Abstract

Background

Research suggests that adolescents with Down syndrome experience increased behavior problems as compared to age matched peers; however, few studies have examined how these problems relate to adaptive functioning. The primary aim of this study was to characterize behavior in a sample of adolescents with Down syndrome using two widely-used caregiver reports: the Behavioral Assessment System for Children, 2nd Edition (BASC-2) and Child Behavioral Checklist (CBCL). The clinical utility of the BASC-2 as a measure of behavior and adaptive functioning in adolescents with Down syndrome was also examined.

Methods

Fifty-two adolescents with Down syndrome between the ages of 12 and 18 (24 males) completed the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, 4th Edition (PPVT-IV) as an estimate of cognitive ability. Caregivers completed the BASC-2 and the CBCL for each participant.

Results

A significant proportion of the sample was reported to demonstrate behavior problems, particularly related to attention and social participation. The profile of adaptive function was variable, with caregivers most frequently rating impairment in skills related to activities of daily living and functional communication. Caregiver ratings did not differ by gender and were not related to age or estimated cognitive ability. Caregiver ratings of attention problems on the BASC-2 accounted for a significant proportion of variance in Activities of Daily Living (Adj R2 = 0.30), Leadership (Adj R2 = 0.30) Functional Communication (Adj R2 = 0.28, Adaptability (Adj R2 = 0.29), and Social Skills (Adj R2 = 0.17). Higher frequencies of symptoms related to social withdrawal added incremental predictive validity for Functional Communication, Leadership, and Social Skills. Convergent validity between the CBCL and BASC-2 was poor when compared with expectations based on the normative sample.

Conclusion

Our results confirm and extend previous findings by describing relationships between specific behavior problems and targeted areas of adaptive function. Findings are novel in that they provide information about the clinical utility of the BASC-2 as a measure of behavior and adaptive skills in adolescents with Down syndrome. The improved specification of behavior and adaptive functioning will facilitate the design of targeted intervention, thus improving functional outcomes and overall quality of life for individuals with Down syndrome and their families.

Keywords: Intellectual disability, adaptive behavior, Down syndrome, behavior problems, assessment

Introduction

Down syndrome is the most common genetic cause of intellectual disability, affecting 1 out of every 691 infants in the United States (Parker et al., 2010). Individuals with Down syndrome demonstrate a variable neuropsychological profile that is marked by a disproportionate weakness in verbal working memory (Silverman, 2007). Difficulties with independent self-care and adaptive functioning become apparent as skills become increasingly discrepant from age expectations. (Dykens, Hodapp, & Evans, 2006). Deficits in adaptive functioning and behavior problems significantly limit the ability of individuals with Down syndrome to live as independent adults (Hawkins, Eklund, James, & Foose, 2003).

Behavior problems in individuals with intellectual disability are frequently underdiagnosed due to factors including limited verbal ability, atypical presentation of symptomatology, limited verbal abilities, and a paucity of appropriate tools to facilitate diagnosis (Marston, Perry, & Roy, 1997; Reiss, Levitan, & McNally, 1982; Reiss, Levitan, & Szyszko, 1982; Rush, Bowman, Eidman, Toole, & Mortenson, 2004). Despite these limitations, studies have documented that between 18 and 30% of children with Down syndrome experience externalizing behavior problems, an incidence that is higher than that of their typically developing age matched peers (Capone, Goyal, Ares, & Lannigan, 2006; Gath & Gumley, 1986; Myers & Pueschel, 1991). A recent population-based study found that children with Down syndrome had significantly greater problems with attention and social skills as compared to chronologically age matched peers (Van Gameren-Oosterom, Fekkes, Buitendijk, et. al 2011). During adolescence and adulthood, individuals with Down syndrome are at significant risk for depressive symptomology (Collacott, Cooper, & McGrother, 1992; Holland, Hon, Huppert, & Stevens, 2000; Holland, Hon, Huppert, Stevens, & Watson, 1998; Nicham, Weitzdorfer, Hauser et al., 2003; van Gameren-Oosterom et al., 2013; Warren, Holroyd, & Folstein, 1989). Demographic factors most consistently associated with increased behavior problems include more severe intellectual disability and gender (Dykens, 2000; Dykens & Kasari, 1997; Dykens, Shah, Sagun et al., 2002; van Gameren-Oosterom, et al., 2013). Findings regarding gender are mixed, with some studies documenting evidence of increased behavior problems in males (van Gameren-Oosterom, et al., 2011 & 2013) and others finding evidence for increased problems in females (Dykens et al., 2002).

Behavior problems have been associated with impaired adaptive functioning in individuals with intellectual disability (de Ruiter, Dekker, Verhulst, & Koot, 2007) Dykens, et al., 2006) and in those with Down syndrome specifically (Borthwick-Duffy, Lane, & Widaman, 1997). Untreated behavior problems have been associated with deficits in educational and vocational attainment in individuals with intellectual disability, thus leading to reduced quality of life for individuals and family members (Foley, Jacoby, Girdler et al., 2013; Seltzer, Floyd, Greenberg, et al., 2005; Seltzer, Floyd, Greenberg, et al., 2009). As such, it is imperative to identify risk and resiliency factors influencing the developmental trajectory of behavior and adaptive skills in individuals with Down syndrome.

Few studies have explored behavior and adaptive skills specifically during adolescence, a time that is characterized by increased risk for mood and behavior problems in the general population. Using a cross-sectional design to explore caregiver reports of maladaptive behavior, Dykens and colleagues (2002) found evidence for significantly increased levels of internalizing behavior (e.g., social withdrawal) in groups of participants aged 10 to 13 and 14 to 19, when compared younger participants between the ages of 4 and 6. Group comparisons further suggested a decrease in externalizing symptoms during older adolescence and early adulthood (Dykens, Shah, Sagun, et al., 2002). In a study that aimed to characterize behavior problems in individuals with Down syndrome across the lifespan, Nicham and colleagues (2003) found significantly higher mean levels of externalizing behaviors in children aged 5 to 10, as compared to participants aged 10 to 30 (Nicham et al., 2003). Evidence for increased internalizing symptomatology in adolescents with Down syndrome when compared to typically developing age matched peers has been demonstrated in a population-based study (Van Gameren-Oosterom et al., 2013). Comparison of data from the same cohort during childhood supported these findings (van Gameren-Oosterom, et al., 2011). Increased understanding of factors related to the trajectory of behavior and adaptive function would allow for the development of targeted interventions aimed at improving outcomes for the broader population of individuals with neurodevelopmental disabilities.

