The Society of Rural Physicians of Canada (SRPC) recognizes the importance of educating physicians for rural practice. Because students with a rural background are the most likely to ultimately choose rural practice as a career, achieving an adequate supply of rural physicians depends in part on ensuring the admission of an adequate number of students of rural origin to medical school. National data published in 20021 revealed that students of rural origin are seriously underrepresented in Canadian medical schools. This finding prompted the formation of a national task force to address the issue. A large number of physicians volunteered to become involved, enabling the formation of a core national committee and a larger interest group. In addition, 3 focus group sessions were held, and over 100 submissions were received from individuals and groups. A survey of Canadian medical school associate deans was also conducted to determine the current status of rural admission initiatives and strategies. In presenting these recommendations, the SRPC task force hopes that policies, strategies, initiatives and funding can be implemented to increase the number of medical students of rural origin to a fair and equitable level, and that this will ultimately lead to increased numbers of medical school graduates who choose a career in rural practice.

Canada, with 10 million square kilometres, is the second largest country in the world but has a population of only 30 million people. Depending on the definition of “rural” that is used, between 21% and 38% of Canadians live in rural areas.2 The geographic realities of time and distance combined with limited or distant specialist and high-tech resources makes the provision of health care services in rural areas a difficult challenge. An adequate supply of well-trained rural physicians is essential to the provision of accessible, high-quality rural health care.

Canada is facing a shortage of family physicians and specialists in rural practice. Using the Statistics Canada definition of “rural” and “small town,” currently 22% of the population of Canada is rural, as are 17.1% of family physicians and 2.8% of specialists. The family physician–population ratio in rural Canada in 2002 was 1:1201, as compared with 1:981 for Canada as a whole; to put it another way, 1175 additional family physicians are needed in rural areas to bring the family physician–population ratio to the same level as the Canadian average. This does not include the needs of rural communities within the commuting zone of urban centres. As of 2002, only 75 of the 711 physicians who had graduated from family medicine training programs in 2000 had entered rural practice. (Calculations based on the CMA physician database information from Lynda Buske, Associate Director, Research, CMA: personal communication, 2003). The developing shortage of family physicians in all practice settings in Canada will only make the situation worse.3,4

Studies in Canada and elsewhere indicate that rural physicians are up to 5 times more likely than their urban counterparts to come from a rural background.5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 A recent study in Ontario found that one-third of rural physicians came from a rural background.6Woloschuk and Tarrant18 reported that Canadian clerkship students of rural origin were significantly more likely than their peers raised in urban areas to indicate that they planned to do rural locums and to practise in rural communities. This student cohort was followed into practice; of those who completed family medicine residency training, those with a rural background were 2.5 times more likely to be engaged in rural practice than their urban peers.19 On entry into medical school, Canadian students from smaller communities are also more likely than their counterparts from large urban communities to indicate a preference for family practice as a career choice.20 This is important in the context of the dramatic decline in the number of graduating medical students who chose family medicine residencies from 44% in 1992 to 25% in 2003.21

Although having a rural background clearly influences the eventual choice of a rural area as the setting of practice, the fact remains that most medical students come from urban areas; hence, a significant portion of rural physicians do and will need to come from urban backgrounds. Longer rural learning experiences in medical school and postgraduate family medicine training are associated with a significantly higher likelihood of choosing rural practice, regardless of whether the graduate's background is urban or rural.6 More detailed discussions of Canadian medical education for rural practice can be found in a report by the College of Family Physicians of Canada Working Group on Postgraduate Education for Rural Family Practice.22

The present article focuses on admission and preadmission initiatives related to medical students of rural origin. A 2001 survey found that only 10.8% of Canadian medical students lived in rural areas at high school graduation, as compared with 22.4% of the population.1 In a survey of medical school associate deans responsible for admissions conducted in 2003 by the SRPC task force, none reported a percentage of medical students of rural origin in their school that matched the percentage of rural residents in their province overall. National data on applicants, including grade point averages and offers of admission, are not available, but Ontario data suggest that fewer rural students than urban students apply to medical school and that, even of those who do apply, fewer are accepted even when their grade point averages and MCAT scores are similar to those of their urban counterparts.23

