Abstract

Background:

Prolonged screen time is frequent in children and adolescents. Implementing interventions to reduce physical inactivity needs to assess related determinants. This study aims to assess factors associated with screen time in a national sample of children and adolescents.

Methods:

This nationwide study was conducted among 14,880 students aged 6–18 years. Data collection was performed using questionnaires and physical examination. The World Health Organization-Global School Health Survey questionnaire was used. Logistic regression analysis was used to examine the relationship between demographic variables, socioeconomic status (SES), family structure, physical activity, unhealthy eating habits, body mass index, and mental distress with screen time.

Results:

The participation rate was 90.6% (n = 13,486), 50.8% were male, and 75.6% lived in urban areas. Mean (standard deviation) age of participants was 12.47 (3.36) years. The SES, eating junk foods, urban residence, and age had significant association with screen time, watching television (TV), and computer use (P < 0.05). With increasing number of children, the odds ratio of watching TV reduced (P < 0.001). Statistically, significant association existed between obesity and increased time spent watching TV (P < 0.001). Girls spent less likely to use computer and to have prolonged screen time (P < 0.001). Participants in the sense of worthlessness were less likely to watch TV (P = 0.005). Screen time, watching TV, and using computer were higher in students with aggressive behaviors (P < 0.001); screen time was higher in those with insomnia.

Conclusions:

In this study, higher SES, unhealthy food habits, and living in urban areas, as well as aggressive behaviors and insomnia increased the risk of physical inactivity.

Keywords: Children and adolescents, determinants, screen time

Introduction

Sedentary behaviors include activities while sitting or reclining with the least energy expenditure.[1] Screen time, which is often used for assessing sedentary behaviors, is defined as the time adolescents spend on watching television (TV), video games, and using a computer.[2]

Recommendations for watching TV in children is up to 2 h/day.[3] However, most children and adolescents do not adhere to these guidelines as screen time in 79.5% of adolescents in Brazil is more than 2 h/day.[4]

A cross-sectional study in Barcelona also revealed that about 50% of students spend more than 2 h/day on watching TV. A total of 68.2% of boys and 61.7% of girls use computer more than 2 h/week.[5] In this context, a cross-sectional study on 370 children in Korea showed that screen time in about 46% of children is 1–2.9 h and in 8.9% is more than 3 h/day.[6] A national study reported that approximately 33.4% and 53% of Iranian students aged 6–18 years spend their time for watching TV or video on weekdays and on weekend, respectively, and about half of urban students and a quarter of rural students used a personal computer (PC).[7]

Unfavorable lifestyle habits of children and adolescents, especially sedentary behaviors, threat to health in this group, and the population is at risk for cardiovascular epidemics such as cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, and psychological disorders.[8] In this context, evidence suggests that increased time watching TV was associated with an increase in obesity in children and adolescents.[9,10,11,12] A number of studies reported the association between screen time and increased risk of metabolic syndrome or its components in children and adolescents.[13,14,15,16,17,18] Evidence suggests that sedentary behaviors formed in childhood and continues into adolescence and adulthood.[19,20,21,22]

Research has been done on factors related to screen time, and meta-analysis study showed that children with overweight and obesity had more risk for screen time more than 2 h compared to children with normal weight.[23] Data showed that high socioeconomic status (SES),[4] unhealthy eating habits,[5] depression, and mental problems[24] are related to screen time.

Most studies have studied the effect of factors related to screen time,[4,5,6] while a few studies assessed separately the factors associated with time spent watching TV or using a computer. On the other hand, there is evidence about factors affecting screen time often in developed countries and in developing countries; especially, our country has limited studies. This study aims to assess the factors associated with screen time in Iranian children and adolescents.

Methods

This study was performed as part of the fourth survey of the national schoolbased surveillance system entitled the “Childhood and Adolescence Surveillance and Prevention of Adult Noncommunicable Disease” study. The methods of CASPIAN-IV study were described previously.[25] The participants of the present study were selected from elementary, intermediate, and high school by a cluster sampling method in 30 provinces of Iran (48 clusters of 10 people in each province). Totally, 13,486 students in the age range of 6–18 years were participants in this study. The students who did not have data about time spent watching TV and using computer were excluded from the study.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical Committees, and participants signed informed consent after receiving explanation of the study protocols.

