Abstract

Bullous lichen planus is a rare variant of lichen planus. It is characterized by vesicles or bullae, which usually develop in the context of pre-existing LP lesions. It is often misdiagnosed and should be differentiated from other subepidermal bullous diseases especially lichen planus pemphigoides. The diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion and is confirmed by histopathology and immunofluoresence. The clinical features of bullous lichen planus include typical lichen planus lesions, accompanied by the formation of bullae on the affected or perilesional skin. This is evident on histology, with alteration of the dermo-epidermal junction and intrabasal bullae as a consequence of extensive inflammation. The histologic features in conjunction with the negative immunofluoresence indicate that bullous lichen planus is a form of "hyper-reactive lichen planus" rather than a distinct entity. There is no standard treatment of bullous lichen planus. Topical and systemic corticosteroids, dapsone and acitretin have been described as effective choices.

Keywords: bullous lichen planus, lichen planus, lichen planus pemphigoides, review

Introduction

Lichen planus (LP) is a common, inflammatory disorder that affects the skin, nails, hair, and mucous membranes. It is the prototype of lichenoid eruptions, a term used to describe flat-topped papular LP-like eruptions or histopathologically liquefaction of basal cells and presence of band-like inflammatory cell infiltrate at the papillary dermis.[1]

The concomitant formation of blisters is rare and can be the effect of severe liquefactive degeneration of cells forming the basal layer (i.e. extensive inflammation). This form is called bullous lichen planus (BLP). In cases where the blisters form because of circulating autoantibodies the disease is called lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP).

BLP is an uncommon variant of LP, clinically characterized by vesicular and/or bullous lesions develop on pre-existing LP lesions or on perilesional skin. Literature is relatively poor regarding data about BLP.

Epidemiology

The exact prevalence of BLP remains unknown. The disease is usually sporadic. However, familial cases of BLP have also been described in literature.[2]

Familial BLP has an earlier onset and more prolonged course compared to non-familial BLP. It tends to affect the same areas as non-familial BLP, mainly lower and upper extremities, trunk and mucosa but it is more frequently associated with nail involvement.[3]

The role of hereditary factors in the development of BLP warrants further investigations and may reveal further aspects of its etiology.

Pathogenesis

BLP, as a subtype of LP is considered an immunologically mediated disorder. The initial trigger seems to be the expression of keratinocyte basal antigen.[4] Then, T-cells migrate to the epithelium either by random encounter of the keratinocyte basal antigen during routine surveillance or by a cytokine-mediated process. Accordingly, there is extensive lymphocytic infiltrate consisting mainly by CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells.[5] The activation of CD8+ cells plays a pivotal role to the disease process. This is achieved either directly by an antigen binding to the MHC class I on lesional keratinocytes or through activation from CD4+ cells.

Furthermore, in LP lesions there are increased numbers of CD4+ and Langerhans cells.[5,6] CD4+ cells are activated by antigens associated with MHC class II molecules which are present in Langerhans cells and keratinocytes. Subsequently, CD4+ T-cells activate CD8+ cells through receptor interaction and by the concurrent action of IL-2 and IFN-γ.[7]

IFN-γ in turn, induces the production of TNF-α from keratinocytes as well as an increase in class IIMHC, resulting in increased interaction with helper T-cells. Furthermore, it induces the production of VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 by keratinocytes and dendritic/Langerhans cells, which facilitates lymphocyte adhesion to keratinocytes and results in keratinocyte apoptosis.[8]

Multiple mechanisms have been suggested to explain this apoptotic process: 1. Expression of Fas-ligand on T-cell surface which binds to FAS on keratinocytes. 2. TNF-α secretion by T cells which binds to TNF-α receptor on keratinocytes. 3. Release of cytotoxic molecules like perforin and granzymes B that work together to trigger cell lysis.[7,9]

Clinical manifestations and associations with systemic diseases

LP has a very characteristic, almost pathognomonic clinical image consisting of flat-topped, polygonal, and erythematous or violaceous papules with scaly surface. It may affect many parts of the body, with a predilection for flexor surfaces of wrists and forearms, dorsal hands, shins and genital area.

BLP commonly appears on the oral mucosa and the legs [Fig. 1] with blisters developing near or on pre-existing LP lesions.

Figure 1.

Bullae located on violaceus papules on the legs.

BLP of the nails has also been described in literature.[10] It may present as hemorrhagic crusting, resulting in complete loss of the nail plate and eventually nail atrophy.

