Abstract

Background

Maximum aerobic capacity (VO2max) is associated with lower cardiovascular and total mortality. Step tests can be used to provide an estimate of (VO2max) in epidemiological or home-based studies. We compared different methods of estimation of VO2max and heart rate recovery and evaluated the relationship of these estimates with cardiovascular risk factors.

Methods

Data were analysed from 2286 participants in the Tecumseh Community Health Study (>16 y and <70 y) who performed a step test. VO2max was estimated from heart rate using three methods and the results compared. The magnitude of heart rate recovery (HRR) and the time constant of recovery based on different time intervals post-exercise were also estimated.

Results

Estimated VO2max showed good or poor agreement depending on the method used. VO2max correlated inversely with systolic blood pressure (SBP), body mass index (BMI), total cholesterol, blood glucose following a 100 g oral load (PLG) and Framingham risk score. In a multivariable model age sex, cigarette smoking, SBP, BMI and PLG were significantly inversely associated with VO2max. Correlations with risk factors were strongest for HRR measured over the first 30 s of recovery. Only the time constant calculated from the 3 min post-exercise period correlated significantly with risk factors.

Conclusions

The Tecumseh step test can be used to provide estimates of VO2max and heart rate recovery. Estimated VO2max was inversely associated with higher systolic BP, higher BMI and worse glucose tolerance. Measurements of HRR over the first 30 s and the time constant calculate from the first 3 min of recovery correlate most closely with risk factors.

Keywords: Exercise, Cardiovascular risk, Oxygen consumption, Step test, Heart rate

Highlights

-

•

Estimates of aerobic capacity (VO2max) and heart rate recovery using a step test were compared.

-

•

Associations between VO2max and cardiovascular risk factors were examined.

-

•

Estimated VO2max showed good or poor agreement depending on the method used.

-

•

VO2max correlated inversely with cardiovascular risk factors.

Introduction

A higher level of cardiorespiratory fitness, assessed as maximum aerobic capacity (VO2max), is associated with lower cardiovascular and total mortality.1 However direct measurement of peak oxygen consumption by incremental exercise is time consuming, requires appropriate expertise, and is not entirely without risk.2 Step testing combined with measurement of heart rate is a convenient, safe and inexpensive submaximal test from which VO2max can be estimated with acceptable accuracy3, 4, 5, 6 and precision.7, 8 Step tests are particularly appropriate for epidemiological work or studies in the home since steps are easily transportable and stepping technique requires little practice.9

However, previously validated equations are test specific, with uncertain transferability to other step tests. Further, most currently validated tests have limitations which reduce applicability. For example, the height of the step employed by McArdle et al.8 is 40 cm, while the Canadian Home Fitness Step Test is an incremental test with two 20 cm steps. These can be challenging tests for an older population, resulting in poor compliance, and multiple steps are cumbersome for home visits. The Tecumseh step test offers advantages in that it is a 3 min step test which employs a single step with a comparatively low height (20 cm) to ensure that measurement of aerobic capacity is not limited by local muscle fatigue.10, 11 It has been used successfully in children and adults10, 11; however, information regarding estimation of VO2max using this test is limited12 and the relationship of VO2max estimated by this test to cardiovascular risk factors has not been described. In addition, the rate and extent of heart rate recovery following exercise has been proposed as an indicator of autonomic function13 and physical fitness14 and has also been reported to predict future cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality.15

The aim of this study was to compare available equations estimating VO2max in the Tecumseh study against a validated equation, to determine heart rate recovery, to evaluate the relationship of these estimates with cardiovascular (CVD) risk factors, and to assess the feasibility of estimation of VO2max and measures of heart rate recovery based only on 2 post-exercise measurements of heart rate (30 s and 3 min post-exercise).

