Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVE

Night teams of hospital providers have become more common in the wake of resident physician duty hour changes. We sought to examine relationships between nighttime communication and parents’ inpatient experience.

METHODS

We conducted a prospective cohort study of parents (n = 471) of pediatric inpatients (0–17 years) from May 2013 to October 2014. Parents rated their overall experience, understanding of the medical plan, quality of nighttime doctors’ and nurses’ communication with them, and quality of nighttime communication between doctors and nurses. We tested the reliability of each of these 5 constructs (Cronbach’s α for each >.8). Using logistic regression models, we examined rates and predictors of top-rated hospital experience.

RESULTS

Parents completed 398 surveys (84.5% response rate). A total of 42.5% of parents reported a top overall experience construct score. On multivariable analysis, top-rated overall experience scores were associated with higher scores for communication and experience with nighttime doctors (odds ratio [OR] 1.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.12–3.08), for communication and experience with nighttime nurses (OR 6.47; 95% CI, 2.88–14.54), and for nighttime doctor–nurse interaction (OR 2.66; 95% CI, 1.26–5.64) (P < .05 for each). Parents provided the highest percentage of top ratings for the individual item pertaining to whether nurses listened to their concerns (70.5% strongly agreed) and the lowest such ratings for regular communication with nighttime doctors (31.4% excellent).

CONCLUSIONS

Parent communication with nighttime providers and parents’ perceptions of communication and teamwork between these providers may be important drivers of parent experience. As hospitals seek to improve the patient-centeredness of care, improving nighttime communication and teamwork will be valuable to explore.

Patient and family experience is an important measure of the quality of inpatient care. Poor patient experience is associated with negative patient outcomes, including illness recovery and treatment adherence.1,2 Patient experience scores are also increasingly being linked to reimbursements and assessments of hospital performance.3,4

Parents’ communications with providers (doctors and nurses) are important predictors of their experience.5–9 However, parents’ communication with nighttime providers in particular has not been well studied. Communication at night may fundamentally differ from communication during the day. Staffing levels are typically lower,10,11 provider roles differ, and patients may be cared for by providers who know them less well (especially given recent reductions in consecutive resident physician duty hours).12–14 Communication may also be adversely affected by sleep deprivation and circadian misalignment15–18 as well as parental anxiety. Therefore, we sought to explore the relationships between nighttime communication and parent experience of care during hospitalization by analyzing rates and predictors of parent-reported “top-box” responses (defined as the most positive response option in a scale) to experience questions in a cohort of hospitalized children.

METHODS

Data, Setting, and Study Population

We conducted a prospective cohort study of parents of a randomly selected subset of children (0–17 years) before anticipated discharge from 2 general pediatric units at Boston Children’s Hospital between May 2013 and October 2014. We included general pediatric, “short stay” (patients with straightforward illnesses), and subspecialty (eg, adolescent, immunology, hematology, rheumatology) patients. Research assistants administered written surveys to parents on weekday (Monday–Thursday) evenings. After explaining instructions and answering questions, research assistants left surveys with parents to complete. Research assistants checked in with families 2 to 3 times that evening, or the next morning if requested, to collect completed surveys. We obtained verbal consent from parents by using a study information sheet. We used hospital administrative data to obtain patient demographic and clinical characteristics. Our hospital institutional review board approved the study.

Exclusions

Given limited nighttime interpreter resources, we included only English-speaking parents. To ensure that parents had sufficient time to assess nighttime communication, we included only parents of patients who had spent ≥2 nights in the hospital. We excluded parents of patients “boarding” on the inpatient unit awaiting psychiatric placement, in state custody, or ≥18 years old.

Survey Development

We developed a survey to assess overall inpatient experience and parent experience regarding nighttime communication with and between providers. Our survey included 29 closed questions with a 5-point Likert scale to assess communication and experience. Questions covered 5 distinct constructs: (1) parent understanding of the medical plan, (2) parent communication and experience with nighttime doctors, (3) parent communication and experience with nighttime nurses, (4) parent perceptions of nighttime interaction between doctors and nurses, and (5) parent overall experience of care during hospitalization. We validated the reliability of each construct by calculating a Cronbach’s α (α >.8 for each).

We also included in the survey an open question asking whether parents had anything else to share about communication during the hospitalization and 10 parent demographic questions. We designed this survey with the input of family partners and a survey methodologist. We cognitively tested and piloted the instrument in the study units before data collection.

Outcome Measure

Our primary outcome was parent-reported “top-box” overall experience of care during hospitalization (a dichotomous outcome generated from Construct 5). The top-box refers to the most positive response to a survey question. In our survey, items within the overall experience construct included 6 questions that used an agreement scale (top-box = strongly agree) and one that used a quality scale (top-box = excellent). Responses were subsequently coded onto a 5-point scale for analysis (eg, excellent and strongly agree responses were assigned a score of 5). Parents were considered to have top-box overall experience if they had a score of 5 out of 5 for all items in this construct.