Measurements

Data were obtained by the questionnaire of the World Health Organization-Global Student Health Survey that validity and reliability were assessed previously.[26]

SES was assessed through principal component analysis methods by some variables including parents’ education, parents’ occupation, possessing private car, school type (public/private), type of home (rented/private), and having PC in the home, which were summarized in one main component. This main component was classified into tertiles. The first tertile was defined as low, second tertile as moderate, and third tertile as high SES.

Physical activity was estimated by two questions. (1) During the past week, on how many days were you physically active for overall 30 min per day? Responses options were from 0 to 7 days. (2) How much time do you spend in exercise class regularly in school per week? Responses ranged from 0 to 3 or more hours. Physical activity was categorized into tertiles. The first tertile was defined as a mild, second tertile as a moderate, and third tertile as a severe.

Psychiatric distress included worry, depression, confusion, insomnia, anxiety, and aggression, and feelings of being worthless were assessed by seven questions.

The screen time behavior of children was assessed by a questionnaire that asked the child to report the average number of hours per day spent watching TV/VCDs, PC, and electronic games. Screen time activity was categorized into two groups (<2 h/day and ≥2 h).

To assess dietary habits, food frequency questionnaire was applied and nine items include sweets, salty/fatty snacks, soda, fruits, dried fruit, vegetables, sugar-sweetened drinks, milk, and fast food. Five groups of foods were considered as unhealthy foods, including sweets, salty/fatty snacks, soda, sugar-sweetened drinks, and fast food. Unhealthy food was categorized into tertiles. The first tertile was defined as a mild, second tertile as a moderate, and third tertile as a severe.

Anthropometric measurements

Anthropometric indexes were measured according to the standard protocol. Height was recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm without shoes, and weight with minimal clothing with 0.1 kg accuracy using calibrated instruments. BMI was calculated as weight divided by height (in kg/m2).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed by the STATA software version 10.0 (STATA Corp, College Station, Texas, USA). The categorical variables were presented as number (%) and continuous variables were summarized as mean (standard deviation [SD]). Comparisons of means were investigated by t-test. The Pearson's Chi-square test was used to analyze categorical variables. Logistic regression was performed to assess the association of independent variables with screen time in different models for adjusting potential confounders. Method of sampling (cluster sampling) was considered in all statistical analyses. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

The participation rate was 90.6% (n = 13, 486); 50.8% were boys, and 75.6% lived in urban regions. The mean (SD) age of participants was 12.47 (3.36) years. In total, 50.66% of students watched TV more than 2 h/day, 9.63% of those used a computer more than 2 h/day in their leisure time, and 18.62% of students had screen time more than 4 h/day.

