Abstract

Purpose

Refractory pediatric leukemia remains one of the leading causes of death in children. Intensification of current chemotherapy regimens to improve the outcome in these children is often limited by the effects of drug resistance and cumulative toxicity. Hence, the search for newer agents and novel therapeutic approaches are urgently needed to formulate the next-generation early-phase clinical trials for these patients.

Materials and methods

A comprehensive library of antimicrobials, including eight HIV protease inhibitors (nelfinavir [NFV], saquinavir, indinavir, ritonavir, amprenavir, atazanavir, lopinavir, and darunavir), was tested against a panel of pediatric leukemia cells by in vitro growth inhibition studies. Detailed target modulation studies were carried out by Western blot analyses. In addition, drug synergy experiments with conventional and novel antitumor agents were completed to identify effective treatment regimens for future clinical trials.

Results

Several of the HIV protease inhibitors showed cytotoxicity at physiologically relevant concentrations (half-maximal inhibitory concentration values ranging from 1–24 µM). In particular, NFV was found to exhibit the most potent antileukemic properties across all cell lines tested. Mechanistic studies show that NFV leads to the induction of autophagy and apoptosis possibly through the induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Furthermore, interference with cell signaling pathways, including Akt and mTOR, was also noted. Finally, drug combination studies have identified agents with potential for synergy with NFV in its antileukemic activity. These include JQ1 (BET inhibitor), AT101 (Bcl-2 family inhibitor), and sunitinib (TK inhibitor).

Conclusion

Here, we show data demonstrating the potential of a previously unexplored group of drugs to address an unmet therapeutic need in pediatric oncology. The data presented provide preclinical supportive evidence and rationale for future studies of these agents for refractory leukemia in children.

Keywords: nelfinavir, HIV protease inhibitors, pediatric leukemia, endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, apoptosis

Introduction

Despite the recent advances achieved in the treatment of leukemia in children, the prognosis of relapsed and refractory disease remains dismal with more than 50% mortality rate.1–3 Acute and long-term toxicities of current chemotherapy agents often limit their further intensification, thus highlighting an urgent need for novel therapeutic approaches to develop newer, safer treatment protocols. One approach to circumvent such toxicity concerns is to consider activity in compounds with previously established clinical data and use, such as that of antimicrobials.

Employing agents from the field of infectious diseases in the fight against cancer has historical precedence, as exampled by the chemotherapeutic fludarabine, which is a fluorinated nucleotide analog of the antiviral agent vidarabine;4 or the tetracycline, doxycycline which has shown activity against breast cancer.5 Here, we bring focus to a class of antivirals – the HIV protease inhibitors (PIs) – which have activity against pediatric leukemia.

The HIV PIs were first developed in the early 1990s, beginning with saquinavir that was rationally designed to fit the HIV aspartyl protease – an enzyme for which there are no human analogs.6 First approved for use by 1995, the PIs have had over two decades of clinical use in the treatment regimens of HIV patients, including use in children.6 In HIV patients on PI-based therapy, it was noted that there was a dramatic drop in the rates of HIV-associated malignancies, unrelated to the viral loads or CD4 counts.7,8 This had led to studies that evaluated the effects of PIs in cancer therapy.9–11 Some of the earlier studies included murine xenograft models of Kaposi’s sarcoma, whereby Sgadari and colleagues demonstrated several PIs had effects on tumor growth, invasion, angiogenesis, and survival.10,11 Ikezoe et al pursued the PIs’ application to multiple myeloma, demonstrating effects on cell cycle arrest and STAT3 and ERK signaling.12 By the early 2000s, PIs have been shown to have activity in vitro against a number of adult solid tumors, the results of which are reported in a landmark paper by Gills et al.13 Here, a 60-cell line panel of malignancies, including breast, colon, lung, renal, leukemia, and melanoma, were treated with nelfinavir (NFV) to reveal growth inhibition at ranges between 10−5 and 10−6 M.13 Additionally, they confirm cytotoxicity via apoptosis and provide evidence for mechanisms of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and autophagy.13

Supported by the findings from these studies, a number of clinical trials have been conducted, with promising early results (Table S1).14–18 For example, in treatment-resistant multiple myeloma, a phase I clinical trial of NFV with bortezimib showed partial response in one-third of patients, as well as safety and tolerability of NFV at doses used.17 Similarly, in a phase I trial of advanced stage non-small-cell lung cancer, NFV given in combination with radiation resulted in complete response in five of nine patients and partial response in the remaining four patients.18 Again, for a phase I trial in pancreatic cancer, NFV with radiation showed partial computed tomography (CT) responses in five of ten patients with a substantial reduction in tumor size atypical for radiation treatment alone.16 Finally, a phase I a clinical trial of NFV against various adult solid tumors also showed partial responses in up to 3 of 11 of evaluable patients with drug safety and tolerability.15 Additionally, there is some preclinical work on PI-derivatives showing promising results, including in leukemia.19–22

Despite the early promising data obtained from adult cancer studies, however, specific investigations directed against pediatric malignancies so far have not been reported. The present study describes the identification NFV-mediated cytotoxicity in pediatric leukemia cells and evaluation of mechanisms involved in this process. We also provide information on agents with potential for effective drug combination for evaluation in future treatment protocols.

Material and methods

Cell lines and cell culture

Cell lines used were SEM, C1, Molt3, TIB202, Molm13, and MV4-11, purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and are previously described.23 Additionally, the cell line Poetic2.2 was also employed – a line developed in our laboratory derived from a 13-year old pre-B acute lymphoblastic leukemia patient with a p16 deletion (Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board [CHREB] number: HREBA.CC-16-0286). Cells were maintained in Opti-MEM media (Gibco, Invitrogen Corporation, Burlington, ON, Canada) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL of penicillin, and 100 µg/mL of streptomycin (Gibco) and incubated in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were passaged approximately every 3–5 days, by centrifuging the suspension and resuspending the pellet in fresh media. Primary leukemic cells were obtained after ethics board approval (CHREB number: HREBA.CC-16-0286) and written informed consent from the parent or guardian. Normal lymphocytes were obtained from healthy volunteers after receipt of their verbal consent. Lymphocytes were isolated by density gradient centrifugation using Ficoll-Paque Plus (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Mississauga, ON, Canada).

Materials and reagents

The antimicrobial library, consisting of 112 compounds (68 antibacterials; 39 antivirals; and five other) was purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Burlington, ON, Canada) and contained the PIs, NFV, indinavir, amprenavir, and atazanavir. Additional PIs – lopinavir, ritonavir, darunavir (DRV), and saquinavir were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Compounds were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) to a stock concentration of 10 mM. Subsequent dilutions were made using cell culture media, as needed, to gain concentrations of 40 to 10−6 µM.

