Abstract

HYPERHIDROSIS, A CONDITION CHARACTERIZED by excessive sweating, can be generalized or focal. Generalized hyperhidrosis involves the entire body and is usually part of an underlying condition, most often an infectious, endocrine or neurologic disorder. Focal hyperhidrosis is idiopathic, occurring in otherwise healthy people. It affects 1 or more body areas, most often the palms, armpits, soles or face. Almost 3% of the general population, largely people aged between 25 and 64 years, experience hyperhidrosis. The condition carries a substantial psychological and social burden, since it interferes with daily activities. However, patients rarely seek a physician's help because many are unaware that they have a treatable medical disorder. Early detection and management of hyperhidrosis can significantly improve a patient's quality of life. There are various topical, systemic, surgical and nonsurgical treatments available with efficacy rates greater than 90%–95%.

Hyperhidrosis, or increased production of sweat, can have a deeply detrimental effect on a patient's quality of life, resulting in dramatic impairments of daily activities, social interactions and occupational activities.1,2 It can be generalized, involving the whole body, or focal, involving a limited body area, most often the feet, armpits, hands or face. It is as common a disorder as psoriasis.3 However, patients rarely seek a physician's help because many are unaware that they have a treatable medical disorder. In this article, we review the possible causes, pathophysiology, diagnosis and clinical manifestations of focal hyperhidrosis as well as the wide range of treatment modalities available today.

Epidemiology

A recent large epidemiological survey of 150 000 households in the United States has revealed that focal hyperhidrosis is present in 2.8% of the general population.4 The condition affects both men and women equally, and its prevalence was found to be the highest among people aged 25–64 years. The average age of onset is 25 years but depends primarily on the body area affected. Palmar and axillary hyperhidrosis have the earliest average onset, at 13 and 19 years respectively.4 As many as 82% of patients with palmar hyperhidrosis have reported onset in childhood.5 Focal hyperhidrosis appears to have an onset in childhood; however, people may not seek medical help until early adulthood. Armpits are affected in 51% of patients, feet in 29%, palms in 25% and the face in 20%.4,6 No studies have documented the natural course of the disease with increasing age, but in our experience, the severity of sweating seems to decrease in patients older than 50 years.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of focal hyperhidrosis is poorly understood. Sweat is produced by the body's sweat glands: there are up to 4 million sweat glands, of which about 3 million are eccrine sweat glands and the remainder are apocrine glands.7 Eccrine sweat glands are innervated by cholinergic fibres from the sympathetic nervous system. Their primary function is the secretion of sweat — an odourless, clear fluid that regulates body temperature — the rate of which is affected by emotional and gustatory stimuli. Eccrine sweat glands, which are responsible for focal hyperhidrosis, are distributed over nearly the entire body surface, although their density is highest in the soles of the feet and the forehead, followed by the palms and cheeks. Apocrine sweat glands are scent glands and are primarily confined to the axillary and urogenital regions. They are not involved in focal hyperhidrosis, and their function is regulated by hormonal processes. There are also mixed sweat glands called apoeccrine glands, which are primarily found in axillary and perianal areas. Their role in the pathophysiology of focal hyperhidrosis is unknown, although in some patients they constitute up to 45% of the sweat glands found in the axillary region.8

No histopathological changes in the sweat glands have been observed in patients with focal hyperhidrosis, nor do these patients have increased numbers of or larger sweat glands.7Rather, focal hyperhidrosis may represent a complex dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system, involving both the sympathetic and parasympathetic pathways. A genetic predisposition may exist, since 30%–50% of patients have a family history of hyperhidrosis.9 In a study by Shih and colleagues,10 patients with palmoplantar hyperhidrosis showed less reflex bradycardia in response to Valsalva's manoeuvre and a higher degree of vasoconstriction in response to finger immersion in cold water. Such an increased sympathetic activity through the T2–T3 ganglia could cause palmar hyperhidrosis. Excessive palmar and plantar sweating could thus result in a vicious cycle, as evaporative cooling of the skin increases sympathetic outflow through reflex action, which in turn increases sweat output. Parasympathetic dysfunction was implicated in a study that compared heart rate variability in patients with focal hyperhidrosis with that of healthy control subjects.11 The authors found that, although sympathetic activity seemed to be similar, patients with focal hyperhidrosis exhibited heart rate patterns suggesting parasympathetic dysfunction.

