Abstract

Penile inflammatory skin conditions such as balanitis and posthitis are common, especially in uncircumcised males, and feature prominently in medical consultations. We conducted a systematic review of the medical literature on PubMed, EMBASE, and Cohrane databases using keywords “balanitis,” “posthitis,” “balanoposthitis,” “lichen sclerosus,” “penile inflammation,” and “inflammation penis,” along with “circumcision,” “circumcised,” and “uncircumcised.” Balanitis is the most common inflammatory disease of the penis. The accumulation of yeasts and other microorganisms under the foreskin contributes to inflammation of the surrounding penile tissue. The clinical presentation of inflammatory penile conditions includes itching, tenderness, and pain. Penile inflammation is responsible for significant morbidity, including acquired phimosis, balanoposthitis, and lichen sclerosus. Medical treatment can be challenging and a cost burden to the health system. Reducing prevalence is therefore important. While topical antifungal creams can be used, usually accompanied by advice on hygiene, the definitive treatment is circumcision. Data from meta-analyses showed that circumcised males have a 68% lower prevalence of balanitis than uncircumcised males and that balanitis is accompanied by a 3.8-fold increase in risk of penile cancer. Because of the high prevalence and morbidity of penile inflammation, especially in immunocompromised and diabetic patients, circumcision should be more widely adopted globally and is best performed early in infancy.

Keywords: Balanitis, circumcision male, foreskin, infection, inflammation, lichen sclerosus

Introduction

Inflammatory lesions of the glans penis (balanitis), of the foreskin (posthitis), or both (balanoposthitis) are common.[1,2] They are painful and can be associated with penile bleeding, lichen sclerosus (LS), and complications such as phimosis and paraphimosis. Fungal infections are usually responsible, most commonly involving the yeast, Candida albicans, potentially associated with polymicrobial flora.[3] Genital yeast infection (termed “candidiasis” or “thrush”) is uncommon in healthy individuals, but in immunocompromised individuals, such as those with HIV infection, in diabetic and cancer patients C. albicans can also cause bloodstream infection with serious consequences.[4] Globally, the annual incidence of C. albicans infection is approximately 400,000, most cases occurring in economically developed regions.[4] The attributable (27%) mortality rates are very high.[4] Infected individuals are less able to mount a cytokine response to limit the damage caused by the C. albicans peptide toxin candidalysin, responsible for the epithelial damage caused when hyphae (filamentous structures of yeast) breach the epidermal barrier of the host cell.[5] A strong direct link of C. albicans antibodies with schizophrenia in men, independent of potential confounders, has been reported.[6]

Penile inflammatory conditions can occur at any age, being more common in males with primary phimosis, and can also cause secondary phimosis. Recent evidence-based policy statements recognize that circumcision can protect against penile inflammation.[7,8,9,10]

The present review discusses the various penile inflammatory skin conditions and the protective role of circumcision.

Methods

The PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane databases were searched on May 15, 2016, for “balanitis,” “posthitis,” “balanoposthitis,” “lichen sclerosus,” “penile inflammation,” and “inflammation penis.” We then searched for publications matching one or more of the keywords “circumcision,” “circumcised,” or “uncircumcised” plus one or more of the keywords above. EMBASE and Cochrane database searches did not identify additional articles. The title and abstract of each article retrieved was used to judge whether it was of sufficient quality to merit detailed review. Inclusion criteria included either nonduplicated original data or a meta-analysis of original data, and peer-reviewed journal publication. Reference lists were searched for additional articles. Major reviews were used for presenting clinical background.

Results and Discussion

Articles included

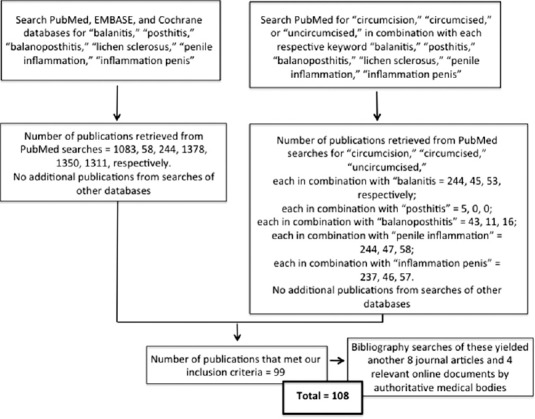

Figure 1 shows the results of the search strategy we used.

Figure 1.

Search strategy and results

Balanitis

Clinical presentation and causes

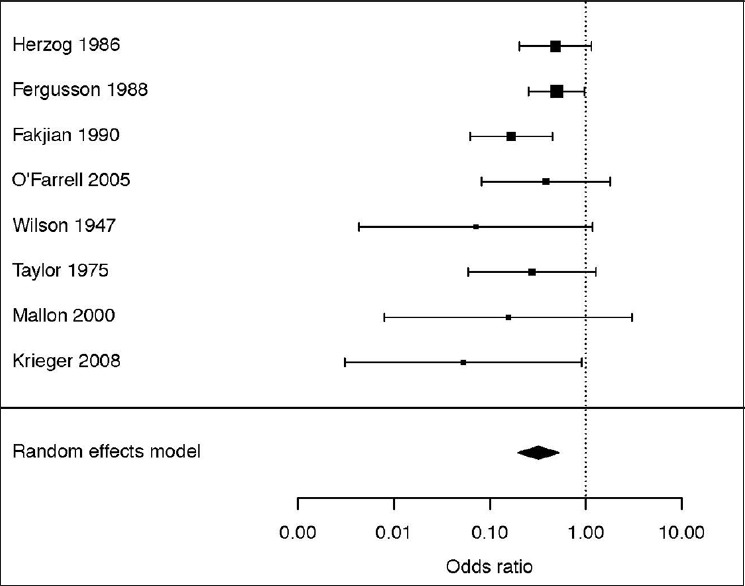

Balanitis presents with mild burning, pruritis, itching, swelling, erythematous patches, and plaques or bullae involving the glans penis, satellite eroded pustules and moist curd-like accumulations[1] [Figure 2]. In uncircumcised men, the foreskin is often involved (balanoposthitis).[1] Balanitis has worse clinical presentation in diabetic and immunocompromised patients, with fulminating edema or ulcers in severe cases.[1]

Figure 2.

