Abstract

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is derived from arachidonic acid, whereas PGE3 is derived from eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) using the same downstream metabolic enzymes. Little is known about the impact of EPA and PGE3 on β-cell function, particularly in the diabetic state. In this work, we determined that PGE3 elicits a 10-fold weaker reduction in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion through the EP3 receptor as compared with PGE2. We tested the hypothesis that enriching pancreatic islet cell membranes with EPA, thereby reducing arachidonic acid abundance, would positively impact β-cell function in the diabetic state. EPA-enriched islets isolated from diabetic BTBR Leptinob/ob mice produced significantly less PGE2 and more PGE3 than controls, correlating with improved glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. NAD(P)H fluorescence lifetime imaging showed that EPA acts downstream and independently of mitochondrial function. EPA treatment also reduced islet interleukin-1β expression, a proinflammatory cytokine known to stimulate prostaglandin production and EP3 expression. Finally, EPA feeding improved glucose tolerance and β-cell function in a mouse model of diabetes that incorporates a strong immune phenotype: the NOD mouse. In sum, increasing pancreatic islet EPA abundance improves diabetic β-cell function through both direct and indirect mechanisms that converge on reduced EP3 signaling.

Introduction

A diet high in essential n-3 (also called ω-3 or omega-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) is proposed to be beneficial in chronic conditions such as diabetes; yet, direct confirmation of these effects and the mechanisms mediating them remains elusive (1). Intact PUFAs can activate β-cell G-protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) that stimulate insulin secretion (2). However, PUFAs are metabolized, and the regulatory action of their bioactive compounds, particularly those of the 3-series, on β-cell biology is not well understood.

Previous work from our laboratory and others’ demonstrates an increase in the production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), an eicosanoid derived from the n-6 PUFA arachidonic acid (AA), and/or its receptor EP3 from islets isolated from diabetic mice and humans with diabetes (3–8) (see Table 1 for a list of abbreviations of all fatty acid species, metabolites, metabolic enzymes, and signaling enzymes used in this study). Upregulation of this signaling pathway actively contributes to diabetic β-cell dysfunction (3,6,7). The n-3 PUFA, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), competes with AA for the same eicosanoid biosynthetic enzymes, yielding PGE3 instead of PGE2. We therefore questioned whether shifting plasma membrane PUFA composition to favor EPA would alter eicosanoid production and limit EP3 signaling, resulting in enhanced β-cell function in two mouse models of diabetes: the BTBR-Ob mouse, a strong model of obesity-linked type 2 diabetes (T2D), and the NOD mouse, a strong model of immune-mediated type 1 diabetes (T1D).

Table 1.

Abbreviations for fatty acid species, metabolites, and metabolic/signaling enzymes discussed in this study

| Abbreviation | Full name | Other names | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| AA | Arachidonic acid | ARA | An omega-6 PUFA derived from LA |

| 20:4 (ω-6) | |||

| 20:4 (n-6) | |||

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic acid | Icosapentaneoic acid | An omega-3 PUFA derived from ALA |

| 20:5 (ω-3) | |||

| 20:5 (n-3) | |||

| LA | Linoleic acid | 18:2 (ω-6) | An essential omega-6 PUFA that can be converted to AA |

| 18:2 (n-6) | |||

| ALA | α-Linolenic acid | 18:3 (ω-3) | An essential omega-3 PUFA that can be converted to EPA |

| 18:3 (n-3) | |||

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 | Dinoprostone | AA metabolite |

| PGE3 | Prostaglandin E3 | Delta(17)-PGE1 | EPA metabolite |

| Pla2g4a | Phospholipase A2 group IVa | Cytosolic phospholipase A2 | Catalyzes hydrolysis of membrane phospholipids to release AA or EPA; inducible by Ca2+ |

| Pla2g6 | Phospholipase A2 group 6 | Calcium-independent phospholipase A2 | Catalyzes hydrolysis of membrane phospholipids to release AA or EPA |

| Ptgs1 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1 | COX-1 | Converts free AA to the intermediate, PGH2, and free EPA to the intermediate, PGH3 |

| Cyclooxygenase-1 | |||

| Prostaglandin G/H synthase 1 | |||

| Prostaglandin H2 synthase 1 | |||

| Ptgs2 | Prostaglandin endoperoxidase synthase 2 | COX-2 | Converts free AA to the intermediate, PGH2, and free EPA to the intermediate, PGH3; also termed inducible COX, although in β-cells, it is constitutively expressed |

| Cyclooxygenase-2 | |||

| Prostaglandin G/H synthase 2 | |||

| Prostaglandin H2 synthase 2 | |||

| Ptges | Prostaglandin E synthase | Converts PGH2 into PGE2 and PGH3 into PGE3; three isoforms encoded by different genes exist: Ptges, Ptges2, and Ptges3 | |

| EP1 | Prostaglandin E2 receptor 1 | Ptger1 (gene name) | GPCR for E-series prostanoids including PGE2 and PGE3; couples primarily to Gq subfamily G proteins to impact Ca2+ dynamics and phospholipase C activity |

| EP2 | Prostaglandin E2 receptor 2 | Ptger2 (gene name) | GPCR for E-series prostanoids including PGE2 and PGE3; couples primarily to Gs (cAMP-stimulatory) subfamily G proteins; not expressed significantly in mouse islets |

| EP3 | Prostaglandin E2 receptor 3 | Ptger3 (gene name) | GPCR for E-series prostanoids including PGE2 and PGE3; couples primarily to Gi (cAMP-inhibitory) subfamily G proteins |

| EP4 | Prostaglandin E2 receptor 4 | Ptger4 (gene name) | GPCR for E-series prostanoids including PGE2 and PGE3; couples primarily to Gs (cAMP-stimulatory) subfamily G proteins |

Research Design and Methods

Antibodies, Chemicals, and Reagents

Monoclonal insulin/proinsulin and biotin-conjugated antibodies were from Fitzgerald. RPMI 1640 medium was from Gibco. EPA, fatty acid–free BSA, and prostaglandin PGE2 were from Sigma-Aldrich. PGE3 and the PGE2 monoclonal ELISA kit were from Cayman Chemical. L-798,106 was from Tocris Bioscience. Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) was from Miltenyi Biotec. RNeasy Mini Kit and RNase-free DNase set were from Qiagen. High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit was from Applied Biosystems. FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master mix was from Roche.

Animals

All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital, which are both accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All animals were treated in accordance with the standards set forth by the National Institutes of Health Office of Animal Care and Use.

Male and female BTBR wild-type (WT) and Leptinob/ob (Ob) mice or male and female NOD mice were housed in temperature- and humidity-controlled environments with a 12:12-h light/dark cycle and fed pelleted mouse chow (Laboratory Animal Diet 2920; Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) and acidified water (Innovive, San Diego, CA) ad libitum.

EPA-Enriched Diet Studies

Upon weaning (3 to 4 weeks of age), male BTBR-WT and Ob mice were fed a modified AIN-93G base diet with or without 2 g/kg EPA or a standard chow diet (Envigo) (Supplementary Table 1). To limit endogenous AA and EPA production from shorter-chain n-6 and n-3 PUFAs, coconut oil replaced soybean oil as the predominant fat source (Supplementary Table 1). After 6 to 7 weeks on the diet, mice were subjected to oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTTs: 1 g glucose/kg body weight) and/or sacrificed for islet isolation, although the BTBR-Ob mice that did survive to 10 weeks of age were not subjected to OGTT and did not have recoverable islets.

NOD mice (male and female) were also started on the control or EPA-enriched diet upon weaning until 17 weeks of age. Mice were subjected to OGTTs, pancreas collection for tissue embedding and sectioning, or islet isolation for functional studies and/or gene expression analyses.

EPA Conjugation and Incubation

EPA was reconstituted to the manufacturer’s recommended concentration in 100% ethanol prior to use and conjugated to sterile filtered 10% fatty acid–free BSA in culture media for 60 min. Conjugated EPA was added to culture medium containing final ethanol and BSA concentrations of 0.1 and 1%, respectively, to minimize cell distress. Islets were then incubated for 48 h with EPA or BSA control medium prior to downstream applications.

Islet Isolation for Ex Vivo Fatty Acid Incubation and Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion Assay

Islets were isolated from 10-week-old male and 10–13-week-old female BTBR-Ob mice as previously described (9). All BTBR-Ob mice were severely diabetic (fasting blood glucose >500 mg/dL) prior to islet isolation. Glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) assays were performed as previously described (10) after the indicated treatments. Pooled islets from male and female animals were used for all in vitro experiments.