Dhalla and colleagues1 found that medical students were more likely than the general Canadian population to have parents who were highly educated professionals. On average, people living in rural communities have a lower educational status than their urban counterparts;24 as a result, young people growing up in rural communities may have fewer role models, less encouragement and experience less acceptance than their urban peers with respect to pursuing higher education, including medical school. Even rural students with a parent with a degree are much less likely to attend university than their urban counterparts (25.8% v. 43.2%).25

Many rural high schools can provide neither the breadth nor the depth of academic programs and enrichment activities that are available to urban high school students. In particular, opportunities to participate in provincial or national level activities are often significantly fewer for rural students than for their urban peers. This is not only a direct educational disadvantage, but it can also be a disadvantage when rural students' curricula vitae are assessed against those of their urban counterparts. Rurality also presents a disadvantage with respect to access to technology. For example, “[r]ural individuals … within each age class within each income class … within each educational attainment class, are less likely to own a computer or to be connected to the Internet.”26

Rural students by necessity have to travel away from home to attend university — another factor that contributes to the smaller number of students from rural areas who attend university.25 This geographic barrier is extreme for Canada's most isolated rural people — those in Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, the Yukon and remote parts of many provinces — and includes many Aboriginal Canadians, who face additional linguistic and cultural barriers.

The fact that rural students do not have the option of getting an undergraduate degree in their home town results in costs for accommodation and other living expenses that many urban students do not have to bear. Medical students typically come from families with high incomes.1 Rural families are significantly poorer than their urban counterparts,24 and the high cost of medical education is a higher perceived and real barrier for rural students than for urban students. Rural students in medical school have a higher debt load and increased financial anxiety compared with their urban counterparts.

The medical school admission process may be unintentionally biased and difficult for rural medical students. Only 3 respondents to the SRPC task force survey of Canadian medical school associate deans indicated that they had a rural physician on their school's admission committee. It is difficult to develop policies that take rural issues into account if there is no rural representation on the admission committee. Similarly, the preponderance of urban interviewers at most medical schools may result in an unintentional urban selection bias; it may be that “medical school admission committee members tend to give high ratings to those students whose backgrounds, values and orientation are similar to their own.”27 Again, in the task force survey, only 3 respondents indicated that their schools had a specific policy or strategy for admitting students of rural origin. Given Canada's continuing and worsening shortage of rural physicians, this reflects an unfortunate lack of attention to the low numbers of rural students being admitted to medical schools, as well as a lack of attention to issues that can have a direct impact on the capacity of the physician workforce to meet the needs of the Canadian population. Moreover, the trend to higher and higher grade point averages and MCAT scores, together with rapidly rising tuition fees, may put admission to medical school beyond the reach of all but a very few Canadian students with rural backgrounds.

Positive change is possible. In Australia, the number of medical students from rural areas increased from 10% in 1989 to 25% in 2000. This change came about through a series of initiatives, including bursaries, scholarships and policy changes, such as creating new spots for students of rural origin.28 In the United States, surveys of the Association of American Medical Colleges found that “more than 60% of responding medical schools offered extra consideration at some point in the admissions process to candidates likely to enter primary care and rural applicants were frequently listed as one of these groups.”29 Moreover, one representative medical school calculated that there would have been a “marked reduction [to less than half] in the proportion of rural applicants offered admission interviews if additional consideration and score adjustment were not applied.”29