Clinical presentation of balanitis. Reprinted from English et al.[1]

Poor hygiene is the most common cause. Irritant balanitis can result from exposure to medications, such as some common antibiotics, and to allergens, including latex condoms, propylene glycol in lubricants, some spermicides, and corticosteroids. Ammonia, released from urine by bacterial hydrolysis of urea, can induce inflammation of the glans and foreskin. Another common irritant responsible for contact dermatitis is frequent washing with soaps containing topical allergens or irritants.

Microbiology of balanitis

Various bacterial species and yeasts under the foreskin have the potential to cause penile inflammatory conditions. C. albicans is the most frequent fungal isolate from the penis.[11] Fungi are normal flora, but overgrowth can occur in certain conditions, especially in diabetic patients with phimosis. Candida colonization was seen in 16% of men visiting a sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinic in Coventry, the UK.[12] Symptomatic infection due to C. albicans is more common in uncircumcised males.[3] Bacterial superinfection with Streptococci or Staphylococci increases pain.

Bacteria, especially Streptococcus spp., by themselves are the second most common cause of infectious balanitis. Less common are Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Klebsiella spp., Staphylococcus epidermidis, Enterococcus, Proteus spp., Morganella spp., and Escherichia coli.[1]

Chlamydia trachomatis, genital mycoplasmas, and bacterial STIs such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Haemophiluis ducreyi, and others can be associated with balanitis and balanoposthitis.[1] N. gonorrhoeae produces an endotoxin likely responsible for edema and erythrema of the foreskin.[13] Gardnerella vaginalis is responsible for symptomatic anaerobic-related balanitis in men; presentation includes a subpreputial “fishy”-smelling discharge similar to the odor from bacterial vaginosis in women.[1] The prevalence of G. vaginalis was 15% and 25% among heterosexual attendees at STI clinics in London[14] and Alabama,[15] respectively. Other causes of balanitis and balanoposthitis include viral STIs, such as high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types, and parasitic infections such as Trichomonas vaginalis and protozoa, all more common in uncircumcised men.[1]

Balanitis in boys

Approximately 4% of boys get balanitis, most commonly during the preschool years.[16] Balanitis is especially common in uncircumcised boys aged under 5 years with phimosis (25%) compared with those without phimosis (6%).[17] For males over 5 years of age, these figures are 24% versus 12%, respectively.[17] Ballooning was also more common in uncircumcised boys suffering from phimosis (34% vs. 2% and 20% vs. 4% for the respective age groups).[17] Overgrowth of yeasts as well as other microorganisms that favor development of balanitis can follow antibiotic treatment. Any factor that increases microorganisms substantially has the potential to contribute to balanitis in boys.

A major predisposing factor in boys is lack of circumcision, especially in those whose foreskin is partly or completely nonretractable.[16] An obvious medical reason for circumcision of boys is protection against balanitis and posthitis.[3] The incidence of balanitis in boys is over 2-fold higher in the uncircumcised.[18,19,20,21] Cases of balanitis caused by group A or B hemolytic Streptococcus spp. have been reported in prepubertal[22] and postpubertal[23] uncircumcised boys, respectively. Newer pyrosequencing methods (see subsection below) are needed to confirm and expand on findings in boys.

A study in India of 124 boys aged 6 weeks to 8 years swabbed before circumcision found that E. coli, Proteus spp., and Klebsiella spp., were the most common bacteria.[24] After circumcision, bacterial cultures were negative in 66%. Swabs of smegma from 52 uncircumcised Nigerian boys aged 1 week to 11 years identified 50 bacterial isolates, 58% being Gram-positive, and 42% Gram-negative; E. coli was the most common Gram-negative bacterium.[25] A Turkish study of 100 prepubertal boys swabbed before circumcision identified 72 organisms, 75% being Gram-positive bacteria, 24% Gram-negative bacteria, and 1% Candida spp.[26] Nine percent of boys had high-risk HPV genotypes. Most bacteria were multidrug resistant and included species capable of causing urinary tract infections. Another Turkish study, involving 78 boys aged 1 month to 14 years (mean 3.9 years), found bacterial growth in 72% before circumcision, but in only 10% after circumcision.[27] Bacterial growth was seen in all boys with phimosis; growth decreased progressively to approximately 50% for greater exposure of the glans. The most common organisms were Enterococcus (33%), Staphylococcus spp. (15%), E. coli (13%), Proteus spp. (7%), and Klebsiella spp. (3%).

C. albicans, but no other fungi, was found in 3.5% of 200 Iranian infants before circumcision.[28] In boys aged 8 months to 18 years (mean 6.4 years), fungus incidence was 44% in uncircumcised boys, compared to 18% in circumcised boys.[29] The fungal species were as follows: Malassezia globosa, Malassezia furfur, Malassezia slooffiae, C. albicans, Candida tropicalis, and Candida parapsilosis. All were present in uncircumcised infants, but none in circumcised infants. A gradual accumulation with age occurred to 37.5% by the age of 18 years in circumcised boys compared to the prevalence of 62.5% in uncircumcised boys.

Balanitis in adult males

Lack of circumcision has been consistently associated with balanitis in men.[30] Other causes include exposure to certain medications, allergens, and chemical irritants. Balanitis was reported in 11%–13% of uncircumcised men, but in only 2% of circumcised men.[20,21] A 3-year prospective review of men aged 16–95 years (mean age 47 years) at a multi-specialty penile dermatology clinic in Edinburgh, UK, diagnosed nonspecific balanitis in 22% of patients.[31] When circumcision status was documented, 53% were uncircumcised and 18% were circumcised. An STI clinic in Portugal found that the prevalence of balanitis in men (all uncircumcised) was 11%.[32] A large randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving young men found balanitis in 0.7% of the uncircumcised men over the 18 months of follow-up, but in none of the men who received circumcision.[33]

Diabetic uncircumcised men have a high (35%) prevalence of symptomatic balanitis.[20,21] Among men with acquired phimosis, 26% had a history of diabetes.[34] Phimosis increases the risk of infection of the foreskin and glans. During the period of 1942–1945 in World War II, there were 146,000 hospitalizations of US troops for balanitis, balanoposthitis, phimosis, and paraphimosis.[35] It was remarked that “the man-hours lost as a result of circumcisions and adjuvant therapy were expensive to the war effort and exasperated the commanding officers”.[35] “Time and money could have been saved had prophylactic circumcision been performed before the men were shipped overseas.”[35]

A study of 350 Indian men found that the uncircumcised men were more likely to harbor bacterial pathogens in the coronal sulcus; Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and any pathogen were 1.9, 2.4 and 2.8 times higher, respectively.[36]

Smegma, produced under the foreskin, consists of 27% fat and 13% protein, and contributes to the higher occurrence of Malassezia spp. in uncircumcised versus circumcised men (49% vs. 7%).[37] The frequency of yeast colonization was reduced from 11% to 1.3% (P < 0.008) by circumcision.[38]

The uncircumcised penis is an important niche for genital anaerobes associated with bacterial vaginosis in female partners.[39] Bacterial vaginosis risk to female partners is reduced by male circumcision.[40] The causative anaerobic genera significantly decreased by circumcision include Anaerococcus, Finegoldia, Peptoniphilus, and Prevotella.[41] These bacteria are exchanged between partners during sexual intercourse.[39]

Complete microbiome determined by pyrosequencing

Sophisticated 16S rRNA gene-based quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and pyrosequencing, log response ratio, Bayseyan classification, nonmetric multidimensional scaling, and permutational multivariate analysis have been used in recent years to provide a much more complete picture of the penile microbiome than traditional clinical microbiological approaches.