Diagnosis and clinical presentation

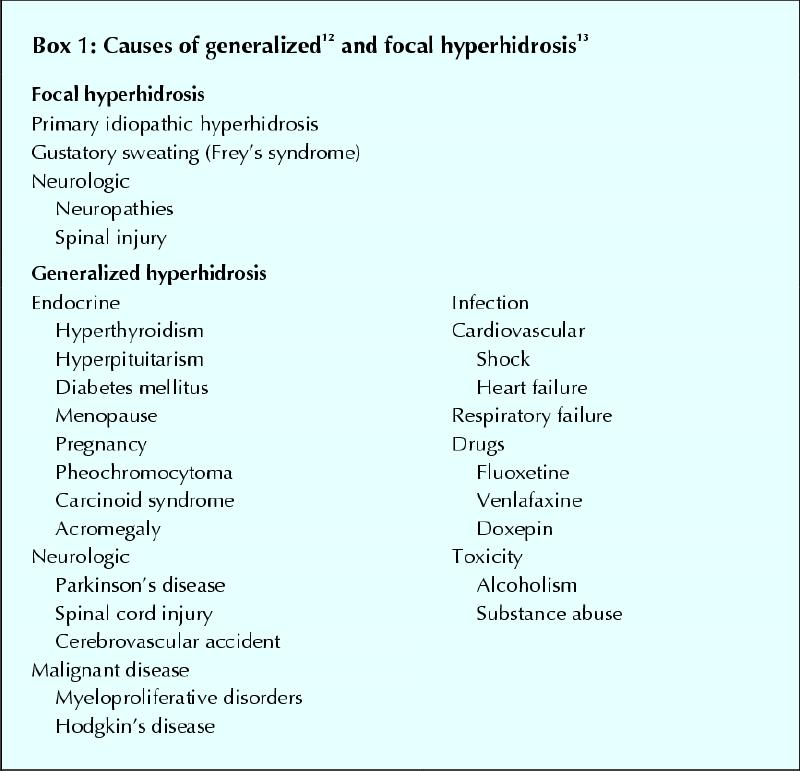

The first step in the evaluation of hyperhidrosis is to differentiate between generalized and focal hyperhidrosis. Generalized hyperhidrosis is usually part of some other underlying condition, such as infective or malignant disease or a hormonal disorder,12 and focal or primary idiopathic hyperhidrosis occurs in otherwise healthy people (Box 1). It usually peaks in the second or third decade of life and manifests as bilateral excessive sweat production confined to the armpits, soles of the feet, palms of the hands, face or other specific sites. Gustatory sweating (Frey's syndrome) is also a form of focal hyperhidrosis. A positive family history is evident in 30%–50% of patients.9Furthermore, patients with focal hyperhidrosis generally do not sweat during sleep. Thus, a medical history focusing on location of excessive sweating, duration of the presentation, family history, age at onset and the absence of any apparent cause allows one to easily differentiate focal from generalized hyperhidrosis (Box 2). Although there is no standard definition of focal hyperhidrosis, less than 1 mL/m2 of sweat production per minute by eccrine glands at rest and at room temperature is considered normal.8Alternatively, sweat rates of discrete anatomic areas (e.g., palm, axilla) may be measured for research purposes (e.g., normal sweat rates for the axilla are < 20 mg/min).13 For practical clinical purposes, any degree of sweating that interferes with the activities of daily living should be viewed as abnormal.

Box 1.

Box 2.

Diagnosis of focal hyperhidrosis does not require laboratory investigations. A starch iodine test can be used to outline the area of excessive sweating (Fig. 1). Iodine solution (1%–5%) is applied to a dry surface, and after a few seconds starch is sprinkled over this area. The starch and iodine interact in the presence of sweat, leaving a purplish sediment. This purple area identifies the duct of the sweat gland. Although the starch iodine test is not necessary for diagnosis, it allows the qualitative identification of areas of excessive sweating, which can be recorded by pictures taken before and after treatment.

Fig. 1: A starch iodine test is used to outline the area of excessive sweating. Iodine solution (1%–5%) is applied to a dry surface, followed by a sprinkling of starch (top). The iodine and starch interact in the presence of sweat, leaving a purplish sediment (bottom).