Methods

Sample

The Tecumseh Community Health Study was a longitudinal study of individuals living in Tecumseh, Michigan which commenced in 1957 when all 8800 residents of the 2400 households in Tecumseh were canvassed. Data used in this study were collected over the years 1959–1969 (Round I: 1959–1960, Round II: 1962–1965, and Round III: 1967–1969) and the study achieved a ∼88% response rate.16 In each of three rounds of data collection interviews and medical examinations were conducted with remaining and new household residents, yielding a total of 11,563 persons who were examined at least once and 4312 who were examined during all three rounds.17 The current work is based on publically available data for those who undertook step tests in Round II.

Step test

For the purpose of this analysis, data were restricted to individuals >16 y and less than 70 y (n = 2286; Table 1). Exclusion criteria for the step test were: known heart disease or stroke, acute severe respiratory infections, severe arthritis or other orthopaedic disabilities, severe hypertension (>170 systolic and/or >110 diastolic) and pregnancy.10, 11 Approximately 84% of study participants in Round II undertook the step test. The step test was administered in an air-conditioned room (22–24 °C) and consisted of stepping onto an 20 cm (8 inch) bench for 3 min at a rate of 24 steps per min using a metronome. This corresponds to ∼5 times the rate of resting energy metabolism (∼5METS). Heart rates were measured by ECG while the subject was sitting and standing before exercise, during exercise, and at 0.5 1, 2, 3 and 5 min after exercise while the subject was sitting.

Table 1.

Sample demographics and average results.

| Variable | N | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 2286 | 35.7 | 12.0 |

| Male, N (%) | 1086 | 48% | |

| Height, cm | 2268 | 168.0 | 9.0 |

| Weight, kg | 2349 | 69.2 | 13.4 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 2205 | 24.6 | 3.6 |

| Post-load glucose, mg/dl | 2136 | 132.2 | 39.6 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 2189 | 129.9 | 15.4 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 2101 | 85.1 | 10.6 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 2235 | 214.1 | 44.4 |

| Cigarette smoker, non/current/ex | 944/1080/246 | 42%/48%/11% | |

| VO2max(M) | 2286 | 2.33 | 0.66 |

| VO2max(S) | 2286 | 2.79 | 0.65 |

| VO2max(AVD) | 2237 | 2.35 | 0.48 |

| HRR30, bpm | 2230 | 25.3 | 9.2 |

| HRR1, bpm | 1600 | 36.6 | 11.2 |

| HRR2, bpm | 1609 | 41.7 | 11.8 |

| HRR3, bpm | 1604 | 42.7 | 11.3 |

| HRRh3, bpm | 1621 | 17.8 | 8.3 |

| tc0–3, s | 1564 | 53.7 | 1.6 |

| tch3, s | 1621 | 53.5 | 2.6 |

Abbreviations: HRR30, heart rate recovery at 30 s; HRR1, heart rate recovery at 1 min; HRR2, heart rate recovery at 2 min; HRR3, heart rate recovery at 3 min; HRRh3, heart rate recovery between 30 s and 3 min; SD, standard deviation; tc0–3, time constant of heart rate recovery over 0–3 min post exercise; tch3, time constant of heart rate recovery estimated from heart rate at 30 s and 3 min; VO2max(M), estimated maximal oxygen consumption using Milligan equation; VO2max(S), estimated maximal oxygen consumption using Sharkey equation; VO2max(AVD), estimated maximal oxygen consumption using Astrand/Van Dobeln equations. Missing variables account for the different N's. Post-load glucose values were restricted to those receiving 100 g glucose.

Other measurements

Participants completed a questionnaire and measurements of height, weight, blood pressure, and blood glucose following a 100 g load (post load glucose (PLG)) and total cholesterol (TC) was performed as previously described.10, 11, 18 Sitting blood pressure was measured in the right arm by a trained technician using a sphygmomanometer.

Calculation of VO2max using submaximal exercise data

An equation relating heart rate following the Tecumseh step test to directly measured peak oxygen consumption (ml/min/kg) based on 100 individuals (52 males, age 18–58 y) was recently reported by Milligan (VO2max(M))12:

| (1) |

where HRpost is heart rate 30 s following exercise.