A study in Rakai, Uganda, using this technology found a greater microbial diversity on coronary sulcus swabs of uncircumcised men before circumcision than 12 months after circumcision.[41] Anaerobic bacterial families decreased from 72 to 4.8 (P < 0.014) and facultative anaerobic families increased from 23 to 79 (P = 0.006), while abundance of aerobic bacteria did not differ significantly before and after circumcision (236 vs. 467). An RCT found significant reduction in prevalence, composition, and load of 12 anaerobic bacterial taxa 1 year after circumcision.[42] The prevalence and absolute abundance of 12 anaerobic bacterial taxa decreased significantly in the men who were circumcised. It was suggested that reduction in anaerobes might account in part for the ability of circumcision to reduce human immunodeficiency virus infection. An increase in the prevalence of two types of aerobic bacteria (Corynebacterium spp. and Staphylococcus spp.), which are skin commensals, was seen after circumcision.

A US study involving qPCR and pyrosequencing detected bacterial vaginosis-associated taxa (including Atopobium, Megasphaera, Mobiluncus, Prevotella, and Gemella) in coronal sulcus specimens of both sexually experienced and inexperienced males aged 14–17 years.[43] Porphyrmonas was higher in uncircumcised men (6.4% vs. 0.3%) and Prevotella spp. were found in abundance only in uncircumcised males. In contrast, Staphylococcus spp. were enriched in circumcised participants (27% vs. 5.5%).[39]

Pyrosequencing data are consistent with conventional clinical microbiology results, so adding to the reliability of conclusions drawn based only on the latter.

Meta-analysis of balanitis and circumcision status

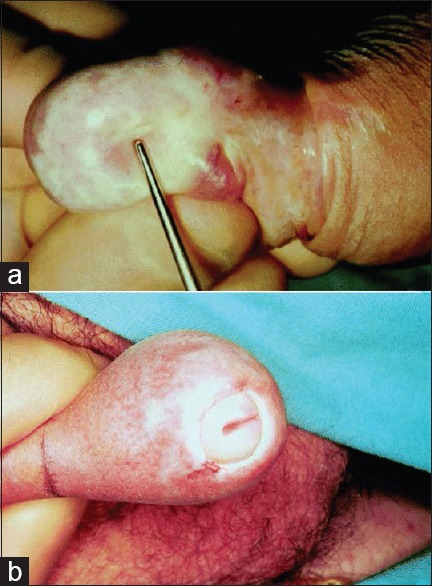

Figure 3 shows a Forest plot from a meta-analysis of 8 relevant studies.[18,19,20,30,33,44,45,46] This found that prevalence of balanitis was 68% lower in circumcised versus uncircumcised males (odds ratio = 0.32; 95% CI 0.20–0.52)[47] i.e., was 3.1 times (95% CI 1.9–5.0) higher in uncircumcised males.

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of association of lack of circumcision with penile inflammation. Reprinted from Morris et al.[47]

Treatment of balanitis

Topical antifungals, if applied consistently until symptoms disappear, may be effective in treatment of sexually acquired balanitis.[48] Recurrence is frequent, however, especially in patients with risk factors such as phimosis or diabetes. Treatment of the partner is important to reduce the risk of relapse. Prevention entails good hygiene and circumcision during childhood.

Balanoposthitis

Overview

This condition only occurs in uncircumcised males. The prevalence is lower than balanitis.[16] The entire distal penis (foreskin and glans) presents as red, painful, and swollen, often accompanied by a foul-smelling, purulent discharge.[49] Balanophosthitis can involve a vicious cycle. After each infection, the foreskin will heal by fibrosis, in which there is thickening and scarring of connective tissue, and this will further shrink the tight foreskin. Balanoposthitis represents a strong medical indication for circumcision.

Balanoposthitis in boys

In childhood, balanoposthitis presents most commonly between ages 2 and 5 years,[16] which contradicts claims of soiled diapers, etc., as a major cause of penile inflammation. In young boys, balanoposthitis is often associated with phimosis and inability to clean under the foreskin because the foreskin is still lightly attached to the underlying penis.[49]

Balanoposthitis in men

This condition was found in 20% of 194 consecutive unselected UK men, all uncircumcised.[50] A Brazilian study of men presenting for prostate cancer screening identified balanoposthitis in 12%.[51] The prevalence was 58% higher in those with a history of nonspecific urethritis.[51] Balanoposthitis is especially common in uncircumcised diabetic men,[20,51,52] a dysfunctional, shrunken penis likely a contributing factor.[20] Not surprisingly, balanoposthitis in diabetic men adds to their frequent diabetic neuropathy and peripheral vascular disease, so contributing to their sexual dysfunction. Diabetes is common, inherited, and rising in incidence. Thus, in the opinion of the authors, family history of diabetes may add to considerations for circumcising a newborn infant.

Treatment of balanoposthitis

Local hygienic measures have been suggested for the treatment of nonspecific balanoposthitis.[53] If the condition is recalcitrant, antifungal and antibiotic creams can be used.[53] Circumcision is the definitive treatment for the prevention of future occurrence.[48,53] A study of 476 boys who were circumcised beyond the neonatal period found that balanoposthitis was the reason for performing the surgery in 23% of them.[54]

Other inflammatory conditions of penile skin

Other penile skin disorders include psoriasis, penile infections, LS, lichen planus, seborrheic dermatitis, and Zoon (plasma cell) balanitis, as described in extensive reviews.[1,21,55] These conditions are either much more common in, or totally confined to, uncircumcised males. A total of 34 different conditions, most commonly lichenoid conditions (24%), followed by nonspecific balanitis (22%), eczema and psoriasis (11%), Zoon/plasma cell balanitis (10%), malignancy/premalignant change (10%), and infective conditions (9%), were diagnosed over a 3-year period in 226 men in a clinic in Edinburgh.[31] Penile dermatoses in general have been reported in 20,[56] 5,[57] 3,[31] and 2[30] times as many uncircumcised as circumcised men. Data on several of the most prominent conditions follow.