Predictors of Top-Box Overall Experience

We examined the relationship between mean scores for each construct (Constructs 1–4) and our dichotomous top-box overall experience outcome (Construct 5). We assessed which parent and patient characteristics were associated with overall top-box experience. We evaluated parent age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, income, and primary language based on parent survey responses. We evaluated patient age, insurance, length of stay, and complex chronic condition (CCC) count based on hospital administrative data. The CCC system uses International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes to identify medically complex children. It uses these codes to capture “any medical condition that can be reasonably expected to last at least 12 months (unless death intervenes) and to involve either several different organ systems or 1 organ system severely enough to require specialty pediatric care and probably some period of hospitalization in a tertiary care center.”19 Mean construct scores, age, and length of stay were analyzed as continuous predictors; all other predictors were dichotomized.

Statistical Analyses

We performed a descriptive analysis of parent and patient characteristics by using percentages for categorical variables and means (SDs) for continuous variables. For survey questions pertaining to parent-reported communication and experience, we calculated mean scores (SDs) for each of the 5 constructs and for the 29 individual items within these constructs. However, for the purposes of modeling relationships, given the large number of survey questions, we opted to examine aggregate constructs rather than individual items.

To identify factors associated with top-box overall experience (our primary outcome), we dichotomized the sample into a top-box overall experience group (a score of 5 out of 5 for all items within the overall experience construct [Construct 5]) and a non–top-box group.

For bivariate analysis, we assessed the association of categorical sociodemographic and clinical factors across the 2 groups by using the χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests where appropriate. We used the analysis of variance test to assess differences between the 2 groups in mean scores for Constructs 1–4 and the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test to assess differences in nonparametric continuous variables (patient age, length of stay). Covariates with a P of <.20 in the bivariate analyses were added into the multivariable logistic regression model. A P of <.05 was considered statistically significant. We also performed a content analysis with clustering according to theme on text from the open-ended question asking whether parents had anything else to share about communication. We collected and managed study data by using REDCap (REDCap Consortium, Nashville, TN).20 We performed analyses by using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Among eligible parents, 471 (98.9%) consented to participate in the study, and 398 completed surveys (84.5% response rate). Parents were predominantly female (69.1%), white (52.0%), primarily English-speaking (83.4%), college-educated (66.6%), with a mean age of 36.8 years (SD 8.9); 44.0% reported an annual household income ≥$50 000. Patients were predominantly ≤5 years old (57.3%), white (53.0%), and non–publicly insured (61.5%), with no CCCs (73.6%) and a median length of stay of 2.6 days (interquartile range 1.9–4.1) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Parent and Patient Characteristics (n = 398)

| Parent Characteristicsa | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Parent age, y, mean (SD) | 36.8 (8.9) |

| Parent gender | |

| Female | 275 (69.1) |

| Male | 62 (15.6) |

| Missing | 61 (15.3) |

| Relationship to patient | |

| Parent | 327 (82.2) |

| Other | 12 (3.0) |

| Missing | 59 (14.8) |

| Parent race and ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 207 (52.0) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 35 (8.8) |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 14 (3.5) |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 16 (4.0) |

| Hispanic | 64 (16.1) |

| Missing | 62 (15.6) |

| Parent primary language | |

| English | 332 (83.4) |

| Other | 66 (16.6) |

| Parent education | |

| Any college | 265 (66.6) |

| Other | 68 (17.1) |

| Missing | 65 (16.3) |

| Annual household income | |

| <$30 000 | 87 (21.9) |

| $30 000–$49 999 | 37 (9.3) |

| $50 000–$74 999 | 27 (6.8) |

| $75 000–$99 999 | 28 (7.0) |

| >$100 000 | 120 (30.2) |

| Missing | 99 (24.9) |

|

| |

| Patient Characteristicsb | |

|

| |

| Patient insurance | |

| Nonpublic | 243 (61.5) |

| Public | 152 (44.0) |

| Patient gender | |

| Female | 200 (50.3) |

| Male | 198 (49.8) |

| Patient age, y, mean (SD) | 5.5 |

| <1 | 116 (29.2) |

| 1–5 | 112 (28.1) |

| 6–13 | 114 (28.6) |

| 14–17 | 56 (14.1) |

| CCC countc | |

| 0 | 293 (73.6) |

| 1 | 78 (19.6) |

| 2 | 20 (5.0) |

| 3+ | 7 (1.8) |

| Length of stay, median (interquartile range) | 2.6 (1.9–4.1) |

Based on survey response data.

Based on hospital administrative data.

The CCC system uses International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnoses codes to identify medical conditions that can be expected to last ≥12 mo and to involve several different organ systems or 1 system severely enough to necessitate specialty pediatric care and a period of hospitalization in a tertiary care left.19