Estimates from this validated equation were compared with peak oxygen consumption (ml/min/kg) estimated by the Astrand/Van Dobeln (AVD) equations:

| (2) |

| (3) |

where exercise heart rate was the average of the heart rate at 2 min 30 s and 3 min after initiation of exercise. The paper by Van Dobeln et al.6 only gives parameters for men, so the parameters for women were derived from the data for women given by Astrand.5

A further comparison was made with estimates calculated using the equation by Sharkey cited in Refs. 3, 4 which estimates peak oxygen consumption (l/min) as:

| (4) |

| (5) |

where

| (6) |

| (7) |

For the purposes of this comparison VO2max(M) calculated by the Milligan equation was multiplied by weight[kg]/1000 to estimate peak oxygen consumption in l/min.

Heart rate recovery

HRR13 was calculated as the difference between heart rate at the end of exercise and post-exercise recovery heart rate at 30 s (HRR30), 1 min (HRR1), 2 min (HRR2) and 3 min (HRR3). The difference between heart rate at 30 s after exercise and 3 min following the end of exercise (HRRh3) was also calculated. The time constants of the rate of decline in heart rate following cessation of exercise was also calculated by fitting an exponential function of the form

where HR(t) is heart rate at time, t, k is the rate constant and a and c are constants. The time constant was estimated as 1/k. Time constants were estimated from data collected over the period 0 (end-exercise) to 3 min (t0–3) and using heart rate measured at 30 s and 3 min (th3).

Statistics

All statistical analysis was conducted using Stata SE 14.2. Continuous data were summarized as mean (SD) of N observations, categorical data as N (%). Method comparison was performed using Bland Altman analysis; mean difference and limits of agreement (d[LOA]) in addition to Lin's concordance coefficient, ρ (asymptotic 95% confidence interval) were used as summary measures of agreement. Correlation and multiple linear regression was performed to examine bivariate correlations between VO2max(M) or measures of heart rate recovery with cardiovascular risk factors (systolic blood pressure (SBP), BMI, PLG and TC). Further multivariable regression was also undertaken: in these models age, sex, education grade, alcohol intake and cigarette smoking were included (chosen a priori) as possible confounders. Framingham 10-year cardiovascular risk score (FRS) was calculated as previously described19 using Ariel Linden's Stata module Framingham (http://www.lindenconsulting.org/stats.html); however, since high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) was not measured in the Tecumseh study, HDL-C values for estimation of FRS were imputed based on age, sex and body mass index (BMI) using regression equations calculated from the Framingham Heart Study dataset. Statistical significance was assigned if P < 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the sample and results are shown in Table 1. Mean age of participants was 35.7 (range 16–69 y and 48% were men).