The goal of the present study was to characterize behavior and adaptive functioning in a sample of adolescents with Down syndrome using caregiver ratings of behavior collected using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach 2001) and the Behavior Assessment System for Children, 2nd Edition (BASC-2; Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004). We hypothesized that adolescents with Down syndrome would demonstrate significantly increased levels of behavior problems when compared with age-matched peers from the normative sample from the CBCL and BASC-2. Our second hypothesis was that caregiver ratings of behavior would differ by participant age, with the frequency of reported internalizing symptoms increasing with age, and participant level of intellectual functioning, with those who demonstrated the lowest ability level rated as having more behavior problems. We did not make specific hypotheses regarding gender, given the contrasting findings in the literature.

Hypotheses regarding adaptive functioning were explored using caregiver ratings from the BASC-2 only, as this instrument contains scales that were specifically designed to characterize adaptive skills (Reynolds & Kemphaus, 2004). Recent studies have examined the utility of the adaptive functioning scales on the BASC-2 in mixed clinical samples (Papazoglou, Jacobson, & Zabel, 2013a & 2013b); however, to our knowledge no study has examined the clinical utility in children with intellectual disability. Our fist hypothesis was that higher frequency of caregiver reported behavior symptoms would be significantly and moderately associated with lower adaptive functioning skills. Given previous findings documenting attention problems, thought problems, and social withdrawal in adolescents with Down syndrome (Collacott, Cooper, & McGrother, 1992; Holland, Hon, Huppert, & Stevens, 2000; van Gameren-Oosterom et al., 2013), we hypothesized that these behaviors in particular would impact adaptive function.

Information regarding behavior is frequently collected using caregiver report instruments that compare reported frequencies of maladaptive behavior to expectations based on peers of similar age. Such instruments are particularly useful in busy clinic settings, as they require minimal time to complete and minimal training to administer. Caregiver ratings on the CBCL and BASC-2 have demonstrated excellent reliability and validity in clinical and nonclinical populations, including those with intellectual disability (Dekker, Nunn, Einfeld et al., 2002); however, studies of convergent validity are limited (Reynolds & Kemphaus, 2004; Bender, Auciello, Morrison, MacAllister, & Zaroff, 2008). Further, studies have raised questions regarding the sensitivity and specificity of the CBCL when used in typically developing children (e.g. Jensen, Salzberg, Richters, et al., 1993), as well as those with acquired neurologic injury (e.g., Bender, Auciello, Morrison, et al., 2008) and chronic medical conditions (e.g., Holmes, Respess, Greer, et al., 1998). With additional measures of response validity and adaptive function, the BASC-2 may potentially be more useful in clinical settings. As such, an exploratory aim of this study was to examine the validity of the BASC-2 in comparison with the CBCL.

Methods

Participants

Fifty-two adolescents with Trisomy 21 Down syndrome between the ages of 12 and 18 participated in a larger study of neuropsychological and behavioral functioning. Participants were primarily recruited from community agencies, clinical research databases, and clinician referrals. All clinician-referred participants were receiving interdisciplinary services from professionals that may be considered standard-of-care for children with Down syndrome (i.e., occupational and speech-language therapists, special educators, and developmental behavioral pediatricians). Participants recruited from research databases had previously completed studies at our institution and had indicated interest in being contacted for future studies. Community based referrals were obtained through the local chapters of the Down Syndrome Association or community fundraising events. Individuals with a diagnosis of Autistic Disorder, Asperger's Disorder, or Pervasive Developmental Disorder were not eligible for this study. Participants were additionally excluded based on a history positive for neurological illness or injury (i.e., seizures or perinatal stroke), substance use or abuse, substantial prematurity (birth weight of less than 2,000 grams), or ventilator use immediately after birth. Individuals currently being treated with stimulant medication were asked to discontinue the medication on the day of the study visit. Written informed consent and/or verbal assent were obtained from all participants and their parents or legal guardians; two participants were over the age of 18 and did not have legal guardians; these individuals provided their own written informed consent. The research protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Procedure

Caregivers of participants indicated interest in the study by responding to advertisements by phone or email. Twelve participants were excluded during phone screening process. Eight children were diagnosed with a pervasive developmental disorder, 2 had epilepsy, one had a previous neurological injury, and one required intubation shortly after birth. Caregivers completed a demographic questionnaire and behavior rating forms. Individuals with Down syndrome completed measures of neuropsychological functioning that were collected as part of a larger study. Study visits lasted between 1.5 to 2 hours and families were given 40 dollars in gift cards to compensate for time and travel expenses. Caregivers were sent a brief report summarizing results of the standardized tests completed as part of the protocol.

Study Measures

Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, 4th Edition (PPVT-IV; Dunn & Dunn, 2007)

On the PPVT-IV individuals are required to select the picture that best matched the word spoken by the examiner from four choices. Scores are age standardized (M = 100; SD = 10). Performance on the PPVT-III has been shown to strongly correlate with performance on the PPVT-IV in a subset of the PPVT-IV normative sample between 11 and 14 years of age (n = 66; r = .83; Dunn & Dunn, 2007). Further, there was no significant difference in performance on the two versions (MPPVT-III = 100.8, SD = 15.0; MPPVT-IV = 98.9, SD = 16.1, p=ns; Dunn & Dunn, 2007). Composite scores from the PPVT-III have been found to correlate highly (.90) with full scale IQ scores from the Wechsler Intelligence Scales for Children, Third Edition (Wechsler, 1991). Scores on earlier versions of the PPVT have been shown to be highly correlated with other measures of intelligence (e.g. Beck & Black, 1986; Childers, Durham, & Wilson 1994; Bell, Lassiter, Matthews, et al., 2001; Campbell, Bell, & Keith, 2001). The PPVT has been used as a measure of estimated IQ in studies of children who are typically developing (e.g. Mahone, Martin, Kates, et al., 2009), childhood survivors of brain tumors (Castellino, Tooze, Flowers et al., 2011) and in those with neurodevelopmental conditions (e.g. Jarrold, Baddeley, & Hewes, 2000).

Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; (Achenbach, 1991, 2001; Achenbach and Roscorla, 2001)

The CBCL contains 113 items from which eight syndrome scales (Anxious/Depressed, Withdrawn/Depressed, Somatic Complaints, Social Problems, Thought Problems, Attention Problems, Rule Breaking Behavior, and Aggressive Behavior) and three composite scales (Internalizing Symptoms, Externalizing Symptoms and Total Symptoms) are derived. Scores are age and gender standardized (M = 50; SD = 10). Test-retest correlations ranged from r = .95 to r = 1.00 for all scales over a one-week interval in the normative sample. Internal consistency is moderate to high for all composite and syndrome scales (α's = .80 - .94). CBCL Syndrome Scale T scores ≥ 70 (98th percentile) and Composite Scale T scores ≥ 64 reflect clinically significant problems. Scores at or above the 84th percentile (≥ 1SD above the mean) are considered to be “at-risk” for problem behavior in the normative sample.

Behavior Assessment Inventory for Children, 2nd Edition (BASC-2)

The BASC-2 contains 150 items from which nine clinical scales (Hyperactivity, Aggression, Conduct Problems, Anxiety, Depression, Somatization, Atypicality, Withdrawal, and Attention Problems), five adaptive scales (Adaptability, Social Skills, Leadership, Activities of Daily Living, and Functional Communication) and five composite scales (Internalizing, Externalizing, Behavior Symptoms Index, Adaptive Functioning, and Total Problems) are derived. The BASC-2 also includes three validity indices (F – negative response bias; L – positive response bias; and V – nonsensical statements) and two response set indices (Consistency Index and Response Pattern Index). Internal consistency reliability is high for all composite scales in the normative sample, including the Adaptive Composite (α's = .89 - .95). Reliability of the clinical and adaptive scales is moderate to high in the normative sample (α's = .70 - .90). Scores are age and gender standardized (M = 50, SD = 10). T-scores ≥ 70 (98th percentile) are indicative of clinically significant behavior problems, and adaptive scores ≤ 30 (2nd percentile). Scores at or above the 84th percentile (≥ 1 SD above the mean) in the normative sample were considered at risk for behavior problems. Scores at or below the 16th percentile (≥ 1 SD below the mean) in the normative sample are consider to be “at-risk” for behavior problems.

Statistical Analyses

Variable distributions were examined for normality in order to determine whether the use of parametric statistics was appropriate. Descriptive analyses were conducted to characterize the sample with regard to demographic factors. Group comparisons (X2, Fisher's Exact Test, or independent samples t-tests) were conducted to explore the impact of age, gender, and level of intellectual disability on behavior and adaptive functioning. Nonparametric tests were used to examine the effect of gender on the Anxious/Depressed and Withdrawn/Depressed CBCL scales, as well as BASC-2 Anxiety scale. Frequencies of elevated or at-risk scores were compared to expectations from the normative sample of the CBCL or BASC-2 with X2 analyses. All analyses were corrected for multiple comparisons. Stepwise multiple regression analyses were conducted to explore whether behavior problems predicted adaptive functioning using caregiver report from the BASC-2. Covariates and clinical scales from the BASC-2 were included as predictors if they were significantly related to criterion variable. Predictors entered the equation at p ≤ .05 and were removed at p ≥ .10. Cross validity predictive power was estimated using the Stein formula.

Fisher's Z calculations were performed to ascertain whether the strength of the relationship (convergent validity) between BASC-2 and CBCL scales differed between the sample of adolescents with Down syndrome and the normative sample. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated using the CBCL as the gold standard.

Results

Participant and Caregiver Demographics

Data were collected for 52 adolescents (24 males, 28 females) with Down syndrome who were between 12 and 18 years of age (Table 1). The group was balanced with respect to gender (χ2 = 0.31, p = .31). Ninety-four percent of the sample self-identified as Caucasian, 4% as African American, and 2% as Biracial. Sixty-nine percent of the sample was right-handed. PPVT-IV scores ranged from low average to significantly impaired when compared with normative expectations (M = 43.38, SD = 18.29). On average, female participants scored significantly higher than males on the PPVT-IV (t (50) = −2.14, p = .04, d = 0.60). Ninety-five percent of caregiver respondents were biological parents and 80% were mothers. The remaining 5% were guardians or adoptive parents. Ninety-one percent of the respondents had completed at least one year of college education, 37% held a Bachelor's degree, and 23% percent had a graduate degree or other professional training.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| (n = 52) M ± SD | Males (n = 24) M ± SD | Females (n = 28) M ± SD | p 2-sided | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 14.52 ± 2.19 | 14.85 ± 2.33 | 14.23 ± 2.06 | 0.314 |

| Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, 4th Edition - Standard Score | 43.38 ± 18.29 | 37.71 ± 18.20 | 48.25 ± 17.22 | 0.037 |

| N (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Recruitment Source | 0.059 | |||

| Community Agencies | 21 (40) | 7 (29) | 14 (50) | |

| Research Databases | 16 (35) | 9 (37) | 9 (37) | |

| Clinician Referrals | 9 (19) | 6 (25) | 4 (14) | |

| Other | 3 (6) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | |

| Race | 0.200 | |||

| Caucasian | 49 (94) | 22 (92) | 27 (96) | |

| African-American | 2 (4) | 2 (8) | . | |

| Mixed Race | 1(2) | . | 1 (4) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.463 | |||

| Non-Hispanic | 50 (96) | 22 (92) | 27 (96) | |

| Spanish/Hispanic/Latino | 2 (8) | 2 (8) | 1 (4) | |

N = 52. Standard Scores have a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. P-values are from Chi-Square tests to examine whether demographic characteristics differed significantly by gender.