A large series has shown that all patients with Zoon balanitis, Bowenoid papulosis, and nonspecific balanoposthitis were uncircumcised.[30] Bowenoid papulosis occurs mainly in young sexually active men.[55] One Zoon balanitis case has been reported in a circumcised man.[58] Typical symptoms of Zoon balanitis are erythrema (always), swelling (in 91%), discharge (in 73%), dysuria (in 13%), bleeding (in 2%), and ulceration (in 1%).[21] Mycobacterium smegmatis has been implicated in Zoon balanitis.[1] Zoon balanitis in 112 uncircumcised men aged 24–70 years involved lesions on the foreskin and glans of 59%, foreskin only in 23%, and glans only in 18%.[59] Lesions associated with Zoon balanitis improved after treatment with 0.1% tacrolimus ointment.[60] Erosive lichen planus is associated with increased mast cells, foreskin scarring, and phimosis in uncircumcised men.[61]

Lichen sclerosus

Overview

LS (previously termed either LS et atrophicus or balanitis xerotica obliterans) is a chronic, progressive, sclerosing inflammatory anogenital skin disease of uncertain etiology.[1] Figure 4 shows typical clinical appearance.[62] It is mostly anogenital. Only about 10% of patients have extragenital involvement. Because LS is among the most serious penile inflammatory condition, it has generated numerous publications.

Figure 4.

Lichen sclerosus. (a) Appearance of foreskin and glans. (b) Meatal stricture which can result. Reprinted from Depasquale et al.[62]

Clinical presentation of lichen sclerosus

LS represents a challenge to urologists.[63] It presents as single or multiple erythematous papules, macules, or plaques that progress to sclerotic or atrophic white, ivory, or blue-white coalescent flat-topped papules and plaques.[1] Lesions commonly involve the glans and foreskin, although the frenulum, urethral meatus, and fossa navicularis may be involved as well. A sclerotic white ring at the tip of the foreskin is diagnostic of LS. Shaft and perianal involvement is rare. Serrous and hemorrhagic bullae, erosions, fissures, telangiectasia, and petechiae of the glans can occur. The foreskin may be adherent to the glans. As the disease progresses, the coronal sulcus and frenulum may be obliterated and the meatus gradually narrows. Progression of the disease through the entire urethra takes over 10 years,[64] resulting in significant urinary retention, followed by retrograde damage to the posterior urethra, bladder, and kidneys.[1] Eventual sloughing of the distal 0.5 cm of the urethra can occur.

LS can present at any age[65] and estimated prevalence is 1 in 300 to 1 in 1,000.[66] In prepubertal German boys, the prevalence was 0.1%–0.4%[67] and in Danish boys aged 1–17 years was 0.37%.[68]

LS is a common cause of phimosis in boys.[69,70] Early in its course, LS is often asymptomatic. Men may complain of phimosis, pruritis, burning, hypoesthesia of the glans, dysuria, urethritis with or without discharge, painful erections, and sexual dysfunction.[1] In a Swedish study, 56% of LS patients complained of an adverse effect on their sex lives.[71]

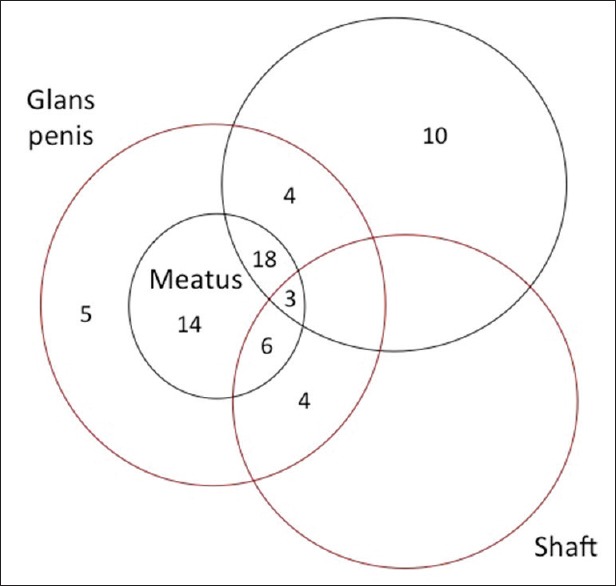

Figure 5 shows the penile sites affected by LS in a study of 66 men at a genitourinary clinic in Oxford, the UK.[65] Frequency was 64% for meatus (37% of these having meatal narrowing), 55% foreskin, 20% shaft, and 20% glans.[65] At the time of diagnosis, 30% of patients did not complain of symptoms related to LS. Nine percent had had a circumcision. A 2014 review of 40 reports found that LS affected the foreskin and glans in 57%–100% of cases, the meatus in 4%–37%, and urethra in 20%.[72] These studies found that disease progression may lead to phimosis and severe urethral stricture disease.[72] LS prevalence has generally been thought to peak in the fourth decade of life,[73] although a peak in the third decade has also been reported.[74] Foreskin biopsy after circumcision diagnosed LS histologically in 4%–19% of cases.[1,21] Because of the narrow foreskin opening, partial or complete urinary obstruction occurs. Both urethral stenosis and meatal stenosis is seen, so making LS a significant medical problem.[75,76]

Figure 5.

