Abstract

Gastric cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide. Despite progress in understanding its development, challenges with treatment remain. Gastrin, a peptide hormone, is trophic for normal gastrointestinal epithelium. Gastrin also has been shown to play an important role in the stimulation of growth of several gastrointestinal cancers including gastric cancer. We sought to review the role of gastrin and its pathway in gastric cancer and its potential as a therapeutic target in the management of gastric cancer. In the normal adult stomach, gastrin is synthesized in the G cells of the antrum; however, gastrin expression also is found in many gastric adenocarcinomas of the stomach corpus. Gastrin’s actions are mediated through the G-protein–coupled receptor cholecystokinin-B (CCK-B) on parietal and enterochromaffin cells of the gastric body. Gastrin blood levels are increased in subjects with type A atrophic gastritis and in those taking high doses of daily proton pump inhibitors for acid reflux disease. In experimental models, proton pump inhibitor–induced hypergastrinemia and infection with Helicobacter pylori increase the risk of gastric cancer. Understanding the gastrin:CCK-B signaling pathway has led to therapeutic strategies to treat gastric cancer by either targeting the CCK-B receptor with small-molecule antagonists or targeting the peptide with immune-based therapies. In this review, we discuss the role of gastrin in gastric adenocarcinoma, and strategies to block its effects to treat those with unresectable gastric cancer.

Keywords: G17DT, CCK-B Receptor, Proton Pump Inhibitors, PPIs

Abbreviations used in this paper: CCK-BR, cholecystokinin-B receptor; ECL, enterochromaffin-like; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; ERK, extracellular signal–regulated kinase; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; IHC, immunohistochemistry; PAS, polyclonal antibody stimulator; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas

Summary.

The gastrointestinal peptide, gastrin, stimulates growth of gastric adenocarcinoma (gastric cancer) through the cholecystokinin-B receptors that are overexpressed in this malignancy. Serum gastrin levels may be increased secondary to chronic administration of proton pump inhibitors, atrophic gastritis, Helicobacter pylori infection, or from de novo gastrin expression from the gastric cancer epithelial cells. Strategies to interrupt the interaction of gastrin at the cholecystokinin-B receptor may provide a novel approach to the treatment of gastric cancer.

Gastric adenocarcinoma (gastric cancer) is a common malignancy and is the world’s second leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide.1 Novel therapeutic targets desperately are needed. The meager improvement in the approximately 10% cure rate realized by adjunctive treatments to surgery is unacceptable because more than 50% of patients with localized gastric cancer die as a result of their disease.2 The prognosis of those with advanced gastric cancer is poor, with a 5-year survival of only 20%–30%.3, 4 The only curative option in the treatment of gastric cancer is surgery, and for metastatic disease conventional chemotherapy has shown only a modest benefit, with an average survival of approximately 10 months.5 Unfortunately, however only marginal improvements in patient outcomes have been achieved with chemotherapy despite extensive phase 3 testing.6 The current standard of care for advanced gastric cancer in the first-line setting remains a combination of a fluoropyrimidine (eg, 5-fluorouracil) and a platinum (eg, cis-platinum)-containing chemotherapeutic agent. Targeted therapy may offer new possibilities for the treatment of gastric cancer. Because human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) receptors are found in approximately 20% of gastric cancers, the addition of a HER2-receptor antibody to standard chemotherapy may be beneficial, as shown in the Trastuzumab for Gastric Cancer study, in which trastuzumab (Herceptin; Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) was beneficial in subjects with HER2-positive gastric cancer.7 However, clinical trials studying the value of other targeted therapies, such as with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or vascular endothelial growth factor, yielded disappointing results.8, 9

Histologic and Molecular Classifications of Gastric Cancer

In the West, most of those with gastric cancer typically present with advanced or metastatic disease, whereas in several Asian countries, gastric cancer usually is identified early and cure rates are higher.10 Other regional differences in gastric cancer are readily identifiable; for example, proximal gastric cancers are more prevalent in Europe and the Americas than in Asia.11 Histologically, gastric cancer has been categorized according to the Lauren12 classification as either diffuse or intestinal-type. The intestinal-type is characterized by chronic Helicobacter pylori infection; is more prevalent in high-incidence areas such as Japan, Korea, and Eastern Europe13; and the more aggressive diffuse type has been associated with genetic variations (single nucleotide polymorphisms) of the prostate stem cell antigen.14 The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Research Network described 4 groups of gastric cancer based on molecular classifications including Epstein–Barr virus, microsatellite instability, genomically stable, and chromosomal instability.15 With the TCGA classification, 73% of the genomically stable were the diffuse type histologically according to Lauren’s criteria and systematic differences in distribution were not observed between East Asian and those of Western origin. The Asian Cancer Research Group16 further characterized the molecular classification with the incorporation of the tumor protein 53 activity and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and found some unique differences compared with the TCGA analysis.