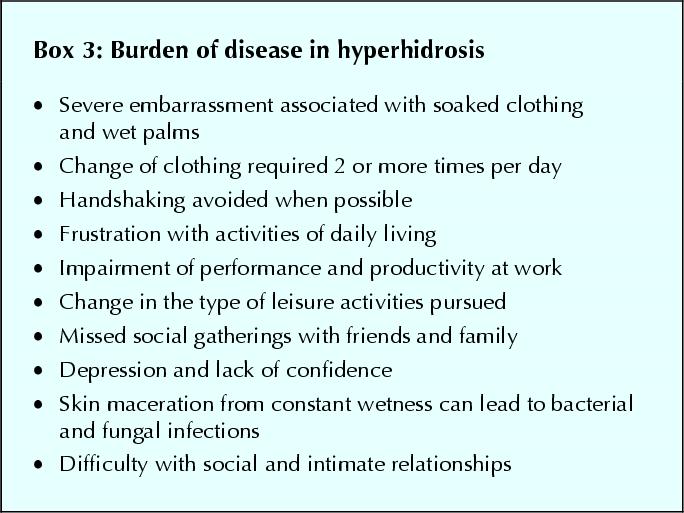

Psychosocial impairment is a significant aspect of focal hyperhidrosis (Box 3). In a US survey, one-third of patients with axillary hyperhidrosis reported their sweating as being barely tolerable or intolerable and as frequently interfering with activities of daily living; 35% of patients reported a decrease in leisure activity time due to excessive sweating.4 Many patients with focal hyperhidrosis go to considerable lengths to hide their condition,1 and social interactions are significantly impaired, since patients experience feelings of humiliation and embarrassment. Simple aspects of socialization, such as shaking hands or hugging, become awkward. Focal hyperhidrosis also has a profound impact on occupational activities. Despite this, only one-third of the survey participants had consulted a physician about their problem. Clearly, primary care physicians can be instrumental in the initial diagnosis and assessment of this condition.

Box 3.