The penile sites affected by lichen sclerosus and the frequency of each in a study of 66 cases in the UK. Redrawn and slightly modified from Riddell et al.[65]

Etiology of lichen sclerosus

LS may have an autoimmune origin, exacerbated by the warm and moist subpreputial environment,[67] but genetic and hormonal factors[77] and the isomorphic response[1] probably contribute. Lack of circumcision applies to 98% of LS patients.[30] Postpubertal circumcision has also been invoked.[78]

Lichen sclerosus in boys

Rather than being rare, and a disorder presenting in adulthood, LS is now regarded as common in boys.[75,79,80] In boys, average age of diagnosis is 9–11 years.[81] Atopic skin diathesis, seen in 25% of juvenile cases, may predispose to LS.[82] In contrast to a reported rate of 1%,[83] two UK studies found LS prevalence of 5% and 6% in uncircumcised boys under 18 and 15 years of age, respectively.[84,85] Histological examination of foreskins removed for various reasons revealed LS in 3.6%–19%.[86,87,88,89,90,91] A study in Plymouth, UK, of 422 boys aged 3 months to 16 years (mean 6 years) referred to a pediatric general surgical outpatient department with foreskin problems found 55.9% were normal, with the remainder (44.1%) undergoing surgery: 35% circumcision, 8% preputial adhesiolysis, and 0.1% frenuloplasty.[75] Histological abnormalities were seen in 85% of the foreskins removed by circumcision; chronic inflammation was seen in 47%, LS in 35%, fibrosis in 3%, and 13% were histologically normal.[75]

Global LS prevalence from 13 studies was 35% in foreskins from boys circumcised for any reason.[92] A prospective study in Budapest involving 1,178 boys who presented consecutively over the decade 1991–2001 and who underwent circumcision, identified LS in 40% of histological specimens, with peak prevalence of 76% at ages 9–11 years.[93] In this study, 19% had an early, 60% had an intermediate, and 21% had a late form of LS.

LS prevalence in acquired phimosis cases ranges from 10%[94] to 80%–90%[67] in more recent studies. LS can cause pathological phimosis as a result of secondary cicatrization of the foreskin orifice. In one study, LS was regarded as responsible for secondary phimosis in all pediatric patients requiring circumcision.[93] In another study, 37% of pediatric patients with severe phimosis had LS.[95] A further study found LS in 60% of boys with acquired phimosis and in 30% of those with congenital phimosis.[96] Foreskin inflammation was seen in 88% and 82%, respectively. The study also examined boys with congenital hypospadias, with 61% showing symptoms of inflammation and 15% having features consistent with LS. In a case series from Boston, of 41 pediatric patients with LS, 52% had been referred for phimosis, 13% for balanitis, and 10% for buried penis.[97]

Lichen sclerosus in adult males

An Italian study of men of mean age 46 years found LS in 85% of biopsies, LS of the foreskin being documented by histology in 93% of cases, of the meatus in 92% of cases, of the fossa navicularis in 84% and of the penile urethra in 71%.[64] A Hungarian study of men circumcised for phimosis found LS in 62%.[98]

In older patients, progressive LS or other inflammatory changes can lead to phimosis.[99] LS with phimosis can also cause lower urinary tract symptoms in elderly men.[100] Phimosis in older men is associated with 44%–85% of cases of penile cancer.[72,101] In men not circumcised in childhood, phimosis was strongly associated with invasive penile cancer, as was high-risk HPV.[102] Oncogenic HPV was seen in 23% of 92 Italian men aged on average 68 years who had LS, compared to 15% of men aged on average 58 years without LS, suggesting that LS causes slower clearance of HPV.[103] Among 226 males aged 16–95 years attending a penile dermatology clinic in Edinburgh, penile intraepithelia neoplasia was diagnosed in 6% and invasive penile cancer in 2%.[31] Penile cancer was seen in 1% of 771 Swedish men aged 48.6 years (range 22–92) diagnosed with LS during 1997–2007.[71] Another study found penile cancer in 4%–8% of men with LS.[104]

A random-effects meta-analysis of 8 studies found an association of phimosis with a 12-fold (95% CI 5.6–26) increase in penile cancer risk.[105] Lifetime prevalence of penile cancer is approximately 1 in 1000.[7,8,105] Among patients diagnosed with LS, penile cancer occurred in 2.3%–8.4% and mean time between diagnosis of LS and development of penile cancer is 12 years.[62,72,106]

LS represents an important, potentially preventable risk factor for this devastating cancer.

Treatment of lichen sclerosus in boys

The treatment of choice for LS in boys is circumcision.[62,93,94] Conservative treatment with topical steroids is considered “controversial.”[67,82] Because of significant side effects, steroid use should be avoided in children.[72] Preputioplasty is regarded by some as effective, although 13% of patients developed recurrent symptoms.[107] Preputioplasty or frenuloplasty are never a first choice. They are only an option when parents do not agree to circumcise. A Boston study found 46% of pediatric LS patients underwent curative circumcision.[97] In 27%, LS involved the meatus, so besides circumcision these patients had meatotomy or meatoplasty. In all, 22% required extensive plastic surgery of the penis, including buccal mucosa grafts, demonstrating a more severe and morbid clinical course. A study in Liverpool, UK, of 300 boys (mean age 9 years; range 4–16 years) circumcised after clinical diagnosis of LS, confirmed LS by histology in 80% and 1 in 5 required subsequent meatal dilatation or meatotomy for meatal pathology.[108]

Treatment of lichen sclerosus in men

Circumcision is curative in “nearly 100%” of LS cases.[109] Another study reported a cure rate of over 75%[73] and when confined to the foreskin, circumcision resulted in a long-term cure in 92% of LS patients.[62]

Steroid creams can limit disease progression but do not cure many LS cases.[73,110] Steroids lead to an improvement in 41%–76%, but a cure in only 50%–60% of cases in men.[73] In the second author's experience, steroids are less effective than this. Recurrence of LS after steroid treatment may occur after 5 years.[109] In a Swedish study, 30% of men reported that outcome of local steroid treatment was “good,” while 37% said it was “medium” and 16% “poor” (17% failed to answer).[71] An Indian study of men aged 20–45 years with LS reported a preference by all for circumcision rather than use of steroid creams.[111] In another Indian study, 77% received circumcision for treatment.[63]

Progression to urethral involvement makes treatment much more difficult.[72] Treatment may include meatotomy or meatoplasty for meatal stenosis and urethroplasty for urethral involvement. Extensive disease affecting the full length of the urethra may require perineal urethrostomy.[72] In an Italian study of men of mean age 46 years, treatment included circumcision, meatotomy, navicularis uroplasty, extensive grafting procedures, and perineal urethrostomy.[64]