Risk Factors for Gastric Cancer

Factors associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer include nutrition, such as high salt and nitrate intake, a diet low in vitamins A and C, the consumption of large amounts of smoked or cured foods, lack of refrigerated foods, and poor-quality drinking water.17 Occupational exposure to rubber and coal also increase the risk.18 Other risk factors that have been implicated include the following: cigarette smoking, H pylori infection, Epstein–Barr virus, radiation exposure, and prior gastric surgery for benign ulcer disease.18 More recently, a number of investigators have shown that polymorphisms in inflammatory genes can be associated with gastric cancer risk.19, 20 Genetic risk factors include type A blood group, pernicious anemia, family history of gastric cancer, hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer, and Li–Fraumeni syndrome.18 Most cases of gastric cancer are sporadic, and gastric cancer associated with an inherited syndrome occurs in only a limited number of patients (1%–3%). E-cadherin mutations occur in approximately 25% of families with an autosomal-dominant hereditary form of diffuse gastric cancer.21

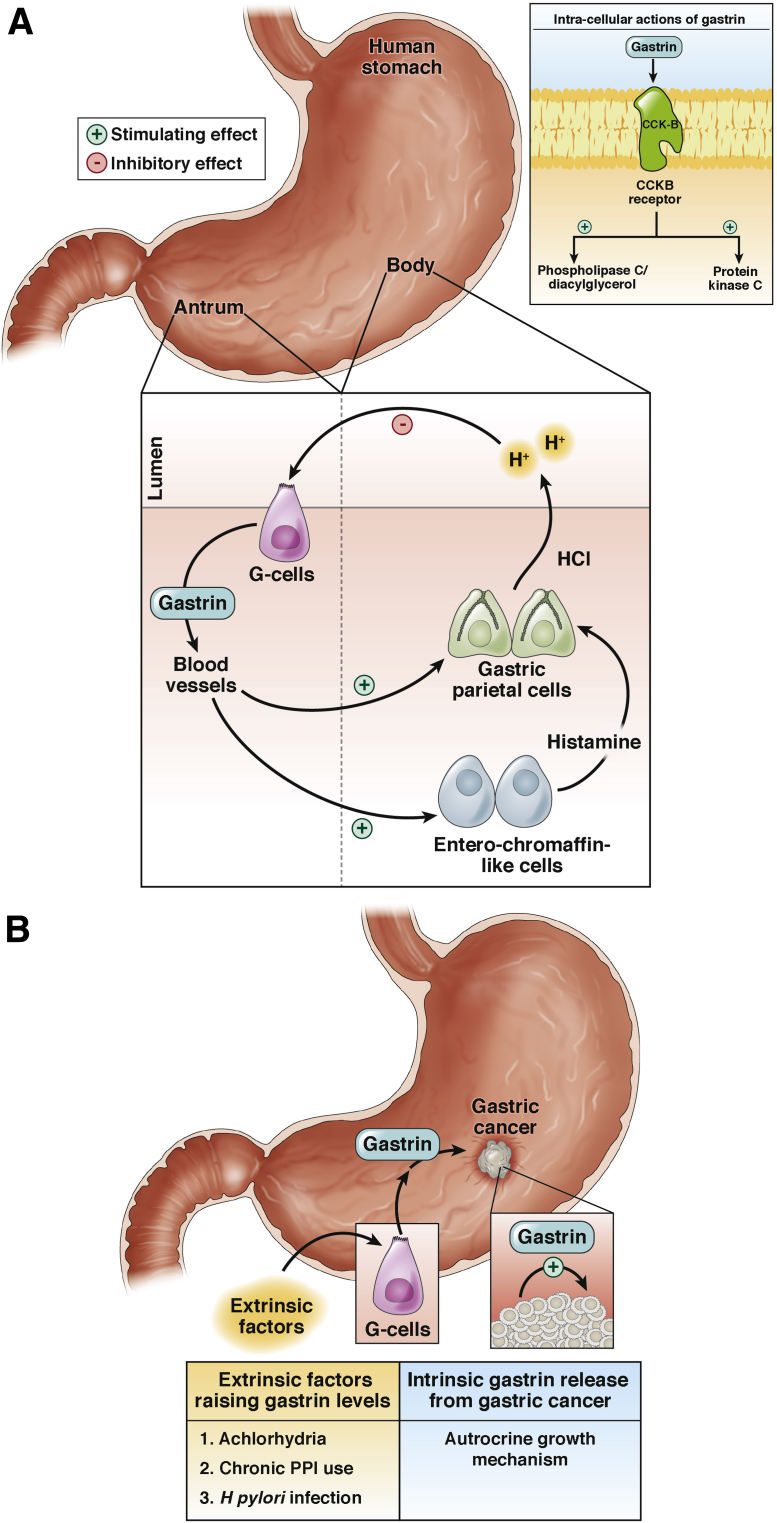

The gastrointestinal peptide gastrin is involved physiologically in secretion of gastric acid22 and growth of the gastrointestinal tract.23 Gastrin is an important growth factor for the developing24 and adult25 digestive system, and is trophic to the entire gastrointestinal tract.26, 27 Gastrin is released from G cells in the stomach antrum during normal physiologic digestion of food and serves as a major stimulator of gastric acid secretion from the stomach parietal cells (Figure 1).28 In human beings the majority of gastrins are amidated and gastrin-17 is the most abundant circulating gastrin in the peripheral blood.29 Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been developed to facilitate healing of peptic ulcer disease and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Because this class of medications is very effective in suppressing acid, a consequence of long-term acid suppression can be the increase of serum gastrin levels30, 31 resulting from the interruption of the normal feedback mechanisms. One PPI, omeprazole, causes a 2- to 6-fold increase in serum gastrin levels in 80%–100% of patients receiving chronic therapy.30, 32, 33 Up to 30% of patients on chronic PPI therapy may have gastrin blood levels greater than 500 ng/L or more than 6-fold greater than the upper limit of normal.30, 31, 33 Even short-term administration of omeprazole has been shown to increase serum gastrin levels,34 however, levels return to normal after discontinuation. Although raised as a potential issue at the time of their initial approval 25 years ago, the concern regarding PPI-induced hypergastrinemia has not disappeared completely.35, 36

Figure 1.