Top-Box Experience Scores by Construct and by Individual Item

Overall, 42.5% (n = 169) of parents reported top-box overall experience (a score of 5 out of 5 on all items in the overall experience construct [Construct 5]). Mean (SD) construct scores ranged from 4.05 (0.88) for the nighttime doctor experience and communication construct to 4.59 (0.51) for the overall experience construct (our outcome) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Parent-Reported Communication and Experience Scores by Item and by Construct

| Construct 1: Understanding of Medical Plan | n | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. I completely understood the overall reason for my child’s hospitalization. | 395 | 4.55 (0.87) |

| 2. I was always told the overnight medical plan for my child. | 396 | 4.29 (0.93) |

| 3. I always understood the overnight medical plan for my child. | 393 | 4.28 (0.97) |

| 4. In general, I agreed with the overnight medical plan for my child. | 387 | 4.61 (0.69) |

| 5. I was given an update about my child between 3 pm and midnight each day. | 388 | 4.54 (0.82) |

| 6. I was always updated about what changes to look out for with my child overnight. | 388 | 4.16 (0.89) |

| Overall medical plan construct score | 398 | 4.40 (0.64) |

|

| ||

| Construct 2: Communication and Experience With Nighttime Doctors | ||

|

| ||

| 7. I regularly communicated with my child’s nighttime doctors. | 389 | 3.84 (1.09) |

| 8. I always had a chance to ask my nighttime doctors questions about my child. | 385 | 4.01 (1.06) |

| 9. How would you rate the availability of your child’s nighttime doctors? | 380 | 3.89 (1.14) |

| 10. How would you rate the quality of communication you had with your child’s nighttime doctors? | 382 | 3.93 (1.18) |

| 11. My child’s nighttime doctors always seemed to know the medical plan for my child. | 385 | 4.25 (0.86) |

| 12. My child’s nighttime doctors and I had the same understanding of my child’s medical plan. | 362 | 4.53 (0.72) |

| 13. How well did your child’s daytime and nighttime doctors coordinate with one another? | 353 | 4.14 (0.92) |

| Overall nighttime doctors construct score | 391 | 4.05 (0.88) |

|

| ||

| Construct 3: Communication and Experience With Nighttime Nurses | ||

|

| ||

| 14. I regularly communicated with my child’s nighttime nurses. | 394 | 4.54 (0.72) |

| 15. I always had a chance to ask my nighttime nurses questions about my child. | 393 | 4.61 (0.66) |

| 16. How would you rate the availability of your child’s nighttime nurses? | 393 | 4.50 (0.74) |

| 17. How would you rate the quality of communication you had with your child’s nighttime nurses? | 391 | 4.52 (0.74) |

| 18. My child’s nighttime nurses always seemed to know the medical plan for my child. | 393 | 4.55 (0.62) |

| 19. My child’s nighttime nurses and I had the same understanding of my child’s medical plan. | 391 | 4.67 (0.57) |

| 20. How well did your child’s daytime and nighttime nurses coordinate with one another? | 387 | 4.42 (0.80) |

| Overall nighttime nurses construct score | 394 | 4.54 (0.55) |

|

| ||

| Construct 4: Nighttime Interaction Between Doctors and Nurses | ||

|

| ||

| 21. My child’s nighttime doctors and nurses had the same understanding as one another of my child’s medical plan. | 374 | 4.61 (0.62) |

| 22. How would you rate teamwork among your nighttime doctors and nurses? | 377 | 4.37 (0.83) |

| Overall nighttime interaction construct score | 378 | 4.49 (0.67) |

|

| ||

| Construct 5: Overall Experience | ||

|

| ||

| 23. How would you rate the overall quality of care your child received? | 393 | 4.55 (0.77) |

| 24. I felt like my child’s doctors valued my input about my child. | 388 | 4.55 (0.65) |

| 25. I felt like my child’s doctors listened to my concerns about my child. | 393 | 4.62 (0.57) |

| 26. I felt like my child’s doctors thought of me as an important part of the health care team caring for my child. | 393 | 4.51 (0.71) |

| 27. I felt like my child’s nurses valued my input about my child. | 389 | 4.63 (0.59) |

| 28. I felt like my child’s nurses listened to my concerns about my child. | 390 | 4.66 (0.58) |

| 29. I felt like my child’s nurses thought of me as an important part of the health care team caring for my child. | 386 | 4.63 (0.62) |

| Overall experience construct score | 398 | 4.59 (0.51) |

All scores represent responses to questions with 5-point Likert scale responses. 1 = lowest quality response (never for items 4, 5, 12, 19, 21; poor for items 9, 10, 13, 16, 17, 20, 22, 23; and strongly disagree for all other items). 5 = highest quality response (always, excellent, or strongly agree for the corresponding items). Constructs 1–4 are predictors, and Construct 5 was used to generate the primary outcome.

Mean (SD) construct scores for parents who reported top-box overall experience as compared with parents who did not report top-box overall experience were 4.69 (0.50) vs 4.19 (0.64) for understanding of the medical plan (Construct 1), 4.55 (0.68) vs 3.68 (0.83) for communication and experience with nighttime doctors (Construct 2), 4.85 (0.30) vs 4.31 (0.59) for communication and experience with nighttime nurses (Construct 3), and 4.87 (0.37) vs 4.19 (0.71) for interaction between nighttime doctors and nurses (Construct 4) (P < .001 for all).

Individual items for which parents provided highest ratings included feeling that nurses listened to their concerns (70.5% strongly agreed), having the same understanding of the medical plan as nighttime nurses (70.3% always), and feeling that nurses thought of them as an important part of the health care team (69.2% strongly agreed). Items for which parents reported lowest ratings included regular communication with nighttime doctors (31.4% strongly agreed), being updated about what changes to look out for overnight (41.0% strongly agreed), quality of communication with nighttime doctors (43.7% excellent), and coordination between daytime and nighttime doctors (43.9% excellent).