Lipid Extraction and Gas Chromatography Analysis

Prior to lipid analysis, islets were washed once with PBS and snap frozen. The samples were then vortexed vigorously in a 2:1 CHCl3/MeOH mixture with 10 mg/100 mL butylated hydroxytoluene. A Folch lipid extraction followed by thin-layer chromatography to separate lipid classes was performed as previously described (11). Gas chromatography analysis was performed as previously described (12).

IL-1β Treatment

Lyophilized IL-1β was reconstituted per the manufacturer’s recommendation. Culture media containing the indicated concentration of IL-1β, without EPA, was then added to islets for 24 h prior to further analysis.

RNA Isolation, cDNA Synthesis, and Gene Expression Analysis

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and gene expression analysis was performed as previously described (13). All gene expression was normalized to that of β-actin. Primer sequences are available upon request.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis

Media samples analyzed by mass spectrometry were collected and immediately snap frozen. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) analyses were performed by the Vanderbilt University Eicosanoid Core Laboratory.

PGE2 Analysis

Media samples were collected and immediately snap frozen prior to analysis. A PGE2 ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging of NAD(P)H

Islets were imaged on a custom-built multiphoton laser scanning system described previously in Gregg et al. (14). The islets were imaged in standard external solution (135 mmol NaCl, 4.8 mmol KCl, 5 mmol CaCl2, 1.2 mmol MgCl2, 20 mmol HEPES, and 10 mmol glucose; pH 7.35) containing BSA and with or without EPA as indicated. A custom MATLAB script was used to generate phasor histograms using the equations first described in Digman et al. (15).

Quantification of NOD Islet Immune Infiltration

NOD mouse pancreata were collected at the end of the feeding study and fixed for frozen sections as previously described (13). The 10-μm serial sections were cut on positively charged slides, with 18 sections per stop position (3 per slide) and 3 stop positions per pancreas separated by at least 200 μm. Following hematoxylin and eosin staining, quantification of immune infiltration was accomplished using a numerical scoring system, ranking the extent of immune infiltration from no immune cells present (score of 0) to an islet that was completely infiltrated with immune cells (score of 4). Every islet in each section was scored, and the scores for each section averaged with those of the other two to yield one biological replicate.

Statistical Analysis

Data are displayed as means ± SEM unless noted otherwise. Statistical significance was determined by a t test or one- or two-way ANOVA as specified in each figure legend (Prism version 6; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was determined as P < 0.05.

Results

BTBR-WT and BTBR-Ob Islet Phospholipid AA and EPA Content Is Reflective of Diet and Can Be Altered Ex Vivo

Studies exploring dietary interventions to alter plasma membrane PUFA composition have predominantly been performed in rapidly replicating cell types (16,17). To our knowledge, no studies have explored whether a high n-3 PUFA diet alters the phospholipid composition of islets. First, we confirmed no significant differences in membrane phospholipid AA or EPA abundance between islets isolated from chow-fed BTBR-WT and BTBR-Ob animals (Fig. 1A). The ratio of islet AA and EPA between the genotypes was nearly identical (Fig. 1B). A detailed phospholipid fatty acid analysis showed no differences in any other fatty acids save a small yet statistically significant difference in the concentration of stearic acid (18:0) (Table 2, left columns).

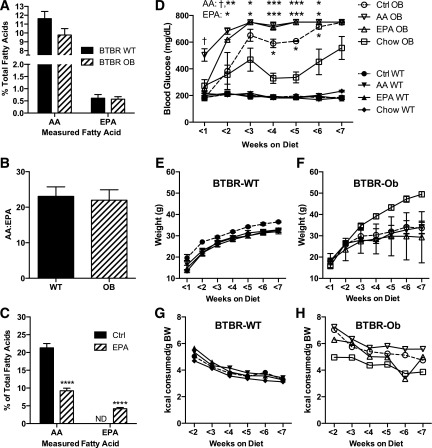

Figure 1.

Islet phospholipid AA and EPA contents are reflective of diet and can be changed in vivo. Islets were isolated from 10-week-old BTBR-WT and BTBR-Ob mice and subjected to lipid extraction followed by thin-layer chromatography to isolate the phospholipid fraction for fatty acids species determination by gas chromatography. AA and EPA are displayed as a percent of total fatty acids (A) or the ratio between the two (B). Data were compared by unpaired t test within each species (n = 11–15). C: Fatty acid analysis as described above was performed with islets from BTBR-WT mice fed a chemically defined control (Ctrl) or EPA-enriched diet for 6 weeks after weaning. N = 5–7; ****P < 0.0001. D–H: BTBR-WT and BTBR-Ob mice were fed a chow diet or an AIN-93g–based control, EPA-enriched, or AA-enriched diet for 6 weeks upon weaning. Random-fed blood glucose (D), weight (E and F), and food intake (G and H) were measured weekly starting the Monday after the diet was started (3–6 days after diet start). Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with a Tukey posttest (n = 2–6). ND, not detected. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared with Chow OB; †P < 0.05 compared with Ctrl OB.

Table 2.

Phospholipid composition of BTBR mouse islets fed a standard chow diet (left columns) and incubated with BSA (control)– or EPA-enriched media (right columns)

| FA species | BTBR-WT | BTBR-Ob | WT + BSA | WT + EPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16:0 | 27.83 ± 1.27 | 27.81 ± 1.35 | 39.23 ± 0.82 | 39.74 ± 0.70 |

| 16:1 (n-7) | 1.42 ± 0.26 | 1.58 ± 0.13 | 2.67 ± 0.43 | 2.53 ± 0.40 |

| 18:0 | 22.97 ± 0.72 | 25.66 ± 0.08* | 24.32 ± 1.02 | 22.97 ± 1.22 |

| 18:1 (n-9) | 8.90 ± 0.62 | 6.95 ± 0.93 | 7.17 ± 0.18 | 7.76 ± 1.27 |

| 18:1 (n-7) | 2.63 ± 0.62 | 2.67 ± 0.15 | 3.53 ± 0.53 | 2.95 ± 0.38 |

| 18:2 (n-6) | 6.92 ± 0.59 | 6.01 ± 0.40 | 2.15 ± 0.25 | 2.12 ± 0.20 |

| 18:3 (n-6) | 1.52 ± 0.17 | 1.53 ± 0.16 | 2.37 ± 0.22 | 2.41 ± 0.05 |

| 18:3 (n-3) | 8.34 ± 0.98 | 10.02 ± 0.92 | 9.81 ± 1.37 | 11.47 ± 1.27 |

| 20:0 | 0.90 ± 0.28 | 0.74 ± 0.21 | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 0.42 ± 0.05 |

| 20:1 (n-9) | 0.66 ± 0.11 | 0.53 ± 0.12 | 0.77 ± 0.06 | 0.69 ± 0.05 |

| 20:3 (n-6) | 1.34 ± 0.05 | 1.24 ± 0.04 | 1.16 ± 0.35 | 0.55 ± 0.06 |

| 20:4 (n-6) | 11.62 ± 0.81 | 9.77 ± 0.73 | 4.63 ± 0.44 | 3.58 ± 0.33 |

| 20:5 (n-3) | 0.61 ± 0.15 | 0.57 ± 0.10 | 0.10 ± 0.07 | 1.00 ± 0.12* |

| 22:0 | 0.85 ± 0.09 | 1.17 ± 0.24 | 1.36 ± 0.30 | 1.20 ± 0.07 |

| 22:1 (n-9) | 0.93 ± 0.16 | 0.90 ± 0.14 | 0.80 ± 0.13 | 0.89 ± 0.13 |

| 22:6 (n-3) | 4.60 ± 0.30 | 4.59 ± 0.39 | 1.45 ± 0.21 | 1.06 ± 0.14 |

Data shown as percentage of total fatty acids (FAs) ± SEM. Data were compared among treatment groups by unpaired t test (n = 11–15 for left two columns and n = 5–7 for right two columns).

*P < 0.05.

We could not detect any AA or EPA in the chow diet itself (Supplementary Table 2, left column). Therefore, in vivo elongation and desaturation of linoleic acid (18:2 [n-6]) and α-linoleic acid (18:3 [n-3]) are the sole sources of AA and EPA for mice fed the chow diet. We next synthesized a chemically defined diet devoid of AA and only essential amounts of linoleic acid (LA) and α-LA (ALA), with or without the addition of EPA at a concentration of 2 g/kg diet. Fatty acid analysis of diet samples confirmed significant EPA enrichment in the EPA diet as compared with both chow and control (Supplementary Table 2). After 6 weeks of EPA-enriched diet feeding upon weaning, islets isolated from BTBR-WT mice had 50% lower phospholipid AA as compared with islets from mice fed the control diet (Fig. 1C). Moreover, EPA-enriched diet feeding increased islet phospholipid EPA to 5% from undetectable in islets from control-fed animals (Fig. 1C). There were no significant differences in other measured fatty acids (Supplementary Table 3).