Physiologic and pathologic role of gastrin. (A) Under physiologic conditions gastrin is released from antrum G cells in response to food, decreased acid, and gastric distension. Gastrin circulates in the peripheral blood and binds to the CCK-B receptors on the parietal and ECL cells of the body. The ECL cells release histamine, which activates the H2 receptors on parietal cells and HCl (H+) is released. The increased H+ feeds back to the D cells of the antrum to release somatostatin to turn off the gastrin release. Gastrin also is responsible for basal growth and renewal of the gastric epithelium. Normal signaling through the CCK-B receptor occurs through the activation of the phospholipase C-β/diacylglycerol/Ca2+/protein kinase C. (B) Increased gastrin levels can result from achlorhydria, chronic use of PPIs, or H pylori infection. Gastric cancer epithelial cells that express CCK-B receptors also produce their own gastrin de novo, which in turn stimulates growth and metastases of gastric cancer by an autocrine mechanism.

One concern in regard to hypergastrinemia and PPIs has been the potential relationship between gastrin and gastric cancer. When gastrin is administered in animal models, there is a marked increase in parietal cell mass and the enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells of the stomach body.37 Increased gastrin levels in rats38 and human beings39 have been associated with gastric carcinoid tumors arising from the ECL cells. In cell culture, gastrin has been shown to stimulate the growth of human gastric cancer cell lines.40, 41 Several reviews and meta-analyses have been performed concerning the association between PPI use and risk for gastrointestinal cancers without confirmatory results.42, 43 Ahn et al44 reported a significantly increased risk of gastric cancer in a large systematic search with a cohort of nearly 6000 subjects; however, Lundell et al45 did not find an increased risk in a cohort of 1920 subjects. Han et al46 even suggested that PPI use may decrease the risk of gastric cancer by antagonizing the proliferative and anti-apoptotic effects of gastrin.46

Gastrin Mediates its Effects Through the Cholecystokinin-B Receptor

Gastrin mediates both its acid-releasing and growth properties on the gastrointestinal tract through a G-protein–coupled receptor called the cholecystokinin (CCK) or CCK-B receptor (CCK-BR).47 After interacting with the CCK-BR on parietal or ECL-like cells, downstream signaling occurs through the activation of the phospholipase C–β/diacylglycerol/Ca2+/protein kinase C cascade48 (Figure 1). CCK-B receptors are overexpressed in gastric cancers,40, 49 and stimulation with exogenous gastrin promotes growth of this malignancy.40 CCK receptors also induce other signaling pathways through tyrosine kinase receptors. CCK-BR signaling also has been shown to transactivate the EGFR50 through Src and Matrix metalloproteinase releasing transforming growth factor-α from its precursor protein causing EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation.50 The EGFR phosphorylates phosphoinositide 3-kinase, activating PDK1, Protein kinase B (PKB), and mammalian target of rapamycin. The EGFR interacts with adaptor proteins Grb2 and SOS, activating Ras and Raf, followed by phosphorylation of Mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK and extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK). Gastrin also has been shown to mediate its actions by up-regulating phosphorylation of ERK and K-Ras through the Ras-Raf-MEK1/2-ERK1/2 pathway.51, 52 Gastrin also has been shown to induce other EGFR ligands such as heparin-binding EGF,53, 54, 55 as well as trefoil family factor 2 expression.56, 57 The end result of CCK-BR signaling involves motility,58 secretion,59 and migration,60 as well as growth and proliferation.26 In addition, gastrin has shown angiogenesis and anti-apoptotic characteristics in several malignancies including gastric cancer.61, 62, 63

Expression of Gastrin and the CCK-B Receptors in Gastric Cancer and Stem Cells

Unlike the normal expression of gastrin in G cells of the stomach,64 the gastrin gene also becomes overexpressed de novo in nonendocrine epithelial cells of gastric cancer65 and, likewise, the CCK-B receptor becomes overexpressed in cancer cells.40 The mechanisms involved with gastrin gene activation or gastrin peptide re-expression are unknown, however, several mechanisms have been proposed. EGFR ligands have been shown to induce gastrin gene transcription in a human gastric cancer cell line, through an EGF response element that has been mapped to the gastrin promoter.66 The gastrin promoter activation is mediated in part by the Ras–Erk signaling cascade that targets Sp1, a zinc finger transcription factor that is involved in regulating expression of a large number of genes that contribute to the “hallmarks of cancer.”67 Goetze et al68 analyzed 20 resected human gastric cancers and found that all expressed CCK-B receptors and gastrin messenger RNA by real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. They confirmed gastrin peptide expression in 16 of 20 gastric cancers by Western blot analysis and immunohistochemistry (IHC). Henwood69 examined 90 archival tissue samples of gastrin cancer and also identified the de novo presence of gastrin peptide by IHC. Hur et al70 examined 279 human gastric cancers and found gastrin peptide expression by IHC in 47.7% and the CCK-B receptor in 56.6%; the CCK-B receptor detection was significantly greater in tumors characterized as intestinal-type by the Lauren12 classification. Hypergastrinemia in animal models has been shown to promote gastric carcinogenesis of proximal gastric tumors,71 whereas deficiency of gastrin (ie, in gastrin knock-out mice) has been associated with antral tumors.72 An explanation for these dissimilarities may be related to gastrin’s actions on the stem cells in the antrum compared with the corpus. Through lineage tracing experiments, Hayakawa et al73, 74 reported that the CCK-B receptor expression in the stomach antrum is expressed in position 4+ of antral stem cells and responds to progastrin rather than gastrin-17. In the gastric cardia CCK-B receptors are found on position 4+ stem cells, but unlike the antral stem cells these cells respond to the proliferative actions of amidated gastrin-17.74, 75 In the body of the stomach, the CCK-B receptors on the parietal cells, ECL cells, and cells in the isthmus also respond to gastrin-17.48, 75, 76