In vitro cytotoxicity assays

For the antimicrobial library screening, three cell lines were used in the testing, C1, Molt3, and Poetic2.2. Cells were passaged during exponential growth and seeded in 96-well plates (Grenier BioOne, Monroe, NC, USA) at 5×103 cells per well. Using four antimicrobial drug dilutions (0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10 µM) and the corresponding DMSO vehicle control, the drugs were added to the plates and incubated. After 4 days, cell viability was quantified using Alamar blue assay (Invitrogen, Burlington, ON, Canada) and cytotoxicity curves created. For the more detailed cytotoxicity curves, a larger dilution series was employed, and calculation of the half- and quarter-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50 and IC25, respectively) were determined for each drug based on independent cytotoxicity plots.

Drug combination studies

Pediatric leukemia cells were cultured as described above. SEM and Molm13 cell lines were selected as representative cell lines for the set and underwent the initial synergism screen against 35 chemotherapeutic agents, both conventional and novel. For the drug combination studies, the chemotherapy agents were first plated at 1 and 0.1 µM concentrations in triplicate wells of 96-well plates. NFV was added to each according to predetermined IC25 values. Cells were then plated at 5×103 cells/well. After 4 days of incubation, cell survival was quantified as above. Agents with the highest activity (ie, lowest IC50) in combination with NFV were selected for more detailed analyses against all seven cell lines to confirm the consistency of the findings across the broader panel. Various concentrations, ranging from 10 to 10−6 µM, were added to the wells alone or in combination with the corresponding IC25 of NFV for that cell line. Cell numbers and viability were determined after 4 days. The combination indices (CIs) were determined as previously described,24 where a CI <1 indicates synergy between the agents, CI =1 indicates that the agents are working additively, and CI >1 indicates that the agents are antagonistic.

Target modulation analyses

Target modulation by PIs was determined by Western blot analyses. Briefly, cells were incubated with the PI or appropriate control for 6, 12, or 24 h, as indicated, then lysed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay-based lysis buffer containing phosphatase and PIs. Lysates were resolved and transferred electrophoretically, and then probed using specific antibodies (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA; and AbCam, Cambridge, UK).

Results

PIs show potential as antileukemics

Testing of the antimicrobial library against a panel of leukemia cell lines revealed several compounds with cytotoxic effects (data not shown), including several drugs from the antiviral class, the HIV PIs. As a group, these agents showed a class-effect cytotoxicity at the upper 10 µM concentration of the screen, reaching IC20–25 for NFV, ritonavir, and lopinavir. This provided the initial suggestion to further investigate this class of agents.

PIs as a class are cytotoxic to leukemia

Extending the findings from the initial screen, eight different US Food and Drug Administration-approved PIs were tested for cytotoxicity against the seven pediatric leukemia cell lines. Their IC50 values are reported in Table 1 and range from 1 to >40 µM. As a comparator for clinically relevant plasma levels, the table also includes the typical drug levels obtained from HIV dosing regimens for each of the corresponding PIs. Boxes have been color-coded according to presumed feasibility of achieving that level in the plasma based on current HIV dosing regimens.25,26 Overall, the PIs with the most consistent activity across cell lines was NFV. Lopinavir, ritonavir, and saquinavir also showed activity against many of the cell lines tested.

Table 1.

Summary of IC50 values (µM) for eight FDA-approved HIV-protease inhibitors tested against seven different pediatric leukemia cell lines

| Amprenavir | Atazanavir | Darunavir | Indinavir | Lopinavir | NFV | Ritonavir | Saquinavir | Cell line comments | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEM | >40 | >40 | >40 | >40 | >40 | 17.4±5.8 | 17.5 | 28 | ALL; MLL-AF4 with an e9-e4 fusion |

| C1 | >40 | >40 | >40 | >40 | 17 | 13.8±0.4 | >40 | >40 | pre-B ALL |

| Molt3 | >40 | 24 | >40 | >40 | 35 | 16±1.4 | >40 | 30 | T-ALL |

| Poetic2.2 | >40 | >40 | >40 | >40 | 23 | 13.3±0.4 | 35 | >40 | ALL; pl6 deletion on relapse |

| MV4-11 | >40 | 8 | >40 | >40 | 4 | 8.7±5.9 | 6.5 | 27 | Biphenotypic B myelomonocytic leukemia; ITD of FLT3 |

| Molml3 | >40 | 7.5 | >40 | >40 | 1 | 8.2±7.0 | 4.5 | 6.5 | AML FAB M5a; ITD of FLT3 |

| TIB202 | >40 | >40 | >40 | >40 | >40 | 15.0±0.7 | >40 | 30 | AML; MLL-AF9 fusion gene |

| Plasma levela | 5–15 µM | 0.4–l µM | 10–20 µM | 8–20 µM | 5–20 µM | 6–10 µM | 7–11 µM | 1–4 µM |

Notes:

Per standard HIV dosing regimen.21,22 IC50 values achievable in the plasma via current HIV dosing regimens are highlighted in green; possibly achievable are in yellow; and less likely achievable are in red.

Abbreviations: ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration; ITD, internal tandem deletion; NFV, nelfinavir.

NFV shows selective targeting of leukemic cells

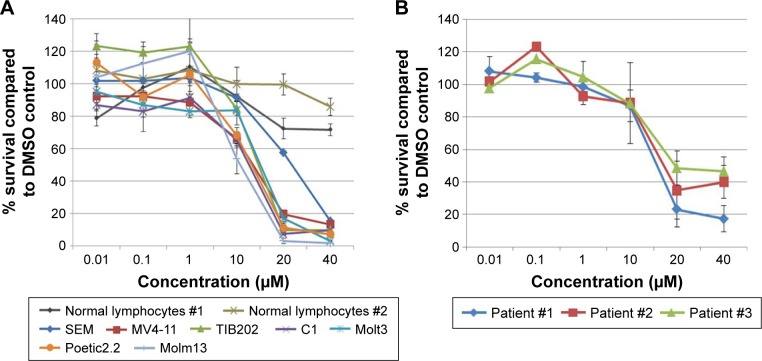

Given the findings from the class analyses, NFV was selected for more detailed cytotoxicity assays. Assessment of activity against seven cell lines gave IC50s ranging from 1 to 24 µM (Figure 1A). To determine the degree of selectivity of NFV toward leukemia cells, two populations of normal lymphocytes from healthy volunteers were also screened and showed minimal cytotoxicity at the upper concentrations tested (Figure 1A). Efficacy against primary leukemic cells was also demonstrated, showing analogous cytotoxicity curves with IC50 ranging from 16–20 µM (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Cytotoxicity assays of NFV against seven pediatric leukemia cell lines. Normal lymphocyte cytotoxicity is included for control. For the cell lines, plots are representative of at least triplicate independent experiments. (B) Cytotoxicity of NFV against primary leukemia cells.