Proportion of adolescents at risk for problems with behavior or adaptive skills

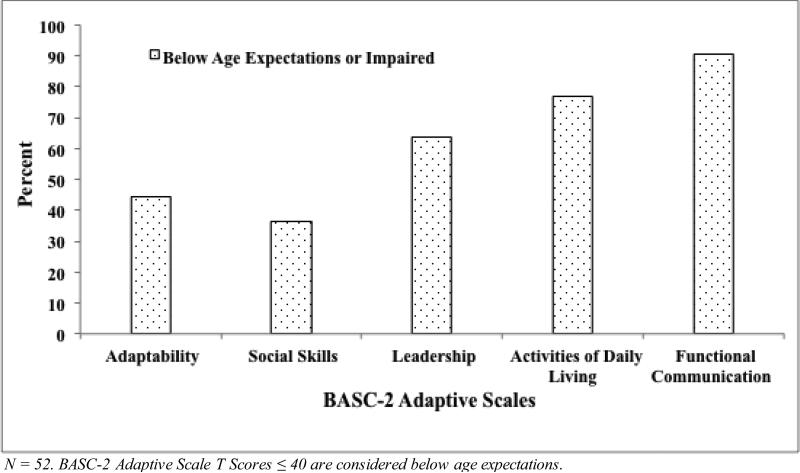

Table 2 provides details for caregiver ratings of behavior and adaptive function. There were no clinically significant group mean or median elevations of standard scores on the BASC-2 or CBCL. Participants with Down syndrome were more likely to demonstrate clinically significant behavior problems in several areas, including hyperactivity, atypicality, and withdrawal on the BASC-2, and social problems, thought problems, and attention problems on the CBCL. A substantial proportion of participants were rated as at-risk or impaired on the BASC-2 adaptive skill domains (Table 2; Figure 1). Notably, the proportion of participants demonstrating deficits in leadership and social skills on the BASC-2 did not differ significantly from the normative sample.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for BASC-2 and CBCL caregiver report and frequency of clinically significant elevations

| Mean ± SD | Median | n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASC-2 Composite Scores | ||||

| Externalizing Problems | 54.40 ± 9.00 | 54 | 3 (6) | 0.309 |

| Internalizing Problems | 45.48 ± 9.70 | 42.5 | 2 (4) | 0.500 |

| Behavior Symptoms Index | 57.44 ± 8.52 | 57.5 | 5 (10) | 0.103 |

| BASC-2 Clinical Scales | ||||

| Hyperactivity | 58.69 ± 10.68 | 59 | 10 (19) | 0.000 |

| Aggression | 49.73 ± 8.86 | 48.5 | 3 (6) | 0.309 |

| Conduct Problems | 53.63 ± 8.94 | 53 | 3 (6) | 0.310 |

| Anxiety | 42.62 ± 10.54 | 40.5 | 2 (4) | 0.500 |

| Depression | 49.23 ± 8.31 | 47.5 | 1 (2) | 0.752 |

| Somatization | 46.9 ± 8.21 | 44 | 1 (2) | 0.750 |

| Atypicality | 59.87 ± 11.38 | 59 | 14 (27) | 0.000 |

| Withdrawal | 58.33 ± 11.88 | 56 | 9 (17) | 0.007 |

| Attention Problems | 58.19 ± 6.88 | 58 | 4 (8) | 0.181 |

| BASC-2 Adaptive Scales | ||||

| Adaptive Skills Composite | 35.33 ± 8.26 | 35 | 14 (27) | 0.000 |

| Adaptability | 42.75 ± 8.72 | 43 | 5 (10) | 0.103 |

| Social Skills | 43.75 ± 9.35 | 43.5 | 4 (8) | 0.182 |

| Leadership | 38.46 ± 8.31 | 38 | 7 (14) | 0.030 |

| Activities of Daily Living | 34.12 ± 8.10 | 33.5 | 18 (35) | 0.000 |

| Functional Communication | 28.35 ± 9.90 | 27 | 30 (58) | 0.000 |

| CBCL Composite Scores | ||||

| Internalizing Problems | 54.21 ± 9.83 | 53 | 3 (6) | 0.000 |

| Externalizing Problems | 56.85 ± 7.64 | 56 | 13 (25) | 0.000 |

| CBCL Syndrome Scales | ||||

| Anxious/Depressed | 53.87 ± 6.23 | 51 | 2 (4) | 0.500 |

| Withdrawn/Depressed | 58.58 ± 7.72 | 57 | 5 (10) | 0.103 |

| Somatic Complaints | 57.67 ± 6.79 | 56 | 4 (8) | 0.181 |

| Rule-Breaking Behavior | 56.52 ± 5.13 | 57 | 5 (10) | 0.500 |

| Aggressive Behavior | 58.25 ± 6.97 | 58 | 3 (6) | 0.309 |

| Social Problems | 62.60 ± 6.57 | 61 | 7 (14) | 0.030 |

| Thought Problems | 63.92 ± 8.96 | 64 | 19 (37) | 0.000 |

| Attention Problems | 60.67 ± 6.45 | 61 | 6 (10) | 0.056 |

N = 52. All scores are standardized and have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. One-tailed p-values are from Fischer's Exact test comparing the frequency of clinical elevations (scores above the 2nd percentile) to the normative expectation.

Significance values were corrected for multiple comparisons (BASC-2 adj p = .004; CBCL adj p = .006).

Figure 1.

Percent of adolescents with adaptive functioning below age expectations

There was no significant relationship between age and raw scores on the CBCL or BASC-2, suggesting that reported behavior problems did not vary with age. Functional Communication was significantly and modestly related to performance on the PPVT-IV, such that higher PPVT-IV standard scores are associated with increased functional communication skills (r2 = .29, p < .002).