There is a well-known association between H pylori infection and gastric cancer.77, 78 Although many investigators had thought that the mechanism solely due to chronic inflammation induced by H pylori, studies now have shown that H pylori also induces genetic and epigenetic changes that lead to genetic instability in gastric epithelial cells.79 Cover80 recently described strain differences in H pylori in regard to the presence or absence of a 40-kb chromosomal region known as the cag pathogenicity island. Current evidence suggests that the risk of gastric cancer is very low among persons harboring H pylori strains that lack the cag pathogenicity island. A relationship between gastrin and H pylori infections has shown that gastrin messenger RNA is up-regulated by H pylori–cytotoxin–associated protein A.81 Beales and Calam82 showed that infection of canine G cells with H pylori increased endogenous gastrin secretion from the G cells by 17%–27%. In addition, patients with asymptomatic H pylori infection were found to have increased gastrin levels by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.83

Although hypergastrinemia is associated with the development of gastric neuroendocrine tumors and gastric adenocarcinoma,84 both animal and human studies have shown the greater incidence of gastric carcinoids in patients with increased gastrin levels. One possible explanation for the more frequent neuroendocrine tumors over gastric adenocarcinoma in patients with hypergastrinemia may be related to the finding that although the CCK-B receptor is present on parietal cells, it is expressed more abundantly in ECL cells of the stomach.85, 86 In addition to responding to the proliferative effects of gastrin, studies also have shown that the parietal cells respond to other trophic factors secreted by the ECL-like cells by a paracrine mechanism including secretion of Reg protein,87 heparin-binding EGF,88 and even histamine.89 With more sophisticated technology using lineage tracing, researchers have confirmed the presence of CCK-B receptors on the antrum stem cells that do not respond to gastrin-17.73 These studies also help us understand that hypergastrinemia selectively increases the risk of gastric corpus cancers and low gastrin levels may increase the risk for antral cancers. Whether hypergastrinemia enhances the growth of gastric carcinoids more frequently than gastric adenocarcinoma seems irrelevant when the long-term prognosis differs between these 2 lesions, with adenocarcinoma doing more poorly. Clinical investigations in human subjects also have shown that hypergastrinemia adversely affects survival from subjects with stages 2–4 gastric adenocarcinomas.90 Therefore, strategies to decrease gastrin levels in subjects with gastric cancers may be useful.

Gastrin-CCK-B Receptor Pathway

Treatment of cancer is improved significantly when a cancer-specific target or cell surface receptor is identified. Because gastrin has been shown to stimulate growth of gastric cancer and other gastrointestinal malignancies, researchers have been studying means to block the ligand:receptor interaction in an attempt to slow or arrest tumor growth. Numerous investigations have been conducted in cell culture and animal models of gastric cancer using small-molecule CCK-B receptor antagonists,91, 92 and their use in human trials has been reviewed.76, 93, 94

Clinical trials in human subjects with agents directed to the gastrin:CCK-B–receptor pathway are rare and most studies have investigated agents in other gastrointestinal cancers rather than in gastric cancer, such as gastrazole in pancreatic cancer95 or netazepide96 in gastric neuroendocrine tumors.