Abbreviations: DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; NFV, nelfinavir.

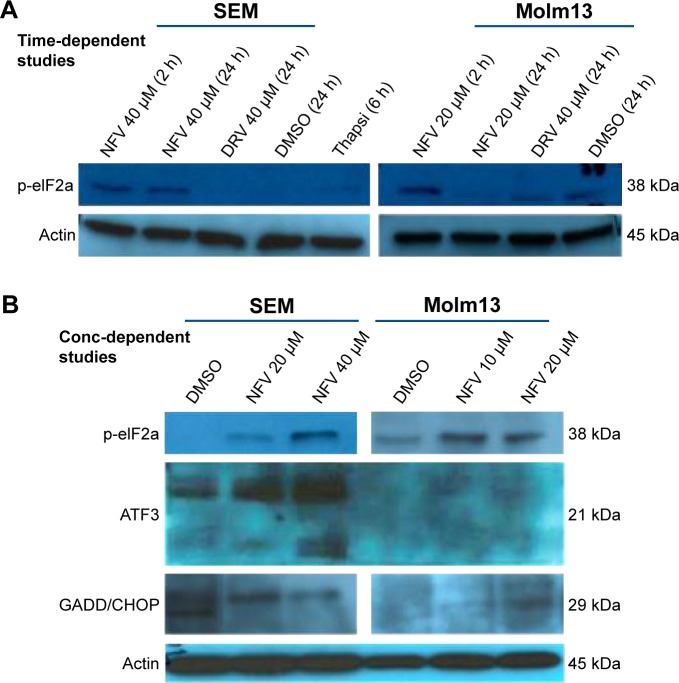

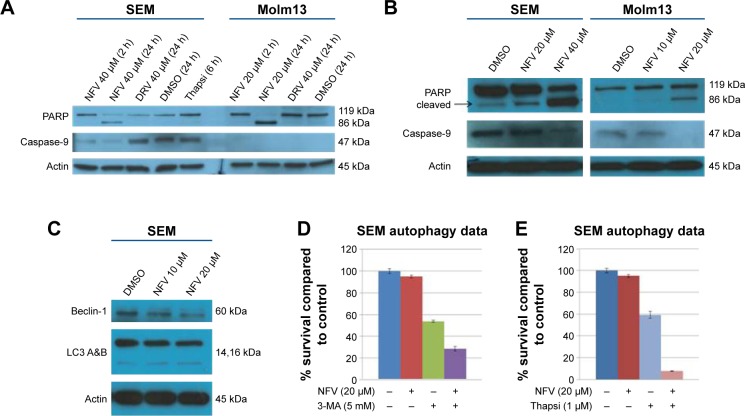

NFV induces ER stress, leading to autophagy and apoptosis

To delineate the underlying mechanisms of NFV on leukemia, we selected two of the above cell lines, SEM (an ALL cell line) and Molm13 (an AML cell line). Here, we show that treatment of these cells with NFV induces ER stress in the cell, as shown by elevated levels of the phosphorylated ER stress marker, eIF2α – a protein subunit that controls the initiation of mRNA translation. In its phosphorylated form, P-eIF2α prevents the further translation of proteins, reducing the ER workload in an attempt to allow the cell to recover.27 When cells are treated with NFV, a concentration- and time-dependent increase in this marker was observed (Figure 2). Also, there is simultaneous elevation of a downstream marker, CHOP, and an additional stress signaling marker, ATF3. This added cellular stress may subsequently induce the processes of autophagy and apoptosis (Figure 3). Immunoblots of autophagy markers show relatively stable levels of Beclin-1 and LC3B), in the treated and untreated cells (Figure 3C and F), consistent with the complexity and specificity of measuring autophagy in such systems.28 We thus show additional support of the cells’ reliance on this pathway through the use of autophagy inhibitors, 3-methyladenine and thapsigargin, which result in significant increase in cell death when the cell cannot rely on this pathway (Figure 3D, E, G, and H). Analysis of apoptosis markers shows increasing cleavage of both PARP and caspase-9 (via loss of the whole caspase-9) in both a time- and concentration-dependent manner, supporting cytotoxicity through apoptosis (Figure 3A and B). As a negative control, we included darunavir – a PI with no cytotoxic effects at the doses tested, and it is noted that DRV does not induce elevation of any of the stress or apoptosis markers.

Figure 2.

ER stress induced in NFV-treated and untreated cells.

Notes: Immunoblots of (A) time-dependent and (B) concentration-dependent effects. DRV has been included as a negative control, as it was found to be inactive at doses tested in the cytotoxicity assays. Then, upper incubation for each of the lysates employed above was 24 hour for SEM, and 12 hour for Molm13.

Abbreviations: Conc, concentration; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; DRV, darunavir; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; NFV, nelfinavir.

Figure 3.

Autophagy and apoptosis in NFV-treated and untreated cells.

Notes: Immunoblots of (A) time-dependent and (B) concentration-dependent effects. The Molm13 cell line was treated with an upper concentration of 20 µM NFV, while the SEM line was treated with 40 µM (per results of prior cytotoxicity assays). Autophagy in SEM treated with nelfinavir (C) and effects of cell survival with NFV alone and in combination with two different autophagy inhibitors, 3-methyladenine (D) and thapsigargin (E) treated for 96 h. Autophagy in Molm13 treated with nelfinavir for 12 h (F) and effects of cell survival with NFV alone and in combination with two different autophagy inhibitors, 3-methyladenine (G) and thapsigargin (H) treated for 48 h.

Abbreviations: 3-MA, 3-methyladenine; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; DRV, darunavir; NFV, nelfinavir; Thapsi, thapsigargin.