A trend toward significance was seen on the CBCL Attention Problems Scale, such that females were rated as having significantly higher levels of attention problems as compared to males with a moderate effect size (M Female = 62.68, M Male = 58.33, F (50) = −6.51, p = .014, d = 0.68). When correlations were examined by gender, a trend toward a significant positive relationship between age and CBCL Withdrawn/Depressed scores was identified for male participants only (τ = .33, p = .04, uncorrected). Results of a Fisher's Z test revealed that difference between the magnitudes of correlations was not significant, suggesting that caregiver ratings on this scale do not differ by gender. There was no significant effect of gender on adaptive functioning. There were no other significant differences by gender on measures of behavior or adaptive functioning.

Behavior and adaptive function

Overall, both internalizing and externalizing symptoms were inversely related to adaptive skills (Table 3). Notably, problems with attention were related to lower adaptive functioning across all measured subdomains. Please see Table 4 for detailed results of each regression analyses. In summary, BASC-2 Functional Communication was significantly predicted by PPVT-IV Standard Score, BASC-2 Atypicality, and BASC-2 Withdrawal (F (3, 48) = 23.18, p < .001), with the three predictors accounting for 54% of the variability. BASC-2 Attention Problems and Conduct Problems significantly accounted for 33% of the variance in caregiver reported skills related to BASC-2 Adaptability (F (2, 49) = 15.82, p < .001). BASC-2 Attention Problems and Withdrawal significantly accounted for 22% of the variance in BASC-2 Leadership (F (2, 49) = 16.84, p < .001) and 18% of the variance in BASC-2 Social Skills (F (2, 49) = 8.55, p = .001). Finally, BASC-2 Attention Problems accounted for 26% of the variance in BASC-2 ADLs (F (1, 50) = 21.24, p < .001).

Table 3.

Pearson correlations between BASC-2 Clinical and Adaptive Scales

| Clinical Scales | Adaptability | Social Skills | Leadership | Activities of Daily Living | Functional Communication | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Externalizing | Attention Problems | −0.55*** | −0.38** | −0.55*** | −0.52*** | −0.52*** |

| Hyperactivity | −0.34** | 0.03 | −0.18 | −0.31 | −0.18 | |

| Aggression | −0.41* | −0.15 | −0.18 | −0.21 | 0.04 | |

| Conduct Problems | −0.48*** | 0.06 | −0.08 | −0.19 | 0.00 | |

| Internalizing | Anxiety | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| Depression | −0.24 | −0.16 | −0.27 | −0.25 | −0.13 | |

| Somatization | −0.25 | −0.18 | −0.11 | −0.30* | 0.00 | |

| Atypicality | −0.32** | −0.18 | −0.35 | −0.37** | −0.53*** | |

| Withdrawal | −0.15 | −0.43*** | −0.45*** | −0.43 | −0.43*** |

N = 52.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤..01.

p ≤ .002 (corrected threshold for multiple comparisons)

Table 4.

Multiple Regression Models

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Communication | B | SE β | β | B | SE β | β | B | SE β | β |

| PPVT-IV Standard Score | 0.29 | 0.06 | 0.54 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.47 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.48 |

| Atypicality | −0.40 | 0.09 | −0.46 | −0.32 | 0.08 | −0.37 | |||

| Withdrawal | −0.27 | 0.08 | −0.32 | ||||||

| Adj R 2 | 0.28 | 0.48 | 0.57 | ||||||

| Adaptability | |||||||||

| Attention Problems | −0.70 | 0.15 | −0.55 | −0.54 | 0.15 | −0.43 | |||

| Conduct Problems | −0.32 | 0.12 | −0.33 | ||||||

| Adj R 2 | 0.29 | 0.37 | |||||||

| Leadership | |||||||||

| Attention Problems | −0.67 | 0.14 | −0.55 | −0.57 | 0.14 | −0.47 | |||

| Withdrawal | −0.23 | 0.08 | −0.33 | ||||||

| Adj R 2 | 0.30 | 0.41 | |||||||

| Social Skills | |||||||||

| Attention Problems | −0.34 | 0.10 | −0.43 | −0.28 | 0.10 | −0.35 | |||

| Withdrawal | −0.39 | 0.17 | −0.30 | ||||||

| Adj R 2 | 0.17 | 0.23 | |||||||

| Activities of Daily Living | |||||||||

| Attention Problems | −0.64 | 0.14 | −0.55 | ||||||

| Adj R 2 | 0.30 | ||||||||

N=52. All analyses conducted using stepwise multiple regression, with p of F-to-enter = .05 and p of F-to-remove = .10.

Clinical Utility of BASC-2

Comparisons between the percentage of individuals classified as at risk for behavior problems on the BASC-2 and CBCL scores suggest that both instruments identified greater than expected numbers of participants at risk for behavior problems (Table 5). On the BASC-2, a significantly higher proportion of adolescents with Down syndrome were identified as at risk for elevations on the Atypicality, Withdrawal, Attention Problems, and Hyperactivity Clinical Scales. Participants were identified as at significantly higher risk for problems across all CBCL Syndrome Scales when compared with normative expectations. In general, correlations between similarly named scales on the BASC-2 and CBCL were nonsignificant and of lower magnitude than those derived from the normative sample (Table 6). Intra-instrument correlations are derived from a subset of the normative sample for the BASC-2, which primarily included children and adolescents from regular school settings (Reynolds and Kemphaus, 2004).

Table 5.

Percentage of elevated scores on the BASC-II and CBCL Scales for individuals with Down syndrome

| At risk (%) | At risk (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBCL Composite Scales | BASC-2 Composite Scales | ||||

| Externalizing Problems** | 20 | Externalizing Problems | 16 | 70 | 94 |

| Internalizing Problems* | 14 | Internalizing Problems** | 4 | 15 | 95 |

| Total Problems** | 26 | Behavior Symptoms Index** | 22 | 69 | 85 |

| CBCL Syndrome Scales | BASC-2 Clinical Scales | ||||

| Aggressive Behavior** | 12 | Aggression | 6 | 50 | 100 |

| Rule-Breaking Behavior* | 5 | Conduct Problems | 12 | 80 | 83 |

| Anxious/Depressed* | 5 | Anxiety | 4 | 80 | 100 |

| Withdrawn/Depressed** | 12 | Depression | 4 | 100 | 98 |

| Somatic Complaints** | 10 | Somatization | 4 | 10 | 93 |

| Thought Problems** | 25 | Atypicality** | 25 | 64 | 67 |

| Social Problems** | 21 | Withdrawal** | 25 | 57 | 58 |

| Attention Problems** | 15 | Attention Problems** | 25 | 63 | 58 |

| Hyperactivity** | 26 | ||||

N = 52. Participants were classified as At Risk if scores were ≥ 1 SD (84th percentile) above the mean.