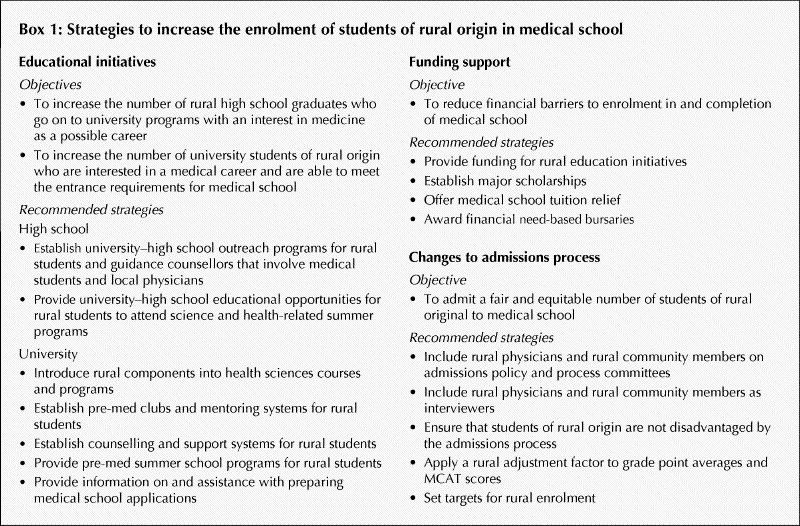

The SRPC hopes that the recommendations presented here (see Box 1 and the online appendix [www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/full/172/1/62/DC1]) will lead to the implementation of policies, initiatives and funding to increase the number of students from rural backgrounds admitted to medical school and ultimately produce more graduates who choose a career in rural practice. Outcomes research should be a critical component of these strategies. Medical schools will need to take the lead and work with universities, governments and other stakeholders to develop, coordinate and support programs to achieve the goal of admitting a fair and equitable number of rural origin students to Canadian medical schools.

Box 1.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The full report as approved by the SRPC is available at www.srpc.ca.

Contributors: Each task force member contributed substantially to the conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, helped draft or revise the report critically for important intellectual content and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. James Rourke, Dean of Medicine, Health Sciences Centre, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 300 Prince Philip Dr., St. John's NL A1B 3V6; dean.medicine@mun.ca

References

- 1.Dhalla IA, Kwong JC, Streiner DL, Baddour RE, Waddell AE, Johnson IL, et al. Characteristics of first-year students in Canadian medical schools. CMAJ 2002;166(8):1029-35. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Du Plessis V, Beshiri R, Bollman D, Clemenson H. Definitions of rural. Rural Small Town Canada Analysis Bull 2001;3(3):1-13. [Statistics Canada cat no 21-006-XIE]

- 3.Romanow RJ. Romanow RJ. Building on values: the future of health care in Canada: final report. Saskatoon: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2002. Available: www.healthcarecommission.ca (accessed 2004 Nov 15).

- 4.Health Canada. Health human resources: balancing supply and demand. Health Policy Res Bull 2004;8. Available:www.hc-sc.gc.ca/iacb-dgiac/arad-draa/english/rmdd/bulletin/ehuman.html (accessed 2004 Nov 15).

- 5.Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Hojat M, Hazelwood CE. Demographic, educational and economic factors related to recruitment and retention of physicians in rural Pennsylvania. J Rural Health 1999;15:212-28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Rourke JTB, Incitti F, Rourke LL, Kennard M. The relationship between practice location of family physicians in Ontario and rural background and rural medical education. Can J Rural Med. In press. [PubMed]

- 7.Brooks RG, Mardon R, Clawson A. The rural physician workforce in Florida: a survey of US- and foreign-born primary care physicians. J Rural Health 2003; 19(4):484-91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Laven GA, Beilby JJ, Wilkinson D, McElroy HJ. Factors associated with rural practice among Australian-trained general practitioners. Med J Aust 2003; 179 (2): 75-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Wilkinson D, Laven G, Pratt N, Beilby J. Impact of undergraduate and postgraduate rural training, and medical school entry criteria on rural practice among Australian general practitioners: a national study of 2414 doctors. Med Educ 2003;37:809-14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Paynter NP. Critical factors for designing programs to increase the supply and retention of rural primary care physicians. JAMA 2001;286:1041-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Easterbrook M, Godwin M, Wilson R, Hodgetts G, Brown G, Pong R, et al. Rural background and clinical rotations during medical training: effect on practice location. CMAJ 1999;160(8):1159-63. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Fryer GE Jr, Stine C, Vojir C, Miller M. Predictors and profiles of rural versus urban family practice. Fam Med 1997;29(2):115-8. [PubMed]

- 13.Canadian Medical Association. Report of the Advisory Panel on the Provision of Medical Services in Underserviced Regions. Ottawa: The Association; 1992.