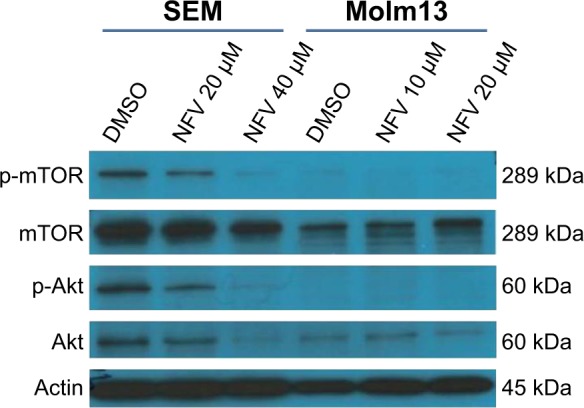

NFV inhibits Akt and mTOR signaling

Akt and mTOR signaling pathways are central to cellular proliferation and regulation of apoptosis in cells and are often upregulated in many types of cancers.29 To determine the effects of NFV on these pathways, immunoblots were performed and show decreased phosphorylation of both Akt and mTOR with increasing concentrations of NFV (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cell signaling influence of NFV.

Note: Cell lines were treated for 24 h with NFV, with concentrations shown (concentrations determined per results of prior cytotoxicity and time assays).

Abbreviations: DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; NFV, nelfinavir.