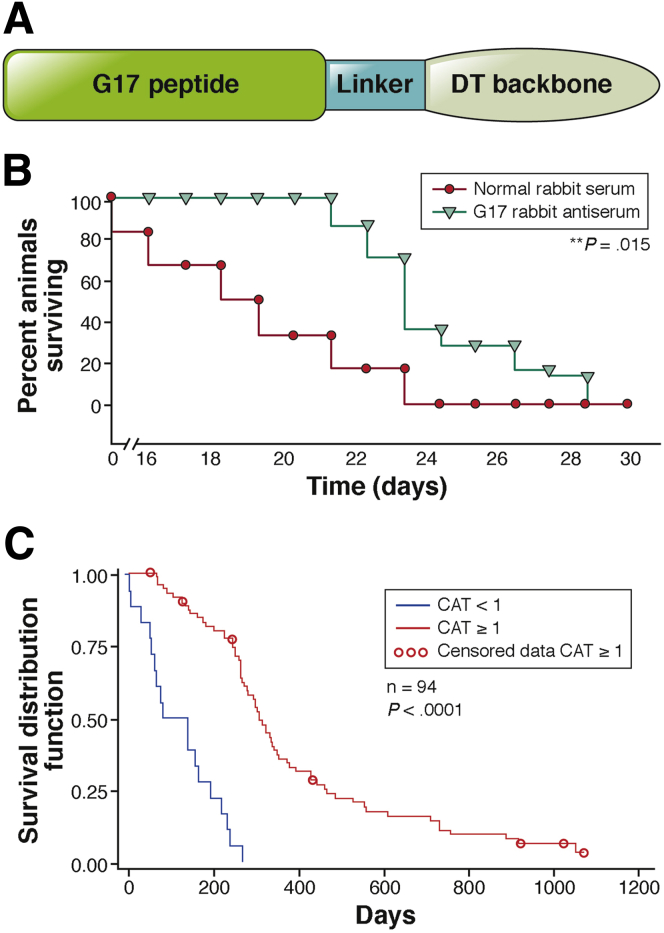

Polyclonal antibody stimulator (PAS), formerly called G17DT and gastrimmune, was developed as an immunogen containing a 9–amino acid epitope derived from the amino-terminal sequence of gastrin-17 conjugated to diphtheria toxoid (Figure 2A). PAS elicits specific and high-affinity antibodies that bind gastrin-17 and gly-gastrin, thus preventing its trophic activity. Unlike tumor-associated antigen-based vaccines, PAS is unique in that it produces neutralizing antibodies to gastrin with peak titers occurring by week 6 and persisting after vaccination for up to 40 weeks. Preclinical studies were performed in several animal models that have CCK-B receptors,97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104 including gastric cancer.40, 41 In these animal models, PAS-generated anti-G17 antibodies have been shown to reduce growth and metastases.105, 106, 107 Passive immunization with PAS antibodies raised in rabbits improved survival of severe combined immunodeficiency disease mice bearing gastric cancers compared with diluent-treated controls108 (Figure 2B). To date, 5 open-labeled clinical trials have been conducted using PAS in subjects with gastric cancer in doses ranging from 10 to 500 μg intramuscularly (Table 1).109, 110 One gastric cancer study, GC2,110 was a dose-finding study and tested 3 doses and analyzed response according to stage of disease. Only 1 study, GC4, evaluated the safety and survival of PAS in combination with standard chemotherapy.109 The median survival of those with advanced gastric cancer after PAS administration was prolonged significantly (10.8 mo) in subjects who mounted a circulating antibody titer against gastrin (ie, responders) compared with subjects who failed to generate an antibody response (6.2 mo) (ie, nonresponders) (Figure 2C). The only notable PAS-related adverse events when compared with placebo were injection-site reaction and pyrexia.

Figure 2.

Polyclonal antibody stimulator. (A) Diagram showing the structure of PAS with the gastrin epitope linked to diphtheria toxoid with a peptide spacer. Characteristics include a molecular weight of 84 kilodaltons; an appearance that is clear, colorless, to slightly yellow solution; and a pH of 7.0–7.4. PAS is water-soluble and administered as an intramuscular injection. (B) Treatment of severe combined immunodeficiency disease mice with gastric cancer showed greater survival compared with mice treated with nonimmune antibody. **P = .015.107 (C) Human subjects with gastric cancer treated with PAS vaccination that elicit circulating antibody titers (CAT) have a significantly prolonged survival when compared with subjects who do not elicit an antibody response (P < .0001). (Adapted with permission from Ajani JA, Hecht JR, Ho L, et al. An open-label, multinational, multicenter study of G17DT vaccination combined with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil in patients with untreated, advanced gastric or gastroesophageal cancer: The GC4 study. Cancer 2006;106:1908–1916).

Table 1.

Summary of Clinical Trials With PAS in Gastric Cancer

| Study name | Study design | Subjects, n | Dose(s), mcg | Schedule, wk | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC2110 | Open-label, dose ranging | 52 | 10, 100, 250 | 0, 2, 6 | 250 μg gave a 92% Ab response |

| GC3 | Open-label, dose ranging | 33 | 100, 250, 500 | 0, 1, 3 | Dosing schedule was poorly tolerated |

| GC4109 | Open-label, combination of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil in chemotherapy-naive subjects, safety and survival study | 103 | 500 | 1, 5, 9, 25 | 67% Ab titers Survival Ab responders 10.3 mo |

| GC5 | Open-label | 7 | 500 | 0, 2, 6 | Stopped prematurely because of poor tolerability |

| GC12 | Open, dosing study | 40 | 125, 250 | 0, 2, 6 | 85% Ab response, 250 μg was more effective than 125 μg |

Ab, antibody; GC, gastric cancer.

Conclusions

Survival from advanced gastric cancer is poor and new strategies are needed for therapy. CCK-B receptors are overexpressed in many gastric cancers and when these receptors are activated by gastrin, the result is tumor proliferation. Furthermore, many gastric cancers also express gastrin, which stimulates cancer growth by an autocrine mechanism. Understanding the mechanisms and receptor-mediated pathways that regulate the growth of gastric cancer is important. Novel therapeutic agents that target the gastrin:CCK-B–receptor pathways are promising and may help improve survival of advanced gastric cancer.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest These authors disclose the following: Nick Osborne is employed by Cato Research, a company that owns the rights to the polyclonal antibody stimulator; and Jill Smith serves as a consultant to Cato Research. The remaining author discloses no conflicts.