An association between nail involvement in BLP and ulcerative lesions on the feet has been established with common involvement of the oral mucosa and cicatricial alopecia.[11,12] In this case, skin grafting of the ulcerated surfaces has been successfully used.

On the other hand, there is a report of BLP developing in the skin graft donor site of a psoriatic patient.[13]

Whereas there are well established associations between LPP and systemic diseases or medications, only a few case reports have been described for BLP.

A case of BLP has been reported to develop after intravenous pyelography and the authors suggested a hypersensitivity reaction to the radiocontrast media as the underlying mechanism.[14]

A report of BLP developing in a patient with systemic sclerosis suggests that immunological features of systemic sclerosis may favor the deposition of immunoglobulin at the dermo-epidermal junction.[15]

Development of BLP has also been described in association with scabies in a child[16] as well as with hepatitis B vaccine, with concurrent involvement of the nails.[17]

Differential diagnosis

BLP should be distinguished from LPP. LPP is considered by some investigators as a combination between LP and bullous pemphigoid (BP).[18] It has been described in adults as well as in children.

In LPP, large tense blisters and/or bullae form de novo on previously intact skin or on pre-existing LP lesions with acute onset and often generalized appearance. Occasionally in LPP bullae may develop only on LP lesions without involvement of the perilesional skin, making difficult the clinical differentiation between LPP and BLP.

The possibility of drug-induced BLP or LP should be thoroughly investigated and excluded in all BLP cases.[19]

Histology

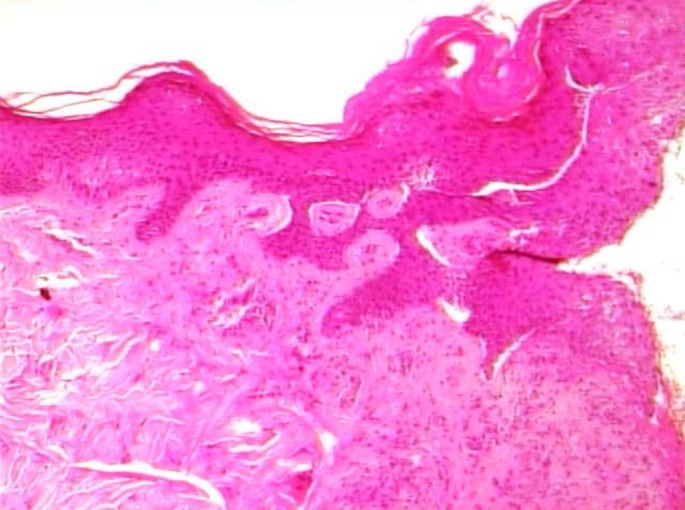

Early in the disease process, the increased number of epidermal Langerhans cells leads to a superficial perivascular infiltrate on the dermo-epidermal junction. The characteristic histopathological features of LP consist of hyperkeratosis, increased granular cell layer, acanthosis with a so-called "sawtooth" appearance, liquefaction of basal cell layer and presence of band-like inflammatory cell infiltrate at the dermo-epidermal junction [Fig. 2].

Figure 2.

Histopathology from a lichen planus lesion with hyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis and sawtooth-like acanthosis (H&E, ×40).

Apoptotic or dyskeratotic keratinocytes, known as Colloid or Civatte bodies can be found at the lower dermis and superficial epidermis.[20] Vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer is typical and results in separated spaces between the epidermis and the dermis, known as "Max-Joseph spaces".[21] Often there is presence of pigment incontinence with numerous dermal macrophages.

In BLP there is an extensive inflammatory infiltrate, with formation of large Max-Joseph spaces that alters the dermoepidermal junction and causes liquefactive eruption of the basal layer cells especially in longstanding lesions but also in normal looking perilesional skin. As a consequence, there is formation of tense bullae or vesiculobullous lesions that are intrabasal due to separation of basal layer cells from the underlying basal membrane. In such cases the rest histological findings are typical of LP.

In direct immunofluoresence there is globular IgM deposition and occasionally IgG and IgA that corresponds to apoptotic epidermal cells or else Colloid Bodies at the lower epidermis with fibrin deposition at the dermoepidermal junction.