- 14.Strasser RP. Attitudes of Victorian rural GPs to country practice and training. Aust Fam Physician 1992;21:808-12. [PubMed]

- 15.Stratton TD, Geller JM, Ludtke RL, Fichenscher KM. Effects of an expanded medical curriculum on the number of graduates practicing in a rural state. Acad Med 1991;66:101-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Rabinowitz HK. Relationship between US medical school admission policy and graduates entering family practice. Fam Practice 1988;5(2):1442-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Carter RG. The relation between personal characteristics of physicians and practice location in Manitoba. CMAJ 1987;136(4):366-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Woloschuk W, Tarrant M. Does a rural educational experience influence students' likelihood of rural practice? Impact of student background and gender. Med Educ 2002;36:241-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Woloschuk W, Tarrant M. Do students from rural backgrounds engage in rural family practice more than their urban raised peers? Med Educ 2004; 38: 259-61. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Wright B, Scott I, Woloschuk W, Brenneis F. Career choice of new medical students at three Canadian universities: family medicine versus specialty medicine. CMAJ 2004;170(13):1920-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Banner S. Canadian Resident Matching Service (CaRMS): PGY-1 2003 match report. Ottawa: Canadian Resident Matching Service. Available: www.carms.ca/jsp/main.jsp?path=../content/statistics/report/re_2003 (accessed 2004 Nov 15).

- 22.College of Family Physicians of Canada Working Group on Postgraduate Education for Rural Family Practice. Postgraduate education for rural family practice: vision and recommendations for the new millennium. Can Fam Physician 1999;45:2698-704. Available: www.cfpc.ca/English/cfpc/education/rural/Postgraduate%20Education%20for%20Rural%20Family%20Practice/default.asp?s=1#Working%20Group (accessed 2004 Nov 26). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Hutten-Czapski P, Pitblado R, Rourke J. Who gets into medical school? Ontario rural–urban comparisons. Canadian Family Physician. In press. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Du Plessis V, Beshiri R, Bollman D, Clemenson H. Definitions of rural. Rural Small Town Canada Analysis Bull 2001;3(3):15. Appendix Table A2. [Statistics Canada cat no 21-006-XIE]

- 25.Frenette M. Too far to go on? Distance to school and university participation [Analytical Studies Research Paper Series]. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2002. Cat no 11F0019MIE2002191. Available: www.statcan.ca/english/research/11F0019MIE/11F0019MIE2002191.pdf (accessed 2004 Nov 29).

- 26.Singh V. Factors associated with household internet use. Rural Small Town Canada Analysis Bull 2004:5:1. [Statistics Canada cat no 21-0006-XIE]

- 27.Urbina C, Hickey MN, McHarney-Brown C, Duban S, Kaufman A. Innovative generalist programs: academic health care centers respond to the shortage of generalist physicians. J Gen Intern Med 1994;9(Suppl 1): S81-S89. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Dunbabin J, Levitt L. Rural origin and rural medical exposure: their impact on the rural and remote medical workforce in Australia. Rural Remote Health [online journal] 2003;3(1):article 212. Available: http://rrh.deakin.edu.au (published 2003 June 23; accessed 2004 Nov 29). [PubMed]

- 29.Basco WT Jr, Gilbert GE, Blue AV. Determining the consequences for rural applicants when additional consideration is discontinued in a medical school admission process. Acad Med 2002;77(10 Suppl):S20-S22. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.