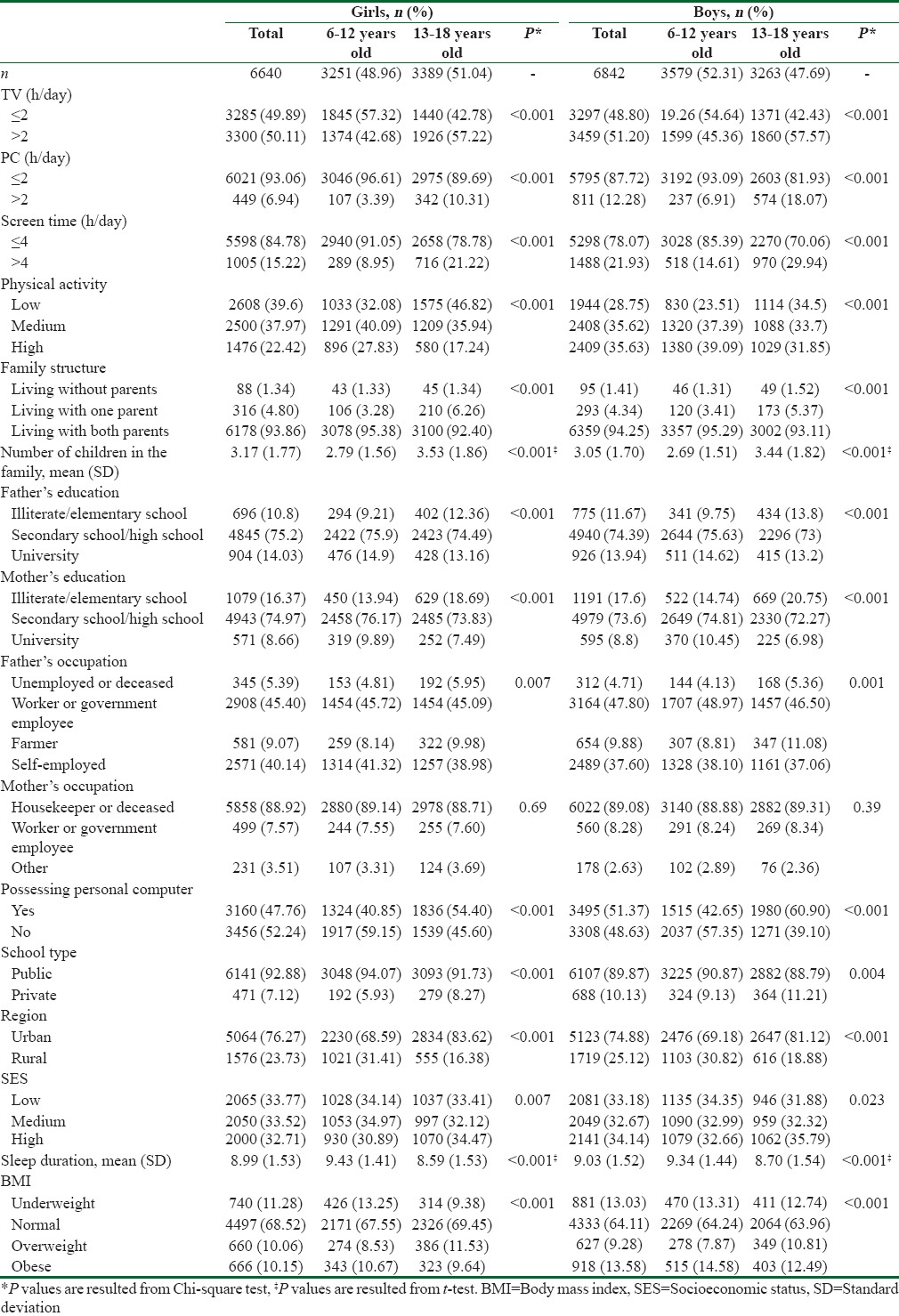

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of students according to sex and age. In both sex groups, the frequency of watching TV (more than 2 h), using computer (more than 2 h), and screen time (more than 4 h) was significantly higher in the age group of 13–18 years than age group of 6–12 years. In addition, the age group of 13–18 years had more PC and higher SES than age group 6–12 years (P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population according to sex and age: The CASPIAN-IV study

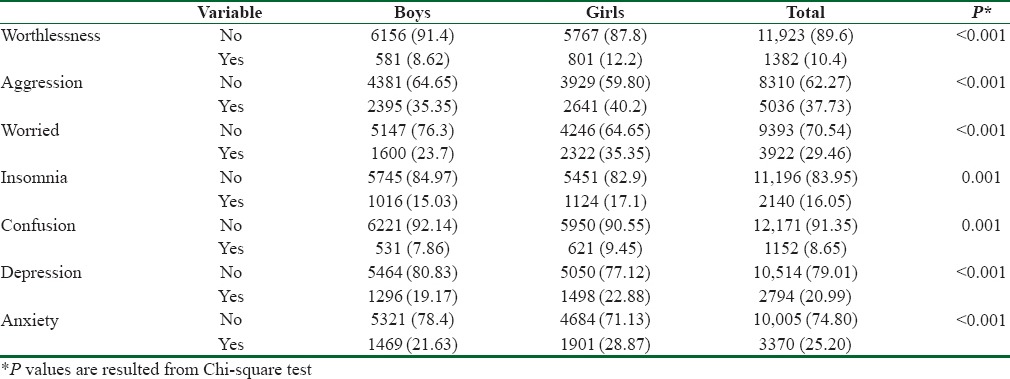

Prevalence of psychiatric distress by sex is shown in Table 2. The results presented that significantly, the prevalence of psychiatric distress was higher in girls than boys (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Prevalence of psychiatric distress by gender: The CASPIAN-IV study