Treatment

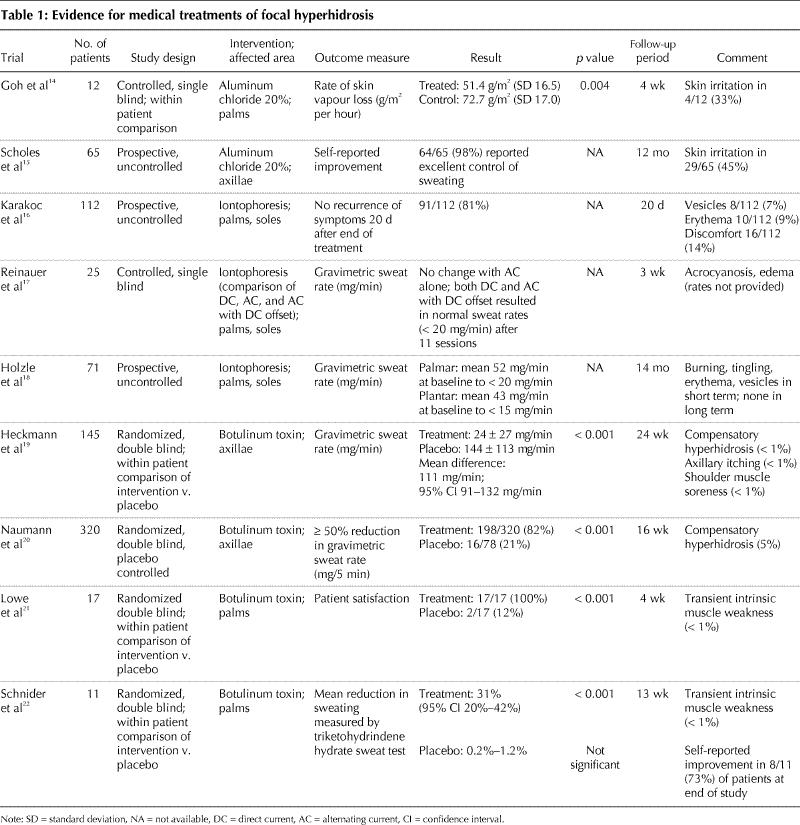

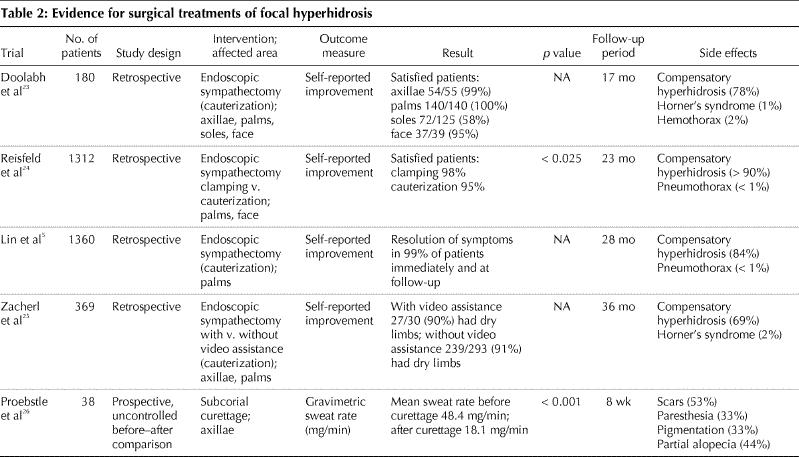

There is a wide range of nonsurgical (e.g., topical, systemic) and surgical treatments available for patients with focal hyperhidrosis. These treatment modalities vary in their therapeutic efficacy, duration of effect, side effects and cost, as well as in the scientific evidence of their efficacy (Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 1

Table 2

Topical treatments

Aluminum salts are the most common ingredient in over-the-counter antiperspirants used to treat focal hyperhidrosis. It has been postulated that the mechanism of their action is related to mechanical obstruction of the eccrine gland duct or to atrophy of the secretory cells.27 The concentrations of aluminum salts in most commercial antiperspirants is 1%–2%; however, aluminum chloride solutions are available in 20%–25% concentrations. Repeated applications are often necessary every 24–48 hours. Improvement can be seen in mild cases within 3 weeks of treatment. The major limitation of aluminum chloride products is localized burning, stinging and irritation. To minimize irritation, these products can be applied to the affected area at bedtime and washed off after 6–8 hours. According to the literature, 25% aluminum chloride is an effective first-line treatment for mild axillary hyperhidrosis.28 Aluminum chloride 20% can reduce palmar hyperhidrosis within 48 hours after application, but the effect diminishes within 48 hours after the end of treatment.14 Aluminum chloride 20% in alcohol can be effective in as many as 98% of cases of mild axillary hyperhidrosis.15

Topical aldehyde agents, such as formaldehyde and glutaraldehyde, have limited use in the treatment of focal hyperhidrosis because they can cause allergic sensitization and localized skin irritation.29

Iontophoresis

Iontophoresis is defined as the introduction of ions into the skin by means of an electrical current. The mode of action is not yet clear, but it is postulated that a charged particle obstructs the duct or the electrical change disrupts eccrine gland secretion.30 The procedure entails placing the hands or feet in a shallow basin filled with water, through which an electric current is passed. Iontophoresis is primarily used for focal palmoplantar hyperhidrosis, since the hands and feet are the easiest body parts to submerge in water.

Iontophoresis has not been studied in large randomized controlled trials, but it has been reported to be 80%– 100% effective in uncontrolled trials.16,17,18,31 However, long-term maintenance therapy is generally required. The limitation of this treatment is that it causes skin irritation, dryness and peeling. It is also time consuming, as it may require 30–40 minutes per treatment site daily for at least 4 days a week. Normal sweating is generally achieved after 6–10 treatments. Overall, iontophoresis is considered a second-line treatment for focal palmoplantar hyperhidrosis and is contraindicated in patients who are pregnant or who have a pacemaker.

Botulinum toxin A

Botulinum toxin A is the best-studied treatment to date for focal hyperhidrosis. It is a neurotoxin produced by the anaerobic bacterium Clostridium botulinum;32 7 serotypes of toxin exist, of which type A is the most potent. When used to treat focal hyperhidrosis, botulinum toxin is injected intradermally and acts to inhibit the release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction and from sympathetic nerves that innervate eccrine sweat glands, which results in loss of sweating (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3).34

Fig. 2: Intradermal botulinum toxin injections for the treatment of axillary hyperhidrosis. Focal axillary hyperhidrosis is treated with 50–200 units of botulinum toxin A per axilla. The usual starting dose is 50 units per axilla. The drug is injected intradermally using a 13-mm-long 30-gauge needle. Injections are done in a grid-like pattern in order to cover the entire affected area, with injection sites generally 1–2 cm apart. There is no difference in efficacy of botulinum toxin A in the treatment of axillary hyperhidrosis when administered by subcutaneous or intradermal injection, but intradermal injections are reported to be more painful.33The subcutaneous injection technique requires further study for validation of the results.