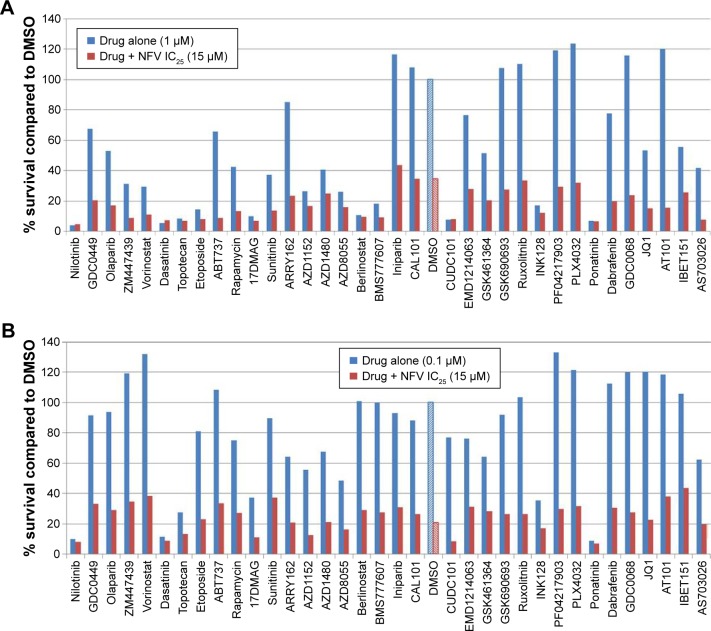

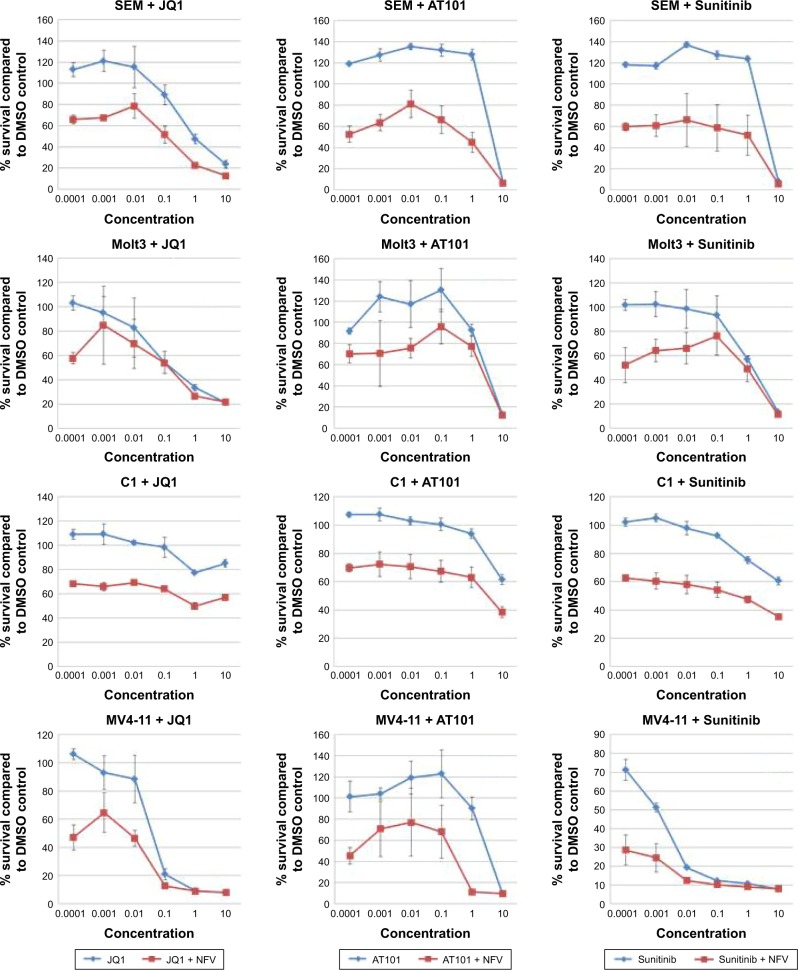

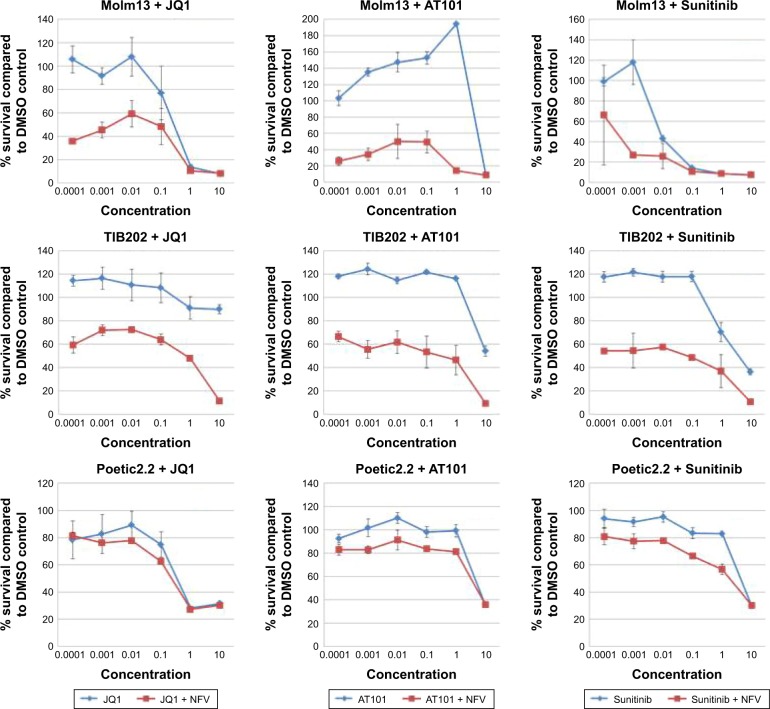

NFV activity shows synergy with specific antileukemic agents

To determine which drugs NFV could be combined with to provide enhanced antileukemic activity, the SEM and Molm13 cell lines were screened against a panel of 35 different chemotherapy agents, both novel and conventional, with diverse mechanisms of action. The drug panel was screened alone and in combination with NFV at two different concentrations, 1 µM and 0.1 µM (Figures 5 and S1). Based on these results, compounds that showed more than an additive change in cytotoxicity when combined were selected for more detailed studies to assess synergy and determine CIs. Agents selected were JQ1 (BET inhibitor), AT101 (Bcl-2 family inhibitor), and Sunitinib (TK inhibitor). CIs when tested across the panel of leukemia cell lines ranged from 0.07 to 0.95 for JQ1; 0.05–1.8 for AT101; and 0.013–0.6 for Sunitinib, implying synergistic effects across most cell lines (Figure 6; Table 2).

Figure 5.

Combination studies with known chemotherapy regimens in SEM.

Notes: Drugs were plated in 96-well plates alone and in combination with the IC25 of NFV, determined from the corresponding cell line cytotoxicity screens. (A) Plated drugs at 1 µM final concentration; (B) drugs at 0.1 µM. The cells were then added to each (5,000 cells/well) and incubated for four days before being read by Alamar blue assay. The control (DMSO) and NFV alone are shown with patterned bars.

Abbreviations: DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; IC25, quarter-maximal inhibitory concentration; NFV, nelfinavir.

Figure 6.

Combination studies of NFV with JQ1, Sunitinib, and AT101.

Notes: Drugs were plated in 96-well plates alone and in combination with NFV. The drug in question had dilutions ranging from 0.001 to 10 µM, while NFV was held constant at the cell line’s IC25 for NFV. The cells were then added to each (5,000 cells/well) and incubated for four days before being read by Alamar blue assay.

Abbreviations: DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; IC25, quarter-maximal inhibitory concentration; NFV, nelfinavir.

Table 2.

Combination indices of nelfinavir in combination with JQ1, AT101, and Sunitinib

| Cell line | JQ1 | AT101 | Sunitinib |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEM | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.60 |

| Molm13 | 0.18 | 0.056 | 0.34 |

| C1 | 0.2 | 0.70 | 0.065 |

| Molt3 | 0.97 | 1.2 | 0.37 |

| Poetic2.2 | 0.73 | 1.8 | 1.2 |

| MV4-11 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.065 |

| TIB202 | 0.071 | 0.11 | 0.013 |

Discussion

The acute and long-term toxicities of chemotherapy regimens used to treat refractory and relapsed pediatric leukemia have prompted the search for newer, safer agents. Here, through a search of antimicrobials, we identify the HIV PIs, with their decades of use and availability of pharmacokinetic and toxicity data, as potential candidates for the safe combination and incorporation into chemotherapy regimens.

The PIs have only just begun to be noticed for their anticancer properties with preliminary associations made in HIV patients with malignancies.7,8 NFV, in particular, has received the most attention with preliminary studies emerging in numerous adult malignancies, including castration-resistant prostate cancer,30,31 rectal cancer,32,33 pancreatic cancer,34 breast cancer,35 and lung cancer14,18,36 (Table S1). Though never before reported in pediatric cancers, our current work on pediatric leukemias suggest that NFV would also have significant antileukemic properties, with IC50s ranging from 1 to 15 µM – concentrations that are physiologically obtainable based on current oral HIV dosing regimens.25,26

The mechanism by which NFV exerts its effects appears to involve the induction of ER stress (Figure 2), which may drive the cell toward autophagy and ultimately, apoptosis (Figure 3). A similar mechanism has been shown in some adult cancers in vitro where NFV has been shown to induce ER stress in head and neck, breast, and prostate cancer cells.37–39 The autophagy induction is further characterized by the application of autophagy inhibitors, 3-methyladenine and thapsigargin, which greatly reduce cell survival when combined with NFV (Figure 3C–H). This is consistent with previous findings where, when similar inhibitors resulted in lethal or near-lethal cellular toxicity.40 When the cancer cells’ homeostatic mechanisms are overwhelmed, cells undergo apoptosis. Here, we also show elevated levels of apoptosis markers, including cleaved PARP and caspase-9, in response to NFV treatment, supporting this mechanism of cell death (Figure 3B).

NFV also acts by targeting crucial cell-signaling pathways, such as Akt and mTOR.40 Here, we show that these mechanisms are present in its effect in pediatric leukemia cells, showing both time- and concentration-dependent effects on cell signaling (Figure 4). Again, such signaling pathways are highlighted as a key target and one of the hallmarks in cancer.41 Interestingly, it is this off-target effect on mTOR that has also been shown to play a role in the treatment of HIV infection.42 Additional pathways implicated in the literature with NFV include oxidative stress mechanisms,26,43 decreased angiogenesis,14,44 and cell cycle arrest.14,26,45

In future clinical trials, the inclusion of NFV in combination, rather than as a single agent, would provide additional benefits with enhanced tumor killing, reduction of chemotherapy-specific toxicities, and, ideally, avoidance of therapy resistance. NFV has already been considered in combination with other chemotherapy agents in clinical trials, including with doxorubicin for breast cancer35 and with bortezomib for myeloma.17 For both cases, NFV was able to act synergistically with the standard therapeutics to overcome drug resistance. In the former case, NFV was able to enhance the effects of doxorubicin against a multidrug-resistant breast cancer cell line (MCF-7/Dox), considered to be multifactorial and involving suppression of P-gp-mediated drug efflux, inhibition of Akt activation, and induction ER stress, leading to autophagy.35 Similarly, in the case of myeloma, NFV was able to enhance bortezomib to overcome both bortezomib and carfilzomib resistance, again, attributed to ER stress leading to increased unfolded protein response (UPR) pathway-induced apoptosis.46 Additionally, owing to its influence on cellular stress, NFV has also been considered in combination with radiation therapy.33,39,47,48 To consider NFV’s application in the treatment of pediatric leukemia, we examined a panel of mechanistically diverse chemotherapeutic drugs in combination with NFV. This screen revealed synergy with the BET inhibitor, JQ1, with CIs ranging from 0.07 to 0.97. Based on the evidence of NFV’s influence on cellular stress and signaling targets, synergy with agents that alter epigenetic processes may be postulated. Indeed, there is evidence of synergy in literature of epigenetic drugs with both ER stress inducers and mTOR inhibitors.49–51 Similarly, for other pathways revealed, the Bcl-2 family inhibitor, AT101, and the TK inhibitor, Sunitinib, synergy with drugs that induce ER stress have been shown previously.36,52 For these combinations, in our studies, CIs ranged from 0.05 to 1.8 and 0.013 to 0.6, respectively, providing evidence for their use together.