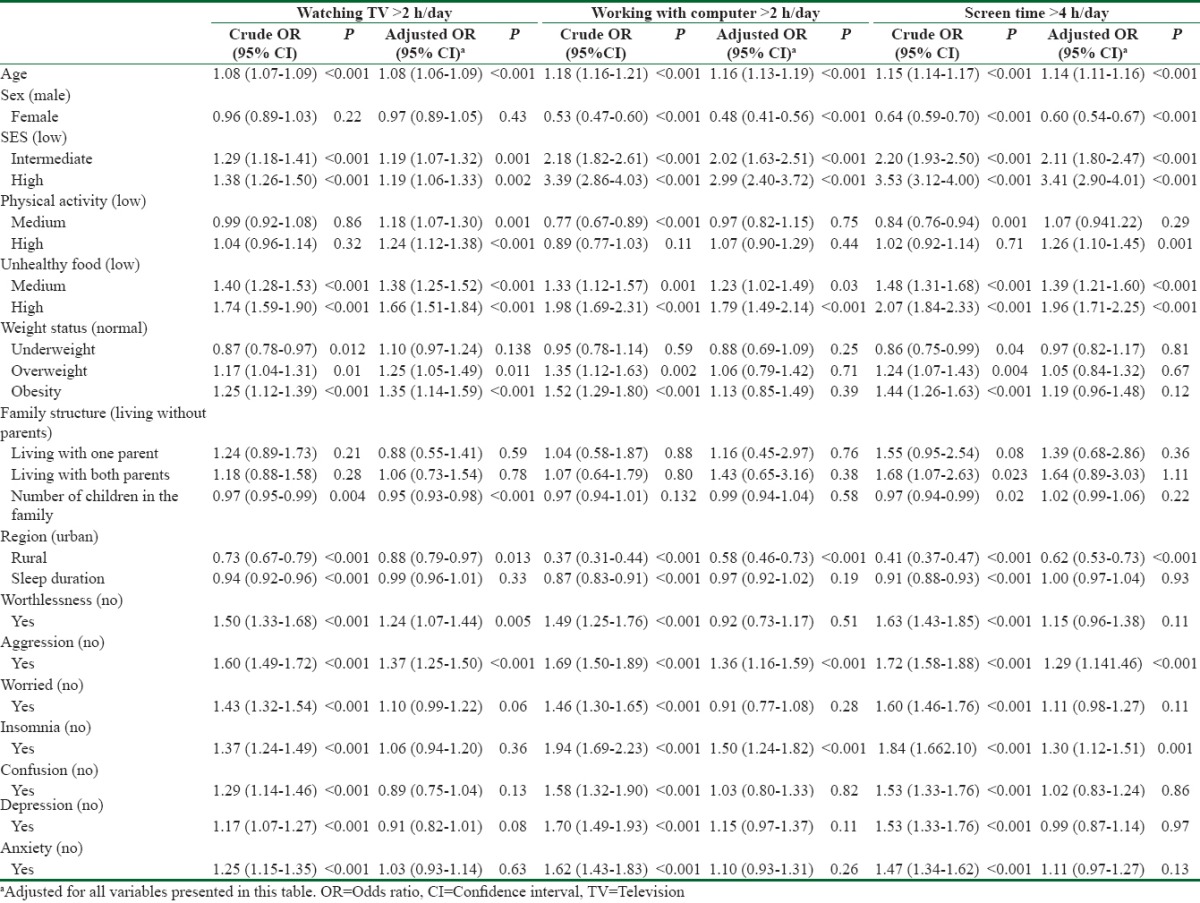

Table 3 presents the association of independent variables with screen time in logistic model. The results showed that older participants had significantly higher risk for higher watching TV, using computer, and screen time (P < 0.001). Significantly, girls had less risk for using computer and screen time than boys (P < 0.001). Students from high SES regions and students with unhealthy diet had greater risk for higher watching TV, using computer, and screen time (P < 0.001). Overweight and obese students significantly had more risk for high watching TV. With the increasing number of children, the risk of watching TV significantly decreased (P < 0.001). Participants with insomnia and aggression significantly had higher risk for higher using computer and screen time (P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Association of independent variables with screen time in logistic regression model: The CASPIAN-IV study

Discussion

The findings of the present study showed that students with higher SES, unhealthy food habits, from urban areas, and older had higher risk for higher watching TV, using computer, and screen time. The findings of previous studies showed that there was a significant association between age increasing with screen time,[20,27,28,29,30,31] which was consistent with our results. The results of Babey et al.'s study indicated that age was positive associated with using computer, while no significant association was found between age and time spent watching TV.[32]

In the present study, no significant association was seen between sex and time spent watching TV, which was consistent with previous studies.[33,34] Data showed that boys had more risk for high screen time than girls,[4,6,23,28,29] which was consistent with our results. The high level of screen time in boys may due to high using computer and video games,[35] and on the other hand, in girls in addition to watching TV, other sedentary behaviors such as talking on the phone, listening to music,[36] and reading[37] were seen more than boys.

The results of our study presented that students from urban regions had higher risk for watching TV, using computer, and screen time. A cross-sectional study in Greece showed that living in urban is associated with high risk of watching TV.[38] In urban regions, high access to cafenets, internet, computer games, and, on the other hand, increasing urbanization and decreasing access to safe environment for playing cause watching TV and using computer, which are the main entertainments of children and adolescents.