Next, we performed a dietary intervention study with BTBR-WT and BTBR-Ob mice fed chow or our chemically defined diets, recording random-fed blood glucose measurements weekly. In BTBR-WT mice, there was no effect of either diet on glycemia, weight gain, food intake (Fig. 1D, E, and G; closed symbols), or glucose tolerance (Supplementary Fig. 1). In BTBR-Ob mice, the chemically defined base diet itself, along with the EPA-supplemented diet, accelerated the development of hyperglycemia (Fig. 1D, open symbols). Interestingly, enriching the diet with AA instead of EPA further accelerated the hyperglycemic phenotype (Fig. 1D, open upside-down triangles). This accelerated diabetes development in all three chemically defined diet groups is also evident in their wasting (i.e., a failure to gain weight even in the face of a higher mean food intake) (Fig. 1F and H). Substituting amylose for dextrose or corn oil for coconut oil did not ameliorate the diabetogenic phenotype (data not shown). Because of their extreme and early hyperglycemia, glucose tolerance tests were not performed on the BTBR-Ob mice, and islets could not be isolated for analysis. We believe the switch to a chemically defined diet induces an environmental change that the BTBR-Ob mice are particularly susceptible to, but we cannot confirm this at this point.

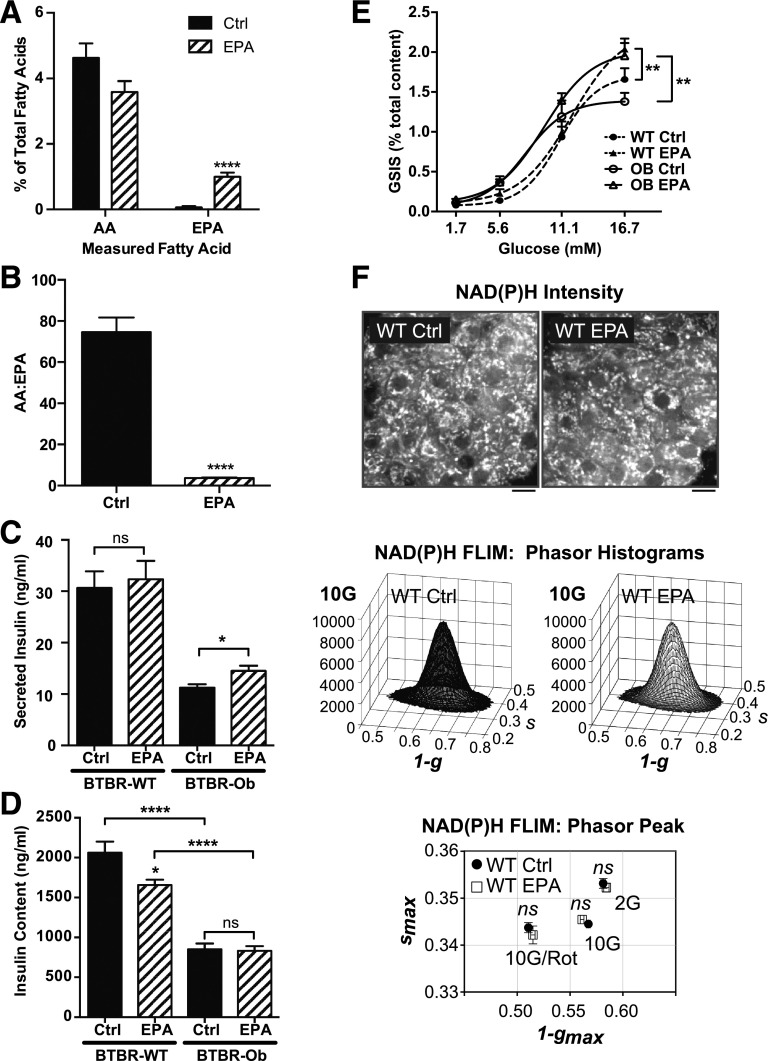

To determine if we could achieve similar changes in islet phospholipid content ex vivo, we incubated islets isolated from BTBR-WT mice with BSA control or BSA-conjugated EPA medium for 48 h. Like islets from mice fed standard chow (Fig. 1A) or the chemically defined control diet (Fig. 1C), isolated islets cultured in control medium showed high phospholipid AA content as compared with EPA (Fig. 2A, black bars), correlating with a phospholipid AA/EPA ratio of >70 (Fig. 2B, black bar). With EPA treatment, though, islet phospholipid AA was reduced and EPA increased (Fig. 2A, striped bars), resulting in a 20-fold decrease in the AA/EPA ratio (Fig. 2B, striped bar). There were no significant differences in other measured fatty acids (Table 2, right columns).

Figure 2.

Islet phospholipid AA and EPA composition can be altered ex vivo and impacts the GSIS response. A and B: Islets were incubated with BSA control (Ctrl) or 100 μmol/L EPA medium for 48 h before lipid extraction. AA and EPA are displayed as a percentage of total fatty acids (A) or the ratio between the two (B). Data were compared by unpaired t test within each species (n = 5–7). ****P < 0.0001. C: GSIS response of BTBR-WT or BTBR-Ob islets incubated with Ctrl or EPA medium. Data are represented as secreted insulin as a percentage of total content and compared by two-way ANOVA followed by a Sidak test post hoc (n = 4–6). *P < 0.05. D: Total islet insulin content from BTBR-WT and Ob islets treated with Ctrl or EPA-enriched medium. Data were compared by one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey test post hoc (n = 4–6). *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001. E: GSIS response of BTBR-WT or BTBR-Ob islets incubated with Ctrl or EPA medium. Data are represented as secreted insulin as a percentage of total content and compared by two-way ANOVA followed by a Sidak test post hoc (n = 4–6). **P < 0.01. F: Islets isolated from BTBR-WT mice were incubated with BSA control or EPA-enriched medium for 48 h followed by multiphoton NAD(P)H-FLIM analysis. Representative intensity images are displayed above phasor histograms showing the frequency distribution of NAD(P)H lifetimes. Scale bars, 5 μm. The phasor histogram peaks (1 − gmax, smax) were plotted for control and EPA-treated islets in the presence of 2 mmol/L glucose (2G), 10 mmol/L glucose (10G), and 10 mmol/L glucose plus 5 μmol/L rotenone to inhibit Complex I (10G/Rot). Data were compared by one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey test post hoc (n = 30–41 islets per condition from 4 animals each).

EPA Phospholipid Enrichment Enhances GSIS in Both BTBR-WT and BTBR-Ob Islets Ex Vivo

Fatty acids, including EPA, have been reported to have both detrimental and beneficial effects on islet function, in part depending on whether they are given acutely or chronically (2,18–20). To determine whether chronic EPA treatment influences islet function, we performed GSIS assays using islets isolated from BTBR-WT or BTBR-Ob mice incubated with control or EPA-enriched media. EPA treatment did not affect the total insulin secreted from BTBR-WT islets, but did increase the total insulin secreted from BTBR-Ob islets by 30% (Fig. 2C). EPA treatment reduced total insulin content of BTBR-WT islets by 20%, while having no effect on total insulin content of BTBR-Ob islets (Fig. 2D).

When secreted insulin is normalized to total insulin content to give GSIS (expressed as percentage), islets isolated from BTBR-Ob mice showed a 20% decrease in 16.7 mmol/L GSIS as compared with islets isolated from BTBR-WT mice, confirming our previous results (3) (Fig. 2E, open vs. filled circles). EPA enrichment increased 16.7 mmol/L GSIS from both WT and BTBR-Ob islets, with islets from BTBR-WT mice showing a 27% increase in GSIS (Fig. 2E, filled triangles vs. filled circles) and islets from BTBR-Ob mice showing a 50% increase in GSIS (Fig. 2E, open triangles vs. open circles), restoring their responsiveness to that of BTBR-WT control islets. Of note, the 16.7 mmol/L GSIS response in BTBR-Ob islets treated with EPA was statistically indistinguishable from that achieved with the specific EP3 antagonist L798,106 (EPA: 1.95 ± 0.16% total content vs. L798,106: 1.86 ± 0.30% total content; N = 3; P = 0.77). EPA enrichment did not affect the half-maximal effective concentration for GSIS, which was right-shifted in both of the BTBR-Ob groups (Fig. 2E, dashed lines vs. solid lines). The increased threshold for GSIS and decreased insulin content (Fig. 2D) of the BTBR-Ob islets are consistent with their isolation from a severely diabetic mouse model.