Histology is crucial for differentiating BLP from LPP. In LPP there is formation of sub-epidermal bullae without histologic evidence of LP or occasionally with findings resembling LP.[22] Direct immunofluoresence shows linear deposition of IgG and C3 along the dermoepidermal junction.[23,24] Immuno-electron microscopic studies show this deposition to be localized at the base of the bulla, in contrast to BLP where it appears to be on its roof.[25]

As in bullous pemphigoid (BP), there are circulating IgG autoantibodies against 180kDa BP antigen and specifically against its major extracellular non-collagenic part. No antibodies have been detected against 230kDa BP antigen, collagen type VII or laminin 7.[26]

The etiology of BLP remains obscure. It has been suggested that the destruction of the basal cell layer from the extensive lymphocytic infiltrate uncovers hidden epidermal antigens that promote the production of autoantibodieswith the consequent formation of bullae.[18]

Treatment

There is no established treatment of choice and no clearly effective treatment for BLP. Considering that BLP is a hyper-reactive form of LP, topical potent corticosteroids have been used empirically.[27]

Oral betamethasone minipulse therapy has been described to be effective formoderate to severe oral BLP.[28,29] Systemic corticosteroids are considered second line treatments for lichen planus and are reserved for severe cases refractory to local treatments.[30]

Dapsone has also been proved to be efficacious, especially in pediatric BLP.[31,32] A case of resistant hypertrophic BLP responded to treatment with mycophenolatemofetil.[33] Topical application of tretinoin 0.025% in combination with triamcinolone 0.1% has also been used successfully for treating lichen planus with bullous manifestation on the lip.[34] Antimalarial drugs have been indicated as a possible treatment option.[35] Recently, we described the first case of BLP treated successfully with acitretin monotherapy.[36]

Further studies and case series with larger number of patients would significantly contribute to the establishment of a treatment standard and guidelines.

Conclusion

BLP represents a rare form of LP characterized by the development of bullae on LP lesions. The formation of bullae results from extensive inflammation leading to exaggerated epidermal damage. There are not established treatment strategies for BLP. Topical potent steroids are commonly used. Other treatment options based on random observations and single cases include oral steroids, dapsone, mycophenolate mofetil and acitretin.