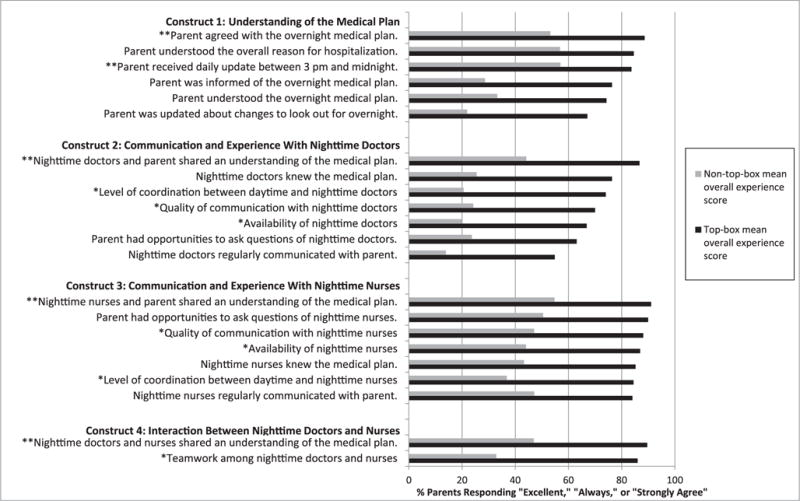

More than 80% of parents who reported top-box overall experience provided top ratings for coordination between daytime and nighttime nurses and for teamwork between nighttime doctors and nurses, as compared with <40% of parents who did not report top-box overall experience (P < .05 for both) (Fig 1).

FIGURE 1.

Individual survey item responses for parents with top-box overall experience versus without. Percentage of parents responding “excellent” (*), “always” (**), or “strongly agree” (all other items) to individual survey items, stratified by parents who reported a top-box overall experience construct score versus those who did not (P < .001 for all items). Each item used a 5-point Likert scale.

Bivariate predictors of top-box overall experience included patient age and increased scores for Constructs 1–4: parent understanding of the medical plan, communication and experience with nighttime doctors, communication and experience with nighttime nurses, and interaction between nighttime doctors and nurses (P < .05 for all) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Bivariate and Multivariable Predictors of Top-Boxa Overall Experience

| Characteristic | Bivariate

|

Multivariable

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Mean construct scoreb | ||||||

| Construct 1: Understanding of Medical Plan | 6.98 | 4.15–11.76 | <.001 | 1.46 | 0.80–2.64 | .22 |

| Construct 2: Communication and Experience With Nighttime Doctors | 5.27 | 3.60–7.71 | <.001 | 1.86 | 1.12–3.08 | .02 |

| Construct 3: Communication and Experience With Nighttime Nurses | 20.66 | 10.17–41.99 | <.001 | 6.47 | 2.88–14.54 | <.001 |

| Construct 4: Interaction Between Nighttime Doctors and Nurses | 12.36 | 6.92–22.06 | <.001 | 2.66 | 1.26–5.64 | .01 |

| Child’s age | ||||||

| 1-y increase | 1.04 | 1.01–1.08 | .02 | 1.06 | 1.01–1.11 | .02 |

| c statistic = 0.872 | ||||||

Parents were considered to have top-box overall experience if they had a score of 5 out of 5 for all items within this construct.

Ranged from 1 to 5 (5 = best response).

Multivariable predictors (odds ratio [OR] and 95% confidence interval [CI]) of top-box overall experience included increased patient age (OR 1.06; 95% CI, 1.01–1.11) and higher mean scores for Constructs 2–4: communication and experience with nighttime doctors (OR 1.86; 95% CI, 1.12–3.08), communication and experience with nighttime nurses (OR 6.47; 95% CI, 2.88–14.54), and perception of nighttime doctor–nurse interaction (OR 2.66; 95% CI, 1.26–5.64) (Table 3).

Narrative Comments

Narrative comments (n = 109) provided by parents in response to the open-ended item asking whether they had anything else to share about communication covered a number of themes (see Table 4 for illustrative quotes for each). The majority of parents relayed positive comments (n = 64) that ranged from general to detailed comments about respectfulness, clarity of communication, experience with staff, teamwork, attentiveness, patient and family involvement, and thoroughness. However, some expressed concerns about communication with their doctors and nurses (n = 36). These included concerns related to completeness and quality of information, physical absence of nighttime doctors, delays in communication, receiving conflicting information, frustration at needing to repeat information, feeling dismissed, and interpersonal concerns. In addition, several parents (n = 9) provided suggestions for improving communication. These included tools to help identify staff and requests to provide regular nighttime updates, provide written summaries, and generally increase communication.

TABLE 4.