EPA enrichment decreased the insulin content of BTBR-WT islets; thus, increased GSIS in nondiabetic islets might be a compensatory response to decreased content, or it could represent a switch in cellular fuel usage because of increased fatty acid availability. To exclude the possibility that EPA exerts its stimulatory effect by enhancing mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid cycle or electron transport chain function, NAD(P)H fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM) (14) was performed on control and EPA-enriched BTBR-WT islets at low (2 mmol/L) and high (10 mmol/L) glucose (Fig. 2F). NADH consumption by the mitochondrial respiratory chain was assessed by the further application of rotenone (5 μmol/L, complex I inhibitor). The discrete lifetimes of NADH and NADPH calculated from each image pixel were plotted as phasor histograms (i.e., frequency distributions) such that each mixture of lifetimes occupies a unique position in 1-g and s space. The lack of any EPA-induced changes in coenzyme binding to protein, which would otherwise move the phasor histogram on the 1-g and s-axes, indicates that EPA acts to enhance secretion at a site distal to the mitochondria, consistent with an enhancement of the insulin exocytosis process itself.

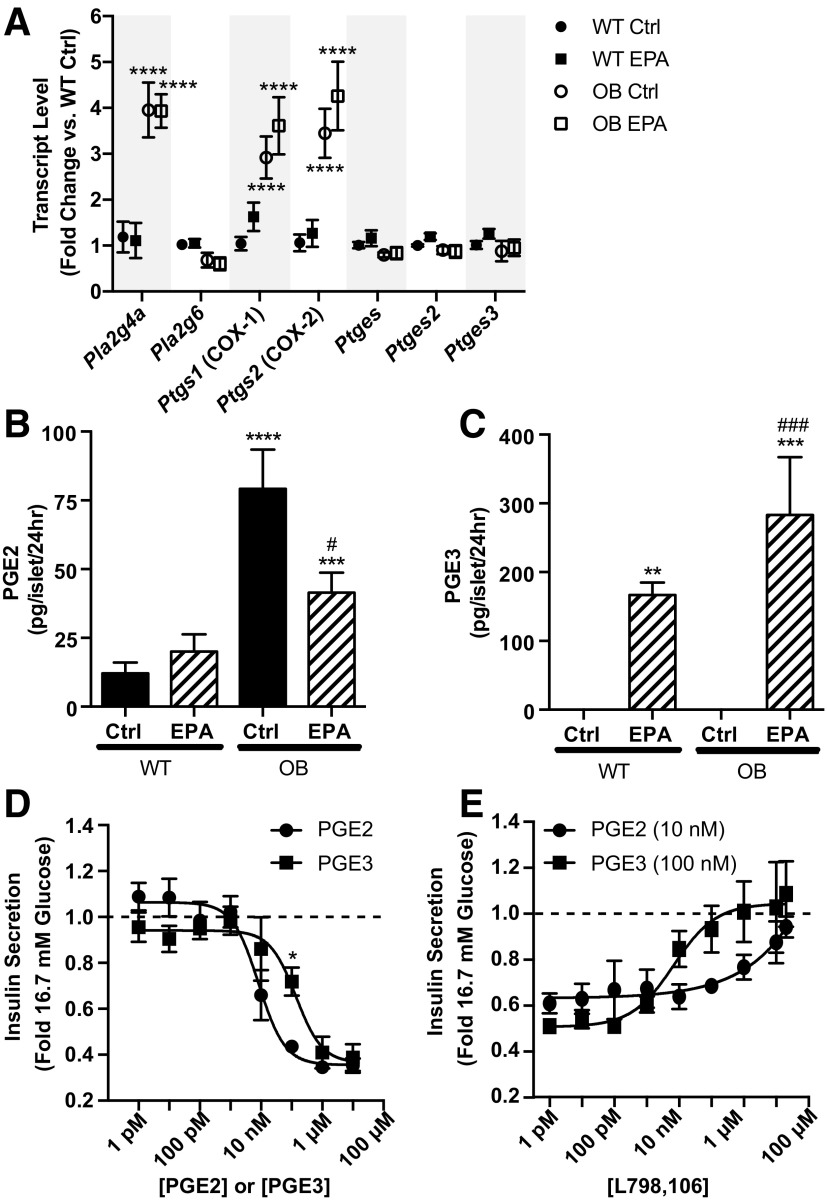

PGE2 and PGE3 Production Is Altered in EPA-Treated BTBR-Ob Islets

The predominant cyclooxygenase (COX) isoform in the β-cell is COX-2, which we previously demonstrated was upregulated in BTBR-Ob mouse islets versus BTBR-WT (3). We aimed to determine the effect of EPA enrichment on COX-2 and other PGE synthetic enzymes, including phospholipase A2 (Pla2), which cleaves AA from plasma membrane phospholipids, and PGE synthase (Ptges), which converts PGH2 into PGE2. Similar to our previously published results, COX-2 mRNA expression (gene name: Ptgs2) is upregulated 3.5-fold in BTBR-Ob islets as compared with BTBR-WT (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, COX-1 mRNA expression (gene name: Ptgs1) is increased three- to fourfold, and Pla2g4a expression, a phospholipase gene that has been linked to T2D (21), is increased fourfold (Fig. 3A). The expression of Pla2g6, Ptges, Ptges2, and Ptges3 was unchanged by genotype (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

PGE2 production is reduced and PGE3 is increased in BTBR-Ob islets treated with EPA. A: BTBR-WT and BTBR-Ob islets were incubated with BSA control (Ctrl) or EPA-enriched medium for 48 h, and islets were then snap frozen for gene expression analysis. Data were compared by one-way ANOVA with a Tukey posttest (n = 4 to 5). ****P < 0.0001 compared with BTBR-WT Ctrl. B and C: BTBR-WT and BTBR-Ob islets were incubated as above, medium collected and snap frozen, and prostaglandin analysis was performed by mass spectrometry. PGE2 and PGE3 concentrations were normalized to the number of islets for each treatment. Data were compared by one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey posttest (n = 4–6). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared with BTBR-WT Ctrl; #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 compared with BTBR-Ob Ctrl. D: Isolated BTBR-Ob islets were stimulated with increasing concentrations of PGE2 or PGE3 for 45 min. Data are represented as a fold change to maximal stimulation at 16.7 mmol/L glucose. Dose-response curves were compared by a two-way ANOVA followed by a Sidak test post hoc. N = 4 to 5; *P < 0.05. E: Isolated BTBR-Ob islets were stimulated with increasing concentrations of the competitive EP3 antagonist L798,106 in the presence of the approximate IC50 for PGE2 (10 nmol/L) or PGE3 (100 nmol/L). Data are shown as a fold change to maximal stimulation by 16.7 mmol/L glucose (n = 3).

Consistent with our previous findings (3), cultured BTBR-Ob islets produced about 650% more PGE2 than BTBR-WT islets (Fig. 3B, black bars). EPA enrichment of islets from BTBR-WT mice did not change PGE2 production (Fig. 3B, left). However, EPA enrichment of BTBR-Ob islets reduced PGE2 production by 50%, to a level similar to EPA-treated WT islets (Fig. 3B, striped bars). Moreover, EPA enrichment increased PGE3 production from both BTBR-WT and BTBR-Ob islets as compared with control-treated islets, which had undetectable PGE3 production (Fig. 3C). Like PGE2 production, BTBR-Ob islets had the highest PGE3 production. Overall, these results confirm our hypothesis that enriching islet phospholipids with EPA, thus reducing AA, shifts prostaglandin production to favor PGE3 as opposed to PGE2.

PGE3 Has a Weaker Inhibitory Effect on BTBR-Ob Islet GSIS Than PGE2

We hypothesized that altering the PGE2/PGE3 ratio might be at least partially responsible for the protective effect of EPA on GSIS from BTBR-Ob islets. Similar to our previous results with PGE1 (3), neither PGE2 nor PGE3 affected the GSIS response from BTBR-WT islets (Supplementary Fig. 2). However, PGE2 and PGE3 both reduced the GSIS response from BTBR-Ob islets in a dose-dependent manner, but the IC50 for reducing GSIS was ∼10-fold weaker for PGE3 as compared with PGE2 (Fig. 3D), a difference that was statistically significant (13.8 ± 6.5 vs. 171.7 ± 61.5 nmol/L; P < 0.05). Moreover, the effects of both PGE2 and PGE3 could be fully competed by increasing concentrations of the specific EP3 antagonist L798,106 (Fig. 3E).