Fig. 3: Intradermal botulinum toxin injections for the treatment of palmar hyperhidrosis. For palmar hyperhidrosis, intradermal injections spaced about 1–2 cm apart seem to give the best results. About 2 units of botulinum toxin A are injected per site as required, with a total dose of 100 units for each palm. The main limitation is that most patients find the injections painful and may require regional anesthesia via median, ulnar and radial nerve blocks at the wrist level. A similar technique and dosage of botulinum toxin A is used for the treatment of plantar hyperhidrosis, requiring regional nerve blocks of posterior tibial and sural nerves for anesthesia. Other methods of reducing the pain of injections have included high-intensity vibration devices, cool packs and liquid nitrogen spray, all with variable results.13

Botulinum toxin has been evaluated as a treatment for axillary hyperhidrosis in 2 large randomized controlled trials.19,20 A significant improvement was reached in 95% of patients at 1 week, and the average duration of effect was 7 months. For palmar hyperhidrosis, the response rate was greater than 90%;21,22 the duration of effect was generally 4–6 months. The major limitation of this treatment is that the injections are painful and require a nerve block for anesthesia. However, patient satisfaction in randomized controlled trials with botulinum toxin was nearly 100%. Excellent response rates to botulinum toxin injection in plantar hyperhidrosis have also been reported35,36,37 but still need to be confirmed by controlled studies.

Contraindications to botulinum toxin therapy include neuromuscular disorders such as myasthenia gravis, pregnancy and lactation, organic causes of hyperhidrosis, and medications that may interfere with neuromuscular transmission. For this treatment, patients should be referred to physicians specialized in the administration of botulinum toxin. It must be noted, however, that the cost of the drug is a limitation to its wider use.

Surgical treatments

Surgical treatments include endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy, which destroys the sympathetic ganglia by excision, clamping, transection or ablation with cautery or laser. Several retrospective studies and uncontrolled clinical trials have demonstrated that endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy is effective in eliminating axillary, palmar and facial hyperhidrosis in 68%–100% of cases.5,23,24,25 Plantar hyperhidrosis was reduced in 58%–85% of patients. The main limitation of this procedure is a high incidence of mild to severe compensatory hyperhidrosis, usually involving the trunk and lower limbs, in up to 86% of patients.34 Other adverse effects include gustatory sweating, phantom sweating (the sensation of impending hyperhidrosis in the absence of sweating), neuralgia, Horner's syndrome and the risk of hemothorax or pneumothorax.34 Furthermore, lumbar sympathectomy for plantar hyperhidrosis is associated with sexual dysfunction.13 Other surgical procedures with reported efficacy include excision of axillary tissue and subcutaneous axillary curettage and liposuction.26,38,39 Surgical options for focal hyperhidrosis are associated with high efficacy rates, but they should be reserved for patients for whom other treatments have been ineffective and who appreciate the risks associated with the procedure and potential complications.

Systemic treatments

The main systemic agents used to treat focal hyperhidrosis are anticholinergic agents. By inhibiting synaptic acetylcholine, they interfere with neuroglandular signalling.34The main limitation of these drugs is that the doses required to achieve reduced sweating may also result in adverse effects such as dry mouth, blurred vision, urinary retention, constipation and tachycardia. Glycopyrrolate, an anticholinergic drug, at initial doses of 1 mg twice daily may improve hyperhidrosis, but the eventual dosage required usually results in unacceptable side effects.34 Other systemic agents include amitriptyline, clonazepam, β-blockers (e.g., propranolol) and calcium-channel blockers (e.g., diltiazem), gabapentin and indomethacin.34,40,41,42 However, these drugs have been used mostly by patients with generalized hyperhidrosis; their role in the treatment of focal hyperhidrosis remains to be established.