Parent Narrative Comments About Inpatient Communication (n = 109)

| A. Positive Experiences (n = 64) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Theme | Example(s) |

| General experience | “They are wicked awesome!” |

| Respectfulness | “Everybody was very polite and made me feel like my son was a top priority and not just a patient.” |

| Experience with nurses and physicians | “Doctor and nurse did a wonderful job!” |

| Experience with nurses | “The nurses show us a very professional and friendly approach. They are always available all the time we need them.” |

| Clarity of communication | “All doctors + nurses knew her plan, updated me with changes + if there were changes to her plan everyone knew it. Great communication!!” |

| Experience with specific individuals | “Loved the Diabetes Center Manager.” |

| Teamwork | “Excellent teamwork.” |

| Attentiveness | “Very attentive and responsive.” |

| Involvement of patient and family in care | “The entire health care team have been phenomenal in their attentiveness to [ ]. Involving the patient in [the] planning process and decision making was a great help to ease his mind.” |

| Thoroughness | “The drs + nurses have provided my child with excellent care. I feel that they have been very thorough.” |

|

| |

| B. Concerns (n = 36) | |

|

| |

| Theme | Example(s) |

|

| |

| Completeness and quality of communication | “The only slight concern I had was there was slight confusion between the nurses relating to the fluid intake which required clarification with the doctors in the early stages.” |

| Absence of nighttime doctors | “I never saw a nighttime doctor. No one ever explained any plan of care.” |

| Delays in communication | “I did not get a chance to see the doctors in the morning before I had to leave (9:30 am). I was hoping to get lab results.” |

| Conflicting communication |

“We got conflicting opinions from 2 daytime doctors and didn’t know who to listen to.” “Daytime plan was sometimes conflicting between doctors and nurses.” |

| Interpersonal concerns | “Night doctor bedside manner needs to improve … you could tell by her eyes being closed she did not like being corrected.” |

| Feeling dismissed |

“I felt like she needed an anti-inflammatory, however doctors totally disregarded me. … I asked for Dr. [ ] because my family has history w/him. They told me I could seek him out on my own. However, two days prior to discharge he happened to be on the ‘Team’ that came to visit. He wanted to know why my daughter hadn’t received any steroids for inflammation?” “The care team doesn’t always get back to me with answers about every concern I had.” |

| Daytime versus nighttime | “I felt that the daytime doctors were much more involved whereas the nighttime doctors were there just to make sure that the game plan established by the day doctors went smoothly.” |

| Repetition | “It seemed as though none of the teams shared information before meeting us for the first time so we were forced to repeat ourselves every time about basic information.” |

|

| |

| C. Suggestions for Improvement (n = 9) | |

|

| |

| Theme | Example(s) |

|

| |

| Identifying staff |

“It would be helpful to have a final list of the daily doctors, residents and fellows. I always knew nurses’ names.” “Would be nice to have a pt wipe board in the room listing day/date, his current RN + MD’s names and his medical plan for the day, and what approx. time the MD will round next.” “Need to write names on board, so many different healthcare providers. [] started doing it.” |

| Written summaries | “1. A summary sheet of appointments or written on the board. 2. An early explanation, expectation of how long the stay would be would have been nice.” |

| More communication | “There is always room for more communication.” |

| Nighttime updates | “It would be nice if day nurse came in with night nurse at change of shift to introduce and help parents transition to night/day team.” |

| Other |

“I would recommend only discussing serious diagnoses at length if they have been confirmed.” “The pharmacy needs to be more informed of the patients’ med times before the upcoming scheduled med so meds do not arrive onto floor to be given late.” |

Parents’ narrative comments (109/398 responded), organized by category (positive experiences [A], concerns [B], and suggestions for improvement [C]) and theme. Illustrative quotes for each category are provided.

DISCUSSION

We found that parents who experienced suboptimal communication and teamwork at night were much more likely to rate their overall hospital experience poorly. More than 80% of parents who reported top-box overall experience provided top scores for teamwork among nighttime doctors and nurses, as compared with <40% of parents who did not report top-box overall experience. On multivariable analyses, parents’ ratings of their direct communications with doctors and nurses, and their observations of teamwork and communication between doctors and nurses, were significant predictors of top-box overall experience. These findings suggest that improving nighttime communication could be an important, largely underrecognized means by which hospitals could achieve improvements in patient experience.

Parents’ communication with providers is known to affect their ratings of inpatient experience.6,7 Previous studies have not focused on differences between communication during the day and night, however. Over the past decade, hospitals have increasingly moved toward care models in which different teams of providers care for patients by day and by night. Parent communications with nighttime providers, who may be responsible for more than half of care provided in hospitals, may differ from communications with daytime providers given different provider roles and responsibilities at night.

Interestingly, we found that parent experience seemed predicated not only on parent communications at night with physicians and nurses but also on parent perceptions of nighttime communication and teamwork between nurses and physicians. Our study suggests that parents may perceive, to a greater extent than providers realize, problems in interprofessional teamwork and communication that in turn may affect their experience. Thus, our data suggest that in addition to interventions to improve communications between health care providers and parents, initiatives to improve interprofessional (eg, physician–nurse) and intraprofessional (eg, daytime physician–nighttime physician or daytime nurse–nighttime nurse) communication and teamwork may be associated with improved parent experience of care.