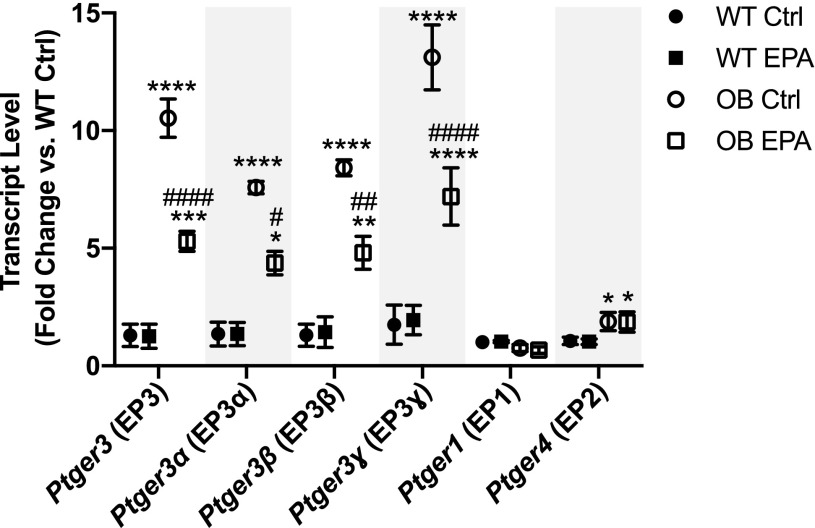

EPA Reduces EP3 Gene Expression but Not That of Other EP Receptor Family Members

Next, we asked whether enriching BTBR-Ob islet phospholipids with EPA would influence EP3 receptor mRNA expression (gene name: Ptger3), the other aspect of PGE2 signaling that is upregulated in diabetic islet. Similar to our previous results (3), we show a >10-fold increase in Ptger3 expression in BTBR-Ob islets as compared with BTBR-WT islets (Fig. 4, open circles). However, EPA enrichment reduced this enhanced Ptger3 expression by approximately fivefold, whether assayed as total mRNA or at the splice variant level (Fig. 4, α, β, and ɣ). The other EP receptors that are expressed in BTBR-Ob islets are EP1 (gene name: Ptger1) and EP4 (gene name: Ptger4) (3). We confirm a twofold increase in EP4 but not EP1 gene expression in BTBR-Ob islets as compared with BTBR-WT (3), levels that were unchanged with EPA treatment (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

EPA reduces EP3 mRNA expression in BTBR-Ob islets. BTBR-WT and Ob islets were incubated with BSA control (Ctrl) or EPA-enriched medium for 48 h, and islets were then snap frozen for gene expression analysis. Data were compared by one-way ANOVA with a Tukey posttest (n = 4 to 5). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared with BTBR-WT Ctrl; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ####P < 0.001 compared with BTBR-Ob Ctrl.

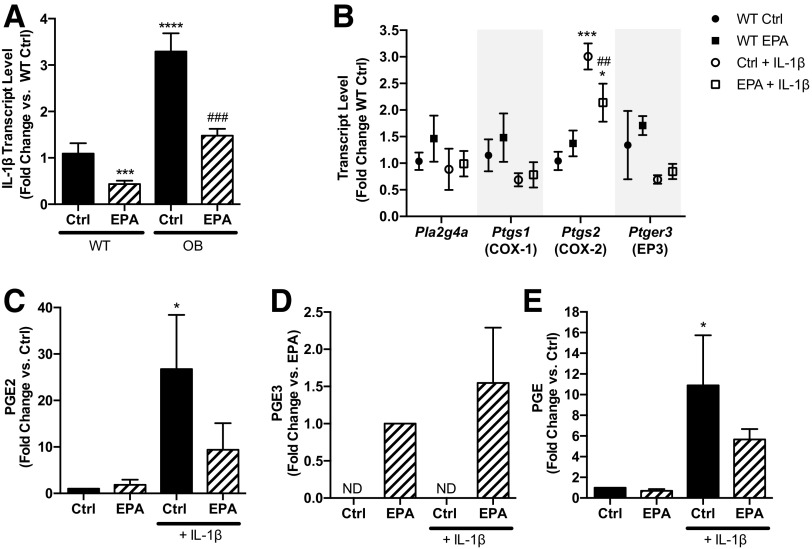

Elevated IL-1β Expression Drives Prostaglandin Production in BTBR-Ob Islets

Treatment with the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β has been shown to upregulate islet COX-2 and EP3 expression and/or PGE2 production itself, effects that are reduced by the COX inhibitor sodium salicylate (8,22). We aimed to determine the relevance of IL-1β to the BTBR-Ob model, as well as any impact of EPA enrichment. We found that IL-1β mRNA expression is threefold higher in BTBR-Ob islets as compared with BTBR-WT (Fig. 5A, black bars). Furthermore, EPA treatment reduces IL-1β mRNA expression from both BTBR-WT and BTBR-Ob islets, the latter by more than twofold (Fig. 5A, striped bars).

Figure 5.

IL-1β expression is correlated with Ptgs2 expression and PGE2 production in BTBR-Ob islets and can promote PGE2/PGE3 production from BTBR-WT islets. A: BTBR-WT and BTBR-Ob islets were incubated with BSA control (Ctrl) or 100 μmol/L EPA for 48 h, and islets were then snap frozen for gene expression analysis. Data were compared by one-way ANOVA with a Tukey posttest. N = 4 to 5; ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 compared with BTBR-WT Ctrl; ###P < 0.001 compared with BTBR-Ob Ctrl. B–E: BTBR-WT islets were incubated with BSA control or 100 μmol/L EPA for 48 h and then fresh medium containing 10 ng/mL IL-1β for 24 h. Islets were then snap frozen for gene expression analysis (B), and data were compared by one-way ANOVA with a Tukey posttest (n = 4). ND, not detected. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 compared with WT Ctrl; ##P < 0.01 compared with Ctrl + IL-1β. Islet media was collected, snap frozen, and prostaglandin analysis was performed by LC/MS/MS (C and D) or ELISA (E). Data were compared by one-way ANOVA with a Dunnett posttest. N = 3 to 4. *P < 0.05 compared with BTBR-WT Ctrl.

To determine if the upregulation of IL-1β is sufficient to increase PGE2 production and signaling in islets isolated from nondiabetic mice, we incubated BTBR-WT islets in control or EPA-enriched medium for 48 h and then changed the islets to fresh medium containing 10 ng/mL IL-1β for 24 h. We assayed the subset of prostaglandin production and signaling genes for which expression was significantly different between BTBR-WT and BTBR-Ob islets (Figs. 3 and 4) and found a threefold increase in COX-2 mRNA with IL-1β treatment (Fig. 5B). This effect was partially ameliorated by EPA enrichment, reducing COX-2 mRNA expression to only 1.5-fold that observed in control islets. The elevation in COX-2 mRNA expression corresponded with increased PGE2 production that was also partially reduced by EPA enrichment (Fig. 5C). PGE3 was undetectable in islet samples that were not enriched with EPA, and the IL-1β–treated group had the highest mean PGE3 production, although this was not statistically different from EPA-enriched control islets (Fig. 5D).

The data shown in Fig. 5C and D are displayed as fold change versus control because of variation in absolute quantification of PGE2 or PGE3 across the four experimental replicates. To ensure that this variation was not the result of differences in recovery after extraction for LC/MS/MS, we measured PGE from unextracted medium using a PGE2 ELISA kit that has 43% cross-reactivity with PGE3 (Prostaglandin E2 ELISA Kit, Monoclonal; Cayman Chemical) and obtained very similar results (Fig. 5E). These results suggest that although different BTBR-WT islet preparations may have different baseline capacities for PGE production after 3 days of culture, IL-1β alone promotes COX-2 mRNA expression and enriches downstream PGE production, whereas another factor in the diabetic condition may be required for upregulation of other enzymes in the PGE2/PGE3 synthetic and signaling pathways.