Conclusion

Pediatric leukemia remains a critical area for ongoing research as our current therapies remain toxic to healthy cells and relapses of chemoresistant-disease continue to occur at unacceptable rates. Here we show that HIV PIs, namely NFV, that has been employed for decades against the HIV virus in both adults and children, has selective anticancer effects with a therapeutic window compared to normal lymphocytes. We have also identified the potential mechanisms behind this observation. Finally, we show that the drug is able to act synergistically with certain currently approved antileukemic agents providing the framework to design of a future in vivo studies and subsequently early-phase clinical trials for refractory leukemia in children.

Supplementary materials

Combination studies with known chemotherapy regimens in Molm13.

Notes: Drugs were plated in 96-well plates alone and in combination with the IC50 of NFV, determined from the corresponding cell line cytotoxicity screens. (A) Plated drugs at 1 µM final concentration; (B) drugs at 0.1 µM. The cells were then added to each (5,000 cells/well) and incubated for four days before being read by Alamar blue assay. The control (DMSO) and NFV alone are shown with patterned bars.

Abbreviations: DMSO, dimetthylsulfoxide; IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration; NFV, nelfinavir.

Table S1.

Summary of clinical trials involving NFV to date (as per the NCI Clinical Trials Database)

| Protocol | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| NCT 0145106 | Solid tumors: A phase I trial of NFV (viracept) in adults with solid tumors |

| NCT 00436735 | Solid tumors: NFV in treating patients with metastatic, refractory, or recurrent solid tumors |

| NCT 02080416 | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, Kaposi sarcoma, gastric cancer, nasopharyngeal cancer, EBV, Castleman Disease: NFV for the treatment of gammaherpesvirus-related tumors |

| NCT 00589056 | NSCLC: NFV, radiation therapy, cisplatin, and etoposide in treating patients with stage III non-small-cell lung cancer that cannot be removed by surgery |

| NCT 01068327 | Pancreatic cancer: stereotactic radiation therapy, NFV mesylate, gemcitabine hydrochloride, leucovorin calcium, and fluorouracil in treating patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer |

| NCT 01925378 | Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a phase II single-arm intervention trial of NFV in patients with grade 2/3 or 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia |

| NCT 01959672 | Pancreatic cancer: NFV mesylate in treating patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer |

| NCT 01079286 | Renal cell cancer: study of NFV and temsirolimus in patients with advanced cancers |

| NCT 00704600 | Rectal cancer: NFV, a phase I/phase II rectal cancer study |

| NCT 01065844 | Adenoid cystic cancer: NFV in recurrent adenoid cystic cancer of the head and neck |

| NCT 01164709 | Hematologic cancer: NFV mesylate and bortezomib in treating patients with relapsed or progressive advanced hematologic cancer |

| NCT 01086332 | Pancreatic cancer: evaluation of NFV and chemoradiation for pancreatic cancer |

| NCT 01485731 | Cervical cancer: safety study of NFV + cisplatin + pelvic radiation therapy to treat cervical cancer |

| NCT 02024009 | Pancreatic cancer: systemic therapy and chemoradiation in advanced localized pancreatic cancer: 2 |

| NCT 00915694 | Glioblastoma: NFV, radiation therapy, and temozolomide in treating patients with glioblastoma multiforme |

| NCT 01108666 | Non-small-cell lung cancer: proton beam radiation with concurrent chemotherapy and NFV for inoperable stage III non-small-cell lung cancer |

| NCT 00791336 | Study to evaluate using NFV with chemoradiation for non-small-cell lung cancer |

| NCT 02207439 | Larynx carcinoma: A phase II of NFV, given with definitive, concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced, human papilloma virus-negative, squamous cell carcinoma larynx |

| NCT 01020292 | Glioma: NFV and concurrent radiation and temozolomide in patients with WHO grade IV glioma |

| NCT 01555281 | Myeloma: NFV and lenalidomide/dexamethasone in patients with progressive multiple myeloma that have failed lenalidomide-containing therapy |

| NCT 01728779 | Metastatic lesions of the lung, liver, or bone: stereotactic body radiation with NFV for oligometastases |

| NCT 00233948 | Liposarcoma: NFV mesylate in treating patients with recurrent, metastatic, or unresectable liposarcoma |

| NCT 02188537 | Myeloma: NFV as bortezomib-sensitizing drug in patients with proteasome inhibitor nonresponsive myeloma |

| EudraCT#: 2008-006302-42 University of Oxford | Pancreatic cancer: a phase II study in patients with locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma: ARC-II – Akt-inhibition by NFV plus chemoradiation with gemcitabine and cisplatin |

Abbreviations: EBV, Ebstein-Barr virus; NCI, National Cancer Institute; NFV, nelfinavir; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; WHO, World Health Organization.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by the POETIC Foundation, Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation, and the Kids Cancer Care Foundation of Alberta (KCCFA).