Alternative treatments

Biofeedback training, hypnosis and different types of relaxation techniques have been used to treat hyperhidrosis,43,44 but research data on their efficacy are still scarce to nonexistent. The lack of well- designed trials and long-term follow-up limits their use.

Conclusion

Various treatments of focal hyperhidrosis are available. Aluminum chloride-based topical treatments can be used as first-line treatment of axillary hyperhidrosis, which is the most frequent form of focal hyperhidrosis, as well as of palmar hyperhidrosis. Iontophoresis can be used as second-line treatment of palmar and plantar hyperhidrosis. Botulinum toxin seems the most effective treatment, but it is painful and costly. Surgical thoracic sympathectomy may be the only solution for patients with severe hyperhidrosis in whom other treatments have not produced satisfactory results. The role of alternative and systemic treatments in focal hyperhidrosis remains to be established. Given that effective treatment can result in dramatic improvements to a patient's quality of life, physicians can play an instrumental role in the diagnosis and management of this distressing condition.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Both authors drafted and revised the ariticle and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Nowell Solish, Rm. 841, 76 Grenville St., Sunnybrook and Women's College Health Sciences Centre, Toronto ON M5S 1B2

References

- 1.Amir M, Arish A, Weinstein Y, Pfeffer M, Levy Y. Impairment in quality of life among patients seeking surgery for hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating): preliminary results. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 2000;37(1):25-31. [PubMed]

- 2.Lerer B, Jacobowitz J, Wahaba A. Personality features in essential hyperhidrosis. Int J Psychiatry Med 1981;10:59-67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Christophers E, Kruger G. Psoriasis. In: Fitzpatrick TB, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, editors. Dermatology in general medicine. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1987. p. 465.

- 4.Strutton DR, Kowalski JW, Glaser DA, Stang PE. US prevalence of hyperhidrosisand impact on individuals with axillary hyperhidrosis: Results from a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;51(2):241-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Lin TS, Fang HY. Transthoracic endoscopic sympathectomy in the treatment of palmar hyperhidrosis — with emphasis on perioperative management (1360 case analysis). Surg Neurol 1999;52:453-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kinkelin I, Hund M, Naumann M, Hamm H. Effective treatment of frontal hyperhidrosis with botulinum toxin A. Br J Dermatol 2000;143(4):824-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Sato K, Kang WH, Saga K, Sato KT. Biology of sweat glands and their disorders II. Disorders of sweat gland function. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989;20(5 Pt 1):713-26. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Sato K, Kang WH, Saga KT. Biology of sweat glands and their disorders I. Normal sweat gland function. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989;20(4):537-63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Stolman LP. Treatment of hyperhidrosis. Dermatol Clin 1998;16:863-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Shih CJ, Wu JJ, Lin MT. Autonomic dysfunction in palmar hyperhidrosis. J Auton Nerv Syst 1983;8:33-43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Birner P, Heinzl H, Schindl M, Pumprla J, Schnider P. Cardiac autonomic function in patients suffering from primary focal hyperhidrosis. Eur Neurol 2000;44(2):112-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Boni R. Generalized hyperhidrosis and its systemic treatment. Curr Probl Dermatol 2002;30:44-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Hornberger J, Grimes K, Naumann M, Glaser DA, Lowe NJ, Naver H, et al; Multi-Specialty Working Group on the Recognition, Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Focal Hyperhidrosis. Recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of primary focal hyperhidrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;51:274-86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Goh CL. Aluminum chloride hexahydrate versus palmar hyperhidrosis, evaporimeter assessment. Int J Dermatol 1990;29:368-70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Scholes KT, Crow KD, Ellis JP, Harman RR, Saihan EM. Axillary hyperhidrosis treated with alcoholic solution of aluminum chloride hexahydrate. BMJ 1978;2:84-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Karakoc Y, Aydemir EH, Kalkan MT, Unal G, et al. Safe control of palmoplantar hyperhidrosis with direct electrical current. Int J Dermatol 2002; 41 (9): 602 -5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Reinauer S, Neusser A, Schauf G, Holzle E. Iontophoresis with alternating current and direct current offset (AC/DC iontophoresis): a new approach for the treatment of hyperhidrosis. Br J Dermatol 1993;129(2):166-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Holzle E, Alberti N. Long term efficacy and side effects of tap water iontophoresis of palmoplantar hyperhidrosis — the usefulness of home therapy. Dermatologica 1987;175:126-35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Heckmann M, Ceballos-Baumann AO, Plewig G. Botulinum toxin A for axillary hyperhidrosis. N Engl J Med 2001;344:488-93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Naumann M, Lowe NJ. Botulinum toxin type A in treatment of bilateral primary axillary hyperhidrosis: a randomised, parallel group, double blind, placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2001;323:596-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Lowe NJ, Yamauchi PS, Lask GP, Patnaik R, Iyer S. Efficacy and safety of botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of palmar hyperhidrosis: A double blind randomized placebo controlled study. Dermatol Surg 2002;28(9):822-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Schnider P, Binder M, Auff E, Kittler H, Berger T, Wolff K. Double blind trial of botulinum A toxin for the treatment of focal hyperhidrosis of the palms. Br J Dermatol 1997;136(4):548-52. [PubMed]