Beyond having an impact on parent experience, teamwork and communication interventions may affect patient outcomes. The quality of provider–patient communication predicts treatment adherence.21–24 Physician–nurse interactions are associated with patient mortality and readmissions.25,26 Teamwork has been correlated with patient outcomes27 and quality of care.28,29

An important secondary finding of our study was the absence of nighttime doctors at the bedside. The nighttime doctor construct had the lowest mean score (4.0) of all 5 constructs, and of all individual survey items, parents reported the lowest score for regular communication with nighttime doctors (only 31% strongly agreed). Although parents who reported suboptimal experience had significantly lower scores than their counterparts for all survey items, these differences were particularly marked for items relating to communication with nighttime doctors. For instance, 70% of parents who reported top-box overall experience rated quality of communication with nighttime doctors as excellent, compared with only 24% of parents who did not report top-box overall experience. These results may reflect, in part, night physicians engaging in behind-the-scenes care coordination and communication, of which parents are unaware. Regardless, parent perceptions of physician presence appear to be associated with overall experience.

The narrative comments from parents in our study enable a richer understanding of these findings. For instance, 1 parent remarked that the role of the nighttime doctors seemed merely to ensure that the plan established by the day doctors went smoothly. Although resident physicians in the studied residency program are taught through the I-PASS program that responsibility is fully transferred to them when they assume care at night,30 the realities of discontinuity in coverage, decreased staffing, and increased workload appear to have a continued impact at night. Hospitals seeking to address this challenge will need to contend with cultural change and consider changes in staff logistics and resources.

In contrast, parents seemed to report particularly high scores for experience with nighttime nurses. The nighttime nurse experience construct had a mean score of 4.5, and parents’ highest-rated single item was whether they thought nurses listened to their concerns (71% strongly agreed). Experience with nighttime nurses was also our strongest predictor of overall experience. We found more than a sixfold increase in the odds of having a top-box overall experience for every 1-point increase in the mean nighttime nurse communication and experience construct score. Our study was not designed to directly compare the relative importance of physician, nurse, and physician–nurse factors in informing parent experience, and CIs for these 3 domains overlap. However, our results did preliminarily suggest a particularly important role of the nighttime nurse in shaping overall care experience. This finding is consistent with previous literature31 and may reflect in part the large amount of time nurses often spend at the bedside.

Our study has a number of possible implications warranting additional exploration for how hospitals and providers might improve nighttime communication and thereby improve parent experience. However, rigorously designed intervention studies are needed to determine their effectiveness, ensure feasibility, and avoid unintended negative consequences. Possible interventions warranting future study include targeted initiatives to increase the amount of time spent at the bedside by nighttime physicians earlier in the evening (while parents are awake) and initiatives to allow parents to more clearly identify their daytime and nighttime care teams (eg, through white boards or photo information face sheets32,33). Additional interventions, as suggested by parents in our study, include providing written documentation with updates about the care plan. Also, although a great deal of emphasis has been placed on improving communication at change of shift between daytime and nighttime physicians,30,34–36 our study suggests that efforts to improve interdisciplinary communication, such as teamwork training,37,38 multidisciplinary handoffs34,39 that involve parents,40,41 huddles,42–44 and bedside shift reports,45 may provide additional value. In addition, technology may be leveraged to improve real-time communication between members of the care team, including parents, nurses, and physicians. For instance, secure text messaging46 may be an efficient way to improve communication, even when staffing is low and workload is high. In addition to more studies to ensure their feasibility and effectiveness, many of these interventions require culture change, as well as practical, logistical, and financial support.

We recognize that night is a difficult time for physicians, nurses, and families alike given different roles and priorities compared with daytime care (eg, dealing with emergencies in a larger cohort of patients; provider, patient, and parent sleep).

Nevertheless, these data suggest that the limited time available to night providers is greatly valued by patients as the communication parents have with their night providers and the perceived teamwork between night doctors and nurses may have an important effect on parents’ overall experience. However, any efforts to improve communication at night between patients and providers will need to be sensitive to provider workflow, parent and patient sleep, and parent preferences.

Our study had several limitations. It was conducted at a single, tertiary care children’s hospital among English-speaking, predominantly female, well-educated parents of patients admitted for ≥2 nights, all of which limit generalizability. The experience of parents of patients admitted for less time or in other contexts may vary. Additionally, unlike most parent experience surveys, which are typically mailed to families after discharge, we conducted our survey before discharge, while parents were still in the hospital with their children. Therefore, we were not able to capture the association between the discharge process and parent experience of inpatient hospitalization. This limitation may have biased our study toward higher experience scores. However, our response rates were high. In addition, parents do not have the opportunity to observe all communication between physicians and nurses, so their perceptions may reflect only a portion of such communication or may capture other elements of care. Finally, we were not able to determine causality in this study, and there are probably complex connections between the types of communication captured in our survey constructs that we could not fully explore here. Additional study is needed to examine these relationships in greater detail.

CONCLUSIONS

In an era of increasing reliance on night teams of residents, our study helps fill gaps in the literature about nighttime care in hospitals. It suggests that nighttime communication may be an important driver of parent experience of care and may be an underrecognized area of improvement for providers and hospitals. Targeted interventions that focus on improving teamwork and communication at night have the potential to improve patient experience and other important indicators of care quality.