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Adamson PC. Improving the outcome for children with cancer: development of targeted new agents. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(3):212–220. doi: 10.3322/caac.21273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guest EM, Stam RW. Updates in the biology and therapy for infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2017;29(1):20–26. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taga T, Tomizawa D, Takahashi H, Adachi S. Acute myeloid leukemia in children: Current status and future directions. Pediatr Int. 2016;58(2):71–80. doi: 10.1111/ped.12865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson GH. Use of fludarabine in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Hematol J. 2004;5(Suppl 1):S62–S67. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duivenvoorden WC, Hirte HW, Singh G. Use of tetracycline as an inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase activity secreted by human bone-metastasizing cancer cells. Invasion Metastasis. 1997;17(6):312–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flexner C. HIV drug development: the next 25 years. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6(12):959–966. doi: 10.1038/nrd2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Monini P, Sgadari C, Toschi E, Barillari G, Ensoli B. Antitumour effects of antiretroviral therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(11):861–875. doi: 10.1038/nrc1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chow WA, Jiang C, Guan M. Anti-HIV drugs for cancer therapeutics: back to the future? Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(1):61–71. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70334-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidtke G, Holzhütter HG, Bogyo M, et al. How an inhibitor of the HIV-I protease modulates proteasome activity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(50):35734–35740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.50.35734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sgadari C, Barillari G, Toschi E, et al. HIV protease inhibitors are potent anti-angiogenic molecules and promote regression of Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Med. 2002;8(3):225–232. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sgadari C, Monini P, Barillari G, Ensoli B. Use of HIV protease inhibitors to block Kaposi’s sarcoma and tumour growth. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4(9):537–547. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikezoe T, Saito T, Bandobashi K, Yang Y, Koeffler HP, Taguchi H. HIV-1 protease inhibitor induces growth arrest and apoptosis of human multiple myeloma cells via inactivation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3(4):473–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gills JJ, Lopiccolo J, Tsurutani J, et al. Nelfinavir, A lead HIV protease inhibitor, is a broad-spectrum, anticancer agent that induces endoplasmic reticulum stress, autophagy, and apoptosis in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(17):5183–5194. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koltai T. Nelfinavir and other protease inhibitors in cancer: mechanisms involved in anticancer activity. F1000Research. 2015;4:9. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.5827.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blumenthal GM, Gills JJ, Ballas MS, et al. A phase I trial of the HIV protease inhibitor nelfinavir in adults with solid tumors. Oncotarget. 2014;5(18):8161–8172. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brunner TB, Geiger M, Grabenbauer GG, et al. Phase I trial of the human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitor nelfinavir and chemo-radiation for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(16):2699–2706. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Driessen C, Kraus M, Joerger M, et al. Treatment with the HIV protease inhibitor nelfinavir triggers the unfolded protein response and may overcome proteasome inhibitor resistance of multiple myeloma in combination with bortezomib: a phase I trial (SAKK 65/08) Haematologica. 2016;101(3):346–355. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.135780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rengan R, Mick R, Pryma D, et al. A phase I trial of the HIV protease inhibitor nelfinavir with concurrent chemoradiotherapy for unresectable stage IIIA/IIIB non-small cell lung cancer: a report of toxicities and clinical response. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(4):709–715. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182435aa6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maksimovic-Ivanic D, Fagone P, McCubrey J, Bendtzen K, Mijatovic S, Nicoletti F. HIV-protease inhibitors for the treatment of cancer: Repositioning HIV protease inhibitors while developing more potent NO-hybridized derivatives? Int J Cancer. 2017;140(8):1713–1726. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh R, Kesharwani P, Mehra NK, Singh S, Banerjee S, Jain NK. Development and characterization of folate anchored Saquinavir entrapped PLGA nanoparticles for anti-tumor activity. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2015;41(11):1888–1901. doi: 10.3109/03639045.2015.1019355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.You J, He Z, Chen L, et al. CH05-10, a novel indinavir analog, is a broad-spectrum antitumor agent that induces cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy. Cancer Sci. 2010;101(12):2644–2651. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01724.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maksimovic-Ivanic D, Mojic M, Bulatovic M, et al. The NO-modified HIV protease inhibitor as a valuable drug for hematological malignancies: Role of p70S6K. Leuk Res. 2015;39(10):1088–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jayanthan A, Ruan Y, Truong TH, Narendran A. Aurora Kinases as Druggable Targets in Pediatric Leukemia: Heterogeneity in Target Modulation Activities and Cytotoxicity by Diverse Novel Therapeutic Agents. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e102741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chou TC. Drug combination studies and their synergy quantification using the Chou-Talalay method. Cancer Res. 2010;70(2):440–446. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Acosta EP, Kakuda TN, Brundage RC, Anderson PL, Fletcher CV. Pharmacodynamics of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitors. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(Suppl 2):S151–S159. doi: 10.1086/313852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiang T, Du L, Pham P, Zhu B, Jiang S. Nelfinavir, an HIV protease inhibitor, induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in human cervical cancer cells via the ROS-dependent mitochondrial pathway. Cancer Lett. 2015;364(1):79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oslowski CM, Urano F. Measuring ER stress and the unfolded protein response using mammalian tissue culture system. Methods Enzymol. 2011;490:71–92. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385114-7.00004-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barth S, Glick D, Macleod KF. Autophagy: assays and artifacts. J Pathol. 2010;221(2):117–124. doi: 10.1002/path.2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altomare DA, Testa JR. Perturbations of the AKT signaling pathway in human cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24(50):7455–7464. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guan M, Fousek K, Chow WA. Nelfinavir inhibits regulated intramembrane proteolysis of sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 and activating transcription factor 6 in castration-resistant prostate cancer. FEBS J. 2012;279(13):2399–2411. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guan M, Su L, Yuan YC, Li H, Chow WA. Nelfinavir and nelfinavir analogs block site-2 protease cleavage to inhibit castration-resistant prostate cancer. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9698. doi: 10.1038/srep09698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hill EJ, Roberts C, Franklin JM, et al. Clinical trial of oral nelfinavir before and during radiation therapy for advanced rectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(8):1922–1931. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyn RE, Krishnan S, Skinner HD. Everything old is new again: using nelfinavir to radiosensitize rectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(8):1834–1836. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson JM, Fokas E, Dutton SJ, et al. ARCII: A phase II trial of the HIV protease inhibitor Nelfinavir in combination with chemoradiation for locally advanced inoperable pancreatic cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2016;119(2):306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chakravarty G, Mathur A, Mallade P, et al. Nelfinavir targets multiple drug resistance mechanisms to increase the efficacy of doxorubicin in MCF-7/Dox breast cancer cells. Biochimie. 2016;124:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawabata S, Gills JJ, Mercado-Matos JR, et al. Synergistic effects of nelfinavir and bortezomib on proteotoxic death of NSCLC and multiple myeloma cells. Cell Death Dis. 2012;3:e353. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cho HY, Thomas S, Golden EB, et al. Enhanced killing of chemo-resistant breast cancer cells via controlled aggravation of ER stress. Cancer Lett. 2009;282(1):87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathur A, Abd Elmageed ZY, Liu X, et al. Subverting ER-stress towards apoptosis by nelfinavir and curcumin coexposure augments docetaxel efficacy in castration resistant prostate cancer cells. PloS One. 2014;9(8):e103109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu R, Zhang L, Yang J, et al. HIV protease Inhibitors sensitize human head and neck squamous carcinoma cells to radiation by activating endoplasmic reticulum stress. PloS One. 2015;10(5):e0125928. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson CE, Hunt DK, Wiltshire M, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and cell death in mTORC1-overactive cells is induced by nelfinavir and enhanced by chloroquine. Mol Oncol. 2015;9(3):675–688. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donia M, McCubrey JA, Bendtzen K, Nicoletti F. Potential use of rapamycin in HIV infection. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70(6):784–793. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03735.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ben-Romano R, Rudich A, Etzion S, et al. Nelfinavir induces adipocyte insulin resistance through the induction of oxidative stress: differential protective effect of antioxidant agents. Antivir Ther. 2006;11(8):1051–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pore N, Gupta AK, Cerniglia GJ, Maity A. HIV protease inhibitors decrease VEGF/HIF-1alpha expression and angiogenesis in glioblastoma cells. Neoplasia. 2006;8(11):889–895. doi: 10.1593/neo.06535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang W, Mikochik PJ, Ra JH, et al. HIV protease inhibitor nelfinavir inhibits growth of human melanoma cells by induction of cell cycle arrest. Cancer Res. 2007;67(3):1221–1227. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kraus M, Bader J, Overkleeft H, Driessen C. Nelfinavir augments proteasome inhibition by bortezomib in myeloma cells and overcomes bortezomib and carfilzomib resistance. Blood Cancer J. 2013;3:e103. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2013.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goda JS, Pachpor T, Basu T, Chopra S, Gota V. Targeting the AKT pathway: Repositioning HIV protease inhibitors as radiosensitizers. Indian J Med Res. 2016;143(2):145–159. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.180201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin A, Maity A. Molecular pathways: a novel approach to targeting hypoxia and improving radiotherapy efficacy via reduction in oxygen demand. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(9):1995–2000. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee DH, Qi J, Bradner JE, et al. Synergistic effect of JQ1 and rapamycin for treatment of human osteosarcoma. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(9):2055–2064. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park MA, Zhang G, Martin AP, et al. Vorinostat and sorafenib increase ER stress, autophagy and apoptosis via ceramide-dependent CD95 and PERK activation. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7(10):1648–1662. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.10.6623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cottini F, Anderson K. Novel therapeutic targets in multiple myeloma. Clin Advan Hematol Oncol. 2015;13(4):236–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clarke R, Cook KL, Hu R. Endoplasmic reticulum stress, the unfolded protein response, autophagy, and the integrated regulation of breast cancer cell fate. Cancer Res. 2012;72(6):1321–1331. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Combination studies with known chemotherapy regimens in Molm13.