References

- Pinkus H. Lichenoid tissue reactions. A speculative review of the clinical spectrum of epidermal basal cell damage with special reference to erythema dyschromicum perstans. Arch Dermatol. 1973;107:840–846. doi: 10.1001/archderm.107.6.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Chen S, Liu Z, Tao J, Wang C, Zhou Y. Familial bullous lichen planus (FBLP): Pedigree analysis and clinical characteristics. J Cutan Med Surg. 2005;9:217–222. doi: 10.1007/s10227-005-0146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Yan X, Yang L, Zhang J, Tian J, Li J, Wang C, Tu Y. A retrospective and comparative study of familial and non-familial bullous lichen planus. Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2007;27:336–338. doi: 10.1007/s11596-007-0331-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou XJ, Sugerman PB, Savage NW, Walsh LJ, Seymour GJ. Intra-epithelial CD8+ T cells and basement membrane disruption in oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 2002;31:23–27. doi: 10.1046/j.0904-2512.2001.10063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scully C, Beyli M, Ferreiro MC, Ficarra G, Gill Y, Griffiths M, Holmstrup P, Mutlu S, Porter S, Wray D. Update on oral lichen planus: etiopathogenesis and management. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1998;9:86–122. doi: 10.1177/10454411980090010501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farthing PM, Matear P, Cruchley AT. The activation of Langerhans cells in oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 1990;19:81–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1990.tb00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roopashree MR, Gondhalekar RV, Shashikanth MC, George J, Thippeswamy SH, Shukla A. Pathogenesis of oral lichen planus--a review. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39:729–734. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira PA, Carneiro S, Ramos-e-Silva M. Oral lichen planus: an update on its pathogenesis. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:1005–1010. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastelan M, Prpić Massari L, Gruber F, Zamolo G, Zauhar G, Coklo M, Rukavina D. The role of perforin-mediated apoptosis in lichen planus lesions. Arch Dermatol Res. 2004;296:226–230. doi: 10.1007/s00403-004-0512-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khullar G, Handa S, De D, Saikia UN. Bullous lichen planus of the nails. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:674–675. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.5701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cram DL, Kierland RR, Winkelmann RK. Ulcerative lichen planus of the feet. Bullous variant with hair and nail lesions. Arch Dermatol. 1966;93:692–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner RK, Johnson HH Jr, Binkley GW. Bullous lichen planus with onychatrophy. AMA Arch Derm. 1955;71:636–637. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1955.01540290076019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inalöz HS, Patel G, Holt PJ. Bullous lichen planus arising in the skin graft donor site of a psoriatic patient. J Dermatol. 2001;28:43–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2001.tb00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald MH, Halevy S, Livni E, Feuerman EJ. Bullous lichen planus after intravenous pyelography. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:512–513. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)80365-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlicz-Kowalczuk ZA, Torzecka JD, Kot M, Dziankowska-Bartkowiak B. Atypical clinical presentation of lichen planus bullous in a systemic sclerosis patient. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2016;33:389–391. doi: 10.5114/ada.2016.62848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlotmann K, Neumann NJ, Schuppe HC, Ruzicka T, Lehmann P. Scabies--provoked bullous lichen planus in a child. Hautarzt. 1998;49:929–931. doi: 10.1007/s001050050850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miteva L. Bullous lichen planus with nail involvement induced by hepatitis B vaccine in a child. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:142–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis AL, Bhogal BS, Whitehead P, Frith P, Murdoch ME, Leigh IM, Wojnarowska F. Lichen planus pemphigoides: its relationship to bullous pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 1991;125:263–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1991.tb14753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel N. Cutaneous lichen planus: A systematic review of treatments. J Dermatolog Treat. 2015;26:280–283. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2014.933167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt H. Frequency, duration and localization of lichen planus. A study based on 181 patients. Acta Derm Venereol. 1961;41:164–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roustan G, Hospital M, Villegas C, Sanchez Yus E, Robledo A. Lichen planus with predominant plasma cell infiltrate. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:311–314. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199406000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camisa C, Olsen RG, Yohn JJ. Differentiating bullous lichen planus and lichen planus pemphigoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:1164–1166. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawkrodger DJ, Stavropoulos PG, McLaren KM, Buxton PK. Bullous lichen planus and lichen planus pemphigoides--clinico-pathological comparisons. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1989;14:150–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1989.tb00914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swale VJ, Black MM, Bhogal BS. Lichen planus pemphigoides: two case reports. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1998;23:132–135. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.1998.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prost C, Tesserand F, Laroche L, Dallot A, Verola O, Morel P, Dubertret L. Lichen planus pemphigoides: an immuno-electron microscopic study. Br J Dermatol. 1985;113:31–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1985.tb02041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon KH, Kim SC, Kang DS, Lee IJ. Lichen planus pemphigoides with circulating autoantibodies against 200 and 180 kDa epidermal antigens. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:212–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebwohl M. Lichen planus. In: Treatment of skin diseases Comprehensive therapeutic strategies (Lebwohl M, Heymann W, Berth-Jones J, Coulson I, eds), 4th ed. Elsevier Sauders; 2014. pp. 395–398. [Google Scholar]

- Manousaridis I, Manousaridis K, Peitsch WK, Schneider SW. Individualizing treatment and choice of medication in lichen planus: a step by step approach. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:981–991. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A, Khaitan BK, Verma KK, Singh MK. Generalised and bullous lichen planus treated successfully with oral mini-pulse therapy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1999;65:303–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asch S, Goldenberg G. Systemic treatment of cutaneous lichen planus: an update. Cutis. 2011;87:129–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwee DJ, Dufresne RG, Ellis DL. Childhood bullous lichen planus. Pediatr Dermatol. 1987;4:325–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1987.tb00801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camisa C, Neff JC, Rossana C, Barrett JL. Bullous lichen planus: diagnosis by indirect immunofluorescence and treatment with dapsone. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14:464–469. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)70058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nousari HC, Goyal S, Anhalt GJ. Successful treatment of resistant hypertrophic and bullous lichen planus with mycophenolate mofetil. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:1420–1421. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.11.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tuyll van Serooskerken AM, van Marion AM, de Zwart-Storm E, Frank J, Poblete-Gutiérrez P. Lichen planus with bullous manifestation on the lip. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46 Suppl 3:25–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chyl-Surdacka KM, Przepiórka-Kosińska J, Gerkowicz A, Krasowska D, Chodorowska G. Application of antimalarial medications in the treatment of skin diseases. Przegl Dermatol. 2016;103:316–322. [Google Scholar]

- Rallis E, Liakopoulou A, Christodoulopoulos C, Katoulis A. Successful treatment of bullous lichen planus with acitretin monotherapy. Review of treatment options for bullous lichen planus and case report. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2016;10:62–64. doi: 10.3315/jdcr.2016.1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]