In the current study, participants from high SES regions had higher risk watching TV, using computer, and screen time. Our results were consistent with other studies.[4,29,39] High level of screen time in high SES level may due to great access to electronic devices, video games, and computer. The results of a study in Columbia showed that factors such as working mother and income families were positively associated with access to electronic devices, TV, and computer in a child room.[40]

Significant association between physical activity and time spent watching TV and screen time was found in our study. The results of studies have been inconsistent, but some data showed that watching TV and using computer may replace physical activity in children and adolescents.[41] Previous study indicated that low level of physical activity was related to increased time spent watching TV and using computer.[32]

In the present study, no significant association was found between family structure and time spent watching TV, using computer, and screen time. The results of our study were consistent with previous study.[30] In our study, with increasing number of family's children, the risk of watching TV decreased. The results of a cross-sectional study in Barcelona showed that boys who live with both parents use media less than boys who live with one parent.[5]

Data presented no significant association between weight and screen time,[4,5] which was consistent with our results. While other studies showed that obesity was positively associate with increase of screen time,[6,23,39] in our study students with overweight and obesity significantly had higher risk of increasing time spent watching TV. In addition, in our study, positive association was found between unhealthy eating habits and screen time. Results of other studies showed that unhealthy eating habits were associated significantly with screen time.[5,6,42] The findings of study in Belgium showed that unhealthy eating habits such as high consumption of soda and chips in early adolescence predict the high screen time in early adulthood.[42] Data indicated that fast food consumption and eating junk food were associated with screen time and increasing time spent watching TV.[6,42]

In our study, students who had experience of worthlessness had high risk for increasing watching TV, and aggressive students had more risk for increased time spent watching TV, using computer, and screen time. Furthermore, students with insomnia had high risk for using computer and screen time. Data showed that depression was in related to time spent watching TV and video games.[24,43] In the present study, there was no significant association found between depression and watching TV that may due to different data collection method.

Our study had some limitations. The study design was cross-sectional that not allowed to conclusion about causation. Despite these limitations, main strength of the current study was large sample.