Estimates of VO2max

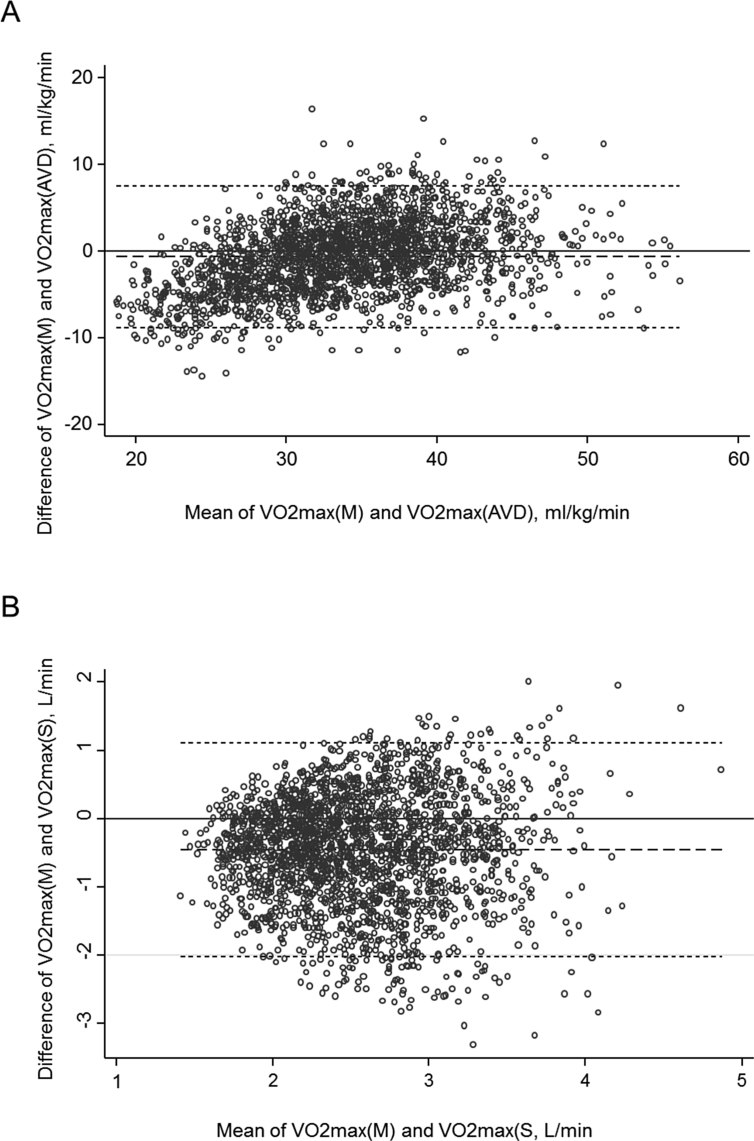

Bland Altman plots of the estimates of VO2max by the different methods are shown in Fig. 1A and B. VO2max(M) and VO2max(AVD) (d = −0.7 [−8.9, 7.5] ml/kg/min and ρ = 0.80 (079, 0.81)) showed good agreement with no evidence of bias. Agreement between VO2max(M) and VO2max(S) (d = −0.46 [−2.02, 1.10] l/min and ρ = 0.21 (0.17, 0.24)) was poor.

Figure 1.

Bland Altman plots for comparison of estimated maximum oxygen consumption using A) Milligan equation (VO2max(M)) vs. Astrand/Van Dobeln equations (VO2max(AVD)), B) Milligan equation (VO2max(M)) vs. Sharkey equation (VO2max(S)). Dashed line indicates the mean difference and the short dashed lines indicate the limits of agreement.

Correlations and multivariable associations between estimated VO2max and risk factors

Correlations between VO2max(M) and CVD risk factors, including FRS, are shown in Table 2, Table 3. VO2max(M) was significantly inversely correlated with each of the individual risk factors and showed a stronger inverse correlation with FRS. In a multivariable model including the same variables plus potential confounders (age sex, and cigarette smoking, education grade and alcohol intake) SBP, BMI and PLG were significantly inversely associated with VO2max(M) in addition to the anticipated inverse relationships with age, sex and current smoking.

Table 2.

Correlations between VO2max(M), ml/min/kg and systolic blood pressure, body mass index, post-load glucose, total cholesterol and Framingham coronary heart disease risk score.

| VO2max(M) | SBP | BMI | PLG | TC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP | −0.24 | ||||

| BMI | −0.24 | 0.36 | |||

| PLG | −0.27 | 0.18 | 0.13 | ||

| TC | −0.31 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.15 | |

| FRSa | −0.52 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.28 | 0.56 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; FRS, Framingham coronary heart disease risk score, PLG, post-load glucose; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; VO2max(M), estimated maximal oxygen consumption using Milligan equation. Data are Pearson's (or aSpearman's) correlation coefficients, values in bold indicate P < 0.001. All P values were calculated using a Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

Table 3.