Conclusions

Balanitis and balanoposthitis are common. Not only do they lead to frequent medical consultations, but if not treated, the consequences can include acquired phimosis and LS, the treatment of which can often be challenging. While topical antifungal creams can be used to treat each of these, usually accompanied by advice on hygiene, the definitive treatment is circumcision. Based on the evidence, circumcision of males, particularly early in life, substantially reduced the risk of penile inflammatory conditions. The clinical and personal burden of penile inflammatory conditions in males can be ameliorated by preventive measures, most notably circumcision.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.English JC, 3rd, Laws RA, Keough GC, Wilde JL, Foley JP, Elston DM. Dermatoses of the glans penis and prepuce. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:1–24. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.West DS, Papalas JA, Selim MA, Vollmer RT. Dermatopathology of the foreskin: An institutional experience of over 400 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:11–8. doi: 10.1111/cup.12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards S. Balanitis and balanoposthitis: A review. Genitourin Med. 1996;72:155–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.72.3.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NA, Levitz SM, Netea MG, White TC. Hidden killers: Human fungal infections. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:165rv13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moyes DL, Wilson D, Richardson JP, Mogavero S, Tang SX, Wernecke J, et al. Candidalysin is a fungal peptide toxin critical for mucosal infection. Nature. 2016;532:64–8. doi: 10.1038/nature17625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Severance EG, Gressitt KL, Stallings CR, Katsafanas E, Schweinfurth LA, Savage CL, et al. Candida albicans exposures, sex specificity and cognitive deficits in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. NPJ Schizophr. 2016;2:16018. doi: 10.1038/npjschz.2016.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision. Male circumcision. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e756–85. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Docket No. CDC-2014-0012-0002] Recommendations for Providers Counseling Male Patients and Parents Regarding Male Circumcision and the Prevention of HIV Infection, STIs, and Other Health Outcomes. 2014. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 14]. Available from: http://www.regulations.gov/-!documentDetail;D=CDC-2014-0012-0002 .

- 9.American Urological Association. Circumcision. [Last accessed on 2016 Sep 14]. Available from: http://www.auanet.org/about/policy-statements/circumcision.cfm .