Conclusions

Findings show the association of age, SES, living area, eating junk foods, and some psychiatric distress with screen time, watching TV, and using computer during leisure time. Effective interventions should consider the modifiable risk factors to reduce the screen time and its adverse health effects.

Financial support and sponsorship

The main study was conducted as a national school-based surveillance program. The current study was funded by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Project code: 294176).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Pate RR, O’Neill JR, Lobelo F. The evolving definition of “sedentary”. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2008;36:173–8. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3181877d1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Owen N, Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW. Too much sitting: The population health science of sedentary behavior. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2010;38:105–13. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e3181e373a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Public Education. American Academy of Pediatrics: Children, adolescents, and television. Pediatrics. 2001;107:423–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Lucena JM, Cheng LA, Cavalcante TL, da Silva VA, de Farias Júnior JC. Prevalence of excessive screen time and associated factors in adolescents. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2015;33:407–14. doi: 10.1016/j.rpped.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garcia-Continente X, Pérez-Giménez A, Espelt A, Nebot Adell M. Factors associated with media use among adolescents: A multilevel approach. Eur J Public Health. 2014;24:5–10. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckt013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ham OK, Sung KM, Kim HK. Factors associated with screen time among school-age children in Korea. J Sch Nurs. 2013;29:425–34. doi: 10.1177/1059840513486483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jari M, Qorbani M, Motlagh ME, Heshmat R, Ardalan G, Kelishadi R. A Nationwide Survey on the daily screen time of Iranian children and adolescents: The CASPIAN-IV study. Int J Prev Med. 2014;5:224–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katzmarzyk PT, Ardern C. Physical activity levels of Canadian children and youth: Current issues and recommendations. Can J Diabetes. 2004;28:67–78. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tremblay MS, LeBlanc AG, Kho ME, Saunders TJ, Larouche R, Colley RC, et al. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:98. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prentice-Dunn H, Prentice-Dunn S. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and childhood obesity: A review of cross-sectional studies. Psychol Health Med. 2012;17:255–73. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2011.608806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Väistö J, Eloranta AM, Viitasalo A, Tompuri T, Lintu N, Karjalainen P, et al. Physical activity and sedentary behaviour in relation to cardiometabolic risk in children: Cross-sectional findings from the Physical Activity and Nutrition in Children (PANIC) study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:55. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Byun W, Dowda M, Pate RR. Associations between screen-based sedentary behavior and cardiovascular disease risk factors in Korean youth. J Korean Med Sci. 2012;27:388–94. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2012.27.4.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mark AE, Janssen I. Relationship between screen time and metabolic syndrome in adolescents. J Public Health (Oxf) 2008;30:153–60. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdn022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang HT, Lee HR, Shim JY, Shin YH, Park BJ, Lee YJ. Association between screen time and metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents in Korea: The 2005 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;89:72–8. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grøntved A, Ried-Larsen M, Møller NC, Kristensen PL, Wedderkopp N, Froberg K, et al. Youth screen-time behaviour is associated with cardiovascular risk in young adulthood: The European Youth Heart Study. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:49–56. doi: 10.1177/2047487312454760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez-Gomez D, Tucker J, Heelan KA, Welk GJ, Eisenmann JC. Associations between sedentary behavior and blood pressure in young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:724–30. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardy LL, Denney-Wilson E, Thrift AP, Okely AD, Baur LA. Screen time and metabolic risk factors among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:643–9. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danielsen YS, Júlíusson PB, Nordhus IH, Kleiven M, Meltzer HM, Olsson SJ, et al. The relationship between life-style and cardio-metabolic risk indicators in children: The importance of screen time. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100:253–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.02098.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biddle SJ, Pearson N, Ross GM, Braithwaite R. Tracking of sedentary behaviours of young people: A systematic review. Prev Med. 2010;51:345–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stierlin AS, De Lepeleere S, Cardon G, Dargent-Molina P, Hoffmann B, Murphy MH, et al. A systematic review of determinants of sedentary behaviour in youth: A DEDIPAC-study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:133. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0291-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janz KF, Burns TL, Levy SM Iowa Bone Development Study. Tracking of activity and sedentary behaviors in childhood: The iowa bone development study. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:171–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birch LL, Fisher JO. Development of eating behaviors among children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1998;101(3 Pt 2):539–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atkin AJ, Sharp SJ, Corder K, van Sluijs EM International Children's Accelerometry Database (ICAD) Collaborators. Prevalence and correlates of screen time in youth: An international perspective. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:803–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hume C, Timperio A, Veitch J, Salmon J, Crawford D, Ball K. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and depressive symptoms among adolescents. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8:152–6. doi: 10.1123/jpah.8.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kelishadi R, Ardalan G, Qorbani M, Ataie-Jafari A, Bahreynian M, Taslimi M, et al. Methodology and early findings of the fourth survey of childhood and adolescence surveillance and prevention of adult non-communicable disease in Iran: The CASPIAN-IV study. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:1451–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelishadi R, Majdzadeh R, Motlagh ME, Heshmat R, Aminaee T, Ardalan G, et al. Development and evaluation of a questionnaire for assessment of determinants of weight disorders among children and adolescents: The CASPIAN-IV study. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:699–705. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nelson MC, Neumark-Stzainer D, Hannan PJ, Sirard JR, Story M. Longitudinal and secular trends in physical activity and sedentary behavior during adolescence. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1627–34. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoyos Cillero I, Jago R. Sociodemographic and home environment predictors of screen viewing among Spanish school children. J Public Health (Oxf) 2011;33:392–402. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdq087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trang NH, Hong TK, van der Ploeg HP, Hardy LL, Kelly PJ, Dibley MJ. Longitudinal sedentary behavior changes in adolescents in Ho Chi Minh City. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:223–30. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carson V, Janssen I. Associations between factors within the home setting and screen time among children aged 0-5 years: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:539. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoyos Cillero I, Jago R. Systematic review of correlates of screen-viewing among young children. Prev Med. 2010;51:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Babey SH, Hastert TA, Wolstein J. Adolescent sedentary behaviors: Correlates differ for television viewing and computer use. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hinkley T, Salmon J, Okely AD, Trost SG. Correlates of sedentary behaviours in preschool children: A review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:66. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorely T, Marshall SJ, Biddle SJ. Couch kids: Correlates of television viewing among youth. Int J Behav Med. 2004;11:152–63. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1103_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olds TS, Maher CA, Ridley K, Kittel DM. Descriptive epidemiology of screen and non-screen sedentary time in adolescents: A cross sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:92. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bauer KW, Friend S, Graham DJ, Neumark-Sztainer D. Beyond screen time: Assessing recreational sedentary behavior among adolescent girls. J Obes 2012. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/183194. 183194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rey-López JP, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Ortega FB, Ruiz JR, Martinez-Gómez D, De Henauw S, et al. Sedentary patterns and media availability in European adolescents: The HELENA study. Prev Med. 2010;51:50–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kourlaba G, Kondaki K, Liarigkovinos T, Manios Y. Factors associated with television viewing time in toddlers and preschoolers in Greece: The GENESIS study. J Public Health (Oxf) 2009;31:222–30. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.LeBlanc AG, Broyles ST, Chaput JP, Leduc G, Boyer C, Borghese MM, et al. Correlates of objectively measured sedentary time and self-reported screen time in Canadian children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:38. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0197-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Camargo DM, Orozco LC. Associated factors to availability and use of electronic media in children from preschool to 4th grade. Biomedica. 2013;33:175–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tammelin T, Ekelund U, Remes J, Näyhä S. Physical activity and sedentary behaviors among Finnish youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1067–74. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b13e318058a603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Busschaert C, Cardon G, Van Cauwenberg J, Maes L, Van Damme J, Hublet A, et al. Tracking and predictors of screen time from early adolescence to early adulthood: A 10-year follow-up study. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:440–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmitz KH, Lytle LA, Phillips GA, Murray DM, Birnbaum AS, Kubik MY. Psychosocial correlates of physical activity and sedentary leisure habits in young adolescents: The teens eating for energy and nutrition at school study. Prev Med. 2002;34:266–78. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]