A multivariate model of the association of maximum oxygen consumption (VO2max(M)) with risk factors.

| Beta coefficient | Adjusted R-squared = 0.42 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI | P value | |||

| Age, y | −0.4 | −0.4 | −0.3 | <0.001 |

| Female sex | −4.6 | −5.3 | −4.0 | <0.001 |

| Smoking | ||||

| Current | −1.7 | −2.4 | −1.0 | <0.001 |

| Ex | −0.5 | −1.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| Alcohol, Oz/week | −0.002 | −0.006 | 0.002 | 0.3 |

| Education grade | −0.1 | −0.3 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | −0.05 | −0.07 | −0.03 | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | −0.26 | −0.35 | −0.17 | <0.001 |

| Post-load glucose, mg/dl | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.01 | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | −0.004 | −0.011 | 0.003 | 0.3 |

| Constant | 66.5 | 63.1 | 69.8 | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Correlation and agreement between estimates of HRR and time constants of heart rate recovery

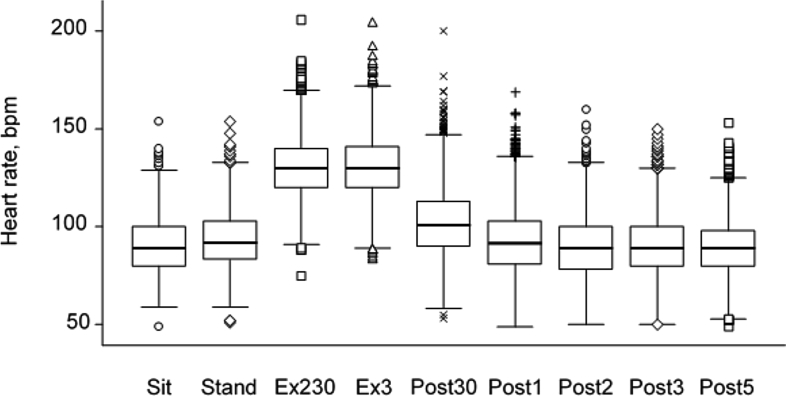

Heart rates at rest, standing, and throughout exercise and recovery are shown in Fig. 2. Heart rate recovered to resting levels by ∼2–3 min. HRR30, HRR1, HRR2 and HRR3 were strongly correlated, however there was an inverse correlation between HRR30 and HRRh3, a weak correlation between HRR1 and HRRh3, and between HRRh3 and HRR2, and a moderate correlation between HRRh3 and HRR3 (Table 4A). Agreement was good between t0–3 and th3 (d = 0.2 [−3.0, 3.4]; ρ = 0.72 (0.70, 0.74)) and both time constants were closely positively correlated to one another and inversely correlated with HRR1, HRR2, HRR3 and HRRh3 (Table 4A).

Figure 2.

Box plot of heart rate before, during and after exercise. Abbreviations: Sit, sitting; Stand, standing prior to exercise; Ex230, 2 min 30 s of exercise; Ex3, 3 min of exercise; Post30, 30 s post-exercise; Post1, 1 min post-exercise; Post2, 2 min post-exercise; Post3, 3 min post-exercise; Post5, 5 min post-exercise.

Table 4.

A) Correlations between measures of heart rate recovery. B) Correlations between measures of heart rate recovery and risk factors.

| HRR30 | HRR1 | HRR2 | HRR3 | HRRh3 | tc0–3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRR1 | 0.79 | |||||

| HRR2 | 0.71 | 0.82 | ||||

| HRR3 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.85 | |||

| HRRh3 | −0.17 | 0.19 | 0.38 | 0.59 | ||

| tc0–3 | −0.48 | −0.61 | −0.79 | −0.86 | −0.64 | |

| tch3 | 0.05 | −0.26 | −0.42 | −0.63 | −0.94 | 0.80 |

| HRR30 | HRR1 | HRR2 | HRR3 | HRRh3 | tc0–3 | tch3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP | −0.18 | −0.16 | −0.14 | −0.14 | 0.02 | 0.13 | 0.02 |