- 10.Morris BJ, Wodak AD, Mindel A, Schrieber L, Duggan KA, Dilly A, et al. Infant male circumcision: An evidence-based policy statement. Open J Prevent Med. 2012;2:79–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2012.02823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aridogan IA, Izol V, Ilkit M. Superficial fungal infections of the male genitalia: A review. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2011;37:237–44. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2011.572862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.David LM, Walzman M, Rajamanoharan S. Genital colonisation and infection with Candida in heterosexual and homosexual males. Genitourin Med. 1997;73:394–6. doi: 10.1136/sti.73.5.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiumara NJ, Kahn S. Contact dermatitis from a gonococcal discharge: A case report. Sex Transm Dis. 1982;9:41–2. doi: 10.1097/00007435-198201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dawson SG, Ison CA, Csonka G, Easmon CS. Male carriage of Gardnerella vaginalis. Br J Vener Dis. 1982;58:243–5. doi: 10.1136/sti.58.4.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwebke JR, Rivers C, Lee J. Prevalence of Gardnerella vaginalis in male sexual partners of women with and without bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:92–4. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181886727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Escala JM, Rickwood AM. Balanitis. Br J Urol. 1989;63:196–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1989.tb05164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ladenhauf HN, Ardelean MA, Schimke C, Yankovic F, Schimpl G. Reduced bacterial colonisation of the glans penis after male circumcision in children – A prospective study. J Pediatr Urol. 2013;9(6 Pt B):1137–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herzog LW, Alvarez SR. The frequency of foreskin problems in uncircumcised children. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140:254–6. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1986.02140170080036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fergusson DM, Lawton JM, Shannon FT. Neonatal circumcision and penile problems: An 8-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 1988;81:537–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fakjian N, Hunter S, Cole GW, Miller J. An argument for circumcision. Prevention of balanitis in the adult. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1046–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Köhn FM, Pflieger-Bruss S, Schill WB. Penile skin diseases. Andrologia. 1999;31(Suppl 1):3–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1999.tb01443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Orden B, Martin R, Franco A, Ibañez G, Mendez E. Balanitis caused by group A beta-hemolytic streptococci. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:920–1. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199610000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lucks DA, Venezio FR, Lakin CM. Balanitis caused by group B streptococcus. J Urol. 1986;135:1015. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45963-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laway MA, Wani ML, Patnaik R, Kakru D, Ismail S, Shera AH, et al. Does circumcision alter the periurethral uropathogenic bacterial flora. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2012;9:109–12. doi: 10.4103/0189-6725.99394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anyanwu LJ, Kashibu E, Edwin CP, Mohammad AM. Microbiology of smegma in boys in Kano, Nigeria. J Surg Res. 2012;173:21–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balci M, Tuncel A, Baran I, Guzel O, Keten T, Aksu N, et al. High-risk oncogenic human papilloma virus infection of the foreskin and microbiology of smegma in prepubertal boys. Urology. 2015;86:368–72. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarhan H, Akarken I, Koca O, Ozgü I, Zorlu F. Effect of preputial type on bacterial colonization and wound healing in boys undergoing circumcision. Korean J Urol. 2012;53:431–4. doi: 10.4111/kju.2012.53.6.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mousavi SA, Shokohi T, Hedayati MT, Mosayebi E, Abdollahi A, Didehdar M. Prevalence of yeast colonization on prepuce of uncircumcised children. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2015;25:118–22. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iskit S, Ilkit M, Turç-Biçer A, Demirhindi H, Türker M. Effect of circumcision on genital colonization of Malassezia spp. in a pediatric population. Med Mycol. 2006;44:113–7. doi: 10.1080/13693780500225919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mallon E, Hawkins D, Dinneen M, Francics N, Fearfield L, Newson R, et al. Circumcision and genital dermatoses. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:350–4. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.3.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pearce J, Fernando I. The value of a multi-specialty service, including genitourinary medicine, dermatology and urology input, in the management of male genital dermatoses. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26:716–22. doi: 10.1177/0956462414552695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lisboa C, Ferreira A, Resende C, Rodrigues AG. Infectious balanoposthitis: Management, clinical and laboratory features. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:121–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krieger JN, Mehta SD, Bailey RC, Agot K, Ndinya-Achola JO, Parker C, et al. Adult male circumcision: Effects on sexual function and sexual satisfaction in Kisumu, Kenya. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2610–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00979.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bromage SJ, Crump A, Pearce I. Phimosis as a presenting feature of diabetes. BJU Int. 2008;101:338–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patton JF. Urology. In United States Army Surgery in World War II. Office of the Surgeon General and Center of Military History. 1987:45–88. 52, 64, 100, 120, 121, 145, 146, 183, 488. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schneider JA, Vadivelu S, Liao C, Kandukuri SR, Trikamji BV, Chang E, et al. Increased likelihood of bacterial pathogens in the coronal sulcus and urethra of uncircumcised men in a diverse group of HIV infected and uninfected patients in India. J Glob Infect Dis. 2012;4:6–9. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.93750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayser P, Schütz M, Schuppe HC, Jung A, Schill WB. Frequency and spectrum of Malassezia yeasts in the area of the prepuce and glans penis. BJU Int. 2001;88:554–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aridogan IA, Ilkit M, Izol V, Ates A, Demirhindi H. Glans penis and prepuce colonisation of yeast fungi in a paediatric population: Pre- and postcircumcision results. Mycoses. 2009;52:49–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu CM, Hungate BA, Tobian AA, Ravel J, Prodger JL, Serwadda D, et al. Penile microbiota and female partner bacterial vaginosis in Rakai, Uganda. MBio. 2015;6:e00589. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00589-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Nalugoda F, Watya S, et al. The effects of male circumcision on female partners’ genital tract symptoms and vaginal infections in a randomized trial in Rakai, Uganda. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:42.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.07.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Price LB, Liu CM, Johnson KE, Aziz M, Lau MK, Bowers J, et al. The effects of circumcision on the penis microbiome. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu CM, Hungate BA, Tobian AA, Serwadda D, Ravel J, Lester R, et al. Male circumcision significantly reduces prevalence and load of genital anaerobic bacteria. MBio. 2013;4:e00076. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00076-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nelson DE, Dong Q, Van der Pol B, Toh E, Fan B, Katz BP, et al. Bacterial communities of the coronal sulcus and distal urethra of adolescent males. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Farrell N, Quigley M, Fox P. Association between the intact foreskin and inferior standards of male genital hygiene behaviour: A cross-sectional study. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:556–9. doi: 10.1258/0956462054679151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilson RA. Circumcision and venereal disease. Can Med Assoc J. 1947;56:54–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor PK, Rodin P. Herpes genitalis and circumcision. Br J Vener Dis. 1975;51:274–7. doi: 10.1136/sti.51.4.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morris BJ, Waskett JH, Banerjee J, Wamai RG, Tobian AA, Gray RH, et al. A ‘snip’ in time: What is the best age to circumcise? BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-12-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edwards SK, Bunker CB, Ziller F, van der Meijden WI. 2013 European guideline for the management of balanoposthitis. Int J STD AIDS. 2014;25:615–26. doi: 10.1177/0956462414533099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schoen EJ. Circumcision as a lifetime vaccination with many benefits. J Mens Health Gend. 2007;382:306–11. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kinghorn GR, Jones BM, Chowdhury FH, Geary I. Balanoposthitis associated with Gardnerella vaginalis infection in men. Br J Vener Dis. 1982;58:127–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.58.2.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Romero FR, Romero AW, Almeida RM, Oliveira FC, Jr, Filho RT., Jr Prevalence and risk factors for penile lesions/anomalies in a cohort of Brazilian men ≥40 years of age. Int Braz J Urol. 2013;39:55–62. doi: 10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2013.01.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verma SB, Wollina U. Looking through the cracks of diabetic candidal balanoposthitis! Int J Gen Med. 2011;4:511–3. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S17875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwartz RH, Rushton HG. Acute balanoposthitis in young boys. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996;15:176–7. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199602000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wiswell TE, Tencer HL, Welch CA, Chamberlain JL. Circumcision in children beyond the neonatal period. Pediatrics. 1993;92:791–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh S, Bunker C. Male genital dermatoses in old age. Age Ageing. 2008;37:500–4. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Samuel M, Brady M, Tenant-Flowers M, Taylor C. Role of penile biopsy in the diagnosis of penile dermatoses. Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21:371–2. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.009568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.David N, Tang A. Efficacy and safety of penile biopsy in a GUM clinic setting. Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13:573–6. doi: 10.1258/095646202760159729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Toker SC, Baskan EB, Tunali S, Yilmaz M, Karadogan SK. Zoon's balanitis in a circumcised man. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(2 Suppl):S6–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kumar B, Narang T, Dass Radotra B, Gupta S. Plasma cell balanitis: Clinicopathologic study of 112 cases and treatment modalities. J Cutan Med Surg. 2006;10:11–5. doi: 10.1007/7140.2006.00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moreno-Arias GA, Camps-Fresneda A, Llaberia C, Palou-Almerich J. Plasma cell balanitis treated with tacrolimus 0.1% Br J Dermatol. 