Percent of at risk elevations differed from normative expectations at p ≤ .05

p ≤ .005; Sensitivity and specificity were calculated using the CBCL as a gold -standard.

Table 6.

Correlations BASC-2 and CBCL Scales for adolescents with Down syndrome and normative sample

| Down syndrome r | Normative data a r | Fisher's Z | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBCL Composite Scales (SS) | BASC-2 Compos ite Scales (SS) | |||||

| Internalizing | Internalizing | 0.55 | 0.67 | −1.01 | 0.31 | |

| Internalizing | Externalizing | 0.05 | 0.53 | −2.85 | 0.00 | ** |

| Internalizing | Adaptive | −0.12 | −0.52 | 2.40 | 0.02 | * |

| Externalizing | Internalizing | 0.26 | 0.55 | −1.71 | 0.09 | |

| Externalizing | Adaptive | −0.10 | −0.61 | 3.21 | 0.00 | ** |

| BASC-2 Clinical Scales (raw) | CBCL Syndrome Scales (raw) | |||||

| Anxiety | Anxious Depressed | 0.08 | 0.48 | −2.33 | 0.02 | * |

| Depression | Anxious Depressed | 0.02 | 0.58 | −3.38 | 0.00 | ** |

| Depression | Withdrawn Depressed | 0.01 | 0.54 | −3.13 | 0.00 | ** |

| Somatization | Somatic Complaints | 0.24 | 0.54 | −1.89 | 0.06 | |

| Withdrawal | Withdrawn/Depressed | 0.05 | 0.65 | −3.82 | 0.00 | ** |

| Withdrawal | Social Problems | −0.03 | 0.59 | −3.73 | 0.00 | ** |

| Aggression | Aggressive Behavior | 0.01 | 0.77 | −5.32 | 0.00 | ** |

| Atypicality | Thought Problems | 0.20 | 0.59 | −2.50 | 0.01 | * |

| Attention Problems | Attention Problems | 0.00 | 0.65 | −4.08 | 0.00 | ** |

N = 52.

p < .05; p <. 002, corrected threshold for multiple comparisons.

Normative data is from the BASC-2 manual (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to explore the relationship between behavior problems and adaptive functioning in adolescents with Down syndrome using multiple caregiver report measures. Recruitment was balanced between community and clinic referrals, thus lending support to the generalizability of findings. Results confirm our hypothesis by demonstrating that adolescents with Down syndrome demonstrate clinically significant behavior problems with a higher frequency than age matched peers. Further, adolescents with Down syndrome demonstrate elevated frequencies of at-risk scores on both the CBCL and BASC −2. Regression analyses suggest that problems with attention and social withdrawal account for a substantial amount of variability in adaptive skills. Findings additionally provide information about the clinical utility of the BASC-2 as a measure of behavior and adaptive skills in adolescents with Down syndrome.

Previous studies of children with Down syndrome have found age to be associated with both externalizing and internalizing behavior symptoms (Dykens, et al., 2002; van Gameren-Oosterom, et al., 2013). Our findings do not support this pattern of behavior change during adolescence. It is possible that this changing behavior pattern may be occurring prior to adolescence, given that a decrease in externalizing behavior was documented in a sample that included children below the age of twelve.

Unsurprisingly, the majority of participants demonstrated adaptive skill deficits in at least one domain; however, not all measured domains were impacted equally. Ninety percent of our sample was rated as having deficits in functional communication skills. This finding is consistent with studies demonstrating that individuals with Down syndrome often demonstrate disproportionately impaired verbal skills (Silverman, 2007). In contrast, only 44% were rated as having difficulties with adaptability, suggesting that over half of the adolescents in our sample were viewed as flexible and responsive to changes in plans or routine.

Behavior problems have previously been related to adverse vocational, educational, and quality of life outcomes for individuals with Down syndrome and their families (Foley, et al., 2013). Our results confirm and extend these results by specifying the relationship between behavior problems and adaptive skills. Notably, a substantial amount of variability in adaptive skills was explained by relatively few problem behaviors. Attention problems and social withdrawal were most consistently identified as predictors. Further, there was no relationship between mood problems (e.g., anxiety or depression scales) and adaptive skill deficits. This is an important finding, given that research in adults with Down syndrome and in the broader population of adults with intellectual disability has generally focused on the association between affective problems and functional abilities (e.g. Esbensen & Benson, 2006, Walker, Dosen, Buitelaar, & Janzing, 2011; Thorpe, Pahwa, Bennett, Kirk, & Nanson, 2012).

Between 16 and 25 percent of adolescents in our sample were rated as having clinically elevated levels of attention problems; however, only one participant was treated for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Although we did not directly assess for ADHD in our study, our data lend support to studies that have found elevated incidence of ADHD diagnoses in children with Down syndrome (Ekstein, Glick, Weill et al., 2011). Clinicians are encouraged to routinely assess the functional impact of symptoms including inattentiveness, distractibility, and impulsivity, in patients with Down syndrome. This is particularly important given findings from studies that suggest computerized working memory interventions are feasible and efficacious in children with Down syndrome (Bennett, Holmes, & Buckley, 2013). Education plans should also include environmental supports to enhance attention, particularly in inclusion settings (e.g., preferential seating, cuing from an aide or teacher). More research is needed to determine the efficacy of medical and behavioral treatments in this population.

Medication intervention may also be considered on an individual basis. Results of a randomized double-blinded clinical trial found optimal dosing of methylphenidate to be effective in mediating symptoms of hyperkinetic disorder in 40% of children with intellectual disability (Simonoff, Taylor, Baird, & Bernard, 2013). Adverse effects were found to be similar to those identified in the typically developing population, although the authors recommended close monitoring given the elevated incidence of complicating medical problems. Results from these studies are encouraging, although additional studies are needed to document the safety, feasibility, and efficacy of medication and behavioral interventions in children with Down syndrome.