| BMI | −0.18 | −0.15 | −0.10 | −0.08 | 0.11 | 0.05 | −0.08 |

| PLG | −0.14 | −0.13 | −0.12 | −0.10a | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| TC | −0.20 | −0.16 | −0.14 | −0.10 | 0.07 | 0.06 | −0.06 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; HRR30, heart rate recovery at 30 s; HRR1, heart rate recovery at 1 min; HRR2, heart rate recovery at 2 min; HRR3, heart rate recovery at 3 min; HRRh3, heart rate recovery between 30 s and 3 min; PLG, post-load glucose; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; tc0–3, time constant of heart rate recovery over 0–3 min post exercise; tch3, time constant of heart rate recovery estimated from heart rate at 30 s and 3 min. Data are Pearson's correlation coefficients, values in bold indicate P < 0.001, except aP < 0.01. All P values were calculated using a Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

Correlation between measures of heart rate recovery and CVD risk factors

HRR30, HRR1, HRR2 and HRR3 correlated inversely with SBP, BMI, PLG and total cholesterol (Table 4B); correlations, although significant, were weak and tended to be stronger for HRR30 and progressively less strong for HRR1, HRR2 and HRR3. HRRh3 only correlated positively with BMI and not with other risk factors. t0–3 correlated positively, albeit weakly, with SBP and PLG whereas no significant correlations were observed between th3 and CVD risk factors. Multivariate modelling showed that negative associations between age and magnitude of heart rate recovery at various times and higher heart rate recovery in women were fairly consistent across the different measures. Negative associations between current smoking or BMI and HRR30 were progressively attenuated in measurements based on longer durations (HRR1, HRR2 and HRR3), while the association between BMI and HRRh3 reversed to become positive (Supplementary Tables S1–S5). Similarly, in multivariable models, shorter time constants of heart rate recovery in women were observed using both t0–3 and th3. However, associations between current smoking, SBP and PLG and slower time of recovery, which were evident using t0–3, were weaker and not significant for th3 (Supplementary Tables S6 and S7).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that estimates of VO2max derived from a Tecumseh step test, using a validated equation, agree closely with those estimated by the Astrand/Van Dobeln equations,5, 6 but considerably less well with estimates based on the equation formulated by Sharkey and used by Marley and Linnerud.3 The poorer agreement with this latter equation may result from its failure to account for age, since the relationship between heart rate and maximum oxygen consumption is known to decline with age.5, 6, 20 The equation described by Milligan12 has the advantage that it has been validated against maximal exercise determinations of aerobic capacity, however its limitation is that it assumes the decline in VO2max with age is similar in both sexes. There is evidence that this is not the case5, 6, 20 and this is incorporated into the Astrand/Van Dobeln equations. Nevertheless, the relatively close agreement between VO2max(M) and VO2max(AVD) suggests that both these equations probably provide acceptable estimates of VO2max within the recognized limits of estimation of aerobic capacity by submaximal exercise.21, 22

We further show that VO2max estimated by the validated Milligan equation is inversely correlated with systolic BP, BMI, higher glucose following a 100 g oral glucose load, serum cholesterol and FRS, a risk score that combines many of these individual risk factors and hence may account for risk factor clustering. In a multivariable model incorporating the individual risk factors, systolic BP, BMI, higher glucose following a 100 g oral glucose load were independently associated with VO2max. Similar associations were seen with VO2max estimated using the Astrand/Van Dobeln equations (data not shown). These findings are consistent with previous studies that used maximal exercise testing to determine VO2max,23, 24 and a study that used a submaximal step test, the Canadian Aerobic Fitness Test.25 In that study correlations between estimated VO2max and blood pressure, lipids, and BMI were of a similar magnitude to those reported here.