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT

Communication between parents and providers is an important driver of parent experience of care. The impact of nighttime communication, which has become increasingly relevant after changes in resident physician duty hours, on parent experience is unknown.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Parent communication with nighttime doctors and nurses, and parent perceptions of communication and teamwork between these providers, may be important drivers of parent experience. Efforts to improve nighttime communication, both with parents and between team members, may improve parent experience.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Thomas W. Mangione, PhD, for his assistance with reviewing the survey instrument, parent partners Brenda Allair and Katie Litterer for providing valuable parent perspectives, and all the families and research assistants who participated in this study.

Dr Khan conceptualized and designed the study, obtained funding, acquired data, performed statistical analyses, analyzed and interpreted data, and drafted the initial manuscript; Ms Rogers provided intellectual advice and guidance for the study and obtained funding; Ms Melvin performed statistical analyses and analyzed and interpreted data; Ms Furtak participated in study design, tabulated articles, helped perform the literature review, and provided administrative support; Ms Faboyede participated in study design, acquired data, and helped perform the literature review; Dr Schuster provided intellectual advice and methodological guidance for the study; Dr Landrigan supervised the study, obtained funding, conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted data, and drafted the manuscript; and all authors critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FUNDING: Support for this work was provided by an Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality NRSA T32 HS000063 grant, an Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality K12HS022986 grant, an internal Boston Children’s Hospital Program for Patient Safety and Quality grant, and a Taking on Tomorrow Innovation Award in Community/Patient Empowerment. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the funding sources.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CCC

complex chronic condition

- CI

confidence interval

- OR

odds ratio

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: Dr Landrigan has served as a paid consultant to Virgin Pulse to help develop a Sleep and Health Program. He is supported in part by the Children’s Hospital Association for his work as an executive council member of the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) network. In addition, Dr Landrigan has received monetary awards, honoraria, and travel reimbursement from multiple academic and professional organizations for teaching and consulting on sleep deprivation, physician performance, handoffs, and safety and has served as an expert witness in cases regarding patient safety and sleep deprivation. The other authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Kane RL, Maciejewski M, Finch M. The relationship of patient satisfaction with care and clinical outcomes. Med Care. 1997;35(7):714–730. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199707000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Covinsky KE, Rosenthal GE, Chren MM, et al. The relation between health status changes and patient satisfaction in older hospitalized medical patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(4):223–229. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. HCAHPS: patients’perspectives of care survey. 2014 Sep; Available at: www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/HospitalHCAHPS.html. Accessed June 26, 2015.

- 4.Hospital Compare. Survey of patients’ experiences (HCAHPS) Available at: www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/Data/Overview.html. Accessed May 29, 2015.