Interventions focused on enhancing social participation may have a positive effect on adaptive functioning. Children should be provided with opportunities for social activities with a variety of peers. Individualized educational plans should include opportunities to participate in both inclusion and self-contained programs, in order to facilitate social interaction. Curricular modifications should emphasize the development of functional communication skills, including learning personal information and locating data using available resources (e.g., internet, phone book). Our data also reinforce the importance of frequent opportunities for social interaction that are maintained throughout adolescence.

Data regarding the clinical utility of the BASC-2 in adolescents with Down syndrome are mixed. The composite scales from the BASC-2 appear to be less sensitive to internalizing problems and more sensitive to externalizing problems as compared with the CBCL; however, sensitivity is much improved at the level of the clinical sales. Convergent validity between the BASC-2 and CBCL was remarkably poor when compared to normative expectations. Clinicians are encouraged to consider the psychometric properties of rating instruments when collecting information regarding behavior in children with intellectual disability. Item specific analyses may provide additional clinical utility.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. It is possible that our findings did not reveal changes in behavior due to the restricted age range. Nevertheless, our results add to previous findings by suggesting that changed in behavior associated with age may occur gradually, and are perhaps most noticeable during childhood and adulthood. A second limitation is that our study measured adaptive function and behavior concurrently. It is likely that there is a bidirectional relationship between these constructs. Future studies should investigate these constructs in the context of a longitudinal study, in order to better understand this relationship. Finally, the use of stepwise regression was necessary due to our sample size; however, we acknowledge that this method may yield findings that are difficult to replicate.