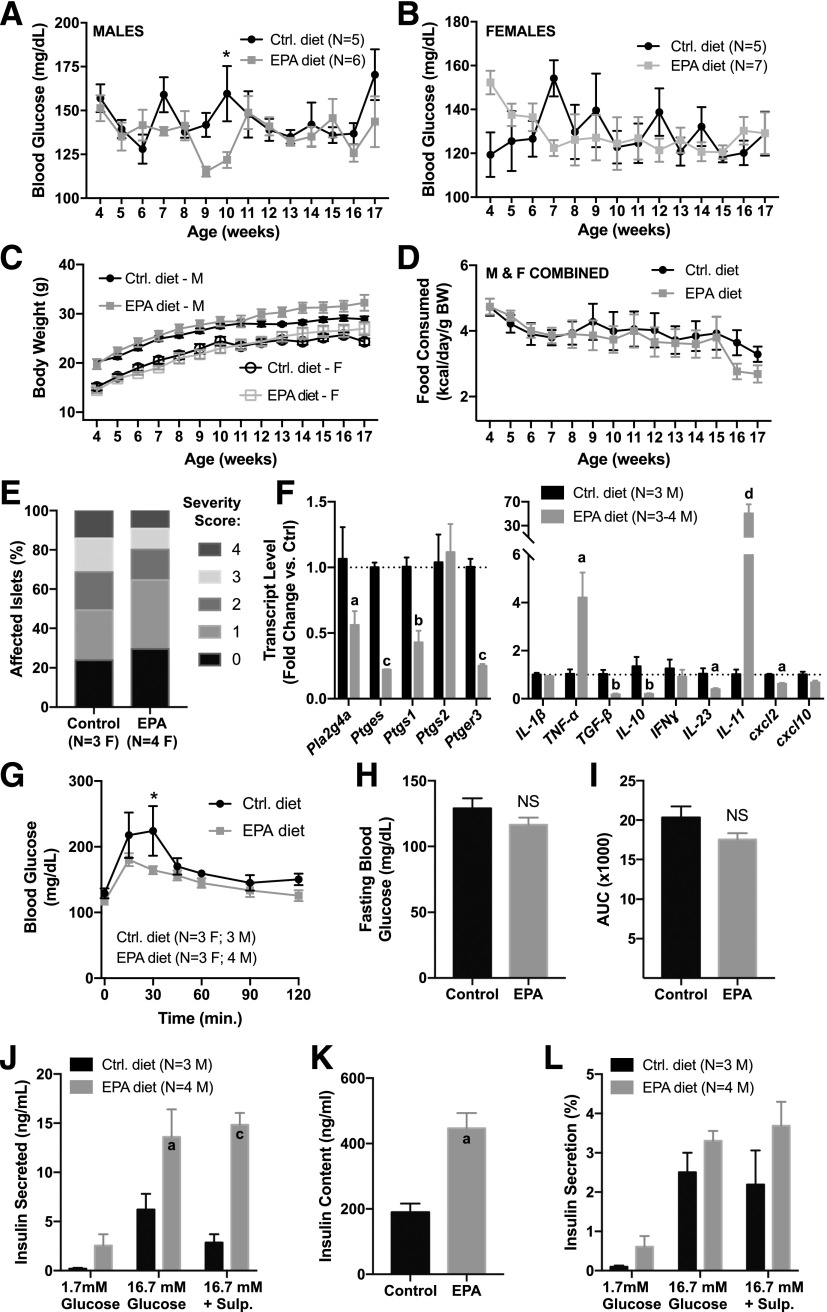

Finally, we aimed to determine the effect of dietary EPA enrichment in a different mouse model of diabetes that incorporates a strong immune phenotype: the NOD mouse. We used both male (N = 11) and female mice (N = 13), and subjected them to control or EPA-enriched diet feeding from weaning (3 to 4 weeks of age) until 17 weeks of age, a time period during which NOD mice have been reported to develop β-cell failure and overt hyperglycemia (23). Only one female mouse developed hyperglycemia during this timeframe, though (from the EPA-enriched diet group); therefore, we restricted our analysis to the nondiabetic mice.

Random-fed blood glucose levels (Fig. 6A and B) were not significantly different between the diet groups, save for at 10 weeks of age in the male cohort (Fig. 6A). Similarly, body weights (Fig. 6C) and food intake (Fig. 6D) did not differ between the groups (as mice were not singly housed, food consumption was determined by dividing the mass of food eaten per day by the number of mice in the cage and then data from males and females combined to increase the power).

Figure 6.

A diet enriched in EPA improves glucose tolerance, gene expression profiles, and islet function in the NOD mouse. Male (M) and female (F) NOD mice were fed a diet enriched in EPA or a defined control diet from weaning until 17 weeks of age, and random-fed blood glucose (A and B), body weight (C), and food consumption (D) recorded weekly. Data were compared by two-way ANOVA with Sidak test post hoc. *P < 0.05. E: Pancreas sections from 17-week-old female NOD mice fed the control or EPA-enriched diet were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and analyzed to determine the percentage of islets in each of the islet inflammation scoring categories, in which 0 is no infiltration and 4 is completely infiltrated. F: Quantitative RT-PCR results for genes involved in prostaglandin production and signaling (left) and cytokines (right) in islets isolated from 17-week-old male NOD mice fed the control (Ctrl) or EPA-enriched diet. Fold change in gene expression was calculated using 2ΔΔCt, in which each biological replicate is normalized to the mean threshold cycle (Ct) value for β-actin. Significance was calculated for each gene using Student t test. aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01, cP < 0.001, dP < 0.0001 vs. control. G–I: Seventeen-week-old male and female mice were subjected to OGTT to 1 g/kg glucose. Glucose excursions (G), fasting blood glucose (H), and area under the curve (AUC; I) were recorded for each group. Data were compared by two-way ANOVA with Sidak test post hoc (G) or Student t test (H and I). *P < 0.05. Islets isolated from 17-week-old male NOD mice fed the control or EPA-enriched diet were subjected to in vitro analysis for total insulin secretion (J), insulin content (K), and insulin secreted as a percentage of total islet insulin content (L). Sulp., sulprostone. Significance was calculated by two-way ANOVA with Sidak test post hoc. aP < 0.05, cP < 0.001 vs. the appropriate control.

Nondiabetic NOD mice still display islet immune infiltration and β-cell dysfunction (23). Therefore, we quantified the extent of islet immune infiltration by hematoxylin and eosin staining of pancreas sections and found a similar infiltration profile between the control and EPA-enriched diet groups, although the EPA-enriched diet group did have higher percentages of islets that were noninfiltrated (score of 0) or showed peri-islet immune cells only (score of 1). The mean immune infiltration scores were not significantly different between the groups, although that of mice from the EPA-enriched diet did trend lower (control diet: 1.73 ± 0.22; EPA diet: 1.35 ± 0.30; N = 3 to 4/group; P = 0.38). Next, we looked at the expression of PGE2 synthetic and signaling genes and pro/anti-inflammatory cytokines and found significant differences between islets isolated from mice fed the EPA-enriched diet as compared with the control diet. Islets from mice fed the EPA-enriched diet had significantly lower Pla2g4a, Ptges, Ptgs1, and Ptger3 expression as compared with mice fed the control diet (Fig. 6F, left). Additionally, although most of the cytokine genes assayed had reduced expression in islets from mice fed the EPA-enriched diet, expression of tumor necrosis factor-α and IL-11 was significantly increased (Fig. 6F, right).

Next, we aimed to determine the impact of the EPA-enriched diet on islet function. First, we performed OGTTs and found lower mean blood glucose levels 15 and 30 min after glucose administration in mice fed the EPA-enriched diet as compared with the control diet, with the difference at 30 min being statistically significant (Fig. 6G). Further analysis of the individual glucose excursions showed that mean fasting blood glucose and area under the curve were reduced in the EPA-fed mice, although neither was statistically significant (Fig. 6H and I, respectively).

Decreased peak blood glucose levels (Fig. 6G), coupled with changes in the expression of PGE2 production and signaling genes (Fig. 6F), suggested a primary effect of EPA-enriched diet feeding on β-cell function. To test this directly, we isolated islets and performed GSIS assays ex vivo, with or without the addition of the selective EP3 agonist sulprostone. Islets from mice fed the EPA-enriched diet secreted significantly more insulin in response to glucose than islets from mice fed the control diet and showed no inhibitory response to sulprostone (Fig. 6J). This increased secretion seemed primarily to be because of significantly increased islet insulin content (Fig. 6K), as normalizing the secreted insulin to the total insulin content negated the statistically significant differences between the EPA diet and control diet groups, although those from animals fed the EPA-enriched diet still had higher mean GSIS in all cases (Fig. 6L).

Discussion

PGE2 is the most abundant prostaglandin formed in β-cells and has been linked with decreased β-cell function, particularly in the condition of diabetes or in response to proinflammatory cytokines (3,6,7,24,25). A number of methods to target the PGE2 production and signaling pathway have been proposed as antidiabetic therapies. We ourselves have shown that a competitive EP3 antagonist, L798,106, augments the GSIS response of islets isolated from diabetic mice and human organ donors with diabetes (3). Yet, the in vivo efficacy of L798,106, or any other specific EP3 antagonist, is unclear.