References

- 1.Siegel R., Ma J., Zou Z. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elimova E., Shiozaki H., Wadhwa R. Medical management of gastric cancer: a 2014 update. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13637–13647. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i38.13637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J., Steliarova-Foucher E., Lortet-Tieulent J. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1374–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Howlader N., Ries L.A., Stinchcomb D.G. The impact of underreported Veterans Affairs data on national cancer statistics: analysis using population-based SEER registries. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:533–536. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner A.D., Unverzagt S., Grothe W. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3:CD004064. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004064.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohtsu A., Shah M.A., Van C.E. Bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line therapy in advanced gastric cancer: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3968–3976. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bang Y.J., Van C.E., Feyereislova A. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:687–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61121-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuchs C.S., Tomasek J., Yong C.J. Ramucirumab monotherapy for previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (REGARD): an international, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:31–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61719-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lordick F., Kang Y.K., Chung H.C. Capecitabine and cisplatin with or without cetuximab for patients with previously untreated advanced gastric cancer (EXPAND): a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:490–499. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohtsu A., Yoshida S., Saijo N. Disparities in gastric cancer chemotherapy between the East and West. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2188–2196. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.9758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strong V.E., Song K.Y., Park C.H. Comparison of gastric cancer survival following R0 resection in the United States and Korea using an internationally validated nomogram. Ann Surg. 2010;251:640–646. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d3d29b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49. doi: 10.1111/apm.1965.64.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crew K.D., Neugut A.I. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:354–362. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i3.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakamoto H., Yoshimura K., Saeki N. Genetic variation in PSCA is associated with susceptibility to diffuse-type gastric cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40:730–740. doi: 10.1038/ng.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Comprehensive molecular characterization of gastric adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;513:202–209. doi: 10.1038/nature13480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cristescu R., Lee J., Nebozhyn M. Molecular analysis of gastric cancer identifies subtypes associated with distinct clinical outcomes. Nat Med. 2015;21:449–456. doi: 10.1038/nm.3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu C., Russell R.M. Nutrition and gastric cancer risk: an update. Nutr Rev. 2008;66:237–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guggenheim D.E., Shah M.A. Gastric cancer epidemiology and risk factors. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:230–236. doi: 10.1002/jso.23262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li M., Huang L., Qiu H. Helicobacter pylori infection synergizes with three inflammation-related genetic variants in the GWASs to increase risk of gastric cancer in a Chinese population. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen Y.Y., Pan X.F., Loh M. Association of the IL-1B +3954 C/T polymorphism with the risk of gastric cancer in a population in Western China. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2014;23:35–42. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e3283656380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzgerald R.C., Caldas C. Clinical implications of E-cadherin associated hereditary diffuse gastric cancer. Gut. 2004;53:775–778. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.022061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soll A.H., Berglindh T. Receptors that regulate gastric acid-secretory function. In: Johnson L.R., editor. Raven Press; New York: 1994. pp. 1139–1170. (Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. Vol 1. 3rd ed). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dembinski A.B., Johnson L.R. Stimulation of pancreatic growth by secretin, caerulein, and pentagastrin. Endocrinology. 1980;106:323–328. doi: 10.1210/endo-106-1-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Majumdar A.P., Johnson L.R. Gastric mucosal cell proliferation during development in rats and effects of pentagastrin. Am J Physiol. 1982;242:G135–G139. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1982.242.2.G135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hakanson R., Sundler F. Trophic effects of gastrin. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1991;180:130–136. doi: 10.3109/00365529109093190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson L.R., McCormack S.A. Regulation of gastrointestinal mucosal growth. In: Johnson L.R., editor. Raven Press; New York: 1994. pp. 611–642. (Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. Vol 1. 3rd ed). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koh T.J., Chen D. Gastrin as a growth factor in the gastrointestinal tract. Regul Pept. 2000;93:37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(00)00176-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Forte J.G., Wolsin J.M. HCl secretion by the gastric oxyntic cell. In: Johnson L., editor. Raven; New York: 1987. pp. 853–863. (Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schubert M.L. Gastric secretion. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2011;27:536–542. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32834bd53f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koop H., Klein M., Arnold R. Serum gastrin levels during long-term omeprazole treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1990;4:131–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1990.tb00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamberts R., Creutzfeldt W., Struber H.G. Long-term omeprazole therapy in peptic ulcer disease: gastrin, endocrine cell growth, and gastritis. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1356–1370. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90344-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunner G., Creutzfeldt W. Omeprazole in the long-term management of patients with acid-related diseases resistant to ranitidine. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;166:101–105. doi: 10.3109/00365528909091254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jansen J.B., Klinkenberg-Knol E.C., Meuwissen S.G. Effect of long-term treatment with omeprazole on serum gastrin and serum group A and C pepsinogens in patients with reflux esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:621–628. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90946-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lazzaroni M., Sangaletti O., Bianchi P.G. Gastric acid secretion and plasma gastrin during short-term treatment with omeprazole and ranitidine in duodenal ulcer patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 1992;39:366–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chubineh S., Birk J. Proton pump inhibitors: the good, the bad, and the unwanted. South Med J. 2012;105:613–618. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31826efbea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilhelm S.M., Rjater R.G., Kale-Pradhan P.B. Perils and pitfalls of long-term effects of proton pump inhibitors. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2013;6:443–451. doi: 10.1586/17512433.2013.811206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walsh J.H. Role of gastrin as a trophic hormone. Digestion. 1990;47(Suppl 1):11–16. doi: 10.1159/000200509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen D., Zhao C.M., Lindstrom E. Rat stomach ECL cells up-date of biology and physiology. Gen Pharmacol. 1999;32:413–422. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(98)00221-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abraham S.C., Carney J.A., Ooi A. Achlorhydria, parietal cell hyperplasia, and multiple gastric carcinoids: a new disorder. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:969–975. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000163363.86099.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith J.P., Shih A.H., Wotring M.G. Characterization of CCK-B/gastrin-like receptors in human gastric carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 1998;12:411–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watson S., Durrant L., Morris D. Gastrin: growth enhancing effects on human gastric and colonic tumor cells. Br J Cancer. 1989;59:554–558. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1989.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mouli V.P., Ahuja V. Proton pump inhibitors: concerns over prolonged use. Trop Gastroenterol. 2011;32:175–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orlando L.A., Lenard L., Orlando R.C. Chronic hypergastrinemia: causes and consequences. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:2482–2489. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9419-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahn J.S., Eom C.S., Jeon C.Y. Acid suppressive drugs and gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2560–2568. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i16.2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lundell L., Vieth M., Gibson F. Systematic review: the effects of long-term proton pump inhibitor use on serum gastrin levels and gastric histology. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:649–663. doi: 10.1111/apt.13324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han Y.M., Park J.M., Kangwan N. Role of proton pump inhibitors in preventing hypergastrinemia-associated carcinogenesis and in antagonizing the trophic effect of gastrin. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2015;66:159–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dockray G.J., Moore A., Varro A. Gastrin receptor pharmacology. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14:453–459. doi: 10.1007/s11894-012-0293-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dufresne M., Seva C., Fourmy D. Cholecystokinin and gastrin receptors. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:805–847. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00014.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McWilliams D.F., Watson S.A., Crosbee D.M. Coexpression of gastrin and gastrin receptors (CCK-B and delta CCK-B) in gastrointestinal tumour cell lines. Gut. 1998;42:795–798. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.6.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith J.P., Fonkoua L.K., Moody T.W. The role of gastrin and CCK receptors in pancreatic cancer and other malignancies. Int J Biol Sci. 2016;12:283–291. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.14952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cramer T., Juttner S., Plath T. Gastrin transactivates the chromogranin A gene through MEK-1/ERK- and PKC-dependent phosphorylation of Sp1 and CREB. Cell Signal. 2008;20:60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hocker M. Molecular mechanisms of gastrin-dependent gene regulation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1014:97–109. doi: 10.1196/annals.1294.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miyazaki Y., Shinomura Y., Tsutsui S. Gastrin induces heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor in rat gastric epithelial cells transfected with gastrin receptor. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:78–89. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dickson J.H., Grabowska A., El-Zaatari M. Helicobacter pylori can induce heparin-binding epidermal growth factor expression via gastrin and its receptor. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7524–7531. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sinclair N.F., Ai W., Raychowdhury R. Gastrin regulates the heparin-binding epidermal-like growth factor promoter via a PKC/EGFR-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G992–G999. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00206.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Quante M., Marrache F., Goldenring J.R. TFF2 mRNA transcript expression marks a gland progenitor cell of the gastric oxyntic mucosa. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:2018–2027. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tu S., Chi A.L., Lim S. Gastrin regulates the TFF2 promoter through gastrin-responsive cis-acting elements and multiple signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G1726–G1737. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00348.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bierkamp C., Kowalski-Chauvel A., Dehez S. Gastrin mediated cholecystokinin-2 receptor activation induces loss of cell adhesion and scattering in epithelial MDCK cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:7656–7670. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schubert M.L. Functional anatomy and physiology of gastric secretion. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2015;31:479–485. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chang M., Xiao L., Shulkes A. Zinc ions mediate gastrin expression, proliferation, and migration downstream of the cholecystokinin-2 receptor. Endocrinology. 2016;157:4706–4719. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ferrand A., Wang T.C. Gastrin and cancer: a review. Cancer Lett. 2006;238:15–29. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fino K.K., Matters G.L., McGovern C.O. Downregulation of the CCK-B receptor in pancreatic cancer cells blocks proliferation and promotes apoptosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G1244–G1252. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00460.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Grabowska A.M., Watson S.A. Role of gastrin peptides in carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2007;257:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Watson S.A., Grabowska A.M., El-Zaatari M. Gastrin - active participant or bystander in gastric carcinogenesis? Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:936–946. doi: 10.1038/nrc2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Remy-Heintz N., Perrier-Meissonnier S., Nonotte I. Evidence for autocrine growth stimulation by a gastrin/CCK-like peptide of the gastric cancer HGT-1 cell line. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1993;93:23–29. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(93)90135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Merchant J.L., Du M., Todisco A. Sp1 phosphorylation by Erk 2 stimulates DNA binding. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;254:454–461. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Beishline K., Azizkhan-Clifford J. Sp1 and the 'hallmarks of cancer'. FEBS J. 2015;282:224–258. doi: 10.1111/febs.13148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goetze J.P., Eiland S., Svendsen L.B. Characterization of gastrins and their receptor in solid human gastric adenocarcinomas. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:688–695. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.783101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Henwood M., Clarke P.A., Smith A.M. Expression of gastrin in developing gastric adenocarcinoma. Br J Surg. 2001;88:564–568. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2001.01716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hur K., Kwak M.K., Lee H.J. Expression of gastrin and its receptor in human gastric cancer tissues. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2006;132:85–91. doi: 10.1007/s00432-005-0043-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fossmark R., Rao S., Mjones P. PAI-1 deficiency increases the trophic effects of hypergastrinemia in the gastric corpus mucosa. Peptides. 2016;79:83–94. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2016.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zavros Y., Eaton K.A., Kang W. Chronic gastritis in the hypochlorhydric gastrin-deficient mouse progresses to adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2005;24:2354–2366. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hayakawa Y., Jin G., Wang H. CCK2R identifies and regulates gastric antral stem cell states and carcinogenesis. Gut. 2015;64:544–553. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hayakawa Y., Sethi N., Sepulveda A.R. Oesophageal adenocarcinoma and gastric cancer: should we mind the gap? Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:305–318. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hayakawa Y., Chang W., Jin G. Gastrin and upper GI cancers. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2016;31:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2016.