- 23.Doolabh N, Horswell S, Williams M, Huber L, Prince S, Meyer DM, et al. Thoracoscopic sympathectomy for hyperhidrosis: indications and results. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;77(2):410-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Reisfeld R, Nguyen R, Pnini A. Endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy for hyperhidrosis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutane Tech 2002;12(4):255-67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Zacherl J, Imhof M, Huber ER, Plas EG, Herbst F, Jakesz R, Video assistance reduces complication rate of thoracoscopic sympathectomy for hyperhidrosis. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;68(4):1177-81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Proebstle TM, Schneiders V, Knop J. Gravimetrically controlled efficacy of subcorial curettage: a prospective study for treatment of axillary hyperhidrosis. Dermatol Surg 2002;28(11):1022-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Holzle E, Kligman AM. Mechanism of antiperspirant action of aluminum salts. J Soc Cosm Chem 1979;30:279-95.

- 28.Shelly WB, Hurley HJ. Studies on topical antiperspirant control of axillary hyperhidrosis. Acta Derm Venereol (stockh) 1975;55:241-60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.White JW. Treatment of primary hyperhidrosis. Mayo Clin Proc 1986;61:951-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Sato K, Timm DE, Sato F, Templeton EA, Meletiou DS, Toyomoto T, et al. Generation and transit pathway of H+ is critical for inhibition of palmar sweating by iontophoresis in water. J Appl Physiol 1993;75(5):2258-64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Bouman H. The treatment of hyperhidrosis of hands and feet with constant current. Am J Phys Med 1952;31:158-69. [PubMed]

- 32.Simpson LL. Molecular pharmacology of botulinum toxin and tetanus toxin. Ann Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 1986;26:427-53. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Pearson C, Cliff S. Botulinum toxin type A treatment for axillary hyperhidrosis: a comparison of intradermal and subcutaneous injection techniques. Br J Dermatol 2004;151(suppl 68):95.

- 34.Connolly M, de Berker D. Management of primary hyperhidrosis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003;4(10):681-97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Naumann M. Focal hyperhidrosis: effective treatment with intracutaneous botulinum toxin. Arch Dermatol 1998;134(3):301-4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Sevim S, Dogu O, Kaleagasi H. Botulinum toxin A therapy for palmar and plantar hyperhidrosis. Acta Neurol Belg 2002;102(4):167-70. [PubMed]

- 37.Vodoud-Seyedi J, Simonart T, Heen T. Treatment of plantar hyperhidrosis with dermojet injections of botulinum toxin. Dermatology 2000;201(2):179. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Jemec B. Abrasio axillae in hyperhidrosis. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg 1975; 9: 44- 6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Lillis PJ, Coleman WP. Liposuction for the treatment of axillary hyperhidrosis. Dermatol Clin 1990;8:479-82. [PubMed]

- 40.Eedy DJ, Corbett JR. Olfactory facial hyperhidrosis responding to amitriptyline. Clin Exp Dermtol 1978;12:298-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Tkach JR. Indomethacin treatment of generalized hyperhidrosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1982;6:545. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Feder R. Clonidine treatment of excessive sweating. J Clin Psychiatry 1995; 56: 35. [PubMed]

- 43.Duller P, Gentry WD. Use of biofeedback in treating chronic hyperhidrosis: a preliminary report. Br J Dermatol 1980;103:143-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Shenefelt PD. Hypnosis in dermatology. Arch Dermatol 2000;136:393-9. [DOI] [PubMed]