- 5.Co JPT, Ferris TG, Marino BL, Homer CJ, Perrin JM. Are hospital characteristics associated with parental views of pediatric inpatient care quality? Pediatrics. 2003;111(2):308–314. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Homer CJ, Marino B, Cleary PD, et al. Quality of care at a children’s hospital: the parent’s perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(11):1123–1129. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.11.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fisher MJ, Broome ME. Parent–provider communication during hospitalization. J Pediatr Nurs. 2011;26(1):58–69. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2009.12.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hart CN, Kelleher KJ, Drotar D, Scholle SH. Parent–provider communication and parental satisfaction with care of children with psychosocial problems. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;68(2):179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nobile C, Drotar D. Research on the quality of parent-provider communication in pediatric care: implications and recommendations. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2003;24(4):279–290. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200308000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Cordova PB, Phibbs CS, Schmitt SK, Stone PW. Night and day in the VA: associations between night shift staffing, nurse workforce characteristics, and length of stay. Res Nurs Health. 2014;37(2):90–97. doi: 10.1002/nur.21582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller AD, Piro CC, Rudisill CN, Bookstaver PB, Bair JD, Bennett CL. Nighttime and weekend medication error rates in an inpatient pediatric population. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(11):1739–1746. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scoglietti VC, Collier KT, Long EL, Bush GPD, Chapman JR, Nakayama DK. After-hours complications: evaluation of the predictive accuracy of resident sign-out. Am Surg. 2010;76(7):682–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Edwards DS, Burge SK, Young RA, Peterson LE, Babb FC. Inpatient hand-offs in family medicine residency programs: a CERA study. Fam Med. 2015;47(5):362–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein MJ, Kim E, Widmann WD, Hardy MAA. A 360 degrees evaluation of a night-float system for general surgery: a response to mandated work-hours reduction. Curr Surg. 2004;61(5):445–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Papp KK, Stoller EP, Sage P, et al. The effects of sleep loss and fatigue on resident-physicians: a multi-institutional, mixed-method study. Acad Med. 2004;79(5):394–406. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200405000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fostick L, Babkoff H, Zukerman G. Effect of 24 hours of sleep deprivation on auditory and linguistic perception: a comparison among young controls, sleep-deprived participants, dyslexic readers, and aging adults. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2014;57(3):1078–1088. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2013/13-0031). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Helm E, Gujar N, Walker MP. Sleep deprivation impairs the accurate recognition of human emotions. Sleep. 2010;33(3):335–342. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.3.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Motomura Y, Kitamura S, Oba K, et al. Sleep debt elicits negative emotional reaction through diminished amygdala–anterior cingulate functional connectivity. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56578. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980–1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1 pt 2 suppl 1):205–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balkrishnan R. Predictors of medication adherence in the elderly. Clin Ther. 1998;20(4):764–771. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(98)80139-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zolnierek KB, Dimatteo MR. Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care. 2009;47(8):826–834. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819a5acc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Svensson S, Kjellgren KI, Ahlner J, Säljö R. Reasons for adherence with antihypertensive medication. Int J Cardiol. 2000;76(2–3):157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(00)00374-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beach MC, Keruly J, Moore RD. Is the quality of the patient–provider relationship associated with better adherence and health outcomes for patients with HIV? J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):661–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00399.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baggs JG, Schmitt MH, Mushlin AI, et al. Association between nurse–physician collaboration and patient outcomes in three intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(9):1991–1998. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199909000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shortell SM, Zimmerman JE, Rousseau DM, et al. The performance of intensive care units: does good management make a difference? Med Care. 1994;32(5):508–525. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199405000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wheelan SA, Burchill CN, Tilin F. The link between teamwork and patients’ outcomes in intensive care units. Am J Crit Care. 2003;12(6):527–534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meterko M, Mohr DC, Young GJ. Teamwork culture and patient satisfaction in hospitals. Med Care. 2004;42(5):492–498. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000124389.58422.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.J Alharbi TS, Olsson LE, Ekman I, Carlström E. The impact of organizational culture on the outcome of hospital care: after the implementation of person-centred care. Scand J Public Health. 2014;42(1):104–110. doi: 10.1177/1403494813500593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Starmer AJ, O’Toole JK, Rosenbluth G, et al. I-PASS Study Education Executive Committee Development, implementation, and dissemination of the I-PASS handoff curriculum: a multisite educational intervention to improve patient handoffs. Acad Med. 2014;89(6):876–884. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johansson P, Oléni M, Fridlund B. Patient satisfaction with nursing care in the context of health care: a literature study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2002;16(4):337–344. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-6712.2002.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dudas RA, Lemerman H, Barone M, Serwint JR. PHACES (Photographs of Academic Clinicians and Their Educational Status): a tool to improve delivery of family-centered care. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(2):138–145. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Unaka NI, White CM, Sucharew HJ, Yau C, Clark SL, Brady PW. Effect of a face sheet tool on medical team provider identification and family satisfaction. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):186–188. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koenig CJ, Maguen S, Daley A, Cohen G, Seal KH. Passing the baton: a grounded practical theory of handoff communication between multidisciplinary providers in two Department of Veterans Affairs outpatient settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(1):41–50. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2167-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Starmer AJ, Spector ND, Srivastava R, Allen AD, Landrigan CP, Sectish TC; I-PASS Study Group I-PASS, a mnemonic to standardize verbal handoffs. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):201–204. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abraham J, Kannampallil T, Patel VL. A systematic review of the literature on the evaluation of handoff tools: implications for research and practice. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(1):154–162. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clancy CM, Tornberg DN. TeamSTEPPS: assuring optimal teamwork in clinical settings. Am J Med Qual. 2007;22(3):214–217. doi: 10.1177/1062860607300616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.King HB, Battles J, Baker DP, et al. TeamSTEPPS: Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, editors. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol 3: Performance and Tools) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joy BF, Elliott E, Hardy C, Sullivan C, Backer CL, Kane JM. Standardized multidisciplinary protocol improves handover of cardiac surgery patients to the intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2011;12(3):304–308. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181fe25a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friesen MA, Herbst A, Turner JW, Speroni KG, Robinson J. Developing a patient-centered ISHAPED handoff with patient/family and parent advisory councils. J Nurs Care Qual. 2013;28(3):208–216. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0b013e31828b8c9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gosdin CH, Vaughn L. Perceptions of physician bedside handoff with nurse and family involvement. Hosp Pediatr. 2012;2(1):34–38. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2011-0008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salas E, Almeida SA, Salisbury M, et al. What are the critical success factors for team training in health care? Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35(8):398–405. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(09)35056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dingley C, Daugherty K, Derieg M, Persing R. Improving patient safety through provider communication strategy enhancements. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, editors. Advances in Patient Safety: New Directions and Alternative Approaches (Vol 3: Performance and Tools) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robertson B, Kaplan B, Atallah H, Higgins M, Lewitt MJ, Ander DS. The use of simulation and a modified TeamSTEPPS curriculum for medical and nursing student team training. Simul Healthc. 2010;5(6):332–337. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3181f008ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reinbeck DM, Fitzsimons V. Improving the patient experience through bedside shift report. Nurs Manage. 2013;44(2):16–17. doi: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000426141.68409.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shapiro JR, Bauer S, Hamer RM, Kordy H, Ward D, Bulik CM. Use of text messaging for monitoring sugar-sweetened beverages, physical activity, and screen time in children: a pilot study. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2008;40(6):385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]