Estimates of HRR were reasonably correlated, except when it was calculated as the difference between heart rate at 30 s after exercise and 3 min following the end of exercise (HRRh3). This estimate only showed a moderate correlation with the other measures. The time constants of decline in heart rate after exercise correlated with one another more closely. The comparatively rapid decline in heart rate in the first minute of recovery is believed to be largely attributable to withdrawal of vagal tone, whereas the slower decline in heart rate over the subsequent 2–4 min is considered to reflect a combination of reduced vagal and sympathetic tone.13 Correlations between measures of heart rate recovery and CVD risk factors, although significant and in the anticipated direction were weak. Further, our data suggest that HRRh3 is not a useful measure of heart rate recovery. Similarly, although tc0–3 and tch3 correlate quite closely with one another, tch3 appears to be too imprecise a measure of the time course of heart rate recovery to be particularly useful in identifying weak associations with risk factors.

Although only resting blood pressure was measured in this study, a possible additional utility of this step test is that it can be used to determine the blood pressure response to sub-maximal exercise.26 Blood pressure measured after moderate exercise of similar intensity to that used here has been shown to be associated with target organ damage27 and to have prognostic significance independent of resting blood pressure.28

This study has strengths and weaknesses: it uses data from a large community-based sample of men and women, with minimal exclusions except for safety considerations, and covers a large age range enhancing its generalizability. However, the data were collected in the 1960s and there are no corresponding direct measurements of VO2max available, and measurements of CVD risk factors are limited. The sample was almost exclusively White Americans and our observations cannot necessarily be extrapolated to other ethnic groups. The data are cross-sectional and therefore should not be interpreted as demonstrating causal links between factors.

In summary, a Tecumseh step test can be used to provide valid estimates of VO2max using at least two equations, and can be used to measure heart rate recovery. Estimated VO2max was inversely associated with higher systolic BP, higher BMI and worse glucose tolerance. Measurement of heart rate recovery over the first 30 s and the time constant calculated over the entire first 3 min of recovery correlate most closely with CVD risk factors and are therefore the preferred outcome measure of this test.

Conflict of interest statement

No conflicts of interest.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgements

ADH and NC received support relevant to this work from a Biomedical Research Centre Award to University College London Hospital and the British Heart Foundation (PG/06/145, CS/13/1/30327 & CS/15/6/31468).