In the β-cell, Ptgs2 (also known as COX-2) is the predominant COX isoform (25), but specifically targeting this isoform to reduce metabolite production is limited by the cardiovascular risks of selective COX-2 inhibitors. Recent randomized controlled trials of various nonselective COX inhibitors have shown promise in reducing fasting blood glucose and HbA1c (26). Even so, these drugs are not without side effects, and the relevance to improved morbidity and mortality remains unclear (26). This does not dampen potential enthusiasm for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as antidiabetic agents or adjuvant therapies, but leaves open the possibility for other methods to target the diabetic β-cell.

Other researchers have explored modification of substrate availability as a means to reduce n-6 PUFA metabolite production. The fat-1 mouse expresses a Caenorhabditis elegans desaturase enzyme that converts all n-6 PUFAs to n-3 PUFAs, dramatically reducing the total n-6 to n-3 ratios in all tissues tested (27). These mice show a 98% decrease in the total pancreatic n-6/n-3 (28). The mfat-1 mouse uses the same transgene as the fat-1 mouse, except that the codons are optimized for the mammalian translation machinery (29). As compared with WT controls, mfat-1 islets have a 92% lower n-6/n-3, 46% lower PGE2 production, and 60% higher GSIS response (29). These results fit well with our observations from EPA-incubated BTBR-Ob islets, with a 96% decrease in AA/EPA (Fig. 2B), a 50% decrease in PGE2 production (Fig. 3B), and a 50% increase in GSIS as compared with control-treated islets (Fig. 2E). The better comparison with the strain used by Pan et al. (30) (C57Bl/6J), though, would be BTBR-WT, and we saw no decrease in PGE2 production when BTBR-WT islets were incubated with EPA and only a 20% increase in GSIS (Figs. 3B and 2E, respectively). We also observed a 20% decrease in islet insulin content (Fig. 2D), whereas Wei et al. (29) observed no effect of mfat-1 transgene expression on islet insulin content, meaning that the insulin secreted into the medium from BTBR-WT islets treated or not with EPA was essentially identical, similar to Wang et al. (31), who showed that islets isolated from fat-1 mice had the same GSIS response as littermate controls. We cannot explain the differences between the mfat-1 islet results and our own.

Fat-1 mice are protected from developing hyperglycemia when subjected to multiple low-dose streptozotocin induction of diabetes (28,31), which is known to stimulate an immune response (32). IL-1β has been proposed as a critical regulator of islet Ptgs2 expression (8,22,33,34). IL-1β can also induce rat islet Ptger3 expression (8). In our study, IL-1β, Ptgs2, and Ptger3 expression are all significantly enhanced in BTBR-Ob islets as compared with BTBR-WT, and EPA enrichment significantly reduces the expression of IL-1β and Ptger3 (Figs. 3A, 4, and 5A). Further, IL-1β is sufficient to increase Ptgs2 expression and downstream PGE2 production from BRBR-WT islets, and EPA enrichment significantly blunts these effects (Fig. 5B). Yet, this model is complicated by the fact that EPA enrichment had no effect on BTBR-Ob islet Ptgs2 mRNA expression (Fig. 3A) and suggests that other factors may be helping to limit PGE2 production and action with EPA treatment.

Previous binding and functional studies with a human EP3 receptor showed higher IC50 and lower relative affinity for PGE3 versus PGE2 (35,36). Our results with isolated mouse islets support these conclusions, as ∼10 times more PGE3 is required to inhibit insulin secretion to the same extent as PGE2 (Fig. 3D). Yet, little is known regarding the direct impact of other EPA-derived eicosanoids on β-cell function. One EPA-derived eicosanoid, 5-hydroxy-EPA, can agonize GPR119 in a mouse insulinoma cell line, which ultimately enhances insulin secretion (37). Moreover, resolution of an immune response leads to the formation of EPA-derived metabolites termed resolvins, which promote insulin sensitivity in an obese mouse model (38). In the current study, we cannot rule out other EPA-derived eicosanoids and metabolites influencing insulin secretion in islets from BTBR-Ob mice.

Long-chain fatty acids, including EPA, can directly mediate signaling pathways potentially impacting β-cell function and health depending on whether they are transiently or chronically administered (2,39). Transient EPA treatment augmented insulin secretion from the β-TC3 insulinoma cell line (40). In another study, 48-h EPA treatment restored palmitate-treated mouse islet insulin secretion by inhibiting the activation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c), and diabetic mice provided a daily dose of EPA for 28 days exhibited lower SREBP-1c mRNA levels and enhanced islet insulin secretion ex vivo (18). Taken together, we cannot rule out the impact of these other pathways on our model. Indeed, our NAD(P)H-FLIM data (Fig. 2F) rule out any effect of EPA to augment flux through the electron transport chain, suggesting that EPA acts at a distal site in the secretory pathway, which would be consistent with a model in which EPA acts directly or indirectly (by reducing PGE2 production) on β-cell function. The concordance of EPA enrichment with the effects of a specific EP3 antagonist, L798,106, on improving GSIS from BTBR-Ob islets, though, supports the latter model.

Studying an n-3 PUFA dietary intervention directly has been complicated by the fact that mice fed a high-PUFA diet do not typically become obese (41); thus, any protective effect would be complicated by the lack of obesity, insulin resistance, and accompanying metabolic derangements. We were not able to complete a full dietary intervention study in the BTBR-Ob mice because of the accelerated diabetes phenotype after feeding a chemically defined diet (Fig. 1D–H). This challenge, though, allowed us to determine the direct effect of EPA enrichment specifically on β-cell function in islets isolated from a T2D model. In addition, we were able to complete a dietary intervention study in the NOD mouse model. Although we are unable to comment on whether the EPA-enriched diet is protective overall against the development of diabetes because of a lack of diabetic phenotype penetrance, we did find improved glucose tolerance (Fig. 6G) in mice fed a diet enriched in EPA, which directly correlated with higher insulin secretion and a reduced inhibitory effect to the EP3 agonist sulprostone in islets isolated from NOD mice fed the EPA-enriched diet (Fig. 6J–L). Interestingly, some of the mechanisms implicated in the BTBR-Ob model, including increased IL-1β and Ptgs2 expression, do not appear to be recapitulated in the NOD model, at least at the 17-week time point. Further, changes in inflammatory cytokines, whether significantly decreased (transforming growth factor-β, IL-10, IL-23, and cxcl2) or increased (tumor necrosis factor-α and IL-11) (Fig. 6F, right), even in the absence of significant differences in the overall islet immune infiltration profile (Fig. 6E), suggest that improved β-cell function might also be because of changes in the type and/or cellular composition of immune infiltrate, a hypothesis that is worthy of future study.

To summarize, in this work, we find an important link between islet phospholipid composition and function in murine models of diabetes, both T1D and T2D. We demonstrate that EPA enrichment enhances T2D mouse islet function because of both reduced PGE2 production and EP3 expression and is correlated with improved glucose tolerance and islet function in a T1D mouse model. These beneficial effects result from both decreased AA substrate availability and an altered islet inflammatory profile, although the specific mechanisms for protection differ between the T2D and T1D models.

Supplementary Material

Article Information

Acknowledgments. The authors thank Dr. James Ntambi (Department of Nutritional Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison) and the laboratory members for the use of the gas chromatograph and Ginger Milne and staff at the Vanderbilt University Eicosanoid Core for dedication to this project.

Funding. This work was supported by American Diabetes Association grants 1-14-BS-115 (to M.E.K.) and 1-16-IBS-212 (to M.J.M.); National Institutes of Health grants R01-DK-102598 (to M.E.K.), K01-DK-101683 (to M.J.M.), and R21-AG-050135 (to M.J.M.); U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs grant I01-BX001880 (to D.B.D.); and startup and pilot project funding from the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health (to M.J.M. and M.E.K., respectively). J.C.N., C.R.K., and D.A.F. were supported in part by training grants from the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institute on Aging (National Institutes of Health grant T32-AG-000213). A.L.B. was supported in part by a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship from the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. D.A.F. was supported in part by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Science and Medicine Graduate Research Scholars Program.

Duality of Interest. No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author Contributions. J.C.N., M.D.S., A.L.B., R.J.F., C.R.K., D.A.F., S.M.S., H.K.B., K.M.C., and H.N.W. performed experiments and analyzed data. J.C.N., M.J.M., and M.E.K. prepared and edited the manuscript. K.W.E., M.J.M., D.B.D., and M.E.K. conceptualized the experiments. M.E.K. is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/db16-1362/-/DC1.