2005;153:1204–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Regauer S, Beham-Schmid C. Benign mast cell hyperplasia and atypical mast cell infiltrates in penile lichen planus in adult men. Histol Histopathol. 2014;29:1017–25. doi: 10.14670/HH-29.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Depasquale I, Park AJ, Bracka A. The treatment of balanitis xerotica obliterans. BJU Int. 2000;86:459–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Singh JP, Priyadarshi V, Goel HK, Vijay MK, Pal DK, Chakraborty S, et al. Penile lichen sclerosus: An urologist's nightmare! – A single center experience. Urol Ann. 2015;7:303–8. doi: 10.4103/0974-7796.150490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barbagli G, Mirri F, Gallucci M, Sansalone S, Romano G, Lazzeri M. Histological evidence of urethral involvement in male patients with genital lichen sclerosus: A preliminary report. J Urol. 2011;185:2171–6. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Riddell L, Edwards A, Sherrard J. Clinical features of lichen sclerosus in men attending a department of genitourinary medicine. Sex Transm Infect. 2000;76:311–3. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.4.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:9–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Becker K. Lichen sclerosus in boys. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108:53–8. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2011.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sneppen I, Thorup J. Foreskin morbidity in uncircumcised males. Pediatrics. 2016;137 doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-4340. pii: e20154340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rickwood AM, Hemalatha V, Batcup G, Spitz L. Phimosis in boys. Br J Urol. 1980;52:147–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1980.tb02945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Garat JM, Chéchile G, Algaba F, Santaularia JM. Balanitis xerotica obliterans in children. J Urol. 1986;136:436–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)44895-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kantere D, Löwhagen GB, Alvengren G, Månesköld A, Gillstedt M, Tunbäck P. The clinical spectrum of lichen sclerosus in male patients – A retrospective study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:542–6. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stewart L, McCammon K, Metro M, Virasoro R. SIU/ICUD Consultation on Urethral Strictures: Anterior urethra-lichen sclerosus. Urology. 2014;83(Suppl):S27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Edmonds EV, Hunt S, Hawkins D, Dinneen M, Francis N, Bunker CB. Clinical parameters in male genital lichen sclerosus: A case series of 329 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:730–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kizer WS, Prarie T, Morey AF. Balanitis xerotica obliterans: Epidemiologic distribution in an equal access health care system. South Med J. 2003;96:9–11. doi: 10.1097/00007611-200301000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yardley IE, Cosgrove C, Lambert AW. Paediatric preputial pathology: Are we circumcising enough? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:62–5. doi: 10.1308/003588407X160828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Belsante MJ, Selph JP, Peterson AC. The contemporary management of urethral strictures in men resulting from lichen sclerosus. Transl Androl Urol. 2015;4:22–8. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.01.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393–416. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(95)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weigand DA. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, multiple dysplastic keratoses, and squamous-cell carcinoma of the glans penis. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1980;6:45–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1980.tb00808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Jayakumar S, Antao B, Bevington O, Furness P, Ninan GK. Balanitis xerotica obliterans in children and its incidence under the age of 5 years. J Pediatr Urol. 2012;8:272–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kuehhas FE, Miernik A, Weibl P, Schoenthaler M, Sevcenco S, Schauer I, et al. Incidence of balanitis xerotica obliterans in boys younger than 10 years presenting with phimosis. Urol Int. 2013;90:439–42. doi: 10.1159/000345442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: An update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27–47. doi: 10.1007/s40257-012-0006-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Becker K, Meissner V, Farwick W, Bauer R, Gaiser MR. Lichen sclerosus and atopy in boys: Coincidence or correlation? Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:362–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rickwood AM, Kenny SE, Donnell SC. Towards evidence based circumcision of English boys: Survey of trends in practice. BMJ. 2000;321:792–3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7264.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Griffiths D, Frank JD. Inappropriate circumcision referrals by GPs. J R Soc Med. 1992;85:324–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Huntley JS, Bourne MC, Munro FD, Wilson-Storey D. Troubles with the foreskin: One hundred consecutive referrals to paediatric surgeons. J R Soc Med. 2003;96:449–51. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.96.9.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bainbridge DR, Whitaker RH, Shepheard BG. Balanitis xerotica obliterans and urinary obstruction. Br J Urol. 1971;43:487–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1971.tb12073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schinella RA, Miranda D. Posthitis xerotica obliterans in circumcision specimens. Urology. 1974;3:348–51. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(74)80120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ridley CM. Genital lichen sclerosus (lichen sclerosus et atrophicus) in childhood and adolescence. J R Soc Med. 1993;86:69–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chalmers RJ, Burton PA, Bennett RF, Goring CC, Smith PJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. A common and distinctive cause of phimosis in boys. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1025–7. doi: 10.1001/archderm.120.8.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bale PM, Lochhead A, Martin HC, Gollow I. Balanitis xerotica obliterans in children. Pediatr Pathol. 1987;7:617–27. doi: 10.3109/15513818709161425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Clemmensen OJ, Krogh J, Petri M. The histologic spectrum of prepuces from patients with phimosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:104–8. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198804000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Celis S, Reed F, Murphy F, Adams S, Gillick J, Abdelhafeez AH, et al. Balanitis xerotica obliterans in children and adolescents: A literature review and clinical series. J Pediatr Urol. 2014;10:34–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kiss A, Király L, Kutasy B, Merksz M. High incidence of balanitis xerotica obliterans in boys with phimosis: Prospective 10-year study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:305–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2005.22404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Meuli M, Briner J, Hanimann B, Sacher P. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus causing phimosis in boys: A prospective study with 5-year followup after complete circumcision. J Urol. 1994;152:987–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32638-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rossi E, Pavanello P, Franchella A. Lichen sclerosus in children with phimosis. Minerva Pediatr. 2007;59:761–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mattioli G, Repetto P, Carlini C, Granata C, Gambini C, Jasonni V. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus in children with phimosis and hypospadias. Pediatr Surg Int. 2002;18:273–5. doi: 10.1007/s003830100699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Gargollo PC, Kozakewich HP, Bauer SB, Borer JG, Peters CA, Retik AB, et al. Balanitis xerotica obliterans in boys. J Urol. 2005;174(4 Pt 1):1409–12. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000173126.63094.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nyirády P, Borka K, Bánfi G, Kelemen Z. Lichen sclerosus in urological practice. Orv Hetil. 2006;147:2125–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Aynaud O, Piron D, Casanova JM. Incidence of preputial lichen sclerosus in adults: Histologic study of circumcision specimens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:923–6. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70247-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nemoto K, Ishidate T. Balanitis xerotica obliterans with phimosis in elderly patients presenting with difficulty in urination. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2013;59:341–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Micali G, Nasca MR, Innocenzi D, Schwartz RA. Penile cancer. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:369–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Daling JR, Madeleine MM, Johnson LG, Schwartz SM, Shera KA, Wurscher MA, et al. Penile cancer: Importance of circumcision, human papillomavirus and smoking in in situ and invasive disease. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:606–16. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nasca MR, Lacarrubba F, Paravizzini G, Micali G. Oncogenic human papillomavirus detection in penile lichen sclerosis: An update. Int STD Res Rev. 2014;2:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Clouston D, Hall A, Lawrentschuk N. Penile lichen sclerosus (balanitis xerotica obliterans) BJU Int. 2011;108(Suppl 2):14–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Morris BJ, Gray RH, Castellsague X, Bosch FX, Halperin DT, Waskett JH, et al. The strong protective effect of circumcision against cancer of the penis. Adv Urol 2011. 2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/812368. 812368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Barbagli G, Palminteri E, Mirri F, Guazzoni G, Turini D, Lazzeri M. Penile carcinoma in patients with genital lichen sclerosus: A multicenter survey. J Urol. 2006;175:1359–63. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00735-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wilkinson DJ, Lansdale N, Everitt LH, Marven SS, Walker J, Shawis RN, et al. Foreskin preputioplasty and intralesional triamcinolone: A valid alternative to circumcision for balanitis xerotica obliterans. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:756–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Homer L, Buchanan KJ, Nasr B, Losty PD, Corbett HJ. Meatal stenosis in boys following circumcision for lichen sclerosus (balanitis xerotica obliterans) J Urol. 2014;192:1784–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kirtschig G, Becker K, Günthert A, Jasaitiene D, Cooper S, Chi CC, et al. Evidence-based (S3) guideline on (anogenital) lichen sclerosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:e1–43. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hartley A, Ramanathan C, Siddiqui H. The surgical treatment of Balanitis Xerotica Obliterans. Indian J Plast Surg. 2011;44:91–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.81455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Singh Thakur R, Pinjala P, Babu M. Balanitis xerotica obliterans Bxo-mimicking vitiligo. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2015;14:29–31. [Google Scholar]