Notes: Drugs were plated in 96-well plates alone and in combination with the IC50 of NFV, determined from the corresponding cell line cytotoxicity screens. (A) Plated drugs at 1 µM final concentration; (B) drugs at 0.1 µM. The cells were then added to each (5,000 cells/well) and incubated for four days before being read by Alamar blue assay. The control (DMSO) and NFV alone are shown with patterned bars.

Abbreviations: DMSO, dimetthylsulfoxide; IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration; NFV, nelfinavir.

Table S1.

Summary of clinical trials involving NFV to date (as per the NCI Clinical Trials Database)

| Protocol | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| NCT 0145106 | Solid tumors: A phase I trial of NFV (viracept) in adults with solid tumors |

| NCT 00436735 | Solid tumors: NFV in treating patients with metastatic, refractory, or recurrent solid tumors |

| NCT 02080416 | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, Kaposi sarcoma, gastric cancer, nasopharyngeal cancer, EBV, Castleman Disease: NFV for the treatment of gammaherpesvirus-related tumors |

| NCT 00589056 | NSCLC: NFV, radiation therapy, cisplatin, and etoposide in treating patients with stage III non-small-cell lung cancer that cannot be removed by surgery |

| NCT 01068327 | Pancreatic cancer: stereotactic radiation therapy, NFV mesylate, gemcitabine hydrochloride, leucovorin calcium, and fluorouracil in treating patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer |

| NCT 01925378 | Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a phase II single-arm intervention trial of NFV in patients with grade 2/3 or 3 cervical intraepithelial neoplasia |

| NCT 01959672 | Pancreatic cancer: NFV mesylate in treating patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer |

| NCT 01079286 | Renal cell cancer: study of NFV and temsirolimus in patients with advanced cancers |

| NCT 00704600 | Rectal cancer: NFV, a phase I/phase II rectal cancer study |

| NCT 01065844 | Adenoid cystic cancer: NFV in recurrent adenoid cystic cancer of the head and neck |

| NCT 01164709 | Hematologic cancer: NFV mesylate and bortezomib in treating patients with relapsed or progressive advanced hematologic cancer |

| NCT 01086332 | Pancreatic cancer: evaluation of NFV and chemoradiation for pancreatic cancer |

| NCT 01485731 | Cervical cancer: safety study of NFV + cisplatin + pelvic radiation therapy to treat cervical cancer |

| NCT 02024009 | Pancreatic cancer: systemic therapy and chemoradiation in advanced localized pancreatic cancer: 2 |

| NCT 00915694 | Glioblastoma: NFV, radiation therapy, and temozolomide in treating patients with glioblastoma multiforme |

| NCT 01108666 | Non-small-cell lung cancer: proton beam radiation with concurrent chemotherapy and NFV for inoperable stage III non-small-cell lung cancer |

| NCT 00791336 | Study to evaluate using NFV with chemoradiation for non-small-cell lung cancer |

| NCT 02207439 | Larynx carcinoma: A phase II of NFV, given with definitive, concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced, human papilloma virus-negative, squamous cell carcinoma larynx |

| NCT 01020292 | Glioma: NFV and concurrent radiation and temozolomide in patients with WHO grade IV glioma |

| NCT 01555281 | Myeloma: NFV and lenalidomide/dexamethasone in patients with progressive multiple myeloma that have failed lenalidomide-containing therapy |

| NCT 01728779 | Metastatic lesions of the lung, liver, or bone: stereotactic body radiation with NFV for oligometastases |

| NCT 00233948 | Liposarcoma: NFV mesylate in treating patients with recurrent, metastatic, or unresectable liposarcoma |

| NCT 02188537 | Myeloma: NFV as bortezomib-sensitizing drug in patients with proteasome inhibitor nonresponsive myeloma |

| EudraCT#: 2008-006302-42 University of Oxford | Pancreatic cancer: a phase II study in patients with locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma: ARC-II – Akt-inhibition by NFV plus chemoradiation with gemcitabine and cisplatin |

Abbreviations: EBV, Ebstein-Barr virus; NCI, National Cancer Institute; NFV, nelfinavir; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; WHO, World Health Organization.