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the William S. Middleton Memorial Veterans Hospital in Madison, WI. The contents do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. Government.

See accompanying article, p. 1464.

References

- 1.Rizos EC, Ntzani EE, Bika E, Kostapanos MS, Elisaf MS. Association between omega-3 fatty acid supplementation and risk of major cardiovascular disease events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2012;308:1024–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Itoh Y, Kawamata Y, Harada M, et al. Free fatty acids regulate insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells through GPR40. Nature 2003;422:173–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimple ME, Keller MP, Rabaglia MR, et al. Prostaglandin E2 receptor, EP3, is induced in diabetic islets and negatively regulates glucose- and hormone-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes 2013;62:1904–1912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metz SA, Robertson RP, Fujimoto WY. Inhibition of prostaglandin E synthesis augments glucose-induced insulin secretion is cultured pancreas. Diabetes 1981;30:551–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robertson RP, Gavareski DJ, Porte D Jr, Bierman EL. Inhibition of in vivo insulin secretion by prostaglandin E1. J Clin Invest 1974;54:310–315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robertson RP, Tsai P, Little SA, Zhang HJ, Walseth TF. Receptor-mediated adenylate cyclase-coupled mechanism for PGE2 inhibition of insulin secretion in HIT cells. Diabetes 1987;36:1047–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seaquist ER, Walseth TF, Nelson DM, Robertson RP. Pertussis toxin-sensitive G protein mediation of PGE2 inhibition of cAMP metabolism and phasic glucose-induced insulin secretion in HIT cells. Diabetes 1989;38:1439–1445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran PO, Gleason CE, Robertson RP. Inhibition of interleukin-1beta-induced COX-2 and EP3 gene expression by sodium salicylate enhances pancreatic islet beta-cell function. Diabetes 2002;51:1772–1778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neuman JC, Truchan NA, Joseph JW, Kimple ME. A method for mouse pancreatic islet isolation and intracellular cAMP determination. J Vis Exp 2014;88:e50374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Truchan NA, Brar HK, Gallagher SJ, Neuman JC, Kimple ME. A single-islet microplate assay to measure mouse and human islet insulin secretion. Islets 2015;7:e1076607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flowers MT, Ade L, Strable MS, Ntambi JM. Combined deletion of SCD1 from adipose tissue and liver does not protect mice from obesity. J Lipid Res 2012;53:1646–1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miyazaki M, Kim HJ, Man WC, Ntambi JM. Oleoyl-CoA is the major de novo product of stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 gene isoform and substrate for the biosynthesis of the Harderian gland 1-alkyl-2,3-diacylglycerol. J Biol Chem 2001;276:39455–39461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brill AL, Wisinski JA, Cadena MT, et al. Synergy between Gαz deficiency and GLP-1 analog treatment in preserving functional β-cell mass in experimental diabetes. Mol Endocrinol 2016;30:543–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gregg T, Poudel C, Schmidt BA, et al. Pancreatic β-cells from mice offset age-associated mitochondrial deficiency with reduced KATP channel activity. Diabetes 2016;65:2700–2710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Digman MA, Caiolfa VR, Zamai M, Gratton E. The phasor approach to fluorescence lifetime imaging analysis. Biophys J 2008;94:L14–L16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chilton FH, Patel M, Fonteh AN, Hubbard WC, Triggiani M. Dietary n-3 fatty acid effects on neutrophil lipid composition and mediator production. Influence of duration and dosage. J Clin Invest 1993;91:115–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raphael W, Sordillo LM. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammation: the role of phospholipid biosynthesis. Int J Mol Sci 2013;14:21167–21188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kato T, Shimano H, Yamamoto T, et al. Palmitate impairs and eicosapentaenoate restores insulin secretion through regulation of SREBP-1c in pancreatic islets. Diabetes 2008;57:2382–2392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bollheimer LC, Skelly RH, Chester MW, McGarry JD, Rhodes CJ. Chronic exposure to free fatty acid reduces pancreatic beta cell insulin content by increasing basal insulin secretion that is not compensated for by a corresponding increase in proinsulin biosynthesis translation. J Clin Invest 1998;101:1094–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paolisso G, Gambardella A, Amato L, et al. Opposite effects of short- and long-term fatty acid infusion on insulin secretion in healthy subjects. Diabetologia 1995;38:1295–1299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolford JK, Konheim YL, Colligan PB, Bogardus C. Association of a F479L variant in the cytosolic phospholipase A2 gene (PLA2G4A) with decreased glucose turnover and oxidation rates in Pima Indians. Mol Genet Metab 2003;79:61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corbett JA, Kwon G, Turk J, McDaniel ML. IL-1 beta induces the coexpression of both nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase by islets of Langerhans: activation of cyclooxygenase by nitric oxide. Biochemistry 1993;32:13767–13770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park YS, Gauna AE, Cha S. Mouse models of primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Curr Pharm Des 2015;21:2350–2364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oshima H, Taketo MM, Oshima M. Destruction of pancreatic beta-cells by transgenic induction of prostaglandin E2 in the islets. J Biol Chem 2006;281:29330–29336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robertson RP. Dominance of cyclooxygenase-2 in the regulation of pancreatic islet prostaglandin synthesis. Diabetes 1998;47:1379–1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bellucci PN, González Bagnes MF, Di Girolamo G, González CD. Potential effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Pharm Pract. 18 May 2016 [Epub ahead of print]. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0897190016649551https://doi.org/10.1177/0897190016649551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang JX, Wang J, Wu L, Kang ZB. Transgenic mice: fat-1 mice convert n-6 to n-3 fatty acids. Nature 2004;427:504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bellenger J, Bellenger S, Bataille A, et al. High pancreatic n-3 fatty acids prevent STZ-induced diabetes in fat-1 mice: inflammatory pathway inhibition. Diabetes 2011;60:1090–1099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wei D, Li J, Shen M, et al. Cellular production of n-3 PUFAs and reduction of n-6-to-n-3 ratios in the pancreatic beta-cells and islets enhance insulin secretion and confer protection against cytokine-induced cell death. Diabetes 2010;59:471–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan J, Cheng L, Bi X, et al. Elevation of ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids attenuates PTEN-deficiency induced endometrial cancer development through regulation of COX-2 and PGE2 production. Sci Rep 2015;5:14958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Song MY, Bae UJ, Lim JM, Kwon KS, Park BH. n-3 Polyunsaturated fatty acids protect against pancreatic β-cell damage due to ER stress and prevent diabetes development. Mol Nutr Food Res 2015;59:1791–1802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Like AA, Rossini AA. Streptozotocin-induced pancreatic insulitis: new model of diabetes mellitus. Science 1976;193:415–417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corbett JA, McDaniel ML. Intraislet release of interleukin 1 inhibits beta cell function by inducing beta cell expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase. J Exp Med 1995;181:559–568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hughes JH, Easom RA, Wolf BA, Turk J, McDaniel ML. Interleukin 1-induced prostaglandin E2 accumulation by isolated pancreatic islets. Diabetes 1989;38:1251–1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wada M, DeLong CJ, Hong YH, et al. Enzymes and receptors of prostaglandin pathways with arachidonic acid-derived versus eicosapentaenoic acid-derived substrates and products. J Biol Chem 2007;282:22254–22266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bagga D, Wang L, Farias-Eisner R, Glaspy JA, Reddy ST. Differential effects of prostaglandin derived from omega-6 and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on COX-2 expression and IL-6 secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:1751–1756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kogure R, Toyama K, Hiyamuta S, Kojima I, Takeda S. 5-Hydroxy-eicosapentaenoic acid is an endogenous GPR119 agonist and enhances glucose-dependent insulin secretion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2011;416:58–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.González-Périz A, Horrillo R, Ferré N, et al. Obesity-induced insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis are alleviated by omega-3 fatty acids: a role for resolvins and protectins. FASEB J 2009;23:1946–1957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kotarsky K, Nilsson NE, Flodgren E, Owman C, Olde B. A human cell surface receptor activated by free fatty acids and thiazolidinedione drugs. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003;301:406–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Konard RJ, Stoller JZ, Gao ZY, Wolf BA. Eicosapentaenoic acid (C20:5) augments glucose-induced insulin secretion from beta-TC3 insulinoma cells. Pancreas 1996;13:253–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buckley JD, Howe PR. Anti-obesity effects of long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Obes Rev 2009;10:648–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.