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.artres.2017.02.005.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Blair S.N., Kohl H.W., 3rd, Paffenbarger R.S., Jr., Clark D.G., Cooper K.H., Gibbons L.W. Physical fitness and all-cause mortality. A prospective study of healthy men and women. JAMA. 1989;262:2395–2401. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.17.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Sports Medicine, Thompson W.R., Gordon N.F., Pescatello L.S. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2009. ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marley W.P., Linnerud A.C. Astrand–Ryhming step test norms for college students. Br J Sports Med. 1976;10:76–79. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.10.2.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Druskins L.M., Smith J.L. The use of step tests for physical work capacity evaluation. In: Aghazadeh F., editor. Advances in industrial ergonomics and safety VI. Taylor & Francis; London, UK: 1994. pp. 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Astrand I. Aerobic work capacity in men and women with special reference to age. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1960;49:1–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Dobeln W., Astrand I., Bergstrom A. An analysis of age and other factors related to maximal oxygen uptake. J Appl Physiol. 1967;22:934–938. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1967.22.5.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckley J.P., Sim J., Eston R.G., Hession R., Fox R. Reliability and validity of measures taken during the Chester step test to predict aerobic power and to prescribe aerobic exercise. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38:197–205. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2003.005389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McArdle W.D., Katch F.I., Pechar G.S., Jacobson L., Ruck S. Reliability and interrelationships between maximal oxygen intake, physical work capacity and step-test scores in college women. Med Sci Sports. 1972;4:182–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siconolfi S.F., Garber C.E., Lasater T.M., Carleton R.A. A simple, valid step test for estimating maximal oxygen uptake in epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:382–390. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montoye H.J., Willis P.W., 3rd, Cunningham D.A., Keller J.B. Heart rate response to a modified Harvard step test: males and females, age 10–69. Res Q. 1969;40:153–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montoye H.J., Willis P.W., 3rd, Cunningham D.A. Heart rate response to submaximal exercise: relation to age and sex. J Gerontol. 1968;23:127–133. doi: 10.1093/geronj/23.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milligan G. University of Portsmouth; 2013. Fitness standards for the maritime and coastguard agency and the oil and gas industry. [PhD] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peçanha T., Bartels R., Brito L.C., Paula-Ribeiro M., Oliveira R.S., Goldberger J.J. Methods of assessment of the post-exercise cardiac autonomic recovery: a methodological review. Int J Cardiol. 2017;227:795–802. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darr K.C., Bassett D.R., Morgan B.J., Thomas D.P. Effects of age and training status on heart rate recovery after peak exercise. Am J Physiol. 1988;254:H340–H343. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1988.254.2.H340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cole C.R., Blackstone E.H., Pashkow F.J., Snader C.E., Lauer M.S. Heart-rate recovery immediately after exercise as a predictor of mortality. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1351–1357. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910283411804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Napier J.A., Johnson B.C., Epstein F.H. The Tecumseh, Michigan community health study. In: Kessler I.I., Levin M.L., editors. The community as an epidemiologic laboratory: a casebook of community studies. Johns Hopkins; Baltimore: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawthorne V. Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR); 1989. Tecumseh community health study, 1959–1969. [Distributor] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayner N.S., Kjelsberg M.O., Epstein F.H., Francis T., Jr. Carbohydrate tolerance and diabetes in a total community, Tecumseh, Michigan. 1. Effects of age, sex, and test conditions on one-hour glucose tolerance in adults. Diabetes. 1965;14:413–423. doi: 10.2337/diab.14.7.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D'Agostino R.B., Sr., Vasan R.S., Pencina M.J., Wolf P.A., Cobain M., Massaro J.M. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743–753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleg J.L., Morrell C.H., Bos A.G., Brant L.J., Talbot L.A., Wright J.G. Accelerated longitudinal decline of aerobic capacity in healthy older adults. Circulation. 2005;112:674–682. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.545459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies C.T. Limitations to the prediction of maximum oxygen intake from cardiac frequency measurements. J Appl Physiol. 1968;24:700–706. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1968.24.5.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Åstrand P.-O., Rodahl K. McGraw-Hill; New York, London: 1986. Textbook of work physiology: physiological bases of exercise. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carnethon M.R., Gulati M., Greenland P. Prevalence and cardiovascular disease correlates of low cardiorespiratory fitness in adolescents and adults. JAMA. 2005;294:2981–2988. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.23.2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper K.H., Pollock M.L., Martin R.P., White S.R., Linnerud A.C., Jackson A. Physical fitness levels vs selected coronary risk factors. A cross-sectional study. JAMA. 1976;236:166–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jette M., Sidney K., Quenneville J., Landry F. Relation between cardiorespiratory fitness and selected risk factors for coronary heart disease in a population of Canadian men and women. CMAJ. 1992;146:1353–1360. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chaturvedi N., Bathula R., Shore A.C., Panerai R., Potter J., Kooner J. South Asians have elevated postexercise blood pressure and myocardial oxygen consumption compared to Europeans despite equivalent resting pressure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1:e000281. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.111.000281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kokkinos P., Pittaras A., Narayan P., Faselis C., Singh S., Manolis A. Exercise capacity and blood pressure associations with left ventricular mass in prehypertensive individuals. Hypertension. 2007;49:55–61. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000250759.71323.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schultz M.G., Otahal P., Cleland V.J., Blizzard L., Marwick T.H., Sharman J.E. Exercise-induced hypertension, cardiovascular events, and mortality in patients undergoing exercise stress testing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens. 2013;26:357–366. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hps053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.