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Baldwin G.S., Shulkes A. CCK receptors and cancer. Curr Top Med Chem. 2007;7:1232–1238. doi: 10.2174/156802607780960492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Uemura N., Okamoto S., Yamamoto S. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Waldum H.L., Hauso O., Sordal O.F. Gastrin may mediate the carcinogenic effect of Helicobacter pylori infection of the stomach. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:1522–1527. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Graham D.Y. Helicobacter pylori update: gastric cancer, reliable therapy, and possible benefits. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:719–731. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cover T.L. Helicobacter pylori diversity and gastric cancer risk. MBio. 2016;7 doi: 10.1128/mBio.01869-15. e01869–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhou J., Xie Y., Zhao Y. Human gastrin mRNA expression up-regulated by Helicobacter pylori CagA through MEK/ERK and JAK2-signaling pathways in gastric cancer cells. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:322–331. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Beales I.L., Calam J. Helicobacter pylori increases gastrin release from cultured canine antral G-cells. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12:641–644. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012060-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Smith J.T., Pounder R.E., Nwokolo C.U. Inappropriate hypergastrinaemia in asymptomatic healthy subjects infected with Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 1990;31:522–525. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.5.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Waldum H.L., Sagatun L., Mjones P. Gastrin and gastric cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2017;8:1. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Asahara M., Kinoshita Y., Nakata H. Gastrin receptor genes are expressed in gastric parietal and enterochromaffin-like cells of Mastomys natalensis. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:2149–2156. doi: 10.1007/BF02090363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kinoshita Y., Ishihara S. Mechanism of gastric mucosal proliferation induced by gastrin. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15(Suppl):D7–D11. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Watanabe T., Yonekura H., Terazono K. Complete nucleotide sequence of human reg gene and its expression in normal and tumoral tissues. The reg protein, pancreatic stone protein, and pancreatic thread protein are one and the same product of the gene. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:7432–7439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bordi C., Falchetti A., Buffa R. Production of basic fibroblast growth factor by gastric carcinoid tumors and their putative cells of origin. Hum Pathol. 1994;25:175–180. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(94)90275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Waldum H.L., Brenna E., Sandvik A.K. Trophic effect of histamine on the stomach. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1991;180:137–142. doi: 10.3109/00365529109093191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fossmark R., Sagatun L., Nordrum I.S. Hypergastrinemia is associated with adenocarcinomas in the gastric corpus and shorter patient survival. APMIS. 2015;123:509–514. doi: 10.1111/apm.12380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xu W., Chen G.S., Shao Y. Gastrin acting on the cholecystokinin2 receptor induces cyclooxygenase-2 expression through JAK2/STAT3/PI3K/Akt pathway in human gastric cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2013;332:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Grabowska A.M., Morris T.M., McKenzie A.J. Pre-clinical evaluation of a new orally-active CCK-2R antagonist, Z-360, in gastrointestinal cancer models. Regul Pept. 2008;146:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Berna M.J., Jensen R.T. Role of CCK/gastrin receptors in gastrointestinal/metabolic diseases and results of human studies using gastrin/CCK receptor agonists/antagonists in these diseases. Curr Top Med Chem. 2007;7:1211–1231. doi: 10.2174/156802607780960519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Rai R., Chandra V., Tewari M. Cholecystokinin and gastrin receptors targeting in gastrointestinal cancer. Surg Oncol. 2012;21:281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chau I., Cunningham D., Russell C. Gastrazole (JB95008), a novel CCK2/gastrin receptor antagonist, in the treatment of advanced pancreatic cancer: results from two randomised controlled trials. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1107–1115. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Boyce M., Moore A.R., Sagatun L. Netazepide, a gastrin/cholecystokinin-2 receptor antagonist, can eradicate gastric neuroendocrine tumours in patients with autoimmune chronic atrophic gastritis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83:466–475. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Singh P., Walker J.P., Townsend C.M., Jr. Role of gastrin and gastrin receptors on the growth of a transplantable mouse colon carcinoma (MC-26) in BALB/c mice. Cancer Res. 1986;46:1612–1616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Smith J.P., Solomon T.E. Effects of gastrin, proglumide, and somatostatin on growth of human colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:1541–1548. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(88)80075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Smith J.P., Stock E.A., Wotring M.G. Characterization of the CCK-B/gastrin-like receptor in human colon cancer. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:R797–R805. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1996.271.3.R797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Upp J.R., Jr., Singh P., Townsend C.M., Jr. Clinical significance of gastrin receptors in human colon cancers. Cancer Res. 1989;49:488–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rehfeld J.F., Bardram L., Hilsted L. Gastrin in human bronchogenic carcinomas: constant expression but variable processing of progastrin. Cancer Res. 1989;49:2840–2843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Smith J.P., Kramer S.T., Solomon T.E. CCK stimulates growth of six human pancreatic cancer cell lines in serum-free medium. Regul Pept. 1991;32:341–349. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(91)90027-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Smith J.P., Solomon T.E., Bagheri S. Cholecystokinin stimulates growth of human pancreatic adenocarcinoma SW-1990. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:1377–1384. doi: 10.1007/BF01536744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Smith J.P., Fantaskey A.P., Liu G. Identification of gastrin as a growth peptide in human pancreatic cancer. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:R135–R141. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.268.1.R135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Watson S.A., Michaeli D., Grimes S. Anti-gastrin antibodies raised by gastrimmune inhibit growth of the human colorectal tumour AP5. Int J Cancer. 1995;61:233–240. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910610216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Watson S.A., Michaeli D., Grimes S. Gastrimmune raises antibodies that neutralize amidated and glycine-extended gastrin-17 and inhibit the growth of colon cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56:880–885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Watson S.A., Michaeli D., Grimes S. A comparison of an anti-gastrin antibody and cytotoxic drugs in the therapy of human gastric ascites in SCID mice. Int J Cancer. 1999;81:248–254. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990412)81:2<248::aid-ijc14>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Watson S.A., Morris T.M., Varro A. A comparison of the therapeutic effectiveness of gastrin neutralisation in two human gastric cancer models: relation to endocrine and autocrine/paracrine gastrin mediated growth. Gut. 1999;45:812–817. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.6.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ajani J.A., Hecht J.R., Ho L. An open-label, multinational, multicenter study of G17DT vaccination combined with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil in patients with untreated, advanced gastric or gastroesophageal cancer: the GC4 study. Cancer. 2006;106:1908–1916. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gilliam A.D., Watson S.A., Henwood M. A phase II study of G17DT in gastric carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:536–543. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]