the identification of eight species members of the Thai Hyrcanus Group and investigation of their stenogamous behavior. C R Biol. 2013;336(9):449–56. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lopez-Rubio A, Suaza-Vasco J, Marcet PL, Ruiz-Molina N, Caceres L, Porter C, et al. Use of DNA barcoding to distinguish the malaria vector Anopheles neivai in Colombia. Zootaxa. 2016;4175(4):377–89. doi: 10.11646/zootaxa.4175.4.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan A, Chiang LP, Hapuarachchi HC, Tan CH, Pang SC, Lee R, et al. DNA barcoding: complementing morphological identification of mosquito species in Singapore. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:569. doi: 10.1186/s13071-014-0569-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Versteirt V, Nagy ZT, Roelants P, Denis L, Breman FC, Damiens D, et al. Identification of Belgian mosquito species (Diptera: Culicidae) by DNA barcoding. Mol Ecol Resour. 2015;15(2):449–57. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruiz-Lopez F, Wilkerson RC, Conn JE, McKeon SN, Levin DM, Quinones ML, et al. DNA barcoding reveals both known and novel taxa in the Albitarsis Group (Anopheles: Nyssorhynchus) of Neotropical malaria vectors. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:44. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang M, Ma Y, Wu J. Mitochondrial genetic differentiation across populations of the malaria vector Anopheles lesteri from China (Diptera: Culicidae) Malar J. 2011;10:216. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chang X, Zhong D, Lo E, Fang Q, Bonizzoni M, Wang X, et al. Landscape genetic structure and evolutionary genetics of insecticide resistance gene mutations in Anopheles sinensis. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:228. doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1513-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang Y, Yu W, Shi H, Yang Z, Xu J, Ma Y. Historical survey of the kdr mutations in the populations of Anopheles sinensis in China in 1996–2014. Malar J. 2015;14:120. doi: 10.1186/s12936-015-0644-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu H, Xu Z, Wang H, Li B. Tropical rain forest fragmentation and its ecological and species diversity changes in southern Yunnan. Biol Conserv. 2004;13:1355–72. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dong X, Zhou H, Gong Z, Dong L, Wang X. Investigation of mosquito species in Yunnan Province with some new species. Chin J Vector Biol Control. 2004;5:186–8. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhong D, Chang X, Zhou G, He Z, Fu F, Yan Z, et al. Relationship between knockdown resistance, metabolic detoxification and organismal resistance to pyrethroids in Anopheles sinensis. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kang S, Jung J, Kim W. Population genetic structure of the malaria vector Anopheles sinensis (Diptera: Culicidae) sensu stricto and evidence for possible introgression in the Republic of Korea. J Med Entomol. 2015;52(6):1270–81. doi: 10.1093/jme/tjv114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

GenBank accession numbers for the Anopheles sinensis haplotypes among populations. (PDF 2557 kb)

Graphs of the mismatch distributions analysis for total populations of Anopheles sinensis using DnaSP 5.10. The X axis shows the observed distribution of pairwise nucleotide differences and the Y axis shows the frequencies. The dotted lines represent the observed frequency of pairwise differences, and the solid lines show the expected values under the sudden population expansion model. (TIF 8 kb)

Phylogenetic tree of Anopheles sinensis populations based on mitochondrial cox1 gene. (TIF 512 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available in the GenBank repository under accession numbers KX779529−KX779775.