Despite these limitations, our findings contribute to the understanding of the impact of behavior problems on adaptive functioning in individuals with Down syndrome. The substantial amount of variability in adaptive function that is accounted for by parent reported behavior problems suggests that specific areas of adaptive function may be useful outcome markers in studies designed to evaluate behavioral or pharmaceutical interventions. Our findings additionally highlight the predominant role of externalizing symptoms on adaptive functioning. Adolescents with Down syndrome should continue to participate in speech language therapy and social skills groups in order to promote functional communication skills and increase opportunities for social interaction. It is also important that adolescents are encouraged to become self-advocates who are encouraged to explicitly communicate when they are having difficulty understanding language or following conversations. Interventions designed to mediate inattention and social withdrawal are needed in order to promote independent functioning during adulthood in this population. Clinicians are encouraged to provide families with psychoeducation regarding the impact of attention problems on functioning in adolescents with Down syndrome and to consider the role of medical and behavioral interventions on the management of symptoms.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported with funds provided by the Jane and Richard Thomas Center for Down Syndrome at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, and the Seeman-Frakes and Graduate School Governance Student Awards from the University of Cincinnati.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist for ages 4-18. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 6 - 18. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Roscorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms and Profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; Burlington, VT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Beck FW, Black FL. Comparison of PPVT-R and WISC-R in a mild/moderate handicapped sample. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1986;62(3):891–894. doi: 10.2466/pms.1986.62.3.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell NL, Lassiter KS, Matthews TD, Hutchinson MB. Comparison of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test - Third Edition and Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Third Edition with university students. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001;57(3):417–22. doi: 10.1002/jclp.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender AH, Auciello D, Morrison CE, MacAllister WS, Zaroff CM. Comparing the convergent validity and clinical utility of the Behavior Assessment System for Children-Parent Rating Scales and Child Behavior Checklist in children with epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2008;13(1):237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett SJ, Holmes J, Buckley S. Computerized memory training leads to sustained improvement in visuospatial short-term memory skills in children with Down syndrome. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2013;118(3):179–192. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-118.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borthwick-Duffy SA, Lane KL, Widaman KF. Measuring problem behaviors in children with mental retardation: dimensions and predictors. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 1997;18(6):415–433. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(97)00020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JM, Bell SK, Keith LK. Concurrent validity of the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – Third Edition as an intelligence and achievement screener for low SES African American children. Asses sment. 2001;81(1):85–94. doi: 10.1177/107319110100800108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone G, Goyal P, Ares W, Lannigan E. Neurobehavioral disorders in children, adolescents, and young adults with Down syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2006;142C(3):158–172. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellino SM, Tooze JA, Flowers L, Parsons SK. The Peabody picture vocabulary test as a pre-screening tool for global cognitive functioning in brain tumor survivors. Journal of Neurooncology. 2011;104(2):559–63. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0521-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childers JS, Durham TW, Wilson S. Relation of performance on the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test with the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – Revised among preschool children. Perceptual Motor Skills. 1994;79(3):1195–9. doi: 10.2466/pms.1994.79.3.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collacott RA, Cooper SA, McGrother C. Differential rates of psychiatric disorders in adults with Down's syndrome compared with other mentally handicapped adults. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science. 1992;161:671–674. doi: 10.1192/bjp.161.5.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ruiter KP, Dekker MC, Verhulst FC, Koot HM. Developmental course of psychopathology in youths with and without intellectual disabilities. Journal of Child Psychology, Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2007;48(5):498–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker MC, Nunn R, Einfeld SE, Tonge BJ, Koot HM. Assessing emotional and behavioral problems in children with intellectual disability: revisiting the factor structure of the developmental behavior checklist. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2002;32(6):601–610. doi: 10.1023/a:1021263216093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle A, Ostrander R, Skare S, Crosby RD, August GJ. Convergent and criterion-related validity of the Behavior Assessment System for Children-Parent Rating Scale. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26(3):276–284. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2603_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn MD, Dunn LM. Pearson Picture Vocabulary Test. 4th Edition (PPVT-IV) Pearson; San Antonio, TX: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dykens EM, Kasari C. Maladaptive behavior in children with Prader-Willi syndrome, Down syndrome, and nonspecific mental retardation. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 1997;102(3):228–237. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(1997)102<0228:MBICWP>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens EM. Psychopathology in children with intellectual disability. Journal of Child Psychology Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2000;41(4):407–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens EM, Shah B, Sagun J, Beck T, King BH. Maladaptive behaviour in children and adolescents with Down's syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2002;46(6):484–492. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2002.00431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens EM, Hodapp RM, Evans DW. Profiles and development of adaptive behavior in children with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome, Research and Practice. 2006;9(3):45–50. doi: 10.3104/reprints.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esbensen AJ, Benson BA. A prospective analysis of life events, problem behaviours and depression in adults with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2006;50(4):248–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstein S, Glick B, Weill BK, Berger I. Down syndrome and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Journal of Child Neurology. 2011;26(10):1290–1295. doi: 10.1177/0883073811405201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley KR, Jacoby P, Girdler S, Bourke J, Pikora T, Lennox N, et al. Functioning and post-school transition outcomes for young people with Down syndrome. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2013;39(6):789–800. doi: 10.1111/cch.12019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gath A, Gumley D. Behaviour problems in retarded children with special reference to Down's syndrome. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;149:156–161. doi: 10.1192/bjp.149.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins BA, Eklund SJ, James DR, Foose AK. Adaptive behavior and cognitive function of adults with Down syndrome: modeling change with age. Mental Retardation. 2003;41(1):7–28. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2003)041<0007:ABACFO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland AJ, Hon J, Huppert FA, Stevens F. Incidence and course of dementia in people with Down's syndrome: findings from a population-based study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2000;44(2):138–146. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2000.00263.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland AJ, Hon J, Huppert FA, Stevens F, Watson P. Population-based study of the prevalence and presentation of dementia in adults with Down's syndrome. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;172:493–498. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.6.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes CS, Respess D, Greer T, Frentz J. Behavior problems in children with diabetes: disentangling possible scoring confounds on the Child Behavior Checklist. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1998;23(3):179–85. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/23.3.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrold C, Baddeley AD, Hewes AK. Verbal short-term memory deficits in Down syndrome: a consequence of problems in rehearsal? Journal of Child Psychology. Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2000;41(2):233–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS, Salzberg AD, Richters JE, Watanabe HK. Scales, diagnoses, and child psychopathology: I. CBCL and DISC relationships. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32(2):397–406. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199303000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahone ME, Martin R, Kates WR, Hay T, Horska A. Neuroimaging correlates of parent ratings of working memory in typically developing children. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2009;15(1):31–41. doi: 10.1017/S1355617708090164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston GM, Perry DW, Roy A. Manifestations of depression in people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 1997;41(6):476–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1997.tb00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers BA, Pueschel SM. Psychiatric disorders in persons with Down syndrome. Journal Nervous Mental Disorders. 1991;179(10):609–613. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199110000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicham R, Weitzdorfer R, Hauser E, Schubert M, Wurst E, Lubec G, Seidi R. Spectrum of cognitive, behavioural and emotional problems in children and young adults with Down syndrome. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2003;(supplementum (67)):173–191. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6721-2_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papazoglou A, Jacobson LA, Zabel TA. More than intelligence: distinct cognitive/behavioral clusters linked to adaptive dysfunction in children. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2013;19(2):189–97. doi: 10.1017/S1355617712001191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papazoglou A, Jacobson LA, Zabel TA. Sensitivity of the BASC-2 Adaptive Skills Composite in detecting adaptive impairment in a clinically referred sample of children and adolescents. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 2013;27(3):386–95. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2012.760651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SE, Mai CT, Canfield MA, Rickard R, Wang Y, Meyer RE, et al. Updated National Birth Prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the United States, 2004-2006. Birth Defects Research, Part A, Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 2010;88(12):1008–1016. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S. Psychopathology and mental retardation: survey of a developmental disabilities mental health program. Mental Retardation. 1982;20(3):128–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S, Levitan GW, McNally RJ. Emotionally disturbed mentally retarded people: an underserved population. The American Psychologist. 1982;37(4):361–367. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.37.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss S, Levitan GW, Szyszko J. Emotional disturbance and mental retardation: diagnostic overshadowing. American Journal of Mental Deficiency. 1982;86(6):567–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. Behavioral Assessment System for Children. 2nd Edition Pearson; San Antonio, TX: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rush KS, Bowman LG, Eidman SL, Toole LM, Mortenson BP. Assessing psychopathology in individuals with developmental disabilities - review. Behavior Modification. 2004;28(5):621–637. doi: 10.1177/0145445503259830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Floyd FJ, Greenberg JS, Hong J, Taylor JL, Doescher H. Factors predictive of midlife occupational attainment and psychological functioning in adults with mild intellectual deficits. American Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability. 2009;114(2):128–143. doi: 10.1352/2009.114.128-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman W. Down syndrome: Cognitive phenotype. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Review. 2007;13(3):228–236. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonoff E, Taylor E, Baird G, Bernard S, Chadwick O, Liang H, et al. Randomized controlled double-blind trial of optimal dose methylphenidate in children and adolescents with severe attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and intellectual disability. Journal of Child Psychology, Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2013;54(5):527–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe L, Pahwa P, Bennett B, Kirk A, Nanson J. Clinical Predictors of Mortality in Adults with Intellectual Disabilities with and without Down Syndrome. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research. 2012:943890. doi: 10.1155/2012/943890. 2012(2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gameren-Oosterom HB, Fekkes M, Buitendijk SE, Mohangoo AD, Bruil J, Van Wouwe JP. Development, problem behaviour, and quality of life in a population based sample of eight-year-old children with Down syndrome. PLos One. 2011;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gameren-Oosterom HB, Fekkes M, van Wouwe JP, Detmar SB, Oudesluys-Murphy AM, Verkerk PH. Problem Behavior of Individuals with Down Syndrome in a Nationwide Cohort Assessed in Late Adolescence. Journal of Pediatrics. 2013;163(5):1396–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JC, Dosen A, Buitelaar JK, Janzing JG. Depression in Down syndrome: A review of the literature. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2011;32(5):1432–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren AC, Holroyd S, Folstein MF. Major depression in Down's syndrome. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;155:202–205. doi: 10.1192/bjp.155.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]